Self-Consistent Calculation on the Time-Dependent Electrons Transport Properties of a Quantum Wire

Abstract

Responses of a quantum wire (QW) connected with wide reservoirs to time-dependent external voltages are investigated in self-consistent manner. Distributions of the internal potential and the induced charge density, capacitance, and conductance are calculated. Results indicate that these physical quantities depend strongly on the Fermi energy of systems and the frequency of external voltages. With the increase of the Fermi energy, capacitance and conductance show some resonant peaks due to the open of the next higher quantum channels and the oscillations related to the longitudinal resonant electron states. Frequency-dependent conductance shows two different responses to the external voltages, inductive-like and capacitive-like; and the peaks structure of capacitance is related to the plasmon-like excitation in mesoscopic conductor.

1. Introduction

With the development of nanotechnology, it is possible to define constrictions with geometrical dimension which is smaller than the elastic, inelastic mean free paths and with various forms, for example, quantum wires (QWs). Therefore, electrons transport in these constriction structures has attracted great research interest in recent years, both experimentally and theoretically, because of its fundamental importance and potential microelectronic applications [1–6]. Studies of the responses of the QWs to external voltages have been frequently reported in the literatures. An important issue is the effect of the Coulomb interaction between electrons on the conductance of the QWs. For a time-dependent case, the interaction plays a key role in ensuring the charge conservation and the gauge invariance under a potential shift [1–3]. Gasparian et al. had used the linear response theory (LRT) and the scattering matrix theory (SMT) to develop a theoretical formalism to analyze the responses of mesoscopic conductors to external disturbance [7]. This is an important advance in the theory of mesoscopic physics: the first step in this theory is to consider the system responses to external perturbation; the second step is to consider the internal potential formed by the interaction. The effect of the interaction on the ac conductance of a QW with reservoirs was studied in [8] by using the random phase approximation (RPA). Based on the Hartree-Fock approximation (HFA), the distributions of the internal potential and electron density in the system were investigated [9]. Also, Sablikov and Shchamkhalova studied the time-dependent electron transport in the QW with Coulomb interaction and gave the distributions of the internal potential and electron density [10]. Furthermore, the ac response in QWs with infinite length had been discussed [11]. Hence, the responses to the external voltages, for instance, the ac conductance, the distributions of the internal potential, and electron density in the QWs, have been investigated. But the interacting current response and internal potential were determined by some experiential approaches [2] or by Thomas-Fermi approximation (TFA) in the low-frequency limit [12]. However, the mesoscopic devices in future all work on the higher frequencies conditions; so some detailed knowledge of the time-dependent transport properties of mesoscopic structures are required. In our previous work [13], we have developed a general self-consistent electrons dynamic transport theory for multiprobe mesoscopic conductor, in which e-e interaction is fully considered. In our theory, since the local current response, the charge induced by external voltages, and the Lindhard function are generally formulated, in principle, the internal potential and interacting conductance of any systems can be calculated by self-consistent manner. In this paper, we will briefly review the self-consistent theory and calculate the internal characteristic potential and the induced charge density in a QW including the transition regions and present the numerical verification of the mesoscopic capacitance and conductance.

2. Theory and Model

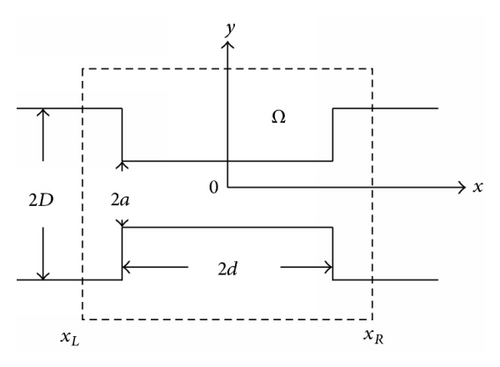

Below we consider a model that includes a narrow ballistic QW with width 2a, that is, QC (C: |x| ≤ d and |y| ≤ 2a), and two large electrons reservoirs with width 2D, that is, the left (L: x < −d and |y| ≤ 2D) and right (R: x > d and |y| ≤ 2D) reservoirs, as shown in Figure 1. The dashed line box labeled by Ω in Figure 1 includes the whole QW and parts of the reservoirs, and it is large enough to cover all the regions with varying distributions of potential and charge. This means that all the electric-field lines come from and end at the charge inside Ω.

The unknown coefficients in the above wave functions can be determined by using the boundary conditions of the wave functions. In general, is now matched to at x = ±d with the requirement that amplitudes and derivatives with respect to x are equal; then the scattering states wave functions of electrons in transition region may be eliminated.

2.1. Internal Characteristic Potential and Charge Density

2.2. Mesoscopic Capacitance and Conductance

3. Results and Discussions

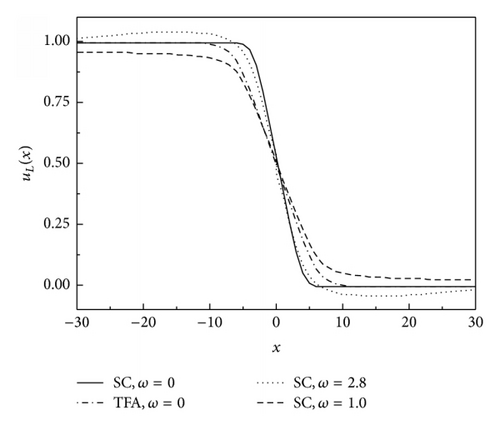

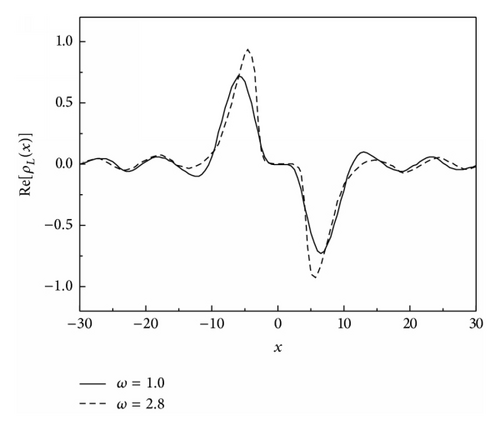

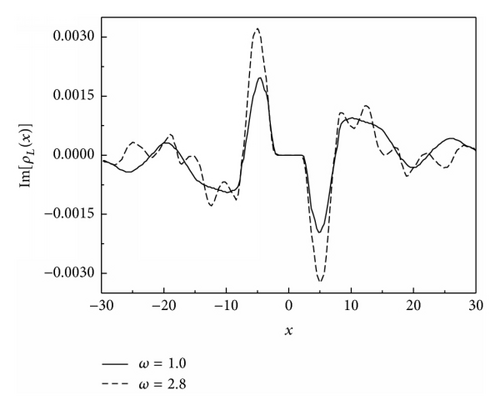

In Figures 2–4 we present the distributions of the internal characteristic potential function uL(x) and charge density ρL(x) for two values of external frequency ω = 1,2.8 by setting the Fermi energy EF = 0.8, which is smaller than transverse ground energy of the QW. In this case, the transverse ground energy plays a key role of a potential barrier for the incident electrons, so the electrons show the behavior of single barrier tunneling; it is equivalent to a barrier capacitor. From the profiles of uL(x), one can find that uL(x) is a smooth curve and almost linear inside the transition region of the QW. Also, the potential drop is uniform between the two ends of the shielding area Ω. Under the zero frequency, in comparison with the results given by the self-consistent manner (SC) with results of the Thomas-Fermi approximation (TFA), one can find that in this case our results agree well with that of the TFA, but, with the increase of the frequency, uL(x) shows some notable differences between them and the potential drop occurs not only in the two ends of reservoirs but also in the reservoirs.

The induced charge is considerable only around the left and right ends of the QW, and some small oscillation can be observed, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. Moreover, the charge otherwise is almost zero, but the variation of the characteristic potential does not vanish; this is because the one-dimensional charge distribution is given by integrating over the cross-sectional area of the system, and the cross-sectional area of reservoir is much larger than that of the QW. Importantly, in comparison with results given by preceding researches, uL(x) and ρL(x) are complex with extremely small imaginary part (here, the imaginary part of uL(x) is too small, so it isn’t presented in Figure 2) and the imaginary part of them should not be ignored because it gives rise to a real admittance, which actually corresponds to the charge-relaxation resistance.

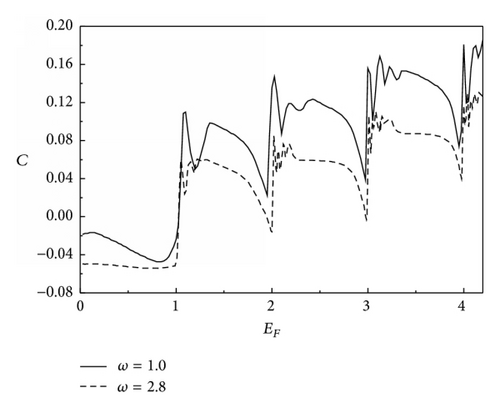

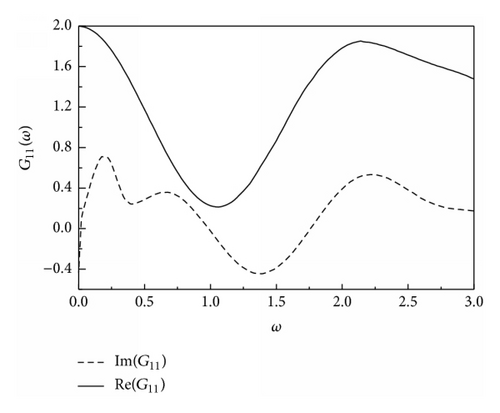

At zero temperature, the diagonal matrix elements of conductance G11 in Figure 5 show some positive and negative resonant peaks around the integral values of Δ with the increase of the Fermi energy; this corresponds to the step jump of the dc conductance of the QW, which is caused by the opening of additional quantum channels in the QW. This is a resonance related to the transverse energy levels of the QW. Moreover, there are other types of resonance related to the longitudinal motion of electrons in the QW. G11 and C (in Figure 6) show step-like and oscillatory behaviors between the two neighboring resonances, which corresponds to the opening of the next higher channel. Also the strength and frequency of oscillation increase with the frequency of the external field increasing. This oscillation may be caused by longitudinal resonant electron states that occur when the length of the QW is approximately equal to integer multiples of half longitudinal Fermi wavelength [15].

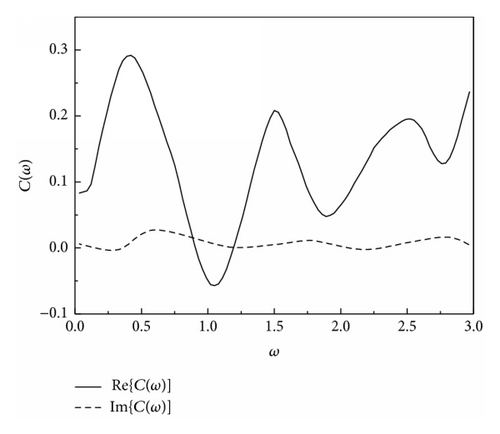

Figures 7 and 8 show G11(ω) and C(ω) as functions of the frequency of external voltages by setting EF = 2.4, respectively, which is two times more than the ground energy. Towards this case, electrons through the second channel, the real part of G11(ω) begins to decrease from two times conductance unit, and the real and imaginary parts G11(ω) show irregular oscillatory behaviors. These indicate e-e interaction leads to the nonuniform distribution of current in transport system. Moreover, another important property is current phase. It should be pointed that the conductance is complex, in which the imaginary part refers to the phase difference between the current and voltage; this means that there are two different responses to the external voltage, inductive-like and capacitive-like, which depend on the plus sign and minus sign of the conductance matrix elements, respectively. As is well known, the plasmon excitations exist for interacting electron gas of bulk. It is significant to ask whether there is some quasiparticle excitation related to the collective motion of the electrons in the mesoscopic conductor. Reference [16] had indicated that there existed some excitations, such as plasmons, in mesoscopic conductor, and they had effect on the ac transport properties. Here, some peaks structure in curve of the real part of C(ω) are observed; we believe that these peaks are related to the plasmon excitation in the mesoscopic conductor.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented the calculation of various physics quantities, such as the distributions of the internal potential and the induced charge density, the frequency-dependent capacitance, and conductance of the QW. The induced charge is mainly distributed in the transition regions between the reservoirs. For the results of capacitance and conductance versus Fermi energy, some resonant peaks due to the opening of the next higher quantum channels and the oscillations related to the longitudinal resonant electron states of the QW are observed. The frequency-dependent conductance shows two different responses to the external voltage, inductive-like and capacitive-like, which depend on the plus sign and minus sign of the conductance matrix elements. The peaks structure of frequency-dependent capacitance is related to the plasmon-like excitation in mesoscopic conductor.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 11304276, 11404283) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant nos. 2014A030307028, 2014A030307035).