MTHFR C677T Gene Polymorphism and Head and Neck Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis Based on 23 Publications

Abstract

Objective. Conflicting results on the association between MTHFR polymorphism and head and neck cancer (HNC) risk were reported. We therefore performed a meta-analysis to derive a more precise relationship between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk. Methods. Three online databases of PubMed, Embase, and CNKI were researched on the associations between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk. Twenty-three published case-control studies involving 4,955 cases and 8,805 controls were collected. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to evaluate the relationship between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk. Sensitivity analysis, cumulative analyses, and publication bias were conducted to validate the strength of the results. Results. Overall, no significant association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk was found in this meta-analysis (T versus C: OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.92–1.18; TT versus CC: OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.90–1.46; CT versus CC: OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.85–1.17; CT + TT versus CC: OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.87–1.18; TT versus CC + CT: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.98–1.26). In the subgroup analysis by HWE, ethnicity, study design, cancer location, and negative significant associations were detected in almost all genetic models, except for few significant risks that were found in thyroid cancer. Conclusion. This meta-analysis demonstrates that MTHFR C677T polymorphism may not be a risk factor for the developing of HNC.

1. Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide. It affects the upper aerodigestive epithelium of the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx [1]. In 2008, approximately 633,000 new cases and 355,000 deaths occurred because of HNC particularly in South-Central Asia and Central and Eastern Europe [2, 3]. Treatment options for HNC are complicated and include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and biological treatments that decrease the quality of life of patients with functional disabilities and facial abnormalities. HNC is a multifactorial disease that may be caused by various complex factors, including human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, lifestyle, and genetic factors [4].

Smoking and alcohol consumption are the major risk factors of HNC. Genetic mutations may potentially alter the susceptibility of an individual to HNC [5]. However, only a small proportion of vulnerable individuals may develop HNC. To date, genetic mutations such as single nucleotide polymorphisms are important for tumorigenesis and increase the risk of developing HNC and other cancers.

Folate is important in deoxynucleoside synthesis to provide methyl groups and in intracellular methylation reactions [6]. Low folate levels can result in uracil misincorporation during DNA synthesis, leading to chromosomal damage, breaks in DNA strands, impaired DNA repair, and DNA hypomethylation [7]. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) is an important enzyme in folate metabolism. Epidemiological evidence suggests that the genetic variants encoding the enzymes involved in folate metabolism may increase the risk of HNC by altering DNA methylation synthesis and genomic stability. Genetic mutations in MTHFR gene alter folate level and DNA methylation that may lead to hereditary diseases and cancer development [8–10].

MTHFR C677T (Ala222Val) polymorphism may result in cancer development by altering the activity of MTHFR enzyme [11]. In 2002, Weinstein et al. conducted the first study and reported a negative association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk [12]. Since then, numerous studies have been performed to determine the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk, but the results are conflicting. In 2009, Boccia et al. conducted a meta-analysis of nine published studies [13]. Additional studies on the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk have been published. Therefore, a comprehensive meta-analysis of all the relevant studies should be performed to predict this association accurately.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

Three online bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, and CNKI) were searched with the following search terms “head and neck cancer,” “oropharyngeal cancer,” “MTHFR,” “methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase,” “polymorphism,” “variant,” and “meta-analysis” in English and Chinese. Relevant studies were manually searched to identify from the references of original studies and review articles on the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk that were published from 2002 (when the first study on this topic was published) to August 10, 2014. All the selected studies complied with the following three inclusion criteria: (a) case-control study on the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk, (b) sufficient published data for estimating the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and (c) only the largest or most recent publication that was selected when multiple studies reported the same or overlapping data [14].

2.2. Data Extraction

Two investigators (Niu and Deng) independently extracted the following data from each included study: the first author’s name, publication date, country, ethnicity (categorized as Asian, Caucasian, and mixed race), study design, number of cases and controls subjects, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), minor allele frequency (MAF), and cancer location. The information from all included studies was compared in terms of accuracy, and discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer until consensus was achieved.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Crude ORs with 95% CIs were calculated to assess the strength of the correlation between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk. Pooled ORs were calculated for allele contrast model (T versus C), codominant model (TT versus CC, CT versus CC), dominant model (TT + CT versus CC), and recessive model (TT versus CC + CT), respectively. Subgroup analysis was performed to statistically analyze HWE, ethnicity, study design, and cancer location. Heterogeneity assumption was calculated based on the I2 statistics with low, moderate, and high I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively [15, 16]. OR estimation of each models was calculated by using the fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method) if the I2 ≤ 50% (which indicated a lack of heterogeneity) [17]. Otherwise, a random-effects model (the DerSimonian and Laird method) was used [18]. Potential publication bias was estimated by the Egger’s linear regression test [19]. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Two-sided P values were used, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

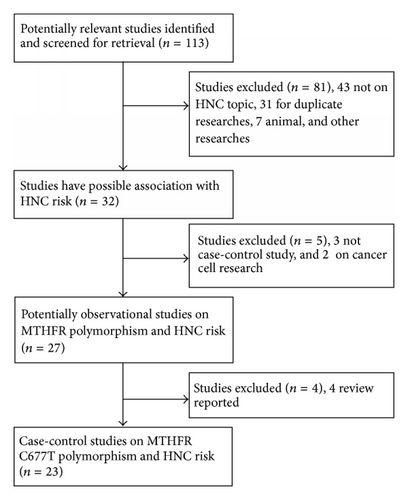

One hundred thirteen articles were retrieved by literature search. After a careful evaluation, twenty-three related case-control studies on the relationship between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk were included in this meta-analysis (Figure 1) [12, 20–41]. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of these studies. Of the 23 studies, 9 studies focused on Asian populations [20, 24, 28, 29, 31, 33, 37–39], 10 studies described Caucasian populations [21–23, 25, 27, 30, 32, 35, 40, 41], and 4 studies assessed mixed populations [12, 26, 34, 36]. The diverse genotyping methods included PCR-RFLP and TaqMan, and the genotypic distribution of the controls was consistent with the HWE in all except four studies [23, 25, 26, 39].

| Genotype distribution | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Year | Country/region | Racial descent | Source of controls | Case | Control | Case | Control | Genotyping type | P for HWE | MAF | Location | ||||

| CC | CT | TT | CC | CT | TT | |||||||||||

| Weinstein [12] | 2002 | Puerto Rico | Mixed | Population control | 135 | 146 | 67 | 53 | 15 | 69 | 62 | 15 | PCR-RFLP | 0.85 | 0.32 | Oral |

| Kureshi [20] | 2004 | Pakistan | Asian | NA | 50 | 54 | 32 | 18 | 0 | 32 | 18 | 4 | PCR-RFLP | 0.52 | 0.24 | HN |

| Neumann [21] | 2005 | USA | Caucasian | Hospital control | 537 | 545 | 258 | 244 | 35 | 278 | 216 | 51 | PCR-RFLP | 0.34 | 0.29 | HN |

| Capaccio [22] | 2005 | Italy | Caucasian | Population control | 65 | 100 | 18 | 33 | 14 | 36 | 46 | 18 | PCR-RFLP | 0.62 | 0.41 | HN |

| Vairaktaris [23] | 2006 | Greece | Caucasian | Population control | 110 | 120 | 28 | 76 | 6 | 45 | 65 | 10 | PCR-RFLP | 0.04 | 0.35 | Oral |

| Suzuki [24] | 2007 | Japan | Asian | Hospital control | 237 | 711 | 88 | 113 | 36 | 252 | 331 | 128 | TaqMan | 0.29 | 0.41 | HN |

| Reljic [25] | 2007 | Croatia | Caucasian | Population control | 81 | 102 | 45 | 27 | 9 | 35 | 59 | 8 | PCR-RFLP | 0.01 | 0.37 | HN |

| Hsiung [26] | 2007 | USA | Mixed | Population control | 277 | 524 | 128 | 149 | 218 | 306 | NA | NA | NA | HN | ||

| Hung [27] | 2007 | Europe | Caucasian | Hospital control | 779 | 2530 | 373 | 327 | 79 | 1272 | 1025 | 233 | TaqMan | 0.20 | 0.30 | HN |

| Solomon [28] | 2008 | India | Asian | NA | 126 | 100 | 48 | 55 | 23 | 48 | 42 | 10 | PCR-RFLP | 0.86 | 0.31 | Oral |

| Siraj [35] | 2008 | Saudi Arabia | Caucasian | Population control | 49 | 511 | 30 | 18 | 1 | 372 | 126 | 13 | PCR-RFLP | 0.55 | 0.15 | Thyroid |

| Ni [29] | 2008 | China | Asian | Hospital control | 207 | 400 | 48 | 95 | 64 | 152 | 187 | 61 | PCR-RFLP | 0.78 | 0.39 | Laryngeal |

| Rodrigues [36] | 2010 | Brazil | Mixed | Population control | 100 | 100 | 44 | 43 | 13 | 46 | 40 | 14 | PCR-RFLP | 0.28 | 0.34 | HN |

| Kruszyna [30] | 2010 | Poland | Caucasian | Population control | 131 | 250 | 69 | 52 | 10 | 126 | 104 | 20 | PCR-RFLP | 0.82 | 0.29 | Laryngeal |

| Cao [37] | 2010 | China | Asian | Population control | 511 | 552 | 310 | 169 | 32 | 334 | 188 | 30 | PCR-RFLP | 0.60 | 0.23 | NP |

| Tsai [31] | 2011 | Taiwan | Asian | Hospital control | 620 | 620 | 391 | 186 | 43 | 322 | 236 | 62 | PCR-RFLP | 0.06 | 0.29 | Oral |

| Supic [32] | 2011 | Serbia | Caucasian | Hospital control | 96 | 162 | 50 | 32 | 14 | 80 | 66 | 16 | PCR-RFLP | 0.66 | 0.30 | Oral |

| Sailasree [33] | 2011 | India | Asian | Hospital control | 101 | 138 | 92 | 8 | 1 | 108 | 29 | 1 | PCR-RFLP | 0.53 | 0.11 | Oral |

| Prasad [38] | 2011 | India | Asian | NA | 97 | 241 | 86 | 10 | 1 | 228 | 12 | 1 | PCR-RFLP | 0.07 | 0.03 | Thyroid |

| Fard-Esfahani [39] | 2011 | Iran | Asian | Hospital control | 154 | 198 | 69 | 71 | 14 | 82 | 108 | 8 | multiplex PCR | <0.01 | 0.31 | Thyroid |

| Ozdemir [40] | 2012 | Turkey | Caucasian | NA | 60 | 50 | 28 | 25 | 7 | 33 | 14 | 3 | Real-time PCR | 0.38 | 0.20 | Thyroid |

| Galbiatti [34] | 2012 | Brazil | Mixed | Population control | 322 | 531 | 130 | 147 | 45 | 226 | 250 | 55 | PCR-RFLP | 0.24 | 0.34 | HN |

| Vylliotis [41] | 2013 | Greek/Germany | Caucasian | Population control | 110 | 120 | 76 | 28 | 6 | 65 | 45 | 10 | PCR-RFLP | 0.58 | 0.27 | Oral |

- HWE in controls.

- MAF: minor allele frequency in controls.

- NA: not applicable.

- HN: head and neck.

- NP: nasopharyngeal.

3.2. Meta-Analysis

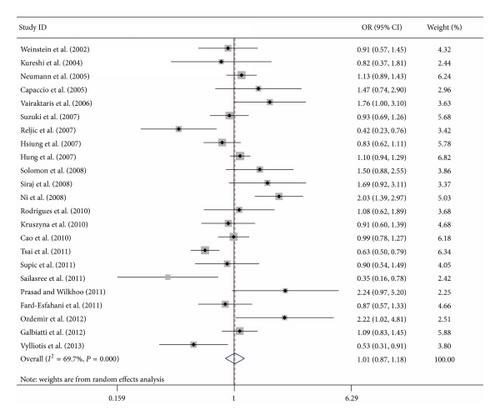

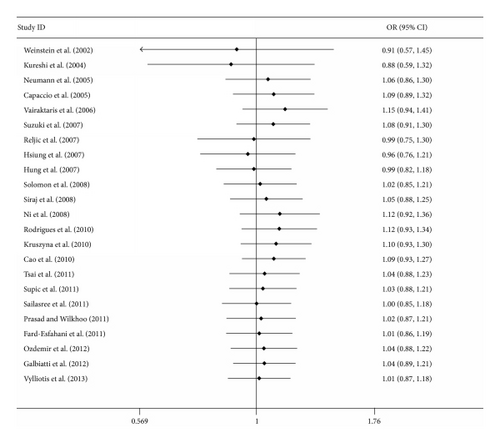

The main results of this meta-analysis and heterogeneity test are presented in Table 2. Overall, no significant association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk was found in this meta-analysis (T versus C: OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.92–1.18, P = 0.55, I2 = 72.5%; TT versus CC: OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.90–1.46, P = 0.26, I2 = 56.8%; CT versus CC: OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.85–1.17, P = 0.99, I2 = 65.8%; CT + TT versus CC: OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.87–1.18, P = 0.86, I2 = 69.7% (Figure 2); TT versus CC + CT: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.98–1.26, P = 0.10, I2 = 49.8%). Subsequent analysis of the HWE studies showed similar lack of associations between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk (T versus C: OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.92–1.21, P = 0.47, I2 = 75.0%; TT versus CC: OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.88–1.48, P = 0.34, I2 = 61.4%; CT versus CC: OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.88–1.19, P = 0.76, I2 = 60.3%; CT + TT versus CC: OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.88–1.20, P = 0.69, I2 = 68.4%; TT versus CC + CT: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.89–1.39, P = 0.35, I2 = 52.2%). Further, stratified analysis of ethnicity, study design, cancer location, and smoking habits showed no significant association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk. Notable, slight increased risks were found in the risk of developing thyroid cancer (T versus C: OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.03–1.65, P = 0.04, I2 = 43.9%; TT versus CC: OR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.04–4.10, P = 0.04, I2 = 0.0%).

| T versus C | TT versus CC | CT versus CC | CT + TT versus CC | TT versus CC + CT | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | I2 (%)a | OR | 95% CI | P | I2 (%)a | OR | 95% CI | P | I2 (%)a | OR | 95% CI | P | I2 (%)a | OR | 95% CI | P | I2 (%) | |

| Total | 1.04 | 0.92–1.18 | 0.55 | 72.5 | 1.15 | 0.90–1.46 | 0.26 | 56.8 | 1.00 | 0.85–1.17 | 0.99 | 65.8 | 1.01 | 0.87–1.18 | 0.86 | 69.7 | 1.11 | 0.98–1.26 | 0.10 | 49.8 |

| HWE | 1.05 | 0.92–1.21 | 0.47 | 75.0 | 1.14 | 0.88–1.48 | 0.34 | 61.4 | 1.02 | 0.88–1.19 | 0.76 | 60.3 | 1.03 | 0.88–1.20 | 0.69 | 68.4 | 1.11 | 0.89–1.39 | 0.35 | 52.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Asian | 1.03 | 0.78–1.36 | 0.83 | 86.0 | 1.29 | 0.73–2.28 | 0.38 | 79.6 | 0.96 | 0.73–1.25 | 0.75 | 70.8 | 1.00 | 0.74–1.36 | 0.99 | 80.4 | 1.28 | 0.80–2.06 | 0.30 | 74.0 |

| Caucasian | 1.39 | 0.89–1.20 | 0.65 | 49.1 | 1.04 | 0.85–1.27 | 0.66 | 0.0 | 1.04 | 0.81–1.35 | 0.75 | 69.5 | 1.05 | 0.83–1.33 | 0.67 | 66.3 | 1.01 | 0.84–1.22 | 0.90 | 0.0 |

| Other | 1.08 | 0.92–1.27 | 0.36 | 0.0 | 1.25 | 0.87–1.78 | 0.23 | 0.0 | 1.00 | 0.79–1.27 | 0.98 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.15 | 0.68 | 0.0 | 1.24 | 0.89–1.74 | 0.21 | 0.0 |

| Design | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PB | 1.01 | 0.90–1.14 | 0.84 | 29.5 | 1.16 | 0.92–1.46 | 0.21 | 0.0 | 0.95 | 0.76–1.20 | 0.68 | 60.1 | 0.96 | 0.80–1.15 | 0.64 | 53.5 | 1.18 | 0.95–1.74 | 0.14 | 0.0 |

| HB | 0.98 | 0.77–1.25 | 0.86 | 87.9 | 1.09 | 0.69–1.74 | 0.71 | 82.9 | 0.94 | 0.72–1.22 | 0.72 | 79.1 | 0.96 | 0.72–1.27 | 0.76 | 84.3 | 1.07 | 0.72–1.58 | 0.74 | 79.2 |

| Location | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oral | 0.88 | 0.67–1.17 | 0.38 | 75.3 | 0.85 | 0.64–1.12 | 0.25 | 48.0 | 0.81 | 0.57–1.15 | 0.24 | 70.7 | 0.84 | 0.59–1.20 | 0.33 | 74.4 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.20 | 0.52 | 34.0 |

| Laryngeal | 1.33 | 0.68–2.60 | 0.40 | 90.6 | 1.82 | 0.51–6.44 | 0.353 | 86.1 | 1.22 | 0.70–2.13 | 0.48 | 70.5 | 1.37 | 0.63–3.00 | 0.43 | 86.8 | 1.64 | 0.64–4.17 | 0.30 | 77.9 |

| Thyroid | 1.30 | 1.03–1.65 | 0.04 | 43.9 | 2.06 | 1.04–4.10 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 1.48 | 0.84–2.62 | 0.17 | 65.9 | 1.53 | 0.92–2.53 | 0.10 | 60.5 | 2.02 | 1.04–3.92 | 0.04 | 0.0 |

- aTest for heterogeneity.

- PB: population based; HB: hospital based.

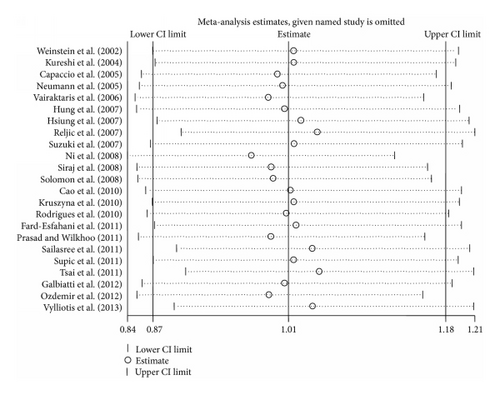

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis and Cumulative Analysis

Each study included in this meta-analysis was deleted one by one to determine the effect of an individual dataset to the pooled ORs; the results were consistent in all of the research genetic models (Figure 3 for the dominant model), indicating that our results are statistically robust (Table 3 for the dominant model). In the cumulative meta-analysis, the results always showed negative association with the increasing number of studies (Figure 4 for the dominant model).

| Study omitted | Estimate | 95% conf. interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weinstein et al. (2002) [12] | 1.0189941 | 0.87112659 | 1.1919612 |

| Kureshi et al. (2004) [20] | 1.0193014 | 0.87365657 | 1.1892264 |

| Capaccio et al. (2005) [22] | 1.0022544 | 0.85940462 | 1.1688484 |

| Neumann et al. (2005) [21] | 1.007629 | 0.85724384 | 1.184396 |

| Vairaktaris et al. (2006) [23] | 0.99266464 | 0.85276967 | 1.155509 |

| Hung et al. (2007) [27] | 1.0095826 | 0.85412776 | 1.193331 |

| Hsiung et al. (2007) [26] | 1.0266064 | 0.87583935 | 1.2033266 |

| Reljic et al. (2007) [25] | 1.0438555 | 0.90103817 | 1.2093099 |

| Suzuki et al. (2007) [24] | 1.0195761 | 0.86892009 | 1.1963534 |

| Ni et al. (2008) [29] | 0.97470093 | 0.84459507 | 1.1248491 |

| Siraj et al. (2008) [35] | 0.9954946 | 0.85466665 | 1.1595275 |

| Solomon et al. (2008) [28] | 0.99778956 | 0.85548556 | 1.1637648 |

| Cao et al. (2010) [37] | 1.0159856 | 0.86369467 | 1.1951293 |

| Kruszyna et al. (2010) [30] | 1.0192744 | 0.87083119 | 1.1930214 |

| Rodrigues et al. (2010) [36] | 1.0113139 | 0.86534274 | 1.1819084 |

| Fard-Esfahani et al. (2011) [39] | 1.0215796 | 0.87302911 | 1.1954068 |

| Prasad and Wilkhoo (2011) [38] | 0.99519187 | 0.85606372 | 1.1569312 |

| Sailasree et al. (2011) [33] | 1.0387301 | 0.89613956 | 1.2040093 |

| Supic et al. (2011) [32] | 1.0191994 | 0.87169868 | 1.1916586 |

| Tsai et al. (2011) [31] | 1.0461444 | 0.90586507 | 1.2081468 |

| Galbiatti et al. (2012) [34] | 1.0096141 | 0.85997182 | 1.1852955 |

| Ozdemir et al. (2012) [40] | 0.99327004 | 0.85463184 | 1.1543981 |

| Vylliotis et al. (2013) [41] | 1.0391399 | 0.89383554 | 1.2080653 |

| Combined | 1.0136127 | 0.87153344 | 1.178854 |

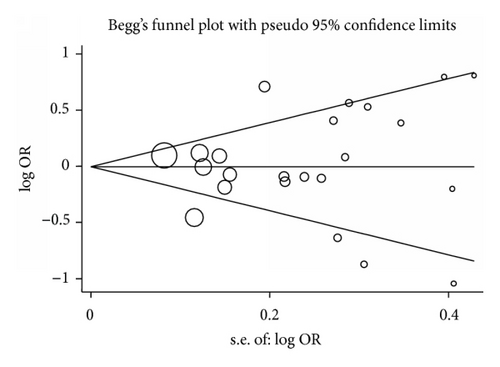

3.4. Publication Bias

Funnel plot and Egger’s test were performed to estimate the publication bias among the included studies. Shapes of the funnel plots for all genetic models did not reveal any asymmetrical evidence (Figure 5 showed the funnel plots for the dominant model in all populations). The result was further supported by the data with Egger’s test. No significant publication bias was found in this meta-analysis (P = 0.85 for T versus C; P = 0.86 for TT versus CC; P = 0.91 for CT versus CC; P = 0.72 for CT + TT versus CC; P = 0.97 for TT versus CC + CT).

4. Discussion

MTHFR irreversibly catalyzes the conversion of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which is a cosubstrate in the transmethylation of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine is the precursor of S-adenosyl-L-methionine, which is the primary methyl donor during DNA methylation process [42, 43]. In another metabolic reaction, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate is involved in the conversion of deoxyuridylate monophosphate to deoxythymidylate monophosphate. Low levels of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate would result in increasing the amounts of uracil incorporated in DNA to replace thymine, thereby increasing the ratio of point mutations and resulting in DNA breakage [6]. All of these factors are important in cancer development.

Molecular studies have shown that genetic susceptibility is one of the most important risk factors for cancer development. MTHFR gene is mapped in chromosome 1p36.3, is composed of 11 exons and 10 introns, and encodes a 77 KD protein [44, 45]. MTHFR gene C677T polymorphism, which is characterized by the transition of cytosine to thymine, leads to an amino acid change from alanine (Ala) to valine (Val) at codon 222 in exon 4. Previous studies have shown individuals with mutant homozygous 677TT genotype and heterozygous 677CT genotype showed approximately 30% and 65% activities of the MTHFR enzyme, respectively, compared with individuals with wild-type 677CC genotype [11]. Both heterozygous (CT) and homozygous (TT) variants possibly increase enzyme thermolability, reduce MTHFR enzyme activity, and decrease folate concentrations in plasma and red blood cells [46].

To date, large numbers of studies have investigated the association between the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and cancer risks, but the results are inconsistent. The MTHFR C677T variant is a possible risk factor of pancreatic [46], esophageal [47], and breast cancers [48] but exerts a possible protective effect against colorectal cancer [49]. However, the MTHFR C677T variant is not associated with lung [50] and prostate cancers [51].

In 2002, Weinstein et al. observe no association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC (oral cancer) risk in a Puerto Rican population. Since then, many studies have assessed this association but have obtained inconsistent results. Solomon et al. [28] found that the mutation in homozygous 677TT genotype is associated with a high risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma among Indian heavy drinkers (OR = 3.0; 95% CI = 2.02–4.0). Ni et al. [29] also found that the individuals with 677CT and 677TT genotype had a 1.66-fold (95% CI: 1.08–2.52) and 3.35-fold (95% CI: 2.07–5.54) increased risk of developing laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, respectively, compared with those who had 677CC genotype in a Chinese population. Vairaktaris et al. [23] supposed that mutations in MTHFR slightly increased the risk of oral cancers. Capaccio et al. [22] and Neumann et al. [21] observed the same results for oropharyngeal cancer and HNC among individuals with the CT genotype. In contrast, some studies indicated that the T allele exerts a protective effect against HNC. Sailasree et al. [33] demonstrated that the 677 (CT + TT) genotype was associated with a significant 3-fold reduction in the risk of oral cancer (95% CI = 0.16–0.78) in Indian patients. Tsai et al. [31] showed that the MTHFR 677CT and 677TT genotypes exerted protective effects against oral cancer in Taiwan patients (95% CI = 0.54–0.81 and 95% CI = 0.41–0.86, resp.). Moreover, Reljic et al. [25] also reported a decreased risk tendency for 677CT genotype in a Croatian population. However, other studies have shown no significant association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk [12, 20, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 34]. In the stratified analysis with drinking and smoking status, the T allele is also considered as an increased risk factor [24, 32].

This meta-analysis included 23 related studies involving 4,955 cases and 8,805 controls. No significant association was found in all of the genetic models and stratified analysis based on the HWE, ethnicity and study design, and cancer location, expect for few significant risks that were found in thyroid cancer. These results are consistent with two previous meta-analysis on MTHFR gene polymorphism and HNC and oral cancer risk by Boccia et al. [13] in 2009 and Zhuo et al. [52] in 2012, respectively. These meta-analyses included only 9 and 6 studies, respectively. Because of the small sample size and inadequate stratified analysis, further review and meta-analysis with larger sample sizes are necessary to accurately predict the associations between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk.

There were some limitations in this meta-analysis. First, these results are based on unadjusted estimates that lack original data from the included studies. Therefore, the evaluation of the gene-environment interactions during HNC development was limited. Second, MTHFR C677T polymorphism was not analyzed in combination with other related genes involved in folate metabolism, such as methionine synthase (MTR), methionine synthase reductase (MTRR), and adjacent polymorphic locus (A1298C), and the effect of gene-gene interactions of MTHFR C677T polymorphism on HNC development was not illustrated clearly. Third, information of folate intake was not obtained, and the influence of folate on the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk was not explained. Fourth, very few studies included in this meta-analysis involve the smoking and drinking status of patients, and the interaction between gene mutation and effect of environmental factors was not be evaluated accurately. Fifth, heterogeneity existed in all of the genetic models in the total population in our meta-analysis. And the subgroup analyses were conducted to decrease or prevent the occurrence of heterogeneity. The random-effects model was used to estimate the combined effect size when significant heterogeneity was observed.

Despite these limitations, no publication bias was observed. Sensitivity analysis also indicated that the included studies provided consistent and robust results.

5. Conclusion

In summary, no significant association was found between the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and HNC risk. Therefore, large-scale case-control and population-based studies involving potential gene-gene and gene-environment interactions are necessary to investigate the association further.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution

Yu-Ming Niu, Mo-Hong Deng, Wen Chen, and Xian-Tao Zeng performed the literature search, data extraction, and statistical analysis and drafted the paper. Jie Luo supervised the literature search, data extraction, and analysis and reviewed the paper. Yu-Ming Niu, Mo-Hong Deng, Wen Chen, Xian-Tao Zeng, and Jie Luo read and approved the final paper. Yu-Ming Niu, Mo-Hong Deng, and Wen Chen contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledged the support of the subjects who participated in this study. This study was partly supported by the Foundation of Ministry of Education of Hubei Province (D20142102) and Foundation of Hubei University of Medicine (2013GPY07).