Synthesis, Characteristics, and Material Properties Dataset of Bi:DyIG-Oxide Garnet-Type Nanocomposites

Abstract

The fabrication, annealing crystallization processes, and material properties of (Bi,Dy)3(Fe,Ga)5O12:Bi2O3 nanocomposites are investigated and summarized. The stoichiometry of these nanocomposites is optimized for magnetooptic applications using the approach of stoichiometry adjustment (implemented by means of varying RF power densities applied to the sputtering targets used to prepare the nanocomposite thin films). The crystallization processes for all developed batches of as-deposited films are carried out by annealing runs at different temperatures and process durations. This paper describes the methodologies used to optimize the compositions (by calculating the volumetric fractions of excess bismuth oxide to be mixed with the garnet-stoichiometry species during cosputtering processes) and to obtain the optical and magnetooptical properties data and presents the materials properties summary of garnet-bismuth oxide thin film composites as well.

1. Introduction

The development of new photonic materials (including Bi-substituted iron garnet compounds) is required to keep up with the technological demands and challenges of today’s world, especially because most innovative technologies require more advanced, high-performance, stable, functional, and specialized low-cost materials. Bismuth-substituted iron garnets are used as magnetooptic (MO) functional materials for various emerging and existing applications in integrated optics and photonics. However, these are still limited to using bulk garnet layers. Most of the high-speed optical communication systems work in the near-infrared spectral region, where MO garnet materials can perform particularly well. Visible-range devices such as magnetooptic imagers and magnetic field sensing devices often employ Bi-substituted iron garnets due to their extraordinary MO properties. These materials are also very promising for the development of magnetic photonic crystals, magnetoplasmonic crystals, and the production of nanostructured magnetic field landscapes for cold atom manipulation, MO waveguides, and ultrafast optoelectronic devices, such as light intensity switches and modulators for optical communications [1–8]. These substances have been studied since the 1960s, and multiple groups worldwide have been working on customizing the various garnet materials properties by synthesizing garnet films and nanocrystals of different nominal compositions [1, 2, 9–19]. The authors of this paper have previously reported on the synthesis and characterization of Bi-substituted iron garnets of composition type (Bi,Dy)3(Fe,Ga)5O12 and also on their improved MO quality factors. The latter has been achieved by fabricating garnet-Bi2O3 nanocomposites having a combination of remarkable physical properties, which showed great promise for applications in next-generation integrated optics, nanophotonics, and also in reconfigurable photonics [2]. These new garnet-type materials developed by synthesizing garnet-oxide nanocomposites are relatively easy to integrate into the existing integrated optics manufacturing processes and can assist in achieving cost-efficiency by providing the functional materials, which are technologically compatible with the presently used material combinations. The latter is due to (i) the very good compatibility of sputtering processes with many other microfabrication technologies and (ii) the relatively moderate process temperature needed for the synthesis of these garnet-oxide materials. These new garnet materials will have influence on numerous industries in the future, because most of the innovative technologies requiring these advanced materials will be easy to implement and less costly. The dataset generated in this paper is based on our materials research and development activities conducted during the past couple of years in the area of garnet thin films synthesis.

In particular, this paper reports on the summary of materials’ composition optimization, process parameter-related data including the data describing the sputtering and annealing processes, characteristic material-related properties, and also the annealing effects on their optical and MO performance. The characteristic data obtained for several optimized garnet-oxide composites represent the outcomes of our experimental efforts and provide a set of information resources for the production of thin film garnets of high optical quality and impressive MO performance that will likely be required for many advanced integrated optics and photonics applications.

2. Methodologies

2.1. Sample Preparation

Bismuth-substituted (Dy,Ga) doped iron garnet-bismuth oxide composite films (multiple deposition batches) were prepared on glass (Corning 1737) and monocrystalline gadolinium gallium garnet (GGG) substrates using an RF magnetron cosputtering technique in low-pressure (1-2 mTorr) pure-argon plasma with no extra oxygen input. The process parameters and conditions used to deposit (nonreactively) the garnet-oxide composites from two separate targets (oxide-mix-based (BiDy)3(FeGa)5O12 and Bi2O3) are summarized in Table 1. Before depositing any composite garnet layers, the presputtering processes for both garnet and bismuth oxide targets were performed at least for 10–30 minutes to bring them into stable sputtering conditions and also to measure the partial deposition rates of materials. The deposition rates were monitored and measured during all presputtering processes by using a well-calibrated quartz crystal microbalance sensor.

| Process parameters used for thin film garnets preparation | Values & comments |

|---|---|

| Sputtering target compositions | Bi2Dy1Fe5−xGaxO12 (where x = 1 and 0.7) and Bi2O3 (the materials’ purity was 99.99% for all targets) |

| Dimensions of targets | 3′′ dia. × 0.125′′ thick, bonded to 0.125′′ Cu backing plates |

| Sputter gas and pressure | Argon (Ar.), P (total) = 1-2 mTorr |

| Base pressure inside vacuum chamber | P (base) < 1–4 E − 6 Torr |

| RF power densities for garnets | 3.3–7 W/cm2 (150–320 W) |

| RF power densities for Bi2O3 | 0.44–3.96 W/cm2 (20–180 W) |

| Substrate temperature | 250–400°C |

| Partial deposition rates for garnets | 3.5–9.0 nm/min |

| Partial deposition rates for Bi2O3 | 1.2–5.0 nm/min |

| Annealing temperature | 490–680°C |

| Annealing process duration | (<1)–180 minutes, with the ramp-up/ramp-down rates of 3–5°C/min when using a conventional box-furnace-type temperature-controlled air-atmosphere oven-annealing system (Sentro Tech, Inc., USA) |

| Properties characterized | Optical, magnetic, and MO properties of all nanocomposite films |

| Characterization techniques used | Spectrophotometry, custom thin film optimization software, Thorlabs PAX visible-range polarimetry system in conjunction with a custom-made calibrated electromagnet, and transmission-mode polarization microscopy (Leitz Orthoplan). |

| Samples description and composition-adjustment data | Best performance achieved in samples prepared on GGG substrates | Best performance achieved in samples prepared on glass (Corning 1737) substrates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition type | Deposition rate of garnet (nm/min) | Deposition rate of Bi2O3 (nm/min) | Total (garnet + oxide) deposition rate (nm/min) | Vol. % of Bi2O3 in composite films | Faraday rotation per film thickness (deg/µm) | MO figure of merit (Q = 2ΘF/α) (deg) | Faraday rotation per film thickness (deg/µm) | MO figure of merit (Q = 2ΘF/α) (deg) | ||||

| 532 nm | 635 nm | 532 nm | 635 nm | 532 nm | 635 nm | 532 nm | 635 nm | |||||

| 300 W Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12 | 8.33 | — | 8.33 | — | 7.4 | 1.99 | 14.5 | 24.2 | NC ∗ | |||

| 150 W Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12 + 150 W Bi2O3 | 3.77 | 3.66 | 7.37 | 48.85 | 4.05 | 1.25 | 12.14 | 19.46 | NC ∗ | |||

| 300 W Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12 + 60 W Bi2O3 | 8.33 | 1.7 | 10.03 | 16.95 | 4.36 | 1.35 | 10.7 | 22.17 | 3.81 | 1.25 | 6.37 | 12.52 |

| 300 W Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12 + 90 W Bi2O3 | 8.33 | 2.53 | 10.86 | 23.33 | 9.8 | 2.6 | 25.7 | 42.5 | 9.36 | 2.37 | 29.52 | 39.34 |

| 300 W Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12 + 120 W Bi2O3 | 8.33 | 3.2 | 11.53 | 27.75 | 8.31 | 2.26 | 13.34 | 9.44 | 8.22 | 2.05 | 21.75 | 29.38 |

| 300 W Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12 + 180 W Bi2O3 | 8.33 | 4.11 | 12.44 | 33.04 | 1.17 | 0.23 | 1.87 | 1.28 | NC ∗ | |||

- ∗Not characterized.

| Samples description and composition-adjustment data | Best performance achieved in samples prepared on GGG substrates | Best performance achieved in samples prepared on glass (Corning 1737) substrates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition type | Deposition rate of garnet (nm/min) | Deposition rate of Bi2O3 (nm/min) | Total (garnet + oxide) deposition rate (nm/min) | Vol. % of Bi2O3 in composite films | Faraday rotation per film thickness (deg/µm) | MO figure of merit (Q = 2ΘF/α) (deg) | Faraday rotation per film thickness (deg/µm) | MO figure of merit (Q = 2ΘF/α) (deg) | ||||

| 532 nm | 635 nm | 532 nm | 635 nm | 532 nm | 635 nm | 532 nm | 635 nm | |||||

| 200 W Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12 | 5.33 | — | 5.33 | — | 4 | 1.1 | 7.9 | 11.4 | NC ∗ | |||

| 175 W Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12 + 25 W Bi2O3 | 4.77 | 1.65 | 6.12 | 26.96 | 9.5 | 2 | 19.5 | 10.2 | NC ∗ | |||

| 200 W Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12 + 25 W Bi2O3 | 5.33 | 1.65 | 6.98 | 23.64 | 10.12 | 0.85 | 29.2 | 22.1 | 7.88 | 2.0 | 15.5 | 12.05 |

| 250 W Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12 + 25 W Bi2O3 | 7.03 | 1.65 | 7.65 | 19 | 8.2 | 2.05 | 11.3 | 6.22 | NC ∗ | |||

| 300 W Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12 + 25 W Bi2O3 | 8.16 | 1.65 | 9.81 | 16.82 | 7 | 2.1 | 13.3 | 9.98 | 6.3 | 1.9 | 15.0 | 27.82 |

| 320 W Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12 + 20 W Bi2O3 | 8.96 | 1.2 | 10.16 | 11.81 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 8.9 | 12.4 | 4.47 | 1.2 | 10.5 | 19.41 |

- ∗Not characterized.

2.2. Sample Characterizations and Materials’ Performance Data Evaluation

The MO figures of merit for all (annealed) samples were calculated taking into account the measurement errors in the films’ thickness (within estimated ± 5% accuracy) as well as in Faraday rotation angles. The estimated error bars for the MO figure of merit were calculated by considering the achievable maximum and also minimum error-affected Q-factors for each sample, using the upper and lower error limits relevant to the measurements of the films’ thickness as well as Faraday rotation angles. The record-high MO figures of merit (plotted with the error bars shown) obtained in our composite films were reported in [2]. Annealing crystallization studies (using either oven-annealing or rapid thermal annealing processes) of thin films are an important part of modern research in the field of garnet materials. The transformation of amorphous-phase garnets into the micro- or nanocrystalline phase requires careful process development and operator attention and can lead to obtaining samples which are either “underannealed” (showing small or even absent Faraday rotation) or “overannealed” (showing surface damage or material decomposition even with Faraday rotation). One batch of composite-type films of stoichiometry described by approximately 17 vol.% of added extra bismuth oxide was chosen to study the annealing process-dependent evolution of the obtained film properties. This study was conducted by performing the annealing runs for this batch of composite films at three different crystallization temperatures (550°C, 560°C, and 570°C) using a range of annealing process durations (up to 120 minutes). All annealed samples grown on GGG and glass substrates were characterized comprehensively and their recorded performance is summarized in Tables 4 and 5. (The crystal-structure properties of our garnet-oxide composites were characterized using X-ray diffractometry, and the magnetic domain patterns were observed in a range of materials using a transmission-mode polarization microscope. This data was published in other high-impact journals [2, 22].)

| Annealing temperature (°C) | Annealing process duration t (min) | Properties measured at 532 nm | Properties measured at 635 nm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Faraday rotation (deg/µm) | Absorption coefficients (cm−1) | MO figure of merit (deg) | Specific Faraday rotation (deg/µm) | Absorption coefficients (cm−1) | MO figure of merit (deg) | ||

| 550 | <1 | NA ∗ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| 15 | NA ∗ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | |

| 22 | 0.63 | 9040 | 1.39 | 0.033 | 1458 | 0.50 | |

| 27 | 7.2 | 5997 | 24 | 2.062 | 1130 | 36.49 | |

| 30 | 4.23 | 8331 | 10.15 | 0.986 | 1473 | 13.38 | |

| 45 | 5.65 | 6736 | 16.77 | 1.733 | 1484 | 23.35 | |

| 60 | 6.71 | 8563 | 15.67 | 1.828 | 2769 | 13.20 | |

| 90 | 6.35 | 7732 | 16.42 | 1.63 | 2153 | 15.14 | |

| 560 | 4 | NA ∗ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| 7 | 3.60 | 8201 | 8.78 | NC | NC | NC | |

| 12 | 7.04 | 6950 | 20.25 | 2.019 | 1700 | 23.75 | |

| 15 | 6.9 | 6332 | 21.8 | 2.138 | 1382 | 30.94 | |

| 22 | 7.07 | 6145 | 23.01 | 2.062 | 1365 | 30.21 | |

| 26 | 6.51 | 8201 | 15.87 | 1.8 | 2572 | 13.99 | |

| 30 | 6.38 | 7720 | 16.52 | 1.81 | 2162 | 16.74 | |

| 45 | 7.31 | 6477 | 22.57 | 1.938 | 1449 | 26.75 | |

| 52 | 7.07 | 8125 | 17.40 | 2.004 | 3337 | 12.01 | |

| 60 | 6.45 | 9361 | 13.78 | 1.828 | 2347 | 15.57 | |

| 90 | 6.97 | 7232 | 19.27 | NC | NC | NC | |

| 570 | 1 | 2.9 | 8857 | 6.53 | 0.381 | 1867 | 4.08 |

| 2 | 7.03 | 5950 | 23.63 | 1.88 | 1097 | 34.27 | |

| 4 | 7.02 | 6332 | 22.17 | 2.128 | 1021 | 41.60 | |

| 6 | 7.1 | 9315 | 15.25 | 2.119 | 2922 | 14.50 | |

| 8 | 7.56 | 10353 | 14.60 | 2.168 | 3519 | 12.32 | |

| 9 | 6.98 | 8956 | 15.58 | 1.95 | 3213 | 12.13 | |

| 12 | 7.5 | 11428 | 13.12 | 2.076 | 4131 | 10.05 | |

- ∗Not annealed or Faraday rotation was below detection limit. NC: not characterized.

| Annealing temperature (°C) | Annealing process duration t (min) | Properties measured at 532 nm | Properties measured at 635 nm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Faraday rotation (deg/µm) | Absorption coefficients (cm−1) | MO figure of merit (deg) | Specific Faraday rotation (deg/µm) | Absorption coefficients (cm−1) | MO figure of merit (deg) | ||

| 550 | <1 | NA ∗ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| 13 | NA ∗ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | |

| 15 | 5.85 | 7564 | 15.46 | NC | NC | NC | |

| 22 | 6.42 | 7221 | 17.78 | 2.024 | 1765 | 24.08 | |

| 27 | 6.52 | 6671 | 19.54 | 2.41 | 1588 | 28.90 | |

| 30 | 6.85 | 7072 | 19.37 | 2.35 | 1830 | 24.46 | |

| 45 | 7.04 | 7495 | 18.78 | 2.395 | 2091 | 21.82 | |

| 60 | 6.82 | 7495 | 18.19 | 2.343 | 1867 | 23.90 | |

| 90 | 6.47 | 7228 | 17.90 | 2.31 | 1828 | 24.07 | |

| 560 | 4 | NA ∗ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| 7 | 6.28 | 8209 | 15.30 | NC | NC | NC | |

| 12 | 6.54 | 7942 | 16.46 | 2.34 | 2026 | 23.09 | |

| 15 | 6.74 | 8163 | 16.51 | 2.071 | 2082 | 19.89 | |

| 22 | 6.57 | 7911 | 16.60 | 2.195 | 1857 | 23.64 | |

| 26 | 6.74 | 7682 | 17.55 | 2.08 | 1943 | 21.41 | |

| 30 | 7.2 | 6568 | 21.93 | 2.247 | 1941 | 23.15 | |

| 45 | 6.76 | 7858 | 17.20 | 2.73 | 2103 | 25.96 | |

| 52 | 6.67 | 7949 | 16.78 | 2.185 | 2151 | 20.32 | |

| 60 | 7.1 | 6027 | 23.56 | 2.219 | 1821 | 24.37 | |

| 570 | 1 | 6.54 | 7873 | 16.61 | 2.07 | 2145 | 19.30 |

| 2 | 6.21 | 8167 | 15.20 | 2.257 | 2119 | 21.30 | |

| 4 | 6.65 | 8068 | 16.48 | 2.23 | 2214 | 20.15 | |

| 8 | 7 | 6881 | 20.35 | 2.267 | 1903 | 23.83 | |

| 12 | 6.96 | 8064 | 17.26 | 2.295 | 2532 | 18.13 | |

- ∗Not annealed or Faraday rotation was below detection limit. NC: not characterized.

The evaluation of optical and magnetooptical properties can only be partially helpful to understand the crystallization kinetics relevant to these garnet-type thin film materials if the extent of crystallization is quantified (in a simplified way) as the ratio of the specific Faraday rotation measured in films after running any given annealing process, to the maximum specific Faraday rotation at the same wavelength achieved in any given material/substrate system after running the process at the same annealing temperature with the “best-known” parameters. All specific Faraday rotation data obtained from the samples deposited onto GGG substrates were measured in the remnant magnetization states, in order to exclude the paramagnetic effects of 0.5 mm thick GGG substrates, which led to measuring slightly increased Faraday rotation angles when placed in the electromagnet’s saturation field of up to 2.5 kOe. For samples deposited onto Corning 1737 glass substrates, Faraday rotation data was taken at the saturation magnetization, even though all films maintained about 90% of Faraday rotation after being removed from the electromagnet. The data obtained may not be sufficient to derive accurately the activation energy of crystallization for Bi-substituted iron garnets and garnet-type nanocomposites; however these data reveal the general character and thermal dynamics of the annealing-induced isothermal-crystallization processes in these materials. A significant amount of characterization work was performed during this study, and the authors believe that it can provide a good source of data for further research efforts on the development of new garnet materials.

3. Discussion

Several batches of garnet-oxide composite-type thin films deposited onto both GGG and glass substrates were characterized and evaluated comprehensively. The results obtained describe a very promising class of garnet thin films of composition type (BiDy)3(FeGa)5O12.

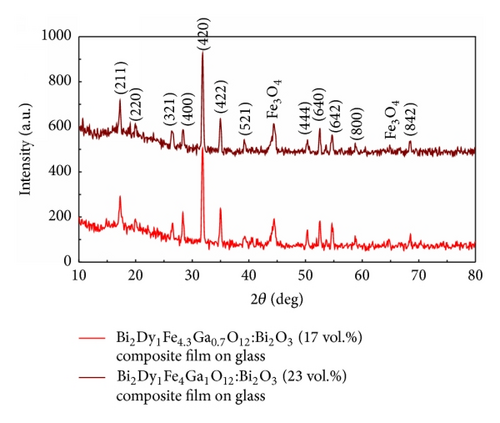

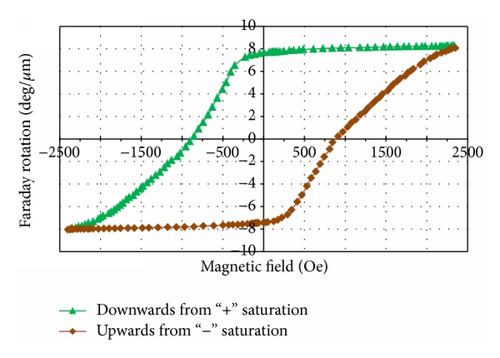

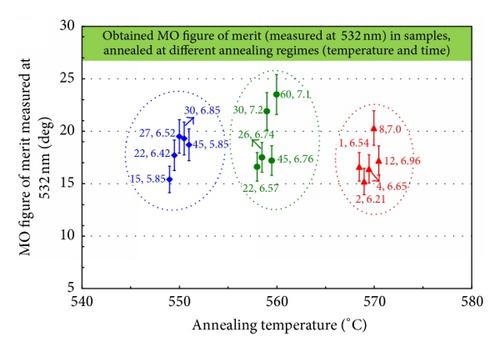

Good crystallinity properties, surface quality, and attractive magnetic and MO performance characteristics were observed in most sample batches. The data (presented in Tables 1–5) describe the methodology, parameters, and conditions relevant to the synthesis of performance-optimized garnet-oxide composite-type thin film materials and the ways of obtaining materials with specific properties. Figure 1 shows a glimpse into the obtained superior microstructural, magnetic, and magnetooptical properties in optimally annealed composite-type garnet films; (a) shows the XRD datasets of garnet-oxide layers of composition type (BiDy)3(FeGa)5O12:Bi2O3 prepared on Corning 1737 glass substrates. The strong peaks for (221), (220), (321), (400), (420), (422), (521), (444), (640), (642), (800), and (842) reflections planes originated at the 2θ (°) values 17.25, 19.95, 26.55, 28.35, 31.8, 34.95, 39.25, 50.35, 52.55, 54.65, 58.75, and 68.45, respectively, confirmed their good crystalline quality and also the presence of garnet phase with body-centered cubic lattice type. The diffraction peak found at 44.5° has revealed the XRD signature of Fe3O4 according to a search of JCPDS catalogue (JCPDS powder diffraction file number 28-0491) [23] which confirmed the hypothesis having larger visible-range optical absorption of sputtered garnet films [2]. The lattice parameter of crystallized Bi2Dy1Fe4Ga1O12:Bi2O3 (23 vol.%) grown on GGG (111) substrate was calculated using the formula derived from the combination of Bragg’s equation and d-spacing expression and the calculated (averaged) lattice constant was found about 12.579 Å [22, 24]. The predicted stoichiometry for the garnet-oxide composite layer was Bi2.4Dy0.6Fe4Ga1O12, and this was confirmed by EDX microanalysis results [20, 22]; (b) the measured nearly square hysteresis loop of Faraday rotation with high coercivity in Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12:Bi2O3 composite film (having an estimated 24 vol.% of excess Bi2O3) grown on a Corning 1737 glass substrate, showing different dynamics of the magnetization switching process in comparison with other films from the same batch sputtered onto GGG (111) substrates, revealed significant microstructural differences in layers grown onto different substrates type; and (c) shows the data on the time and temperature-dependent evolution of the measured MO figure of merits obtained in Bi2Dy1Fe4.3Ga0.7O12:Bi2O3 (17 ± 2 vol.%) films prepared on glass substrates. The data point distributions within data clusters shown within the circles followed the expected trends of MO quality factors for this material type at each of the optimized annealing temperatures.

4. Conclusion

We have prepared and characterized a large number of garnet-oxide composite-type thin films grown on both GGG and glass substrates during a study conducted in the area of magnetooptic functional materials reported previously in a string of our publications. The properties dataset of garnet-oxide composite materials presented as well as the data related to the evolution of the optical and magnetooptical properties of particular batches of composite films occurring during annealing processes can be used as a guide for designing a range of optimized garnet-type thin film materials. This paper will be a useful reference for researchers working to produce functional magnetooptic garnet materials with application-specific material composition and properties suitable for a range of applications in integrated optics and photonics.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the extensive support for this work provided by the Electron Science Research Institute (ESRI), the Faculty of Health, Engineering and Science (FHES), Edith Cowan University (ECU), WA, Australia.