Conspicuity Research on the Highway Roadside Objects: A Simulator Study

Abstract

In a monotonous travelling environment, the single-vehicle run-off-roadside accidents occur easily. The injuries and fatalities caused by those accidents are significant components of the annual road casualties. The causation is the complex interaction of the visual effects on the roadside objects’ conspicuity. So the conspicuity enhancement needs to be considered in the roadside objects design to provide a temporary restoration of alertness and vigilance to drivers. Factors contributing to the conspicuity of the roadside objects were analyzed in this paper. A driving simulator study was conducted in order to extrapolate the relationship between the legibility distances and the objects and to quantify the conspicuity of the roadside objects different in basic features. The conclusions of this paper were firstly, a significant correlation existed between the mean legibility distance and the object’s size. The mean legibility distance was in a significant exponential proportion to the object’s size. Secondly, the triangle’s legibility was better than that of the rectangle and round contours. Only when the roadside object was combined with the suitable contour and size did the best visual quality come. To some extent, the conclusions could provide theoretical tools and strategies to optimize the dimensional design of the roadside objects in order to maintain the roadside safety.

1. Introduction

A typical highway driving task may not contain a complex cognitive process, but in a monotonous travelling environment, the single-vehicle run-off-roadside accidents occur easily [1]. Most of the accidents are collisions to the roadside human-made objects, such as the ditches, utility poles, crash cushions, embankments, or signposts. The injuries and fatalities caused by those collisions are significant components of annual road casualties. For example, in the United States, the single-vehicle run-off-roadside accidents result in over a million highway crashes with the roadside objects every year. The latest accident statistics in Washington State indicated that roadside crashes account for one-third of the total highway fatalities and about one-fourth of the traffic accidents were associated with vehicles running off the road on the highways. Such accidents accounted for about one-third of all highway fatalities, with an estimated societal cost of over $80 billion a year [2]. Also, the accident statistics in the European Union in 1998 indicated that 33.8 percent of all fatalities occurred when the single vehicles left the roadside unintentionally and approximately two-thirds of fatalities on the rural roads were caused by it [3, 4].

The causation of these accidents is the complex interaction of the visual effects on the roadside objects’ conspicuity. Among the run-off-roadside accidents, most were associated with the driving inattention and drowsiness, which triggered the visual distractions, visual fatigue, or looking-but-failing-to-see faults [5]. Loo [6] noted that the field dependent drivers were less skilled at detecting the roadside objects embedded in visual scenes, especially when the roadside objects were in the unconspicuous contours in a monotonous highway environment [7]. Several findings showed that the frequencies of the run-off-roadside accidents could be significantly reduced by enhancing the roadside objects’ conspicuity [8]. So the roadside objects should be in great conspicuity to ensure the physical visual condition [9–11]. The conspicuity enhancement needs to be considered in the dimensional design of the roadside artificial objects to provide a temporary restoration of alertness and vigilance to the drivers [12]. But within the international community, no clear agreement has been reached on how these roadside objects should be dimensioned [13]. This further highlights the task to quantify the conspicuity of the roadside objects [14, 15].

Studies to quantify the conspicuity can be linked to the studies on the objective legibility distance and the subjective comfort preference of the viewers. Factors contributing to the roadside objects’ legibility are their basic features and the context in which they are embedded [16–21]. The basic features include the sizes, the colors, and the contours of the roadside objects. And the embedded context includes the contrast with the immediate surroundings, their placement, and the complex interaction with the traffic background and the drivers’ requirements or expectations. Subjective comfort assessment on the conspicuity can be quantified via the questionnaires.

So the objective of this exploratory study was to quantify the conspicuity of the roadside objects. To do this, two primary steps must be done: firstly, to extrapolate the relationship between the legibility distances and the objects and, secondly, to assess the subjective comfort preference of the roadside objects varied in the basic features. The conclusions could provide theoretical tools and strategies to optimize the dimensional design of roadside objects. The rest of the paper was organized as follows. Section 2 introduced the method to conduct the conspicuity test. And Section 3 analyzed the experimental data of the test. And conclusions and discussions were given in Section 4.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Forty participants were recruited to drive in the simulated scenario. 28 of them were males. The mean age was 26 years (SD = 2). Each participant was a licensed driver with at least 3 years’ driving experience. All of them had a minimum visual acuity of 20/40, wearing corrective lenses if necessary. Psychoactive substances, such as the caffeine or nicotine, were forbidden to be taken before or during the formal experiment. Each participant received the monetary compensation for their involvement in the experiment.

2.2. Apparatus

The chronic lack of detailed data on the conspicuity of the roadside objects has been an obstacle to conduct the conspicuity research on the roadside objects. Supposing the data on the conspicuity can be collected, the best option is to conduct this investigation in a real car travelling through a real highway section. However, such trials are not replicable, as the identical circumstances cannot be replicated for other tests because of the changing traffic and weather. So the controlled situations for the conspicuity test are preferred. A driving simulator, an interactive device based on PC programs, is recognized as an effective tool to conduct the conspicuity test [22, 23]. The external interfering elements can be eliminated or controlled just by the simple parameter modification in the scenarios [24–26]. Studies have proven that the legibility distance measured via a simulator agrees with the field legibility distance [27]. In additional, the subjective comfort preference of the roadside objects can be easily measured to quantify the conspicuity [28].

The simulator AutoSim AS 1600 used in this study is a fixed-based driving simulator composed of a complete automobile, fully functional pedals and dashboard, and a large screen showing highway images projected by an RGB projector. It provides a realistic visual, sound, and vibration system. Simple desktop simulators, which are often implemented using a standard PC computer monitor for the visual display, are on the other end of the range. During a simulation test, the location and speed of the vehicle on the x-, y-, and z-axes are recorded by the GPS tracking software and displayed on the GPS real-time tracking device window. And a loudspeaker is mounted on the wheel to receive the driver’s real-time feedback. Room temperature and lighting are controlled. Figure 1 showed that a tester drove in the simulator.

2.3. Simulation Scenarios

The simulation scenarios in this study were based on a 10 km-long corridor of the Jing-jin highway, which is started from the 4th east ring of Beijing, China. It is a six-lane state highway containing a side slope with typical grassland covered on the topography (as shown in Figure 2). The lane widths are obtained from the road controlling authority, and the road markings are consistent with Chinese Transport Agency guidelines. The driving speed is limited to 120 km/h.

Due to the high-traveling speed, all the roadside objects are identified by the spatial contours, which is the key information for drivers to process when driving. Three contours, the triangle, the rectangle, and the round, frequently appear on the roadside as the sign supports, bridges, cut-type slopes, ditches, fences, utility poles, guardrails, crash cushions, breakaway posts, or embankments and so forth [29]. Accordingly, three simulated scenarios, classified by these three roadside contours, were created. In each scenario, five roadside objects, which were in the identical contours but varied sizes, were structured on the cenetr of the slope in sequence. And the interval between each two adjacent objects under the limited speed was calculated according to the short-term memory time—the duration time for holding the relevant information active in mind for 60 seconds at most [30]. The design parameters of the three scenarios were described in Table 1.

| Simulated scenario | Contours | Sizes (m2) | Interval (km) | Highway length (km) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rectangle | 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | 2 | 10 |

| 2 | Triangle | 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | 2 | 10 |

| 3 | Round | 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | 2 | 10 |

- (1)

Set the roadside objects in a sensitive visual zone. The most sensitive distance off the driveway is testified to be ranged from 15 to 25 meters [31]. In this paper, the distance off the driveway to the roadside objects was 15 meters.

- (2)

Set the color contrast with the immediate surroundings conspicuously. Color contrast refers to the perceptual difference in two adjacent colors. Most studies support the notion that color contrast has only a small effect on the conspicuity [32–34]. The 24-color wheel theory (as shown in Figure 3) identifies that conspicuity appears when the colors exactly opposite to each other are combined together [35]. So, in this paper, the objects were textured in red purple in contrast to the green slope to bring a maximum effect on the conspicuity.

2.4. Procedure

During the preexperiment, each tester was given a brief overview of the experimental activities and practiced for 10–15 minutes to get familiar with the scenarios and rules. At the formal experiment of each scenario, the tester was instructed to drive in the simulator. Factors contributing to the conspicuity—the dynamical legibility distance, in additional to the comfort assessment on the roadside object—were measured under four given speeds, 60 km/h, 80 km/h, 100 km/h, and 120 km/h. A short break was offered after each scenario in case of the driving fatigue.

2.5. Dependent Variables

The in-vehicle data collection system provided the capability to store data on a computer in the form of one line of numerical data every 0.1 second during a data run. The specific measures collected were as follows.

3. Results

The data on the legibility distances and the comfort assessments under given speed and contours were used to analyze the conspicuity of the roadside objects in detail.

3.1. Legibility Distance

The data on the mean legibility distances of the 15 roadside objects were depicted in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. Firstly, the Pearson correlation test was conducted to check the correlation between the mean legibility distance, the size, and the driving speed. The results presented in Table 6 showed that no significant correlation existed between the mean legibility distance and the speed; but a significant correlation existed between the mean legibility distance and the size of the contours.

| Contour | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 136.58 | 529.10 | 846.98 | 1225.88 | 1761.12 |

| Rectangle | 123.93 | 514.48 | 762.77 | 1129.70 | 1606.03 |

| Round | 103.63 | 493.01 | 647.66 | 1128.78 | 1559.14 |

| Contours | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 122.87 | 524.56 | 766.5 | 1397.16 | 1764.90 |

| Rectangle | 117.65 | 516.37 | 729.91 | 1236.19 | 1561.38 |

| Round | 107.87 | 505.81 | 696.44 | 1202.48 | 1517.41 |

| Contours | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 123.72 | 532.65 | 757.29 | 1347.34 | 1764.90 |

| Rectangle | 120.82 | 524.62 | 744.64 | 1248.22 | 1744.74 |

| Round | 113.86 | 500.81 | 732.43 | 1162.23 | 1642.60 |

| Contours | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 121.38 | 514.18 | 756.34 | 1331.08 | 1776.47 |

| Rectangle | 112.77 | 507.39 | 749.48 | 1212.79 | 1753.18 |

| Round | 106.43 | 482.58 | 717.82 | 1065.30 | 1701.53 |

| Legibility distance | Contour size | Driving speed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legibility distance | |||

| Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.977 | 0.018 |

| Significance | — | 0.000 | 0.893 |

| Contour size | |||

| Pearson correlation | 0.977 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| Significance | 0.000 | — | 1.000 |

| Driving speed | |||

| Pearson correlation | 0.018 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Significance | 0.893 | 1.000 | — |

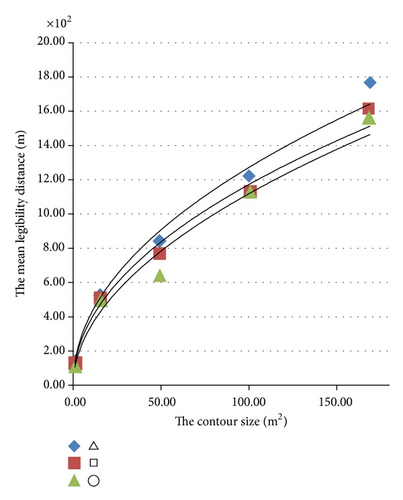

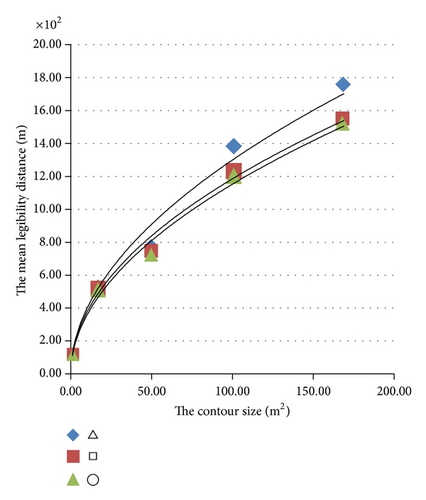

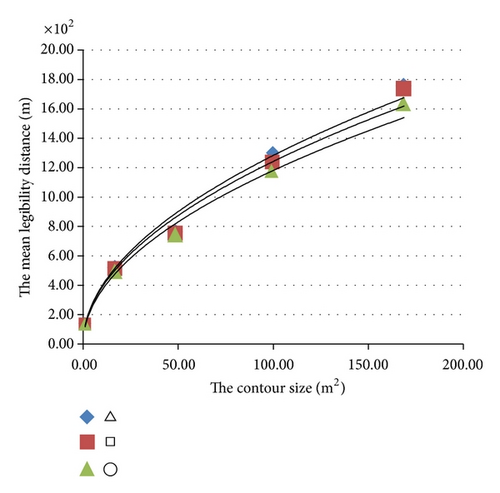

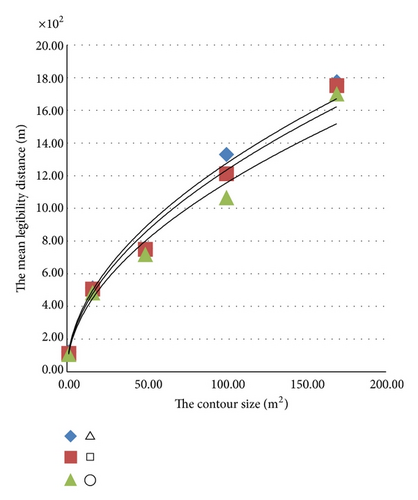

The mathematical relationship between the mean legibility distance and the size under different speed was analyzed by SPSS 16.0. Functions between them were given in Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7. Every function curve was monotone increasing, with a high fitting of R2. Moreover, the mean legibility distance was in a significant exponential proportion to the size.

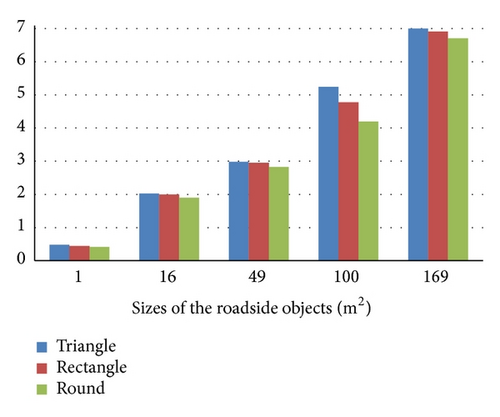

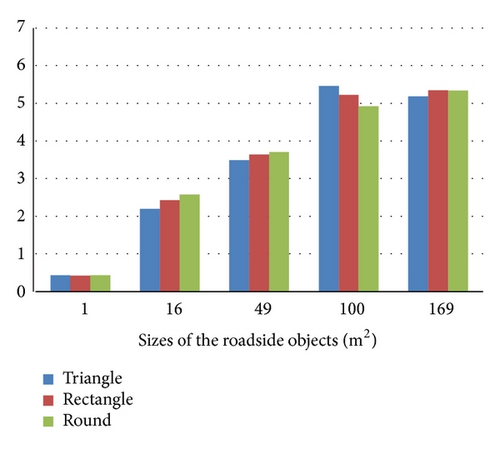

So the legibility assessment results of all the roadside objects were presented in Table 7 and Figure 8. It is depicted that the triangle contour in size 169 m2 won the highest legibility score, while the round contour in size 1 m2 was rated the least legible with an average rating of 0.42. The same results were found under the speeds 60 km/h, 80 km/h, and 100 km/h. The triangle’s legibility was testified to be the best among the three given contours in same sizes.

| Contours | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 0.48 | 2.03 | 2.98 | 5.24 | 7.00 |

| Rectangle | 0.44 | 2.00 | 2.95 | 4.78 | 6.91 |

| Round | 0.42 | 1.90 | 2.83 | 4.20 | 6.70 |

- *1: not at all legible. 7: extremely legible.

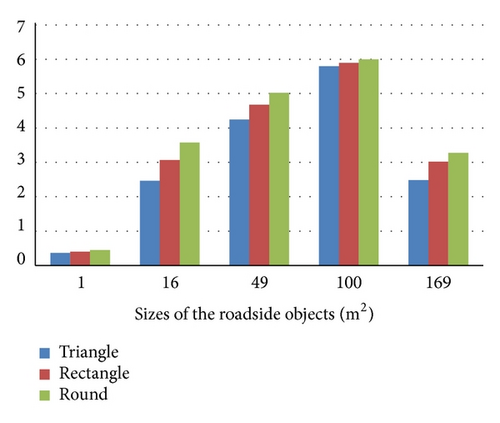

3.2. Comfort Assessment

Under the speed 120 km/h, the comfort assessment regarding the experimental roadside object was fulfilled via the in-driving questionnaire, with the results shown in Table 8 and Figure 9. It is seen that the rectangle contour in size 100 m2 won the best comfort preference among all the roadside objects with an average of 6.1, while the triangle contour in size 1 m2 won the poorest comfort preference with an average rating of 0.36. The same results were found under the speeds 60 km/h, 80 km/h, and 100 km/h. When the sizes were smaller than 100 m2, the rectangle and round contours could easily win the comfort preference, not the triangle contour, but the comfort preference was not monotone increasing to the sizes. When the sizes of the objects were larger than 100 m2, the comfort preference decreased gradually.

| Contours | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 0.36 | 2.46 | 4.25 | 5.8 | 2.48 |

| Rectangle | 0.40 | 3.07 | 4.68 | 5.9 | 3.02 |

| Round | 0.45 | 3.58 | 5.02 | 6.0 | 3.28 |

- *1: not at all comfortable. 7: extremely comfortable.

3.3. Conspicuity Result

According to (3), the conspicuity results of the roadside objects based on the legibility and the comfort assessment were shown in Table 9 and Figure 10. It is seen that the triangle contour in size 100 m2 was found to be the most conspicuous object with the comfort preference. Although the triangle contour, compared with the rectangle and round contours, was more conspicuous, its comprehensive conspicuity score was reduced because of its uncomfortable appearance. The same results were found under the speeds 60 km/h, 80 km/h, and 100 km/h.

| Contours | Sizes of the roadside objects (m2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 49 | 100 | 169 | |

| Triangle | 0.43 | 2.20 | 3.49 | 5.47 | 5.19 |

| Rectangle | 0.43 | 2.43 | 3.64 | 5.23 | 5.35 |

| Round | 0.43 | 2.57 | 3.71 | 4.92 | 5.33 |

4. Conclusions and Discussions

Several conclusions were given in this section to summarize the investigation of this paper. Firstly, the results showed that no significant correlation existed between the mean legibility distance and the speed, but a significant correlation existed between the mean legibility distance and the object’s size. The mean legibility distance was in a significant exponential proportion to the object’s size. Secondly, the comprehensive conspicuity of the roadside objects different in contours and sizes was quantified by the objective or subjective measurement on the objects’ legibility and the comfort preference. The results confirmed the empirical theory that the triangle’s legibility but not the conspicuity was better than those of the rectangle and round contours. Only when the roadside object was combined with the suitable contour and size did the best visual quality come. The rectangle or round contours were preferred in the design and management of the roadside objects when the object was in a huge size. To some extent, the conclusions could provide theoretical tools and strategies to optimize the dimensional design of the roadside objects in order to maintain the roadside safety.

Further research is to be conducted to enrich its research scope.

Firstly, the experiment could be conducted among the elders because the current mean age of the participants was 26 years old. The effects of age on information-processing time and short-term memory stressed the elders due to a reduction in the minimum visibility distance and perception-reaction time required for certain signing situations. So the research plans should also be made to test the effects on older drivers of the roadside objects.

Secondly, besides the several basic features of the roadside objects (such as contours and sizes), other factors contributing to the conspicuity should also be considered in the simulated scenario. The color of the roadside object played an important role in conveying conspicuity. Therefore, it would be more useful to consider the effect of colors on the traffic safety. Additionally, the distinct contours of roadside structures should have a positive effect on the driving performance by allowing a temporary restoration of alertness and vigilance or leading to increased awareness of traffic route information, or enhancing the driving comfort due to the earlier detection of roadside objects and better visibility, although the novelty effects due to contours might wear off over time. In this paper, only three simple common contours of the roadside objects were selected; other complicated and monogram objects in contours could be investigated on the conspicuity further.

Thirdly, it is important to note that the real world varies from the simulator. There are gaps between the simulated and actual traffic scenarios, such as the external traffic disturbance, surroundings, and road condition. So the validation and modification work on several parameters will be conducted in actual traffic scenarios further.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 51208008). Their support is gratefully acknowledged.