Recent Developments in Homogeneous Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water and Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

This paper reports on recent developments in homogeneous Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) for the treatment of water and wastewater. It has already been established that AOPs are very efficient compared to conventional treatment methods for degradation and mineralization of recalcitrant pollutants present in water and wastewater. AOPs generate a powerful oxidizing agent, hydroxyl radical, which can react with most of the pollutants present in wastewater. Therefore, it is important to discuss recent developments in AOPs. The homogeneous AOPs such as O3, UV/O3, UV/O3/H2O2, and UV/H2O2, Fe2+/H2O2, UV/Fe2+/H2O2 on the degradation of pollutants are discussed in this paper. The influence on the process efficiency of various experimental parameters such as solution pH, temperature, oxidant concentration, and the dosage of the light source is discussed. A list of contaminants used for degradation by various AOPs and the experimental conditions used for the treatment are discussed in detail.

1. Introduction

Wastewater is water that contains various pollutants, which means it cannot be used like pure water and should not be disposed of in a manner dangerous to humans, living organisms, and the environment. Water pollution has a serious impact on all living creatures, adversely affecting water use for drinking, household needs, recreation, fishing, transportation, and commerce. It has been estimated that the total global volume of wastewater produced in 1995 was in excess of 1,500 km3 [1]. On July 28, 2010, the United Nations General Assembly declared safe and clean drinking water and sanitation a human right essential to the full enjoyment of life and all other human rights [2]. It is a concern that nearly 900 million people in the world do not have access to safe drinking water. Approximately 1.5 million children under five die every year as a result of diseases linked to a lack of access to water and sanitation as indicated by World Health Organization (WHO) [3]. It was estimated that about 1.8 million deaths annually are due to lack of access to safe drinking water and poor sanitation.

In the past, economically viable chlorination has been used for water treatment. Yet the potentially adverse health effects of the by-products formed, together with raised drinking water standards, have led researchers to search for effective and economical alternatives to chlorinating drinking water [4, 5]. Various wastewater treatment processes have been tried using physical, chemical, and biological methods [6–12]. Some of these methods have disadvantages, however, and cannot be applied for large scale treatment. For example, one drawback of precipitation methods is sludge formation. Chemical coagulation and flocculation use a large amount of chemicals and the generated sludge may contain hazardous materials, so sludge disposal remains a problem. Adsorption techniques have been used widely for the removal of various water and wastewater pollutants. Their disadvantage is that the pollutants may only transfer to the adsorbent, which needs to be regenerated regularly, resulting in additional costs. Membrane technologies such as ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis have been used for the full scale treatment and reuse of water and chemicals. Yet these methods have several operational difficulties in addition to high capital costs. Thus physical methods may not be suitable for the complete removal of pollutants from the environment. Similarly, two different basic biological wastewater treatment methods have been employed: aerobic and anaerobic treatments. These methods also do not completely remove the high concentration of pollutants present in wastewater. Other biological methods involve cost-effectiveness or operational difficulties, making biological means unsuitable for wastewater treatment.

Among the chemical methods, oxidation is efficient and applicable to large scale wastewater treatment. Generally air, oxygen, ozone, and oxidants such as NaOCl and H2O2 are used for chemical treatment. The oxidation potential of some of the oxidants is listed in Table 1. The basic chemical oxidation process with air and oxygen also occurs in nature, but it is no longer sufficient for highly polluted wastewater. Therefore there is a significant need to develop a wastewater treatment process which can remove the pollutants effectively by a simple method.

| Substance | Potential (V) |

|---|---|

| Hydroxyl radical (∙OH) | 2.86 |

| Oxygen (O) | 2.42 |

| Ozone molecule (O3) | 2.07 |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | 1.78 |

| Chlorine (Cl2) | 1.36 |

| Chlorine dioxide (ClO2) | 1.27 |

| Oxygen molecule (O2) | 1.23 |

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for wastewater treatment have received a great deal of attention in recent years. AOPs generate the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH) to degrade the recalcitrant chemicals present in wastewater [13–15]. These OH radicals attack the most organic molecules rapidly and nonselectively. The versatility of AOPs is also enhanced by the fact that they offer various alternative methods of hydroxyl radical production, thus allowing a better compliance with specific treatment requirements. The eco-friendly end product is the special feature of these AOPs, which are more efficient as they are capable of mineralizing a wide range of organic pollutants. Interestingly, AOPs can make use of solar energy rather than artificial light sources. The latter rely on high electrical power, which is costly and hazardous.

AOPs such as ozonation (O3), ozone combined with hydrogen peroxide (O3/H2O2) and UV irradiation (O3/UV) or both (O3/H2O2/UV), ozone combined with catalysts (O3/catalysts), UV/H2O2, Fenton and photo-Fenton processes (Fe2+/H2O2 and Fe2+/H2O2/UV), and the ultrasonic process and photocatalysis have been successfully used for wastewater treatment [16–23]. This review reports on recent advances in the aforementioned AOPs for water and wastewater treatment. The authors discuss the principle of hydroxyl radical generation from each AOP, the influence of various experimental parameters, and their consequences for the treatment process.

1.1. Ozone Based Advanced Oxidation Processes

(i) Ozonation. Ozone is an environmentally friendly oxidant since it decomposes into oxygen without producing self-derived by-products in the oxidation reaction. It is widely used in the purification of drinking water, the treatment of wastewater and process water, the sterilization of water in artificial pools, and so forth. In an ozonation process, two possible oxidizing actions may be considered. The first or direct method involves the reaction between ozone dissolved compounds. The second is known as the radical method because of the reactions between the hydroxyl radicals generated in ozone decomposition and the dissolved compounds [24]. Some oxidation products are refractory to further oxidative conversion by means of ozone, thus preventing a complete abatement of TOC. Yet the high energy cost of direct ozonation limits many practical applications. To increase the efficiency of the ozonation process, the ozone is combined with H2O2 and UV light, which is expected to increase the removal rate substantially by producing more hydroxyl radicals in the treatment system.

(iv) O3/UV/H2O2. This combined process may generate hydroxyl radicals in different ways as mentioned in (1)-(2). It is considered to be the most effective treatment process for highly polluted effluents.

1.2. UV/H2O2 Process

The UV/H2O2 process is a homogeneous advanced oxidation process employing hydrogen peroxide with UV light. Hydrogen peroxide requires activation by an external source such as UV light and the photolysis of hydrogen peroxide generates the effective oxidizing species hydroxyl radical (•OH). The rate of photolysis of H2O2 depends directly on the incident power or intensity. The hydrogen peroxide decomposition quantum yield is 0.5 at UV (254 nm) irradiation. Solar light could also be used as a radiation source but the rate of photolysis may be low compared to UV light. In this process the dosage needs to be optimized, however, since excess H2O2 may scavenge hydroxyl radical.

1.3. Heterogeneous AOPs

1.3.1. Catalytic Ozonation Process

Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation is a novel type of AOP that combines ozone with the adsorptive and oxidative properties of solid phase catalysts to decompose pollutants at room temperature. Catalytic ozone decomposition at room temperature is advantageous compared to thermal decomposition in terms of energy conservation since it does not require large volumes of air to be heated. It is therefore a promising advanced oxidation technology for water treatment.

1.3.2. Photocatalysis

Heterogeneous photocatalysis through illumination by UV or visible light on a semiconductor surface generates hydroxyl radicals. The photocatalyst can be used successfully for the effective treatment of pollutants in water and wastewater.

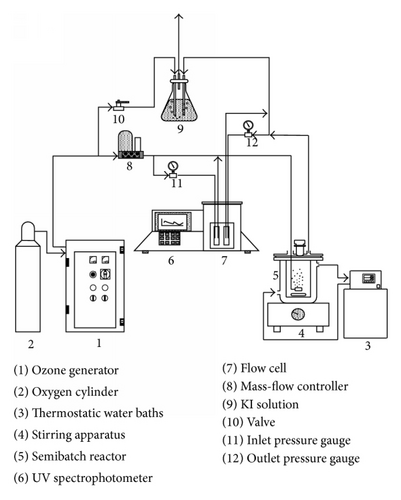

2. Ozone Based AOPs

As noted above, ozone reacts with various organic and inorganic compounds in an aqueous solution, either by direct reaction of molecular ozone or through a radical mechanism involving hydroxyl radical induced by the ozone decomposition. Figure 1 shows the experimental setup of the ozonation process. This process is strongly influenced by a number of experimental parameters such as solution pH, influent ozone dosage rate, and temperature. The primary reactions initiated by ozone in water are strongly pH dependent. Ozone reacts with organic substrate at low pH as a molecular form, but at high pH it decomposes before reacting with the substrate. Ozone decomposition is catalyzed by hydroxide ions and proceeds more rapidly with increasing pH, eventually to produce hydroxyl radicals. The influence of solution pH on ozonation process efficiency has been observed in a number of studies. For example, Jung et al. investigated the effect of pH on the ozonation of ampicillin from pH 5 to 9, concluding that higher pH conditions are necessary for effective removal [66]. They also discussed how changing pH influences the charge of some specific functional groups on the ozonation process. Can and Gurol investigated the effect of solution pH on the ozonation of humic substances. They found that rapid ozone decomposition was caused by the interaction of ozone with the humic substance, which eventually yielded hydroxyl radical [67]. They further noted that increasing humic substance concentration facilitates fast ozone decomposition into hydroxyl radical. Similarly, the influence of solution pH and temperature on the ozonation of six dichlorophenols was investigated by Qiu et al. [68]. They revealed that the changing solution pH was strongly influenced the decomposition and the rate was increased by raising the hydroxyl radical concentration from acidic to alkaline pH [68].

Although hydroxyl radical formation is highly favourable to produce more •OH radicals by ozone self-decomposition at pH 10, a portion of carbonate or bicarbonate ion formation could play a key scavenging role in trapping •OH radicals, appreciably decreasing the degradation rate. Wu et al. found that 2-propanol degradation decreases at pH 10 and suggested bicarbonate formation as the possible reason for the decreasing degradation rate at this pH [19]. Other studies reached quite different results. Moussavi and Mahmoudi noted a higher removal rate of Reactive Red 198 azo dye in an ozonation process at pH 10 [69]. Interestingly, Begum and Gautam noted that as the pH increased from 9 to 12 in the ozonation process the endosulfan and lindane removal rate also increased [70]. In contrast to the above results other authors noted that the oxidation rate is relatively independent of solution pH values [71]. Hong and Zeng found that the rates of pentachlorophenol decomposition were very similar between pH 7 and 12, indicating then negligible influence of pH values [72]. These results clearly showed that the nature of pollutants being used for the ozonation process played an important role besides the favourable hydroxyl radical formation at higher pH. Based on the above discussion it is concluded that the influence of pH on the ozonation process needs to be optimized.

Several investigations were conducted into the effect of temperature on the ozonation process. Changing the temperature generally influences the ozonation process in two ways. Firstly, when the temperature increases, the solubility of ozone may decrease, since Henry’s law coefficient of ozone increases with rising temperatures. Secondly, raising the temperature increases the activation energy which may positively assist the ozonation process. Muruganandham et al. noted that N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP) mineralization was substantially increased when the ozonation temperature rose from 5 to 50°C [13]. They also concluded that the increasing removal rate due to the higher reaction temperature is not balanced by the lower solubility of ozone. Similar results were noted in other ozonation studies [68, 73–76]. Some researchers found, however, that increasing temperature in the ozonation process decreases the removal rate by decreasing the ozone solubility [77, 78]. Interestingly, Ku et al. found that the reaction rates of phorate decomposition were relatively independent of solution temperatures and pH values [71]. Yet some mineralization formation of products such as phosphate and carbonate was increased significantly with raised solution temperature.

Another important experimental parameter influencing ozonation process efficiency is influent ozone dosage. Treatment cost increases with a higher applied ozone dose, so it is necessary to optimize this dosage. For semibatch experiments, increasing the ozone dosage will enhance the mass transfer rate of ozone from the gas phase to the liquid phase, which is expected to enhance the degradation rate appreciably. As the ozone concentration in the liquid phase is saturated, however, ozone mass transfer is limited at a very high ozone dosage [79]. Many authors investigated how the influent ozone dosage affects the degradation rate in the ozonation process within different experimental parameters. Muruganandham et al. reported that the optimal ozone dosage for NMP mineralization is 18.4 mg min−1 [13]. Moreover, an ozone dosage of 27.6 mg min−1 was noted as optimum for the degradation of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) [80]. Begum and Gautam reported an optimum ozone dosage of 57 mg min−1 for endosulfan and lindane degradation although a higher ozone dosage slightly increased the endosulfan decomposition [70]. Yet other studies reported a linear increase in removal efficiencies with ozone dosage [81]. The above discussion clearly indicates that ozone dosage needs to be optimized in an ozonation process and that a number of experimental factors could influence the removal rate.

Though the ozonation process is effective for treating some organic compounds, a key problem is the accumulation of refractory compounds which interfere with the mineralization of the organic matter present in water. Some compounds were even found to be refractory to the ozonation process [15, 82, 83]. To improve its efficiency, ozonation was therefore combined with other oxidants. The combination of single oxidants can offer very effective treatment by producing more hydroxyl radicals.

| Reference | AOPs applied | Pollutant(s) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | O3, UV/H2O2, O3/H2O2, O3/AC | Diethyl phthalate (DEP) in ultrapure water, surface water, and wastewater | The O3/AC process was the most efficient for the removal of DEP in all three types of water. The O3/H2O2 and O3/AC processes are more efficient than ozonation alone. |

| [26] | O3, UV photolysis, O3/UV, H2O2/O3, O3/H2O2/UV | 1,4-Dioxane | The O3/H2O2/UV process was most efficient for 1,4-dioxane removal at pH 10, with H2O2 : O3 ratio of 0.5. |

| [27] | O3, O3/H2O2, UV/H2O2, UV/O3 UV/H2O2/O3 | Phenol | The UV/H2O2/O3 process at pH 7 with H2O2 = 10 mM was most ecoeffective with 100% of phenol removal within 30 min and 58.0% TOC removal after 1 h. UV/H2O2/O3 was the most effective process for phenol wastewater mineralization. |

| [28] | O3, O3/H2O2, UV/H2O2 | Twenty-four micropollutants including endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals, and personal care products | The general trend of ozone and hydroxyl radical reactivity with the selected micropollutants was explained. Suitable technology for the removal of these micropollutants was suggested based on the micropollutant reactivity with ozone and hydroxyl radical. |

| [29] | O3, UV photolysis, O3/UV, O3/catalyst, UV/catalyst, O3/UV/catalyst, H2O2/UV, H2O2/UV/catalyst | Pyruvic acid | The UV/H2O2 process with or without perovskite catalysts facilitates pyruvic acid removal fastest. The O3/UV/perovskite process was efficient for mineralization. |

| [30] |

|

p-Chlorophenol | Operating conditions such as initial pH, concentration of H2O2, and ferrous salt were optimized for each process. The UV/Fenton and UV/H2O2/O3 processes were found to be the most effective for the degradation and mineralization of p-CP. |

| [31] | O3, H2O2/O3, UV/Fe2+/H2O2 |

|

Ozonation and/or Fenton’s reagent were found to be efficient for TNT degradation. The O3/H2O2 process at pH > 7 was most efficient for 2-MNT and 2.4-DNT removal. |

| [32] | O3/UV, H2O2/UV, O3/H2O2, O3/H2O2/UV |

|

The O3/UV process was the most efficient of the six degradation methods for DCAA and TCAA in water. Decomposition by AOPs was easier for DCAA than for TCAA. |

| [33] | O3, O3/UV, O3/H2O2, UV/H2O2, O3/UV/H2O2 | O-Nitrotoluene | The optimum H2O2 dosage and solution pH were studied. Adding H2O2 to the ozonation process accelerated the oxidation of O-nitrotoluene by a factor of 8. The O3/UV and UV/H2O2 processes are 20 and 10 times more efficient than the ozonation process, respectively. |

| [34] |

|

|

AOP efficiencies are in the following order: adsorption < TiO2 + UV-vis < UV-vis < O3 + TiO2 ≈ O3 < O3 + UV-vis ≈ O3 + UV-vis + TiO2. The O3 + UV-vis and O3 + UV-vis + TiO2 methods are the most economically attractive. |

| [35] | O3, O3/H2O2, O3/activated carbon | Acid Blue 92 (AB92) | Ozone treatment was a very effective method for complete removal of colour but in COD removal it was not efficient. The removal of COD in ozonation, O3/H2O2, and O3/AC processes, 30%, 80% and 100%, respectively. |

| [36] | O3 or O3/H2O2, O3/powdered activated carbon (PAC) | Sodium Dodecylbenzenesulfonate(SDBS) | Comparison of the O3/PAC system with the O3 and O3/H2O2 processes showed that the O3/PAC system was more effective in the removal of SDBS. |

| [37] | O3, O3/UV, UV/H2O2 | Dye house effluent | The AOP efficiency is dependent on the pH and dosage of H2O2. The UV/H2O2 process is 50 times more efficient than the O3/H2O2 process. |

| [38] | Ozonation, sonication, UV photolysis, O3/ultrasound, UV/ultrasound, O3/UV/ultrasound | Phenol |

|

| [39] |

|

Acid Orange 7 | The UV/O3 process was more effective at all times than the US and/or O3 process. The O3/US/UV process was the most efficient for colour and aromatic removal and AO7 dye mineralization. |

The presence of transition metal ions such as Mn2+, Co2+, Ag+, and Fe2+ in the ozonation process has significant catalytic effects in producing hydroxyl radical [92, 93]. Abd El-Raady and Nakajima studied the degradation of formic, oxalic, and maleic acids in the presence of first row transition metal ions such as Co2+, Ni2+, Mn2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cr3+, and Fe2+ and compared the process efficiency with the O3 and O3/H2O2 processes [93]. They concluded that the presence of Co2+ and Mn2+ ions has the highest catalytic activity for the decomposition of oxalic acid and that O3/Co2+ and O3/Mn2+ are more efficient than the O3/H2O2 process. Similarly, Cortes et al. reported that the O3/Mn2+ and O3/Fe2+ processes were more effective in the removal of organochloride compounds than the O3/Fe3+ and O3/high pH systems [92]. Beltrán et al. found that the presence of Co2+ in water significantly enhances the ozonation rate of oxalic acid at acidic pH and that catalytic ozonation proceeds through the formation of a Co(HC2O4)2 complex [94]. Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation has received increasing attention due to its potentially higher effectiveness in the degradation of recalcitrant pollutants [95–101].

3. Fenton and Photo-Fenton Based AOPs

3.1. Fenton Reaction

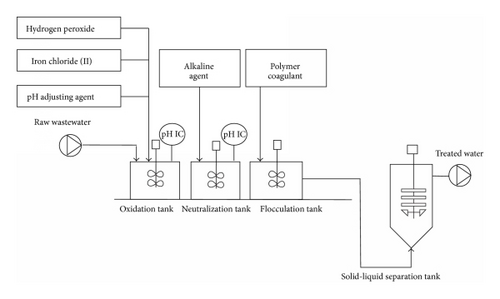

Generally speaking, Fenton’s oxidation process is composed of four stages including pH adjustment, oxidation reaction, neutralization and coagulation, and precipitation. The organic substances are removed at two stages of oxidation and coagulation [106, 107]. •OH radicals are responsible for oxidation, and coagulation is ascribed to the formation of ferric hydroxo complexes [107, 108]. The relative importance of oxidation and coagulation depends primarily on the H2O2/Fe2+ ratio. Chemical coagulation predominates at a lower H2O2/Fe2+ ratio, whereas chemical oxidation is dominant at higher H2O2/Fe2+ ratios [107, 109]. Wang et al. [110] and Lau et al. [111] reported that, in Fenton treatment of biologically stabilized leachate, oxidation and coagulation were responsible for approximately 20% and 80% of overall COD, removal respectively. Fenton oxidation has been tested with a variety of synthetic wastewaters containing a diversity of target compounds, such as phenols [112–114], chlorophenols [115], formaldehyde [116], 2,4-dinitrophenol [116], 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene [117], 2,4-dinitrotoluene, chlorobenzene, tetrachloroethylene [118], halomethanes, amines, and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) [119]. Many chemicals are refractory to Fenton oxidation, however, such as acetic acid, acetone, carbon tetrachloride, methylene chloride, oxalic acid, maleic acid, malonic acid, n-paraffins, and trichloroethane [116]. It has been demonstrated that these compounds are resistant under the usual mild operating conditions of Fenton oxidation [114, 120, 121]. In addition to these basic studies, the process has been applied to industrial wastewaters (such as chemical, pharmaceutical, textile, paper pulp, cosmetic, and cork processing wastewaters), sludge, and contaminated soils [122] resulting in significant reductions of toxicity, improvement of biodegradability, and colour and odour removal [116].

The oxidation rate was influenced by many factors such as pH value, Fe2+ : H2O2 ratio, and the amount of iron salt. Some of these parameters are discussed in detail in the following sections. The Fenton process seems to be the best compromise because it is technologically simple, there is no mass transfer limitation (homogeneous nature), and both iron and hydrogen peroxide are cheap and nontoxic. From the economic point of view, using the Fenton process as a pretreatment can lower the cost and improve biological treatment efficiency [107].

A batch Fenton reactor essentially consists of a pressurized stirred reactor with metering pumps for the addition of acid, a base, a ferrous sulphate catalyst solution and industrial strength (35–50%) hydrogen peroxide. It is recommended that the reactor vessel be coated with an acid resistant material, because Fenton’s reagent is very aggressive and corrosion can be a serious problem. The pH of the solution must be adjusted to maintain the stability of the catalyst, as at pH 6 iron hydroxide is usually formed. For many chemicals the ideal pH for the Fenton reaction is between 3 and 4, and the optimum catalyst to peroxide ratio is usually 1 : 5 wt/wt. Reactants are added in the following sequence: wastewater followed by dilute sulphuric acid catalyst in acidic solutions, base or acid for the adjustment of pH at a constant value, and lastly hydrogen peroxide (which must be added slowly, maintaining a steady temperature). Since wastewater compositions are highly changeable, there are some design considerations to enable the Fenton reactor to operate within flexible parameters. The discharge from the Fenton reactor is fed into a neutralizing tank to adjust the pH of the stream, followed by a flocculation tank and a solid-liquid separation tank for adjusting the TDS (total dissolved solids) content of the effluent stream. A schematic representation of the Fenton oxidation treatment is shown in Figure 2 [123].

As mentioned above, Fenton oxidation was applied to wastewater treatment based on the following observed optimum pH conditions, since this has been shown to affect the degradation of pollutants significantly [106, 124, 125]. The best value pH has been observed to be 2.8–3 in the majority of cases; [116, 126, 127], hence this is the recommended operating pH. At lower pH (pH = 2.5), the formation of (Fe(II) (H2O))2+ occurs, which reacts more slowly with hydrogen peroxide, producing a smaller amount of reactive hydroxyl radicals by reducing the degradation efficiency [123].

Furthermore, the scavenging effect of hydroxyl radicals by hydrogen ions becomes important at a very low pH, at which the reaction of Fe3+ with hydrogen peroxide is also inhibited. At an operating pH of >3, the decomposition rate decreases because of the decreased free iron species in the solution, probably due to the formation of Fe(II) complexes with the buffer inhibiting the formation of free radicals. At a pH higher than 3, Fe3+ starts precipitating as ferric oxyhydroxides and breaks down the H2O2 into O2 and H2O [124, 128], inhibiting the generation of ferrous ions. Additionally, the oxidation potential of •OH radical is known to decrease with an increase in pH [123].

Usually the rate of degradation increases with an increased concentration of ferrous ions [125], though the increase is sometimes observed to be marginal above a certain concentration [106, 129]. Additionally, an enormous increase in ferrous ions will lead to an increased unutilized quantity of iron salts, contributing to increased TDS content in the effluent treatment, which is not permitted. Thus laboratory scale studies are required to establish the optimum loading of ferrous ions under similar conditions, unless data are available in the open access literature [123].

The concentration of hydrogen peroxide plays a more crucial role in the overall efficacy of the degradation process. Usually it has been observed that the percentage degradation of the pollutant increases with an increased dosage of hydrogen peroxide [106, 129]. Care should be taken however in selecting the operating oxidant dosage. The residual hydrogen peroxide contributes to COD, so an excess amount is not recommended. The presence of hydrogen peroxide is also harmful to many microorganisms and affects the overall degradation efficiency significantly where Fenton oxidation is used as a pretreatment to biological oxidation. One more negative effect of hydrogen peroxide, if present in large quantities, is that it acts as a scavenger for the generated hydroxyl radicals. Thus hydrogen peroxide loading should be adjusted so that the entire amount is utilized. This can be decided based on laboratory scale studies with the effluent in question [123].

It should be noted that the dose of H2O2 and the concentration of Fe2+ are two relevant and closely related factors affecting the Fenton process. The H2O2 dose has to be fixed according to the initial pollutant concentration. An amount of H2O2 corresponding to the theoretical stoichiometric H2O2 to chemical oxygen demand (COD) ratio is frequently used [116], although it depends on the response of the specific contaminants to oxidation and on the objective pursued in terms of reducing the contaminant load. Usually a lower initial pollutant concentration is favoured [125], but the negative effects of treating a large quantity of effluent need to be analyzed before the dilution ratio can be set. For real industrial wastes, some dilution is often essential before any degradation is observed using Fenton oxidation [123].

As noted above, as the maximum degradation rates are observed at a pH of approximately 3, the operating pH should be maintained constant around this optimum value. The type of buffer solution used also affects the degradation process [125]. Acetic acid/acetate buffer provides maximum oxidation efficiency, at least as observed for phosphate and sulphate buffers. This can be attributed to the formation of stable Fe3+ complexes under these conditions [123].

Not many studies are available depicting the effect of temperature on degradation rates and ambient conditions can safely be used with good efficiency [123]. Besides, reaction temperature is another crucial parameter in the Fenton process. In principle, increasing the temperature should enhance the kinetics of the process, but it also favours the decomposition of H2O2 towards O2 and H2O. This increases at a rate of around 2.2 times each 10°C in the range of 20–100°C [130]. Oxidation with Fenton’s reagent has already been proved effective and promising for the destruction of several compounds and consequently for the treatment of a wide range of wastewaters, as described in several reviews (e.g. [102, 104, 116, 123, 131, 132]). Table 3 summarizes recent Fenton processes for some wastewater treatments.

| Reference | Process conditions | Pollutant(s) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | A temperature controllable magnetic stirrer ensures perfect mixing at a constant rate of 300 rpm during all experiments. The effect of Fe2+ concentration on COD removal varied in the range of 0.5–10 mM (these factors were kept constant: H2O2 = 30 mM; pH = 3; t = 30 min; COD = 2741 mg/L). The selected H2O2 concentration was in the range of 10–100 mM while pH = 3 and Fe2+ = 10 mM at 30 min. The tested pH values ranged between 2 and 5. | Synthetic acid dye baths (SADB) consist of three different acid dyestuffs (C.I. Acid Yellow 242, C.I. Acid Red 360, and C.I. Acid Blue 264) and two dye auxiliaries (a levelling agent and an acid donor) | Optimum experimental conditions for the simulated acid dye bath effluent were established as follows: Fe2+ = 10 mM, H2O2 = 30 mM, and pH = 3 at room temperature (T = 20°C), which yielded an overall COD removal efficiency of 23%. The corresponding colour removal efficiency was 92% and the first-order COD abatement rate constant increased from 0.02 min−1 to 0.03 min−1 by increasing the temperature from 20 to 50°C. The first-order reaction rate constant for H2O2 consumption increased from 0.15 min−1 to 0.34 min−1 by increasing the temperature from 20 to 50°C. Further increases in temperature did not improve oxidation and oxidant consumption rates. H2O2 consumption ran parallel to COD removal at a rate approximately 10 times faster than COD abatement. |

| [41] | The Fenton reactor was stirred at room temperature in an open-batch system with a magnetic stirring bar and was treated for 2 h. The Fe+2 : H2O2 ratio was varied in the range of 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20, 1 : 30, 1 : 40, and 1 : 50, pH in the range of 2–4, and Fe2+ in the range 0.5 and 1 mM. |

|

The Fenton process was decolourized more than 90% in all cases. The best mineralization extent, that is, maximal TOC removal, 72.1%, was obtained for degradation of RB49 by Fenton process, Fe2+ : H2O2 = 1 : 20, Fe2+ = 0.5 mM at pH = 3. The molecular structure of the dyes studied plays a significant role in oxidation by Fenton type processes. |

| [42] | The oxidation studies were conducted in brown 500 mL glass bottles. The pH of wastewater and bleach was first adjusted to 3 with H2SO4. Degradation of EDTA in distilled water was conducted by Fenton’s reagent with Fe concentrations 0–0.9 mM and a maximum reaction time of 15 min. The temperature reaction and pH were fixed at 60°C and 3, respectively. | Ethylenediamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), novel complexing agents, namely, BCA5 and BCA6 | Fenton’s process proved highly effective in the degradation of EDTA in spiked integrated wastewater. With an initial molar ratio of 70 : 1 (H2O2 and EDTA) or higher, EDTA degradation was nearly complete within 3 min of reaction time. Lower EDTA degradation levels at pH 4 and low temperature in bleaching effluent are a major drawback in this study. |

| [43] | The initial concentrations of Fe(II) used in this study were 8.37, 13.95, 19.53, 25.11, and 33.40 mg/L, the Fe2+ : H2O2 ratios were set at 0.016, 0.028, 0.039, 0.05, and 0.067, and the concentration of H2O2 was kept constant at 500 mg/L. The initial concentrations of H2O2 used in this study were 50, 100, 200, 500, and 700 mg/L, the Fe2+ : H2O2 ratios were set at 0.0199, 0.0279, 0.06975, 0.1395, and 0.279, and the concentration of Fe(II) was fixed at 13.95 mg/L. | Azo dye C.I. Acid Yellow 23 (AY 23) | The decolourization rate is strongly dependent on the initial concentrations of Fe2+ and H2O2. The optimum operational conditions were obtained at pH 3. The results show that as much as 98% of AY 23 can be decolourized by 13.95 mg/L ferrous ions and 500 mg/L H2O2. |

| [44] | All tests were conducted in a 200 mL double glass cylindrical jacketed reactor, which allows cycle water to maintain the reaction mixture at a constant temperature. Temperature control was realized through a thermostat and a magnetic stirrer was used to stir reaction solutions. Operating pH was in the range of 2.5–6.0 and decolouration time was 60 min. Hydrogen peroxide in the range of 1.0 × 10−3 to 4.0 × 10−2 M and the Fe2+ dosage on the decolourization of OG with different initial concentrations from 5.0 × 10−6 to 3.5 × 10−5 M. Reaction temperature was varied in the range of 20–50°C. The effect of the presence of chloride ion (2.82 × 10−2 to 2.82 × 10−1 M) on the decolourization of OG was investigated. The decolourization of different concentrations of OG was studied in the range of 2.21 × 10−5 to 1.66 × 10−4 M. | Azo dye Orange G (OG) | The results showed a suitable decolourization condition of initial pH 4.0, H2O2 dosage 1.0 × 10−2 M, and molar ratio of [H2O2]/[Fe2+] 286 : 1. The decolourization efficiencies within 60 min were more than 94.6%. It was found that the decolourization efficiency of OG enhanced with increased reaction temperature but the presence of chloride ion had a negative impact on the decolourization of OG. The decolourization kinetics of OG by Fenton oxidation process followed the second-order reaction kinetics, and the apparent activation energy E was detected to be 34.84 kJ/mol. |

| [45] | Chemical oxidation of the red dye solutions with Fenton’s reagent was carried out in a closed jacketed batch reactor (1 L capacity). The reactor was provided with constant stirring, accomplished through a magnetic bar and a Falc magnetic stirrer. The temperature of the reaction mixture was kept constant by coupling the reactor to a Huber thermostatic bath. Operating pH and H2O2 concentration were varied in the range of 2–5 and 5.9–8.8 mM, respectively. The effect of the Fe2+ concentration and reaction temperature was investigated in the range of 0.13–1.1 mM and 20–70°C, respectively. | Azo dye (Procion Deep Red H-EXL gran) | Total organic carbon (TOC) reduction occurred after 120 min of reaction; however, the reaction time required to achieve colour removal levels above 95% is around 15 min. Four operating variables must be considered, namely, the pH, the concentration of hydrogen peroxide, the temperature, and the concentration of ferrous ion, between 3-4, 5.9 mM, 20 min, and 0.27 mM, respectively. It was concluded that temperature and ferrous ion concentration are the only-variables that affect TOC removal, and, due to cross interactions, the effect of each variable depends on the value of the other one, thus affecting the process response positively or negatively. |

| [46] | Fenton’s reagent experiments were carried out at room temperature (23 ± 2°C) using different H2O2 and Fe(II) doses at pH 3.5. The percentage variation of simazine removal was investigated with H2O2 concentration at different simazine doses between 0.5 and 5.0 mg/L and at different Fe(II) doses between 5 and 30 mg/L at the end of a 6 min reaction time. | Simazine | At a constant simazine concentration, the percentage of TOC removal increased with increasing H2O2 and Fe(II) concentrations up to 15 mg/L Fe(II) and 50 mg/L peroxide above which mineralization decreased due to the scavenging effects of H2O2 on hydroxyl radicals. Maximum pesticide (100%) and TOC removals (32%) were obtained with H2O2/Fe(II)/simazine ratio of 55 : 15 : 3 (mg/L). Simazine degradation was incomplete, yielding the formation of intermediates which were not completely mineralized to CO2 and H2O. |

| [47] | The experiments were performed in an insulated vessel with a capacity of 1 L mounted on a steel frame and stirred at 130 rpm. The pH of initial solutions was set at 3. Gradation efficiencies were compared by varying Fenton’s reagent concentration and ratios. The parallel monitoring of Fenton’s reagent concentrations allowed the evidencing hydrogen peroxide or ferrous ion contents as limiting factors for TNT removal. The [H2O2]0/[Fe(II)]0 ratio was varied in the range of 0.1–2 mM. | TNT | Fenton oxidation is an effective method to transform TNT totally in contaminated aqueous solution. This is feasible by the efficient generation of hydroxyl radicals during H2O2 catalytic decomposition with Fe(II) ions. TNT degradation kinetics and efficiency are largely influenced by H2O2 and Fe2+ concentrations. Using [H2O2]0 : [Fe(II)]0 molar ratios equal to or lower than 0.5 leads to the formation of the maximum number of intermediates. The absolute rate constant of the reaction between hydroxyl radicals and TNT is 9.6–10 × 108 M−1 s−1. |

| [48] | The Fenton reactor was a 0.5 L beaker placed in a thermostat water bath with constant temperature and stirred by a magnetic stirrer, with operating pH values of 2.50, 3.00, 3.50, 4.00, and 5.00, initial H2O2 concentration in the range of 0.10 mM to 4.00 mM, initial concentration of Fe2+ from 0.01 mM to 0.10 mM, and initial Amido Black 10B concentration on its degradation in the range of 10–100 mg/L. A series of experiments were conducted by varying the temperature from 15°C to 45°C. | Azo dye Amido Black 10B | The optimal operation parameters for the Fenton oxidation of Amido Black 10B were 0.50 mM [H2O2]0 and 0.025 mM [Fe2+]0 for 50 mg/L [dye]0 at an initial pH of 3.50 at a temperature of 25°C. Under these conditions, 99.25% dye degradation efficiency in aqueous solution was achieved after 60 min of reaction. The Fenton treatment process showed that it was easier to destruct the –N = N-group than to destruct the aromatic rings of Amido Black 10B. |

| [49] | Fenton oxidation was performed in a batch reactor under initially anaerobic conditions to determine the effect of [MTBE]0 on the degradation of MTBE with FR: MTBE degradation at different [MTBE]0 in the range of 1, 2, and 5 mg/L when treated with the same amount of FR. This study was performed using solutions containing [MTBE]0 of 11.4 and 22.7 mM, each one in individual experiments at pH values of 3.0, 3.6, 5.0, 6.3, and 7.0. The FR to MTBE molar ratio varied in the range of 0.5 : 1 and 200 : 1. The initial concentration of pollutant was 22.7 μM and FR was used in a 1 : 1 molar ratio of ferrous iron (Fe2+) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at pH = 3. | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | FR partially degraded low [MTBE]0 in water (11.4 and 22.7 μM). Experiments at acidic pH yielded the best results of MTBE degradation (>90%), and small differences were observed between the results at pH 3.0 and 5.0. The majority of MTBE degradation and generation of intermediates occurred during the initial phase and followed pseudo first-order kinetics. |

| [50] | The experiments were conducted in batch mode. 4L borosilicate reactors were filled with 3.6 L of deionized (DI) water at pH = 3.0 and purged with high-purity nitrogen until the dissolved oxygen (DO) reading was below 0.01 mg/L and the oxygen concentration in the head space was negligible (≈ 0.01%). | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | The added amount of FR proved to be an important controlling parameter for the overall MTBE degradation mineralization efficiency. An FR to MTBE molar ratio of 20 : 1 was the minimum required to achieve complete MTBE degradation. Kinetic analysis is reported to be pseudo first-order given the good linear correlation found between k′ and FMMR. Other intermediates not identified in this study are generated in significant concentrations at these conditions. |

| [51] | A series of experiments were conducted at pH 3 for 5, 15, or 60 min of mixing followed by 30 min clarification. The studied H2O2/Fe2+ stoichiometric molar ratios were 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10 with H2O2 dose of 1000 mgL−1, and the H2O2/Fe2+ stoichiometric molar ratios were 0.5, 2, 3, 5, and 10 with H2O2 dose of 500 mgL−1. A further series of experiments were conducted at an initial pH of 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7 with 5 min mixing followed by 30 min clarification. Comparisons between the Fenton process and Fe3+ coagulation were carried out at an initial pH of 3 and 7. | Nuclear laundry water | The experimental data generally indicated decreased removal efficiencies of organic compounds with an increasing H2O2/Fe2+ ratio. Yet taking into account all factors, thermostat cost-effective degradation conditions were at H2O2/Fe2+ stoichiometric molar ratio of 2 with 5 min mixing and an H2O2 dose of 1000 mgL−1. The initial pH of the laundry water can be as high as 7. Fe3+ coagulation experiments were conducted in order to interpret the nature of the Fenton process. Since the removal efficiency of organic compounds in the Fenton process was slightly higher than in coagulation, the treatment of the nuclear laundry water can be called Fenton-based Fe3+ coagulation. |

3.2. Photo-Fenton Processes

The photo-Fenton process, as its name suggests, is rather similar to the Fenton one but also employs radiation [102, 104, 123, 133]. The photo-Fenton reaction is also well known in the literature [104, 134] as an efficient and inexpensive method of wastewater and soil treatment [104, 135]. Photo-Fenton process is known to be capable of improving the efficiency of dark Fenton or Fenton-like reagents by means of the interaction of radiation (UV or Vis) with Fenton’s reagent [136]. This technique has been suggested as feasible and promising for removing pollutants from natural and industrial waters and increasing the biodegradability of chlorophenols when used as a pretreatment method to decrease water toxicity [104]. Some of its most innovative applications include oxalate as a ligand of iron ions [104, 137].

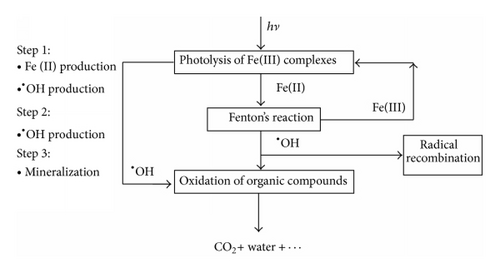

Since Reaction (30) occurs instead of Reaction (27), organic pollutants are mineralized even without irradiation. It should be noted, however, that Reaction (30) is rather slower than Reaction (27). Thus the degradation rate under dark conditions is rather lower than that of the photo-Fenton reaction [136]. Figure 3 shows the reaction pathways for the process starting with the primary photoreduction of the dissolved Fe(III) complexes to Fe(II) ions followed by Fenton’s reaction and the subsequent oxidation of organic compounds. Additional hydroxyl radicals generated in the first step also take part in the oxidation reaction [140].

Appropriate implementation of the photo-Fenton treatment depends mainly on the operating variables—H2O2/COD molar ratio, H2O2/Fe2+ molar ratio, and irradiation time. The conventional method is to optimize the operating variables by changing one factor at a time; that is, a single factor is varied while all other factors are kept unchanged for a particular set of experiments. Likewise, other variables are individually optimized through single-dimensional searches, which are time consuming and incapable of reaching the actual optimum as interaction among variables is not taken into consideration [141]. Some illustrative works from recent years are discussed in detail in Table 4.

| Reference | Process conditions | Pollutant(s) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [52] | Natural pH conditions with phenol concentrations in the range of 180–733 mg/L. The photochemical treatment was mediated with ferrioxalate and peroxide in two photoreactors of different volumes and operation conditions (batch and with closed flow). | Wastewater | Phenol transformation efficiencies of 100% and total COD reduction percentages of 85% were reached within the first hour of phototreatment, with an aromatic free effluent as the final product in both types of reactor. The ferrioxalate type complexes using mass ratios of oxalate/phenol = 1.5, oxalate/Fe3+ = 15, and H2O2/phenol > 5.0 were shown to be very effective in the treatment of these effluents, even at pH conditions close to neutral, the pH region in which Fenton type processes begin to lose efficiency due to the precipitation of iron as a hydroxide. |

| [53] | Photo-Fenton process in a CPC solar photoreactor. The effect of solar activated photo-Fenton reagent at pH 5.0 before and after a slow sand filtration (SSF) process in waters containing natural iron species was investigated. | Natural organic matter (NOM) model compounds (dihydroxy-benzene) | The results showed that the total transformation of dihydroxybenzene compounds was obtained with a mineralization of over 80%. The mineralization of organic compounds dissolved in natural water was higher than in Milli-Q water, suggesting that the aqueous organic and inorganic components (metals, humic acids, and photoactive species) positively affect the photocatalytic process. When 1.0 mg/L of Fe3+ was added to the system, photo-Fenton degradation improved. |

| [54] | Two laboratory scale photo-Fenton experiments were performed with the solar simulator and SMX dissolved in diluted water (DW) and in seawater (SW) at the same concentration (50 mg/L; DOC = 23.75 mg/L) as in the pilot plant experiments for their comparison with natural solar radiation. The initial DOC of SW was 2.6 mg C/L. The experiments were performed at three different initial concentrations of FeSO4·7H2O (2.6, 5.2, and 10.4 mg/L). Initial H2O2 concentrations ranged from 30 to 210 mg/L. The solar pilot plant reactor consisted of a compound parabolic collector (CPC) with a 3.0 m2 irradiated surface and total volume of 39 L. | Antibiotic sulfamethoxazole (SMX) | The photo-Fenton degradation of SMX was strongly influenced by the seawater matrix when compared to distilled water. Indeed, in seawater it is proposed that degradation occurs mainly through and Cl1− (or ) and not through HO−. The increased iron concentration showed a slight improvement on the pollutant degradation and mineralization rate. The increase of H2O2 concentration up to 120 mg/L in distilled water reduced the sample toxicity during the photo-Fenton process, which demonstrates that this is a feasible technology for the treatment of wastewater containing this compound. |

| [55] | Photo-Fenton oxidation was carried out using a cylindrical Pyrex thermostatic cell with a 300 mL capacity (T = 23 ± 1°C), equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The dye solution volume was 250 mL. A 6 W Philips black light fluorescent lamp which basically emits at 350 nm was used as an artificial light source. The incident light intensity, measured with a uranyl actinometer, was 1.38 × 10−9 Einstein s−1. A few Fenton reagent doses were tested in the present work (a series of three experiments): 5 mg/L Fe(II) and 125 mg/L H2O2, 10 mg/L Fe(II) and 125 mg/L H2O2 10 mg/L Fe(II) and 250 mg/L H2O2. Contaminants with a ratio of BOD5/COD ≥ 0.4 are generally accepted as biodegradable, while those with ratios between 0.2 and 0.3 units were partially biodegradable. | Homo-bireactive dye (Procion Red H-E7 B) | The results demonstrated that a photo-Fenton reaction can be used successfully as a pretreatment process to biocompatibilize Procion Red H-E7B reactive dye solutions. The best pretreatment results were obtained with 60 min of photo-Fenton irradiation time and 10 mg/L Fe(II) and 125 mg/L H2O2 of initial reagent concentration. Under these conditions, the BOD5/COD index increased from 0.10 to 0.35 units with 39% mineralization and 16.5 mg/L of residual H2O2. The use of photo-Fenton type reactions as a pretreatment allows the SBR system to remove Procion Red H-E7B Reactive Dye from aqueous solution, which improves the low success rate of aerobic biological removal of dye colour. |

| [56] | This study explored the application of the solar photoFenton process to the degradation of PNA in water. The operating pH value was varied in the range of 3–6. The effect, of H2O2 and Fe2+ dosage on the degradation of PNA by solar photo-Fenton process were investigated between 2.5–40 and 0.025–0.1 mM, respectively. Also the effect, of temperature and initial pollutant concentration were investigated in the range of 20–50°C and 72 × 10−3–217 × 10−3 mM. | P-Nitroaniline (PNA) | The optimum conditions for the degradation of PNA in water were considered to be pH 3.0, 10 mmol/L H2O2, 0.05 mmol/L Fe2+, 0.072–0.217 mmol/L PNA, and temperature 20°C. Under optimum conditions, the degradation efficiencies of PNA were more than 98% within a 30 min reaction time. The degradation characteristic of PNA showed that the conjugated systems of the aromatic ring in the PNA molecules were effectively destroyed. The experimental results indicated that the solar photo-Fenton process has advantages over the classic Fenton process, such as higher oxidation power, a wider working pH range, and a lower ferrous ion usage. |

| [57] | During the experiment, H2O2 was added continuously to the reactor at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with a syringe pump. Two 8 W monochromatic UV lamps of 312 nm (with an emission range between 280 and 360 nm) were placed axially in the reactor and kept in place with a quartz sleeve. The UV intensity of one 8 W UV lamp is 60 μW/cm. The reaction temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1°C using a water bath. A two factor CCD was carried out using H2O2 dosage rate ranging from 1 to 10 mg/L min and Fe3+ dosage from 1 to 100 mg/L to investigate their influence on carbofuran degradation under the photo-Fenton process. | Carbofuran | Under these conditions, the toxicity unit measured by Microtox test with 5 min exposure was decreased from 47 to 6 and the biodegradability evaluated by BOD 5/COD ratio was increased from 0 to 0.76 after a 60 min reaction. The results obtained in this study demonstrate that the photo-Fenton process is a promising pretreatment to biological treatment for carbofuran removal from contaminated water or wastewater. |

| [58] | Experiments were carried out in a Pyrex glass cylindrical reactor of 0.10 m diameter and 0.20 m height. The working volume was 1 L and all experiments were conducted in batch mode. The initial solution pH was adjusted to 3 which is the optimal value for the Fenton and photo-Fenton reactions using sulphuric acid. All experiments except those in the dark and at night were carried out between 10 am and 4 pm. The mean solar radiation during the experiments from October to January was in the range of 2.55–3.01 kWh (m2 day)−1. The effects of solar light, initial Fe concentration, and initial H2O2 concentration were investigated. | Acid Orange 7 | With increasing Fe dosage the decolourization rate increased, but the enhancement was not pronounced beyond 10 mg/L. Although the addition of H2O2 increased the decolourization rate up to around 1000 mg/L of H2O2, further additions of H2O2 did not enhance colour removal. At excess dosages of Fenton reagents, colour removal was not improved, due to their scavenging of hydroxyl radicals. It was found that the pseudo first-order decolourization kinetic constant based on the accumulated solar energy is the sole parameter unifying solar photo-Fenton decolourization processes under different weather conditions. |

4. UV/H2O2 Process

-

Initiation (Rate Constant)

()() -

Propagation [144] (Rate Constant)

()()() -

Termination [144] (Rate Constant)

()()

Tubular reactor configurations are usually employed for direct photolysis and photo-Fenton processes or processes based on H2O2/UV reagent, in order to achieve a good interaction between CPs, other intermediates, and radiation [104, 149]. Also various lamps are employed to generate the radiation supplied to CP samples for direct UV photolysis and for techniques based on UV/H2O2, UV/O3, photo-Fenton processes, and photocatalysis. The various commercial radiation sources employed include high, medium, and low pressure mercury vapour lamps for the generation of UV radiation [149–151] and solar-simulated xenon lamps as a source of visible radiation [152]. The lamp can be located either in an axial position housed by a sleeve [150] or vertically, in its centre [104]. The typical findings observed in the UV/H2O2 process are listed in Table 5.

| Reference | Process conditions | Pollutant(s) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [59] | For photolytic experiments, the samples were irradiated with a UV lamp with an output of 254 nm operating at 50–60 Hz with a current intensity of 0.12 A at ambient temperature. The photolytic decolouration of carmine via UV radiation in the presence of H2O2 was optimized using response surface methodology (RSM) utilizing Design-Expert 7.1. |

|

Under the optimized conditions of 62 μM dye, 5.5 mM H2O2, and pH 4, the experimental values were as predicted, indicating the suitability of the model and the success of RSM in optimizing photooxidation conditions for carmine dye. In the optimization, R2 and correlation coefficients for the quadratic model were evaluated quite satisfactorily at 0.998 and 0.997, respectively. |

| [60] | UV/TiO2/H2O2, UV/TiO2, and UV/H2O2 were compared as pretreatment processes to detoxification and treatment. The tubes were then irradiated for 40 h (initial concentrations of 50 mg/L) or 56 h (initial concentrations of 100 mg/L) at 300 μW cm−2 with two 18 W UV bluelamps and an initial chlorophenol concentration of 50 mg/L. |

|

Chlorophenol photodegradation was well described by a first-order model kinetic (r2 > 0.94) and the shortest 4CP, DCP, TCP, and PCP half-lives were achieved during UV/TiO2/H2O2 treatment at 8.7, 7.1, 4.5, and 3.3 h, respectively. |

| [61] | A 60 W mercury vapour lamp (UV C, 253.7 nm) with a frequency of 50 Hz and a voltage of 240 V was used. The initial concentrations of H2O2 and melanoidin were manipulated while pH, flow rate, irradiated surface area, volume, lamp intensity, and temperature were kept constant. The relative change of each constituent was identified at various initial concentrations of H2O2 (up to 12000 mg/L) and melanoidin (263–5314 mg-Pt Co/L). | Melanoidin | UV/H2O2 was shown to remove the colour associated with melanoidin effectively. The process was less effective in removing the DON and DOC present in the melanoidin solution. At the optimum H2O2 dose (3300 mg/L), with an initial melanoidin concentration of 2000 mg/L, the removal of colour, DOC and DON was 99%, 50%, and 25%, respectively. |

| [62] | This study compared the efficacy of UV photodegradation with that of different advanced oxidation processes (O3, UV/H2O2, O3/activated carbon). Photo-irradiations were carried out using a merry-go-round photoreactor (MGRR), DEMA equipped with a 500 WTQ 718 Heraeus medium-pressure mercury lamp (239–334 nm) or a TNN 15/32 Heraeus low-pressure mercury lamp (254 nm). The temperature in the MGRR was kept at 25.0 ± 0.2°C during all irradiations. The concentration of H2O2 used was 3 mM. | Naphthalene sulphonic acids | These results demonstrated that the treatment of naphthalene sulphonic acids with UV radiation is not effective in their removal from aqueous solutions. The presence of duroquinone and 4-carboxybenzophenone during the irradiation of naphthalene sulphonic acids increases their elimination rate. O3/activated carbon and UV/H2O2 based systems were found to be more efficient than the irradiation process in the removal of naphthalene sulphonic acids from aqueous solutions. |

| [63] | The reactor had a 1 L capacity and was equipped with a mercury medium-pressure steam UV lamp which was 110 mm in length and used 1000 W, 145 V, and 7.5 A. In the UV light/H2O2 flow reactor system, the initial concentration of sulphide was 6.34 mg L−1. The initial concentrations of sulphurous water were 6.34 mg L−1 of HS−, 1000 mg L−1 of , and 1.5 mg L−1 of . The amount of hydrogen peroxide added was of 6 × 10−4 mL L−1. | Sulphurous water | In a batch reactor it was possible to demonstrate that the sulphur compounds of the sulphurous waters could be oxidized to sulphate in a UV light/H2O2 air system with very small concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (6 × 10−3 mL L−1). In a flow reactor it was possible to obtain the same results by adding only 6 × 10−4 mL L−1 of hydrogen peroxide. |

| [64] | Radiation energy was supplied by two lamps. Two different types of lamp were used: (1) two Philips TUV lamps with an input power of 15 W each and (2) two Heraeus UV-C lamps operated with an input power of 40 W each. Both types of lamp are low pressure mercury vapour lamps with one single significant emission wavelength at 253.7 nm. DCA concentration and radiation absorbing species concentration (H2O2) were 60 ppm, 145 ppm and pH and temperature were kept at 3.4 and 20°C, respectively. | Dichloroacetic acid (DCA) | The fastest degradation rate was obtained with the H2O2/UV40W system, followed by H2O2/UV15W. Although the photocatalytic process was effective in degrading DCA, the reaction rate was much slower when compared with the homogeneous processes. For the H2O2/UV40W reaction, the DCA conversion at teff = 530 s (ca. 4 h of reaction) is more than 80%, whereas the H2O2/UV15W system reaches half of this value. The DCA and TOC conversion values are similar in each process. This is in agreement with the fact that there are no stable reaction intermediates and DCA is rapidly converted into HCl and CO2. |

| [65] | Low pressure mercury vapour lamps with a maximum emission primarily at 253.7 nm were used as the light source. The changes in the pH of dye solutions as a function of the irradiation time for different initial pH values are carried out. The effect of the initial H2O2 concentration in a range of 10–100 mM on the rate of RO16 decolourization was investigated. The effect of the initial RO16 concentration in a range from 20 to 80 mg dm−3 on the efficiency of dye degradation was also investigated. The influence of UV light intensity on the decolourization of RO16 azo dye was monitored by varying the light intensity from 730 up to 1950 μW cm−2. | Azo dye Reactive Orange 16 | The UV/H2O2 process could be used efficiently for the decolourization of aqueous solutions of the azo dye Reactive Orange 16. It was found that the rate of decolourization is significantly affected by the initial pH, the initial hydrogen peroxide concentration, the initial dye concentration, and the UV light intensity. The decolourization follows pseudo first-order reaction kinetics. Peroxide concentrations in the range from 20 to 40 mM appear to be optimal. Colour removal was observed to be faster in neutral pH solutions than in acidic and basic ones. The hydroxyl radical scavenging effect of the examined inorganic anions increased in the order phosphate < sulphate < nitrate < chloride. |

Ultimate oxidation of CPs to carbon dioxide and water has rarely been obtained under typical test conditions. As summarized in Table 4, typical half-life times are between 0.3 and 20.1 minutes for CP degradation, depending on the initial concentration of CP and hydrogen peroxide, the intensity of radiation, and the degree of chlorination. It is observed that the degradation rates increase when the number of chlorine substituents decreases [104].

5. Conclusion

Recent developments in various homogeneous AOPs have been analysed comprehensively. The principle of individual and combined AOPs and their efficiency on the degradation of various pollutants was discussed. The influence of various experimental parameters such as oxidant dosage, solution pH, flow rates, substrate concentrations, water matrix, and light intensity on the AOPs was explored. This review also listed various AOPs applied for the degradation of contaminants under different experimental conditions. Combined AOPs substantially enhanced the degradation rate by generating more reactive radicals under suitable conditions. The optimum oxidant dosage and solution for efficient removal were reported.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the National Science Council (NSC) in Taiwan for their financial support under the Contract no. NSC-101-2221-035-031-MY3. The Laboratory of Green Chemistry, Mikkeli, Finland, and Water and Environmental Technology (WET) Center, Temple University, are also gratefully acknowledged for their partial financial support of this study.