Could Upregulated Hsp70 Protein Compensate for the Hsp90-Silence-Induced Cell Death in Glioma Cells?

Abstract

The molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 alpha (Hsp90α) has been recognized in various tumours including glioma. This pilot study using a proteomic approach analyses the downstream effects of Hsp90 inhibition using 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17AAG) and a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) oligonucleotide targeting hsp90α (shhsp90α) in the U87-MG glioma cell line. Preliminary data coupled with bioinformatic analysis identified several known and unknown Hsp90 client proteins that demonstrated a change in their protein expression after Hsp90 inhibition, signifying an alteration in the canonical pathways of cell cycle progression, apoptosis, cell invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Members of the glycolysis pathway were upregulated, demonstrating increased dependency on glycolysis for energy source by the treated glioma cells. Upregulated proteins also include Hsp70 and members of its family such as Hsp27 and gp96, thereby suggesting the role of Hsp90 co-chaperones in compensating for Hsp90 function after Hsp90 inhibition. Considering Hsp70’s role in antiapoptosis, it was postulated that a combination therapy involving a multitarget approach could be carried out. Consequently inhibition of both Hsp90 and Hsp70 in U87-MG glioma cells resulted in 60% cell death indicating the importance of combination therapy for glioma therapeutics.

1. Introduction

Heat shock protein Hsp90 is upregulated in several tumours including glioma, and thus targeting its function may provide new therapeutic aspects [1, 2]. Hsp90 is a highly conserved molecular chaperone present in eukaryotic cytosol. It has been proposed to play a vital role in tumorigenesis, maintenance of transformation and regulation of several key proteins involved in apoptosis and survival and growth pathways [3]. These pathways are exploited in tumours where Hsp90 chaperoning contributes towards drug resistance [4], metastasis [5], and cell survival [6]. The synthesis of several natural and chemical inhibitors along with RNA inhibition using siRNA or shRNA to silence Hsp90 has been undertaken.

Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that enhanced chemosensitivity is attained upon transcription inhibition of the inducible Hsp90 subunit hsp90α by siRNA, suggesting that inhibiting hsp90α expression by shRNA could possibly be a favourable therapeutic approach compared to conventional chemotherapies as it is target specific and has reduced toxicity. Furthermore, a combination treatment of siRNA followed by Temozolomide (TMZ) (200–400 µM) after 48 hours was significantly more effective, suggesting the combination as a possible effective form of therapy [7]. Given its functions as a molecular chaperone and its expression in gliomas, hsp90α may represent a promising target for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. This study investigated Hsp90 chaperone inhibition with (a) 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17AAG), an analogue of Geldanamycin (GA) and a potent Hsp90 inhibitor and (b) short hairpin RNA (shRNA) oligonucleotide targeted against hsp90α.

In this study, proteins were extracted from the U87-MG cell lysate to characterize the changes transpired after Hsp90 inhibition with 17AAG and shRNA (hsp90α) using a differential proteomic analysis. Proteins expressed in wild-type U87-MG cells (control) were compared with the proteins expressed in U87-MG cells upon subsequent silencing of hsp90α (U87-MG-shhsp90α) and the proteins expressed in U87-MG cells after 17AAG treatment (U87-MG-17AAG).

This approach elucidates the changes caused in the Hsp90 chaperone system after inhibition using 17AAG or shRNA oligonucleotide targeting hsp90α in glioma. Though the significance of Hsp90’s glioma regulation has been well documented, the downstream effect of Hsp90 inhibition at the various physiological and signalling pathways in glioma is still ambiguous. Silencing hsp90α at the genetic level (shRNA) and at the protein level (17AAG) to identify potential downstream pathways and proteins affected and/or controlled by Hsp90 in glioma is a novel approach. Therefore, this pilot study aims to silence Hsp90 by using 17AAG and shRNA targeting hsp90α and attempts to identify the potential pathways and proteins altered in glioma.

This study also explores the role of Hsp70 as a co-chaperon for Hsp90. Hsp70 is the most predominant and conserved class of the Hsps [8], and it functions as an antiapoptotic protein [9]. It forms a multichaperone complex with Hsp90 and is involved in folding and refolding of newly synthesized or misfolded proteins [9, 10]. Hsp70 with Hsp90 plays vital roles in tumour immunity by preventing apoptosis and regulating the generation of stable complexes with cytoplasmic tumour antigens bestowing antitumour immunity [11, 12]. In tumours, Hsp70 is upregulated and plays a key role in the regulation of several pathways such as cell proliferation, metastasis, invasion, and death [13]. The over expression of Hsp70 has been associated with poor prognosis, and reduced response to tumour therapeutics [14]. Members of the Hsp70 family act at multiple points in the apoptotic pathway and inhibit cell death [15–17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The human brain cell line U87-MG (glioblastoma) used in this study was purchased from European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECCAC, UK). U87-MG was cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) (Sigma, UK) and was supplemented with 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL, UK) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, UK). Cells were cultivated in 25 or 75 cm2 culture-treated polystyrene flasks and were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in filtered air. Cells were closely monitored and when a monolayer growth of 70–80% confluence was obtained, the cells were scraped and subcultured.

2.2. shRNA Transfection

Purified and sequence verified pGFP-V-RS expression plasmids with hsp90α specific shRNA cassettes were obtained from Origene, USA. The sequence of the shRNA verified to silence hsp90α was shRNA (NM_005348; targeted exon 10 at nucleotides 2137–2166 bp) (sense) 5′CTCTCAAGGACTACTGCACCAGA3′ (antisense) 5′GAGAGTTCCTGATGACGTGGTCTTACTTC3′. The shRNA plasmids were diluted with 50 μL of dH2O to get a final concentration of 100 ng/μL, from which 1 μg of the shRNA expression plasmid DNA was then transfected into the cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol using MegaTran 1.0 solution. The cells were then incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator for 48 hours before being used for further analysis.

2.3. 17AAG and KNK437 Treatment

17AAG (InvivoGen, USA) and KNK437 (Merck Bioscience, UK) were solubilised in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, UK). U87-MG cells were treated for 48 hours with inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 17AAG (0.25 μM) and KNK437 (55 nM) (unpublished results) and then with a combination of IC50 values of 17AAG and KNK437. The relative IC50 values were determined using point to point analysis. CellTitre-Glo one solution assay (Promega, UK) was used to determine the percentage of viable cells present in culture. The assay quantifies the level of the present ATP which is indicative of the presence of metabolically active cells. The raw data of the luminescence units were plotted against the different drug(s) concentration used, and regression analysis was used to determine the IC50 of the drug(s).

2.4. Akt/PKB Kinase Activity

The Akt/PKB kinase activity was assayed using a solid-phase enzyme-linked immune-absorbent assay kit (Assay Deigns, UK) that detects the Akt/PKB activity in the solution phase. Proteins were extracted from the control cells (U87-MG Wild-Type) and treated cells (U87-MG-17AAG; U87-MG-shhsp90α) using CelLytic MT mammalian tissue lysis buffer (Sigma, UK). Bradford’s assay was used to determine the protein concentration and, 1 μg of protein from each sample was used to perform the Akt/PKB kinase activity assay following the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5. Flow Cytometry

The control and treated cells (>1 × 106 cells) were collected by scraping. The cells were washed 3 times with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) made in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After each wash, the cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were permeabilised by incubating with 0.1% of 0.1 M Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min in the dark followed by 3 washes with 0.1% BSA. The blocking solution (made up with 5% rabbit serum in 0.1 M PBS) was added to the cells and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were centrifuged and the blocking solution was discarded, and Hsp90α specific primary antibody, (rat monoclonal IgG2a (1 : 50) made up in 5% rabbit serum with 0.1 M PBS) was added and incubated for 30 min. The primary antibody was removed after 3 washes with 0.1% BSA. Hsp90α secondary antibody {rabbit anti-rat IgG conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (1 : 130)} prepared similar to the primary antibody preparation was added to the cell sample and incubated in the dark for 30 min. The negative control was prepared by excluding the labelling with primary antibody. The cells were washed 3 times and resuspended in 0.1% BSA. The cell suspension was filtered to remove clumps using a sterile filter. The samples were stored at 4°C in the dark until being analysed on the flow cytometer. Throughout the experimental process the samples and the reagents were kept on ice to minimize cell death. The samples during each wash were gently pipetted to achieve a single cell suspension.

2.6. Proteomic Analysis

Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) and protein identification (ID) were performed by Applied Biomics, Inc (Hayward, CA). Both the control and treated cell pellets were obtained by scraping, and the culture medium was removed by washing the pellets 3 times with washing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM magnesium acetate, pH 8.0). Also, 200 µL of 2D cell lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 4% CHAPS) was added to 10 mg of cultured cell pellet. The mixture was sonicated at 4°C followed by shaking for 30 min at room temperature and then centrifuged for 30 min at 14000 rpm. The supernatant was collected, and Bio-Rad protein assay method was used to measure the protein concentration.

The protein extracts (~25–50 µg) from the control and treated U87-MG cell samples were subjected to labelling using CyDye DIGE fluors (Cy2, Cy3 or Cy5). Proteins were separated using two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) under denaturing conditions. The gels were stained and scanned using Typhoon TRIO (Amersham BioSciences, US) following protein separation. Differential regulation amidst the proteins was analyzed using Image Quant software (Amersham Bioscience, USA) by merging the images obtained. DeCyder analysis was performed for automated detection, background subtraction, quantitation, normalization, and intergel matching and spot picking. Protein identification was carried out using a mass spectrometer, in particular Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF). The peptide masses derived from the mass spectrometric analysis were matched with peptide fingerprints of known proteins in a protein sequence database using search engine MASCOT 2.0 (Matrix Science, US).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for three independent experiments. Student’s t-test and paired t-test were used to test the difference between the samples. Values of significance between *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

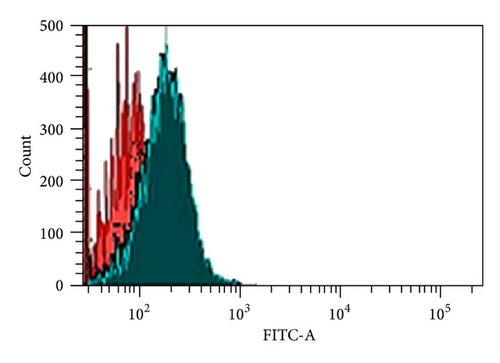

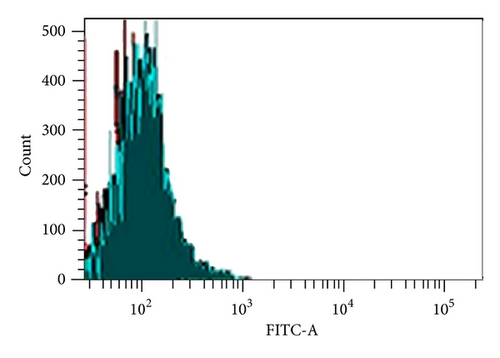

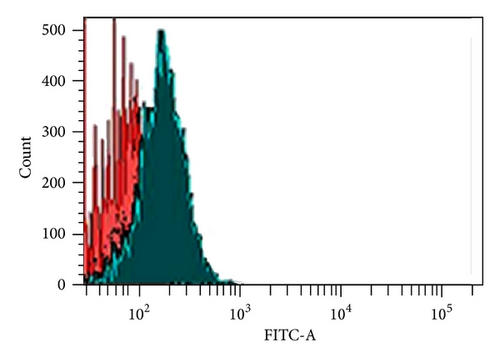

Hsp90α inhibition was initially compared by studying the protein level of Hsp90α in the control (wild-type U87-MG cells) and the treated cells with shhsp90αand 17AAG referred to as U87-MG-shhsp90α and U87-MG-17AAG, respectively, using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis with a flow cytometer (Figure 1 and Table 1). These results demonstrate that both treatments can significantly inhibit the expression of Hsp90α in the U87-MG glioma cell line (**P < 0.001). The results also demonstrate that 17AAG works more effectively than shRNA.

| Samples | Kinase activity for 1 μg Protein | Hsp90α expression [%] |

|---|---|---|

| U87-MG (Control) | 234.51 ± 4 | 76 ± 0.7 |

| U87-MG-17AAG | 44.53 ± 0.1** | 42.7 ± 0.2** |

| U87-MG-shRNA hsp90α | 95.16 ± 1.9** | 64.1 ± 1.4** |

- Data values are mean ± standard deviation, n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 are considered to be statistically significant, with * being significant and ** being very significant.

- Note: Hsp90 protein levels were determined by FACS analysis, and Akt/PKB kinase activities were measured in the control (wild-type U87-MG cells), treated cells (U87-MG-shhsp90α and U87-MG-17AAG), and its activity.

Previous studies suggested the importance of Hsp90 in the maintenance of AKT kinase activity [18]; thus correlating the Hsp90 client protein Akt/PKB kinase activity levels is indicative to the activity of Hsp90, determined using the Akt/PKB kinase activity assay kit.

Akt/PKB kinase activity assay kit was used to measure the activity of Akt/PKB kinase in the control (wild-type U87-MG cells) and treated cells (U87-MG-shhsp90α and U87-MG-17AAG) (Table 1). The Akt/PKB kinase activity was significantly reduced upon inhibition of Hsp90 by 17AAG and shRNA oligonucleotide targeted against hsp90α. Statistical analysis using paired-sample t-test demonstrated **P < 0.001 for treated cells compared to untreated cells in U87-MG cell line showed a significant decrease in Akt kinase activity after hsp90α inhibition using 17AAG and shhsp90α. Note that shhsp90α was less effective compared to 17AAG.

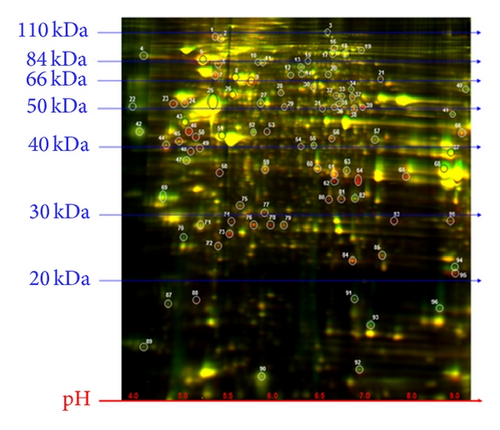

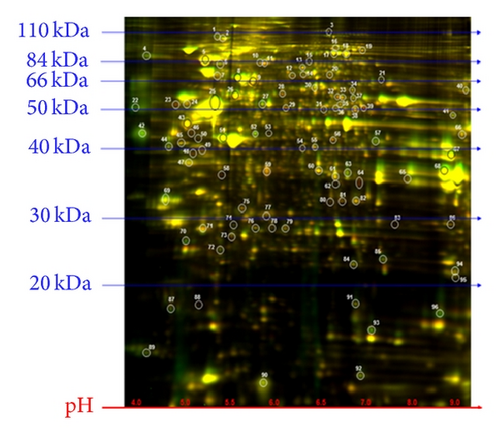

The U87-MG glioma cells were treated with 17AAG and transfected with shRNA targeting hsp90α to inhibit Hsp90 function. Proteins were isolated from the samples, and proteomic analysis was carried out. A comprehensive proteomic study was further performed on the control (wild-type U87-MG) and the treated (U87-MG-17AAG and U87-MG-shhsp90α) cell samples using 2D-DIGE and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Proteomic analysis revealed 96 spots to be differentially expressed by a volume ratio of 1.5-fold or greater after treatment across the three samples tested (Figure 2). The spots were selected upon DeCyder analysis, and some of the spots were differentially modified between the three treated groups to show a slight shift in molecular weights. Mass spectrophotometric analysis was carried out using MALDI-TOF and for protein identification, and 36 spots showing ≥2-fold change were selected (Table 2). The protein identification was carried out on the basis of peptide fingerprint mass mapping (MS data) and peptide fragmentation mapping (tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data). For the identification of proteins from their primary sequence databases, MASCOT search engine was used. From the 36 spots identified, 33 were identified as human proteins, while the other 3 were not elucidated (identified). More than one spot was identified as the same protein upon protein identification. This could have been attributed to the presence of different isoforms of the same protein following posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation or methylation which changes the proteins isoelectric point (pI) and/or molecular weight (MW) causing the spots to shift along with protein fragmentation.

| Protein | Accession number | Molecular function | Biological process | U87-MG-17AAG/U87-MG | U87-MG-shhsp90α/U87-MG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins upregulated by inhibition of Hsp90 by 17AAG and shRNA targeted towards hsp90α | |||||

| HSP70-1 (homosapiens) | gi|4529893 | Chaperone activity | Protein metabolism | 7.8 | 1.3 |

| Hexokinase 1, isoform CRA_d (homosapiens) | gi|119574708 | Catalytic activity | Metabolism, energy pathways | 4.5 | 1.9 |

| Tumor rejection antigen (gp96) 1 variant (homosapiens) | gi|62088648 | Heat shock protein activity | Protein metabolism | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| Vimentin variant 3 (homosapiens) | gi|167887751 | Structural constituent of cytoskeleton | Cell growth and/or maintenance | 2 | 1.2 |

| Pyruvate kinase, muscle (homosapiens) | gi|127795697 | Kinase activity | Metabolism, energy pathways | 6.6 | 2.9 |

| Vimentin variant 3 (homosapiens) | gi|167887751 | Structural constituent of cytoskeleton | Cell growth and/or maintenance | 3.9 | 1.4 |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 (homosapiens) | gi|24234686 | Heat shock protein activity | Protein metabolism | 4.2 | 1.2 |

| Chain A, Crystal Structure of Aldose Reductase complexed with Dichlorophenylacetic acid | gi|119390284 | Oxidoreductase activity | Metabolism, energy pathway | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| Annexin I (homosapiens) | gi|4502101 | Calcium ion binding | Cell communication, signal transduction | 16.8 | 1.7 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (homosapiens) | gi|31645 | Catalytic activity | Metabolism, energy pathway | 8 | 1.9 |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal Esterase L1 (ubiquitin thiolesterase), Isoform CRA_c (homosapiens) | gi|119613387 | Ubiquitin specific protease activity | Protein metabolism | 2.2 | 1 |

| Heat shock protein 27 (homosapiens) | gi|662841 | Chaperone activity | Protein metabolism | 2.7 | 1.1 |

| Heat shock protein 27 (homosapiens) | gi|662841 | Chaperone activity | Protein metabolism | 2.7 | 1.2 |

| Actin related protein 2/3 complex Subunit 2 (homosapiens) | gi|5031599 | Cytoskeletal protein binding | Cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 2.9 | 1 |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 variants (homosapiens) | gi|62896815 | Heat shock protein activity | Protein metabolism | 4.5 | 1.3 |

| Proteins downregulated by inhibition of Hsp90 by 17AAG and shRNA targeted towards hsp90α | |||||

| X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 6 (Ku autoantigen, 70 kDa) (homosapiens) | gi|169145198 | DNA binding | Regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolism, DNA repair. | −3.7 | −1.2 |

| Vimentin (homosapiens) | gi|62414289 | Structural constituent of cytoskeleton | Cell growth and/or maintenance | −2.3 | −3.4 |

| Vimentin (homosapiens) | gi|62414289 | Structural constituent of cytoskeleton | Cell growth and/or maintenance | −2.1 | −1.3 |

| SERPINE1 mRNA binding protein 1 isoform 1 | gi|66346679 | RNA binding | Regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolism. | −2.2 | −1.4 |

| Calumenin isoform a precursor (homosapiens) | gi|4502551 | Calcium ion binding | Cell communication, Signal transduction | −1.9 | −2.5 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (homosapiens) | gi|4505763 | Catalytic activity | Metabolism, Energy pathways | −1.2 | −2 |

| Aldolase A, fructose-bisphosphate, isoform CRA_b | gi|119600342 | Lyase activity | Metabolism, Energy pathways | −2 | −1.6 |

| Predicted Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase-like 6 (homosapiens) | gi|169208088 | Catalytic activity | Metabolism, Energy pathways | −2.5 | −1.8 |

| Tropomyosin 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion protein (homosapiens) | gi|13274400 | Structural constituent of cytoskeleton | Cell communication, Signal transduction | −2 | −1.4 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit 12 | gi|10801345 | Translation regulator activity | Protein metabolism | −2.7 | −1.6 |

| Transgelin 2 (homosapiens) | gi|4507357 | Unknown | Unknown | −3 | −1 |

| Chain A, Cyclophilin B complexed with (d-(Cholinylester)ser8)-Cyclosporin | gi|1310882 | Unknown | Unknown | −3.7 | −1.8 |

| Proteins differentially expressed by inhibition of Hsp90 by 17AAG and shRNA targeted towards hsp90α | |||||

| Collagen, type VI, alpha 1 precursor (homosapiens) | gi|87196339 | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | Cell growth and/or maintenance | 2.1 | −1.5 |

| Chain A, structure of human Annexin A2 in the presence Of calcium ions | gi|56967118 | Calcium ion binding | Signal transduction, Cell communication | 2.1 | −1.1 |

| Heat shock protein beta-1 (homosapiens) | gi|4504517 | Chaperone activity | Protein metabolism | 2.3 | −1.2 |

| Chain A, Human manganese superoxide dismutase mutant Q143n | gi|2780818 | Superoxide dismutase activity | Cell proliferation, Anti-apoptosis, Cell growth and/or maintenance | 2.7 | −1.2 |

| Chain A, crystal structure of Ca2+-bound form of Des3-23alg-2 | gi|211939086 | Unknown | Apoptosis | 2.3 | −1.1 |

| Transgelin 2 (homosapiens) | gi|4507357 | Unknown | Unknown | 2.4 | −1.1 |

- Note: The lists of identified peptides having ≥2-fold change were searched against MASCOT database for the corresponding proteins. Proteins were categorized according to their change in expression after treatment with 17AAG and shRNA targeting hsp90α in U87-MG glioma cell line. Protein name, accession number, protein molecular function, biological function, and fold change (volume ratio treated/control) as generated by MASCOT and human protein research database are summarized.

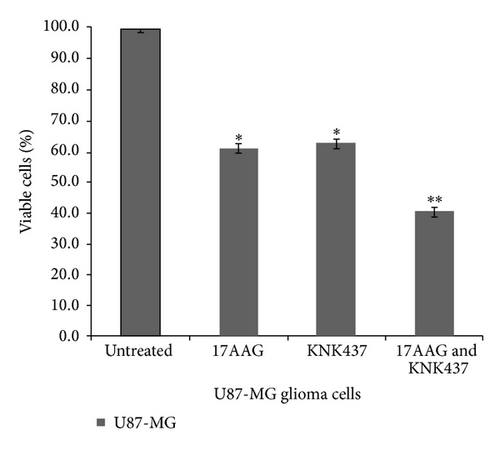

The U87-MG glioma cells were treated with IC50 values of 17AAG (0.25 μM) and KNK437 (55 nM) and then with a combination of IC50 values of 17AAG and KNK437 (Figure 3). CellTiter-Glo one solution assay (Promega, UK) was used (as described previously) to determine the number of viable cells present. The results show that combining 17AAG and KNK437 resulted in an increased cell death rate of U87-MG glioma cells (**P < 0.001).

4. Discussion

Hsp90 is upregulated in several human cancers, and targeting its function could be of therapeutic importance [2]. Previous studies have shown the presence of Hsp90 activity in glioma cell lines and tissues but not in normal brain cell lines or tissues [1, 19]. Hsp90 inhibitors exhibit antitumour activity by binding to Hsp90 and inducing proteosomal degradation of Hsp90 [20, 21]. As for 17AAG, a benzoquinone antibiotic derived from GA is a potent Hsp90 inhibitor, it dissociates the Hsp90 complex and leads to the inactivation of Hsp90 and eventually results in its degradation [22, 23]. Furthermore, it has been reported to inhibit tumour growth in cell lines and it is being examined in preclinical trials [22, 24, 25].

Cohorts of U87-MG cells were treated with 17AAG and shRNA to target hsp90α in this study. The Akt/PKB kinase activity was significantly reduced by 81 and 59.4%, (**P < 0.001), and the flow cytometric analysis showed a reduction in Hsp90α protein levels by approximately 44 and 16% after 17AAG and shhsp90α treatments, respectively (**P < 0.001). The reduction of Akt/PKB kinase protein was in agreement with previous studies which reported a dose dependent decrease in Hsp90 client proteins, namely, Akt after exposure, to 17AAG in murine neural stem cells and glioma stem cells [26]. Based on the previous literature reports and the laboratory findings, the inhibition of Hsp90 protein is a more effective therapeutic approach than silencing hsp90 gene since 17AAG showed a better silencing profile.

To understand the mechanisms involved or to characterize the changes caused at the cellular protein levels by inhibition of Hsp90, a differential proteomic analysis comparing control cells (wild-type U87-MG) and treated cells (U87-MG-shhsp90α and U87-MG-17AAG) was performed. The 2D-DIGE technique was carried out to separate the proteins, while MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was used for protein identification. Based on a 2-fold cut off, the analysis identified 36 proteins, while MALDI-TOF analysis identified 33 proteins with altered expressions showing > 99% confidence levels (3 protein being listed as unknown proteins).

On Hsp90 inhibition 15 proteins were found to be upregulated, of which 6 proteins are members of Hsp70 family together with Hsp27 and the gp96 which is a member of the Hsp90 family. These molecular chaperones serve as cochaperones to Hsp90 function [27, 28], thereby suggesting the role of Hsp90 cochaperones in compensating for Hsp90 function after Hsp90 inhibition. However, further research needs to be carried out to confirm these postulations. Members of the glycolysis pathways were also upregulated, demonstrating increased dependency on glycolysis for energy by the treated glioma cells. This phenomenon is described as the “Warburgs effect”, and it is an important phenomenon during malignant transformation [29]. The other proteins reported to be upregulated were vimentin, aldose reductase complexed with dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, annexin 1, ubiquitin thiolesterase isoform CRA_d, and actin related protein 2/3 complex subunit 2. Most of the proteins upregulated are involved in protein metabolism, energy pathways, cell growth and/or maintenance, metabolism, cell communication, signal transduction, and cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis. Their upregulation could be attributed to their functions which may assist U87-MG glioma cells to survive after Hsp90 inhibition. Thus, Hsp90 inhibition may be sublethal, and there is a need for a multitarget approach to glioma therapy.

As discussed earlier, it was observed that 17AAG inhibits Hsp90 greater than shRNA targeting hsp90α. A significant difference between the increase in some of the key proteins, namely, Hsp70-1, Hsc70, hexokinase 1, pyruvate kinase, GAPDH, and annexin 1 was observed between the two treatments, that is, 17AAG and shRNA targeting hsp90α.

Several proteins such as Ku autoantigen, vimentin, serpine1 mRNA binding protein 1, calumenin, phosphoglycerate kinase, aldolase A, tropomyosin 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion protein, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, transgelin 2, cyclophilin B complexed with (d-(cholinyester)ser8)-cyclosporin, and GAPDH (predicted) were downregulated. Some of the proteins downregulated after Hsp90 inhibition are involved in various cellular responses such as DNA repair, protein synthesis, and cell mobility. Most of the proteins downregulated such as Ku70, SERPINE1, PGK1, and transgelin after Hsp90 inhibition are normally upregulated in several tumours including gliomas [30–33]. Thus, their subsequent downregulation after Hsp90 inhibition could be of therapeutic importance. However, further work should be carried out to understand the interactions between the downregulated proteins and Hsp90 in the treatment of gliomas. Though certain proteins like vimentin and GAPDH are present in both upregulated and downregulated lists of proteins, it could be argued that they are different isoforms/variants of the protein (as seen in Table 2) which were possibly altered by negative and/or positive feedback mechanism and, hence, show presence in both upregulated and the downregulated lists. Further studies should be carried out to further understand the mechanism.

Proteomic analysis in this study showed induction of the Hsp70 family members after Hsp90 inhibition. Therefore, it can thereby be postulated that inhibition of Hsp70 together with Hsp90 could be of therapeutic importance in glioma therapy. Based on this hypothesis, U87-MG glioma cells were treated with both a Hsp90 inhibitor, that is, 17AAG and a Hsp70 inhibitor, that is, N-formyl-3,4-methylenedioxy-benzylidene-gamma-butyrolactam (KNK437). KNK437 is a benzylidene lactam compound which affects the induction of Hsp70 [34]. In addition to Hsp70, KNK437 has a considerable effect on the activation of the transcription factor, heat shock factor protein 1 (HSF1) and potentially inhibits the activity of Hsp40 and Hsp105, however, little is known about KNK437 and its mechanism [34]. This study in the light of previous finding examined the combined effect of inhibiting Hsp90 and Hsp70 with 17AAG and KNK437, respectively, in U87-MG glioma cell line.

Members of Hsp70 family act at multiple points in the apoptotic pathway and inhibit cell death [15–17]. Thus, even though Hsp90 was inhibited, the induction of Hsp70 after inhibition could have resulted in survival of the glioma cells (U87-MG). It can therefore be postulated that the inhibition of Hsp70 and Hsp90 would be of a therapeutic importance in glioma therapy. Based on this hypothesis, U87-MG glioma cells were treated with both the Hsp90 inhibitor, that is, 17AAG, and the Hsp70 inhibitor, that is, KNK437. The IC50 level of KNK437 was reported to be 55 nM, after 48 hours in the U87-MG cell line. Cell viability analysis demonstrated a higher percentage of U87-MG glioma cell death (~60%) (**P < 0.001) when treated with a combination of 17AAG and KNK437 compared to treatment with 17AAG alone which resulted in ~39% cell death. When U87-MG glioma cells were treated with only KNK437, there was ~37% cell death. However, the effects of 17AAG and KNK437 are not synergetic but rather additive in nature. Thus, it could be suggested that combination therapy involving inhibition of both Hsp90 and Hsp70 could be used for glioma therapy.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the pilot study showed that the treatment of U87-MG glioma cells with 17AAG and shRNA to target hsp90α, effectively reduced Hsp90α activity and subsequently reduced the Akt/PKB kinase activity in U87-MG cell line. These results suggest that inhibition of Hsp90 protein activity could be applied in the future glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) therapy.

The efficacy of Hsp90 inhibitors can be compromised by the induction of antiapoptotic Hsp70 isoforms as an off-target effect of Hsp90 inhibition. Subsequently, Hsp90 and Hsp70 were both inhibited by treating U87-MG cells with 17AAG and KNK437, respectively. An induced U87-MG cell death rate was observed when both Hsp90 and Hsp70 were simultaneously inhibited. These findings suggest the applying of a combination therapy in the management of GBM. We propose a further analysis of the effects of inhibiting Hsp90 and Hsp70 in combination for glioma studies. It is equally important to determine the cellular and subcellular mechanisms, wherebys KNK437 and 17AAG can induce cell death. Although proteomic screening identifies useful downstream effects of Hsp90 inhibition, the targets need further validation. The changes in protein expression and IPA analysis are indicative of alterations in multiple cell signalling pathways which need to be investigated.

Abbreviations

-

- 17AAG:

-

- 17-Allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin

-

- 2D-DIGE:

-

- Two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis

-

- FACS:

-

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

-

- Hsp:

-

- Heat shock protein

-

- IC50:

-

- Half-maximal inhibitory concentration

-

- KNK437:

-

- N-formyl-3,4-methylenedioxy-benzylidene-gamma-butyrolactam

-

- MALDI-TOF:

-

- Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight

-

- MS/MS:

-

- Tandem mass spectrometry

-

- shRNA:

-

- Short hairpin RNA

-

- SDS-PAGE:

-

- Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Conflict of Interests

The authors would like to indicate that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the Sydney Driscoll Neuroscience Foundation (SDNF).