Photocatalytic Decolourization of Direct Yellow 9 on Titanium and Zinc Oxides

Abstract

The photodecolourization of Direct Yellow 9, a member of the group of azo dyes which are commonly used in the various branches of the industry, was investigated. The photostability of this dye was not previously examined. Photocatalytic degradation method was evaluated. Solar simulated light (E = 500 W/m2), titanium dioxide, and zinc oxide were used as irradiation source and photocatalysts, respectively. Kinetic studies were performed on a basis of a spectrophotometric method. Degradation efficiency was assessed by applying high performance liquid chromatography. Disappearance of a dye from titanium dioxide and zinc oxide surfaces after degradation was confirmed by thermogravimetry and Raman microscopy. Direct Yellow 9 was found to undergo the photodegradation with approximately two times higher efficiency when zinc oxide was applied in comparison with titanium dioxide. A simple and promising way to apply the photocatalytic removal of Direct Yellow 9 in titanium dioxide and zinc oxide suspensions was presented.

1. Introduction

Wastewater from industry contains various organic compounds such as dyes, surfactants, excipients, and many others. Among all of them dyes are widely used in various branches of the textile industry, cosmetics, and paper production, in food technology, and so forth [1]. The amount of dyes produced in the world is estimated to be over 10,000 tons per year. Exact data on the quantity of dyes discharged in the environment are not available. However, it is assumed that a loss of 1-2% in production and 1–10% loss in use are a fair estimate [2].

Those substances enter the ecosystem modifying the environment and becoming a major threat for all forms of life [3]. Removing dyes is more important than colorless compounds, because even at a low concentration (below 1 ppm), they can change the color and the transparency of water [4]. Their presence in an aqueous environment decreases the sunlight penetration and consequently reduces an activity of a photosynthesis and a solubility of gases [5]. Furthermore, some dyes are toxic or potentially carcinogenic. In this connection, it is necessary to protect the environment against that pollution and decontaminate the sewage treatment plant effluents or industrial aquatic waste. Therefore, there is a necessity to apply efficient degradation techniques by factories and industrial plants where dyes are being created or applied during manufacturing process [6].

Traditional techniques such as biodegradation, adsorption, coagulation, reverse osmosis, and the others are ineffective for complete destruction of dyes [7]. Biodegradation, for instance, does not work efficiently because of a high resistance of dye molecules. Therefore, it can lead to the generation of hazardous aromatic amines [4]. Most of above-mentioned methods are nondestructive. They only transfer contaminations from solution to another phase, thus producing a large amount of sludge with a secondary pollution, which is difficult to remove [8]. Therefore, it is essential to consider other, more efficient and less invasive methods [9].

Recently, Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) seem to be an alternative to conventional treatment and can be successfully used to destruct dyes and other organic substances [10]. AOPs have employed photocatalysts, Fenton reagents, ozone, hydrogen peroxide, and ultraviolet or solar light, separately or combining some of them [11]. The mechanism is based on a generation of hydroxyl radicals which have one of the highest oxidative potential (E0 = +2.8 V) [12]. Hence, they are useful in a complete mineralization of organic water pollutants to carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic anions [13]. Among AOPs, heterogeneous photocatalysis with the usage of a semiconductor as a photocatalyst is a promising method for color removal from water [14].

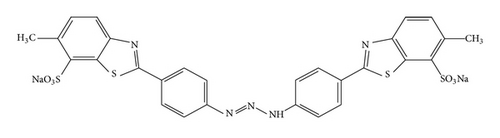

In performed studies two semiconductors, namely, TiO2 and ZnO, were used. Both of them are cheap, nontoxic, photochemically stable, environmentally friendly [13], and water insoluble [15], and they have similar energy of band gaps [16, 17]. Those catalysts were applied in a photodegradation of Direct Yellow 9 (DY9, Scheme 1), also known as Titan Yellow, Clayton Yellow, and Thiazole Yellow G, a dye which photostability was not previously examined.

DY9 is used as a stain and fluorescent indicator in microscopy. What is more, it was successfully applied in analytical methods of magnesium determination in serum [18], tissue [19], plant material [20] and rocks [21]. It was also used for estimation of beryllium in waste water [22], commercial aminoglycoside antibiotics in serum samples [23], and tetracycline antibiotics in chook serum and human urine samples [24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

TiO2 (anatase, Sigma-Aldrich) and ZnO (Sigma-Aldrich), Direct Yellow 9 (Riedel-de-Haën AG), and ammonium reineckate-NH4[Cr(SCN)4(NH3)2]·H2O (BDH Chemicals Ltd, England) were used. All above-mentioned chemicals were analytical grade reagents and used without further treatment. HPLC-grade acetonitrile was purchased from Merck. All solutions were prepared using deionized water, which was obtained by Polwater apparatus.

2.2. Apparatus

UV spectrophotometric analyses were performed with a HITACHI U-2800A UV-VIS spectrophotometer equipped with a double monochromator and double beam optical system (190–700 nm). UV studies were done using 1 cm quartz cell. Optical density was recorded in the range of 190–560 nm, and the maximum absorption wavelength experimentally registered at λ = 408 nm was used for the calibration curve and further DY9 concentration measurements.

Photolytic as well as photocatalytic degradation experiments were carried out in a solar simulator apparatus, namely SUNTEST CPS+ (ATLAS, USA). The photon flux of solar simulated radiation was measured by chemical method—Reinecke’s salt actinometer [25]. The photon flux of solar simulated light of 500 W/m2 was 2.32 × 10−6 Einstein/s.

A Renishaw Raman InVia Microscope equipped with a high sensitivity ultralow noise CCD detector was employed. The radiation from an argon ion laser (785 nm) at an incident power of 1.15 mW was used as the excitation source. Raman spectra were acquired with 3 accumulations of 10 s each, 2400 L/mm grating, and using 20x objective.

Differential scanning calorimetric (DSC) and thermogravimetric (TGA) analyses were performed by a Thermal Analyzer TGA/DSC 1 (METTLER TOLEDO) with a heating rate of 15°C/min under nitrogen environment with flow rate = 20 mL/min. All runs were carried out from 25°C to 1550°C. The measurements were made in alumina crucibles with lids.

The chromatographic experiments with HPLC-UV system were carried out on a Thermo Separation liquid chromatograph. The chromatographic column Waters Spherisorb ODS-2 150 mm × 4.6 mm packed with 5 μm particle size was used. Separation was achieved using an isocratic method. The mobile phase consisted of an acetonitrile : water (60 : 40 v/v). The flow rate of the mobile phase was 1 mL/min, and the injection volume was 100 μL. The column was maintained at a room temperature. The eluent was monitored at 322 nm.

2.3. Photocatalytic Degradation Experiment

2.3.1. Direct Photolysis

All experiments were done using 50 mL glass cell. 20 mL of the working solution of Direct Yellow 9 (DY9) at the concentration 80 μmol·L−1 was subjected to irradiation by Solar Light simulator SUNTEST CPS+, ATLAS USA emitting radiation in the range 300–800 nm with intensity 500 W m−2 for two hours. pH of aqueous solution was adjusted with 0.1 mol·L−1 H2SO4 or 0.1 mol·L−1 NaOH. pH was measured with an Elmetron CP-501 pH-meter (produced by ELMETRON, Poland) equipped with a pH-electrode EPS-1 (ELMETRON, Poland). The temperature of samples room was adjusted to 35°C. The spectra of irradiated solutions were recorded every 15 min.

All tested samples were prepared in triplicate.

The photocatalytic degradation experiments were performed in 50 mL glass cell. The reaction mixture consisted of 20 mL of Direct Yellow 9 (DY9) sample (80 μmol·L−1) and a photocatalyst (1.5 g·L−1). Prior the irradiation the dye-catalyst suspension was kept in the dark with stirring for 1 hour to ensure an adsorption-desorption equilibrium. To determine the DY9 degradation, the samples were collected at regular intervals (15 min) and centrifuged to remove the photocatalyst.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Primary Studies

As presented in Figure 1, the absorption spectra of DY9 differ when registered at different pH. DY9 spectrum in neutral environment is characterized by three bands, namely, at 202, 322, and 408 nm. The band at 408 nm was applied for monitoring changes in DY9 concentration. It was observed that the shape and intensity of absorption bands depend on pH of solution. The native pH of aqueous solution of Direct Yellow 9 is 5.8. The increase in pH causes the increase in intensity of the band at 408 nm and decrease of bands intensity at 202 and 322 nm. The lowering in pH causes reduction of intensity of all peaks and small bathochromic shift of the band at analytical wavelength. The stability of examined dye under simulated solar radiation was checked. For this purpose solutions of DY9 at pH 2, 7, and 10 were prepared and subjected to irradiation in solar simulator chamber for 2 hours. The first-rate model of kinetics was assumed. The acquired experimental data showed that studied dye is photochemically stable. The changes in its concentration at pH 7 and 10 were negligible. The observed rate of reactions was 4 × 104 min−1. Slight reduction of DY9 concentration was observed at acidic pH. The observed rate of this process was 3.2 × 10−3 min−1.

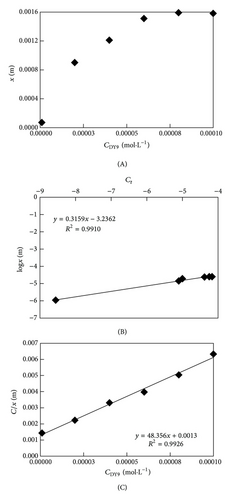

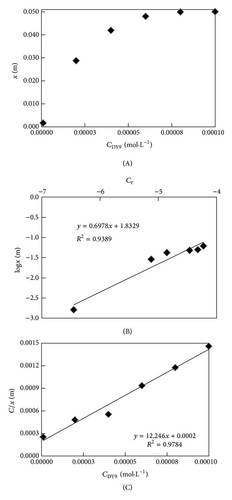

3.2. Adsorption Studies

3.3. Photodegradation Studies

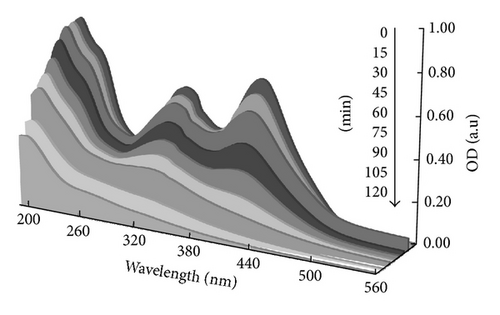

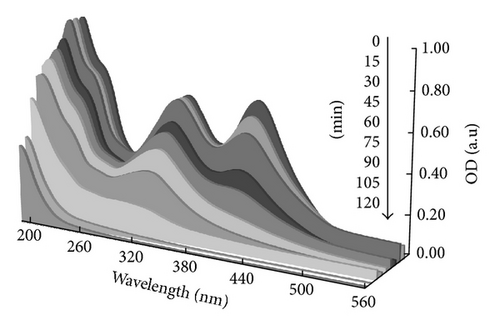

Photodegradation of DY9 was monitored spectrophotometrically. According to Figure 3, UV-Vis spectra taken during irradiation in the presence of both photocatalysts clearly depict the decreasing concentration of examined dye, which is due to its decomposition. On the basis of these studies the kinetics of the photocatalytic degradation was evaluated (described in Section 3.4).

Raman microscopy, thermogravimetry, and HPLC analyses were applied to reveal whether the photodegradation with the usage of TiO2 or ZnO is sufficiently destructive method to degrade DY9. Therefore, data before and after irradiation experiment (2 hours of irradiation) were presented.

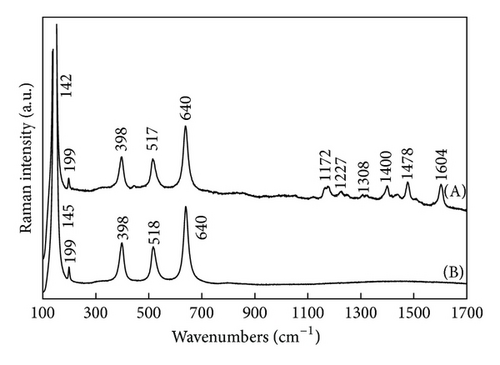

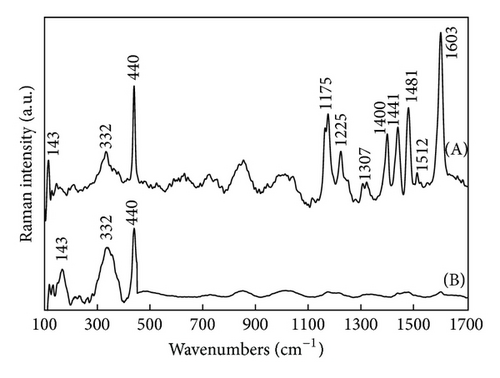

Raman spectra were registered to compare the adsorbed species present on the photocatalyst surface. Figure 4 shows the spectra of the examined samples taken by Raman microscope. In case of both semiconductors, after adsorption, without exposition to the solar light, in the region of 1100–1700 cm−1 certain bands appear. While after photodegradation almost no bands indicating DY9 presence on the surface can be seen. Moreover, on the images (taken by Raman microscope) of the semiconductors surface, yellowish spots present after adsorption were not found after irradiation treatment. Those results indicate that DY9 is adsorbed on the surface of both applied photocatalysts, and what is more, that the complete degradation of DY9 takes place.

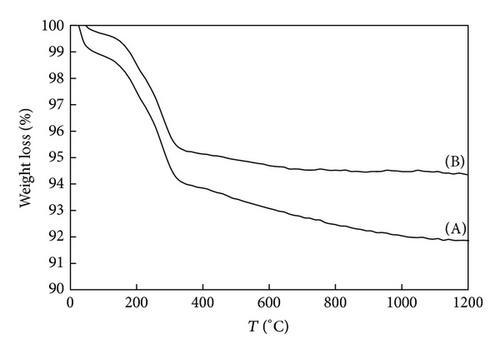

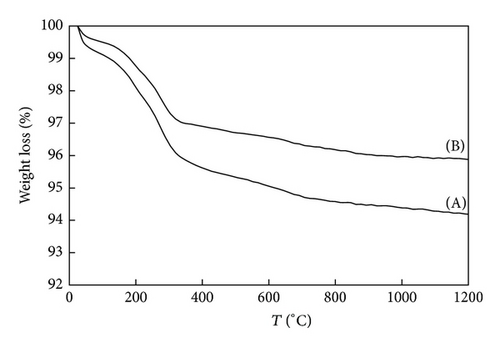

In order to confirm Raman spectroscopic results thermochemical characterization was performed. Thermogravimetric curves were presented in Figure 5. They indicate that after degradation a weight loss on the photocatalysts surface took place. This is due to the decomposition of a dye. This observation is true for both of used semiconductors. However, a slightly bigger weight loss was observed when TiO2 (2.2%) was applied in comparison with ZnO (1.9%). It could be influenced by the higher adsorption of DY9 on the TiO2 surface (8%) than on ZnO (5.8%).

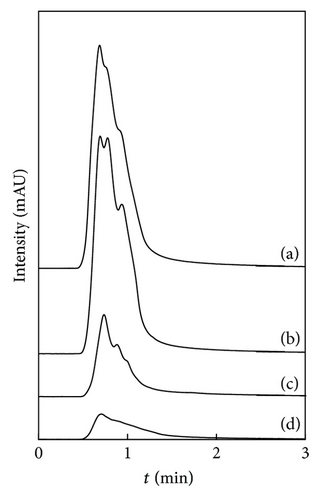

HPLC analyses (Figure 6) were performed in order to study whether any intermediate products after photocatalytic degradation of DY9 remained in the solution. It was found that even same photolysis of DY9 led to a slight decomposition of a dye since a tiny change in a peak shape was observed. However, only after addition of a photocatalyst a significant decrease in a peak height was noticed. HPLC analyses showed that photodegradation efficiency was more than two times bigger when ZnO was applied in comparison with the results obtained with TiO2.

HPLC analyses are in a good agreement with Raman microscopy as well as thermogravimetry results. They all indicate that ZnO leads to the higher photodegradation efficiency in comparison with TiO2.

3.4. Optimalisation of the Studied Process

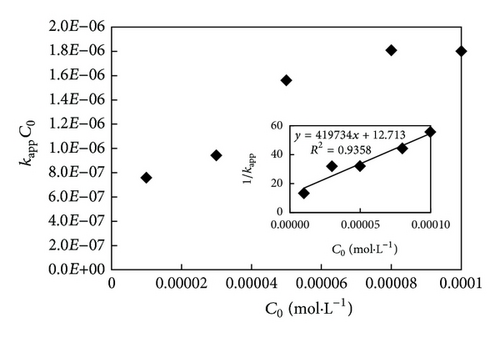

3.4.1. Effect of Dye Concentration

| DY9 concentration/μmol·L−1 | TiO2 (1.5 g·L−1) | ZnO (1.5 g·L−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | |

| 10 | 0.0758 | 9 | 0.0989 | 7 |

| 30 | 0.0314 | 22 | 0.0669 | 10 |

| 50 | 0.0312 | 22 | 0.0491 | 14 |

| 80 | 0.0226 | 31 | 0.0300 | 23 |

| 100 | 0.0180 | 39 | 0.0250 | 28 |

3.4.2. Effect of Catalyst Loading

The influence of the catalyst loading on the photodegradation process was studied. Kinetic values (kapp and t1/2 ) at varying catalysts loading were calculated and presented in Table 2. An increase of kapp with a decrease of t1/2 values was observed when the catalysts loading was increased. Following these observations, the amount of TiO2 and ZnO was kept constant at the optimal load of 1.5 g/L in all the subsequent photocatalytic degradation experiments.

| Catalyst loading/g·L−1 | TiO2 | ZnO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | |

| 0.1 | 0.0032 | 217 | 0.0049 | 141 |

| 0.5 | 0.0059 | 117 | 0.0124 | 56 |

| 1.0 | 0.0109 | 63 | 0.0138 | 50 |

| 1.5 | 0.0226 | 31 | 0.0300 | 23 |

3.4.3. Effect of pH

| pH | TiO2 | ZnO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | |

| 2 | 0.0282 | 25 | 0.0133 | 52 |

| 7 | 0.0226 | 31 | 0.0300 | 23 |

| 10 | 0.0183 | 38 | 0.0349 | 20 |

3.4.4. Effect of and Anions

| Addition of carbonate buffer | kapp/min−1 | t1/2/min | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | − | 0.0226 | 31 |

| + | 0.0147 | 47 | |

| ZnO | − | 0.0300 | 23 |

| + | 0.0172 | 40 |

4. Conclusions

DY9 was found to be resistant to the photolytic decomposition in aqueous environment, but it undergoes the photocatalytic degradation in suspension of both examined photocatalysts, namely TiO2, and ZnO. Two hours of irradiation upon solar simulated light led to the total decomposition of DY9 when ZnO was applied. In summary, we revealed the potential application of heterogeneous photocatalysis for DY9 removal from aquatic environment. Therefore, the current research can be considered as a step towards the commercialization of the photocatalytic removal of DY9 from the aqueous environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors kindly acknowledge the financial support from the National Science Centre, Poland (project 2012/05/N/ST5/01479). Thermogravimeter and Raman microscope were funded by EU, as part of the Operational Programme Development of Eastern Poland 2007–2013, Project no. POPW.01.03.00-20-034/09-00.