Some Properties of Motion Equations Describing the Nonlinear Dynamical Response of a Multibody System with Flexible Elements

Abstract

The industrial applications use instruments and machines operating at high speeds, developing high forces, low temperatures, corrosive environments, extreme pressures, and so forth. Under these conditions, the elasticity of elements such a machine is built of cannot be ignored anymore, and models are needed to more accurately “grasp” the mechanical phenomena accompanying the operation. The vibrations and the loss of stability are the main effects occurring under these conditions. For the study on this kind of systems with rigid motion and elastic elements, numerous models have been elaborated, the main idea being the discretization of the elements and the use of finite element method. Finally, second-order differential equations with variable coefficients are obtained; these equations are strong nonlinear ones due to the time-dependent values of angular speed and acceleration, and they can be linearized considering a very short period of time, in which the motion is considered to be “frozen.” The aim of this paper is to present some characteristic properties of these systems.

1. Introduction

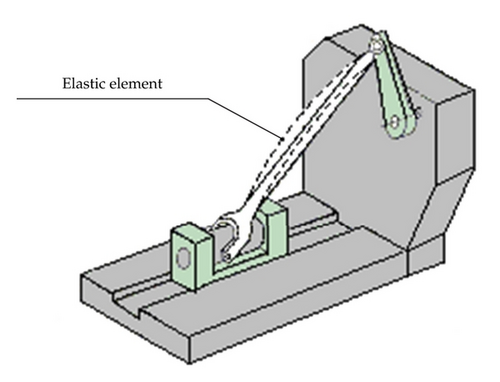

A mechanical system, a machine or instrument, is made up of elastic elements, the elasticity manifesting itself more or less. The rigid elements assumption generally made when studying such technical systems represents a first approximation leading to rapid results closer to reality. Depending on the given instrument operation conditions, this assumption may lead to correct results or to results considerably deviating from the real situation. If the instrument or the machine works with low operation speeds or if it is subjected to lower loads, then the model built based on the rigid elements assumption may lead to excellent results. The elasticity becomes a significant element if the loads occurred are high and/or the operation speeds are high (Figure 1). In this case, the deformations of the machine element will influence, usually in a negative way, the correct operation of the system. The resonance and the loss of stability represent the main forms of manifestation of elasticity. They will occur in the case of an inadequate design leading to a fast machine damage. The main method of approach of such a problem is the method of finite elements, a method used in a lot of works for elaborating models describing the behavior of machines containing elastic elements.

To summarize, matrices M, K, K(ω2) of the whole structure are symmetric and C, K(ε) are skew symmetric. New researches increase the complexity of the problem of the study of the multibody systems with flexible elements [13–17], but there are not many useful results concerning solving the equations. Some properties of such a system will be presented later.

2. Properties of Motion Equations of the Mechanical System

The motion equations of such system have properties allowing an easier solution of the equation system obtained but also a qualitative interpretation of the dynamic response of the system. We are presenting these properties as follows.

2.1. P1. In the Rayleigh Quotient, the Eigenvalues Do Not Depend Directly on the Damping Matrix

2.2. P2. Matrix A Defined by Relation (2.11) Has Two Null Eigenvalues

If n is the system dimension the dimension of matrix A will be 2n × 2n.

The equations allow the solutions qi = Ciexp (λi t).

If in the condition det (A − λE) = 0 we plug in λ = 0, we get the condition det A = 0.

It results in the possibility of avoiding the computation of the eigenvalues for matrix A with det A = 0, considering the fact that we know an eigenvalue λ1 = 0, and, by the transformation presented, we will compute the other eigenvalues as eigenvalues of B22.

To these two eigenvalues corresponds the nonharmonic solution q = C1t + C2 which will represent the rigid motion of the multibody system in a first approximation (C1 and C2 are integration constants). The other values are different from null for a multibody system with only one degree of mobility generally being different from each other.

3. Conclusions

The paper presents a few properties of motion equations in the case of mechanical systems having elastic elements. The properties are due to the existence of the skew-symmetric matrix C, by which the relative motion of nodal coordinates is manifested in case of applying the finite element method by the Coriolis effects. These properties allow a qualitative analysis of the obtained motion equations. Thus, the Coriolis effects due to the relative motions will determine a modification (generally small) of the systems eigenvalues. The Coriolis damping is not dissipative, meaning that the systems energy is not being influenced by the terms in which the skew-symmetric matrix C occurs. The last conclusion is that in case of modeling with the finite element method, the rigid motion, considered in a first approximation an a uniform motion of the system, can be eliminated from the motion equations written.

This fact also suggests the incremental solution of the problem on small periods of time in which the motion may be considered as “frozen” or uniform.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development (SOP HRD), financed from the European Social Fund, and by the Romanian Government under contract no. POSDRU/89/1.5/S/59323.