Development of Polymeric Cargo for Delivery of Photosensitizer in Photodynamic Therapy

Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), which employs photosensitizers (PSs), a light source with appropriate wavelength, and oxygen molecules, has potential for the treatment of various tumors and nononcological diseases due to its high efficiency in directly producing cellular death, vascular shutdown, and immune activation. After the clinical success of Photofrin (porphyrin derivative), many PSs were developed with improved optical and chemical properties. However, some weak points such as low solubility and nonspecific phototoxicity induced by hydrophobic PSs still remain. In order to overcome these problems, various polymeric carriers for PS delivery have been intensively developed. Here, we report recent approaches to the development of polymeric carriers for PS delivery and discuss the physiological advantages of using polymeric carriers in PDT. Therefore, this paper provides helpful information for the design of new PSs without the weaknesses of conventional ones.

1. Introduction

The therapeutic application of light began in 1900 when Raab reported that the combination of acridine orange and light could destroy living organisms (paramecium) [1].

Recently, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been intensively studied and employed as a modality for the treatment of various tumors and nononcological diseases due to its unique properties [2, 3]. This modality involves a noninvasive process that has minimal nonspecific effects on normal tissues, although some problems such as high cost and short-term period for retreatment still remain. PDT was first approved for skin cancer by the Canadian FDA in 1994. As illustrated in Figure 1 [4] PSs exposed to light of an appropriate wavelength are excited to singlet states (S1).PSs can relax back to ground state by emitting a fluorescent photon (S0) or be excited to triplet states via intersystem crossing (ISC; T1). From triplet excited states, PSs can relax back to ground state by emitting a phosphorescent photon or by transferring energy to another molecule via radiationless transition [5]. In addition, PSs can transfer energy to other molecules via type I and type II reaction processes. In the type I reaction, free radicals formed by hydrogen- or electron-transfer from PSs react with oxygen, thereby producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide () and peroxide anions (). In the type II reaction, PSs in the excited triplet state directly transfer energy to molecular oxygen in a triplet ground state (3O2), resulting in the formation of highly reactive singlet oxygen (1O2). In PDT, these ROS oxidize (photodamage) subcellular organelles and other biomolecules, leading to light-induced cell death. Indeed, PDT using PSs has been used to treat esophageal cancer in the United States and Canada, early- and late-stage lung cancer in The Netherlands, bladder cancer in Canada, and early-stage lung, oesophageal, gastric, and cervical cancers in Japan [6].

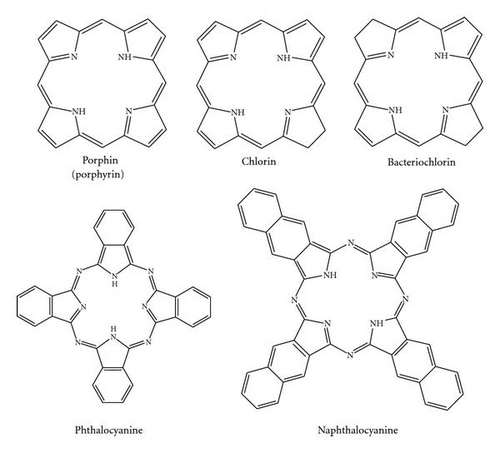

In this review, we focused on the key factors of PSs (PS type, light source, and oxygen molecules) in PDT, since the side effects and efficacy of PDT are determined by the properties of the PS. PSs were divided in three generations: 1st generation was based on porphyrin (first clinically used product) [5], 2nd generation was chlorin derivatives for improvement of solubility in water [7–10], and 3rd generation was polymeric PS with enhanced target specificity [11–17].

2. Photosensitizers (PSs)

The most commonly used and studied PSs to date are porphyrin derivatives such as Photofrin and Photogem. These materials are 1st generation PSs and are among the most useful PSs for clinical trials (Table 1) [2]. These PSs have absorption maxima in the red portion of the spectrum and are efficient singlet oxygen generators. Red absorption maxima allow activating light to penetrate deeper into tissue. However, these PSs readily accumulate and stay in normal skin for a longtime, leading to severe sunburning and photoreaction. Their side effects are inhibited by avoiding daylight and high-energy light, or by wearing protective clothing and sunglasses for approximately 6 weeks after treatment, all of which constitute a major limitation in clinical trials. To solve these problems, many researchers have synthesized 2nd generation PSs, which have improved physical properties such as high water solubility and photo-adsorption coefficient compared to 1st generation PSs (Figure 2). For this, second-generation PSs aim to have absorption maxima at wavelengths longer than 630 nm, since 1st generation PSs display relatively weak absorption at 630 nm that does not allow for optimal light penetration. Therefore, after a useful 2nd generation PS is identified, it is tested in vitro and in vivo for PDT activity [18].

| Sensitizer | Trade name | Potential indications | Activation wavelength |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPD (partially purified), porfimer sodium | Photofrin | Cervical endobronchial, oesophageal, bladder, gastric cancer, and brain tumors | 630 nm |

| BPD-MA | Verteporfin | Basal-cell carcinoma | 689 nm |

| m-THPC | Foscan | Head and neck tumors prostate and pancreatic tumors | 652 nm |

| 5- ALA | Levulan | Basal-cell carcinoma, head and neck, and gynaecological tumors | 635 nm |

| Diagnosis of brain, head and neck, and bladder tumors | 375~400 nm | ||

| 5-ALA-methylester | Metvix | Basal-cell carcinoma | 635 nm |

| 5-ALA-benzylester | Benzvix | Gastrointestinal cancer | 635 nm |

| 5-ALA-hexylester | Hexvix | Diagnosis of bladder tumors | 375~400 nm |

| SnETs | Purlytin | Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer, basal-cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and prostate cancer | 664 nm |

| Boronated protoporphyrin | BOPP | Brain tumors | 630 nm |

| HPPH | Photochlor | Basal-cell carcinoma | 665 nm |

| Lutetium texaphyrin | Lutex | Cervical, prostate, and brain tumors | 732 nm |

| Phthalocyanine-4 | Pc4 | Cutaneous/subcutaneous lesions from diverse solid tumor origins | 670 nm |

| Taporfin sodium | Talaporfin | Solid tumors from diverse origins | 664 nm |

- *5-ALA: 5-aminolevulinic acid; BPD-MA: benzoporphyrin derivative-monoacid ring A; HPD: hematoporphyrin derivative; HPPH: 2-(1-Hexyl-oxyethyl)-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-alpha; mTHPC: meta-tetrahydroxyphenylchlorin; SnET2: tin ethyl etiopurin.

Second-generation PSs based on chlorin show rapid clearance from the skin, and they were approved by the Japanese government and EU in 2003 [19–21]. Thus, PDT with 2nd generation PSs can reduce skin phototoxicity. However, the patient must stay in a darkened room for at least 2 weeks, and high target efficiency to the tumor site is required. To solve these problems, 3rd generation PSs were developed by chemical conjugation with biocompatible polymer and encapsulation in nanoparticles by physical interaction in order to reduce the toxicity to normal tissues and maximize tumor specificity. In particular, generation of PSs is often carried out by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), which can control the photoactivity of PSs by changing the environmental conditions. FRET is a distance-dependent interaction between the electronic excited states of two dye molecules in which excitation is transferred from a donor molecule to an acceptor molecule without emission of a photon [22].

3. Polymeric Carrier for Delivery of PSs

As mentioned above, PDT is often accompanied with long-lasting skin toxicity, which is a major limitation in its clinical application [2, 3, 5]. This effect is mainly due to the hydrophobic and nonspecific properties of PSs [23]. To improve the poor water solubility of PSs, a new concept was developed using polymeric carriers. In 1992, Kopecek’s group began a study using a polymer-PS conjugate [24].They reported N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer containing mesochlorin e6 monoethylene diamine disodium salt (Mce6). The Mce6 was bound via pendant enzymatically degradable oligopeptide side chains (G-F-L-G) in one copolymer and was attached through noncleavable side chains (G) in the other. Preliminary experiments were also undertaken to compare their localization/retention behavior and their tumoricidal activities in vivo (A/J mice; C1300 neuroblastoma). The results of localization/retention experiments found that Mce6 bound to the non-cleavable copolymer was retained in the tumor and other tissues for a prolonged time period compared to free Mce6 or Mce6 bound to cleavable copolymer. Light activation of Mce6 from the cleavable copolymer resulted in a substantially more potent biological response in vivo than did the permanently bound Mce6. It was thus hypothesized and indirectly supported by photophysical data that both of the polymer-photosensitizer complexes are aggregated (or conformationally altered) under physiological conditions due to their hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties. In buffer at pH 7.4, the quantum yield of singlet oxygen generation by free Mce6 was three-fold higher than that by Mce6 bound to non-cleavable copolymer; adding detergent increased the quantum yield of singlet oxygen generation to a value consistent with that of free Mce6. In vivo, if a sufficient time lag is allowed after drug administration for tumor cell lysosomal enzymes to cleave Mce6 from the polymer containing degradable side chains, then Mce6 is released in free form and behaves similar to the free drug. The other approach using a dendrimeric PS system was reported by Kataoka’s group [17, 25]. In that report, to enhance the efficacy of PDT, a new photosensitizer formulation, that is, dendrimer phthalocyanine- (DPc-) encapsulated polymeric micelle (DPc/m), was developed. DPc/m induced efficient and rapid cell death accompanied by characteristic morphological changes, such as blabbing of cell membranes, when the cells were photoirradiated using a low-power halogen lamp or high-power diode laser. Fluorescent microscopic observation using organelle-specific dyes demonstrated that DPc/m might accumulate in the endo-/lysosomes; however, upon photoirradiation, DPc/m might be promptly released into the cytoplasm and photodamage the mitochondria, which may account for the enhanced photocytotoxicity of DPc/m. This study also demonstrated that DPc/m displays significantly higher PDT efficacy in vivo than clinically used Photofrin (polyhematoporphyrin esters) in mice bearing human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Furthermore, DPc/m-treated mice did not show skin phototoxicity, which was also observed in the PHE-treated mice, under the tested conditions. These results strongly suggest the usefulness of DPc/m in clinical PDT. These systems are an attempt in PDT to enhance the tumor-specificity of PSs.

To date, a variety of polymeric carriers, including polymer-PS conjugates [26, 27], PS-loaded nanocarriers [15], long-circulating liposomes [28], and polymeric micelles [29–33], have been developed due to their passive targeting properties, which increase tumor-selective accumulation due to enhanced microvascular permeability via impaired lymphatic drainage in tumor tissue, a phenomenon which Maeda et al. termed the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [34–36].

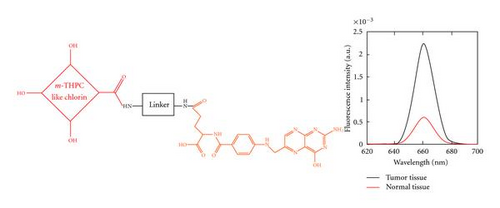

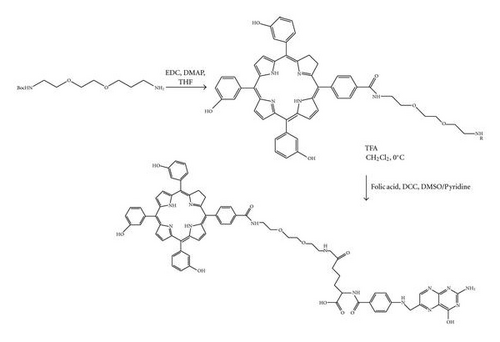

4. Polymeric Photosensitizer from Conjugation between Biocompatible Polymer and PSs

Conjugation technology was employed to improve the low tumor specificity of PSs. The method to conjugate a target specific ligand such as folate to PSs (Figure 3) operates by slightly increasing target specificity toward the tumor site [37]. However, different from expectations, the conjugates create new interactions between the molecules, due to high hydrophobicity or π-π stacking, which results in low stability. On the other hand, to improve the poor water solubility of PSs, simple substitutions with hydrophilic groups (carboxyl, sulfate groups) were studied. Unfortunately, this study led to quick clearance of PSs from the body, resulting in an increased injection dose. Indeed, Laserphyrin chlorin derivative substituted with carboxyl group requires a six-times higher dose than that of porphyrin [38]. Therefore, polymeric PSs composed of conjugate of biocompatible polymer and PS have been investigated to improve water solubility and tumor targeting via EPR. Polymeric PSs may also provide easy purification by using precipitation and dialysis methods.

PSs are characterized by high solubility in aqueous solution, slow clearance from the body, and great specificity for tumors via the EPR effect. In particular, carriers show a self-quenching effect for controlling PS phototoxicity in the circulation, suppressing it via fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) effect until they reach the target site, at which point the suppression can be rapidly reversed by the environmental conditions such as the enzyme [11–13, 39] and pH [16].

The enzymatically triggered photoactivity of polymeric PSs for tumor targeting was achieved by two methods based on the location of the enzyme, either extracellular or intracellular.

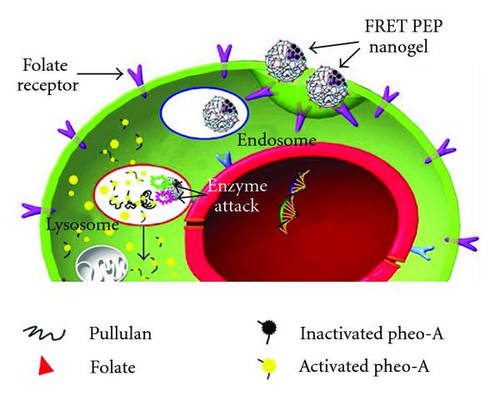

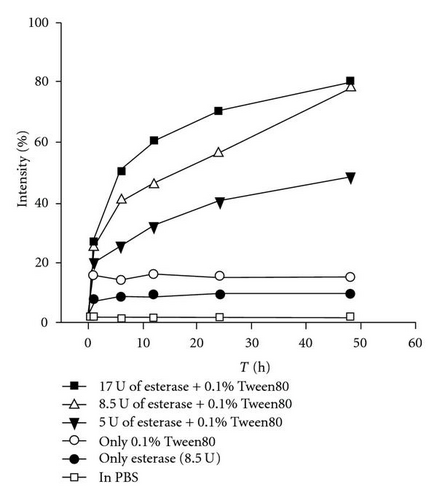

First, we reported the enzymatically triggered photoactivity of polymeric PSs by enzyme present in the cellular compartments. The concept of the system is shown in Figure 4(a). The system requires a ligand to uptake into the cell. Our group reported this system using pullulan/folate conjugate since folate receptor is overexpressed in tumor cells [40–43]. The conjugate did not show photoactivity during blood circulation due to self-quenching of PSs (FRET effect). However, when the conjugate was internalized in the cancer cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, photoactivity was restored due to loss of the FRET effect by enzymatic attack within cellular compartments such as lysosomes. As shown in Figure 4(b), when the esterase was treated with surfactant (0.1% Tween 80), polymeric PSs fluorescence dramatically increased to almost 80% of that of free PSs in organic solvent (DMSO or DMF). The intensity increased in proportion to the enzyme concentration, indicating that fluorescence was recovered by the enzymatic cleavage of the ester bond between pullulan and PSs. This suggests that as the polymeric PS is conjugated with the target ligand, it is easily internalized into the target cell. The property is very important to the accumulation of polymeric PSs at tumor site. Polymeric PSs entrapped at the tumor site via the EPR effect prevent the accumulation of other polymeric PSs at the site by blocking narrow blood vessels. Thus, entrapped polymeric PSs are rapidly internalized into the tumor cells to enhance their accumulation rate.

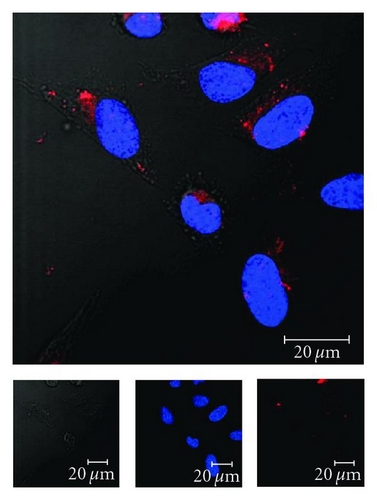

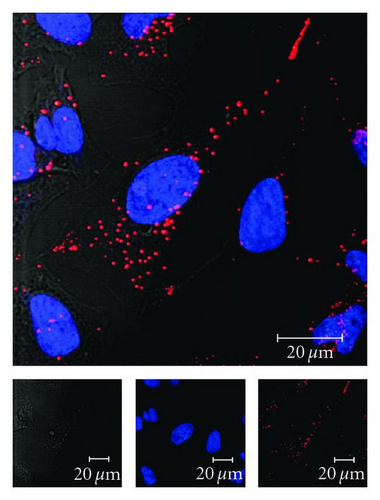

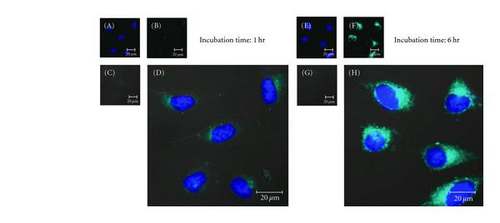

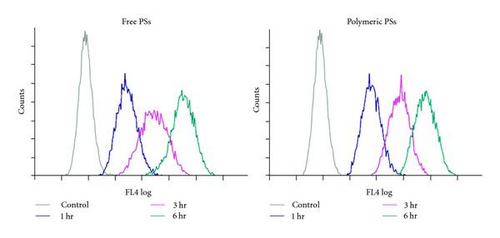

Our group reported polymeric PSs produced by conjugation of PSs with polymer possessing a target such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) [13, 39]. HA is a natural polymer common in the human body. It interacts with CD44 receptor, which is overexpressed in specific tumor cells [13, 44–46]. HA was acetylated prior to being dissolved in organic solvent and then conjugated with different amounts of PSs, resulting in the formulation of self-organizing polymeric PSs in aqueous solutions. The polymeric PS obtained was below 200 nm in size with a monodisperse size distribution. It was rapidly internalized into HeLa cells via an HA-induced endocytosis mechanism, a process that was blocked by the application of excess HA polymer (Figure 5). The results of the study indicate that HA-based polymeric PSs can potentially be applied in PDT. More recently, acetylated-chondroitin sulfate (CSA)/PS conjugates were synthesized via the formation of an ester linkage between CSA and PSs [39]. These conjugates in a HeLa cell culture system displayed rapid cellular uptake without any other ligands (Figure 6(a)) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis shows same result (Figure 6(b)). From these results, we suggest that this system may be instrumental in the design of new photodynamic therapies aiming to minimize phototoxicity.

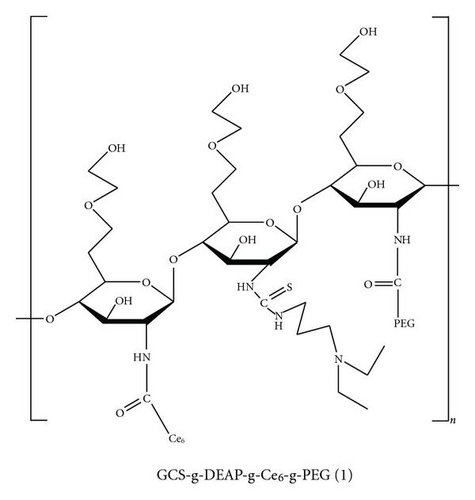

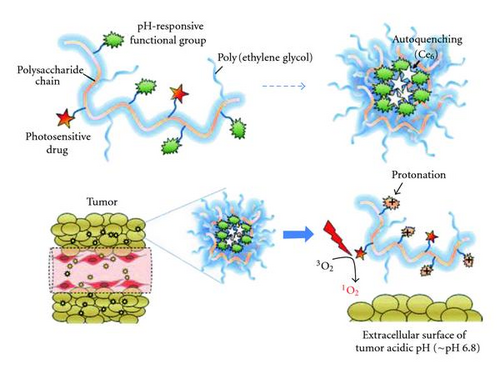

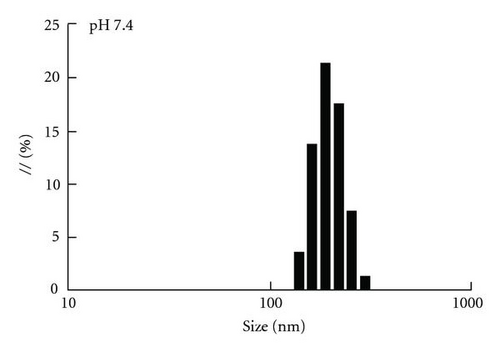

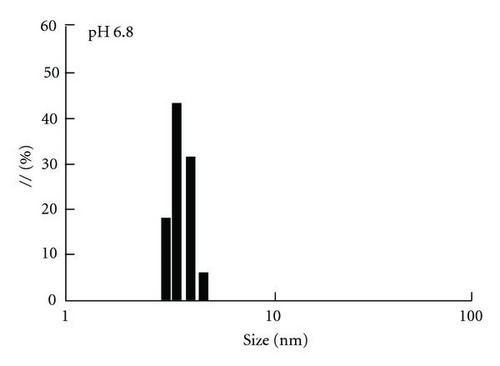

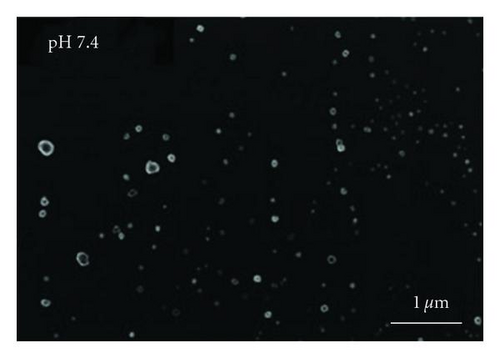

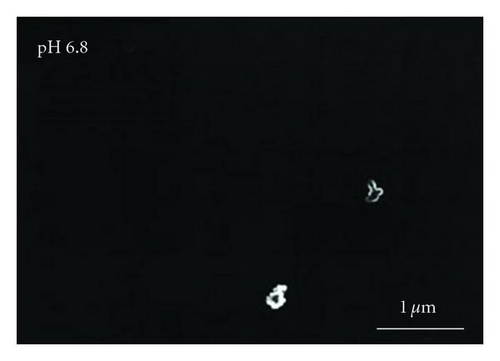

Recently, polymeric PS with pH-triggered photoactivity was reported [26]. The system exploited the difference in extracellular pH between tumor and normal tissues (Figure 7). The system is composed of glycol chitosan (GCS) and PEG blocks for the hydrophilic outer shell and 3-diethylaminopropyl isothiocyanate (DEAP, pH sensitive material) and PS blocks for the hydrophobic inner core. In particular, incorporation of a PEG block may improve the stability of the drug conjugate in serum as well as its penetration into tumor vasculature [27]. Upon encountering the tumor environment, the polymeric carrier-PS conjugate undergoes conformational changes into an uncoiled structure. This unique trait of polymeric PSs was confirmed experimentally (Figures 8(a)–8(d)). The magnitude of the particle-size changes for the polymeric PSs was large between pH 7.4 and 6.8; that is, the particle was 150 nm in diameter at pH 7.4 and 3.4 nm at pH 6.8. Figure 8(c) shows that polymeric PS was almost spherical in shape at pH 7.4. However, it became disentangled at pH 6.8, although very few aggregates were observed in this case (Figure 8(d)). Moreover, the zeta potential of polymeric PSs changed from −8.0 mV to +1.3 mV as the pH of the solution decreased from pH 7.4 to 6.8; the negative value originated from the PEG block at pH 7.4 and was offset by the protonation of the DEAP block at pH 6.8 (Figure 8(e)). It is known that the extracellular pH value in most clinical tumors is more acidic (pH, 6.5–7.0) than in normal tissues (ca. pH 7.4) [47, 48]. The different response of polymeric PSs at pH 7.4 (normal tissue pH) and at pH 6.8 (pH in tumors) presents a new route for the functionalization of photosensitizing drug conjugates.

5. Physical Loaded PSs in Nanocarriers

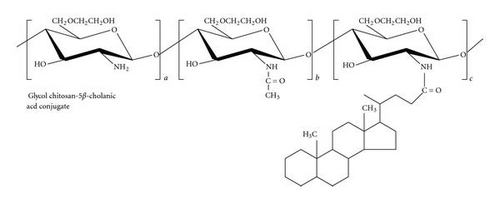

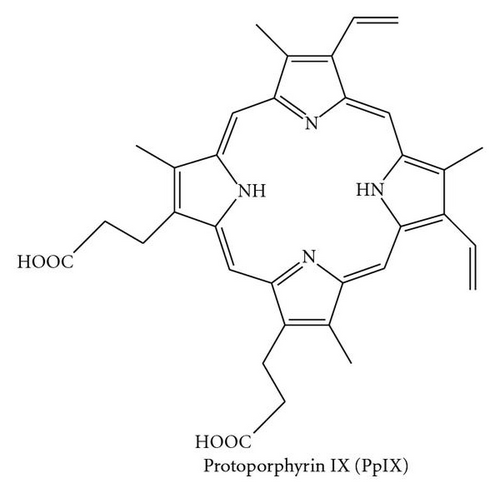

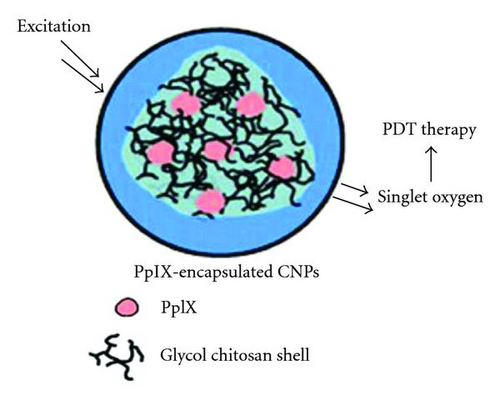

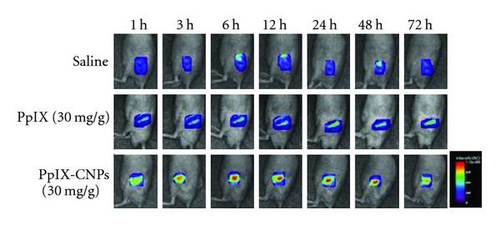

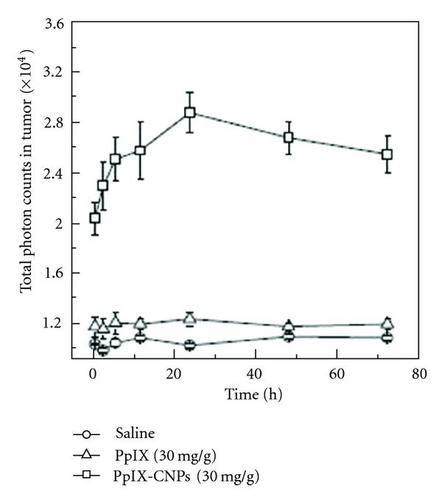

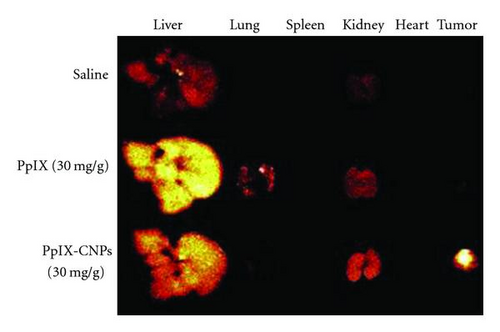

On the other hand, various nanocarriers with biodegradable and biocompatible polymers have been investigated for delivery of PSs. PSs are readily loaded in a nanocarrier by hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic moieties in the polymer and PSs. Hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan nanocarrier loaded with protoporphyrin IX (PpIX), which is a porphyrin-based PS (Figure 9) [15], has been reported. The nanocarrier range from 200~300 nm shows a much better accumulation rate at the tumor site than free PSs in vivo. In a previous study in SCC7 tumor-bearing mice, PpIX-glycol chitosan nanocarrier exhibited enhanced tumor specificity and increased therapeutic efficacy compared to free PpIX (Figure 10).Unfortunately, the system did not show controllable photoactivity via self-quenching, which can minimize damage against normal tissue and blood cells.

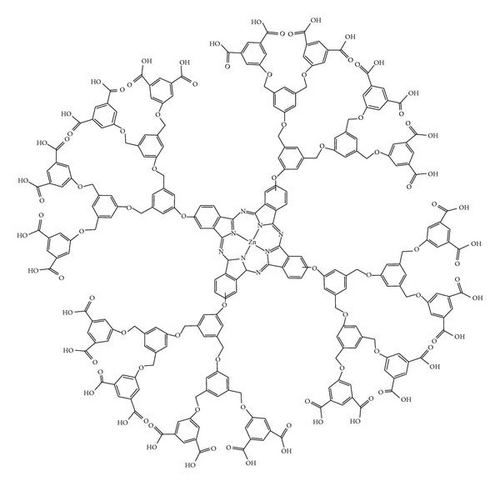

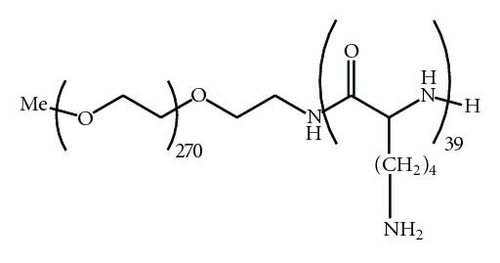

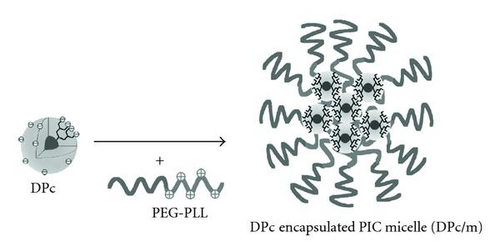

PSs were also loaded in nanocarriers via an ionic complex (Figure 11) [17]. In that study, the complex decreased the hydrophobicity of PSs, which produced a nanocarrier composed of a core with sufficient photoactivity and an outer shell with dendrimer form. The dendrimer form of PSs becomes available to ionic complex using PEG, which contains a cationic charge. PEG is well known for its strong hydrophilic groups, which increase the retention time in the blood circulation by exposure on the surface of the nanocarrier [49–52]. Further, this system increases the tumor target specificity by binding with antibody or a target moiety [34] and does not require control of drug release, which is always hurdle in drug delivery system. However, the system has side-effects associated with PDT such as skin toxicity.

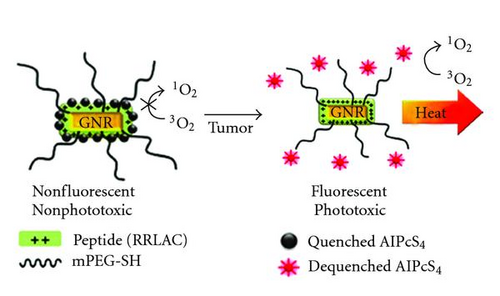

Recently, gold nanoparticles have been developed (Figure 12) [14], this gold nanorod-PS complex was developed for noninvasive near-infrared fluorescence imaging and cancer therapy. A previous study showed that fluorescence emission and singlet oxygen generation by AlPcS4 (photosensitizer, Al(III) phthalocyanine chloride tetrasulfonic acid) were quenched after complex formation with GNRs (gold nanorods); 4-fold greater intracellular uptake and better in vitro phototoxicity were observed in GNR-AlPcS4-treated cells than in free AlPcS4-treated cells, and after intravenous injection of the GNR-AlPcS4 complex, tumor sites were clearly identified in near-infrared fluorescence images as early as 1 h after injection. The tumor-to-background ratio increased over time and reached 3.7 at 24 h; tumor growth was reduced by 79% with photodynamic therapy (PDT) alone and by 95% with dual photothermal therapy (PTT) [53] and PDT. Based on these results, novel multifunctional nanomedicine may be useful for near-infrared fluorescence imaging and PTT/PDT in various cancers. Moreover, during circulation in the blood, these polymeric nanocarrier system can be completely suppressed until it reaches the target site, where the suppression can be rapidly reversed by decomplex. And, this system currently attempts the introduction of targeting ligands at the end of the PEG chain, which may further improve tumor targeting efficiency of GNR-PS complexes.

6. Conclusion

As suggested previously, many studies on PDT based on polymeric carriers such as polymeric PSs and nanocarrier loaded with PSs have been carried out in order to improve the poor water solubility and target specificity of PSs. For this purpose, polymeric carriers increase water solubility and targeting ratio. In particular, polymeric PSs composed of a conjugate of polymer and PS display controllable photoactivity between the target site and normal tissue via the FRET effect. And, this property provides the basis for various applications in the fields of diagnostics and biosensors. Although there are still tasks that must be solved, such as a more specific targeting rate, high photo-adsorption efficiency, and easy light source delivery to tumor sites, the development of polymeric carriers can dramatically increase the potential of PDT in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases.

Acknowledgments

This paper was financially supported by the Fundamental R&D Program for Core Technology of Materials, Republic of Korea, the Gyeonggi Regional Research Center (GRRC), the Korea Ministry of Education, Science and Technology through Strategic Research (2011-0028726), the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (PJ0071862011), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea, and Hi Seoul Science/Humanities Fellowship from Seoul Scholarship Foundation.