Instantons, Topological Strings, and Enumerative Geometry

Abstract

We review and elaborate on certain aspects of the connections between instanton counting in maximally supersymmetric gauge theories and the computation of enumerative invariants of smooth varieties. We study in detail three instances of gauge theories in six, four, and two dimensions which naturally arise in the context of topological string theory on certain noncompact threefolds. We describe how the instanton counting in these gauge theories is related to the computation of the entropy of supersymmetric black holes and how these results are related to wall-crossing properties of enumerative invariants such as Donaldson-Thomas and Gromov-Witten invariants. Some features of moduli spaces of torsion-free sheaves and the computation of their Euler characteristics are also elucidated.

1. Introduction

Topological theories in physics usually relate BPS quantities to geometrical invariants of the underlying manifolds on which the physical theory is defined. For the purposes of the present article, we will focus on two particular and well-known instances of this. The first is instanton counting in supersymmetric gauge theories in four dimensions, which gives the Seiberg-Witten and Donaldson-Witten invariants of four-manifolds. The second is topological string theory, which is related to the enumerative geometry of Calabi-Yau threefolds and computes, for example, Gromov-Witten invariants, Donaldson-Thomas invariants, Gopakumar-Vafa BPS invariants, and key aspects of Kontsevich′s homological mirror symmetry conjecture.

From a physical perspective, these topological models are not simply of academic interest, but they also serve as exactly solvable systems which capture the physical content of certain sectors of more elaborate systems with local propagating degrees of freedom. Such is the case for the models we will consider in this paper, which are obtained as topological twists of a given physical theory. The topologically twisted theories describe the BPS sectors of physical models, and compute nonperturbative effects therein. For example, for certain supersymmetric charged black holes, the microscopic Bekenstein-Hawking-Wald entropy is computed by the Witten index of the relevant supersymmetric gauge theory. This is equivalent to the counting of stable BPS bound states of D-branes in the pertinent geometry, and is related to invariants of threefolds via the OSV conjecture [1].

From a mathematical perspective, we are interested in counting invariants associated to moduli spaces of coherent sheaves on a smooth complex projective variety X. To define such invariants, we need moduli spaces that are varieties rather than algebraic stacks. The standard method is to choose a polarization on X and restrict attention to semistable sheaves. If X is a Kähler manifold, then a natural choice of polarization is provided by a fixed Kähler two-form on X. Geometric invariant theory then constructs a projective variety which is a coarse moduli space for semistable sheaves of fixed Chern character. In this paper we will be interested in the computation of suitably defined Euler characteristics of certain moduli spaces, which are the basic enumerative invariants. We will also compute more sophisticated holomorphic curve counting invariants of a Calabi-Yau threefold X, which can be defined using virtual cycles of the pertinent moduli spaces and are invariant under deformations of X. In some instances the two types of invariants coincide.

An alternative approach to constructing moduli varieties is through framed sheaves. Then there is a projective Quot scheme which is a fine moduli space for sheaves with a given framing. A framed sheaf can be regarded as a geometric realization of an instanton in a noncommutative gauge theory on X [2–4] which asymptotes to a fixed connection at infinity. The noncommutative gauge theory in question arises as the worldvolume field theory on a suitable arrangement of D-branes in the geometry. In Nekrasov′s approach [5], the set of observables that enter in the instanton counting are captured by the infrared dynamics of the topologically twisted gauge theory, and they compute the intersection theory of the (compactified) moduli spaces. The purpose of this paper is to overview the enumeration of such noncommutative instantons and its relation to the standard counting invariants of X.

-

(1) D6-D2-D0 bound states in D6-brane gauge theory—These compute Donaldson-Thomas invariants and describe atomic configurations in a melting crystal model [6]. This also provides a solid example of a (topological) gauge theory/string theory duality. The counting of noncommutative instantons in the pertinent topological gauge theory is described in detail in [7, 8].

-

(2) D4-D2-D0 bound states in D4-brane gauge theory—These count black hole microstates and allow us to probe the OSV conjecture. Their generating functions also appear to be intimately related to the two-dimensional rational conformal field theory.

-

(3) D2-D0 bound states in D2-brane gauge theory—These compute Gromov-Witten invariants of local curves. Instanton counting in the two-dimensional gauge theory on the base of the fibration is intimately related to instanton counting in the four-dimensional gauge theory obtained by wrapping supersymmetric D4-branes around certain noncompact four-cycles C, and also to the enumeration of flat connections in Chern-Simons theory on the boundary of C. These interrelationships are explored in detail in [9–13].

These counting problems provide a beautiful hierarchy of relationships between topological string theory/gauge theory in six dimensions, four-dimensional supersymmetric gauge theories, Chern-Simons theory in three dimensions, and a certain q-deformation of two-dimensional Yang-Mills theory. They are also intimately related to two-dimensional conformal field theory.

2. Topological String Theory

The basic setting in which to describe all gauge theories that we will analyse in this paper within a unified framework is through topological string theory, although many aspects of these models are independent of their connection to topological strings. In this section, we briefly discuss some physical and mathematical aspects of topological string theory, and how they naturally relate to the gauge theories that we are ultimately interested in. Further details about topological string theory can be found in, for example, [14, 15], or in [16] which includes a more general introduction. Introductory and advanced aspects of toric geometry are treated in the classic text [17] and in the reviews [18, 19]. The standard reference for the sheaf theory that we use is the book [20], while a more physicist-geared introduction with applications to string theory can be found in the review [21].

2.1. Topological Strings and Gromov-Witten Theory

The corresponding topological string amplitudes Fg have interpretations in compactifications of Type II string theory on the product of the target space X with four-dimensional Minkowski space ℝ3,1. For instance, at genus zero the amplitude F0 is the prepotential for vector multiplets of 𝒩 = 2 supergravity in four dimensions. The higher genus contributions Fg, g ≥ 1 correspond to higher derivative corrections of the schematic form R2T2g−2, where R is the curvature and T is the graviphoton field strength. We will now explain how to compute the amplitudes Fg. There are two types of topological string theories that we consider in turn.

2.1.1. A-Model

2.1.2. B-Model

There is a canonical stack line bundle 𝔏 → 𝔐g with fibre over the moduli point [Σg], the cotangent space of Σg at some fixed point. We define the tautological class ψ to be the first Chern class of 𝔏, ψ : = c1(𝔏) ∈ H2(𝔐g, ℚ). The Hodge bundle 𝔈 → 𝔐g is the complex vector bundle of rank g whose fibre over a point Σg is the space of holomorphic sections of the canonical line bundle . Let λj∶ = cj(𝔈) ∈ H2j(𝔐g, ℚ). A Hodge integral over 𝔐g is an integral of products of the classes ψ and λj.

2.2. Open Topological Strings

2.3. Black Hole Microstates and D-Brane Gauge Theory

When X is a Calabi-Yau threefold, certain BPS black holes on X × ℝ3,1 can be constructed by D-brane engineering. D-branes in X correspond to submanifolds of X equipped with vector bundles with connection, the Chan-Paton gauge bundles, and they carry charges associated with the Chern characters of these bundles. This data defines a class in the differential K-theory of X, which provides a topological classification of D-branes in X.

- (i)

D6-brane charge 𝒬6,

- (ii)

D4-branes wrapping an ample divisor

(2.20)with respect to a basis of four-cycles Ci, i = 1, …, b4(X) = b2(X), of X, - (iii)

D2-branes wrapping a two-cycle

(2.21) - (iv)

D0-brane charge 𝒬0.

3. D6-Brane Gauge Theory and Donaldson-Thomas Invariants

In this section we will look at a single D6-brane (𝒬6 = 1) and turn off all D4-brane charges (). We will discuss various physical theories which are modelled by the D6-brane gauge theory in this case, but otherwise have no a priori relation to string theory. These will include a tractable model for quantum gravity and the statistical mechanics of certain atomic crystal configurations. From the perspective of enumerative geometry, these partition functions will compute the Donaldson-Thomas theory of X.

3.1. Kähler Quantum Gravity

- (1)

we can make a singular gauge field A nonsingular on the blow-up

(3.7)of the target space, obtained by blowing up the singular points of A on X into copies of the complex projective plane ℙ2. This means that the quantum gravitational path integral induces a topology change of the target space X. This is referred to as “quantum foam” in [23, 24], or - (2)

we can relax the notion of line bundle to ideal sheaf. Ideal sheaves lift to line bundles on . However, there are “more” sheaves on X than blow-ups of X.

As we will discuss in detail in this section, this construction is realized explicitly by considering a noncommutative gauge theory on the target space X = ℂ3. We will see that the instanton solutions of gauge theory on a noncommutative deformation are described in terms of ideals ℐ in the polynomial ring ℂ[z1, z2, z3]. For generic X, the global object that corresponds locally to an ideal is an ideal sheaf, which in each coordinate patch Uα ⊂ X is described as an ideal in the ring of holomorphic functions on Uα. More abstractly, an ideal sheaf is a rank one torsion-free sheaf ℰ with c1(ℰ) = 0. This is a purely commutative description, since the holomorphic functions on ℂ3 form a commutative subalgebra of for the Moyal deformation that we will consider. Thus the desired singular gauge field configurations will be realized explicitly in terms of noncommutative instantons [23, 24].

3.2. Crystal Melting and Random Plane Partitions

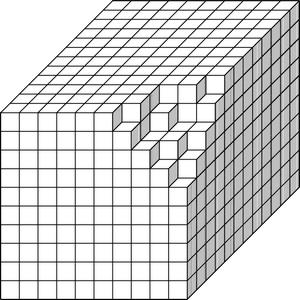

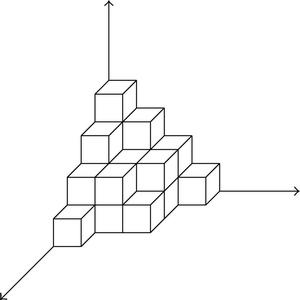

As we will see, the counting of ideal sheaves is in fact equivalent to a combinatorial problem, which provides an intriguing connection between the Kähler quantum gravity model of Section 3.1. and a particular statistical mechanics model [6]. Consider a cubic crystal

located on the lattice . Suppose that we start heating the crystal at its outermost right corner. As the crystal melts, we remove atoms, depicted symbolically here by boxes, and arrange them into stacks of boxes in the positive octant. Owing to the rules for arranging the boxes according to the order in which they melt, this configuration defines a plane partition or a three-dimensional Young diagram.

Removing each atom from the corner of the crystal contributes a factor q = e−μ/T to the Boltzmann weight, where μ is the chemical potential and T is the temperature.

3.3. Six-Dimensional Cohomological Gauge Theory

- (1)

a topological twist of maximally supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory in six dimensions,

- (2)

the dimensional reduction of supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory in ten dimensions on X,

- (3)

the low-energy effective field theory on a D6-brane wrapping X in Type IIA string theory, with D2 and D0 brane sources.

- (i)

the Donaldson-Uhlenbeck-Yau (DUY) equations expressing Mumford-Takemoto slope stability of holomorphic vector bundles over X with finite characteristic classes,

- (ii)

BPS solutions in the gauge theory which correspond to (generalized) instantons,

- (iii)

bound states of D0–D2 branes in a single D6-brane wrapping X.

Recall that (3.14) and (3.15) are a special instance of the Hermitean Yang-Mills equations in which a constant λ is added to the right-hand side of (3.15). These equations arise in compactifications of heterotic string theory. The condition that the compactification preserves at least one unbroken supersymmetry requires λ = 0. These are the natural BPS conditions on a Kähler manifold (X, ω0) which generalize the usual self-duality equations in four dimensions.

In order for the integral (3.17) to be well defined, we need to choose a compactification of 𝔐X. In light of our earlier discussion, we will take this to be the Gieseker compactification, that is, the moduli space of ideal sheaves on X. The corresponding variety 𝔐X stratifies into components Hilbn,β(X) given by the Hilbert scheme of points and curves in X, parameterizing isomorphism classes of ideal sheaves ℰ with ch1(ℰ) = c1(ℰ) = 0, ch2(ℰ) = −β, and ch3(ℰ) = −n. The partition function (3.17) is the generating function for the number of D0-D2 brane bound states in the D6-brane wrapping X. Mathematically, these are the Donaldson-Thomas invariants of X. We will define this moduli space integration, and hence these invariants, more precisely in Section 3.9.

3.4. Localization in Toric Geometry

Toric varieties provide a large class of algebraic varieties in which difficult problems in algebraic geometry can be reduced to combinatorics. Much of this paper will be concerned with these geometries as they possess symmetries which facilitate computations, particularly those involving moduli space integrations. Let us start by recalling some basic notions from toric geometry. Below we give the pertinent definitions specifically in the case of varieties of complex dimension three, the case of immediate interest to us, but they extend to arbitrary dimensions in the obvious ways.

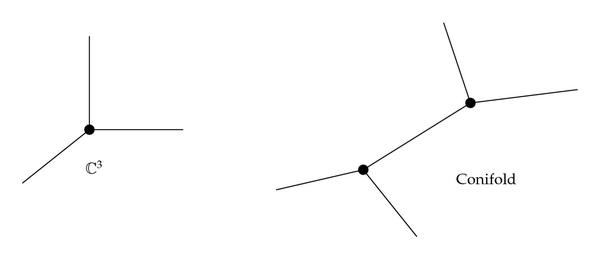

A smooth complex threefold X is called a toric manifold if it densely contains a (complex algebraic) torus T3 and the natural action of T3 on itself (by translations) extends to the whole of X. Basic examples are the torus T3 itself, the affine space ℂ3, and the complex projective space ℙ3. If in addition X is Calabi-Yau, then X is necessarily noncompact.

- (i)

a set of vertices f which are the fixed points of the T3-action on X, such that X can be covered by T3-invariant open charts homeomorphic to ℂ3,

- (ii)

a set of edges e which are T3-invariant projective lines ℙ1 ⊂ X joining particular pairs of fixed points f1, f2,

- (iii)

a set of “gluing rules” for assembling the ℂ3 patches together to reconstruct the variety X. In a neighbourhood of each edge e, X looks like the normal bundle over the corresponding ℙ1. Since this normal bundle is a holomorphic bundle of rank two and every bundle over ℙ1 is a sum of line bundles (by the Grothendieck-Birkhoff theorem), it is of the form

(3.20)for some integers m1, m2. The normal bundle in this way determines the local geometry of X near the edge e via the transition function(3.21)between the corresponding affine patches (going from the north pole to the south pole of the associated ℙ1). In the Calabi-Yau case, the Chern numbers c1(X) = 0 and c1(ℙ1) = 2 imply the condition m1 + m2 = 2.

3.5. Equivariant Integration over Moduli Spaces

Let Then is a universal principal -bundle, and there is a fibration with fibre 𝔐. Integration in equivariant cohomology is defined as the pushforward ∮𝔐 of the collapsing map 𝔐 → pt, which coincides with integration over the fibres 𝔐 of the bundle in ordinary cohomology. Let for i = 1, …, k and let ql : for l = 1, …, N be the canonical projections onto the ith and lth factors. Introduce equivariant parameters , with and , with .

The bundles , i = 1,2 for [ℰ] ∈ 𝔐X define a canonical Tk-equivariant perfect obstruction theory 𝔈• = (𝔈1 → 𝔈2) (see [22, Section 1]) on the instanton moduli space 𝔐 = 𝔐X. In this case, one may construct a virtual fundamental class [𝔐] vir and apply a virtual localization formula. The general theory is developed in [22] and requires a Tk-equivariant embedding of 𝔐 in a smooth variety 𝔜. The existence of such an embedding in the present case follows from the stratification of 𝔐X into Hilbert schemes of points and curves. Then one can deduce the localization formula over 𝔐 from the known ambient localization formula over the smooth variety 𝔜, as above. In this paper we will only need a special case of this general framework, the virtual Bott residue formula.

3.6. Noncommutative Gauge Theory

3.7. Instanton Moduli Space

3.8. Donaldson-Thomas Theory

This construction can be generalized to arbitrary toric Calabi-Yau threefolds X by using the gluing rules of toric geometry. The two simplest such varieties are described by the toric diagrams

- (1)

three-dimensional partitions πf at each vertex f of the toric diagram, corresponding to monomial ideals ℐf ⊂ ℂ[w1, w2, w3],

- (2)

two-dimensional partitions λe at each edge e of the toric diagram, representing the four-dimensional instanton asymptotics of πf.

This description requires generalizing the calculation on X = ℂ3 above to compute the perpendicular partition function Pλ,μ,ν(q) [6], which is defined to be the generating function for three-dimensional partitions with fixed asymptotics λ, μ, and ν in the three coordinate directions. Such partitions correspond to instantons on with nontrivial boundary conditions at infinity along each of the coordinate axes. It can be expressed in terms of skew Schur functions, with .

3.9. Wall-Crossing Formulas

The relationship (3.73) is in apparent contradiction with the OSV conjecture (2.25) if we wish to interpret the right-hand side as the generating function ZBH(1,0, ϕ2, ϕ0) of a suitable index for black hole microstates. However, the conjectural relations (2.25) and (3.73) hold in different regimes of validity. The number of BPS particles in four dimensions formed by wrapping supersymmetric bound states of D-branes around holomorphic cycles of X depends on the choice of a stability condition, and the BPS countings for different stability conditions are related by wall-crossing formulas. For example, stability of black holes requires that their chemical potentials μI lie in the ranges 𝒬0ϕ0 > 0 and .

From a mathematical perspective, we can study this phenomenon by looking at framed moduli spaces, which consist of instantons that are trivial “at infinity”. More precisely, we can consider a toric compactification of X obtained by adding a compactification divisor D∞, and consider sheaves ℱ with a fixed trivialization on D∞. The Kähler polarization defined by ω0 allows us to define the moduli space of stable sheaves. Then the symbolic definition of the gauge theory partition function (3.17) as a particular Euler characteristic can be made precise in the more local definition of Donaldson-Thomas invariants given by [40].

As a scheme with a perfect obstruction theory, the instanton moduli space 𝔐X can be viewed locally as the scheme theoretic critical locus of a holomorphic function, the superpotential W, on a compact manifold 𝒳 with the action of a gauge group 𝒢. 𝔐X has virtual dimension zero, and at nonsingular points, the obstruction sheaf 𝔑X on 𝔐X coincides with the cotangent bundle. Hence if 𝔐X were everywhere nonsingular, then the partition function (3.17) would just compute the signed Euler characteristic . At singular points, however, the invariants differ from these characteristics.

- (a)

surjections (framings)

(3.78)with ch(ℱ) = (1,0, β, n), - (b)

stable sheaves ℰ with ch(ℰ) = (1,0, −β, −n) and trivial determinant,

- (c)

subschemes S ⊂ X of dimension ≤1 with curve class [S] = β and holomorphic Euler characteristic χ(𝒪S) = n.

The equivalences between these three descriptions are described explicitly for X = ℂ3 in [7, 8].

As we vary the polarization ω0, the moduli spaces change and so do the associated counting invariants, leading to a wall-and-chamber structure. The wall-crossing behaviour of the enumerative invariants is studied in [41, 42]. The analog of varying ω0 for framed sheaves is to consider quotients of the structure sheaf 𝒪X in different abelian subcategories of the bounded derived category Db(coh(X)) of coherent sheaves on X. The analog of wall-crossing gives the Pandharipande-Thomas theory of stable pairs [43, 44] and the BPS invariants above. For this, the quotients of 𝒪X are the stable pairs (ℰ, α), where ℰ is a coherent 𝒪X-module of pure dimension one with ch2(ℰ) = −β and χ(ℰ) = −n, and α : 𝒪X → ℰ is a nonzero sheaf map such that coker(α) is of pure dimension zero, together with le Poitier′s δ-stability condition for coherent systems. In this case the change of Donaldson-Thomas invariants is described by the Kontsevich-Soibelman wall-crossing formula [42].

To cast these constructions into the language of noncommutative instantons, a proper definition of noncommutative toric manifolds is desired, beyond the heuristic approach presented above whereby only open ℂ3 patches are deformed. Isospectral type deformations of toric geometry, and instantons therein, are investigated in [45]. It may also aid in the classification of U(N) noncommutative instantons on ℂ3 for rank N > 1, along the lines of what was done in Section 3.7. (See [7, 8] for some explicit examples.) This appears to be related to the problem of defining a nonabelian version of Donaldson-Thomas theory which counts higher-rank torsion-free sheaves, for which no general, appropriate notion of stability is yet known.

4. D4-Brane Gauge Theory and Euler Characteristics

In this section we will take 𝒬6 = 0 (no D6-branes) and consider N D4-branes wrapping a four-cycle C ⊂ X. In this case the worldvolume gauge theory on the D4-branes is the 𝒩 = 4 Vafa-Witten topologically twisted U(N) Yang-Mills theory on C, where the topological twist is generically required in order to realize covariantly constant spinors on a curved geometry. When the gauge theory is formulated on an arbitrary toric singularity C in four dimensions, we may regard C as a four-cycle inside the Calabi-Yau threefold X = KC, and we will obtain an explicit description of the instanton moduli spaces and their Euler characteristics. The precise forms of the partition functions will be amenable to checks of the OSV conjecture (2.25), and hence a description of wall-crossing phenomena.

4.1. 𝒩 = 4 Supersymmetric Yang-Mills Theory on Kähler Surfaces

Vafa and Witten [46] introduced a topologically twisted version of 𝒩 = 4 supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory in four dimensions. The twisting procedure modifies the quantum numbers of the fields in the physical theory in such a way that a particular linear combination of the supercharges becomes a scalar. This scalar supercharge is used to define the cohomological field theory and its observables on an arbitrary four-manifold C. In the following we will only consider the case where C is a connected smooth Kähler manifold with Kähler two-form k0. When certain conditions are met, the partition function of the twisted gauge theory computes the Euler characteristic of the instanton moduli space.

4.2. Toric Localization and the Instanton Moduli Space

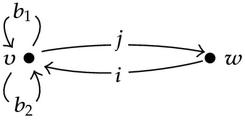

Instantons on C = ℂ2 can be described as follows. Consider the quiver

The classification of toric fixed points is given in [49], by identifying the instanton moduli space 𝔐1,k(ℂ2) with the Hilbert scheme of points (ℂ2) [k]. The fixed points are point-like instantons which are in one-to-one correspondence with Young tableaux λ having |λ | = k boxes. In the more general case of a U(N) gauge theory in the Coulomb branch, one takes N copies of the U(1) theory and the fixed points are classified in terms of N-tuples of Young diagrams , called N-coloured Young diagrams. One can show that the fixed points are isolated.

4.3. Hirzebruch-Jung Spaces

4.3.1. Local ℙ1

Setting n = 1, the space C(p, 1) can be identified with the total space of the holomorphic line bundle over ℙ1 of degree −p, with ℓ = 1 and e1 = p. In this case, S = ℙ1 is the zero section divisor. In the context of topological string theory, such four cycles appear in the “local” Calabi-Yau threefolds X which are regarded as neighbourhoods of a holomorphically embedded rational curve in a compact Calabi-Yau threefold, that is, as the normal bundle 𝒩 → ℙ1. Since 𝒩 is a holomorphic vector bundle of rank two over ℙ1 and the Calabi-Yau condition implies c1(𝒩) = −χ(ℙ1) = −2, it follows that X is the total space of a bundle of the form .

4.3.2. Ap−1 ALE Space

The complex surface C = C(p, p − 1) is an example of an asymptotically locally Euclidean (ALE) space. This means that C carries a scalar flat Kähler metric g such that (C, g) is complete, and there exists a compact set K such that . Here ℤp ⊂ O(4) acts freely on and the metric g approximates the flat Euclidean metric on ℝ4. Such a coordinate system is called a coordinate system at infinity. We regard ℤp ⊂ U(2) acting on (z, w) ∈ ℂ2≅ℝ4 as described above (with n = p − 1), and the complex structure I on C approximates that on ℂ2 = ℝ4. As the resolution of the Klein singularity ℂ2/ℤp, C(p, p − 1) contains a chain of ℓ = p − 1 projective lines ℙ1, each with self-intersection number ei = 2. In this case, the intersection matrix C coincides with the Cartan matrix of the Ap−1 Dynkin diagram.

4.4. Instantons on ALE Spaces

We begin by describing in some detail the instanton moduli space in the case of the Ap−1 ALE spaces, for which a rigorous construction is known. U(N) instantons on ALE spaces are given by the ADHM construction. Since the topological gauge theory is invariant under blow-ups of the surface (using blow-up formulas), one can do the instanton computation on the orbifold ℂ2/Γ where Γ = Γ(p,p−1)≅ℤp. This result is at the heart of the McKay correspondence which provides a one-to-one correspondence between irreducible representations of the orbifold group Γ and tautological bundles over the exceptional divisors of the minimal resolution C = C(p, p − 1).

(4.32)

(4.32)4.4.1. Regular Instantons

4.4.2. Fractional Instantons

4.5. Instantons on Local ℙ1

Let us now discuss what is known beyond the ALE case, in the instance that C is the total space of the holomorphic line bundle [55]. In this case an ADHM construction is not available. Nevertheless, much of the construction in the ALE case carries through, and by introducing weighted Sobolev norms, one shows that 𝔐C is a smooth Kähler manifold with torsion-free homology groups which vanish in odd degrees. Let us consider some explicit examples.

The zero section of , considered as a divisor S = ℙ1 of C, produces a line bundle ℒ → C such that c1(ℒ) is the generator of H2(C, ℤ) = ℤ. It has a unique self-dual connection asymptotic to the trivial connection. Let be the trivial line bundle over C. Set , and let 𝔐(ℰ) be the moduli space of self-dual connections on ℰ which are asymptotic to the trivial connection at infinity. Then dim ℝ(𝔐(ℰ)) = 2p. Since H1(C, ℝ) = 0, using Morse theory one can show that the only nonvanishing homology groups of the instanton moduli space are H0(𝔐(ℰ), ℝ) = H2(𝔐(ℰ), ℝ) = ℝ.

Alternatively, set ℰ = ℒ ⊕ ℒ∨, and let 𝔐(k)(ℰ), k = 0,1, …, p − 1, be the moduli space of self-dual connections asymptotic to . Then for any p > 2, dim ℝ(𝔐(k)(ℰ)) = 2, while for p = 2 (whereby coincides with the A1 ALE space), one has dim ℝ(𝔐(k)(ℰ)) = 4. In particular, for p = 2 there is a diffeomorphism 𝔐(k)(ℰ)≅T*ℙ1 with H0(𝔐(k)(ℰ), ℝ) = H2(𝔐(k)(ℰ), ℝ) = ℝ, while for p = 4 one has 𝔐(k)(ℰ)≅B2. Instantons on local ℙ1 will be studied in more generality later on in terms of moduli spaces of framed torsion-free sheaves.

4.6. Wall-Crossing Formulas

- (a)

surjections (framings) 𝒪C → ℱ → 0 of torsion-free sheaves with ch(ℱ) = (N, d, −k),

- (b)

stable torsion-free sheaves ℰ on C with ch(ℰ) = (N, d, k),

- (c)

closed subschemes S ⊂ C of dimension ≤1 with dual curve class [S] ∨ = d and holomorphic Euler characteristic χ(𝒪S) = k.

In contrast to the six-dimensional situation, in four dimensions the connections between these three classes of objects are somewhat more subtle. We will examine each of them in turn and how they compare with the gauge theory results we have thus far obtained.

4.7. Moduli Spaces of Framed Instantons

We begin with Point (a) at the end of Section 4.6. Let C be a smooth, quasiprojective, open, toric surface. We will assume that C admits a projective compactification , that is, is a smooth, compact, projective, toric surface with a smooth divisor (called the “line at infinity”) which is a T2-invariant ℙ1 in , and such that . We will also require that ℓ∞ · ℓ∞ > 0, in addition to ℓ∞≅ℙ1. The difference between the counting of framed instantons on the compact toric surface (with boundary condition at “infinity”) and of unframed instantons on the open toric surface C is a universal perturbative contribution, which will be dropped here. Since is compact, these calculations will only capture the contributions from instantons with integer charges on C. We will mention later on how to incorporate the contributions from fractional instantons on C.

- (1)

ℰ has the following topological Chern invariants:

(4.51) - (2)

ℰ is locally-free in a neighbourhood of ℓ∞, and there is an isomorphism called the “framing at infinity”.

We will now describe a natural torus invariant subspace of the instanton moduli space. The T2-invariance of ℓ∞ implies that the pullback of the T2-action on defines an action on 𝔐N,d,k(C). There is also an action of the diagonal maximal torus TN of GL(N, ℂ) on the framing. Altogether we get an action of the complex algebraic torus on 𝔐N,d,k(C) [69]. We are interested in the fixed point set of this torus action.

Since the zero-cycles Zl are not supported on ℓ∞, they must be contained in the fixed point set V(C) in C. Thus each Zl is a union of subschemes f ∈ V(C) supported at the T2-fixed points pf ∈ C. If we choose a local coordinate system (x, y) ∈ ℂ2 in a patch Uf around pf, then the T2-invariant ideal of in the coordinate ring ℂ[x, y] of Uf≅ℂ2 is generated by the T2-eigenfunctions with nontrivial characters, which are monomials xiyj, and hence corresponds to a Young diagram with boxes (with monomial xiyj placed at (i + 1, j + 1)). The ideal is spanned by monomials outside the Young diagram. Likewise, since the T2-invariant two-cycles Dl are disjoint from the line at infinity, they are supported along the edges ℓe≅ℙ1, e ∈ E(C).

This formula differs from (4.43) in that only integral values of the first Chern class are permitted in (4.70). In the case of an Ap−1 singularity, fractional first Chern classes can be incorporated by constructing instead the moduli space of torsion-free sheaves on the orbifold compactification of the hyper-Kähler ALE space C, where [52, 55, 70, 71]. In a neighbourhood of infinity, we can approximate by ℙ2/Γ with the singularity at the origin resolved. More precisely, we obtain the divisor by gluing together the trivial bundle 𝒪C on C with the line bundle on ℙ2/Γ. The latter bundle has a Γ-equivariant structure such that the map is Γ-equivariant. Let us examine some examples which are covered by the analysis above.

4.7.1. Affine Plane

4.7.2. Local ℙ1

On these spaces, one also has a version of the Hitchin-Kobayashi correspondence which makes contact with the realization of instantons as self-dual connections. Namely, SU(N)-instantons on Cp are in one-to-one correspondence with holomorphic bundles ℰ of rank N on Cp with c1(ℰ) = 0 together with a framing at infinity [73]. When p = 2, these spaces coincide with the A1 ALE space.

4.7.3. Compact Surfaces

We will now examine situations under which the formula (4.70) holds in the case of compact surfaces, providing rigorous justification for some of the conjectural formulas of [56]. Let C be a compact, smooth, projective toric surface. Let c∞ be a generic point in C which is disjoint from the torus invariant lines ℓe, e ∈ E(C) of C. Let 𝔐N,d,k(C, c∞) be the moduli space of isomorphism classes [ℰ] of torsion-free coherent sheaves ℰ on C with topological Chern invariants as in (4.51), together with a “framing” at the point c∞. When ℰ is locally free, this framing means a choice of basis for the fibre space . When ℰ is not locally free, the framing is defined with respect to a locally free resolution ℰ• → ℰ → 0.

4.8. Stability

The following result computes the expected dimension of the instanton moduli space in this case.

Lemma 4.1. The virtual dimension of 𝔐N,d,k(C) equals 2N k + d2 − (N2 − 1) χ(𝒪C), where d2 : = ∫Cd∧d and χ(𝒪C) is the holomorphic Euler characteristic of C.

Proof. As discussed in Section 3.5., the dimension of the virtual tangent space to the instanton moduli space at a point [ℰ] ∈ 𝔐N,d,k(C) in obstruction theory is the difference of Euler characteristics . The latter quantity may be computed for ℰ locally free by using the Hirzebruch-Riemann-Roch theorem to write

The situation for higher rank N > 1 is much more complicated. In this case, slope-stability does not seem to properly account for walls of marginal stability extending to infinity which describe wall-crossing behaviour of the partition functions counting D4-D2-D0 brane bound states on Calabi-Yau manifolds X with h1,1(X) > 1 [64]. As discussed in Section 3.9., the physical theory is described by moduli spaces of stable objects in the derived category Db(coh(X)), as the observed D-brane decays are impossible in the abelian category coh(X) of coherent sheaves on X.

4.9. Perpendicular Partition Functions and Universal Sheaves

Finally, we come to the last Point (c) at the end of Section 4.6. For U(1) gauge theory, this relationship is analysed in detail in [54]. In this case a four-dimensional analog of the topological vertex formalism can be developed. On the gauge theory side, the vertex contributions should be computed by a version of the perpendicular partition function of Section 3.8., that is, the generating function for instantons on C = ℂ2 with fixed asymptotics such that , while the edge contributions should be read off from the character of the corresponding universal sheaf. In the remainder of this section, we will describe in detail the instanton moduli space with boundary conditions specified by integers m1, and m2, and show that the fixed point loci of the induced -action are enumerated by two-dimensional Young diagrams with asymptotics m1, and m2. This gives the four-dimensional version of the gauge theory gluing rules of Section 3.8. and also a first principle derivation of the empirical vertex rules of [54, Section 4.3].

4.9.1. Instanton Moduli Spaces on 𝔽0

Let be the moduli space of isomorphism classes [ℰ] of torsion-free sheaves ℰ on 𝔽0 with topological Chern invariants as in (4.51), where d = mzξz + mwξw, and nontrivial framings along the two independent “directions at infinity” are prescribed by two fixed isomorphisms and , where W is a fixed N-dimensional complex vector space. We will say that such a sheaf is “trivialized at infinity” if it is equipped with two isomorphisms and . The moduli space of trivialized sheaves is denoted 𝔐N,k(𝔽0): = 𝔐N;(0,0);k(𝔽0). These moduli spaces carry an obvious induced action of the torus , and the following formal arguments show that the instanton counting in these moduli spaces is the same as before.

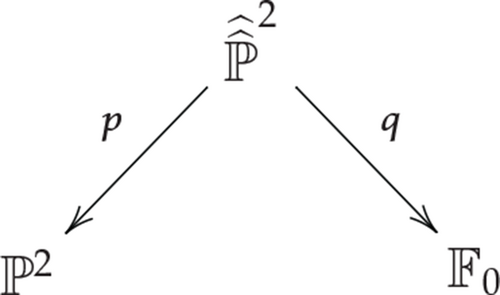

Proposition 4.2. There is a natural -equivariant birational equivalence between the moduli spaces

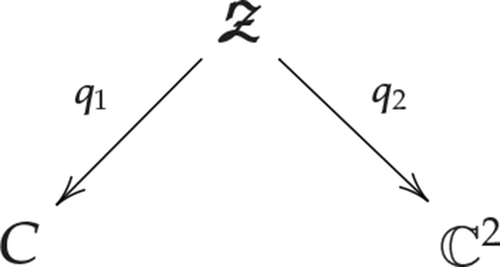

Proof. Represent 𝔽0 as a divisor in ℙ2 × ℙ1 via the embedding , [z0, z1]↦[z0, z1, z1]. Let be the surface obtained as the blowup p of a pair of points on the line at infinity ℓ∞ ⊂ ℙ2 (see Section 4.7.). Note that ℓ∞ is disjoint from the image of the line ℓz. Then there is a correspondence diagram

(4.93)

(4.93)

Proposition 4.3. For each fixed (mz, mw) ∈ ℤ2, there is a natural -equivariant bijection between the moduli spaces

Proof. Given [ℰ] ∈ 𝔐N,k(𝔽0), define

Proposition 4.2 shows that an instanton gauge bundle ℰ with trivial asymptotics on 𝔽0 can again be regarded as an element [ℰ] ∈ 𝔐N,k(ℂ2). For fixed mz, mw ∈ ℤ, Proposition 4.3 shows that the counting of torsion-free sheaves in the moduli spaces 𝔐N,k(𝔽0) and coincides. In other words, the number of instantons with fixed nontrivial asymptotics matches the Young tableau count, as the number of sheaves (4.96) is independent of the integers mz, mw. Proposition 4.3 also reproduces the formula [54, Section 4.2.2] for the renormalized volume of Young tableaux (reproduced above for N = 1) as the induced shift in instanton charge in (4.95) of the sheaves (4.96).

Proposition 4.4. The moduli space 𝔐N,k(𝔽0) is a smooth quasiprojective variety of complex dimension 2N k.

Proof. As usual, the trivialization condition at infinity guarantees Gieseker semistability and hence quasi-projectivity, as discussed in Section 4.8. Using the divisor ℓ∞ = ℓz + ℓw of 𝔽0, one constructs the framed moduli space 𝔐N,k(𝔽0) as in [68] with tangent spaces and obstruction spaces given by . By reference [78, Section 5], one has

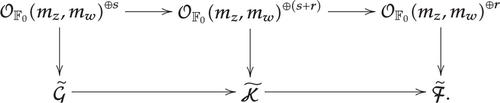

Let be the moduli space of isomorphism classes of pairs , where ℰ is an (mz, mw)-framed torsion-free sheaf on 𝔽0 and is the surjective morphism induced by the framing. Consider the family of pairs consisting of a coherent sheaf ℱ on 𝔽0 together with a homomorphism for some r ∈ ℕ. These pairs define objects of an abelian category cohf(𝔽0) with the obvious morphisms between pairs induced by morphisms of coherent sheaves. Any (mz, mw)-framed torsion-free sheaf ℰ on 𝔽0 clearly defines an object of cohf(𝔽0), with r = N and ch(ℱ) = ch(ℰ).

(4.107)

(4.107)This definition of is equivalent to the usual definition in terms of a twisted Dolbeault complex, and in particular it gives the deformation theory of the moduli space . Furthermore, there is a spectral sequence connecting it to the ordinary Ext-groups .

The line bundle is a projective -module and is therefore flat, whence the tensor product map defined by (4.96) preserves exact sequences such as (4.107). It follows that the tangent spaces are the same for all mz, mw ∈ ℤ. Thus by Proposition 4.4, the moduli spaces are all smooth and diffeomorphic to one another. This is consistent with the fact that stability (either slope stability of torsion-free sheaves [76] or stability of framed modules [20, Section 4.B]) is preserved by twisting with the line bundles .

4.9.2. Universal Sheaves

Proposition 4.5. The Dirac bundle V is a vector bundle of rank k over 𝔐N,k(𝔽0).

Proof. By reference [78, Section 5], one has

4.9.3. Framed Modules on 𝔽0 from Dirac Modules on ℙ1

Theorem 4.6. The isotopical decompositions of the spinor modules over ℙ1, as ℂ*-modules, are given by

Proof. The solutions of the Dirac equation are given by L2-solutions of the differential equations

5. D2-Brane Gauge Theory and Gromov-Witten Invariants

In this final section, we study the reduction of the four-dimensional gauge theories of Section 4 on local curves and examine in detail the example of local ℙ1 which has been extensively described from the point of view of Vafa-Witten theory. We begin with a somewhat heuristic description of how these two-dimensional supersymmetric gauge theories are induced. Then we proceed to a more formal topological field theory formalism which systematically computes topological string amplitudes and Gromov-Witten invariants. Finally, we briefly address wall-crossing issues once again from a physical standpoint.

5.1. q-Deformed Two-Dimensional Yang-Mills Theory

5.2. Topological Field Theory

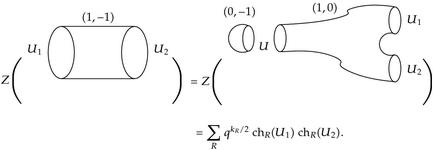

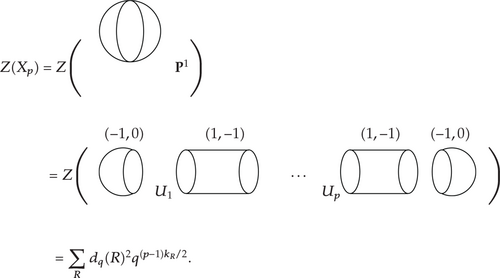

We will now give a more precise definition of this gauge theory using techniques of two-dimensional topological field theory. This formalism can then be used to compute topological string amplitudes. The idea is that the cutting and pasting of base Riemann surfaces is equivalent to the cutting and pasting of the corresponding local Calabi-Yau threefolds, by either adding or cancelling off D-branes corresponding to the boundaries in the topological vertex formalism [84, 86]. The operations of gluing manifolds satisfy all axioms of a two-dimensional topological field theory. By computing the open string topological A-model amplitudes on a few Calabi-Yau manifolds, we then get all others by gluing. In the following we focus on the genus zero case Σ0 = ℙ1 for simplicity and illustrative purposes.

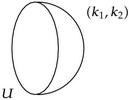

When the base of the fibration is the sphere, we will only need the basic Calabi-Yau cap amplitude corresponding to a disk D, represented symbolically as

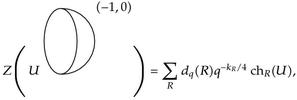

where the levels k1 = e(ℒ1) and k2 = e(ℒ2) label the degrees in H2(D, ∂D) of a pair of line bundles ℒ1 ⊕ ℒ2 → D, and the unitary matrix U labels the holonomy of a gauge connection on ∂D≅S1. Under concatenation the levels add. The basic cap amplitude is defined by

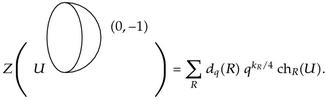

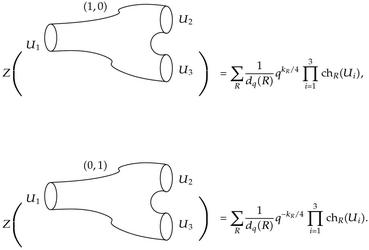

Returning to our computations, we get the annulus (or tube) amplitude by contracting the cap and trinion amplitudes to get

(5.15)

(5.15)For p = 1, the threefold is the resolved conifold, and this formula is a q-deformation of the classical Hurwitz formula counting unramified covers of the Riemann sphere ℙ1.

5.3. Wall-Crossing Formulas

Further analysis of the relationships with 𝒩 = 4 Yang-Mills theory on Cp is studied in [9, 10, 12, 13, 57], where it is observed that the instanton expansions of the two-dimensional and four-dimensional gauge theory partition functions differ by perturbative contributions. These extra factors arise from the noncompactness of the surface Cp. When Cp is the resolution of an Ap,n singularity, its boundary is the three-dimensional Lens space L(p, n) = S3/Γ(p,n). The perturbative factors can then be identified as the partition function of Chern-Simons gauge theory on the boundary and arise as a consequence of the fact that the two-dimensional gauge theory implicitly integrates over all boundary conditions. Once these boundary contributions are stripped, the enumeration of instantons in the two-dimensional and four-dimensional gauge theories coincide [13].

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to thank M. Cirafici, E. Gasparim, A.-K. Kashani-Poor, A. Maciocia, and A. Sinkovics for enjoyable discussions and collaborations on some of the results presented here. This work was supported in part by Grant ST/G000514/1 “String Theory Scotland” from the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council.