Tolerance Intervals in a Heteroscedastic Linear Regression Context with Applications to Aerospace Equipment Surveillance

Abstract

A heteroscedastic linear regression model is developed from plausible assumptions that describe the time evolution of performance metrics for equipment. The inherited motivation for the related weighted least squares analysis of the model is an essential and attractive selling point to engineers with interest in equipment surveillance methodologies. A simple test for the significance of the heteroscedasticity suggested by a data set is derived and a simulation study is used to evaluate the power of the test and compare it with several other applicable tests that were designed under different contexts. Tolerance intervals within the context of the model are derived, thus generalizing well-known tolerance intervals for ordinary least squares regression. Use of the model and its associated analyses is illustrated with an aerospace application where hundreds of electronic components are continuously monitored by an automated system that flags components that are suspected of unusual degradation patterns.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The model and analyses developed in this paper address a problem encountered when analyzing data from service life tests of aerospace hardware packages. Data for as many as 700 performance metrics per part type are automatically stored during surveillance testing and subsequently input into a software program where, up to this point, an ordinary least squares line based on normal-theory has been routinely fit to the data using time-in-service as the explanatory variable. The software program also outputs tolerance intervals based on the ordinary least squares analysis. Engineers monitoring this process are alerted only to those cases where observations in the scatter plot fall outside the tolerance intervals or the tolerance interval crosses a given limit within some specified future time interval (e.g., 60 months). In cases where the alert suggests an increasing accelerated degradation, a proactive corrective action (e.g., part replacement) may be initiated. In cases where the alert suggests less than expected degradation, a cursory investigation to determine if the part is being utilized properly is initiated. Tolerance intervals are often similarly used for monitoring environmental applications [1].

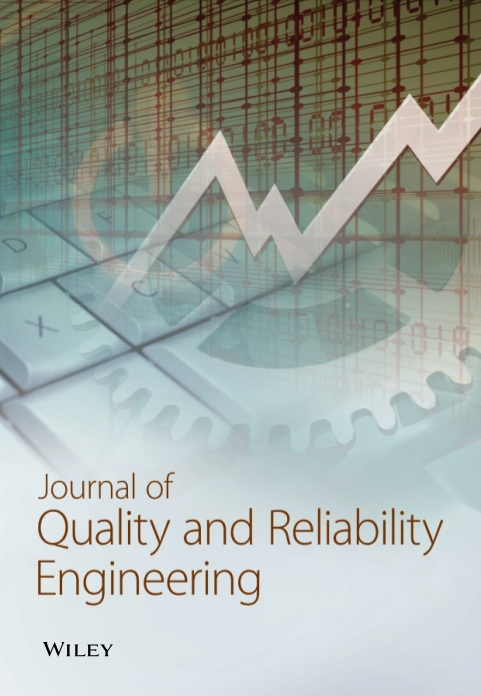

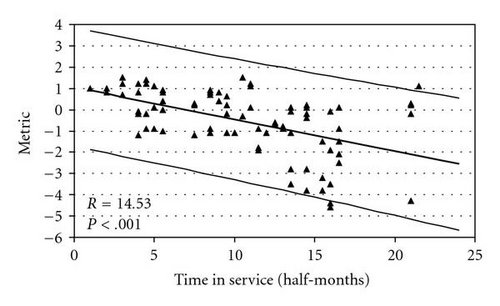

Compared to having engineers individually examine the data from all the combinations of metrics and part types, the automated monitoring and flagging process is quite cost-effective. However, when the variance of the metric increases with time, the tolerance intervals that result from the ordinary least squares analyses fail in the sense that the intervals become too narrow as time increases. Figure 1 illustrates this point, where the 111 observations are the performance metric for one type of part. It is evident from the figure that the random errors associated with the regression model are heteroscedastic. Heteroscedasticity is, of course, not unique to our application. It arises routinely in other applications such as economics, behavioral sciences, social sciences, environmental science, and computer vision. The works in [2–6] provide examples within these disciplines, respectively.

Figure 1 also shows two sets of pointwise 95%-content tolerance intervals constructed at the 90% confidence level. The dashed lines represent the tolerance intervals derived from an ordinary least squares analysis, while the solid lines represent the tolerance intervals derived from an estimated weighted least squares analysis that is described in Section 1.2. The bold line in the figure is the estimated weighted least squares regression line. It is evident in Figure 1 that the ordinary least squares tolerance intervals are inadequate in the sense that they are too wide for small time values and too narrow for large time values. On the other hand, the more pronounced curvature associated with the tolerance intervals derived from the estimated weighted least squares analysis more adequately captures the range of the observations at both ends of the time spectrum.

1.2. Model for Heteroscedasticity

Examination of aerospace data for many part types and many performance metrics led us to propose the following model for heteroscedasticity. Let X(t) denote the metric level at time t for a particular part, and for motivational purposes, assume that the underlying process is a discrete-time valued process (t = 0,1, …). Assume that the initial value of the process is X(0) = β0 + e, where β0 is an unknown constant and e is a normally distributed random variable with zero mean and unknown variance . If the degradation process has both a constant deterministic trend, say β1, and also a random stochastic perturbation, it would follow that X(t) = X(t − 1) + β1 + st, where st is a normally distributed random variable with zero mean and unknown variance . It follows from successive substitutions that , or equivalently, X(t) = β0 + β1t + e + δt, where δt is a normally distributed random variable with zero mean and unknown variance . The model for X(t) is (drifting) Brownian motion, except for the fact that the variance function is displaced from the origin by . In our application, the process X(t) is measured one time on each unit; so the data are a collection of independent observations Yi = Xi(ti), where Xi(t) is the process associated with the ith unit. Thus, we have the model Yi = β0 + β1ti + ei + δi (i = 1, …, n) for the observations.

Equivalently, the model implies that observations are independent and normally distributed with means β0 + β1ti and variances . The fact that a variance component, , is responsible for the heteroscedasticity is somewhat unique to our model since the large literature pertaining to heteroscedasticity models usually assumes variances of the form , where h(·) is an arbitrary function (e.g., a polynomial or the exponential function); see [2, 7] and references therein. While these types of models have seen many successful applications, the lucid interpretation of the heteroscedastic variance function was crucial when eliciting buy-in from our aerospace engineering project stakeholders.

1.3. Tolerance Interval for Heteroscedastic Regression

Defining , the log-likelihood function for based on the observations is

The profile log-likelihood function (e.g., see reference [8]) of ρ is , which can be maximized to find the MLE of ρ, say . The MLEs of β0, β1 and are then are , , and . Unbiasedness of and follows from general results in [9].

A pointwise 100γ%-content tolerance interval with confidence level 100(1 − α)% for a regression line in the context of homoscedastic normal errors was derived in [10]. The following theorem, which is proved in the Appendix A, extends that result to our context.

Theorem 1. If ρ is known, a pointwise 100γ%-content tolerance interval with confidence level 100(1 − α)% for a normal distribution that has mean β0 + β1t and variance is

Proof. See Appendix A.

The pointwise tolerance intervals shown in Figure 1 corresponding to the estimated weighted least squares analysis were drawn from (3) with ρ replaced by its MLE , and with α = 0.1 and γ = 0.95.

1.4. Testing for Heteroscedasticity

Of special importance when analyzing the data for our application is the test of H0 that the data are homoscedastic. If the hypothesis is not rejected, all the pertinent inference can be drawn from an efficient ordinary least squares analyses. On the other hand, rejecting H0 protects a practitioner from the pitfalls of using an inappropriate least squares analysis which include a higher than expected false alert rate. Deriving a test for H0 is particularly interesting from the standpoint that there are alternative tests available in the literature and in subsequent sections in this paper we present a unifying framework for relating alternative tests to each other.

1.5. Overview of Remaining Sections

In Section 2, we position the proposed heteroscedastic model as a special case of a general mixed linear model. We then propose a test of H0 that is motivated by informally combining the root arguments used when deriving locally most powerful tests and score tests. We show that the test statistic has a distribution that only depends on the underlying variance ratio ρ and thus is amenable to a significance test of H0 : ρ = 0. A Monte Carlo algorithm for computing the required critical values is outlined. In Section 3, we relate our proposed test to some common tests for heteroscedasticity, namely, the Breusch and Pagan, White, and likelihood ratio tests. In Section 4, we show additional examples of our test for heteroscedasticity and the use of tolerance intervals within the context of aerospace engineering case study. We also report results of a simulation study that examined the power of all the tests that are discussed in this paper. We close the paper with a short summary in Section 5.

2. Proposed Test for Heteroscedasticity

The heteroscedastic regression model developed in Section 1 is a special case of a more general mixed linear model defined by

We begin the derivation of our proposed test for heteroscedasticity by writing the log-likelihood of the general mixed linear model, based on , as follows:

The distribution of r is and by the nature of R it is clear that its distribution only depends on ρ. A simple approach for finding critical values to test H0 is to simulate r vectors from an MVNn(0, I − PX), compute the corresponding values of R from (8), and estimate the critical value from the resulting empirical distribution (edf) function of R values. Denoting the upper-α percentile of the edf by Ra, the R test rejects H0 if R > Rα. We emphasize the computational simplicity of R, and the ease in which critical values can be obtained. It is also possible to reexpress the null distribution of (8) as a ratio of quadratic forms in independent standard normal random variables and then the saddlepoint approximation described by [11] can be employed to approximate the P-value associated with the test.

A locally most powerful invariant (LMPI) test of H0 was derived in [12–14]. The derivation of this test is sketched in Appendix B. It can be seen there that the complexity of computing LMPI test is nontrivial. The key result in Appendix B is the demonstration that the LMPI test and the R test are equivalent under the general mixed linear model. The practical significance of this finding is that the computation of the LMPI test, as originally proposed, involves a complicated eigenvalue and eigenvector analysis, whereas computing the equivalent form R test only requires fitting the model with ordinary least squares tools. To characterize this computational contrast another way, the computations associated with the equivalent form R test can be done with software as simple as Excel, whereas the computations associated with the originally proposed form LMPI test will require a rich matrix processing software package.

From a conceptual perspective, the equivalence between the LMPI test and the R test is interesting in the sense that the original complicated derivation of the LMPI test can be replaced by the simpler derivation of the R test. In addition, the demonstrated equivalence also provides further motivation for a procedure introduced in [15] where a test statistic is derived by replacing nuisance parameters in the locally most powerful test statistic by their conditional MLEs. Results in [15] show this procedure produces an asymptotically uniformly most powerful test. Our equivalence finding shows that when we used this approach to derive the R test, in a finite sample context, we arrive at a locally most powerful invariant test.

3. Other Tests for Heteroscedasticity

The Breusch and Pagan test for homogeneity is a partial score test derived for a general setting where the observations are independent and normally distributed with means and variances , where is a p × 1 vector of known covariates, β is a p × 1 vector of unknown parameters, is a q × 1 vector of known covariates (whose components may or may not overlap with the components of ), ξ is a q × 1 vector of unknown parameters, and h(·) is an arbitrary function that is only assumed to possess a first derivative. By setting the first component of to unity, a test of is a test of heteroscedasticity. The Breusch and Pagan test [16] is the partial score test of . For application to our problem, we have , and and the test statistic simplifies to

The White test [17] is positioned to be robust to the normality assumption. For our application, the statistic can be obtained by first computing the vector of squared residuals, say u where , and then computing the test statistic as

The log-likelihood function for the general mixed linear model was given in (5) and computation of the MLE of and the conditional MLE of was discussed in Section 2. It follows that the likelihood ratio test statistic is

4. Application to Aerospace Case Study

4.1. Illustrative Examples

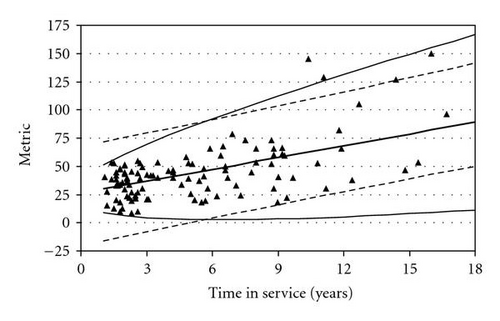

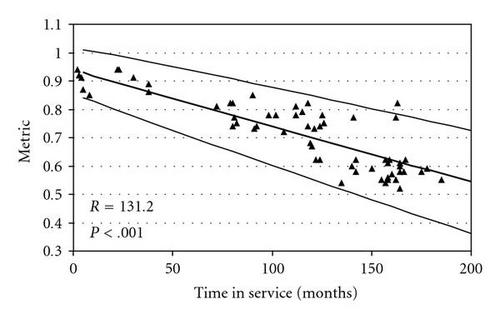

Figure 1 was used in Section 1 as illustrative of a data set that exhibits heteroscedasticity. Figure 2 shows a second illustrative data set (109 observations) which does not exhibit evidence of heteroscedasticity. As in Figure 1, two sets of pointwise 95%-content tolerance intervals constructed at the 90% confidence level are shown corresponding to an ordinary least squares analysis and the estimated weighted least squares analysis described in Section 1.2. In contrast to Figure 1, the two sets of tolerance intervals are nearly identical.

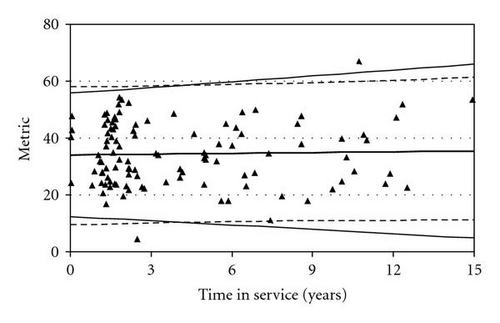

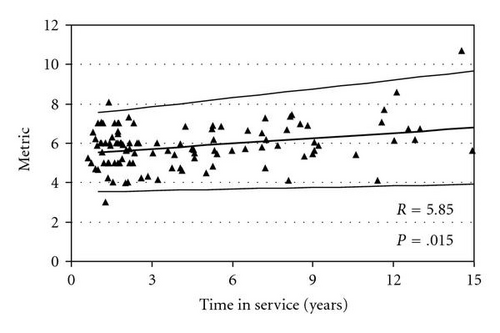

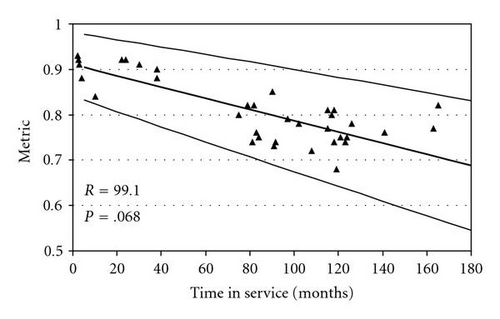

Table 1 shows the computed test statistics R, BP, W, and LRT for the two data sets shown in Figures 1 and 2, along with their P-values for testing H0 : ρ = 0. The tests all agree that heteroscedasticity appears to exist in Data Set 1 but not in Data Set 2. We note that of all the tests considered, R is by far the simplest to compute with BP and W only slightly more complicated. As described in the introduction, our application context has hundreds of metrics that need to be monitored with this type of analysis methodology. Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6 provide four additional illustrative examples, including the computed R statistic and associated P-value for H0 : ρ = 0. There is evidence of heteroscedasticity in all four of these data sets.

| Test | Data Set | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Set 1 | Data Set 2 | |||

| Statistic | P-value | Statistic | P-value | |

| R | 8.92 | <.001 | 4.83 | .062 |

| BP | 52.1 | <.001 | 2.05 | .15 |

| W | 26.6 | <.001 | 3.29 | .17 |

| LRT | 34.8 | <.001 | 1.59 | .10 |

4.2. Power Comparison of Alternative Tests

It is easy to show that the distributions of the R, BP, W, and LRT test statistics depend only on ρ. It follows that the power functions (i.e., the probability of rejecting H0 : ρ = 0 as function of ρ) of the tests can be evaluated using simulated data sets from the mixed model in (3) using the parameters . We implemented our simulation study using the S-Plus package. For each simulated data set, each of the test statistics can be evaluated and compared to their respective critical values corresponding to nominal size α significance tests. The power of the tests is estimated by the fraction of data sets for which they reject H0.

Column 2 of Table 2 shows the estimated power of the 10% nominal size R test based on this procedure for ρ ∈ [0,0.25], using 5000 simulated data sets and the same set of values associated with Data Set 1, which is shown in Figure 1. Columns 3–5 of Table 2 give the ratio of the power for the LRT, BP, and W tests, relative to the R test. The results show that the R test and the LRT have nearly identical power, though the R test has slightly better power for small ρ. The R test has uniformly better power than BP and W tests. A somewhat surprising observation is the pronounced dominance of R with respect to BP and W, which are perhaps the two most widely known tests in the economics literature. Table 3 shows similar power comparisons using the associated with Data Set 2, that is shown in Figure 2, and the conclusions are consistent with those drawn from Table 2.

| ρ | Power of R Test | Ratio of Power Relative to R Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRT | BP | W | ||

| 0.00 | 0.100 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| 0.01 | 0.155 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 0.02 | 0.206 | 0.97 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| 0.03 | 0.278 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| 0.04 | 0.344 | 0.96 | 0.66 | 0.60 |

| 0.05 | 0.392 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| 0.06 | 0.443 | 1.02 | 0.68 | 0.67 |

| 0.07 | 0.492 | 1.01 | 0.72 | 0.67 |

| 0.08 | 0.541 | 1.01 | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| 0.09 | 0.584 | 1.01 | 0.77 | 0.71 |

| 0.10 | 0.624 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.70 |

| 0.11 | 0.663 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.73 |

| 0.12 | 0.701 | 1.01 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| 0.13 | 0.719 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| 0.14 | 0.741 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.76 |

| 0.15 | 0.763 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 0.77 |

| 0.16 | 0.783 | 1.02 | 0.84 | 0.78 |

| 0.17 | 0.809 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 0.78 |

| 0.18 | 0.830 | 1.01 | 0.86 | 0.80 |

| 0.19 | 0.830 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| 0.20 | 0.843 | 1.02 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| 0.21 | 0.861 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 0.83 |

| 0.22 | 0.869 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 0.84 |

| 0.23 | 0.875 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.84 |

| 0.24 | 0.884 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| 0.25 | 0.900 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| 0.30 | 0.923 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| 0.35 | 0.943 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| 0.40 | 0.949 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| ρ | Power of R Test | Ratio of Power Relative to R Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRT | BP | W | ||

| 0 | 0.100 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.89 |

| 0.001 | 0.107 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| 0.002 | 0.104 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 0.98 |

| 0.003 | 0.126 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| 0.004 | 0.127 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.81 |

| 0.005 | 0.128 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| 0.006 | 0.134 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.81 |

| 0.007 | 0.146 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| 0.008 | 0.136 | 1.03 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| 0.009 | 0.137 | 1.06 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| 0.010 | 0.148 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.68 |

| 0.011 | 0.152 | 1.01 | 0.72 | 0.78 |

| 0.012 | 0.174 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.68 |

| 0.013 | 0.171 | 0.97 | 0.68 | 0.73 |

| 0.014 | 0.168 | 1.03 | 0.68 | 0.74 |

| 0.015 | 0.183 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.70 |

| 0.016 | 0.189 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 0.67 |

| 0.017 | 0.200 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| 0.018 | 0.204 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.62 |

| 0.019 | 0.205 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| 0.02 | 0.206 | 0.99 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| 0.03 | 0.267 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.61 |

| 0.04 | 0.316 | 1.10 | 0.66 | 0.64 |

| 0.05 | 0.384 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.63 |

| 0.06 | 0.443 | 1.01 | 0.71 | 0.63 |

| 0.07 | 0.496 | 1.02 | 0.74 | 0.64 |

| 0.08 | 0.544 | 1.02 | 0.74 | 0.68 |

| 0.09 | 0.586 | 1.03 | 0.76 | 0.70 |

| 0.10 | 0.639 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| 0.11 | 0.676 | 1.01 | 0.80 | 0.71 |

| 0.12 | 0.700 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 0.72 |

| 0.13 | 0.735 | 1.01 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| 0.14 | 0.756 | 1.02 | 0.84 | 0.77 |

| 0.15 | 0.783 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 0.79 |

| 0.16 | 0.799 | 1.01 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

| 0.17 | 0.828 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| 0.18 | 0.830 | 1.03 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| 0.19 | 0.853 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.83 |

| 0.20 | 0.868 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.84 |

| 0.21 | 0.878 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| 0.22 | 0.887 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 0.86 |

| 0.23 | 0.897 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 0.86 |

| 0.24 | 0.903 | 1.02 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| 0.25 | 0.907 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| 0.30 | 0.935 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| 0.35 | 0.959 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| 0.40 | 0.973 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

5. Summary

Our aerospace case study, which pertains to the time evolution of performance metrics for electronic equipment, motivated the derivation of a model for heteroscedastic regression errors. A test for homoscedasticity was proposed and compared with various other tests that are prevalent in the literature. The proposed R test was shown to be equivalent to an LMPI test associated with a general mixed linear model of which this paper’s heteroscedastic regression model can be regarded as a special case. Aside from what we judge to be a simpler intuitive motivation associated with the R test formulation, it has the practical benefit of being much simpler to compute than the formula that results from the classical LMPI derivation. The power of the R test was compared to some popular alternative tests, and only the considerably more difficult to compute likelihood ratio test has power that is comparable to the R test. We extended the classical application of tolerance intervals for regression to our heteroscedastic case and illustrated their use with six data sets from our aerospace case study.

Appendices

A. Tolerance Intervals for Heteroscedastic Model

Using observations that follow a simple linear regression model Yi = β0 + β1ti + ei, (i = 1, …, n), Wallis [10] derived a tolerance interval for a normal distribution that has mean β0 + β1t and variance . The Wallis interval easily extends to the more general case where the observations are of the form Yi = β0t0i + β1t1i + ei, where the are not necessarily equal to unity. In particular, a 100(1 − α)% tolerance interval with content γ for the normal distribution with mean β0t0 + β1t1 (where t0 and t1 are arbitrary) and variance is

The heteroscedastic regression model described in Section 1.2 generalizes the problem solved by Wallis by having independent and normally distributed with zero means and variances equal to , where ρ is a new parameter. The derivation in this Appendix is for the case where ρ is known so that the observations can equivalently be expressed as

Referring back to Section 1.2, it is easily seen that = and = . For the particular choice (t0, t1) = , it can also be shown that N(ρ) = (1 + ρt)/[(1, t)[X′Ω−1(ρ)X] −1(1,t)′] and (A.4) becomes

B. Equivalence of R Test and LMPI Test

Following [19], where PXZ = [X : Z]([X:Z]′[X : Z]) −1[X:Z]′, an appropriate ANOVA table for the mixed model is based on the sum-of-squares decomposition y′y = y′PXy + y′(PXZ − PX)y + y′(I − PXZ)y. The first two terms on the right-hand-side of this decomposition, which we denote as Sβ and Ss, respectively, correspond to fitting the fixed-effects first and then fitting the random-effects after the fixed-effects. The final term, denoted as Se, corresponds to the residual error sum-of-squares. It can be shown that the degrees of freedom associated with these three quadratic forms are p, r = rank (X : Z) − rank (X) and f = n − rank (X : Z), respectively.

Let the nonzero eigenvalues of C = Z′(I − PX)Z be denoted by Δ1 ≤ Δ2 ≤ ⋯≤Δr, and define D = diag (Δi). Let d denote the number of distinct eigenvalues of C, and denote their values by and their multiplicities by . Define Q to be the m × r matrix of orthornormal eigenvectors corresponding to the . Finally, let q = Z′(I − PX)y and define to be a solution to . The following results are proved in [19].

- (a)

has a

- (b)

is independent of Se.

- (c)

For (note that the cardinality of Ji is ri) and , Ss(i) are independent with and .

It is shown in [12] that the locally most powerful invariant test statistic for testing H0 is

To prove the equivalence of the LMPI test based on (B.1) and the R test based on (8), we first note that Se + Ss = y′(I − PXZ)y + y′(PXZ − PX)y = y′(I − PX)y = r′r, which establishes the denominator of the two test statistics coincide. Next, we observe that the numerator of LMPI test statistic, , can be reexpressed as . Since C = QDQ′ implies C2 = QD2Q′, we have t′Dt = = q′q = y′(I − PX)ZZ′(I − PX)y = r′ZZ′r, which establishes that the numerators of the two statistics are also identical.