Oral glucocorticoid pulse therapy for induction of treatment of canine pemphigus foliaceus – a comparative study

Abstract

enBackground

The management of canine pemphigus foliaceus (PF) often requires long-term immunosuppressive treatment that is often associated with unacceptable adverse effects. High-dose glucocorticoid pulse therapy, an alternative protocole used for pemphigus in people, has been shown to provide rapid improvement in dogs with pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris.

Objectives

To further identify the benefit of pulse therapy for management of canine PF, we compared the outcomes of oral glucocorticoid pulse and traditional therapies during the first 3 months of disease management.

Animals

Dogs were allocated based on their oral glucocorticoid regimen during the first 12 weeks of PF management into the ‘traditional’ (20 dogs) or the ‘pulse’ (18 dogs) treatment groups.

Results

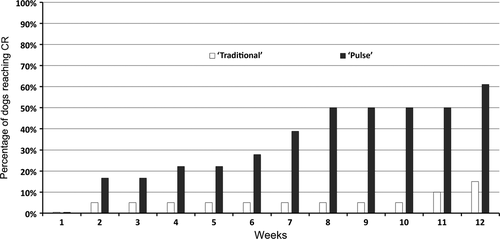

The proportion of dogs achieving complete remission (CR) during the first 12 weeks of treatment was significantly higher for the ‘pulse’ (61%) than for the ‘traditional’ group (15%; P = 0.0063). The maximal oral glucocorticoid dosage given to dogs from the ‘traditional’ group was significantly higher (median: 3.2 mg/kg) than that given between pulses to dogs from the other group (median: 1.1 mg/kg; P < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between groups in the time needed to achieve CR, the proportion of dogs requiring adjuvant immunosuppressive treatment or in the proportion of dogs experiencing severe adverse drug reactions.

Conclusions and clinical importance

These results suggest several benefits associated with oral glucocorticoid pulse therapy, such as a higher proportion of dogs achieving CR during the first 3 months, a lower average maximal oral glucocorticoid dosage given between pulses and minimal adverse drug events.

Résumé

frContexte

La gestion du pemphigus foliacé canin (PF) nécessite souvent un traitement immunosuppressif de longue durée, souvent associé à des effets indésirables inacceptables. Un traitement pulsé avec de hautes doses de corticoïdes, un protocole alternatif utilisé pour le pemphigus chez l'homme, a montré son efficacité rapide chez les chiens atteints de pemphigus foliacé ou vulgaire.

Objectifs

Pour mieux identifier les bénéfices d'une thérapie pulsée pour la gestion du PF canin, nous comparons les résultats d'une corticothérapie orale pulsée et des traitements traditionnels au cours des 3 premiers mois de la maladie.

Sujets

Les chiens ont été alloués en fonction du régime de corticoïdes oraux au cours des 12 semaines de la gestion de leur PF dans les groupes de traitement « traditionnel » (20 chiens) ou pulsé (18 chiens).

Résultats

La proportion de chiens présentant une rémission complète (CR) au cours des 12 premières semaines de traitement était significativement plus élevé pour le groupe «pulsé » (61%) que pour le groupe « traditionnel » (15%; P = .0063). La dose orale maximale de corticoïdes donnée aux chiens du groupe « traditionnel » était significativement plus élevée (médiane: 3.2 mg/kg) que celle donnée entre les pulses aux chiens de l'autre groupe (médiane: 1.1 mg/kg; P < 0.0001). Il n'y avait aucune différence significative entre les groupes dans le temps nécessaire à l'atteinte d'une complète rémission, dans la proportion de chiens nécessitant un traitement immunosuppresseur adjuvant ou pour la proportion de chiens présentant des réactions indésirables sévères.

Conclusions et importance clinique

Ces résultats suggèrent plusieurs bénéfices liés à un traitement corticoïde oral pulsé, tel que la plus haute proportion de chiens présentant une rémission complète au cours des 3 premiers mois, une dose orale de corticoïdes maximale plus faible donnée entre les traitements et les effets indésirables faibles.

Resumen

esIntroducción

el manejo del pénfigo foliáceo canino (PF) a menudo requiere la utilización un tratamiento inmunosupresor a largo plazo que con frecuencia se asocia con efectos adversos inaceptables. La terapia de pulso de glucocorticoides en altas dosis, un protocolo alternativo utilizado para tratamiento de pénfigo en personas, ha demostrado proporcionar rápida mejora en perros con pénfigo foliáceo y vulgaris.

Objetivos

identificar los beneficios de la terapia en pulso para el manejo del pénfigo foliáceo canino, y comparar los resultados con pulso de glucocorticoides por vía oral y las terapias tradicionales durante los tres primeros meses de tratamiento de la enfermedad.

Animales

los perros fueron asignados en base al régimen de terapia oral con corticoides durante las primeras 12 semanas del tratamiento de PF en grupo tradicional (20 perros) y grupo de pulso (18 perros)

Resultados

la proporción de perros que presentaron remisión completa (CR) durante las primeras semanas de tratamiento fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de pulso (61%) que en el grupo tradicional (15%; P = 0,0063). La máxima dosis oral de glucocorticoides administrada a perros en el grupo tradicional fue significativamente mayor (mediana: 3,2 mg/kg) que la administrada entre pulsos a perros del otro grupo (mediana: 1,1 mg/kg; P < 0,0001). No hubo diferencia significativa entre los grupos en el tiempo necesario para obtener remisión completa, la proporción de perros necesitando tratamiento inmunosupresor adyuvante, ni la proporción de perros experimentando reacciones adversas severas.

Conclusiones e importancia clínica

estos resultados sugieren varios beneficiados con la terapia oral con glucocorticoides en pulso, tales como mayor proporción de perros que tienen remisión completa durante los tres primeros meses, un menor nivel de la dosis máxima oral de glucocorticoides entre los pulsos y mínimos efectos adversos.

Zusammenfassung

deHintergrund

Das Management des Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) des Hundes benötigt oft eine langfristige immunsuppressive Therapie, die oft mit unakzeptablen Nebenwirkungen einhergeht. Es konnte gezeigt werden, dass eine hochdosierte Glucokortikoidpulstherapie, ein alternatives Behandlungsprotokoll für Pemphigus beim Menschen, zu einer raschen Verbesserung bei Hunden mit Pemphigus foliaceus und vulgaris führte.

Ziele

Zur weiteren Abklärung der Pluspunkte eine Pulstherapie beim Management des caninen PF verglichen wir die Therapieergebnisse einer oralen Glucokortikoidpulstherapie sowie traditioneller Therapien während der ersten 3 Monate des Krankheitsmanagements.

Tiere

Die Hunde wurden aufgrund ihres oralen Glucokortikoidbehandlungsregimes während der ersten 12 Wochen ihres PF Managements der „traditionellen” (20 Hunde) oder der „Puls” (18 Hunde) Gruppe zugeteilt.

Ergebnisse

Der Anteil der Hunde, welche während der ersten 12 Wochen der Behandlung komplett ausheilten (CR) war in der „Puls” (61%) Gruppe wesentlich höher als in der „traditionellen” Gruppe (15%; P=.0063). Die maximale orale Glucokortikoiddosis, die den Hunden der „traditionellen” Gruppe gegeben wurde, war signifikant höher (median: 3,2mg/kg) als jene, die den Hunden zwischen dem Puls aus der anderen Gruppe gegeben wurde (median: 1,1mg/kg; P<0,0001). Es bestand zwischen den Gruppen kein signifikanter Unterschied in der benötigten Zeit bis zur erreichten Remission, in der Proportion der Hunde, die zusätzliche immunsuppressive Therapie benötigten oder in der Proportion der Hunde, die starke Nebenwirkungen auf die Medikamente zeigten.

Schlussfolgerungen und klinische Bedeutung

Diese Ergebnisse zeigten einige Vorteile der oralen Glucokortikoidtherapie auf, wie zum Beispiel ein höherer Anteil der Hunde, der CR während der ersten 3 Monate erzielte, eine niedrigere durchschnittliche maximale orale Glucokortikoiddosis, die zwischen dem Puls gegeben wurde und minimale Medikamentennebenwirkungen.

Abstract

jaAbstract

zhIntroduction

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is the most common autoimmune skin disease of dogs, and, in most cases, it requires long-term (often life-long) treatment.1, 2 After more than three decades of experience of treating dogs with PF, glucocorticoids remain the most common therapeutic intervention.1-5 Traditionally, the induction dose of prednisone or prednisolone used for canine PF ranges from 2.2 to 6.6 mg/kg/day.6 An attempt to reduce this dose is made as soon as the disease undergoes remission, which can often take several months. Indeed, the average time to complete remission (CR) of skin lesions in dogs reported in the largest canine PF case series was 9 months (range 1–36 months). Surprisingly, the addition of azathioprine as adjuvant therapy did not significantly shorten this time.2 Unfortunately, as the treatment with glucocorticoids is often prolonged, numerous adverse effects usually develop, many of which are intolerable for owners and lead to requests for euthanasia.1, 2, 5 In two series, between 2 and 3% of dogs treated for PF were euthanized because of unacceptable treatment adverse effects.2, 5 Therefore, there is a need for alternative treatment protocols that would provide rapid remission and, potentially, reduce the need for prolonged courses of glucocorticoids at high dosages.

Pulse therapy with high-dose glucocorticoids for human pemphigus vulgaris (PV) was introduced more than three decades ago as a means to provide rapid disease control, which would then allow for earlier dose reduction of glucocorticoids and/or adjunctive immunosuppressive drugs.7-9 Originally, pulse therapy was defined as intermittent intravenous injections of very high doses of glucocorticoids (10–20 mg/kg of methylprednisolone or 2–5 mg/kg of dexamethasone) over a short period of time, with or without adjuvant drugs such as cyclophosphamide or azathioprine. While most open studies reported the exceptional benefits of pulse therapy, such as a high rate and a rapid onset of CR, as well as a low rate of adverse effects in patients with PV,9 a randomized double-blinded controlled trial did not identify any outcome benefits when compared to conventional PV therapy.10

The evidence of efficacy of glucocorticoid pulse therapy is limited in veterinary dermatology. An open study reported a dramatic and rapid improvement (time not specified) of skin lesions in one dog with PV and three with PF after a single pulse of intravenous methylprednisolone at 11 mg/kg for three consecutive days.11 Adverse effects associated with this pulse therapy were not observed in any of the four dogs.11 Although only reported in abstract form, a randomized, controlled trial of 20 dogs with PF did not suggest any additional benefits of a single intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg for three consecutive days) when compared to the outcomes achieved using conventional therapy.12

Our objectives were to compare the therapeutic outcomes of oral glucocorticoid pulses and traditional therapy during the first 3 months of disease management (i.e. induction phase). To reduce the relative imprecision associated with any retrospective study, only outcomes that were clearly identifiable were reported. These included, for each treatment group, the number of dogs achieving CR, the time to CR, the number of dogs requiring adjuvant immunosuppressive therapy and the number of dogs experiencing severe adverse drug reactions.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

For this study we examined medical records of all dogs diagnosed with PF at North Carolina State University's (NCSU) Veterinary Hospital's Dermatology Service between October 1994 and December 2013. Medical record data from 1994 to 2003 were examined retrospectively, whereas data from dogs with PF seen after January 2004 were entered in a prospective fashion.

All dogs considered for inclusion in this cohort study had been diagnosed with a ‘classic’ phenotype of PF. The dogs exhibited – a minima – erosions and crusts, with or without pustules, located predominantly on the face in a bilateral and symmetrical fashion; lesions could be present on other body locations (generalized phenotype), but the presence of a ‘classic’ facial involvement was required. In all dogs there was microscopic demonstration of acantholytic keratinocytes with no clinical or microscopic signs of skin infection (i.e. intracellular cocci in neutrophils), nor interface dermatitis at the site of active lesions. Together with the clinical phenotype, the lack of these histological features permitted the exclusion of other acantholytic diseases such as pyoderma due to exfoliative toxin-producing staphylococci and pustular dermatophytosis.6 The demonstration of skin-fixed or circulating anti-keratinocyte autoantibodies and/or elevated circulating anti-desmocollin-1 antibodies was not required for inclusion of the cases herein.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded from this series dogs that either: (i) had received immunosuppressive regimens prior to coming to NCSU; or (ii) had not been treated with oral glucocorticoids by a veterinarian at NCSU; or (iii) had been prescribed an adjuvant immunosuppressive drug at the onset of PF treatment induction; or (iv) had not been followed up for at least 12 weeks by one of the veterinarians from NCSU; or (v) had owners who had not been compliant with treatment recommendations. Finally, we excluded dogs that had received a combination of ‘traditional’ and ‘pulse’ protocols of oral glucocorticoids during the first trimester of treatment induction.

Treatment groups

Dogs that satisfied inclusion criteria were divided into two groups based on their oral glucocorticoid regimen during the first 12 weeks of PF treatment induction:

‘Traditional’ group: traditional oral glucocorticoid therapy

These dogs received oral glucocorticoids (prednisone or prednisolone) in a standard-of-care protocol traditionally employed for treatment of canine PF (i.e. inducing treatment with a targeted dosage equal or greater than 2 mg/kg/day, this dosage being continued until lesion remission; the doses of glucocorticoid being then reduced as needed to maintain the complete remission of signs, and aiming, in the long term, for intermittent daily therapy).6

‘Pulse’ group: oral glucocorticoid pulse therapy

In this group, dogs received at least one pulse of oral glucocorticoids, each pulse consisting of prednisone or prednisolone at 10 mg/kg once daily for three consecutive days, followed by a reduced dosage of the glucocorticoid (target: <2 mg/kg/day). Pulses could be repeated, at the discretion of the veterinarian, if new lesions continued to appear in spite of the lower doses of glucocorticoids given between 3-day pulses; pulses were not to be repeated more than once weekly. The progress of each dog was evaluated on a weekly basis (weekly recheck visit or direct communication with the referring veterinarian and/or owner) until CR was achieved.

If dogs from either group were also treated with a nicotinamide (niacinamide)–tetracycline combination, topical glucocorticoids or oral antibiotics during the first 12 weeks of PF treatment induction, such interventions were recorded.

If, after at least 4 weeks of oral glucocorticoid therapy (using either ‘traditional’ or ‘pulse’ protocols), new pustules or erosive lesions continued to appear, the attending veterinarian had the option of adding an adjuvant immunosuppressive drug, such as azathioprine or ciclosporin at dosages normally used for this disease.6 This use of adjuvant therapy was also recorded.

Main outcome measures

Initially, to ensure that both groups of dogs were similar, the age of disease onset and the percentage of subjects with exclusively facial versus generalized phenotype were compared among treatment groups. Due to the relative imprecision of reviewing records retrospectively, we then selected outcome measures that were clearly identifiable from the clinical visit summaries and client communication records of each dog included in either group:

- Number (percentage) of dogs achieving CR during the first 12 weeks of PF treatment induction. Complete remission was defined as a complete disappearance of all lesions directly attributed to PF (e.g. pustules, erosions and crusts covering erosions).

- Time to CR, defined as the time (in weeks) needed to achieve CR, if so attained, during the first 12 weeks of PF treatment induction.

- Number (percentage) of dogs needing adjuvant immunosuppressive therapy, the latter being defined as the addition of azathioprine or ciclosporin (or any other drug with similar immunosuppressive properties).

- Number (percentage) of dogs treated with antibiotics, topical glucocorticoids or niacinamide with tetracycline, as these interventions have been shown, or are perceived, to have an influence on outcome.

- Number (percentage) of dogs experiencing severe adverse drug effects (ADEs), defined as death or ADEs requiring medical attention/treatment. Adverse drug events that are expected with glucocorticoid therapy (e.g. polyuria, polydipsia, etc.) were not included in this category.

Statistical analyses

The comparison of categorical parameters between groups was done using two-sided Fisher's exact tests; that of continuous values was made with a Mann–Whitney U-test. The threshold of significance was set at P = 0.05. Statistical analyses were done using Prism 5 (Graphpad software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Study subjects

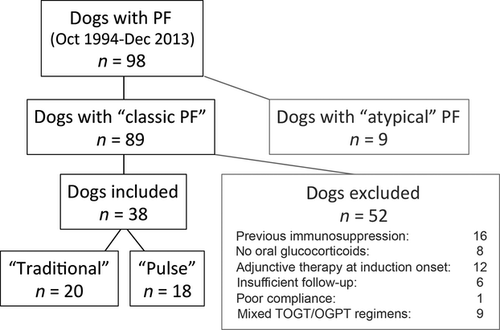

Details on the allocation of dogs with PF to the ‘traditional’ and the ‘pulse’ groups can be found in the flow chart presented as Figure 1. These groups were not significantly different in regards to age of the dogs at the time of disease onset, or the proportion of dogs with a generalized rather than facially restricted disease (data not shown).

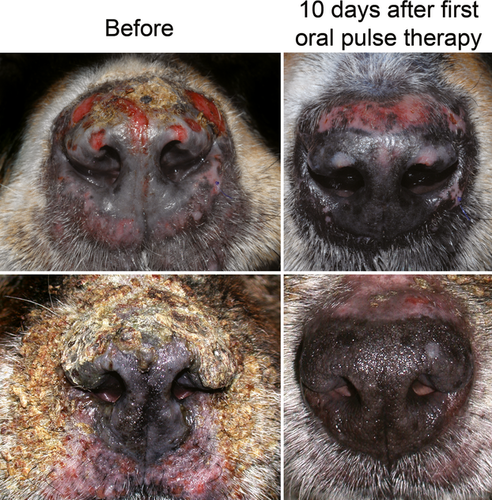

The main outcome measures for each group can be found in Table 1. The proportion of dogs achieving CR during the first 12 weeks of PF treatment induction was significantly (P = 0.0063) higher in dogs from the ‘pulse’ group (61%) compared to those from the ‘traditional’ group (15%). The number needed to treat (NNT) for CR during pulse compared to traditional therapy (i.e. the inverse of the difference between percentages of CR, rounded upward) was calculated at three, a low number (i.e. three dogs would need to be treated with pulse therapy to get an additional CR compared to traditional protocols). The proportion of dogs reaching CR every week is depicted in a cumulative graph in Figure 2, and two examples of rapid improvement following the first oral glucocorticoid pulse are shown in Figure 3. The time to CR and the proportion of dogs needing adjuvant immunosuppression during the first 12 weeks of treatment induction were lower in dogs receiving glucocorticoid pulses, but they were not significantly different between groups (Table 1).

| ‘Traditional’ | ‘Pulse’ | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of dogs | 20 | 18 | |

| Number (%) of dogs achieving CR | 3 (15%) | 11 (61%) | 0.0063 |

| Time to CR; median (range) (weeks) | 9.1 (2.0–11.9) | 6.9 (1.7–11.9) | 0.4353 |

| Number (%) of dogs needing adjuvant therapy | 12 (60%) | 7 (39%) | 0.3300 |

| Number (%) of dogs experiencing severe ADEs | 2 (10%) | 2 (11%) | 1.000 |

- CR, complete remission; ADE, adverse drug events.

The mean and/median number of pulses was two (range: 1–4). The maximal oral glucocorticoid dosage given to dogs from the ‘traditional’ group during treatment induction was significantly higher [median 3.2; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.5–3.9 mg/kg] than that given between pulses to dogs from the second group (median 1.1; 95% CI: 1.1–1.7 mg/kg; P < 0.0001).

The percentage of dogs treated with topical glucocorticoids was not significantly different between ‘traditional’ and ‘pulse’ groups (40% versus 67%; P = 0.119). Similarly the percentage of dogs receiving niacinamide and tetracycline in addition to their glucocorticoids was not significantly different between ‘traditional’ and ‘pulse’ groups (20% versus 50%; P = 0.087). There was no significant difference in the prescription of antibiotics during the first 12 weeks of treatment induction in dogs from the ‘traditional’ (40%) and those from the ‘pulse’ group (44%) (P = 1.000).

The number of dogs with severe ADEs was identical in both groups (two dogs each). In the ‘traditional’ group, one dog died suddenly and one developed azathioprine-induced myelosuppression. In the ‘pulse’ group, one dog was euthanized at his owner's request due to the appearance of signs of iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome and one dog developed melena on its fourth pulse. In the ‘traditional’ group, there were no ADEs other that those expected to occur with glucocorticoid therapy (e.g. polyuria/polydipsia, polyphagia, weight gain). In the ‘pulse’ group, however, two dogs (11%) developed transient diarrhoea and two (11%) exhibited transient aggressive behaviour; these ADEs regressed spontaneously at the end of the pulses.

Discussion

The main goal of glucocorticoid pulse therapy in human pemphigus is to achieve a higher rate and speed of disease remission and, potentially, to establish a long-term CR. In this retrospective study, oral glucocorticoid pulse therapy resulted in a significantly higher proportion of dogs achieving CR during the first 3 months than in those using traditional protocols (pulse: 61%, traditional: 15%). Although a large case series of 91 PF-affected dogs reported CR in about 52% of dogs using conventional treatment approaches,2 a direct comparison with our CR data could not be made because the time frame of the reported CRs was not limited to the first 3 months of treatment, as in our study. Results of a randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of a single pulse (three consecutive days) of intravenous methylprednisolone dosed at 10 mg/kg/day, showed no difference in response between groups (pulse dose 67% CR; traditional dose 75% CR). Again, the time frame of the reported CR was not limited to the first 3 months of treatment.12 Moreover, dogs in our study received repeated pulses, whereas dogs in the randomized control trial received only a single pulse at the beginning of their treatment.12

In the present study, the median time to CR in the pulse therapy group was 6.9 weeks. The mean time to CR reported in a randomized control trial was 8.2 weeks.12 In both studies, the time to CR was not significantly different between the pulse and the traditional groups. Furthermore, the median time to CR in both treatment groups in our study was markedly shorter than the median time to CR of 6.5 months previously reported.2 The reason for such differences remains unknown.

Adjuvant immunosuppressive drugs are commonly used for management of canine PF, even though their additional benefit has not been fully confirmed. Indeed, the analysis of treatment outcomes in the largest case series reported to date did not show a statistically significant difference between the numbers of dogs responding to glucocorticoid monotherapy and dogs treated with combination of glucocorticoids and azathioprine.2 In our study, adjuvant immunoregulatory therapy was allowed in dogs in which, after at least 4 weeks of oral glucocorticoid therapy (using either traditional or pulse therapy), new pustules or erosive lesions continued to appear. While the proportion of dogs needing adjuvant immunoregulation was lower in the ‘pulse’ (39%) compared to the ‘traditional’ (60%) group, the difference was not significantly different.

In addition to rapid establishment of remission, a goal of pulse therapy is to reduce the overall amount of glucocorticoids received. While the cumulative dose of glucocorticoids could not be calculated in our study due to its retrospective nature, the average maximal oral glucocorticoid dosage given to dogs from the ‘traditional’ group was significantly higher than that given between pulses to dogs from the ‘pulse’ group. In contrast, recent randomized control trials of glucocorticoid pulse therapy in human PV and canine PF failed to demonstrate any beneficial effect of pulse therapy on the average daily dose of glucocorticoids and/or the cumulative dose of glucocorticoids when compared to traditional therapy.10, 12 Nevertheless, authors of the human PV study reported a positive, but not statistically significant, trend with a lower mean prednisolone dose used to achieve CR in the ‘pulse’ group.10. Finally, we speculate that the lack of added benefit (shorter time to CR, lower total dose of glucocorticoids used) for pulse therapy reported previously for canine PF could be related to the single glucocorticoid pulse given at the beginning of the trial, which is in contrast to the often multiple pulses given to the dogs in our study.12 Similarly, reported protocols for glucocorticoid pulse therapy in humans with pemphigus involve repeated pulses until disease CR is reached.9, 10

Because of the contradictory results regarding the effect of antibiotic therapy on the outcome of canine PF,1, 2 the number of dogs receiving antibiotics concurrently with the immunosuppressive drugs was recorded for each group of dogs in our study. There was no significant difference between groups in the percentage of dogs having received antibiotics during the first 12 weeks of treatment.

Adverse drug effects related to the treatment of dogs with PF are the most common reason for euthanasia.1, 2 Because most ADEs are associated with the long-term use of medium to high dosages of glucocorticoids, the 3-day courses of pulse therapy in our study followed by low maintenance dosages could, potentially, result in fewer ADEs in the long term. In this study, severe ADEs were documented in an equal number of dogs from each group, which was similar to findings reported in the other two pulse studies.11, 12

In contrast to these previous two reports,11, 12 the route of administration of glucocorticoid pulses in our study was not intravenous but oral. A similar approach has been used in people.10 In dogs, the high oral absorption of prednisolone that very rapidly provides an adequate drug concentration (peak plasma concentration within about 1.5 h) fully justifies an oral route for pulse therapy in this species.13 When considering the dose equivalency between individual glucocorticoids and their route of administration reported in people (500 mg of methylprednisolone equals 625 mg of prednisone), it could be hypothesized that the oral dose of prednisone/prednisolone used in our study could have been slightly higher. Interestingly, several controlled comparative dose studies in people did not find significant differences in short-term outcomes induced by different doses of methylprednisolone (1000 mg versus 250 mg, 5 mg/kg versus 10 mg/kg, etc.),14, 15 suggesting that the small difference in our dose might have been clinically irrelevant. Finally, one study suggested that 11-β-hydroxydehydrogenases, an enzyme family responsible for the conversion of prednisone to its active form prednisolone, might get saturated with higher dosages of prednisone.16 This observation raises the question whether glucocorticoids such as prednisolone or dexamethasone might be more suitable for pulse therapy rather than prednisone itself.

The translatability of the results of this study is, to some extent, restricted by its limitations, such as the relatively small number of patients and its retrospective nature. Nonetheless, our results suggest several benefits that could be associated with oral glucocorticoid pulse therapy using the protocol reported herein, such as (i) a higher percentage of dogs achieving CR during the first three months, (ii) a lower average maximal oral glucocorticoid dosage given between pulses, and (iii) minimal ADEs.

Future studies of a prospective design, including more patients and the use of prednisolone rather than prednisone, could provide additional information on the benefit(s) of oral glucocorticoid pulse therapy for management of canine PF.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the clinicians of North Carolina State University's (NCSU) Veterinary Hospital's Dermatology Service who were involved in the treatment of some of the patients included herein, in alphabetical order: Frane Banovic, Hilary A. Jackson, K. Marcy Murphy, Ursula Oberkirchner, Christine Rivierre, Michael A. Rossi and Kathy Tater. The authors would also like to thank Mark Papich for his constructive advice on the pharmacology of glucocorticoids.