Owner perceptions of radiotherapy treatment for veterinary patients with cancer

Abstract

Veterinary clients may have trepidation about treating their pet with radiotherapy because of concerns about radiation side effects or repeated anaesthetics. The purpose of this study is to assess whether owners' attitudes towards veterinary radiotherapy, including concerns over side effects, change during the course of treatment, and whether radiotherapy was perceived to affect pets' quality of life (QOL). A prospective cohort study of clients from 2012 to 2015 was performed. Pets received palliative or definitive radiotherapy for various tumours. Clients completed questionnaires before, during and after radiotherapy. Questions assessed owner preconceptions before treatment, including side effect expectations, actual side effects experienced and overall satisfaction with the process. In addition, at each time point, the owners assessed their pet's QOL using a simple numerical scale. Forty-nine patients were included. After completing treatment, owners were significantly less concerned about potential side effects of radiotherapy (P < 0.001), side effects associated with repeat anaesthetics (P < 0.001), and about radiotherapy in general (P < 0.001). QOL did not show a significant change at any point during or after treatment. Following treatment, 94% reported that the experience was better than expected and 100% supported the use of radiotherapy in pets. This is the first prospective study evaluating client attitudes and satisfaction before and after radiotherapy treatment in pets. The results indicate that radiotherapy is well tolerated, and the anxiety associated with radiotherapy is significantly alleviated after experiencing the process. These results will help veterinarians allay client concerns, and will hopefully lead to an increase in clients pursuing radiotherapy in pets.

1 INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy is an expanding field of veterinary medicine. There has been significant growth in the number of veterinary centres providing radiotherapy in recent years, with one (US) survey finding a 57% increase in the number of facilities providing veterinary radiotherapy between 2001 and 2010,1 as well as increased access to more advanced radiotherapy techniques. When presented as a treatment option, veterinary clients may have trepidation about treating their pet because of concerns about radiation side effects or repeated anaesthetics. Many of these concerns may be unfounded and possibly stem from a lack of experience and understanding of radiotherapy.

Side effects associated with radiotherapy are dependent on the protocol used and the area being treated.2, 3 Definitive intent protocols generally involve using smaller daily fractional doses more frequently (“conventionally fractionated”) and are typically associated with more acute side effects and fewer late radiation side effects. Conversely, palliative protocols involve fewer but larger radiation doses separated temporally, often dosed weekly, (“hypofractionated”) and are less likely to cause acute side effects, but increase the chance of late side effects. Acute radiation side effects occur commonly and predictably using conventionally fractionated protocols and occur in rapidly dividing tissues (skin, mucous membranes, gastrointestinal mucosa, etc).2 They can usually be well managed with symptomatic treatments including oral antibiotics and anti-inflammatory corticosteroids and although severe in some cases, such effects are usually short-lived and rarely leave permanent damage. Late radiation effects are uncommon, occurring in less than 5% of patients.3 They are potentially serious and irreversible and are most commonly associated with hypofractionated protocols. Hypofractionated protocols are generally used in palliative settings where animals have a short predicted survival. Late side effects generally develop 1 to 2 years following radiotherapy in tissues with slow turnover rates (eg, bone, connective tissues, nerves, etc).

In the author's experience, there is still some reluctance to pursue radiotherapy amongst pet owners, perhaps due to prejudices stemming from a lack of understanding of the procedure or from prior experiences with radiotherapy in the human field, which can lead owners to believe the treatment will negatively impact their pet's quality of life (QOL). Even among veterinarians, there is often a lack of understanding about what radiotherapy entails. In a previous survey of referring veterinarians concerning radiotherapy, only 57% had attended education programs for oncology or radiotherapy.4 Veterinarians that had not attended education programs reported significantly less positive views regarding radiotherapy and estimated a significantly lower QOL for patients undergoing radiotherapy. These veterinarians also reported significantly fewer situations where they believed radiotherapy was indicated than veterinarians which had attended oncologic or radiotherapy education programs.4 This suggests that a lack of understanding and education about radiotherapy in pets in both veterinarians and owners could potentially be leading to pets not receiving appropriate treatment.

Assessing QOL in veterinary patients has been discussed in numerous studies.5-9 Traditionally, veterinary studies have inferred the impact of treatment on an animal's QOL from objective measurements of physical side effects. Recently, however, there has been an increase in specifically assessing pet QOL in response to treatments. A 2017 article reviewed QOL measurement in studies with cats or dogs receiving chemotherapy, and identified 11 studies which included QOL measurements as part of the study.10

While there is no widely accepted definition of QOL in veterinary patients, most agree that QOL assessments encompasses a continuum of an animal's physical and mental well-being. As animals are unable to self-report, proxies are needed to assess their QOL. Owners are frequently chosen as proxies as they are invariably the most familiar with the pet, including its normal behaviours and routines. Several studies have assessed the validity of using questionnaires with the owner of the pet acting as a proxy and these found that a simple questionnaire design is a useful tool to assess a pet's QOL.6, 8

Numerous previous studies have assessed owner perceptions and patients' QOL in pets undergoing specific treatments for cancer.4, 11-15 However, only three previous studies have specifically addressed the use of radiotherapy in pets.4, 14, 16 All three studies were retrospective cross-sectional studies using questionnaires or phone interviews completed between 1 month and 8 years after completing radiotherapy. These studies relied on owners' recollections of subjective perceptions and would have been susceptible to response bias. Patient’s QOL was perceived to improve in 60% to 78% of cases in two studies,14, 16 and remains stable/improve in 87% of cases in the third study.4 In these studies, 79% to 96% of clients responded that they would go through the process again. The majority of patients in these surveys received palliative radiotherapy, with one study16 focussing solely on patients receiving palliative radiotherapy. This is likely to positively impact owners' perceptions, as palliative radiotherapy is used to directly reduce morbidity associated with cancer, and so improve the QOL.

No previous studies have assessed the owners' attitudes towards radiotherapy prior to commencing treatment, and all studies have relied on memory to assess how the owners' views had changed after the experience.

The aim of the current study was to assess how clients' attitudes regarding the use of radiotherapy in their pet changed over the course of treatment, using questionnaires completed contemporaneously throughout the treatment process. A secondary aim was to assess how the perceived QOL changed over the course of treatment. Based on our subjective experience, we hypothesized that clients would become less anxious concerning possible complications after they had experienced the process, and that there would be no reduction in the perceived QOL of their pets throughout the process.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval was given by the College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences ethics committee at the University of Glasgow in 2012.

From April 2012 to April 2015, all owners of animals referred to the radiotherapy service at the University of Glasgow Small Animal Hospital were invited to participate in the study if their animal was to be treated with radiotherapy as an outpatient. Questionnaires were completed at time of visit by owners, while waiting for their animal to be treated or at a subsequent recheck appointment. For inclusion, in the final analysis, completion of both the first and final questionnaire and at least one intertreatment questionnaire was required. Patients were assigned a number for the study, and questionnaires were matched by number to blind the attending clinicians to responses.

2.1 Radiotherapy protocols

Radiotherapy was delivered using a Siemens OncorExpressionPlus linear accelerator with multileaf collimator using 6-MV photons or an electron beam of varying energy as determined appropriate in the planning process. A variety of radiation protocols were used depending on the disease being treated and goals of therapy. Palliative-intent radiotherapy was defined as radiotherapy aiming to reduce morbidity associated with the disease, while definitive intent radiotherapy was defined as radiotherapy aiming to achieve a durable complete response.

For microscopic residual disease around superficial surgical scars, radiotherapy fields were manually planned to depth dose, using bolus as appropriate, including a 2- to 3-cm margin surrounding the surgical scar and either a single- or parallel-opposed fields. The field coverage was planned to 95% total dose. For nonsuperficial structures of the head, neck and spine, patients were positioned in dorsal or sternal recumbency using personalized beam directional shell and vacuum cushions to immobilize the head along with larger vacuum cushions and/or radiography cradles as necessary to immobilize the body. Position was verified using megavoltage electronic portal imaging, with alignment to skull or other anatomy prior to each dose of radiotherapy with a 2-mm tolerance. Individualized treatment plans were generated using a 3D conformal computer planning software (Prowess Panther, Prowess Inc, Concord, California, USA) and multiple coplanar beams with multileaf collimator, based on computed tomography (CT) images of affected region (with contrast as necessary to view the lesion), and dosed to isocentre. Gross tumour volume was outlined using CT images and 0.5- to 1-cm margin added for planned treatment/target volume (PTV) depending on tumour location and suspected/confirmed histological type. Radiation dose was conformed to the PTV as precisely as possible, while attempting to exclude normal tissues. Ninety-five percent of the total dose was prescribed to the planning target volume. Variations up to a maximum dose of 107% were considered acceptable.

2.2 Anaesthesia

Anaesthesia was performed by a board certified anaesthetist or anaesthesia resident. Anaesthetics typically lasted 20 to 45 minutes, and animals were discharged once they were able to walk without assistance. Admission to discharge times was typically 60 to 90 minutes.

2.3 Adverse effects

Adverse effects were graded according to the Veterinary Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (VRTOG) radiotherapy side effects guidelines.17 They were treated according to clinician preference, typically with oral anti-inflammatory prednisolone (usually 0.5 mg/kg) and antibiotics.

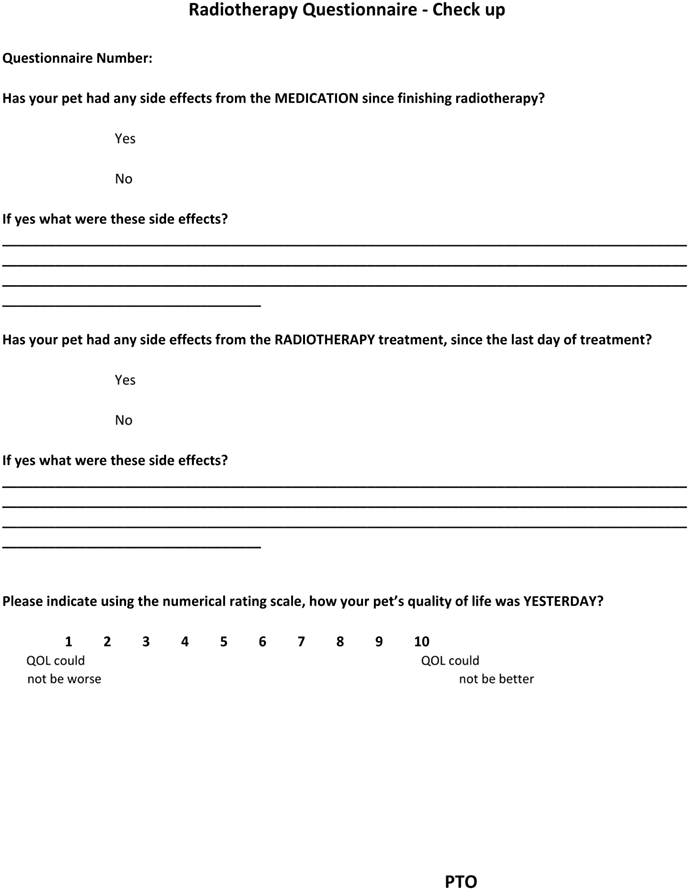

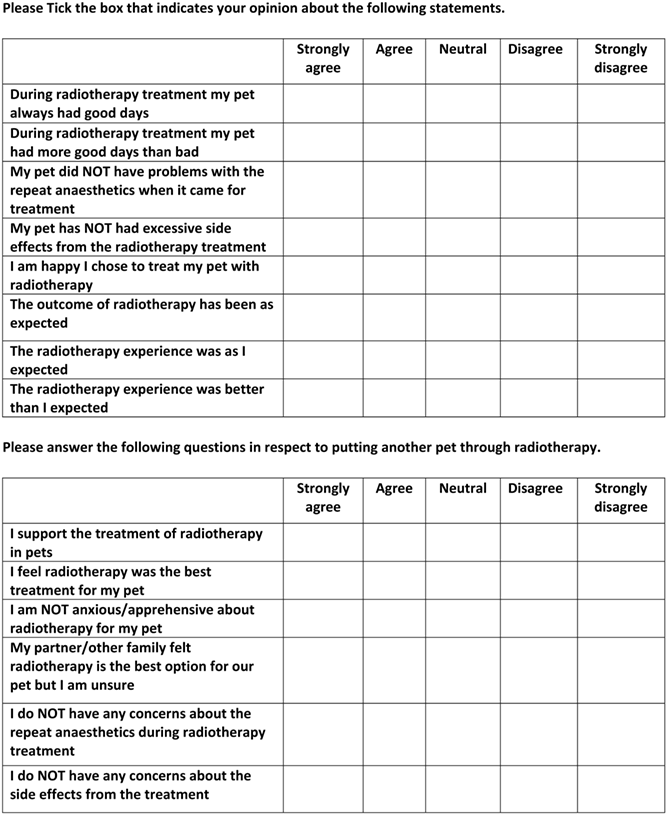

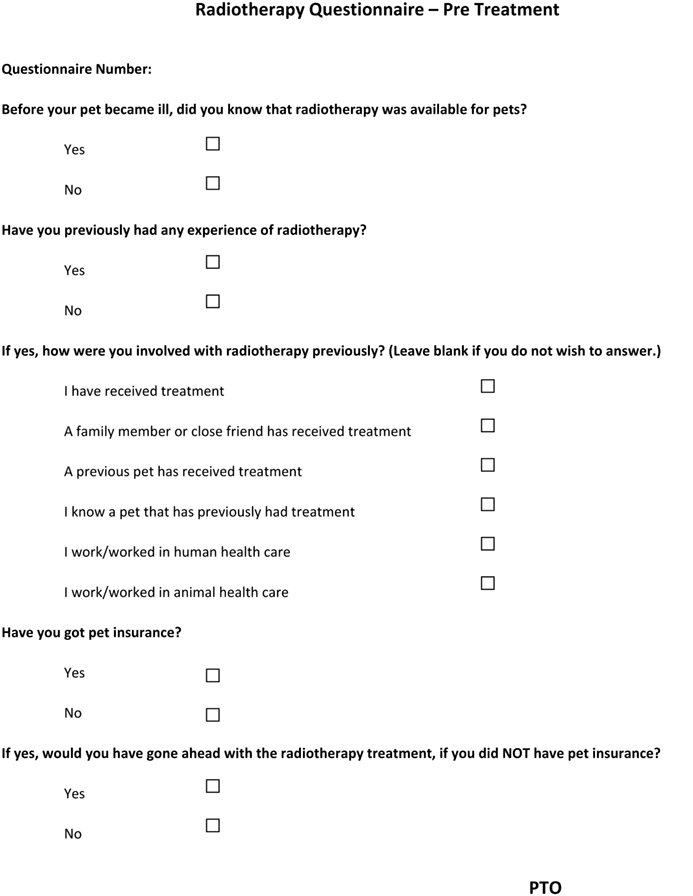

2.4 Questionnaire design

Four questionnaires (Appendix 1) were designed to assess the owner's perceptions of radiotherapy at different points during treatment: prior to commencing radiotherapy (“pre-treatment”); at the time of a treatment during the radiotherapy protocol (“mid-treatment”); at the time of the final radiotherapy treatment (“end-treatment”); and at the standard check-up appointment two to 4 weeks following the final radiotherapy treatment (“post-treatment”). To ensure all answers were scored from one (low impact of radiotherapy) to five (high impact of radiotherapy) in analysis, some negatively phrased questions were included. The questionnaire was trialled on approximately 10 clinicians and nurses within the University of Glasgow Small Animal Hospital prior to commencement, and feedback was used to modify questions to minimize ambiguity. The attending clinicians were blinded to the responses during the radiotherapy treatment; however, the author was unblinded for data analysis in order to correlate responses with case records.

The “pre-treatment” questionnaire was given to the owner at the initial consult when radiotherapy was first recommended for the patient or on the day of the first radiotherapy treatment. This questionnaire had 16 questions which included demographics, perceived QOL, owner's prior knowledge of radiotherapy, insurance status and questions to gauge owner's perceptions and anxiety with regards to radiotherapy.

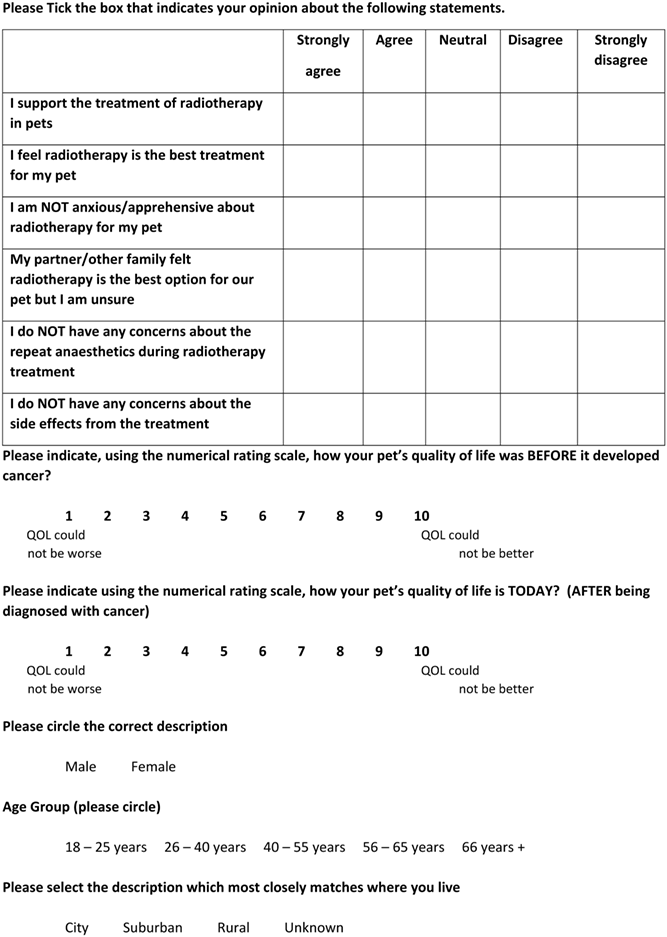

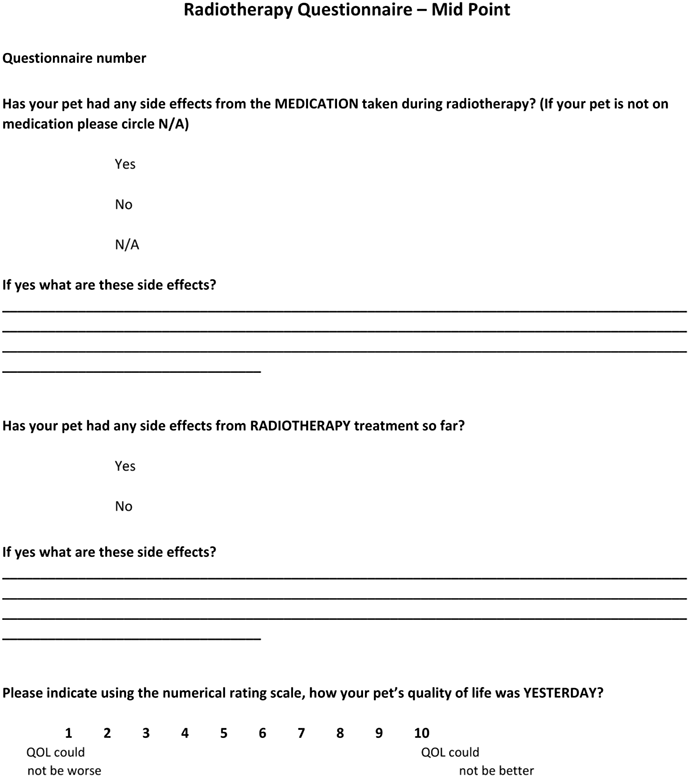

The “mid-treatment” questionnaire was given at the half way point of treatment and had three questions assessing side effects of radiotherapy, side effects of concurrent medications used during radiotherapy and the perceived QOL of the patient at this point. The “end-treatment” questionnaire was the same design as the mid questionnaire but given on the final day of treatment.

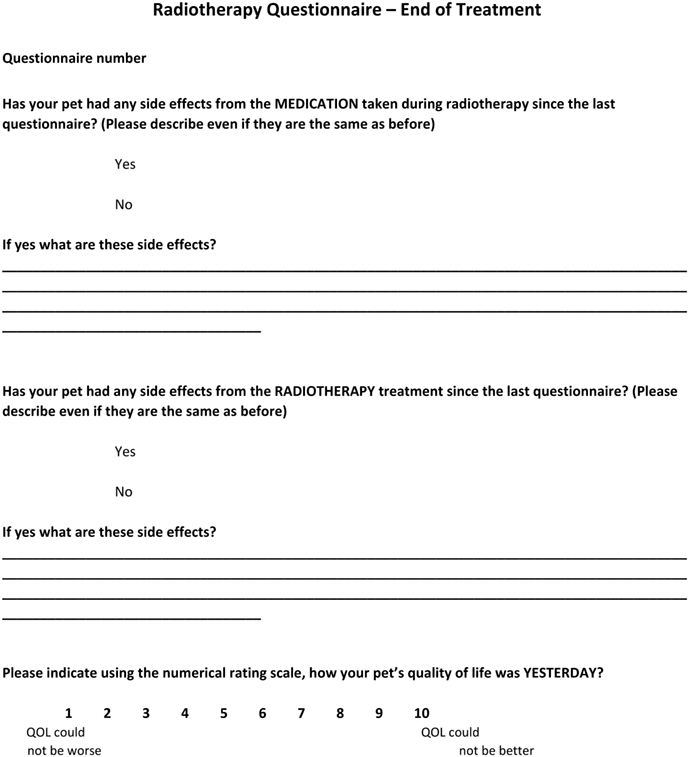

The “post-treatment” questionnaire was given at the check-up appointment between 2 and 4 weeks after the final radiotherapy treatment. This included the questions in the mid and post questionnaires but also included comparable questions to the pre-treatment questionnaire to allow for direct comparison of attitudes before and after undergoing treatment.

QOL was measured using a simple numerical scale from 1 to 10, with one indicating QOL could not be worse and 10 indicating QOL could not be better.

2.5 Statistical analysis

QOL was measured at four time points and was analysed using an analysis of variance with repeated measures test. Discrete statements (ordinal variables) were measured twice, before treatment and at follow-up and were analysed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Responses were assigned a value (1-5) for analysis. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

3 RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-eight patients were referred for radiotherapy during the study period (April 2012-April 2015). Of these, the owners of 96 patients (74%) completed at least one questionnaire. Of 96 patients, 47 (49%) were excluded from the study as they did not complete both the first and last questionnaires. Of 96, 49 (51%) animals met the inclusion criteria; 42 patients had all four questionnaires completed and seven patients had three out of four questionnaires completed. The reason for noncompletion of questionnaires was not recorded.

Of the 128 patients treated in the study period, 17/128 (13%) did not complete the originally prescribed protocol. One of these patients was treated with two courses of radiotherapy during the study period. This patient successfully completed the first protocol, however, did not complete the second protocol because of disease-related morbidity. Of 17, 9 did not complete the protocol because of radiotherapy-unrelated factors (most commonly disease-related morbidity or discovery of metastasis). Of 17, 6 received reduced doses because of acute radiotherapy adverse events. Of 6, 4 received a reduced number of fractions (and reduced overall dose) and 2/6 received a reduced overall dose, however, the planned number of fractions. All six of these patients suffered grade two adverse events (4/6 cutaneous and 2/6 mucous membrane). Of 6 patients, 2 were included in the study. Of 17 patients, 2 stopped treatment because of acute gastrointestinal clinical signs and morbidity suspected to be due to undergoing general anaesthesia.

3.1 Owners

Of 49 patients, 44 (90%) undergoing treatment were insured and so had all or part of the cost of treatment paid for them; 30/44 (68%) reported they would have pursued radiotherapy even if not insured; 8/44 (18%) would not have pursued treatment without insurance and 6/44 (14%) did not submit a response to the question. 15/49 (31%) of owners reported having prior experience with radiotherapy. The vast majority (14/15) had experience from human medicine, with 7/15 having known someone who had been treated with radiotherapy, 6/15 working in human health care and one who had received treatment themselves. Only one owner had prior veterinary radiotherapy experience with a previous pet.

Only 28/49 (57%) of respondents were aware radiotherapy was a treatment option available to pets prior to their pet becoming ill.

3.2 Animals

Forty-seven dogs and two cats were included in the study. Both cats were domestic short hairs. Of the dogs, there were nine cross breeds, eight Labradors, five Staffordshire bull terriers, four golden retrievers, three labradoodles, two border collies and one each of cocker spaniel, Bichon frise, German shepherd dogs, rottweiler, shih tzu, Lhasa apso, saluki, Border terrier, boxer, weimaraner, bearded collie, lurcher, Shetland sheep dog, beagle, spinone and grey hound.

The median age of animals was 8.8 years (range 1.3-14.2 years). There were 22 and 6 neutered and entire females, respectively, and 15 and 6 neutered and entire males, respectively.

3.3 Tumours treated

Tumours treated are listed in Table 1.

| Protocol | Electrons or photons (6 MeV) | Disease treated | Disease location | Adverse event score (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 48Gy over 12 treatments (Monday, Wednesday, Friday) (n = 23) | Photons | FSA (n = 2) | Oral, extremity | 1 | 1 | ||

| Carcinoma (n = 4 | Nasal (n = 4) | 2 | 2 | ||||

| SCC (n = 3) | Tonsillar, oral, nasal | 1 | 2 | ||||

| STS (n = 6) | Extremity (n = 6) | 2 | 4 | ||||

| MCT (n = 1) | Extremity | 1 | |||||

| Chondrosarcoma (n = 1) | Nasal | 1 | |||||

| Sarcoma (n = 2) | Retrobulbar, oral | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Electrons | SCC (n = 1) | Extremity | 1 | ||||

| FSA (n = 1) | Perianal† | 1 | |||||

| STS (n = 1) | Facial† | 1 | |||||

| Pilomatrixoma (n = 1) | Extremity¶ | 1 | |||||

| 40Gy over 8 treatments (Monday, Friday) (n = 17) | Photons | SCC (n = 2) | Pharyngeal, oral | 2 | |||

| MCT (n = 9) | Extremity (n = 8), muzzle | 1ǁ | 5ǁ | 3 | |||

| Infiltrative lipoma (n = 1) | Extremity | 1 | |||||

| STS (n = 1) | Extremity | 1 | |||||

| Electrons | Adenocarcinoma (n = 1) | Anal sac† | 1ǁ | ||||

| Fibrosarcoma (n = 1) | Truncal‡ | 1 | |||||

| MCT (n = 2) | Cutaneous muzzle§, axillary‡ | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 48Gy over 16 treatments (n = 4) | Photons | Glioma (n = 2) | Brain (n = 2) | 2 | |||

| Pituitary adenoma (n = 2) | Brain (n = 2) | 2 | |||||

| 48.6Gy over 18 treatments (n = 1) | Photons | Meningioma (n = 1) | Spinal | 1 | |||

| 39Gy over 11 treatments (n = 1) | Photons | Fibrosarcoma (n = 1) | Oral | 1 | |||

| 36Gy over 4 treatments (weekly) (n = 1) | Photons | Melanoma (n = 1) | Oral | 1 | |||

| 20GY over 5 treatments (n = 1) | Photons | Histiocytic sarcoma (n = 1) | Extremity | 1 | |||

| 32Gy over 8 treatments (n = 1) | Photons | Lymphoma (n = 1) | Brain | 1 | |||

- Abbreviations: FSA, fibrosarcoma; MCT, mast cell tumour; SCC, squamous cell sarcoma; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; TCC, transitional cell carcinoma.

- † = 12 MeV,

- ‡ = 10 MeV,

- § = 8 MeV,

- ¶ = 15 MeV,

- ǁ = denotes a single animal which received concurrent chemotherapy.

3.4 Protocols

Of 49 animals, 47 were treated with a protocol that was considered definitive, while 2/49 animals were treated with a protocol that was considered palliative: a Labrador with oral melanoma treated with 36Gy delivered weekly over four treatments of 9Gy and a Rottweiler with histiocytic sarcoma treated with 20Gy delivered daily over five treatments of 4Gy.

Various protocols were used (Table 1). The most common protocols used were 48Gy divided into 12 fractions of 4Gy (n = 23), 40Gy divided into 8 fractions of 5Gy (n = 17), 48Gy divided into 16 fractions of 3Gy (n = 4) and five other protocols each used in a single animal.

Of 49 protocols, 41 used photons and 8/49 protocols used electrons. Electrons were used when superficial lesions were being treated, and/or radiosensitive organs were located deep to the radiation field. Twenty animals had gross disease and 29 had microscopic disease at the time of radiotherapy.

3.5 Additional treatments

Thirty-one patients had surgery as part of their treatment prior to radiotherapy (including one prophylactic enucleation to avoid ocular radiotherapy side effects). Radiotherapy was commenced 2 to 3 weeks post-surgery. Eleven patients underwent chemotherapy as part of their treatment. Of 9 patients, 4 received intravenous chemotherapy concurrently with radiotherapy (three received vinblastine for mast cell tumour [MCT], one received carboplatin for anal sac adenocarcinoma), 1/9 received metronomic cyclophosphamide prior to radiotherapy and 6/9 received chemotherapy after radiotherapy (including two patients who received toceranib). One patient received a course of melanoma vaccination.

3.6 Adverse effects

Acute adverse events were recorded by the highest grade adverse effects reported at any point during/after treatment (eg, if an animal had grade 1 skin adverse effects and grade 2 mucous membrane adverse effects it was recorded as a grade 2). These are listed in Table 1. Nine animals had no adverse effects, 14 patients had grade 1, 24 had grade 2 and 2 had grade 3. Location of all reported adverse effects was skin (n = 37), mucous membrane (n = 10), ocular (n = 3) and lower gastrointestinal (n = 1).Of the six animals that suffered no acute radiotherapy adverse effects, 5/6 were being treated with conventionally fractionated protocols for brain or spinal neoplasms and one was being treated palliatively with a hypofractionated protocol for histiocytic sarcoma.

Of 49 patients (92%), 45 either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” with the statement “My pet did NOT have problems with repeat anaesthetics.” Only three owners responded “disagree” to the statement and none “strongly disagreed” or were neutral. One owner did not complete this question.

3.7 Questionnaire answers

Six questions present in the “pre-treatment” and “post-treatment” questionnaires were available for analysis. One question was excluded (“My partner/other family felt radiotherapy is the best option for our pet but I am unsure”) as the respondent was not standardized between visits, which made the results difficult to interpret. The remaining five questions were selected from the “pre-treatment” and “post-treatment” questionnaires for analysis (Tables 2 and 3).

| Statement | Median response pre- and post-treatment | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| “I am NOT anxious/apprehensive about radiotherapy for my pet” | Pre-treatment: “neutral” Post-treatment: “Strongly agree” |

0.000 |

| “I do NOT have any concerns about the repeat anaesthetics during radiotherapy treatment” | Pre-treatment: “neutral” Post-treatment: “agree” |

0.000 |

| “I do NOT have any concerns about the side effects from the treatment” | Pre-treatment: “neutral” Post-treatment: “agree” |

0.000 |

| Statement | Median response pre- and post-treatment | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| “I support the treatment of radiotherapy in pets” | Pre-treatment: “strongly agree” Post-treatment: “strongly agree” |

0.317 |

| “I feel radiotherapy is the best treatment for my pet” | Pre-treatment: “strongly agree” Post-treatment: “strongly agree” |

1.000 |

3.8 Quality of life measurement

QOL was assessed for change in the 42 patients which had all four questionnaires completed. The QOL measurement showed no significant change throughout the four time points measured during the treatment process (P = 0.246). The median QOL scores recorded in the “pre,” “mid,” “end” and “post” questionnaires were 8/10 (range 1-10), 8/10 (range 4-10), 8/10 (range 4-10) and 9/10 (range 2-10).

3.9 Post-treatment questions

Of 49 respondents, 44 (90%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statement “My pet has not had excessive side effects from radiotherapy.” One client each disagreed and strongly disagreed with the statement. The remaining 3/49 respondents were “neutral.”

Of 49 respondents, 47 (96%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statement “I am happy I chose to treat my pet with radiotherapy.” Of 49 respondents, 2 were neutral and none “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with the statement.

Most owners (46/49, 94%) reported both that overall the radiotherapy experience was better than they expected, with 27 and 19 owners responding they “strongly agreed” and “agreed” with the statement “The radiotherapy experience was better than I expected,” respectively. Two respondents “disagreed” with the statement and one was “neutral.”

4 DISCUSSION

To the authors' knowledge this is the first study specifically evaluating the evolution of owners' attitudes towards radiotherapy in pets before and after gaining first-hand experience of the treatment modality. The results clearly show that client anxiety regarding the side effects of radiotherapy and repeat anaesthetics decrease after experiencing the process. This indicates that much of the anxiety surrounding radiotherapy in pets may be based on incorrect preconceptions regarding the expected side effects from radiotherapy and repeat anaesthetic procedures. Importantly, most owners (46/49, 94%) reported that the overall radiotherapy experience was better than they expected, 44/49 (90%) reported that their pet did not experience excessive side effects, and no owners reported being unhappy with their choice to treat their pet with radiotherapy.

QOL is of paramount concern for owners when making treatment decisions for pets. This is particularly true in oncologic cases where often the intent of treatment is not to cure the pet, but to extend good QOL. Minimizing side effects of treatment is therefore a primary goal.

Surrogate assessment of QOL in pets has been assessed in numerous studies,5-9 and it is generally agreed that an animal's owner is an appropriate surrogate. The current study utilized a simple numerical scale to estimate patient QOL, which may not reflect the true QOL of the patient. A more comprehensive questionnaire, such as the Canine Owner-Reported QOL questionnaire,18 may have allowed more accurate measurement of patient QOL. The primary aim of the current study, however, was to assess owner perceptions, rather than actual QOL, and therefore the more simple scale was chosen. The current study showed that undergoing radiotherapy did not significantly reduce QOL in patients, as judged by the pet's owner.

The current study is the first prospective study assessing client attitudes of radiotherapy in pets. It is also the first using multiple time points. The prospective study design and completion of questionnaires at the time of treatment will have reduced response bias which is likely to have been present in previous retrospective studies. Also, previous studies assessing owner perceptions of radiotherapy in pets had significantly higher proportions of animals receiving palliative radiotherapy.4, 14, 16 As palliative radiotherapy is used to directly reduce the morbidity associated with cancer, we expect the owners of these patients to have reported relatively fewer adverse effects. This is because the benefits of the treatment (eg, the reduction of pain associated with an osteosarcoma) will usually greatly outweigh the side effects of the treatment; hence, owners perceive a net improvement in their pet's QOL, even if they develop side effects.

In the current study, 43/49 (88%) of patients developed side effects according to the VRTOG toxicity criteria. Interestingly, only 2/49 (4%) of respondents perceived the side effects to be “excessive.” In previous studies, owners have reported their pets suffered adverse effects in 33% to 65% of cases, however, also reported an improvement in quality of life in 60% to 78%.4, 16 This indicates that while side effects may be common, they are often perceived to be tolerable and not negatively impact the patients overall QOL.

A limitation of the study was the inclusion of four patients receiving chemotherapy concurrently during their radiotherapy protocols, as concurrent treatment may have impacted perceived side effects. However, none of the owners of these animals felt their pet suffered excessive side effects of treatment, that is, none “disagreed” with the statement “My pet has NOT had excessive side effects from the radiotherapy treatment,” indicating that this would not have impacted the results. Only one of the owners of a pet receiving chemotherapy concurrently with radiotherapy (vinblastine for MCT) reported concerns about the side effects of radiotherapy following treatment (“disagreed” with the statement “I do NOT have any concerns about the side effects of treatment”). This patient had grade 2 skin side effects.

Only 2/49 (4%), patients suffered grade 3 side effects. The first was a dog with an oral sarcoma which had its protocol reduced (from a planned total of 48Gy to a total of 46.9Gy) because of the development of grade 3 mucous membrane and grade 2 skin side effects which were deemed unacceptable. Interestingly, this owner did not report that the side effects had been excessive, and in spite of these side effects at the end of treatment they responded that they felt it was the best treatment for their pet and were not apprehensive about the procedure, anaesthetics or potential radiotherapy side effects. The other patient was being treated for perianal fibrosarcoma with electron therapy and suffered grade three skin side effects. This owner reported having concerns about the side effects of radiotherapy and repeat anaesthetics following treatment, and was one of the two clients who did not “agree” or “strongly agree” that they were happy they chose to pursue radiotherapy.

Only two owners reported that their pet suffered excessive side effects. Of these two cases, the first was a pituitary macroadenoma which suffered no adverse effects according to the VRTOG toxicity criteria, making the questionnaire response difficult to explain. It is possible that the negative responses were due to severe neurologic impairment because of the tumour or side effects from concurrent steroid use. The second patient had a perianal fibrosarcoma and, prior to radiotherapy, had postoperative complications including a draining-sinus. During radiotherapy, this patient suffered grade 3 skin side effects and the owner also felt their pet did not tolerate repeated anaesthetics well.

The majority of patients did not have problems with repeat anaesthetics, with only 3/49 perceiving that their pet had problems with repeat anaesthetics. Specific anaesthesia protocols were not included in the study and future investigations would require determining if variables related to the anaesthesia (eg, the choice of anaesthetic drugs) influences a pet's perceived QOL during treatment.

Importantly, the vast majority of owners (46/49, 94%) reported that the radiotherapy experience was better than they expected. These results indicate that for most owners the procedure exceeds their expectations. Of the two respondents who reported the process was worse than expected (one other respondent was “neutral”), one was the previously mentioned dog with an oral sarcoma which suffered grade 3 side effects related to the oral location of the tumour. The other was a cat with central nervous system lymphoma which suffered significant disease-related neurological symptoms throughout treatment. Interestingly, in both the cases, the owners still “strongly agreed” with the statements “I support the treatment of radiotherapy in pets” and “I feel radiotherapy was the best treatment for my pet.” This indicates that even when the experience was not as positive as expected, it was still considered worthwhile by the owners.

In the current study, the most common definitive radiotherapy protocol involved 12 fractions of 4 Gy (a total of 48 Gy) given on a Monday, Wednesday, Friday basis. Other centres may use more hyperfractionated protocols (eg, daily fractions) which may have more severe acute adverse events or anaesthetic complications which would impact on client attitudes.

The current study is in agreement with previous studies4, 14 in that the majority of clients reported that, if given the choice, they would go through radiotherapy again. This repeatable finding indicates that overall veterinary radiotherapy is considered beneficial and worthwhile to clients who have gone through the experience with pets with cancer. Crucially, all respondents in the current study supported the use of radiotherapy and none felt that radiotherapy was not the best treatment choice for their pet.

This study has several limitations. First, the study naturally selected for clients willing to proceed with radiotherapy, a group that may have been more likely to report a positive view of the procedure. Also, not all questionnaires were completed by the same owner of patients, which may have introduced some variability in responses. Finally, only acute adverse events were included in the study (because of the period of sampling), so the impact of late effects on client attitudes was not assessed.

Another limitation was the exclusion of patients that did not complete the full radiotherapy course, as they could not be included if they did not complete a “post-treatment.” Of the 17 patients which did not complete their originally prescribed radiotherapy course during the study period, only 6/17 were due to acute radiotherapy adverse events. Of these six patients, two completed the questionnaires and were able to be included in the study, mitigating this limitation to some extent. Of the 11/17 patients which did not complete the radiotherapy protocol for nonradiotherapy adverse event-related reasons, one patient was still able to be included in the study as they had previously completed a full course of radiotherapy, including questionnaires, successfully.

Our study measured owner opinions, while treatment was ongoing. Previous studies have used retrospective surveys which have numerous inherent limitations, particularly when measuring subjective responses. The current study showed a clear improvement in owner attitude towards radiotherapy in pets as their pet went through the procedure.

5 CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that radiotherapy is well tolerated by pets as judged by owners and the anxiety associated with undergoing radiotherapy and repeat anaesthetics is significantly alleviated after going through the process. These results will help veterinarians allay client concerns when discussing radiotherapy with clients, and will hopefully lead to an increase in clients pursuing radiotherapy for appropriate diseases in pets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the University of Glasgow.

APPENDIX 1: PRE-TREATMENT QUESTIONNAIRE RADIOTHERAPY QUESTIONNAIRE—PRE-TREATMENT

APPENDIX 2: MID-TREATMENT QUESTIONNAIRE RADIOTHERAPY QUESTIONNAIRE—MID POINT

APPENDIX 3: END-TREATMENT QUESTIONNAIRE RADIOTHERAPY QUESTIONNAIRE—END OF TREATMENT

APPENDIX 4: POST-TREATMENT QUESTIONNAIRE RADIOTHERAPY QUESTIONNAIRE—CHECK UP