A Comparison of Optimal Tariffs and Welfare under No Lobbying, Domestic Lobbying and Domestic-foreign Lobbying

We would like to acknowledge financial support from the key project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 71333007). Xianhai Huang is grateful for the financial support from National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 11AZD009), Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (No. 2009JJD790044), and the project of Centre for research in regional economic opening and development of Zhejiang province (11JDQY01YB). Jie Li (the corresponding author) would like to thank the support by the project of Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY13G020002). The authors would also like to thank the editor, two anonymous referees and the participants of the Fifth IEFS China Conference 2013 for their valuable comments and suggestions. All the remaining errors are, of course, ours.

Abstract

Whether and what type of the lobbying-induced trade policies can improve the domestic welfare? We show that as compared to the case of no lobbying and the case of domestic lobbying, the domestic-foreign lobbying may achieve the lowest tariff and may also realise the highest welfare for the domestic country. Our finding provides a theoretical explanation to the prevalent lobbying competition between Asian firms and US firms in USA recently. We argue that the domestic-foreign lobbying may contribute to a freer trade in the domestic country, and lobbying competition may be one of the strongest forces pushing for trade liberalisation.

1 Introduction

In recent years, lobbying as a common phenomenon has played an important role in influencing trade policymaking. For instance, in 2009, more than 580 principals from some 137 countries participated in lobbying US policymakers, with the total spending in lobbying exceeding 484 million dollars, and most of them are from Asia. In 2009, Toyota spent about 5.2 million dollars in lobbying the US government, which is seven times more than its 1999 lobbying expenditure. Tata Consultancy Services and USINPAC from India and Lenovo, Huawei and Haier from China also lobby the US government for their benefits. On the other hand, the domestic firms in the US also lobby the US government actively. Google's lobbying expenditure in 2009 was $4.03 million, up by 44% as compared to 2008. Microsoft, HP, Tyco Electronics and MOTOROLA are also active lobbyists.

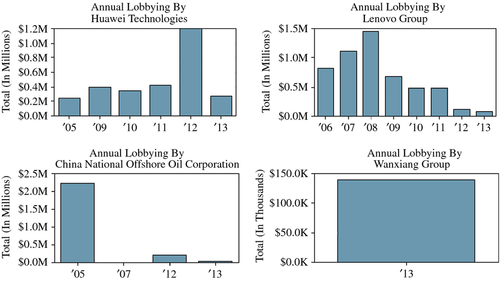

Among the foreign lobbyists, Chinese firms are very active in the eyes of the US government. According to the US political contribution database (opensecrets.org), the lobbying expenditure of Huawei and ZTE Corporation in 2012 reached $1.04 million and $90,000, respectively. In 2011, the lobbying spends of them are $425,000 and $182,000, respectively. There are also other Chinese firms such as Lenovo, China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and Wanxiang Group that began to participate in lobbying foreign countries more frequently in recent years (Figure 1). For example, in 2004, by lobbying the US government, Lenovo successfully initiated an acquisition of IBM global PC business valued at $1.25 billion. In 2013, CNOOC enhanced its lobbying to US congress to prepare for the acquisition of Nexen valued at $15.1 billion. Wanxiang Group spends $140,000 in lobbying in 2013 and is ready to take over American battery manufacturer A123 Systems.

The prevalent lobbying activities have aroused the great interests of many scholars, and numerous related literature has emerged concerning the effect of lobbying on trade policy. Although the literature dealing with the lobbying behaviour from the domestic firms has been abundant ever since Grossman and Helpman (1994),1 papers concerning foreign lobbying in determining trade policymaking have been relatively few, and most of them are empirical studies. For example, Mitchell (1995) found that from 1987 to 1988, the political contribution from foreign lobbying accounted for 5.6 per cent of the total corporate political contribution, and he stated that the lobbying of foreign firms is as intensive as that of domestic firms. Gawande et al. (2006) found that foreign lobbying on average decreases the most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariff applied by the United States, and they also showed that foreign firms’ lobbying to reduce the MFN tariff is still effective while the domestic firms lobby the government to increase the tariff. Kee et al. (2007) found that foreign lobbying power would significantly influence the preferential market access granted by the US. In fact, Silva (2011) found that the lobbying of Latin American exporters and US importers plays an important role in determining the preferential market access granted by the US.

In international trade, the major goal of foreign lobbying is to push for freer trade policy, such as cutting the tariff, whereas domestic firms aim to derive the government's trade protection. If the trade policy is affected by both foreign and domestic lobbying, we then wonder whether and what type of the lobbying-induced trade policy can improve domestic welfare. To this end, we construct a simple duopoly model and conduct a comparison of the optimal tariff choices and welfare consequences under three different scenarios: no lobbying, domestic lobbying, that is, only domestic firms participate in lobbying the domestic government, and domestic-foreign lobbying, that is, both domestic and foreign firms are active and compete with each other in lobbying the domestic government.

We find the following results: as compared to the case of no lobbying and the case of domestic lobbying, the domestic-foreign lobbying achieves the lowest tariff, if the relative effectiveness of foreign lobbying is sufficiently high. Moreover, if the relative effectiveness of foreign lobbying is high enough, the welfare under domestic-foreign lobbying achieves the highest social welfare, but if the effectiveness is relatively low, the welfare under domestic-foreign lobbying would be lower than that under the social optimum or even that under domestic lobbying, when the government is sufficiently avaricious and the product differentiation between the goods of the two firms is sufficiently small.

Our results imply that the domestic-foreign lobbying may contribute to a freer trade in the domestic country, and lobbying competition may be one of the strongest forces pushing for trade liberalisation when the relative lobbying effectiveness of foreign firms is high enough.

Our findings lend some support to the evidence in the real world. For example, in 2005, the Chinese firm, CNOOC, failed in merging with the ninth largest oil corporation in US, Unacol, as its competitor in US, Chevron Group, convinced the US government and investors that the safest option for Unacol was to be merged by a domestic company. In addition, in 2012, Huawei failed to access the US market because of the lobbying of its competitors in US such as Cisco Systems, and Huawei was refused for the reason of threatening US national security. Such barriers or oppositions to foreign lobbying, to a large extent, are associated with the worries about the adverse welfare effects on US. However, our results suggest that the prevalent lobbying competition between Asian firms and US firms in the USA may improve the welfare for USA.

Our model has the structure of a common agency problem: to induce a government (a common agent) to act on their behalf, firms (principals) offer the government payment schedules, which link non-negative transfers to each action the government might take. Foreign firms lobby for free trade of exports, whereas import-competing domestic firms lobby for protection from imports. Our approach draws on Bernheim and Whinston (1986) and Dixit et al. (1997), who characterise the equilibrium for a class of common agency problems. The approach has been largely applied to examine lobbying behaviours of domestic firms towards the formation of trade policy. For example, Grossman and Helpman (1994) consider the determination of tariffs across sectors, Chang (2005) examines trade policy under monopolistic competition, and Kayalica and Lahiri (2007) explore national policies towards foreign domestic investment. Bombardini (2008) and Bombardini and Trebbi (2012) also analyse firm-level contribution decisions. An exception is Konishi et al. (1999), who analyse the government's choice between a voluntary export constraint and a tariff in the presence of lobbying by both domestic and foreign firms; but they focus on the policymaker's choice between voluntary export constraints and tariffs, but their results are derived under the setting of Cournot competition and they pay little attention to other types of competition such as Bertrand, and production differentiation between firms is absent in their model.

This study extends the previous studies of trade protection by considering different oligopolistic competition modes, that is, Cournot duopoly and differentiated Bertrand duopoly. Specifically, we explore the optimal trade policy chosen by the domestic government under domestic-foreign lobbying and compare its welfare consequence with that of domestic lobbying and the social optimum (no lobbying). The model set-ups that are most related to ours are Kikuchi (1998) and Kagitani (2009). Kikuchi (1998) explored how optimal trade policy is affected by the competition modes without considering the lobbying behaviour from firms, while Kagitani (2009) extended the Kikuchi model to investigate the scenario of domestic lobbying. In contrast to these two papers, our model further incorporates the lobbying competition between domestic and foreign firms and its impact on the domestic trade policymaking and domestic social welfare under both oligopolistic quantity and price competition, which are absent in the above two papers.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the setting of the model. Section 3 derives the politically determined tariff and welfare effect of domestic-foreign lobbying under Cournot competition and makes comparisons with the no-lobbying case and the domestic lobbying case. Section 3.1 verifies the results under differentiated Bertrand competition. Section 3.2 states the concluding remarks.

2 Basic Model

Consider a duopoly model in a domestic market. There are two countries, domestic and foreign. Each country has only one firm producing a homogeneous good. The domestic firm produces good X, while the foreign firm produces good Y. The foreign firm exports its product to the domestic market and competes with the domestic firm there. We assume that the marginal cost of the domestic firm and that of the foreign firm are 1 and c, respectively. A quantity tariff t is imposed on the exports from the foreign firm by the domestic government.

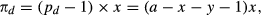

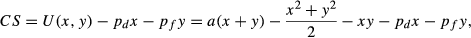

(1)

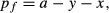

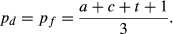

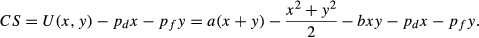

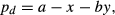

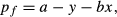

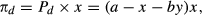

(1) , x and y are the consumption amount of good X and good Y, respectively, and pd and pf denote the prices of good X and good Y in the domestic market, respectively.

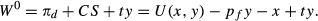

, x and y are the consumption amount of good X and good Y, respectively, and pd and pf denote the prices of good X and good Y in the domestic market, respectively. (2)

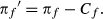

(2) (3)

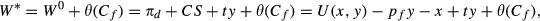

(3) (6)

(6) (7)

(7) (8)

(8) (9)

(9) (10)

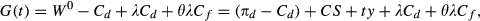

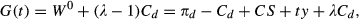

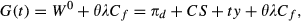

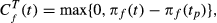

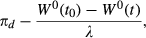

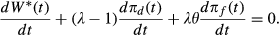

(10)Given the firms’ contribution schedules, the government chooses tariff t to maximise its objective function. It should be noted that there are four cases: (i) both firms do not lobby the government; (ii) only the domestic firm lobbies the government; (iii) only the foreign firm lobbies the government;4 and (iv) both firms lobby the government.

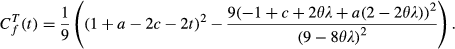

Clearly, in case (i), the domestic government's objective function will be reduced to 6, and we denote the optimal tariff chosen by the government in this case by t0 and call it the no-lobbying case.

(11)

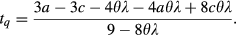

(11) (12)

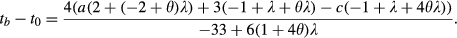

(12)In case (iv), the objective function of the government is exactly 9, and we denote the optimal tariff by tb and call it domestic-foreign lobbying case.

(13)

(13) (14)

(14)We then consider a simple three-stage game. In stage one, the two firms simultaneously provide the government with their campaign contribution schedules. In stage two, the government sets the tariff imposed on the foreign firm. In stage three, both firms compete in the domestic market à la Cournot (Bertrand), and they choose their outputs (prices) according to the tariff level. Backward induction method is adopted to solve this game.

3 Tariff and Welfare Comparisons under Cournot Duopoly

We consider the Cournot competition in this section, that is, in the third stage, the two firms engage in output competition.

(15)

(15) (16)

(16) (17)

(17) (18)

(18) (19)

(19) (21)

(21)In the second stage, the domestic government sets the tariff imposed on the foreign firm. There are four cases:

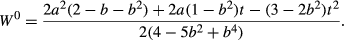

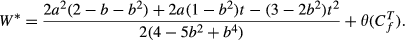

(22)

(22) (23)

(23) (24)

(24) (25)

(25) (26)

(26) (27)

(27) (28)

(28) (29)

(29) (30)

(30) (31)

(31) (32)

(32) (33)

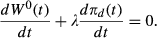

(33)Now, we move on to compare t0, tp, and tb. We will consider the following two cases.

3.1 Case 1: The Foreign Firm is More Efficient than the Domestic Firm, that is c < 1

(34)

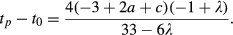

(34)Obviously, as long as λ ≠ 1, 34 is larger than zero, which immediately implies that t0 < tp. This result demonstrates that when goods X and Y are homogeneous, the tariff under the scenario of domestic lobbying is always higher than the social optimum.

(35)

(35) (36)

(36)We assume that a = 100 in our comparisons hereinafter. In Table 1, we give the ranges of λ in which tp > tb and tb < t0. The first row denotes the effectiveness of foreign lobbying. We find that θ must be lower than 0.7 to ensure that both firms lobby the government. The second row gives conditions for the occurrence of lobbying5 (range of λ) corresponding to different values of θ. Rows 3 and 4 show the ranges of λ such that tb < tp and tb < t0, respectively. Taking row 3 and column 3 for example, (1, 1.5) denotes when θ = 0.1 and 1 < λ < 1.5, lobbying occurs and tp is greater than tb; otherwise, when θ = 0.1 and 1.5 < λ < 2, lobbying occurs but tp is greater than tb. We can summarise the pattern implied by Table 1 as the following two results:

| Foreign lobbying effectiveness | θ = 0.1 | θ = 0.2 | θ = 0.3 | θ = 0.4 | θ = 0.5 | θ = 0.6 | θ = 0.7 | |

| Conditions for Lobbying to occur | λ < 2 | λ < 2.1 | λ < 2.5 | λ < 1.9 | λ < 1.5 | λ < 1.25 | λ < 1.06 | |

| Results | tb < tp | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5)a | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a |

| tb < t0 | (1, 1.05) | (1, 1.1) | (1, 1.2) | (1, 1.25) | (1, 1.3) | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a | |

Note:

- a indicates that tp > tb or tb > t0 holds for the full range of λ in which lobbying occurs.

Result 1: When lobbying occurs tp > tb always holds if the foreign lobbying effectiveness is relatively high, that is, θ ≥ 0.5; otherwise tp < tb if θ < 0.5 and λ is relatively large.

Result 2: When lobbying occurs, tb < t0 always holds if the foreign lobbying effectiveness is relatively high, that is, θ ≥ 0.6; otherwise, tb > t0 if θ < 0.6 and λ is relatively large.

Results 1 and 2 imply that when goods X and Y are homogeneous and the foreign lobbying effectiveness is sufficiently high, the tariff under domestic-foreign lobbying is smaller than both the social optimum and that under domestic lobbying. The intuition behind it will be demonstrated after discussing case 2.

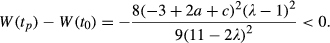

(37)

(37)Obviously, as long as λ > 1, 37 is less than zero, which immediately implies that W(tp) < W(t0). This result demonstrates that when goods X and Y are homogeneous, the welfare under the scenario of domestic lobbying is always lower than the social optimum.

Now, we make another two comparisons: W(tp) and W*(tb), and W*(tb) and W(t0). The results are given in Table 2, which are similar to Table 1.

| Foreign lobbying effectiveness | θ = 0.1 | θ = 0.2 | θ = 0.3 | θ = 0.4 | θ = 0.5 | θ = 0.6 | θ = 0.7 | |

| Conditions for Lobbying to occur | λ < 2 | λ < 2.1 | λ < 2.5 | λ < 1.9 | λ < 1.5 | λ < 1.25 | λ < 1.06 | |

| Results | w*(tb) > W(tp) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5)a | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a |

| w*(tb) > W(t0) | (1, 1.1) | (1, 1.2) | (1, 1.4) | (1, 1.45) | (1, 1.4) | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a | |

Note:

- a indicates that w*(tb) > W(tp) or w*(tb) > W(t0) holds for the full range of λ.

Result 3: When lobbying occurs, W*(tb) > W(tp) always holds if the foreign lobbying effectiveness is relatively high, that is, θ ≥ 0.5; otherwise, W*(tb) < W(tp), if θ < 0.5 and λ is relatively large.

Result 4: When lobbying occurs, W*(tb) > W(t0) always holds if the foreign lobbying effectiveness is relatively high, that is, θ ≥ 0.6; otherwise, W*(tb) < W(t0), if θ < 0.6 and λ is relatively large.

3.2 Case 2: The Domestic Firm is More Efficient than the Foreign Firm, that is c > 1

We first consider the case of 1 < c < 2, which means that the domestic firm is a little more efficient than the foreign firm. Next, we make two comparisons: t0 and tp, and W(t0) and W(tp). The results are the same as case 1, that is tp > t0 and W(tp) < W(t0). We then move to compare between tp and tb, and W(tb) and W(t0). The results are given in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The tables show that the results of case 2 are similar to case 1.

| Foreign lobbying effectiveness | θ = 0.1 | θ = 0.2 | θ = 0.3 | θ = 0.4 | θ = 0.5 | θ = 0.6 | θ = 0.7 | |

| Conditions for Lobbying to occur | λ < 2 | λ < 2.1 | λ < 2.5 | λ < 1.9 | λ < 1.48 | λ < 1.25 | λ < 1.06 | |

| Results | tp > tb | (1, 1.5) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48)a | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a |

| tb > t0 | (1, 1.05) | (1, 1.11) | (1, 1.17) | (1, 1.25) | (1, 1.3) | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a | |

Note:

- a indicates that tp > tb or tb > t0 holds for the full range of λ in which lobbying occurs.

| Foreign lobbying effectiveness | θ = 0.1 | θ = 0.2 | θ = 0.3 | θ = 0.4 | θ = 0.5 | θ = 0.6 | θ = 0.7 | |

| Conditions for Lobbying to occur | λ < 2 | λ < 2.1 | λ < 2.5 | λ < 1.9 | λ < 1.48 | λ < 1.25 | λ < 1.06 | |

| Results | w*(tb) > W(tp) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48) | (1, 1.48)a | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a |

| w*(tb) > W(t0) | (1, 1.1) | (1, 1.2) | (1, 1.28) | (1, 1.33) | (1, 1.4) | (1, 1.25)a | (1, 1.06)a | |

Note:

- a indicates that w*(tb) > W(tp) or w*(tb) > W(t0) holds for the full range of λ in which lobbying occurs.

In sum, when 0.6 ≤ θ ≤ 0.7, we have tb < t0 < tp and W*(tb) > W(t0) > W(tp). Hence, in this case, lobbying competition between the domestic and the foreign firms not only contributes to freer trade but also improves the welfare of the domestic country under Cournot competition. On the other hand, when 0 ≤ θ < 0.6 and λ is relatively high, tb is larger than t0, and W*(tb) is smaller than W(tp). When 0 ≤ θ < 0.5 and λ is relatively high, tp is smaller than tb, and W*(tb) is smaller than W(t0).

Now, we wonder whether the results still hold when the domestic firm is much more efficient than the foreign firm, namely, c > 2.

In the case of c > 2, we find that tb < tp, tb < t0, W*(tb) > W(tp) and W*(tb) > W(t0) do not always hold even if θ is sufficiently large. Take θ = 0.6 for example: when both λ and c are relatively high, that is, c > 17, we get the opposite results, namely, tp < tb, tb > t0, W*(tb) < W(tp) and W*(tb) < W(t0). In particular, when c is sufficiently large, that is, c > 25, lobbying will not take place at all. On the other hand, when θ is sufficiently close to zero, lobbying will not take place, either.

The intuition of all the above results is simple: the domestic-foreign lobbying constitutes a common agency problem in which firms induce the policymakers to act in their interests by means of contributions. The policymakers, however, being the common agent, can take advantage of the ‘prisoner's dilemma’ nature of the game and choose to maximise firm contributions by increasing the profit of the firm that is ‘perceived’ to be more competitive by bending trade policy in its favour, regardless of its nationality. This is because under truthful Nash equilibrium, changes in each firm's contributions would be exactly the same as the changes in its profits from its base level of pay-off, that is, the pay-offs that one firm lobbies while the other firm does not lobby, and the government (the agent) can extract all the surplus from the two firms. Thus, in an effort to maximise firm contributions, policymakers choose to increase the profitability of the firm that is perceived to be more profitable by bending trade policy in its favour. As the de facto weights that the government attaches to domestic contribution and foreign contribution are, respectively, (λ – 1) and θλ, the competitiveness of the domestic firm and foreign firm in the eyes of the government can be captured by (p – c)(λ – 1) and θλ(p – 1), respectively, that is, their respective adjusted markups in the eyes of the government. By comparing (p – c)(λ – 1) and θλ(p – 1), the government can identify the more competitive firm and makes biased policies in its favour. Therefore, when the foreign firm's lobbying is sufficiently effective, the government will attach more weight to the foreign firm. However, when foreign firm's lobbying is not effective enough while the government is too avaricious, that is, λ is relatively large, it is possible that (p – c)(λ – 1) > θλ(p – 1), resulting in tb larger than both t0 and tp. This implies that if the contribution from the foreign firm dissipates too much on the way, the possibility for a freer trade environment via lobbying is small.

The domestic-foreign lobbying may achieve the highest welfare because the foreign contributions constitute a net transfer of income to the domestic country. If foreign contribution dominates the welfare loss generated by lobbying, welfare may improve. This is likely to take place if the foreign contribution does not dissipate too much on the way, that is, θ is sufficiently large.

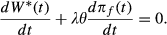

Does this result hold when the firms engage in price competition? In the following section, we will examine this question.

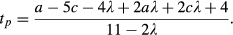

4 Tariff and Welfare Comparisons under Differentiated Bertrand Duopoly

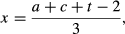

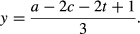

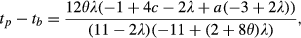

In this section, we discuss the differentiated Bertrand competition, that is, in the third stage, the two firms engage in price competition.

(38)

(38)We assume that 0 < b < 1, where b is the measure of product differentiation between the two firms. 0 < b < 1 implies that the two products are substitutes and the inverse demand for each differentiated good is more sensitive to its own supply than that of the opponent.

(39)

(39) (40)

(40) (41)

(41) (42)

(42)The rest of the model setting is the same as in Section 2.

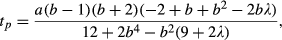

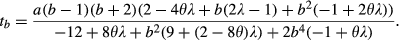

(43)

(43) (44)

(44) (45)

(45) (46)

(46) (47)

(47) (48)

(48) (49)

(49) (50)

(50) (51)

(51) (52)

(52) (53)

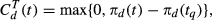

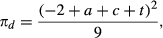

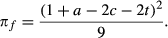

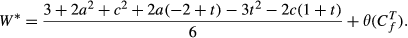

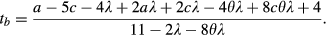

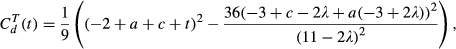

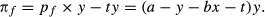

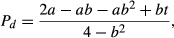

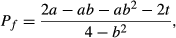

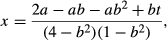

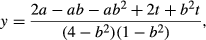

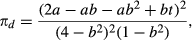

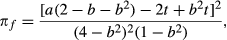

(53)Now we can calculate πd(tp) and πf(tq). By substituting them into 13 and 14, respectively, we get  and

and  , which can be further used to calculate W*(t).

, which can be further used to calculate W*(t).

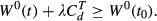

Result 5: When lobbying occurs, we have that tb < t0 < tp and W*(tb) > W(t0) > W(tp) if the foreign lobbying effectiveness is relatively high, that is 0.82 ≤ θ ≤ 0.97; otherwise, when 0 < θ < 0.82, we have that tb > t0, W*(tb) < W(tp), t0 < tp < tb, and W*(tb) < W(t0) if both λ and b are sufficiently large.

From Result 5, we conclude that the results in Section 3 largely remain to hold under price competition. Moreover, we can also show that if the relative effectiveness of foreign lobbying is sufficiently high, lobbying competition between the domestic and the foreign firms not only contributes to freer trade but also improves the welfare of the domestic country. However, in the case where the effectiveness of foreign lobbying is relatively low, the welfare under the domestic-foreign lobbying would be lower than that under social optimum or even that under domestic lobbying, should the government be sufficiently avaricious and the product differentiation between the goods of the two firms is sufficiently small.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we find that lobbying competition between the domestic and foreign firms may contribute to a freer trade in the domestic country. Moreover, as compared to the case of no lobbying and the case of domestic lobbying, the domestic-foreign lobbying may probably realise the highest welfare for the domestic country. In other words, lobbying competition may be one of the strongest forces pushing for trade liberalisation. This happens primarily because it is easier for foreign lobbies to compensate the government for the distortions associated with changes in trade policy, as contributions from the foreign lobbies may receive a heavier weight than domestic contributions.

Our findings may have some implications for the current trade policies adopted by US government. Many Asian foreign firms are denied access to the US market because US domestic firms dominate the Asian foreign firms in the lobbying competition, which can be largely accrued to the low effectiveness of foreign lobbying, for example, lack of experience and ability, and the US government's worries over welfare worsening effect generated by such lobbying competition.

We conclude by noting some limitations of our results. First, we have restricted our attention to tariffs to gauge the impact of lobbying on the political process. In the real world, the government holds a wide selection of policy tools. It is possible to examine how the optimal tariffs and the corresponding social welfare may be affected by each of these policies in the presence of lobbying. Second, it would also be interesting to consider the case in which the weights that the government attaches to firm contributions are endogenously determined.