The future of voluntary blood donation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Replacement blood donations are a major source of blood in KSA. This presentation highlights “the peace time and war experiences,” where the voluntary donor potential was tested.

The “Peacetime Experience”—King Saud University Student Donor Drive

This donor drive commenced in 1983 with 13 donors in its first and the annual collection reached 4500 blood units in the academic session 1995-1996, when the student enrollment was around 30,000. In 2018 the enrollment jumped to 120,000 students. If we add the staff and auxiliary personnel, the population of potential voluntary blood donors will be enough to cover the current and future blood needs of King Khalid University Hospital. Unfortunately, this drive did not survive due to administrative and organizational difficulties.

The “First” Gulf War Experience

At the end of 1990, when the Allied Forces started to end the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, the Saudi Ministry of Health waged a publicity campaign asking healthy individuals to donate their blood. The response was phenomenal, and the blood inventory in blood banks swelled about five- to sevenfold. First-time donors broke the “fear barrier,” went through the donation experience, and it is hoped they will return to donate voluntarily.

Conclusions

The major lesson learned from the King Saud University student donor drive and Gulf War experience is the enormous voluntary donor potential in Saudi Arabia. There is a need for forward planning to shift the current partial involuntary donor system to a voluntary system based on nonremunerated donors.

ABBREVIATIONS

-

- HBB

-

- hospital blood bank

-

- KKUH

-

- King Khalid University Hospital

-

- KSA

-

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

-

- M of H

-

- Ministry of Health

-

- WB

-

- whole blood

The 28th World Health Assembly, in 1975, passed a resolution (WHA28.72-23)1 and its subsequent revisit,2 calling for member states to engage actively in establishing national blood transfusion services based on voluntary nonremunerated blood donations. Such donation system is intended to safeguard the adequacy, sustainability, and safety of blood supplies. Developed countries have succeeded in establishing such donor system, administered by either National Transfusion Services, as in the United Kingdom or by the Red Cross as in United States and some European countries. This voluntary donor system not only allowed the recruitment and retention of blood donors but also ensured the adequacy of plasma that facilitated the production of wide-range plasma fractions, some manufactured by the National Transfusion organizations and others by commercial enterprises.

However, developing countries are still lagging behind in establishing a voluntary donation system. The hurdles they face have been reported extensively in the literature.3-6 Shortage of financial resources is the major hurdle in most developing countries, as it generates all other hurdles, such as lack of suitable premises, equipment, and consumables; shortage of trained staff; and poor general health and education of the population and prevailing misconception about giving away their blood. The situation is made worse by the fact that transfusion services have to compete for limited funds amid more urgent and pressing health priorities such as infectious and/or endemic diseases.

THE KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA –BACKGROUND

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) occupies the largest stretch of land (approximately 2,150,000 km2 [830,000 square miles]) of the Arabian Peninsula, stretching from the Red Sea in the west and the Arabian Gulf in the east. KSA is almost all arid desert with a mountainous area to the south. Its total population as of 2017 is 33 million—25 million Saudi nationals and 8 million foreigners. KSA is considered the central focus of Islam, as it is “the Land of the two Holiest shrines (Mosques),” in reference to Al-Haram (in Mecca) and Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi (in Medina).

KSA is the largest economy in the Middle East and the 18th largest in the world. It is the worldʼs second-largest oil producer behind the United States, is categorized as a World Bank high-income economy with a high Human Development Index, and is a member of the G-20 major economies.

The country has transformed rapidly through very ambitious development programs in all areas of life and services, including education and health care. The Saudis are now living a very comfortable life, where practically all services are offered free, particularly health care and education up to the university level.

THE BLOOD TRANSFUSION SERVICE IN KSA

The main health provider in this big stretch of desert country is the government through its Ministry of Health (M of H). To enhance the efficiency of health delivery, the M of H divided its service into five regional directorates: Central, Eastern, Western, Northern, and Southern regions. The M of H takes the biggest share of blood transfusion service in the country via the regional Directorate of Laboratories and Blood Banks. The Directorate is usually located in the largest of the regional main cities, with a regional blood bank in close proximity to the largest hospital. This blood bank, which is usually the largest in the region, is recognized as the “Central” blood bank for that region. It collects blood from donors, screens their blood, prepares the frequently consumed blood components (red blood cells [RBCs], fresh frozen plasma, platelet concentrate, and cryoprecipitate), and stores and issues these components to smaller city and other regional hospitals. The receiving hospitals usually provide donors in return. Blood donors are replacement donors, mainly relatives, coworkers, and friends of the patient in addition to a few but slowly growing number of voluntary donors.

However, the government-supported health service is also delivered by other independent organizations: university hospitals, military, National Guard, Security Forces, King Faisal Specialist Hospitals, and numerous private hospitals. Each of these hospitals has its own hospital blood bank (HBB) that undertakes all the functions of a transfusion service, from donor recruitment to blood components preparation, storage, and issue. Although these blood banks should following guidelines dictated by the M of H, the extent of conformation is rather erratic. All the regular forces HBBs (military, National Guard and Security Forces) are accredited by the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB). Others have started the lengthy accreditation procedure. Due to this excessive fragmentation of the transfusion services of KSA, it has proved almost impossible to plan or forecast when a united blood service will ever be achieved. Although a minimum degree of cooperation exists between HBBs in the same city, the establishment of the Saudi Transfusion Society is already fostering bonds between the transfusion specialists and administrators in different aspects of this fragmented blood transfusion system. In the face of this situation, there is a lack of accurate accumulated figures for the blood transfusion activities in the KSA, and it is therefore left to individual HBBs to keep its own records and analyze them and draw lessons that may help framing the future of transfusion service in that HBB. This approach has proved to be extremely valuable for us at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) blood bank and was the basis for numerous publications that offered a glimpse of various aspects of the transfusion practice in the KSA.7-12 The fragmented and predominantly hospital-based blood banking transfusion service in KSA is of course a big contrast to the more efficient, unified, and less costly transfusion service offered by the American Red Cross in the United States, or the national services in Canada and the United Kingdom.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE BLOOD DONOR SYSTEM IN THE KSA

In the past 5 decades (since the early 1970s), the KSA has witnessed phenomenal growth and expansion in health care. Modern hospitals were established in various provinces offering services in all areas of clinical medicine, including those too dependent on blood transfusion support, such as hematology/oncology, cardiac surgery, and accident and emergency. Accordingly, from the early beginnings (mid-1970s), a lot of pressure was put on the blood transfusion service to increase its blood supply to cover the increasing demand for blood products. Besides, as long as fit and healthy individuals are the only source of blood, all such people are potential blood donors. However, blood donation was new to this community unaccustomed to dispensing their blood. In the face of this situation, around 1975, blood banks were forced to use paid blood donors, all foreigners being paid 300 Saudi Riyals (US$70) per single whole blood (WB) donation, in addition to importing all blood products from abroad (mainly, Switzerland and the United States). Then there was the slow and gradual adoption of replacement donations, mainly family members and coworkers and friends: “no donation, no surgical operation.” Initially, there were few voluntary donors, mainly foreigners who were already blood donors in their home countries and fully acquainted with voluntary blood donation, with very scanty contribution from the local population. Some of the locals questioned why they were being asked to donate when the government had approved payment for donors. It was a hurdle to convince locals to donate their blood, even family donations, until eventually, in 1986, the government canceled donor payments.

Over the subsequent years, voluntary donations continued to grow due to the activity of outdoor blood collection teams who visited institutes of higher education, police and military colleges, government department headquarters, and other places of work and learning. In all these locations, blood donation was predominantly a male domain. At the KKUH blood bank, over the years, females constituted less than 5% of the blood donations,12 while they form almost 50% of the Saudi population. A similar disparity in the contribution of females exists in neighboring countries.13 In contrast, females in Western societies gave as high as 40% to 50% of donated blood.14, 15

Payment for donors was stopped and the importation of blood from abroad was phased out gradually by different hospitals; fortunately, this has coincided with the global AIDS scare that blood transfusion can transmit the disease, which was not known in KSA, at the time. There was then a general belief that imported blood was not safe and could transmit the disease. This helped with the rigid enforcement of the policy of “no blood donation, no surgery” or “admission to hospital,” which has greatly affected patients going for open heart surgery who had to provide at least 15 donors before admission for surgery. This policy served two purposes: First, it safeguarded the constant input of donations to allow the blood bank to fulfill its obligations toward emergencies requiring hemotherapy. It also allowed blood banks to build enough stock of blood products to fulfill their obligations to acute emergencies as well as supportive therapy for hematology/oncology patients and surgical operations, including open heart surgery and, more recently, transplant surgery including bone marrow transplant in some main hospitals. Second, it helped in laying the bases for potential future “voluntary” blood donations, particularly first-time donors, who, in this system of involuntary blood donation, are forced to overcome the “fear barrier.”16 Table 1 gives a timeline for the key developments in the blood donor services in the KSA (Table 1).

| Timeline | Sources of blood services |

|---|---|

| Mid-1970s | • Establishment of hospital blood banks |

| • Paid donors + imported blood products | |

| 1980 | Paid donors = imported blood + family donations |

| 1982 (KKUH opened in 1982) | Paid donors = imported blood + family donations |

| 1985 | Paid donors = imported blood + family donations + start of outdoor door (voluntary) campaigns |

| 1986 to present | Family donations and expanding outdoor (voluntary) campaigns cessation of imported blood products |

| 1990-1991 | The First Gulf War and flooding of voluntary donors; blood stocks expanded about 5-7 times (consumption was minimum and excessive expiry and loss) |

| Current donors | Mixture of replacement donors, approximately 40%-60%, and the rest are voluntary donors |

However, looking at the long-term future of the blood transfusion services in the KSA and the establishment of a voluntary donor system, we present the following evidence that we have drawn from both “peace” and “war” experiences.17 We uncovered the enormous voluntary donor potential that suggests the establishment of a blood transfusion service totally dependent on voluntary blood donations is possible and attainable in KSA.

KSU STUDENT DONOR DRIVE—THE “PEACETIME EXPERIENCE”

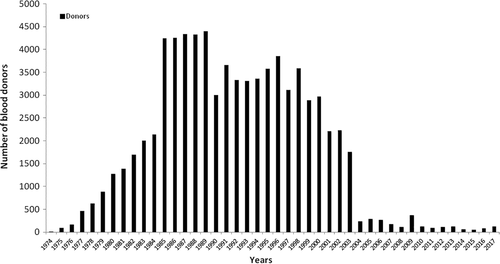

This activity started in 1974, with 13 donors in its first year, when the university colleges were spread out in different locations in old Riyadh City. When all colleges shifted, 7 years later, to the new modern campus north of Riyadh, blood donations became more organized and centralized in one big center. The donor drive was then organized by the KKUH Blood Bank and KSU Deanship of Student Affairs. The latter prepared a spacious and well-equipped donor facility, in the Student Health/Entertainment Center, in the middle of the campus, that was open throughout the academic year. The University Hospital and the M of H Central Blood Banks were the only blood collectors. Blood donors found it easy to reach the donor center; their number picked up over the years, and the annual donations reached its maximum, 4500 donors, 10 years later in the academic year 1986 to 1987 (Fig. 1). The donors were predominantly university students. The number of single blood bags collected each day (20-50 bags) was determined according to blood group type and the inventory shortage. As incentive to student blood donors, the Deanship of Student Affairs used to give low-price gifts (clocks, wristwatches, Saudi head dress “Ghutra,” stamped with the university emblem). A “University Blood Donation Trophy” was awarded annually to the college that donated the maximum number of units. Each year, the university rector was the first to donate, and his inauguration of the blood donor drive is given wide publicity within and outside the university.

The KSU donor drive was a model that was gradually being followed by other blood banks in the city as their donor campaigns reached educational, civil, and military institutes as well as government departments. It formed an excellent basis for the future national voluntary blood donation.

Two further remarks need to be added about the enormous potential of the KSU donor drive: First, most donors donate only once a year; that is, the total number could easily be doubled if the donors were asked to repeat their donations at least twice a year. Second, no target figure for the total number of donations was set. Indeed, the number of donors (shown in Fig. 1) could easily be increased to a predetermined calculated target number, if judicious use could be made of all the collected blood.

The experience of the KSU donor drive was taken to indicate the enormous voluntary blood donor potential in this small selected sector of the Saudi society. The number of enrolled students at KSU at the time was approaching 30,000 students, and in 2018 the number jumped to over 120,000 students—all potential student donors. If we add the number of staff, both academic and nonacademic, and their families, the total potential voluntary blood donor population at KSU could be well above 200,000, enough to cover the current (about 12,000 blood units) and future blood needs of KKUH.

Unfortunately, the KSU donor drive did not survive long for many administrative and organizational difficulties. Nonetheless, this donor drive remains strong evidence to the existence of a huge donor potential that has been tested and proven. If the administrative difficulties that terminated the KSU student donor drive prematurely could be sorted out by the University administration, this donor drive could readily provide KKUH with all its needs for blood products.

THE FIRST GULF WAR EXPERIENCE

Toward the end of 1990, when the Allied Forces decided to end the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, the Saudi Ministry of Health formed a national emergency committee of representatives of civil and military health establishments in Riyadh to draw a national plan to safeguard the supply of enough blood should war break. The committee waged a publicity campaign in TV, radio, and newspapers, in addition to displaying posters all around the city of Riyadh (population at that time <3 million), inviting healthy individuals to donate their blood at any nearby HBB. War again proved to be a very strong motivating stimulus for blood donation.18, 19 The response of the public was phenomenal, and all blood banks stocked blood to the maximum their storage facility could take.

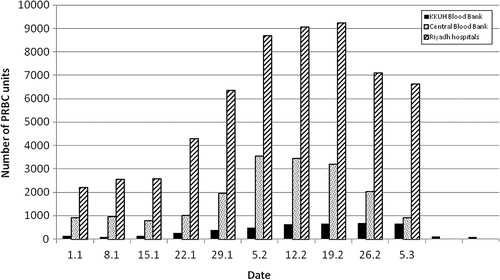

Just before the war, it was agreed that blood banks in the seven major hospitals in the city of Riyadh—KKUH, Shimaisi Hospital (Central Blood Bank), King Faisal Specialist Hospital, King Fahad National Guard Hospital, Riyadh Kharj Military Hospital, Prince Salman Hospital, and Security Forces Hospital—would join a fax-based common blood inventory of WB, RBCs, platelet concentrate, fresh frozen plasma, and cryoprecipitate. Figure 2 shows summaries of the RBC stocks in two blood banks, KKUH Blood Bank and the M of H Central Blood Bank, and the gross total space inventory in all major blood banks in Riyadh. The midweek (Tuesday) RBC inventory at our hospital was recorded 2 weeks before the Gulf War started (January 1, 1991) up to 5 weeks after the end of the war. Before the war, the RBC inventory at our University Hospital blood bank (Fig. 2) was kept at about 120 units. However, and in response to the donor recruitment campaign, the RBC inventory doubled in the first week of the war and continued to rise to approximately seven fold by the fourth week. When the war ended, there was the expected sudden drop in the donor input, and the blood bank was left with an enormous RBC inventory, which was allowed to expire. Two weeks after the end of the Gulf War, the WB inventory was back to the prewar level. A similar pattern in donor input was noted in the gross total inventory of RBCs in Riyadh, which increased four and a half times from about 2000 units before the war to a maximum around 9000 units, and then dropped gradually to the prewar inventory (Fig. 2).

The major lesson learned from the Gulf War experience as well as the KSU student donor drive is the enormous potential for expanding the voluntary blood donations in Saudi Arabia. The potential number of donors and donations is much larger that can be used by blood banks. The 2018 WB needs of KKUH can readily be covered by 12,000 donations, as mentioned earlier, a number that can be covered by the neighboring KSU student voluntary donor drive. Finally, the Gulf War donor campaign gave an opportunity to first-time donors to break the “fear barrier” and pass through the donation experience and get the self-satisfaction that ideally will bring them to donate voluntarily.

A LOOK AT THE FUTURE OF BLOOD DONATION IN SAUDI ARABIA

The current modernized structure of the health services in Saudi Arabia, including the blood transfusion service, have received unlimited governmental support. The support for the transfusion service is noted in the spacious premises and modern automated systems operated by computer-based management systems and highly qualified technical staff. However, these modernizations are established only in the busy transfusion services in the big cities and have not reached the peripheral blood centers. Finally, there is yet another government encouragement to blood donors. Those blood donors who donated 10 times are honored by a gold-plated medal and a decorated certificate awarded by the Royal Court.

So the critical question arises: What is the future for blood donation in Saudi Arabia? The answer to this question takes us deeper into blood donation as a newly introduced social behavior in a community unaccustomed to donating their blood. In this respect, social behaviors have frequently been explained by two theories: “the theory of reasoned action”20 and its extension, “the theory of planned behavior.”21

The theory of reasoned action advocates that behaviors are under voluntary control and are determined by the attitude toward the action to be undertaken. In blood donation, attitudes represent the individualʼs feelings and beliefs about giving blood; if the attitude of an individual is positive toward blood donation, he will donate blood; if it is negative, he will not. On the other hand, the theory of planned behavior proposes that people who do not exercise total control over their behavior or whose behavior is not totally their decision can be influenced by others to adopt the behavior. Accordingly, those with a negative attitude toward blood donation could be educated and motivated to change their negative knowledge and beliefs about blood donation, in the hope of changing their attitude, and start donating their blood. These two theories have repeatedly been tested and confirmed in blood donation and continue to be the bases for the titles of the uncountable published studies on knowledge, beliefs, and attitude toward blood donation.22

We have undertaken three similar studies among Saudis to test their knowledge, beliefs, and attitude toward blood donation; all were structured questionnaire-based surveys. The first study was among blood donors (n = 517) and their friends or relatives who attended in the company of those who donated but did not donate (n = 316).7

The overwhelming majority of both donors and nondonors showed a positive attitude toward blood donation and its importance for patient care, and objected to the importation of blood from abroad.

Blood donors believe that blood donation is a religious obligation and that no reward should be given but may accept a token gift, and they do not mind coming themselves to the donor center to give blood. A minority (34%) agree to donating up to six times a year. On the other hand, one-half of the nondonors were not asked to give blood, and a small minority (16%) stated fear and lack of time as their main deterrents. The majority of nondonors objected to money compensation, but 69% will accept token gifts as incentives to their blood donation, and 92% will donate if a relative or friend needs blood. The conclusion of this study uncovered an encouraging strong belief and very positive attitude toward blood donation by both donors and nondonors.

The second and third subsequent studies were separate surveys on male23 and female24 university students, respectively. This young group was selected because they are the future blood donors in Saudi Arabia. Also being educated will facilitate their participation and responses to the written questionnaire-based surveys.

The second study, among male university students,23 aimed to probe the attitude of KSU male students (n = 600), both donors and nondonors. The overwhelming majority, 98% of the respondents agreed that blood donation is important, and a similar percentage of nondonors recognized the continuous need of blood banks for blood donors and were opposed to importing blood from abroad, reflecting their view that blood should be made available locally. The majority of the students, both donors and nondonors, did not consider fear or location of the donation center strong discouraging factors against blood donation and objected to monetary compensation, but would accept a token gift. This survey highlighted the need to invest in awareness and motivational campaigns on blood donation among university students so that current donors will continue donating and nondonors will be encouraged to begin donating. Addressing the issues raised by the nondonors will pave the way to their becoming regular blood donors. This will eventually facilitate the establishment of a blood donor system based on voluntary, nonremunerated donations.

The third study was among female university students only.24 This sex group was chosen for a separate survey because it is the experience of major local blood banks that Saudi females constitute less than 5% of blood donors. As the demand for blood is ever increasing, there is a need to identify the factors that discourage females from donating their blood and subsequently find approaches to enhance their share as blood donors. This study, which is also a questionnaire-based, cross-sectional, descriptive study, recruited female students (n = 300) from six colleges: Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Science, Arts, and Business Administration at KSU. The majority of participants (75%) are unaware that females constitute less than 5% of donors but know that blood banks are in continuous need of donors to give support for needy patients, particularly road traffic accidents and surgical patients. Interestingly, misconception about blood donation, such as fear of infection, prevailed widely among female students.

A minority of participants (10%-30%) would donate as a religious obligation or need of a relative or friend (50%-60%) but not for money (90%-97%). The most prominent hurdle preventing females from donating their blood was difficulty reaching the blood bank, as they cannot drive cars or move alone in public transport (only recently, in 2018, females were permitted to drive cars). A similar observation from Saudi Arabia was reported before.25 Most respondents will donate if blood collection is done at their colleges and other places of gathering such as shopping malls. The study concluded that the attitude of Saudi female students toward blood donation is positive, and the few misconceptions that emerged could be corrected by health awareness campaigns. Careful organization of blood collection efforts that would observe the special status of women in the society by reaching them in their colleges and other places of gathering could enhance female donor input markedly.

CONCLUSIONS AND “THE WAY FORWARD”

“The further back you can look, the further forward you are likely to see.”

Sir Winston Churchill

As to “the way forward” from what we have discussed, we can only be optimistic regarding the future reliance of Saudi blood banks on voluntary donors. Our optimism is based on the history of voluntary blood donation drawn from our previous peacetime and wartime experiences in addition to the positive attitude and motivations of the young Saudis of both sexes. This led us to the conclusion that dependence of Saudi blood banks on 100% voluntary blood donations is possible. Attention should now be focused on forward planning at the national level, to shift the donor system from the currently partial voluntary system to a total voluntary system depending on nonremunerated donors. This entails an accurate definition of the size and nature of the needs for blood donors by each hospital blood bank, on a yearly basis, and then targeting the donor recruitment efforts to cover these needs. Subsequently, the appropriate programs need to be developed to get the donors to keep the habit. Attention should also be directed to laying down the foundation for a unified Saudi National Blood Transfusion Service to look after the future developments in blood transfusion in the KSA. All these steps should be timed according to road map and, of course, officiated by the appropriate legislation and directives from the responsible health authority, M of H.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest