Patient blood management in colorectal cancer patients: a survey among Dutch gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing awareness to integrate patient blood management (PBM) within routine surgical care. Limited information about the implementation of PBM in colorectal cancer surgery is available. This is curious, as preoperative anemia, associated with increased morbidity, is highly prevalent in colorectal cancer patients. Present study aimed to assess the current PBM strategies in the Netherlands.

METHODS

An online electronic survey was developed and sent to surgeons of the Dutch Taskforce Coloproctology (177 in total). In addition, for each hospital in which surgery for colorectal cancer surgery is performed (75 in total), the survey was sent to one gastroenterologist and one anesthesiologist. Analyses were performed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

A total of 192 physicians responded to the survey (response rate 58.7%). In 73 hospitals (97.3%) the survey was conducted by at least one physician. Regarding the management of a mild-moderate preoperative anemia, no clear policy was reported in half of the hospitals (49.3%). In 38.7% of the hospitals, iron status was indicated to be measured during screening for colorectal cancer. In addition, in only 13.3% of the hospitals, iron status was measured by the anesthesiologist during preoperative assessment.

CONCLUSION

The Present study shows a distinct variability in PBM practices in colorectal cancer care. Strikingly, this variability was not only seen between, but also within Dutch hospitals, demonstrated by often variable responses from physicians from the same institution. As a result, the present study clearly demonstrates the lack of consensus on PBM, resulting in a suboptimal preoperative blood management strategy.

ABBREVIATION

-

- PBM

-

- patient blood management.

Preoperative anemia in colorectal cancer patients is associated with an increased risk of short-term mortality and morbidity and a decrease in long-term tumor survival.1, 2 Iron deficiency is the principal cause of preoperative anemia and is reported in almost 50% of preoperative colorectal cancer patients.3, 4 Transfusion, in earlier days the default therapy to correct this anemia, however, is also known to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality, as already demonstrated by Busch and colleagues in 1993.5-9 This has resulted in alternative approaches to treat preoperative anemia, which are collectively known as patient blood management (PBM).

PBM refers to “the timely application of evidence based medical and surgical concepts designed to maintain Hb concentration, optimize hemostasis and minimize blood loss in an effort to improve patient outcome.” It has been developed to promote strategies to reduce or avoid the need of blood transfusion and therefore questions blood transfusion as the primary treatment strategy of anemia. PBM is a continuous process, initiated early in the preoperative period and continued intra- and postoperatively. Importantly, and by definition, PBM requires a multimodal and multidisciplinary strategy and should at least involve surgeons, anesthesiologists, gastroenterologists, hematologists, and nurses.10

The increasing awareness to integrate PBM within routine surgical care resulted in numerous ongoing trials studying the optimal blood management strategy in all types of surgery.11-13 To date, studies on the use and implementation of these PBM strategies are mostly limited to orthopedic and cardiac surgery.10, 14 Despite the high prevalence of preoperative anemia, associated with increased morbidity and mortality, limited information about the use and implementation of PBM strategies in colorectal cancer care is available. A review by Munoz and coworkers15 represents a clear exception to this. In this review, the prevalence and consequences of anemia are discussed and a pragmatic approach to the treatment of perioperative anemia in colorectal cancer patients is presented.

With the present study, we focused on the preoperative assessment and treatment of anemia in colorectal cancer patients and aimed to 1) assess the current preoperative blood management strategies in the Netherlands, 2) identify preferences of different physicians (surgeons, anesthesiologists, and gastroenterologists) in the treatment of preoperative anemia, and 3) evaluate physicians' general knowledge of blood management issues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

To accomplish our objectives, an online electronic survey was developed. The survey included three topics: 1) questions on the current preoperative blood management practice in colorectal cancer patients (measurement of iron variables and treatment of preoperative anemia), 2) questions on physicians' preferences in treatment of preoperative anemia (best treatment of preoperative anemia and the goal of treatment), and 3) questions to test physicians' knowledge of blood management issues. The survey questions were made by the research fellow (MJW) and two hematologists (MS and JJZ) and were subsequently tested at two sites (Department of Surgery Reinier de Graaf Hospital and Department of Anesthesiology Albert Schweitzer Hospital). The eventual revised questionnaire was sent by e-mail to the eligible participants. The online survey tool SurveyMonkey was used to conduct the survey.

Study population

After the mailing list was obtained, the survey was first sent to all surgeons of the Dutch Taskforce ColoProctology (Werkgroep Coloprotocologie) in May 2017. Subsequent e-mail reminders were sent out in July and September 2017. In addition, for each hospital in which surgery for colorectal cancer is performed (75 in total), the survey was sent to one gastroenterologist and one anesthesiologist, all involved in colorectal cancer care and usually the head of department. For this purpose, the survey was slightly modified to suit the clinical situation of the gastroenterologist and anesthesiologist. The first invitation was sent in June 2017 and subsequent e-mail reminders were sent out in July and September 2017. The participation period closed in October 2017.

Removal of undeliverable e-mails from the mailing list, as well as retired or relocated surgeons, resulted in an adjusted study population of 177 surgeons. In addition, the study population included 75 gastroenterologists and 75 anesthesiologists. As a result, the total targeted study population was 327 physicians.

Statistical analysis

Survey data were extracted into an Excel database. Statistical analyses were performed with computer software (SPSS, Version 21, SPSS, Inc.; and GraphPad Prism, Version 5, GraphPad, Inc.). Analyses were performed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Participation

As shown in Table 1, a total of 192 physicians responded to the survey (response rate, 58.7%), including 95 surgeons, 48 anesthesiologists, and 49 gastroenterologists. Of 192 respondents, 158 (82.2%) completed the survey, including 79 surgeons, 38 anesthesiologists, and 41 gastroenterologists. In total, in 73 of 75 hospitals (97.3%) one or more physicians responded to the survey. In 21 of 75 hospitals (28.0%) the survey was conducted by a surgeon, an anesthesiologist, and a gastroenterologist.

| Responses per specialism | |

| Surgeons (177 invited in total) | 95 (53.7) |

| Gastroenterologists (75 invited in total) | 49 (65.3) |

| Anesthesiologists (75 invited in total) | 48 (64.0) |

| Responses per hospital (75 in total) | |

| Surgeon(s) | 8 (10.7) |

| Gastroenterologist | 4 (5.3) |

| Anesthesiologist | 9 (12.0) |

| Surgeon(s) + gastroenterologist | 14 (18.7) |

| Surgeon(s) + anesthesiologist | 12 (16.0) |

| Gastroenterologist + anesthesiologist | 5 (6.7) |

| Surgeon(s) + gastroenterologist + anesthesiologist | 21 (28.0) |

| No response | 2 (2.7) |

- *Data are reported as number (%).

Preoperative blood management practice

Regarding the use of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions and the treatment of severe anemia, respondents from all hospitals indicated the perioperative use of a restrictive blood transfusion policy. According to the adapted 4-5-6 mmol/L hemoglobin (Hb) transfusion trigger rule (Dutch transfusion guideline), the severity of anemia and the patient-specific cardiopulmonary compensation capacity was acknowledged.16

To determine the current preoperative blood management practice per hospital, all respondents were first asked to indicate the specialist (gastroenterologist, surgeon, hematologist, anesthesiologist, unknown, or none) primarily responsible for the management of mild to moderate preoperative anemia in colorectal cancer patients. Strikingly, in 33 of 44 hospitals with multiple respondents (minimum of two physicians per hospital), these responses differed and were contradictory and needed reclassification: 1. When per-hospital multiple and different responses were given to the question who is primarily responsible for the treatment of mild to moderate anemia, the current preoperative blood management practice in the hospital was categorized as unclear/ambiguous. 2. When per-hospital multiple and different answers were given to the question whether iron variables are measured during screening for colorectal cancer, the answer of the gastroenterologist was determinant.

In 12 hospitals, an ongoing randomized clinical trial (FIT trial) during the survey period studied the efficacy of preoperative intravenous (IV) iron supplementation in comparison with preoperative oral supplementation in anemic patients with colorectal cancer.11 For these 12 hospitals, the content of the study protocol of the randomized trial was reflected in all answers regarding preoperative blood management practice.

As shown in Table 2, iron variables (iron, ferritin, transferrin, or transferrin saturation) were indicated to be measured during screening for colorectal cancer in 38.7% of all hospitals. Of these 29 hospitals, complete iron status (iron, ferritin, transferrin, and transferrin saturation) was indicated to be measured in four hospitals. In a total of 35 hospitals (46.7%), iron variables were not measured during screening. In addition to the measurement of iron variables during screening for colorectal cancer, in 10 hospitals (13.3%) iron variables were measured by the anesthesiologist at preoperative assessment, compared to 37 hospitals (49.3%) in which iron variables were not measured at preoperative assessment. In 10 hospitals (13.3%), it was indicated that anemia observed at preoperative assessment, regardless of possible previous treatment by gastroenterologist or surgeon, was treated by the anesthesiologist, compared to 34 hospitals (45.3%) in which this was not the case.

| Iron variables measured during screening colorectal cancer | |

| Answered by: gastroenterologists and surgeons | |

| Yes | 29 (38.7) |

| No | 35 (46.7) |

| Unknown/missing | 11 (14.7) |

| Treatment of anemia first started by | |

| Answered by: gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists | |

| Gastroenterologist | 11 (14.7) |

| Surgeon | 15 (20.0) |

| Colon care nurse | 4 (5.3) |

| Hematologist/internist | 2 (2.7) |

| Anesthesiologist | 2 (2.7) |

| Unclear/ambiguous policy | 37 (49.3) |

| No treatment | 1 (1.3) |

| Unknown/missing | 3 (4.0) |

| Iron variables measured at preoperative assessment anesthesiology | |

| Answered by: anesthesiologists | |

| Yes | 8 (10.7) |

| No | 37 (49.3) |

| Unknown/missing | 30 (40.0) |

| Treatment of anemia by anesthesiologists, regardless of previous treatment | |

| Answered by: anesthesiologists | |

| Yes | 10 (13.3) |

| No | 34 (45.3) |

| Unknown/missing | 31 (41.3) |

- *Data are reported as number (%).

Regarding the treatment of preoperative anemia, respondents from 19 hospitals (25.3%), including the 12 hospitals participating in the ongoing FIT trial, indicated that the surgeons or colon care nurses were primarily responsible (Table 2). In 11 hospitals (14.7%) the gastroenterologist was the first responsible to treat a mild to moderate preoperative anemia. In two hospitals each (2.7%), hematologists and anesthesiologists were indicated as primarily responsible for treatment, while in one hospital (1.3%) it was indicated that a mild to moderate preoperative anemia was not treated. In only four hospitals, the treatment of preoperative anemia was reported to be part of a protocol, with the aim of optimizing the preoperative condition of a patient. In half of the hospitals (49.3%), no clear policy regarding the treatment of preoperative anemia was reported. In 44 hospitals multiple responses (minimum of two physicians per hospital) to the question regarding the treatment of preoperative anemia were given, and in 33 hospitals (75.0%) these responses differed and were contradictory.

Objectives for treatment of preoperative anemia

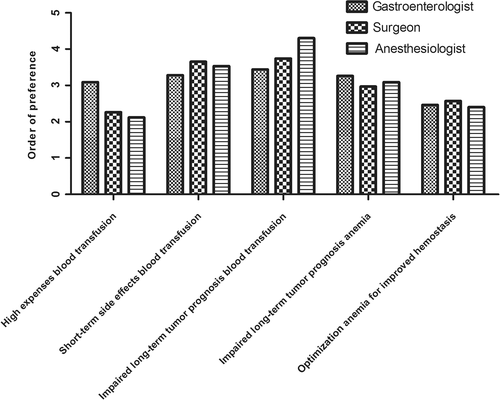

All respondents were asked to prioritize their objectives for treatment of preoperative anemia. Results are shown in Fig. 1. Pooled responses demonstrated that “prevention of blood transfusion, because of its association with impaired long-term tumor prognosis” was ranked first, followed by “prevention of blood transfusion, because of its short-term side effects”; “prevention of preoperative anemia, because of its association with impaired long-term tumor prognosis”; “prevention of blood transfusion, because of its high expenses”; and “optimization of preoperative Hb level for enhanced hemostasis.” This order of preference was similar for the different specialisms.

Decision making in treatment preoperative anemia

Table 3 provides percentages of respondents considering different variables in their decision to treat preoperative anemia. Only respondents who had indicated to treat preoperative anemia themselves were asked this question. Overall, “age of patient” was considered by 63.3% of all respondents, “presence of iron deficiency” by 75.5%, “presence of clinical symptoms of anemia” by 85.7%, “presence of comorbidities” by 83.7%, and “severity of anemia” by 98.0%.

| Gastroenterologists | Surgeons | Anesthesiologists | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Variables considered in decision making in treatment of preoperative anemia | ||||

| Age of patient | 16 (76.2) | 12 (66.7) | 3 (30) | 31 (63.3) |

| Presence of iron deficiency | 19 (90.5) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (50) | 37 (75.5) |

| Presence of clinical symptoms of anemia | 20 (95.2) | 14 (77.8) | 8 (80) | 42 (85.7) |

| Presence of comorbidities | 18 (85.7) | 15 (83.3) | 8 (80) | 41 (83.7) |

| Severity of anemia | 21 (100) | 17 (94.4) | 10 (100) | 48 (98) |

| B. Type of treatment (oral or IV iron) is dependent on type of iron deficiency (absolute vs. functional iron deficiency) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (30) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (50) | 8 (44.4) |

| No | 7 (70) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (50) | 10 (55.6) |

| C. First choice of treatment in case of an absolute iron deficiency anemia | ||||

| Oral iron | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (28.6) |

| IV iron | 3 (100) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 5 (71.4) |

| D. First choice of treatment in case of a functional iron deficiency anemia | ||||

| Oral iron | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

| IV iron | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) |

- *Data are reported as number (%).

In case respondents indicated that their decision to treat anemia is dependent on the presence of iron deficiency, they were asked if the iron formulation (oral or IV) would depend on the type of iron deficiency (absolute vs. functional iron deficiency) and, if so, what treatment was chosen for an absolute and a functional iron deficiency anemia. Absolute iron deficiency is characterized by depleted iron stores (defined by decreased transferrin saturation and increased transferrin), while functional iron deficiency is caused by impaired iron homeostasis and is, due to increased hepcidin production, characterized by reduced iron uptake and iron mobilization from the reticuloendothelial system (defined by decreased transferrin saturation and increased ferritin). For a small minority of respondents (44.4%) the type of iron deficiency made a difference for their treatment. In case of an absolute iron deficiency anemia, IV iron was the first choice of treatment for 71.4% of these respondents (vs. 28.6% oral iron). In case of a functional iron deficiency, the choice of treatment was equally divided (50% oral iron vs. 50% IV iron).

Contraindications to IV iron therapy

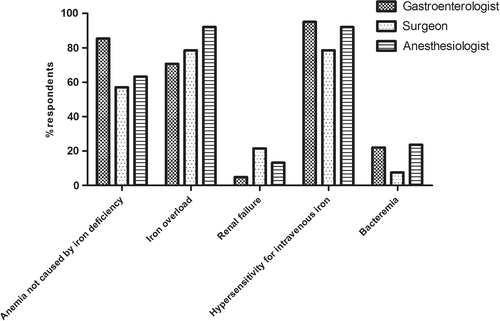

Figure 2 provides the percentages of respondents identifying different variables as an absolute contraindication to IV iron therapy. Overall, contraindications to IV iron therapy included “anemia not caused by iron deficiency” for 65.8% of all respondents, “iron overload” for 79.7%, “hypersensitivity for IV iron” for 86.1%, and “bacteremia” for 15.2%. “Renal failure” was indicated as an absolute contraindication by 15.2% of all respondents. Surgeons, gastroenterologists, and anesthesiologists (78.5, 92.1, and 95.1%, respectively) most frequently identified hypersensitivity for IV iron as absolute contraindication. Gastroenterologists and anesthesiologists (4.9 and 13.2%, respectively) least frequently indicated renal failure as absolute contraindication, while surgeons least frequently indicated bacteremia in this regard (7.6%).

International guidelines on the long-term effects of iron therapy

Overall, 8.9% of the respondents indicated to believe that the long-term oncologic effects of IV iron therapy are known and already incorporated in the international guidelines on the treatment of anemia in cancer patients. A total of 5.7% of the respondents indicated to regard IV iron as safe, while in contrast 3.2% of respondents believed IV iron therapy to be associated with impaired long-term tumor prognosis. A total of 22.2% of the respondents indicated that the long-term oncologic effects of IV iron therapy are not studied and therefore not included in the international guidelines. A vast majority (69%) indicated to be ignorant on this subject.

DISCUSSION

The results of our national survey show a distinct variability in preoperative blood management practices in colorectal cancer patients. Strikingly, this variability is not only found among hospitals, but also within hospitals, demonstrated by variable responses from gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists from the same institution. As a result, this study clearly demonstrates the lack of consensus on PBM among gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists, resulting in a suboptimal preoperative blood management strategy.

Extensive research on barriers limiting the translation of PBM into clinical practice has led to simplified international recommendations for the implementation of PBM.17-21 One of these recommendations is that each hospital should appoint a key leader for the PBM project management, who should have a central role in charge of communication, education, and documentation. This should contribute to a more clear division in responsibilities among treating physicians. Our study clearly demonstrates that this is not the case for the vast majority of Dutch hospitals. Most gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists referred to different persons they held primarily responsible for the treatment of a mild to moderate preoperative anemia in colorectal cancer patients. In the few hospitals practicing preoperative blood management according to protocol, the persons primarily responsible were clear for all respondents.

A second simplified recommendation is derived from the fact that effective correction of anemia will depend on the underlying disorder and states that optimal PBM should involve screening for the underlying cause, preferably at the earliest opportunity to allow optimal correction. With respect to this recommendation, our study again showed a high variation to which extent anemia and underlying causes were investigated and identified. In only 38.7% of hospitals, iron variables, essential for identifying type of anemia, were indicated to be measured during screening for colorectal cancer (by gastroenterologist or surgeon). In addition, in only 13.3% of hospitals, iron variables were measured by the anesthesiologist during preoperative assessment. Most strikingly, anemia is, regardless of previous treatment by surgeon or gastroenterologists, treated by the anesthesiologist in only a quarter of the hospitals. These results clearly indicate that the majority of the Dutch hospitals are failing in the assessment and treatment of preoperative anemia.

A third recommendation is that both physicians and nurses need to be trained in PBM clinical protocols and transfusion algorithms. According to our results, much progress could be made by improving the knowledge of physicians on these subjects. For example, in case of a functional iron deficiency, the choice of treatment was equally divided between oral and IV iron. This is a striking and counterintuitive result, as oral iron is known to be nearly inefficacious in patients with a functional iron deficiency. In addition, the results of the acknowledgment of contraindications to IV iron emphasize the knowledge gap of the responding physicians. Renal failure, the commonest indication for IV iron therapy, was considered as an absolute contraindication by up to 15.2% of all respondents. Anemia not caused by iron deficiency and iron overload, which are clear contraindications to IV iron therapy, were indicated as such by only 66 and 80% of all respondents, respectively. Hypersensitivity for IV iron is the most dangerous contraindication and acute hypersensitivity reactions during infusion are very rare but can be life-threatening. A review by Rampton and coworkers22 provides recommendations about their management and prevention. Importantly, if IV iron is to be given to individuals with any of the risk factors for acute hypersensitivity reactions (previous reaction to an iron infusion, a fast iron infusion rate, multiple drug allergies, severe atopy, systemic inflammatory diseases), an extremely slow infusion rate and meticulous observation is recommended. Finally, and notwithstanding the observed knowledge gap on PBM issues, possible long-term and potential hazardous effects of iron therapy in colorectal cancer patients are still unclear. Therefore, the long-term effects of iron therapy are not discussed in regard to the most optimal preoperative blood management strategy. Uncertainty on the potential role of iron in tumor progression arises from epidemiologic and nonclinical studies, showing iron's role in all aspects of cancer development and cancer growth.23-27 Despite the fact that the conditions in these epidemiologic and nonclinical studies often do not reflect the clinical situation in anemic patients and often use excessive iron doses in iron-replete animals, we believe that well-designed clinical studies are required to exclude the potential long-term hazardous effect of iron therapy in cancer patients.

The increasing awareness to integrate PBM within routine surgical care has resulted in numerous completed and ongoing trials studying the optimal blood management strategy in all types of surgery.11, 13, 28, 29 With regard to colorectal cancer, a pragmatic approach to the management of perioperative anemia is presented by Munoz and colleagues.15 In this review, the use of PBM is strongly advocated to minimize or eliminate the use of allogeneic blood transfusion. Regarding the treatment of perioperative anemia, the use of oral iron is clearly dissuaded as it is poorly tolerated with low adherence based on published evidence, while the use of IV iron is strongly advised as it is safe and effective, but also frequently avoided due to misinformation and misinterpretation concerning the incidence and clinical nature of minor infusion reactions. In addition to this review and regarding the efficacy of IV iron therapy, a study by Keeler and colleagues12 showed that IV iron is more effective in increasing Hb level compared to oral iron, but did not observe a relevant difference in the administration of RBC transfusions. However, in this trial the sample size was small and only primary outcomes in terms of increasing Hb level and the use of RBC transfusions were reported, stressing the need for larger trials with a focus on functional performance and quality of life.11 The results of such trials should provide more evidence surrounding the effectiveness of the management of preoperative anemia and should contribute to successful implementation of PBM protocols, specifically in colorectal cancer patients.

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of our study is the availability of responses from gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists. This enables comparison between different medical disciplines within and between hospitals. Our data set allows assessing the knowledge of the different types of physicians and assessing the consensus in the management of preoperative anemia. In addition, in all hospitals except two, at least one physician responded to the survey. While the availability of responses from gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists is a key strength of our study, it also appeared to be a limitation. Due to the high variety in responses, it was extremely difficult to determine the actual preoperative blood management strategy per hospital. An additional limitation of our study is that it is a national survey, hampering generalization of our results to an international setting. However, the Netherlands are known to be a pioneer in the implementation of PBM, using PBM strategies for more than two decades, especially for major orthopedic surgery.10 Therefore, in other countries, physicians' knowledge of blood management issues and implementation of PBM in colorectal cancer care will presumably not be superior to the Dutch setting.

CONCLUSION

This study shows a distinct variability in preoperative blood management practices in colorectal cancer care. Strikingly, this variability, which was not only seen among but also within Dutch hospitals, was demonstrated by variable responses from gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists from the same institution. As a result, this study clearly demonstrates the lack of consensus on PBM among gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists, resulting in a suboptimal preoperative blood management strategy. For a more effective and uniform implementation of PBM, much progress could be made on education as this study clearly demonstrates a significant information deficit among physicians dealing with PBM issues. In addition, results of clinical trials providing evidence surrounding the effectiveness of treatment of preoperative anemia should contribute to more evidence-based guidelines. Finally, appointing key leaders for PBM project management should contribute to improved communication and cooperation, resulting in a more clear division in responsibilities among treating physicians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.