Depression and cognitive deficits as long-term consequences of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

TF and VS are joint first authors.

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is an acute life-threatening microangiopathy with a tendency of relapse characterized by consumptive thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and spontaneous von Willebrand factor–induced platelet clumping leading to microthrombi. The brain is frequently affected by microthrombi leading to neurologic abnormalities of varying severity.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

The aim of this observational cohort study was to investigate the prevalence of depression and cognitive deficits in 104 patients having survived acute TTP. TTP survivors were repeatedly assessed by means of different standardized questionnaires to evaluate depression (IDS-SR) and mental performance (FLei). We received answers of 104 individual TTP patients and 55 of them participated in both surveys.

RESULTS

Seventy-one of the 104 responding TTP patients (68%) suffered from depression and the severity of depression was similar in both surveys performed 1 year apart. Furthermore, TTP patients had considerably lower cognitive performance than controls. There was no correlation between prevalence of depression and cognitive deficits and the number and the severity of acute episodes. Impairment of mental performance correlated with the severity of depression (rs = 0.779).

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of depression and cognitive deficits was significantly higher in TTP patients. Cognitive impairment seemed to be a consequence of depression, almost independently of number and severity of TTP episodes.

ABBREVIATIONS

-

- FLei

-

- German questionnaire for complaints of cognitive disturbances

-

- IDS-SR

-

- Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Self-Report

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- TTP

-

- thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is an acute, life-threatening disorder that is characterized by widespread von Willebrand factor (VWF)- and platelet (PLT)-rich microthrombi involving capillaries and arterioles of the brain and other organs.1 Further characteristics are thrombocytopenia due to consumption of PLTs and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with destruction of red blood cells.2 The most common form of TTP is caused by inhibitory autoantibodies to the VWF-cleaving protease ADAMTS13.1-3 Patients surviving an acute TTP bout and showing normalization of the laboratory variables are often considered to be cured; however, recurrences of acute TTP attacks are common.4 In recent years the long-term consequences of this disease were noted because in spite of normal laboratory data, many TTP patients complained of neuropsychological deficits. Some studies showed that these patients had a significantly lower quality of life in comparison to the population.5-7 In addition, many TTP patients suffer from cognitive deficits and depression.5, 8-10 Until now, few studies regarding neuropsychological consequences of TTP have been published. An increased prevalence of depression among patients with somatic diseases is known. Many studies have shown an increased prevalence of depressive symptoms among people after stroke, myocardial infarction, or certain autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis.11-17

In this study we investigated the prevalence of depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits in patients having survived acute TTP episodes. We undertook two surveys at an interval of 1 year to investigate possible changes over time and risk factors. The latter included the number and severity of TTP episodes, the incidence of stroke, and the occurrence of neurologic symptoms during TTP bouts, which could promote neuropsychological problems. The early identification of depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits may be important to provide the best care for the patients and to improve their quality of life.18, 19

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The University Medical Center Mainz is a government-funded major referral center for TTP patients. Those living in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate were treated in the Department of Hematology, Oncology and Pneumology of University Medical Center Mainz and were directly included in this observational cohort study. In addition, this study includes all consecutive TTP patients for whom the major referral center Mainz was requested to give medical advice to the external hospitals. External TTP patients presented personally, usually once per year, in the Department of Hematology, Oncology and Pneumology of University Medical Center Mainz.

Patients

The study was initiated in October 2012 and since then all patients were prospectively registered, who had been treated for acute TTP and/or followed in remission at least once per year by the department of Hematology, Oncology and Pneumology at the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University. After the approval of the ethics committee was obtained, TTP patients were interviewed once per year by means of standardized questionnaires. The first inquiry was conducted in June 2013 and the second in July 2014 including all patients aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of TTP before starting this study and who were in remission (normal PLT count for at least 30 days after the last plasma exchange). During the course of this study, further participants with an incident diagnosis of TTP were recruited. Inclusion criteria were the clinical diagnosis of TTP, defined as a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia (<150 × 109/L), and severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (<10%) in acute TTP episode. ADAMTS13 activity was measured either with a commercial FRETS-assay developed by American Diagnostica, Inc. (ACTIFLUOR ADAMTS13) or since July 2014 by a fluorogenic assay using the FRETS-VWF73 substrate.20, 21

Results of questionnaire study were related to the number and severity of acute TTP episodes and to the time interval between the last acute TTP bout and the survey. Therefore, past clinical history of TTP patients was collected retrospectively by means of medical records and prospectively since October 2012. Clinical reports of all TTP patients were examined regarding course of disease, especially neurologic symptoms during acute episodes and relapse rate. TTP-induced neurologic abnormalities were defined as presenting features if they occurred at any time during the acute episode. Neurologic signs were graded as severe, mild, or absent as reported by Vesely and colleagues.22 The process of patients' recruitment is shown in Fig. 1. Demographic and clinical details are presented in Table 1. Additionally, healthy adults were interviewed during the second survey as a control cohort including employees and associated persons of the University Medical Center Mainz as well as students of all departments of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, who did not have TTP, cancer, coronary heart disease, or neurologic disorder. These controls were about 10 years younger and the proportion of females was lower compared to the TTP patient group (Table 2). For this reason we used a linear regression model as sensitivity analysis to compare the patients and controls in both surveys for both outcome variables German questionnaire for complaints of cognitive disturbances (FLei) score and Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Self-Report (IDS-SR) score to adjust for age and sex. The p values do not differ compared to the p values from the univariable tests for comparing patients and controls. Furthermore, results of FLei were compared with those of healthy controls (n = 97) as well as depressive patients (n = 94) from the literature.23 The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of “Landesärztekammer Rheinland-Pfalz” [837.265.14 (9504-F)], and all participants had given written consent to participation.

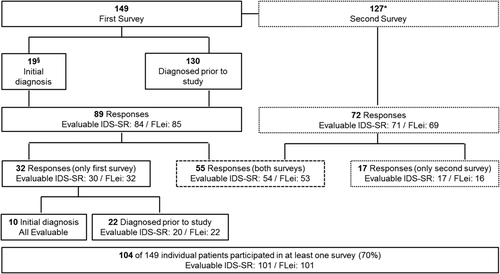

Patient recruitment and response rates in two surveys of the cohort of TTP patients from Mainz. A total of 149 eligible TTP patients in remission were invited to fill out two questionnaires used in two surveys each. A total of 130 of the 149 patients had been diagnosed with TTP before starting this study whereas 19 patients had their initial diagnosis of TTP during this study. *Between the first and second surveys two of the 130 invited patients died from a cause unrelated to TTP and one patient was lost to follow-up. §The 19 patients newly diagnosed during the first survey were not yet subjected to the second survey. Accordingly, 127 TTP patients were sent the questionnaires in the second survey after approximately 1 year. Response rates and number of evaluable questionnaires are indicated.

| Characteristics | TTP patients first survey | TTP patients second survey | Healthy controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 85 | 71 | 52 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 68 (80) | 60 (85) | 31 (61) |

| Male | 17 (20) | 11 (15) | 20 (39) |

| Age (years) | 46 (18-84) | 45 (22-85) | 35 (21-87) |

| Psychotherapy | |||

| Before TTP diagnosis | 9 (11) | NA | 11 (21) |

| After TTP diagnosis | 17 (20) | NA | Not applicable |

| At the time of questioning | 6 (7) | 6 (8) | 3 (6) |

| Psychopharmacotherapy | NA* | 10 (14) | NA* |

- a Data are reported as number (%) or median (range).

- NA = not available.

| TTP patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test domain | First survey | Second survey | Healthy controls | Healthy controls23 | Depressive controls23 |

| Number | 85 | 69 | 52 | 97 | 94 |

| Total FLei score | 38.8 (±26.2)a,b | 37.5 (±26.2)a,c | 16.7 (±10.8) | 29.1 (±18.7) | 56.5 (±23.1) |

| Subscores memory | 13.9 (±9.1)a,c | 13.8 (±9.1)a,c | 7.2 (±4.3) | 10.8 (±6.6) | 18.3 (±7.9) |

| Attention | 13.5 (±9.6)a,b | 12.9 (±9.8)a,c | 4.8 (±3.6) | 9.7 (±6.5) | 19.2 (±8.4) |

| Executive function | 11.5 (±8.5)a,c | 10.8 (±8.5)a,d | 4.7 (±4.1) | 8.7 (±6.7) | 19.0 (±8.5) |

- a Total score points and subscores for memory, attention, and executive function [mean (±SD)] in TTP patients, in comparison to our healthy controls, as well as to healthy and depressive controls from the literature.23 Mental performance was significantly worse for TTP patients in each survey in comparison to both healthy cohorts (bp < 0.001, cp < 0.01, and dp < 0.05). TTP patients performed significantly (ap < 0.001) better than the depressive controls from the literature.

Psychometric assessment

TTP patients were twice invited to participate in the study at an interval of 10 to 12 months. At both time points, psychometric questionnaires were either sent by regular mail to the patients' home or given directly to patients before discharge from hospital. We used standardized questionnaires to evaluate depression (IDS-SR)24, 25 and mental performance comprising executive function, memory, and attention (FLei, “Fragebogen zur subjektiven Einschätzung der geistigen Leistungsfähigkeit”).23

IDS-SR

Depression was assessed by the German version of the IDS-SR. The IDS-SR consists of 30 items assessing the presence and severity of symptoms and detecting changes of symptoms during acute phase treatment.25 Each of the 30 items is rated by a score from 0 to 3 with increasing severity represented as a higher score.24 The total score ranges from 0 to 84 and is interpreted as follows: 0-13: no depression; 14-25: mild depression; 26-38: moderate depression; 39-48: severe depression; 49-84: very severe depression. The IDS-SR is one of the few validated questionnaires that deliver comparable results when used for self-diagnosis and as an assessment tool for the physician. This test is well suited to detect symptoms of depression and any changes occurring during the course of the depression. A comparison of the IDS-SR with other standardized questionnaires shows good agreement for grading the severity of depression.25 Comparing the widely used Beck Depression Inventory to the IDS-SR suggests that a clinically relevant depression can be confidently diagnosed for depression score of more than 25 on the IDS-SR.24, 25

FLei

Cognitive deficits were assessed by the FLei, a self-report measure with 30 items covering the subscores of deficient attention, memory, and executive functions, with 10 items each. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = at no time; 4 = very frequent). Accordingly, total score for all 30 items ranges between 0 and 120 points. The internal consistencies of the three subscores (Cronbach's alpha and split-half reliability) are all more than 0.87.23 Healthy controls reported in the literature showed a mean of 29.1 (standard deviation [SD] ± 18.7) whereas controls with major depression (ICD.10) had a mean of 56.5 (SD ± 23.1; Table 2).23

Covariates

Age, sex, and clinical characteristics including time interval since the last acute TTP episode, total number of TTP bouts, presence or absence of neurologic symptoms during the acute TTP attacks, and occurrence of stroke were obtained from medical records. Information concerning psychotherapy and antidepressive medication was collected by questioning the participants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using computer software (SPSS, Version 22.0, IBM GmbH). Descriptive statistics included frequency, mean, SD, median, interquartile range (IQR), minimum, and maximum. Differences between two groups were tested using t test for normally distributed data and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for nonnormally distributed outcomes, as well as the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparing patients with one versus two versus three or more TTP episodes. As the patient and control groups differ in age and sex distribution, a linear regression model was additionally used for comparing the FLei score between the patient and the control group to adjust for age and sex. For comparing changes in FLei score between patients, who completed the first and second surveys, a dependent t test was used as well as for the IDS-SR score the dependent Wilcoxon test. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (rs) were calculated to estimate the relationships between depressive symptoms or cognitive deficits, respectively, and the number of TTP episodes and to estimate the relationship between depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits. p values less than 0.05 were considered as significant. All p values should be treated with caution as no adjustment for multiple testing was performed.

RESULTS

Study population

From June 2013 until November 2014, a total of 148 patients with a clinical diagnosis of an acquired TTP, one with a hereditary TTP, and 52 healthy controls were asked to participate. A total of 130 of the 149 patients had been diagnosed with TTP before starting this study and were in remission at the time of investigation. Nineteen patients had their initial diagnosis of TTP during this study; they were evaluated in the first survey after achieving remission (Fig. 1). Between the first and second surveys, two of the 130 participants having been diagnosed with TTP before starting the study died from a cause unrelated to TTP and one patient was lost to follow-up. The 19 patients newly diagnosed during and after the first survey were not yet subjected to the second survey. Accordingly, 127 TTP patients were sent the questionnaires in the second survey, approximately 1 year after the first inquiry.

We received 89 responses in the first survey, 85 of which were evaluable for FLei and 84 for IDS-SR (Fig. 1). Seventy-two responses were obtained in the second survey, 69 were evaluable for FLei and 71 for IDS-SR. Overall, responses of 101 individual TTP patients were evaluable for IDS-SR and FLei, respectively, and 54 IDS-SR and 53 FLei questionnaires were evaluable for both the first and the second surveys. Thirty-two TTP patients participated only in the first survey and 17 only in the second survey (Fig. 1). Results of impairment of cognitive performance (FLei) of the TTP patients were compared with FLei scores of 97 healthy controls as well as 94 patients with diagnosed depression (ICD-10) from the literature23 (Table 2).

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the TTP patients and the healthy controls are shown in Table 1. Participants were predominantly female (first survey 80% females, second survey 85% females) with a mean age of approximately 45 years spanning a wide range from 18 to 85 years. Fifty-five percent of the TTP patients had children, 31% were single, 58% were married, and 11% were divorced. Fifty-one percent of TTP patients stated that they have distress. Forty-eight percent of the TTP cohort were overweight (body mass index > 25). Medical records of 60 of the 104 individual TTP patients were completely evaluable regarding neurologic symptoms during acute episodes and relapse rate.

IDS-SR results

In 2013, a total of 61 (72.6%) of 84 TTP patients were scored to have current depressive symptoms by IDS-SR (score points ≥14). The median evaluated score points were 20 (IQR, 12-34), ranging from 0 to 59 (Fig. 2A). Twenty-three (27.4%) patients had no, 27 (32.1%) had mild, 22 (26.2%) had moderate, six (7.1%) had severe, and six (7.1%) had very severe depression.

Results of depression (IDS-SR) and cognitive impairment (FLei) of TTP patients in the two surveys and of the healthy controls. (A) IDS-SR score for the TTP patients at the first (n = 84) and at the second surveys (n = 71) compared to healthy controls (n = 52). For the first survey the median evaluated score points were 20 (IQR, 12-34), for the second survey 18 (IQR, 9-33), and for the healthy controls 7 (IQR, 4-9). The prevalence of depressive symptoms in TTP patients was significantly higher in both surveys than in controls (p < 0.001 each). (B) FLei score for the TTP patients at the first (n = 85) and at the second surveys (n = 69) in comparison to healthy controls (n = 51). For the first survey the median evaluated score points were 35.5 (IQR, 15-60), for the second survey 33 (IQR, 15-60), and for the healthy controls 15 (IQR, 9-24). Mental performance was significantly worse for TTP patients in both surveys in comparison to the healthy controls (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively).

At first survey, 20% of the patients stated having received psychotherapy after being diagnosed with TTP, 11% had received psychotherapy before the diagnosis of TTP, and 7% were receiving psychotherapy at the time of answering the questionnaire (Table 1). In 2014, 42 (59.2%) of 71 TTP patients were scored to have current depressive symptoms by IDS-SR (score points ≥14). The median total score was 18 (IQR, 9-33), ranging from 0 to 61 score points (Fig. 2A). Regarding severity of depression, 29 (40.8%) patients had no, 15 (21.1%) had mild, 19 (26.8%) had moderate, five (7.0%) had severe, and three (4.3%) had very severe depression.

At the time of questioning six (8%) TTP patients received psychotherapy and 10 (14%) were treated with antidepressants (Table 1). Seven of 52 (13.5%) healthy controls had score points suggesting depressive symptoms (score points ≥ 14; Fig. 2A). None of these 52 had a clinically relevant depression (>25). This prevalence of mild depression in controls complies with the 12-month prevalence in Germany (9.3% total, 6.1% in men, and 12.4% in women) as well as with the expected prevalence in the United States (6%).9, 26

The prevalence of depression in TTP patients was significantly higher in both surveys than in controls (p < 0.001). No differences concerning prevalence and severity of depression between the TTP patients in both surveys was detected.

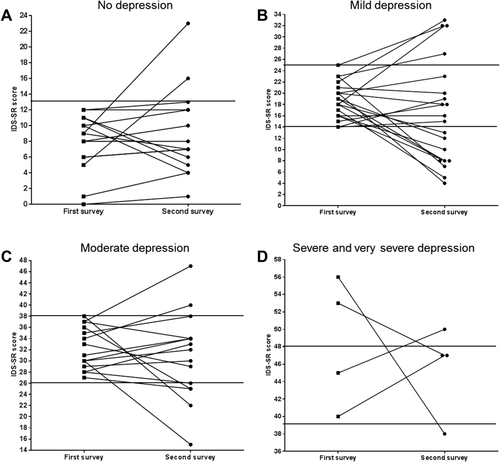

Fifty-five TTP patients responded both in the first and in the second surveys and 54 of them were evaluable for IDS-SR twice. The severity of depression for most of these patients was similar in both surveys (Fig. 3). Most of the 19 TTP patients with clinically relevant depressive symptoms (IDS-SR score > 25) in the first survey had no improvement; only four cases with clinically relevant, moderate, depressive symptoms improved (Figs. 3C and 3D). On the other hand, TTP patients with no or mild depressive symptoms did not develop clinically relevant depressive symptoms in most instances; only four of 35 TTP patients with no or mild symptoms developed a moderate depression (Figs. 3A and 3B).

Course of depression in 54 TTP patients with evaluable IDS-SR scores in both first and second surveys. (A) Fifteen TTP patients with no depression (score points, 0-13) in the first survey. (B) Twenty TTP patients with mild depression (score points, 14-25) in the first survey. (C) Fifteen TTP patients with moderate depression (score points, 26-38) in the first survey. (D) Two TTP patients with severe (score points, 39-48) and two with very severe depression (score points, 49-84) in the first survey.

FLei results

Eighty-five TTP patients in the first and 69 in the second surveys were evaluable for their mental performance by FLei (Fig. 2B). The total score points in both surveys were normally distributed and showed a mean of 38.8 (SD ± 26.2) in the first and a mean of 37.5 (SD ± 26.2) in the second survey, ranging from 0 to 108 (Fig. 2B, Table 2). Mental performance, as well as the three subscores, were significantly worse for TTP patients in both surveys in comparison to both healthy cohorts (Table 2). Nevertheless, TTP patients performed significantly (p < 0.001) better than depressive patients from the literature (Table 2). The comparison of the FLei results for the 53 TTP patients who were evaluable in both surveys showed nearly identical mental performance scores (data not shown).

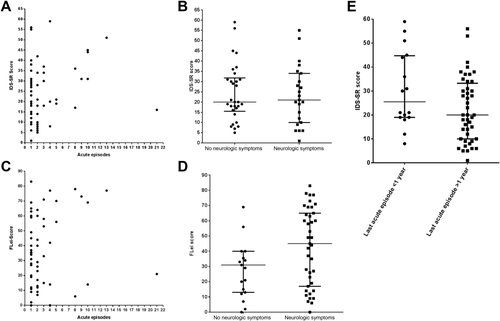

Association of depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits with number and severity of acute TTP attacks

The exact course of disease could be ascertained for 60 of 104 (58%) patients for whom all clinical records were available. These patients were selected to assess the relation of IDS-SR and FLei to characteristics of TTP. We evaluated the time since the initial TTP diagnosis, the number of TTP bouts, the time span since the last acute episode of TTP, and the symptoms during acute disease. We found no positive correlation of presence or severity of depression (first survey rs = 0.157; second survey rs = 0.023) or cognitive deficits (first survey rs = 0.115; second survey rs = 0.092) and the number of survived acute episodes (Figs. 4A and C). Solely in the first survey, TTP patients with one acute bout were less depressive than patients with two and more acute bouts (Kuskal-Wallis test p = 0.011). Similarly, IDS-SR (55 patients first survey, p = 0.466, Fig. 4B; 48 patients second survey, p = 0.367, not shown) and FLei (56 patients first survey, p = 0.193, Fig. 4D; 47 patients second survey, p = 0.793, not shown) were not significantly different in patients having suffered from neurologic symptoms compared to those without neurologic manifestation. Nine patients had suffered a stroke in their clinical history. Six of them had an IDS-SR score of more than 25 and a mean value of 72 (range, 36-93) in the FLei score. Furthermore, we investigated the correlation between depression (Fig. 4E) and cognitive deficits (not shown), respectively, and the time interval since last acute episode until survey. Sixteen (27%) TTP patients had their last acute episode within the past year and 44 (73%) more than 1 year before the inquiry. A trend was detectable that patients with a most recent TTP episode within the past year had higher depression scores (median, 26; IQR, 19-45) than patients with no bout in the past year (median, 20; IQR, 10-33; p = 0.063; NS). In summary, no significant correlation between severity of depression or magnitude of cognitive deficits and the frequency or the severity of acute TTP episodes, respectively, was detectable.

Association of depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits with number and severity of acute TTP attacks. (A) Correlation between IDS-SR score and the number of acute TTP episodes (median, 1) in the first survey (rs = 0.157, NS) for 57 evaluable TTP patients. Comparison of TTP patients with one versus two versus three and more acute episodes (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.011). (B) In the first survey 30 TTP patients (IDS-SR median, 20 [IQR, 16-32]) had no and 23 TTP patients (IDS-SR median, 21 [IQR, 10-34]) had neurologic symptoms in the last acute TTP episode. There was no difference between severity of depression in patients with or without neurologic symptoms (Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.781, NS). (C) Correlation between cognitive deficits (FLei score) and the number of acute TTP episodes (median, 1) in the first survey (rs = 0.115, NS) for 58 evaluable TTP patients. Comparison of TTP patients with one versus two versus three and more acute episodes (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.078). (D) Cognitive deficits and presence or absence of neurologic symptoms during any acute TTP episode in the first survey. Median FLei score in 17 TTP patients without neurologic symptoms was 31 (IQR, 13-40), and median FLei score in 39 patients with neurologic symptoms was 45 (IQR, 15-65; Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.193, NS). (E) IDS-SR score for the TTP patients with an acute TTP episode within the past year (n = 16) in comparison to those with the last TTP attack more than 1 year ago (n = 44; Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.063, NS).

Correlation of depression and impaired cognitive performance

Impaired mental performance correlated strongly with the severity of depression (Fig. 5). Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (rs) for 84 TTP patients in the first survey was 0.643 (p < 0.001; Fig. 5A) and for 69 participants in the second survey 0.779 (p < 0.001; Fig. 5B). Overall, correlation of FLei and IDS-SR from 101 individual TTP patients revealed an rs of 0.696 (p < 0.001). TTP patients without clinically relevant depression (IDS-SR ≤ 25) had FLei scores (mean first survey, 26.4; mean second survey, 23.2) not different to healthy controls (mean, 29.1; Fig. 5). TTP patients with clinically relevant depression (IDS-SR score > 25) had FLei scores (mean first survey, 56.6; mean second survey, 61.0) not different from depressive controls (mean, 56.5; Fig. 5). TTP patients with severe and very severe depression performed slightly, not significantly, worse in the FLei score than depressive patients from the literature (Table 2).

Correlation of FLei score with IDS-SR score. (A) Correlation of FLei and IDS-SR in the first survey of 84 TTP patients (rs = 0.643, p < 0.001). (B) Correlation of FLei and IDS-SR in the second survey of 69 TTP patients (rs = 0.779, p < 0.001). Clinically relevant depression (IDS-SR score > 25) is indicated by a vertical line.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of TTP currently focuses on survival of acute episodes, the mortality still being approximately 10% to 20%.4 Possible long-term consequences of TTP have not been given major attention until recently. The prevalence of depression in survivors of TTP in our surveys exceeds the 12-month prevalence in the German general population (9.3%), in women (12.4%) and in men (6.1%).26 Deford and colleagues9 reported a point prevalence of 19% for major depression, which is significantly higher than in the local population and similar to the prevalence of severe and very severe depression together (14 and 11%, respectively, in the two surveys of our patients). Focusing on all patients with clinically relevant depression (IDS-SR > 25) we observed 40% in the first and 38% in the second surveys. These results are consistent with the report of Han and coworkers27 who reported a point prevalence of 46% for clinically relevant depression investigating 35 TTP patients assessed by Beck Depression Inventory. Other severe diseases, both acute and chronic, are associated with an increased rate of depression. Autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis,16, 28 which progress with relapses, or systemic lupus erythematodes are associated with a high prevalence of depression.27 Depression also frequently occurs after a myocardial infarction29 or stroke.13, 30, 31 Depressive symptoms can contribute to impaired quality of life and herald an unfavorable prognosis of the original disease including an increased morbidity and mortality.9, 18, 19 Lewis and coworkers6 investigated the quality of life in 118 and Cataland and coworkers5 in 27 TTP patients by using the SF-36 questionnaire. These patients exhibited a significant decrease in quality of life compared to the general population. To assess the patients' everyday impairment, we decided to use the subjective FLei questionnaire, which encompasses tests for memory, attention, and executive function. Our TTP patients reported a significant reduction of their cognitive performance compared with healthy controls; however, they performed significantly better than depressive controls reported from the literature.23 This is in line with findings of Kennedy and colleagues8 as well as Cataland and colleagues5 who described impaired cognitive performance, albeit both groups used clinical evaluation methods instead of self-reports. The significant correlation between severity of depression and the degree to which cognitive performance was reduced raises the question whether impaired cognitive performance is a direct consequence of depression rather than a result of prior cerebral microvascular thrombosis and ischemia. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that TTP patients who did not suffer from clinically relevant depression performed at least equally well in FLei as healthy controls, independently of severity and number of prior acute TTP episodes. TTP patients with severe or very severe depression perform identically to depressive cohorts reported in the literature.23 An association of depression and relevant cognitive problems is described in the literature.32, 33 Kennedy and colleagues8 suggested that the cognitive impairment might result from the diffuse cerebral microvascular thrombosis. On the other hand, Han and coworkers27 found no relationship between depression and cognitive performance in TTP survivors; however, they compared the Beck Depression Inventory, a questionnaire for self-evaluation of depression, with a psychiatric assessment of cognitive performance. Thus, the results of Han and colleagues27 support our hypothesis that self-estimated cognitive impairment may primarily be ascribed to depression. The degree to which reduction in cognitive performance is caused by microvascular thrombosis during acute bouts of TTP and to which extent impaired cognitive performance is a direct result of depression is unclear and needs further prospective investigation.

Our study has limitations: first, our measure of cognitive performance relied on self-report in contrast to the report by Kennedy and coworkers.8 Thus, we cannot preclude that cognitive alteration was affected by a general negative self-evaluation that is a leading sign of depression. On the other hand, the questionnaire on cognitive performance is well validated. A further limitation is the comparison of TTP patients with depressive patients only from the literature. The severity of depression of these patients is unknown. Thereby possible confounders could not be considered, for example, chronicity or therapy characteristics. For our observational study on TTP survivors we have no sex- and gender-matched control subjects but rather a general somewhat younger healthy control cohort. However, we used questionnaires that were widely validated in a large cohort and they are applicable without a control group. Second, we did not know why only approximately 60% of the TTP survivors participated in the self-evaluation study. It may be possible that symptomatic patients were more prone to answer the survey compared to asymptomatic patients. Finally, detailed clinical information on severity of TTP bouts was available in only approximately 60% of participating patients. Therefore, prospective assessment of all consecutive patients is initiated.

In conclusion, our observational study illustrates that the prevalence of depression and cognitive deficits was significantly higher in our cohort of 104 individual TTP survivors than in the German population. Despite the high prevalence of depression, only very few (7%) patients were undergoing psychological or psychotherapeutic treatment. We did not detect a significant correlation between severity of depression or cognitive deficits and the frequency or severity of acute TTP episodes. Nevertheless, we demonstrate a highly significant correlation between severity of depression and the degree to which cognitive performance was reduced. Whether or not depression itself directly causes reduced cognitive performance, clinicians should carefully assess depressive and neurocognitive symptoms in TTP survivors and initiate adequate treatment to improve their quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank A. Tadić for his excellent psychiatric support and perfect advising. TF—study concept and design, data analysis, writing of the manuscript, approval; VS—data acquisition and analysis, writing of the manuscript, approval; SH—data acquisition, revision of the manuscript, approval; VW—statistical advice, revision of the manuscript, approval; CvA—data acquisition, approval; SW—advice for study design (selection of the correct questionnaires) and statistical analysis, revision of the manuscript, approval; GH—revision of the manuscript, approval; MB—psychosomatic advice, revision of the manuscript, approval; KL—revision of the manuscript, approval; BL—data compilation, revision of the manuscript, writing of the manuscript, approval; and IS—study supervision, revision of the manuscript, writing of the manuscript, approval.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

IS a member of the Data Safety Monitoring Board in the BAX 930 study (investigating recombinant ADAMTS13 infusion in hereditary TTP). She received travel and accommodation support for participating at scientific congresses or meetings from Bayer and NovoNordisk. BL was chairman of the Data Safety Monitoring Board in the BAX 930 study (investigating recombinant ADAMTS13 infusion in hereditary TTP). He holds a patent on ADAMTS13 and received travel and accommodation support for participating at scientific congresses or meetings from Baxalta, Siemens, Alexion, and Ablynx and speaker's fee from Siemens. GH has received speaker's fee from Servier0020Deutschland GmbH. She reports no conflict of interest with this publication.