An international survey on the role of the hospital transfusion committee

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hospital transfusion committees (HTCs) can oversee all aspects of transfusion practice at a hospital. This survey sought to identify which quality variables were being reported at HTCs around the world.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

A working party composed of members of the Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) collaborative developed a survey of quality variables that could be potentially presented at HTC meetings. The survey was electronically sent to all BEST members who were encouraged to complete it if they were active on an HTC and to send it to other colleagues with similar experience. An expert panel was convened to determine which quality variables are the most important for review at HTC meetings.

RESULTS

There were 121 respondents; the majority were from Europe (52%), Asia (19%), or North America (19%). Most respondents (68%) were at university hospitals. Of the 117 (97%) respondents with an HTC, the committee most often met quarterly (42%) and reviewed transfusion reactions (79%) and risk management–reported events (52%). The HTCs most commonly included transfusion medicine physicians, anesthesiologists, and other physicians who regularly transfuse blood products. Some of the most commonly reported quality variables included number of blood products transfused, wasted, and expired and the number of improperly labeled specimens. The expert panel analysis revealed that some variables that were deemed important were not being frequently reported at HTCs.

CONCLUSION

There is variability in the variables being reported at HTCs around the world with some important variables not frequently reported.

ABBREVIATIONS

-

- BEST collaborative

-

- Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion collaborative

-

- C:T

-

- crossmatch:transfusion ratio

-

- CVI

-

- content validity index

-

- HTC(s)

-

- hospital transfusion committee(s)

-

- PBM

-

- patient blood management

A hospital transfusion committee (HTC) can provide important oversight of transfusion practice and dissemination of transfusion guidelines and monitor the implementation of new programs related to transfusion medicine in the hospital. Often composed of representatives from the various medical and surgical specialties, nurses, and administrators from areas where significant quantities of blood are transfused, its multidisciplinary membership can help identify potential problems related to transfusion or those that are already happening and can help to resolve them. As hospital-based patient blood management (PBM) programs become more widely implemented, the role of the HTC might be expanded to incorporate new reports dealing with the various aspects of this multimodal and multidisciplinary program. In other cases, perhaps an HTC was implemented for the first time to help oversee the development of a nascent PBM program. In all of these cases, the HTC can be the main source of transfusion information and best practices for blood product users at the hospital, as well as effecting change in outdated or problematic policies when necessary.1

In the United States, the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) requires hospitals to implement a quality assessment and improvement plan for overseeing transfusion practice, while some professional and accrediting organizations including the AABB, College of American Pathologists, and the Joint Commission also mandate the quality oversight of this process at the hospital level. In Europe, the “Guide to the Preparation, Use and Quality Assurance of Blood Components,” produced by the Council of Europe, encourages the establishment of an HTC and suggests that it includes representatives of the hospital transfusion service, the blood establishment, and the main clinical units with significant transfusion activity.2 It is recommended that physicians, nurses, and administrative personnel also be represented on the HTC. The Guide also delineates the main goals of the HTC, which include defining blood transfusion policies that are adapted to local clinical activities, and performing regular evaluations of blood transfusion practices. In Italy, specific national laws guide the actions of the HTC, with a specific emphasis on outcome measurements.3 In Spain, the national law requires that all hospitals that transfuse blood components must have an HTC with defined functions that are similar to those of the Council of Europe Guide.4 However, at least in the United States, the regulatory agencies do not typically stipulate the nature of the quality variables that must be reported or in what setting the reporting should occur (reviewed in Shulman and Saxena5). Often the HTC is charged with satisfying these regulatory requirements. Thus, variability in the reported variables, and even in HTC membership, likely exists between different hospitals. To better understand the role of the HTC, its membership, and the quality variables that are currently being reported at HTCs in different contexts around the world, an international survey was performed, along with an expert analysis of which variables are the most important to present at an HTC meeting. The goal was to use the survey data as a menu of quality variables to inform the reporting at newly formed HTCs and to help established HTCs refresh their reported variables in light of the potentially changing scope of transfusion practice that the HTC is overseeing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A working party consisting of members of the Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) collaborative was established to formulate a survey in English regarding the current practices at HTCs around the world, including details on how often the committee meets, its membership, and the nature of the quality variables that are reviewed. An initial version of the survey was piloted among other members of the BEST collaborative for clarity, comprehensibility, and completeness. After editing and revising the survey based on the findings of the pilot study, the survey was encoded into RedCap, an online data management software, and a link to the survey was e-mailed to all members of the BEST collaborative. Members were encouraged to complete the survey if they had firsthand experience as a member of an HTC, and they were asked to forward the survey to other colleagues with similar experience at other institutions.

While the survey responses were being collected, a 10-member expert panel was assembled to rate the importance of the survey variables and, thus, determine which quality indicators are the most important markers to present at HTC meetings. Each member of the expert panel was an academic transfusion medicine specialist and was an active member of their own hospital's transfusion committee. The expert panel was composed of specialists from Europe (n = 5), North America (n = 2), South America (n = 2), and the Middle East (n = 1). Each member of the expert panel was asked to rank the importance of each of the quality variables presented in the survey from 1 (least important to present at an HTC meeting) to 7 (must be presented at an HTC meeting) based on their own opinion of the importance of the variable, regardless of whether or not it was presented at their own hospital's HTC. For each of the variables, the total score from each of the expert panel member's rankings was tabulated and compared to the percentage of survey respondents who indicated that the particular variable was reported at their HTC. As there were 10 experts that participated in this analysis, the maximum score for each variable was 70. The exception was for the question dealing with the ideal frequency at which the HTC should meet; for this variable alone, each member of the expert panel was asked to indicate his or her single preference for the ideal meeting frequency rather than ranking the various options. Thus, the maximum score for this variable was 10. For each graph involving the expert panel's rankings and the responses from the survey, the scales of both axes reflect the maximum score that each variable could obtain (that is, 100% in the survey and either 70 or 10 in the expert panel analysis). Therefore, the heights of the two bars are directly comparable.

In addition, to determine the variables that were consistently ranked as the most important to present at the HTC by the expert panel, a content validity index (CVI) analysis was performed as follows: The number of times that each variable was ranked either 6 or 7 (the two highest scores) by the expert panel was tabulated and then divided by the total number of scores received. If the quotient was at least 0.8 then that variable was consistently ranked as the most important to present at an HTC by the expert panel, and this finding is indicated by gray shading on the bar graph corresponding to that variable.6 Only those variables with a CVI of 0.8 or more are shown on the graphs next to the respondents' percentages. The data from the survey and expert panel were analyzed using computer software (Excel 2010, Microsoft Corp.).

RESULTS

Demographics of respondents' hospitals

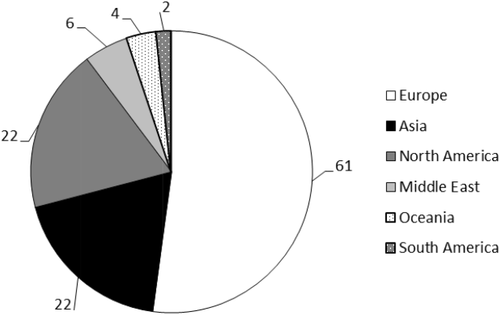

The survey was opened for responses on September 8, 2016, and remained open until November 8, 2016. There were 121 complete responses to the survey collected during that time, and 46 incomplete responses, which were not included in the analysis. Of the 121 complete responses, 117 (97%) respondents reported that their hospital had a transfusion committee. Table 1 demonstrates some demographic characteristics of the 117 hospitals with an HTC that replied to this survey, and Fig. 1 shows the geographic distribution of these hospitals. Of the four hospitals that did not have an HTC, two were from Europe and two were from the Middle East; two were university teaching hospitals while the other two were both community hospitals. The former two hospitals transfused 5001 to 10,000 and 10,001 to 20,000 RBC units/year, respectively, and both had between 501 and 1000 beds; the community hospitals both had between 200 and 500 beds while one transfused 1001 to 5000 RBC units per year and the other transfused 5001 to 10,000 RBC units per year.

Geographic location of the hospitals that reported having an HTC (n = 117).

| Nature of hospital | |

|---|---|

| University/teaching | 79 (67.52) |

| Local/community | 30 (25.64) |

| Pediatric specialty hospital | 3 (2.56) |

| Other specialty hospitalb | 3 (2.56) |

| Reporting for multiple hospitals in a centralized transfusion service | 2 (1.71) |

| Number of beds | |

| >1,000 | 29 (24.79) |

| 501-1,000 | 57 (48.72) |

| 200-500 | 28 (23.93) |

| <200 | 1 (0.85) |

| Reporting for multiple hospitals in a centralized transfusion service | 2 (1.74) |

| Number of RBCs transfused per year | |

| > 20,000 | 31 (26.50) |

| 10,001-20,000 | 32 (27.35) |

| 5,001-10,000 | 26 (22.22) |

| 1,001-5,000 | 25 (21.37) |

| 501-1,000 | 2 (1.71) |

| <500 | 1 (0.85) |

- a Data are reported as number (%).

- b Of the three hospitals that reported being of other specialty, one was a trauma, intensive care unit, and geriatric hospital; one was a trauma and oncology hospital; and one did not specify the nature of its specialty.

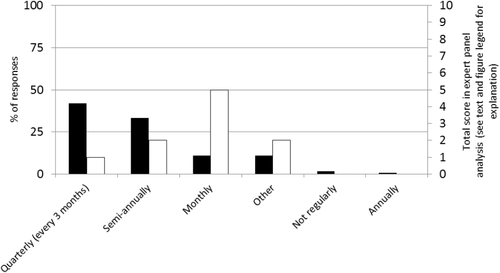

Frequency of HTC meetings

Figure 2 demonstrates how often each HTC meets. The other category included responses such as every 6 weeks (n = 1), eight or nine times per year (n = 2), every 2 months (n = 9), and unspecified (n = 1). Most respondents indicated that their HTC met quarterly, although the most common opinion for the ideal meeting frequency among the expert panel members was monthly.

Frequency of HTC meetings. (◼) Percentage of respondents who answered in the affirmative; (□) total score in the expert panel analysis for each potential frequency. For this variable only, each member of the expert panel was asked to provide his or her opinion as to the single ideal HTC meeting frequency. Therefore, the maximum score in the expert panel analysis for this variable only was 10.

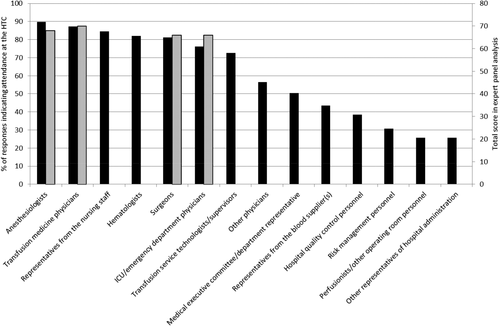

Attendees at HTC meetings

Figure 3 demonstrates the different members of the transfusion committees. There was generally high concordance between the attendees reported by the survey respondents and the expert analysis of the most important attendees, except for highly specialized attendees such as perfusionists and certain hospital department representatives who were reported to not commonly attend the HTC meetings. The expert panel consistently ranked the participation of anesthesiologists, transfusion medicine physicians, surgeons, and emergency department physicians highly, as indicated by the shaded bars.

Attendees at the HTC meetings. (◼) Percentage of respondents who indicated that a particular person attends the HTC meetings. ( ) Variables that were consistently ranked highly in the CVI analysis of the expert scores.

) Variables that were consistently ranked highly in the CVI analysis of the expert scores.

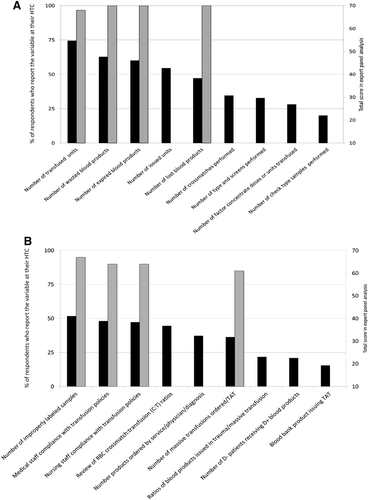

(A) Various transfusion service quality indicators that could be reported at HTCs; (B) some clinical and transfusion service performance metrics that could be reported at HTCs. (◼) Percentage of respondents who responded in the affirmative for each variable. ( ) Variables that were consistently ranked highly in the CVI analysis of the expert scores. TAT = turnaround time.

) Variables that were consistently ranked highly in the CVI analysis of the expert scores. TAT = turnaround time.

Quality indicators and transfusion service performance metrics reported at HTC meetings

Figure 4A demonstrates various transfusion service quality indicators that could be reported at HTCs, while Fig. 4B demonstrates some clinical and transfusion service performance metrics that could be reported at HTCs. According to the expert panel, the indicators of greatest importance included reporting the number of transfused, wasted, expired, and lost blood products, as well as the number of improperly labeled samples, medical and nursing staff compliance with transfusion policies, and the number and turnaround time for massive transfusion protocols.

PBM and/or intraoperative cell salvage reports

Slightly more than half of the respondents (53%) with an HTC indicated that a perioperative blood management report is not presented at their HTC. A significant number of respondents (21%) with an HTC indicated that perioperative blood management activities are not performed at their hospital. Less than 10% of respondents with an HTC indicated that they provide data on how often intraoperative cell salvage machines were utilized, the volume of returned blood, the quality control (QC) of these machines, and a description of any autologous products that are prepared during the surgery-like platelet gel and any accompanying QC information. The expert panel felt that only the number of times that the cell salvage machines were utilized was an important indicator to be reported at the HTC meetings.

Similarly, only a small number of respondents indicated that reports of the number of transfusions that were administered when the patient's laboratory data did not suggest that a transfusion was necessary (23%), intracommittee discussion about whether any outreach to those physicians should occur educating them about the hospital's established transfusion thresholds (17%), and the results of any feedback to or dialogue with the clinicians who administered these transfusions (12%) are given at their HTC meetings. Consistent with the small number of HTCs that review these variables, there was agreement among the expert panel that none of these variables were important for the HTC to review.

Other variables reported at HTC meetings

The participants were also asked if their HTCs reviewed reports of transfusion reactions, risk management incident reports involving transfusion medicine or the hospital's blood bank, and transfusion-related educational activities that had occurred in the hospital since the last meeting. There was agreement among the expert panel that the review of transfusion reactions and risk management incidents were important activities for the HTC. The survey respondents' replies, and the opinion of the expert panel, are presented in Fig. 5.

Percentage of respondents who indicated that their HTCs review reports of transfusion reactions, risk management incidents related to transfusion medicine, and educational activities at their hospital. (◼) Percentage of respondents who responded in the affirmative for each variable. ( ) Variables that were consistently ranked highly in the CVI analysis of the expert scores.

) Variables that were consistently ranked highly in the CVI analysis of the expert scores.

DISCUSSION

The survey revealed that a variety of different quality variables are being presented at HTCs throughout the world. While basic transfusion variables such as the number of products issued, transfused, and wasted are reported at most HTCs, more sophisticated variables that might require complicated calculations or electronic interfaces with the hospital's computerized physician order entry system are less frequently reported. Other more specialized variables, such as a report from the hospital's perioperative blood management program, are also infrequently reported although perhaps as new hospital-based PBM programs are implemented, these reports to the HTC will follow.

In general there was agreement between the respondents' replies in terms of their HTCs' attendees and the expert panel's opinion of the committee's ideal constituents. It was interesting that neither the survey respondents nor the expert panel felt that representatives from the hospital's risk management department, which handles complaints about deviations from hospital policies or reports of dangerous practices, should have greater representation on HTCs than is currently. However, formal risk management departments might not exist at all hospitals, thereby perhaps leaving the resolution of these issues to the HTC itself. Based on the survey replies, it is also likewise possible that departments that are focused solely on quality improvement might not be widely established at hospitals throughout the world, thereby perhaps leaving the responsibility for quality-specific issues to the HTC.

The fact that perfusionists are infrequently members of the HTC is likely a factor of how few hospitals around the world have implemented a perioperative PBM program. Such a program might include using cell salvage equipment to recover shed blood from the operating field,7 preparing autologous products for intraoperative use, or monitoring the use of pharmaceuticals that aid in hemostasis. Almost 75% of the respondents indicated either that a perioperative PBM report is not presented at their HTC (53%) or that perioperative PBM is not performed at their hospital (21%). The experts felt that when cell salvage equipment is utilized, only the number of times that the machines are used should be reported to the HTC.

Less than half of the respondents reported advanced quality variables such as ratios of issued products during trauma and/or massive bleeding (such as RBC unit: plasma unit ratios) and nursing and medical staff compliance with hospital transfusion policies at their HTC meetings. The lack of widespread reporting of the latter two variables, although deemed of high importance by the expert panel, could be due to the difficulty in measuring these variables in the absence of a computerized physician order entry. Similarly, without a manual review on a case-by-case basis, it is difficult to determine how many transfusions were administered without supporting laboratory data, although some American regulators require that a certain percentage of all transfusions must be audited to determine compliance with hospital policy. Calculating the transfusion service's turnaround time on issuing products is also often a manual procedure, which suggests an explanation for the low rate of reporting of this variable. Nevertheless, the experts consistently ranked reporting the issuing turnaround time at the HTC as very important to determine how well the transfusion service is meeting the clinicians' needs. It was interesting that a review of the crossmatch:transfusion (C:T) ratio at the HTC was performed by less than half of the respondents and it did not consistently rank highly in the expert panel. Perhaps this variable is becoming outdated in an era when electronic crossmatching and performing the crossmatch closer to the time of issue is becoming more widespread.8

Interestingly there was a wide range of survey replies with respect to how frequently each HTC meets. While the majority of committees meet every 3 months (42%), others meet less frequently. In fact, some of the experts felt that convening the HTC annually would be sufficient to accomplish its oversight role. This is perhaps because some of the functions of an HTC take place at other hospital-based meetings; perhaps surgical C:T ratios are discussed at surgical services meetings, and perhaps reports of deviations from the hospital transfusion policies are discussed at each medicine and surgical subspecialty meetings. That decentralized reporting of transfusion quality variables might be occurring suggests that a traditional HTC, where all transfusion quality variables are discussed in a single meeting, might be an outdated model. As it relates to quality variables that reflect on clinical services (such as C:T ratios and the administration of potentially inappropriate transfusions), it would be interesting to compare the efficacy of changing the clinicians' practices when the variables are presented at a centralized HTC where not all clinicians attend, to presenting them at subspecialty meetings where face-to-face interactions between the transfusion service's medical leadership and clinicians can occur. The likely higher efficacy of changing practice would need to be balanced against the extra workload for the transfusion service staff that would be necessary to personally attend each of these subspecialty meetings.

The limitations of this study include a high potential for selection bias among the respondents insofar as hospitals that did not have an HTC might not have replied to the survey. Thus, the 97% rate of having an HTC in this survey is unlikely to reflect the true proportion of hospitals that have an HTC around the world. The participants in this survey came mainly from three general geographic parts of the world and so the results reflect the practice in these areas and might not be generalizable to the variables reported at HTCs in other parts of the world. In addition, although the survey was piloted for comprehensibility among a cohort of people, many of whom do not speak English as a first language, it is possible that some respondents did not understand some questions and therefore the answers provided might not have been an accurate reflection of the practice at their hospital. It was not possible to determine how many people in total received the survey link, and hence an overall response rate cannot be calculated. Caution should thus be used if attempting to generalize these results as the potential for a low response rate cannot be excluded. Finally, it should be noted that the expert panel in many cases provided their opinions about the importance of these HTC variables, and so the readers should interpret these opinions in light of their own specific circumstance and situation.

This survey demonstrated the wide variety of practices at HTCs around the world. The inventory of quality variables presented herein, as well as the expert opinion as to the most important variables to report, can help guide newly formed HTCs in selecting the quality variables to present at their meetings, and can also serve as a reference for established HTCs that are overseeing the increasingly complex process of blood transfusion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank our colleagues from around the world who completed the Inventory of Committee Evaluated Hospital Quality Indicators (ICE HoQuI) survey.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.