Improving survey data on pregnancy-related deaths in low-and middle-income countries: a validation study in Senegal

Abstract

enObjective

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), siblings’ survival histories (SSH) are often used to estimate maternal mortality, but SSH data on causes of death at reproductive ages have seldom been validated. We compared the accuracy of two SSH instruments: the standard questionnaire used during the demographic and health surveys (DHS) and the siblings’ survival calendar (SSC), a new questionnaire designed to improve survey reports of deaths among women of reproductive ages.

Methods

We recruited 1189 respondents in a SSH survey in Niakhar, Senegal. Mortality records from a health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS) constituted the reference data set. Respondents were randomly assigned to an interview with the DHS or SSC questionnaires. A total of 164 respondents had a sister who died at reproductive ages over the past 15 years before the survey according to the HDSS.

Results

The DHS questionnaire led to selective omissions of deaths: DHS respondents were significantly more likely to report their sister's death if she had died of pregnancy-related causes than if she had died of other causes (96.4% vs. 70.9%, P < 0.007). Among reported deaths, both questionnaires had high sensitivity (>90%) in recording pregnancy-related deaths. But the DHS questionnaire had significantly lower specificity than the SSC (79.5% vs. 95.0%, P = 0.015). The DHS questionnaire overestimated the proportion of deaths due to pregnancy-related causes, whereas the SSC yielded unbiased estimates of this parameter.

Conclusion

Statistical models informed by SSH data collected using the DHS questionnaire might exaggerate maternal mortality in Senegal and similar settings. A new questionnaire, the SSC, could permit better tracking progress towards the reduction in maternal mortality.

Abstract

frObjectif

Dans les pays à revenus faibles et intermédiaires (PFR-PRI), les histoires de survie de sœurs (HSS) sont souvent utilisées pour estimer la mortalité maternelle, mais les données HSS sur les causes de décès à l’âge de reproduction ont rarement été validées. Nous avons comparé la précision de deux instruments HSS: le questionnaire standard utilisé dans les enquêtes démographiques et de santé (EDS) et le calendrier de survie de sœurs (CSS), un nouveau questionnaire conçu pour améliorer les rapports de surveillance des décès chez les femmes en âge de reproduction.

Méthodes

Nous avons recruté 1189 répondantes, interrogées dans le cadre d'une enquête HSS à Niakhar, au Sénégal. Les registres de mortalité d'un système de surveillance démographique et de santé (SSDS) ont constitué l'ensemble des données de référence. Les répondantes ont été assignées de façon aléatoire à un entretien avec le questionnaire EDS ou le questionnaire CSS. 164 répondantes avaient eu une sœur décédée à l’âge de reproduction au cours des 15 dernières années précédant l'enquête selon le SSDS.

Résultats

Le questionnaire EDS a mené à des omissions sélectives de décès: les répondantes EDS étaient significativement plus susceptibles de déclarer le décès de leur sœur si cette dernière était décédée de causes liées à la grossesse plutôt que suite à d'autres causes (96,4% vs 70,9%; P <0,007). Sur les décès déclarés, les deux questionnaires avaient une sensibilité élevée (>90%) dans l'enregistrement des décès liés à la grossesse. Mais le questionnaire EDS avait une spécificité nettement inférieure à celle du CSS (79,5% vs 95,0%; P = 0,015). Le questionnaire EDS surestimait la proportion de décès dus à des causes liées à la grossesse, tandis que le CSS aboutissait à des estimations non biaisées de ce paramètre.

Conclusion

Les modèles statistiques éclairés par des données HFS recueillies à l'aide de questionnaire EDS pourraient exagérer la mortalité maternelle au Sénégal et dans des cadres similaires. Le CSS permettrait un meilleur suivi des progrès visant la réduction de la mortalité maternelle.

Abstract

esObjetivos

En países con ingresos bajos y medios (PIBMs), las historias de supervivencia de hermanos (HSH) a menudo se utilizan para calcular la mortalidad materna, pero los datos de HSH sobre las causas de muerte en edad reproductiva rara vez han sido validados. Hemos comparado la precisión de dos instrumentos de HSH y el calendario de supervivencia de los hermanos: el cuestionario estándar utilizado durante encuestas demográficas y sanitarias (EDS) y el calendario de supervivencia de los hermanos (SH), un nuevo cuestionario diseñado para mejorar los informes de muerte de mujeres en edad reproductiva.

Métodos

Se reclutaron 1,189 encuestados en un estudio de SH en Niakhar, Senegal. Los datos de mortalidad de un sistema de vigilancia demográfica y sanitaria (SVDS) constituían las bases de datos de referencia. Quienes respondían fueron asignados aleatoriamente a una entrevista con los cuestionarios EDS o SH. 164 de los que respondieron tenían una hermana que había muerto en edad reproductiva en los 15 años previos a la encuesta según el SVDS.

Resultados

El cuestionario EDS llevó a omisiones selectivas de muertes: quienes respondieron al EDS tenían una probabilidad significativamente mayor de reportar la muerte de su hermana si había muerto por causas relacionadas con el embarazo que si había muerto por otras causas (96.4% vs 70.9%, P < 0.007). Entre las muertes reportadas, ambos cuestionarios tenían una gran sensibilidad (>90%) a la hora de registrar las muertes relacionadas con el embarazo. Pero el cuestionario EDS tenía una especificidad significativamente menor que el SH (79.5% vs. 95.0%, P = 0.015). El cuestionario EDS sobreestimaba la proporción de muertes debido a causas relacionadas con el embarazo, mientras que el SH daba cálculos imparciales de este parámetro.

Conclusión

Los modelos estadísticos informados con datos de HSH recogidos utilizando el cuestionario EDS podrían exagerar la mortalidad materna en Senegal y en lugares con características similares. El SH podría permitir un mejor seguimiento de los progresos hacia la reducción de la mortalidad materna.

Introduction

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is a key indicator of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG5), and a proposed indicator of the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It is the number of maternal deaths per 100 000 live births, where maternal deaths refer to ‘the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes’ 1.

In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), vital registration systems are too incomplete to measure MMRs 2, 3. Instead, data on causes of death among women of reproductive ages (e.g. 15–49 years) often come from censuses and siblings’ survival histories (SSH). SSH are collected during surveys like the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) using a standardised questionnaire (‘DHS questionnaire’ thereafter): respondents list their maternal siblings (their ‘sibship’); then they report the age of surviving siblings, as well as the age at death and years since death of deceased siblings. If a respondent's sister died at reproductive ages, interviewers ask whether she died while pregnant, during delivery or within a certain time after a delivery. Some DHS ask the respondent whether their sister died within 42 days of delivery, whereas others use a different interval (e.g. 2 months). If the answer is yes to any of the three questions above, the death is classified as ‘pregnancy-related’ (PR). PR deaths are proxies for maternal deaths even though they include deaths from accidents and incidental causes. They may also include a small number of deaths that occurred outside the risk period defined by ICD-10 if the survey elicited deaths within 2 months of delivery (instead of 42 days).

SSH can yield independent estimates of maternal mortality rates: reported PR deaths constitute the events included in the numerator, whereas the person-years included in the denominator are calculated using information on dates of birth and death of a respondent's sister(s). As PR deaths are rare events however, this ‘sisterhood method’ 4 seldom allows detecting significant MMR declines in LMICs (for an exception, see 5).

(1)

(1)For LMICs with limited vital registration, both UN MMEIG and IHME use GFR estimates described in the World Population Prospects 8. To estimate the mortality envelope, UN MMEIG and IHME combine censuses, surveys and model life tables 9, 10. But to obtain estimates of PMs, they predominantly rely on SSH: IHME used SSH in 38 African countries with limited vital registration 6, whereas SSH represented 81% of the observations pertaining to African countries in the UN MMEIG data set 11.

The validity of MMR estimates produced by UN MMEIG and IHME thus hinges critically on the accuracy of SSH estimates of the PM. But such data have not been thoroughly validated. Evaluations of SSH data quality have focused on investigating whether SSH reproduce known fertility and mortality trends 12-14. Several studies have also compared MMR estimates obtained from SSH using the sisterhood method with MMR estimates from census 15, 13 or longitudinal data (e.g. 16, 17. Discrepancies between MMR estimates could, however, be due to either (i) biases in SSH estimates of the PM, or (ii) other errors that affect the reporting of person-years 18.

Only one study in Matlab (Bangladesh) directly measured bias in SSH estimates of the PM 19, 20. It linked SSH data to prospective mortality records collected for the same sibship by a health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS). HDSS monitors births, deaths and other demographic events prospectively in small populations during regular household visits 21, 22. In Matlab, SSH slightly underestimated the PM compared with HDSS data, because abortion-related PR deaths were misclassified as non-PR. This study has prompted the adoption of adjustment factors in statistical models of the MMR. For example, the UN MMEIG systematically inflates SSH estimates of the PM by 10% prior to including them into its MMR model 11.

We recently conducted another validation study of SSH data in a rural population of Senegal 18. In this study, we have two objectives. First, we assess whether SSH collected using the DHS questionnaire also underestimate the PM in this sub-Saharan setting. Second, we test the hypothesis that a modified SSH questionnaire, the siblings’ survival calendar (SSC), yields more accurate survey data on causes of death among women of reproductive age than the DHS questionnaire.

Data and methods

Reference data set

We used the Niakhar HDSS 23 as reference data set. A baseline census was carried out in 1962 in eight villages of the Niakhar area, followed by another census in 1983, when the study area was expanded to 30 villages. Since then, interviewers use rosters of household residents to monitor pregnancies, births, migrations and deaths during household visits every few months 23. A mother ID number is attributed to each individual. By looking up all individuals with the same mother ID, we can identify the maternal siblings of residents of the Niakhar HDSS. Each recorded death prompts a verbal autopsy (VA): an interviewer asks a relative of the deceased about circumstances of the death, including pregnancy status at the time of death. Physicians review each VA questionnaire and attribute a cause of death using ICD codes 24.

SSH data collection

We tested the DHS questionnaire and a new instrument, the ‘siblings’ survival calendar’ (SSC). We used the SSH questionnaire used during the 2010/11 Senegal DHS, which asked respondents if their sister died within 42 days of delivery. The SSC incorporated probes and recall cues to prevent omissions of siblings during SSH interviews. It also used an event history calendar 25 to improve reports of ages and dates. The primary aim of this validation study was to measure the accuracy of each questionnaire in recording adult deaths (15–59 years old), irrespective of causes of death. The SSC reduced heaping in SSH data and yielded more accurate reports of female deaths at the age of 15–59 years. Further details on the SSH validation study are reported elsewhere 18.

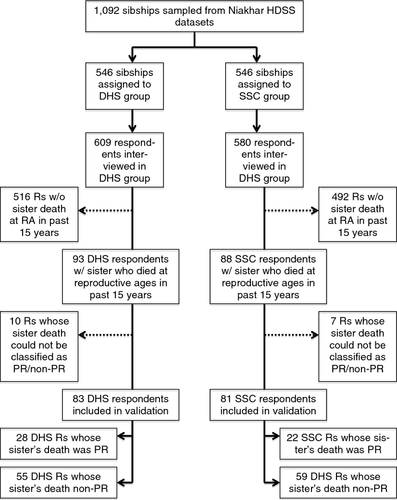

Sampling of respondents

We first selected a stratified sample of (i) sibships in which one sibling (male or female) died between 15 and 59 years old since the beginning of the HDSS (n = 592), and (ii) other sibships, in which no adult deaths were recorded by the HDSS (n = 500). We randomly allocated the sampled sibships to the DHS or SSC groups (Figure 1), and we selected at random up to two surviving members of each sibship. Respondents included both men and women aged 15–59 years old. We recruited eight interviewers who had previously conducted one of the Senegal DHS. Interviewers were unaware of the composition of respondents’ sibships, including whether they were affected by PR or non-PR deaths. In total, 609 respondents from the DHS group were interviewed vs. 580 from the SSC group.

Validation sample

In this paper, we focus on sibships in which a woman died at reproductive ages in the past 15 years according to the HDSS. This timeframe matches the inclusion criterion used in the Matlab validation study 19 and the reference period used in IHME models 6. Some respondents belonged to a sibship in which no death at reproductive ages was recorded by the HDSS in the past 15 years. SSH data on causes of death reported by these respondents cannot be validated because HDSS data on their sibships may be incomplete. For example, if the sister of a respondent moved out of the HDSS area and later died, her death would not be captured by HDSS 23, but would potentially be reported during SSH. In total, 516 respondents from the DHS group and 492 respondents from the SSC group were excluded for this reason (Figure 1). We describe the reporting of deaths at reproductive ages among that sub-sample separately (Appendix S1).

Reference measures of causes of death

To classify deaths as PR vs. non-PR, we did not use the ICD codes assigned by physicians. We used HDSS records to calculate the difference (in days) between the date of death of a respondent's sister and the date of her last delivery. Deaths that had occurred within 42 days of a delivery were classified as PR. If the death had not occurred within 42 days of a delivery, we reviewed VA questionnaires to determine whether the deceased was pregnant when she died. If so, the death was also classified as PR. Some deaths could not be classified as PR or non-PR according to the HDSS because of missing VA data. The HDSS recorded more than one female death at reproductive ages in only one sibship: both deaths in that sibship were non-PR.

Reporting errors in SSH

Two types of reporting errors may bias SSH estimates of the PM 26. Selective omissions happen when the likelihood of reporting a sister's death depends on her cause of death. For example, if respondents do not list 20% of their sisters whose death was PR during SSH vs. 10% of their sisters whose death was not PR, the PM will be underestimated. Misclassifications occur when respondents correctly report that their sister died at reproductive ages, but misstate the circumstances of her death. For example, they may state that she was not pregnant at the time of her death, when in fact she was. All else being equal, the PM will be underestimated if PR deaths are reported as non-PR, but overestimated if non-PR deaths are reported as PR.

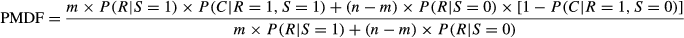

Analytical framework

(2)

(2)Data analysis

First, we measured the number of PR and non-PR deaths recorded by the HDSS in the past 15 years and described differences in characteristics of PR vs. non-PR deaths. These characteristics included the total number of maternal siblings in the sibship of the deceased, her age at death according to the HDSS and the time since her death. Second, we tested for differences in sibship and respondent characteristics between the DHS vs. SSC groups. Respondent characteristics included age, gender, education, religion and language(s) spoken. Third, for each questionnaire, we calculated (i) the probability of reporting a death at reproductive ages during SSH by cause of death (PR vs. non-PR), (ii) the sensitivity of SSH and (iii) the specificity of SSH. We used χ2 tests to test the null hypothesis that there were no selective omissions of deaths in SSH and to test for differences in sensitivity and specificity between questionnaires. To account for possible differences between DHS and SSC groups, we used logistic regressions with controls for sibship and respondent characteristics listed above. Standard errors were adjusted for clustering of respondents within sibships.

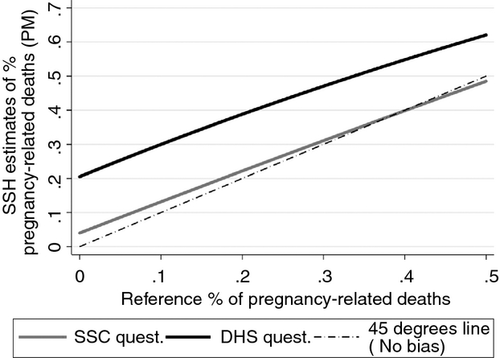

Finally, we used estimated parameters (i.e. prevalence of selective omissions, sensitivity and specificity) in conjunction with Equation 2 to predict PM estimates according to each SSH questionnaire. We considered a series of 50 hypothetical populations in which there were 100 deaths (i.e. n = 100) and in which m (i.e. the number of PR deaths) varied between 0 and 50. The true PM thus ranged from 0 to 0.5 in these populations. We substituted m and n, as well as the observed values of P(R¦S = 0), P(R¦S = 1), P(C¦R = 1, S = 0), P(C¦R = 1, S = 1) according to each questionnaire, into Equation 2. For each value of m, we compared (i) the predicted value of the SSH estimate of the PM and (ii) the true PM, that is m/n.

Results

Descriptive statistics

According to HDSS, there were 136 deaths among women of reproductive ages in the 15 years before the SSH survey. Thirteen deaths (potentially reported by 17 respondents, Figure 1) could not be classified as either PR or non-PR on the basis of HDSS data. In total, there were 38 PR deaths and 85 non-PR deaths potentially reported by 164 respondents. Most deaths occurred among women aged 15–24 years old (Table 1). Half of all PR deaths occurred at the time of delivery vs. 21% during pregnancy and 29% within 42 days of delivery.

| Deceased characteristics | Pregnancy-related deaths (N = 38) | Deaths not related to pregnancy (N = 85) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family size | |||

| 1–4 maternal siblings | 6 (15.8) | 22 (25.9) | 0.428 |

| 5–9 maternal siblings | 27 (71.0) | 51 (60.0) | |

| 10+ maternal siblings | 5 (13.2) | 12 (14.1) | |

| Time since death | |||

| 0–4 years | 10 (26.3) | 25 (29.4) | 0.910 |

| 5–9 years | 16 (42.1) | 36 (42.4) | |

| 10+ years | 12 (31.6) | 24 (28.2) | |

| Age at death | |||

| 15–24 years | 20 (52.6) | 40 (47.1) | 0.353 |

| 25–34 years | 11 (29.0) | 19 (22.4) | |

| 35+ years | 7 (18.4) | 26 (30.6) | |

| Timing of death | |||

| During pregnancy | 8 (21.0) | – | – |

| At delivery | 19 (50.0) | – | |

| Within 42 days of delivery | 11 (29.0) | – | |

- P-values were obtained using chi-square tests of the association between two categorical variables. Numbers in parentheses are column percentages. 13 deaths could not be classified as PR or non-PR and are not included in this table and in the subsequent analyses.

We interviewed 50 respondents who were siblings of women whose death was PR: 22 were assigned to the SSC and 28 to the DHS questionnaire (Figure 1). We interviewed 114 respondents who were siblings of women whose death was non-PR: 59 were assigned to the SSC and 55 to the DHS questionnaire. Respondents in the SSC group were significantly older than in the DHS group (P = 0.015, Table 2). The median age of respondents in the SSC group was 31 years old, vs. 27 in the DHS group.

| DHS questionnaire | SSC questionnaire | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean/proportion | N | Mean/proportion | ||

| Sibship characteristics | |||||

| Family size | |||||

| 1–4 maternal siblings | 13 | 15.7 | 14 | 17.3 | 0.347 |

| 5–9 maternal siblings | 54 | 65.1 | 58 | 71.6 | |

| 10+ maternal siblings | 16 | 19.3 | 9 | 11.1 | |

| Time since death of sister at reproductive ages | |||||

| 0–4 years | 25 | 30.1 | 24 | 29.6 | 0.899 |

| 5–9 years | 37 | 44.6 | 34 | 42.0 | |

| 10+ years | 21 | 25.3 | 23 | 28.4 | |

| Age of sister at death | |||||

| 15–24 years | 41 | 49.4 | 43 | 53.0 | 0.729 |

| 25–34 years | 18 | 21.7 | 19 | 23.5 | |

| 35+ years | 24 | 28.9 | 19 | 23.5 | |

| Respondent characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 15–24 years | 32 | 38.6 | 17 | 21.0 | 0.015 |

| 25–34 years | 32 | 38.6 | 29 | 35.8 | |

| 35–44 years | 8 | 9.6 | 20 | 24.7 | |

| 45+ years | 11 | 13.2 | 15 | 18.5 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 36 | 43.4 | 44 | 54.3 | 0.161 |

| Female | 47 | 56.6 | 37 | 45.7 | |

| Place of interview | |||||

| Niakhar HDSS area | 50 | 60.2 | 49 | 60.5 | 0.972 |

| Outside of Niakhar HDSS area | 33 | 39.8 | 32 | 39.5 | |

| Education | |||||

| No schooling | 49 | 59.8 | 43 | 53.1 | 0.423 |

| Primary schooling | 16 | 19.5 | 23 | 28.4 | |

| Secondary schooling & higher | 17 | 20.7 | 15 | 18.5 | |

| Religion | |||||

| Muslim | 69 | 83.1 | 61 | 75.3 | 0.221 |

| Christian | 14 | 16.9 | 20 | 24.7 | |

| Other | – | – | – | – | |

| Languages spoken | |||||

| Sereer | 81 | 97.6 | 81 | 100.0 | 0.504 |

| Wolof | 76 | 91.6 | 79 | 97.5 | 0.176 |

- P-values are based on a χ2 test of the difference between both arms of the RCT for categorical variables.

Validation results

The DHS questionnaire was affected by selective omissions of deaths (Table 3). Among DHS respondents whose sister died of PR causes according to HDSS, 27/28 reported a death at reproductive ages (96.4%, Table 3). This was significantly lower (39/55, 70.9%) among DHS respondents whose sister died of non-PR causes (P = 0.007). Among SSC respondents, we could not detect selective omissions of deaths (P = 0.469).

| Sibships with non pregnancy-related deaths | Sibships with one pregnancy-related death | P-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported/expected | % (95% CI) | Reported/expected | % (95% CI) | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| DHS questionnaire | 39/55 | 70.9 (56.6, 82.0) | 27/28 | 96.4 (78.9, 99.5) | 0.007 | 11.1 (1.41, 87.0) | 11.6 (1.59, 84.4) | 10.7 (1.28, 88.9) |

| SSC questionnaire | 50/59 | 84.8 (70.6, 92.8) | 20/22 | 90.9 (71.4, 97.6) | 0.469 | 1.8 (0.36, 9.02) | 2.2 (0.45, 10.6) | 1.4 (0.27, 7.39) |

- ‘Reported’ refers to the number of respondents who reported a death at reproductive ages (15–49) among their sisters over the past 15 years; ‘Expected’ refers to the number of respondents who were members of sibships in which there was at least one PR/non-PR death in the past 15 years; P-values test the null hypothesis of no difference in proportion of respondents reporting a death at reproductive ages over the past 15 years between sibships with a PR death and sibships with only non-PR deaths. This P-value is based on a χ2 test. Standard errors are adjusted for the clustering of respondents within sibships. OR = odds ratio; ORs are obtained from logistic regressions in which the dependent variable is a dummy variable taking value 1 if the survey respondent reported a death at reproductive ages (irrespective of cause), and 0 if no such death was reported. The key dependent variable is a dummy variable taking value 1 if the respondent was member of a sibship in which one death was PR, and 0 if the respondent was member of a sibship where the death was non-PR. OR > 1 thus indicates that respondents were more likely to report a death at reproductive ages (irrespective of cause) if their sister had died of PR causes. Model 1 includes additional control for covariates associated with assignment to the DHS vs. SSC questionnaire in bivariate analyses at the P = 0.2 level (see Table 2). Model 2 includes controls for all variables listed in Table 2. Among the 10 respondents in the DHS group for which HDSS data did not permit assessing the sister's cause of death, two reported a PR death. Among the seven respondents from the SSC group in a similar case, one reported a PR death.

The DHS and SSC questionnaires had similar sensitivity (92.6% vs. 90.0%, P = 0.744), but the SSC had significantly higher specificity than the DHS questionnaire (Table 4). In sibships with non-PR deaths according to HDSS, 48/50 SSC respondents correctly classified the reported death as non-PR (95.4%) vs. 31/39 DHS respondents (79.5%, P = 0.014).

| DHS questionnaire | SSC questionnaire | P-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct/reported | % (95% CI) | Correct/reported | % (95% CI) | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Sensitivity | 25/27 | 92.6 (74.6, 98.2) | 18/20 | 90.0 (69.5, 97.3) | 0.744 | 1.39 (0.19, 10.2) | 0.97 (0.14, 6.63) | –* |

| Specificity | 31/39 | 79.5 (64.1, 89.4) | 48/50 | 96.0 (85.5, 99.0) | 0.014 | 6.19 (1.22, 31.4) | 5.92 (1.12, 31.3) | 6.60 (1.22, 35.7) |

- Sensitivity refers to the proportion of deaths classified as pregnancy-related using the HDSS data, which were also reported as pregnancy-related during the SSH survey. Specificity refers to the proportion of deaths classified as not pregnancy-related using the HDSS data, which were also reported as not pregnancy-related during the SSH survey. P-values measure differences in sensitivity between the SSC and DHS questionnaires. They were based on a χ2 test of association. Standard errors were adjusted for the clustering of respondents within sibships. OR = odds ratio; ORs are obtained from logistic regressions in which the dependent variable is a dummy variable taking value 1 if the survey reported a cause of death (PR vs. non-PR) that was concordant with the cause of death ascertained by the HDSS. The key dependent variable is a dummy variable taking value 1 if the respondent was assigned to an interview with the SSC questionnaire, and 0 if s/he was assigned to the DHS group. In that case, an OR > 1 thus indicates that respondents assigned to the SSC group were more likely to report a concordant cause of death than respondents assigned to the DHS group. Model 1 includes additional control for covariates associated with assignment to the DHS vs. SSC questionnaire in bivariate analyses at the P = 0.2 level (see Table 2). Model 2 includes controls for all variables listed in Table 2. *There were too few cases to estimate this model.

The DHS questionnaire consistently overestimated the PM (Figure 2). For example, in a population where the true PM is 10%, the estimated PM obtained from the DHS questionnaire was approximately 30%. The SSC yielded PM estimates that were, at most, four percentage points higher than the true PM.

Discussion

In LMICs with limited vital registration, maternal mortality is often estimated from survey data. It is thus crucial to validate and improve SSH, that is the instrument used to record causes of death among women of reproductive ages during surveys. We compared SSH collected using two different questionnaires to high-quality prospective mortality data from a HDSS in Senegal. The DHS questionnaire was prone to selective omissions of deaths, with PR deaths more frequently reported. Among reported deaths, the DHS questionnaire had high sensitivity, but low specificity: respondents misclassified non-PR deaths as PR. These reporting errors lead to large overestimates of the PM.

These findings contrast with another validation study in Matlab (Bangladesh), where the DHS questionnaire underestimated the PM 20. In Matlab, there were no selective omissions of deaths, but SSH respondents misclassified abortion-related deaths as non-PR, either because they were not aware of their sister's pregnancy or because of social desirability bias associated with abortions. The DHS questionnaire likely had higher sensitivity in Niakhar, because abortion-related deaths are less common in rural Senegal: most PR deaths occur during or after delivery 24, 27.

The DHS questionnaire was less accurate in recording non-PR deaths in Niakhar. This may be because SSH respondents under-report non-PR deaths due to stigmatised causes of death. In Niakhar, epilepsy – an often-stigmatised condition in sub-Saharan countries 28 – was the most frequent cause of death attributed by physicians among omitted non-PR deaths (5/16, 31.3%). SSH respondents may also inaccurately assess the timing of their sister's death, that is whether it took place within 42 days of delivery.

This study also constitutes a unique attempt to improve the accuracy of SSH data on PR mortality. Compared with the DHS questionnaire, a new SSH questionnaire, the siblings’ survival calendar (SSC), was not affected by selective omission of deaths and had significantly higher specificity. Probing and recall cues incorporated in the SSC likely helped respondents report of a number of non-PR deaths, which were omitted during DHS interviews. The event history calendar likely helped respondents determine the timing of their sisters’ deaths. The SSC yielded virtually unbiased estimates of the PM.

There are several limitations. First, the HDSS does not constitute a gold standard on PR mortality 29. However, our findings remained after accounting for the possibility of misclassifications in the HDSS data set (Appendix S2). Second, our analyses are limited by small sample size, particularly our tests of the difference in sensitivity between questionnaires. We also could not test whether the effects of the SSC varied by sibship or respondent characteristics. Third, our study included men and individuals aged 50–59 years old as respondents. These two groups are not always included in SSH data collection during DHS. There are, however, calls to more systematically include men and older respondents in SSH data collection during DHS and other surveys 30, 31. Fourth, we did not consider the impact of reporting errors on confidence intervals calculated for MMR estimates. The width of confidence intervals of MMR estimates depends on a number of parameters including sample size, cluster survey structure and uncertainty associated with model specification 6, 11. A full assessment of the impact of reporting errors on confidence intervals thus requires more complex analytical frameworks and simulations. Fifth, a respondent may sometimes report that her sister is alive, when in fact she died before the survey. Such vital status errors may affect PM estimates, but they are very rare: in a previous study in Senegal, we found that the DHS questionnaire had 100% specificity and 99.6% sensitivity in recording the vital status of adult siblings 18. Sixth, we tested a version of the DHS questionnaire, which elicited PR deaths having occurred within 42 days of the delivery. Some DHS, however, use 2 months instead to elicit post-partum PR deaths. According to the Niakhar HDSS, there were no deaths that took place between 42 and 60 days after a delivery. The results of this validation are thus likely not affected by different choices of a risk period for PR deaths. Finally, the generalisability of our findings may be limited because (i) HDSS only provided reference data for a subset of the Niakhar population, (ii) inhabitants of the Niakhar area may be more aware of causes of deaths than respondents in other settings due to long-term demographic surveillance, and (iii) the Niakhar HDSS population has significantly lower schooling than the rest of Senegal 23.

Our results nonetheless have important implications. First, they suggest that the statistical models currently used to track progress towards MDG5 should be re-examined. Some of these models adjust SSH data for forgetting of adult deaths, but do not attempt to correct misreporting of causes of deaths in SSH data 6, 31. Other models assume that SSH universally underestimate PR mortality and apply a single correction factor to all SSH data sets 11. All things being equal, these analytical strategies may lead to overestimates of the level of maternal mortality in Senegal and similar settings. Second, our results suggest that the accuracy of SSH can be improved by adopting a new questionnaire, the SSC. Further research is needed to validate data collected by the SSC in additional epidemiological settings (e.g. populations with high HIV prevalence), and to address possible barriers to the integration of the SSC into large-scale surveys. Such barriers include additional training and interviewing time. Refining training protocols and/or transferring the SSC to mobile data collection can address these barriers. Ultimately, the SSC may permit better tracking progress towards the reduction in maternal mortality.