The Role of Minimum Income Schemes in Poverty Alleviation in the European Union

ABSTRACT

Assessing the effectiveness of Minimum Income (MI) schemes in poverty alleviation is challenging. Studies based on survey microdata are usually subject to bias because households tend to underreport benefit receipts. Studies based on microsimulation models tend to overestimate these benefits mainly due to high non-take-up rates. In this paper, we tackle these challenges by calibrating the simulation of MI schemes in the microsimulation model EUROMOD to match official expenditure results for each European Union (EU) Member State's scheme. We use this calibrated model to evaluate the poverty-alleviating effects of existing MI schemes and explore the impacts of possible reforms toward eradicating extreme poverty. Our results show that MI support varies widely across EU countries, with most failing to reach half of households in extreme poverty or provide adequate support, particularly for larger families. Reforms aimed at improving coverage and adequacy could eradicate extreme poverty at a relatively low budgetary cost.

1 Introduction

Minimum Income (MI) schemes play a crucial role in alleviating poverty and social exclusion in the European Union (EU), constituting a last-resort safety net for households with insufficient resources. While all EU countries provide some form of MI support (see Natili 2020 for a typology of MI schemes in the EU), the effectiveness of these schemes in reaching those in need is highly heterogeneous across countries (Coady et al. 2021; Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland 2013; Frazer and Marlier 2016; Immervoll et al. 2022; Nelson 2013). This heterogeneity typically reflects the interaction between two main dimensions: (i) coverage, that is, the extent by which support reaches individuals in need, and (ii) adequacy, that is, the generosity of the support provided. Recently, the European Commission has proposed a Council Recommendation to improve, among other features, these two dimensions of MI support (European Commission 2022a).

Comparing the effectiveness of MI schemes across countries poses several methodological and data-related challenges. Some studies perform a somewhat descriptive analysis based on institutional country-level data reporting benefit levels for hypothetical family types (Marchal, Marx, and Mechelen 2014; Nelson 2010; Wang and Van Vliet 2016). While this approach provides simple and comparable results on the heterogeneity of MI provisions across countries, it does not allow for an assessment of their distributional effects, given the non-granularity of the data. Other studies, while also adopting a descriptive approach, take a step further, using self-reported survey microdata (Ayala and Bárcena-Martín 2020; Coady et al. 2021; Immervoll et al. 2022) or administrative microdata (Bargain, Immervoll, and Viitamäki 2012). Administrative microdata, although more comprehensive and precise in nature, are often not easily accessible, and lack cross-country comparability. In contrast, survey data are more easily available and typically subject to harmonization procedures. Yet, they usually suffer from bias as households with low incomes tend to under-report benefit receipts (Bargain, Immervoll, and Viitamäki 2012; Figari et al. 2012; Lynn et al. 2004), which leads to an underestimation of the support provided by MI schemes.

An alternative approach is to use microsimulation modeling (Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland 2013), which simulates the levels of MI benefits for each entitled unit according to the policy rules in place in each country. This method proves to be useful in addressing the problem of under-reporting of benefit receipt present in survey data (Figari et al. 2012), as it allows for a more accurate identification of the population eligible to receive MI support. Furthermore, it provides a finer assessment of the different existing MI schemes, clearly disentangling them from other similar cash benefits that tend to be aggregated in surveys.1 However, microsimulation modeling also faces limitations, mostly related to the lack of detailed data necessary to accurately simulate some eligibility conditions, as well as the large extent of non-take-up of these benefits (Ko and Moffitt 2024). This leads to an overestimation of cash benefits (Figari et al. 2012; Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland 2013; Jara and Tumino 2013; Sutherland and Figari 2013), particularly MI schemes, reflecting their “intended” effects rather than their actual impact.

In this paper, we explore a new approach to the comparison of MI schemes across countries, which builds on the advantages of microsimulation models while trying to overcome the limitations of this approach, using the methodology developed by Hernández, Picos, and Riscado (2022). We use EUROMOD, a static tax-benefit microsimulation model for all EU countries, and apply a calibration procedure that corrects for the overestimation of MI schemes by matching the simulated levels of expenditure to official recorded expenditure data from administrative sources. Although ad-hoc corrections to the simulation of MI schemes have been explored from a country-specific perspective (e.g., Tasseva 2016) or for a selection of EU countries (e.g., Matsaganis, Paulus, and Sutherland 2008), this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first time that such assessment has been conducted for all EU countries using a harmonized approach. Having obtained a new “closer to reality” baseline, we then provide new estimates of the effectiveness of existing MI schemes, focusing on their levels of coverage and adequacy and their poverty-alleviation effects. Furthermore, we explore possible reforms to existing schemes, simulating a number of stepwise scenarios with the aim of eradicating extreme poverty in the EU and estimating the corresponding “morning-after” cost.

Our paper contributes to the literature on the evaluation of MI schemes in four main ways. First, it provides a new methodological framework, which departs from previous microsimulation studies focused on the “intended” effects of MI schemes (e.g., Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland 2013) by introducing a calibration procedure to correct for the overestimation of benefit recipiency. The new methodology not only produces a “closer to reality” simulation of existing MI support in each EU country, but also constitutes a harmonized framework that can be used for comparisons in a consistent way. This is key for public policy purposes, as it increases the accuracy and comparability of MI support and poverty measurement across EU Member States. Second, the paper introduces an innovative framework for identifying existing gaps and reflecting on possible ways to reform current MI schemes, sharing useful insights about the potential and challenges of different options, which is also a crucial input from a policy perspective. Third, the paper presents updated results for all EU countries (the last cross-country estimates were produced more than 10 years ago for 14 EU countries, in Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland 2013). Having up-to-date estimates is crucial for EU policymakers, to identify existing gaps and understand in which dimensions there is still room for improvement. Finally, the paper delivers estimates of coverage and adequacy using both stricter and broader definitions of MI protection. By doing so, we shed new light on the sensitivity of results to the definition of MI schemes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the concept and main characteristics of MI schemes in the EU. In Section 3, we present the way these schemes are simulated in EUROMOD and discuss some limitations. In Section 4, we introduce our calibration procedure and provide some indicators to validate the new calibrated baseline simulation. In Section 5, we assess the effectiveness of existing EU MI schemes in poverty alleviation based on the new calibrated baseline simulation. In Section 6, we describe the hypothetical reform scenarios and present the impact that they would have on the anti-poverty effectiveness and cost of MI schemes in the EU. Finally, Section 7 discusses the main results, limitations of our approach, and avenues for future research.

2 Concept and Main Characteristics of MI Schemes in the European Union

As described by European Commission (2022a), the provision of MI protection encompasses a large variety of instruments, namely benefits in cash or in-kind, social services, and tailored assistance. Finding an appropriate and comparable definition for a MI scheme is a challenging task. In its broader definition, this would be a cash benefit that helps guaranteeing a MI floor, implying that several schemes would fit such objective. As pointed out by Casas (2005), “there is a wide degree of divergence around the understandings and definitions of this MI floor in the EU.” The author illustrates this by presenting how the different country-specific schemes refer in some cases to the concept of “minimum” (e.g., “minimum living income” in Spain or “guaranteed minimum income” in Greece), whereas in others, these are labeled without any explicit allusion to this concept (e.g., “subsistence benefit” in Estonia or “benefit in material need” in Slovakia). These heterogeneous understandings are also reflected in the literature, with different studies considering wider or stricter classifications of MI schemes. For example, in Spain, Ayala et al. (2021) broadly review all means-tested non-contributory benefits in their analysis of the effectiveness of MI protection, including, for example, unemployment assistance. For the same country, however, Hernández, Picos, and Riscado (2022) consider unemployment assistance an intermediary step before MI support.

While harmonization remains a challenge, and acknowledging that a conceptual discussion goes beyond the scope of this paper, our definition of MI schemes relies on similar grounds as the one in Natili (2020). This broadly means considering MI schemes as anti-poverty cash benefits, with means-tested and non-contributory characteristics, which usually work as a top-up depending on family size and composition. This implies that MI schemes complement all other incomes, including other benefits, up to the MI threshold. These attributes lead us to consider only the “core” MI schemes of each EU country—“core” in the sense of meeting most of these characteristics, and not “core” quantitatively-wise (e.g., expenditure vis-à-vis other benefits).2 Furthermore, we focus on schemes targeted at the working-age population, excluding schemes directed only at the elderly and schemes covering special circumstances, such as disability. We typically exclude unemployment assistance schemes as well.3 Following these criteria, we identify the schemes presented in Table 1 as the MI schemes to be considered in the analysis.4 We focus on the schemes in place in 2019, a choice we discuss in the next section.5 When cross-checking this list with the schemes included in the European Commission's 2019 Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC) for the working-age population, we find that they largely coincide.6

| Key features | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | MI scheme | Residence requisite | Age requisite | Owner-occupied housing condition | Earnings disregard |

| AT | Guaranteed minimum resources (Mindestsicherung) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| BE | Integration income (Revenu d'intégration/leefloon) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| BG | Social assistance allowances (Mесечни социални помощи) | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| CY | Guaranteed Minimum Income (Eλάχιστo Eγγυημένo Eισόδημα) | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| CZ | Allowance for Living (Příspěvek na živobytí) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| DEa | Subsistence benefit (Hilfe zum Lebensunterhalt) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Unemployment assistance for jobseekers (Grundsicherung für Arbeitsuchende) | Yes | ||||

| DK | Social assistance (Kontanthjælp) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| EE | Subsistence benefit (Toimetulekutoetus) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| EL | Social Solidarity Income (KΟINΩNIKΟ EI∑ΟΔHMΑ ΑΛΛHΛEΓΓYH∑) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ESa,b | Regional Minimum Income Schemes (Rentas Mínimas de Inserción) | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Minimum Living Income (Ingreso Minimo Vital) | |||||

| FI | Basic Social Assistance (Perustoimeentulotuki) | No | No | No | Yes |

| FRa | Active solidarity income (Revenu de Solidarité Active, RSA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Employment bonus (Prime d'activité) | |||||

| HR | Guaranteed minimum benefit (Zajamčena minimalna naknada) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| HU | Benefit for persons in active age (Aktív Korúak Ellátása) | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| IEa | Supplementary Welfare Allowance | No | No | No | No |

| Jobseeker's Allowance | Yes | ||||

| IT | Guaranteed Minimum Income or Pension (Reddito di Cittadinanza) | Yes | No | No | No |

| LT | Cash social assistance (Piniginė Socialinė Parama) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| LU | Social inclusion income (Revenu d'inclusion Sociale, Revis) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| LV | Guaranteed minimum income benefit (Pabalsts garantētā minimālā ienākuma līmeņa nodrošināšanai) | No | No | No | No |

| MTa | Social assistance (Ghajnuna Socjali) | No | Yes | No | No |

| Unemployment Assistance (Gℏajnuna gℏal-Diżimpjieg) | |||||

| NL | Participation Act (Participatiewet) | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| PL | Periodic Allowance (Zasiłek okresowy) | No | Yes | No | No |

| PT | Social integration minimum income (Rendimento social de inserção) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| RO | Social Aid (Ajutor social) | No | Yes | No | No |

| SE | Social assistance (Ekonomiskt bistånd) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| SI | Financial Social Assistance (Denarna Socialna Pomoč) | No | No | No | No |

| SK | Material Need Benefit (Dávka v hmotnej núdzi) | No | Yes | No | Yes |

- Source: Our own elaboration based on EUROMOD Country Reports, MISSOC database, and European Commission (2022a, 2022b).

- a When examining countries with two MI schemes, we have attempted, wherever possible, to distinguish the key features of each scheme. In cases where detailed information on both schemes was unavailable, we assumed that the conditions of the primary scheme also applied to the secondary one.

- b In Spain, regional MI schemes are highly diverse across regions. For example, some regions apply earnings disregards, while others do not. For a more comprehensive analysis, see Hernández, Picos, and Riscado (2022).

We acknowledge that our focus could eventually result in analyzing some schemes that are either residual, due to the delivery of previous major insurance-related benefits, or more ambitious because the welfare regimes of certain countries are not predominantly structured around insurance-related programs (see Immervoll et al. 2022 pages 8 and 9 for a detailed discussion). Moreover, by focusing on the “core” MI schemes, we are de facto analyzing only anti-poverty instruments. As such, we generally leave aside complementary sources of support not explicitly targeted at poverty reduction, to which the claimant has to apply separately, such as housing benefits and family allowances, among others. This may imply excluding some benefits that, in practice, have a non-negligible impact on poverty alleviation. For example, although child-related benefits primarily aim at compensating childrearing costs, they can be more effective at reducing child poverty than strict anti-poverty schemes (Bárcena-Martín, Blanco-Arana, and Pérez-Moreno 2018; Leventi, Sutherland, and Tasseva 2019). Consequently, our analysis should not be interpreted as a comprehensive study of the effectiveness of all forms of MI protection in poverty alleviation, but rather as a “scheme-based” analysis. However, we believe our approach has at least two advantages with respect to a more encompassing conceptualization of MI protection. First, it allows for a clear identification of the policy instrument under assessment, which favors more concrete scheme-oriented recommendations for potential reforms. Second, it focuses on evaluating the main goal of these policies, that is, poverty alleviation. If the schemes under assessment do not address to a reasonable extent this goal, even if other schemes do indirectly, policymakers may consider redesigning the benefits system to ensure that MI benefits can be clearly identified as the key anti-poverty tool.

Besides the above-discussed conceptual definitions, MI schemes are characterized by a set of rules. These rules determine the eligibility to access the benefit, the extent to which the benefit can be combined with employment income, whether the benefit is taxable, among others. They can be broadly classified into two categories: non-income related rules and income related rules. Non-income related rules typically pertain to socio-demographic characteristics, asset ownership, and job-search related requirements. Income related rules usually refer to disregards in employment income when computing the amount of the MI benefit, the existence of complementary benefits, and the rules of taxation applied to the MI benefit. In Table 1 we identify whether four of these rules are present in each country, which are the ones that show higher heterogeneity across countries. In Table A4 of Appendix 1 we provide a more comprehensive and detailed list of the most relevant rules.

In most countries, several non-income related rules apply, with countries varying significantly in the degree of restrictions that they impose. For example, while in Italy a minimum of 10 years of residence is needed to qualify for the MI benefit, in Latvia no minimum period is required. Similarly, while in Cyprus only adults aged 28 years or older can qualify, in Austria there are no age requirements. While restrictions on time of residence and age are applied in only a part of EU countries, the vast majority has some type of constraint on asset ownership and job-search efforts. Income-related rules are also present in most countries, with the extent of requirements varying across countries. Typically, a share of employment income is disregarded when computing the amount of the MI benefit, although not in all countries, and one or more complementary allowances may be provided, including housing allowances. In most countries, MI benefits are not subject to income tax.

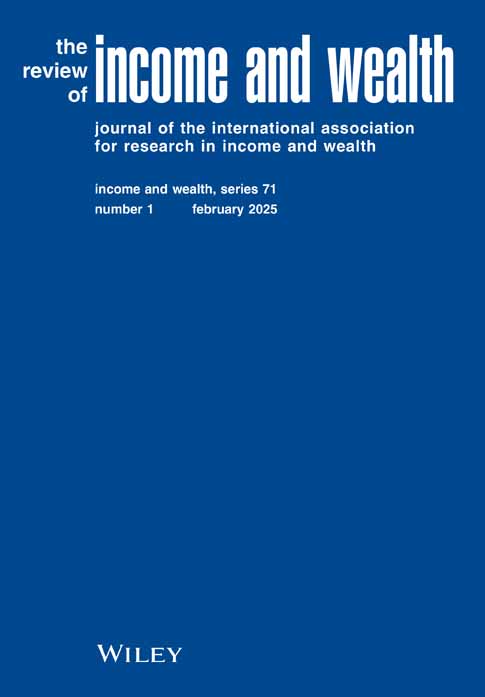

The spending with MI schemes varies considerably across EU countries (Figure 1). The cost of MI schemes as a percentage of GDP ranges from 0.02% in Latvia to 0.78% in France. The six countries depicting the highest expenditure are France, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Germany, and Denmark, where MI support represents at least 0.5% of the GDP of each country. On the contrary, in Romania, Czechia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, and Latvia, the expenditure in MI schemes accounts for only up to 0.06% of the GDP. The differences in spending are likely to reflect several factors, including the strictness of the eligibility criteria, take-up rates, and the rules applied when calculating the amount of MI benefit for each beneficiary.

Source: Data on MI official recorded expenditure obtained from EUROMOD Country Reports. GDP data retrieved from Eurostat

.3 The Simulation of MI Schemes in EUROMOD

The analysis in this paper uses EUROMOD, the open-source static non-behavioral tax-benefit microsimulation model for all EU countries.7 The tax-benefit systems under assessment are those in place as of June 2019.8 EUROMOD uses microdata from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). For this paper, we use the 2019 cross-sectional wave, comprising 2018 incomes. Uprating factors are used to bring the reported income values from the income reference period up to the policy year.

The use of microsimulation models for the analysis of MI schemes is relatively ample in the literature. While most studies use microsimulation modeling for estimating the extent of non-take-up (Bargain, Immervoll, and Viitamäki 2012; Fuchs et al. 2020; Matsaganis, Levy, and Flevotomou 2010), which can be substantial in several EU countries (Eurofound 2015), few studies use these estimates for correcting the simulation of these schemes toward a more “realistic” evaluation of their effects (one exception is the study of Matsaganis, Paulus, and Sutherland 2008 for 4 EU countries and the UK). The latter has to do with the challenging task of an appropriate identification of the real beneficiaries. As such, the common practice is to assume full take-up or, more comprehensively expressed, no simulation errors, as in the EU cross-country comparative studies by Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland (2013) or in Leventi, Sutherland, and Tasseva (2019).9 In this paper, however, we try to reconcile the simulations of the different EU MI schemes with the aggregate numbers collected and reported by each national administration. For this purpose, the first key question we investigate is how accurately the conditions to access these schemes are simulated in EUROMOD, which is crucial to determine the correct identification of potential beneficiaries. In line with the previous section, these conditions can be split into two broad categories: income-related conditions and non-income-related conditions.

Regarding the first category, income tests are generally simulated in EUROMOD with a high degree of accuracy given the availability of detailed income variables in EU-SILC. This means that we account for the different income sources included in the means-test of each scheme, while simulating any differential treatment to those incomes if explicitly designed by the law. However, two caveats apply. First, due to a lack of information about monthly incomes, the income test assumes that the annual income of the assessment unit is equally distributed throughout the 12 months. Thus, possible short entitlements to MI support might not be simulated, eventually leading to undersimulation. Second, to the extent that the detailed income variables in EU-SILC are subject to measurement errors (Trindade and Goedemé 2020), the subsequent simulations would be influenced accordingly. For instance, if an income source is misreported in the survey, this might result in simulating as entitled some units that would be otherwise not eligible. The opposite, although more unusual, could also happen and result in undersimulation. It is difficult to foresee whether the aforementioned issues lead to under or oversimulation, especially if they are simultaneously present in the data.

Regarding the second category, rules related to certain socio-demographic characteristics, for example, age-related requirements and family links between cohabitants, are simulated accurately since they are usually well-captured in EU-SILC. However, other non-income conditions can only be partially simulated. Typical examples include asset-related conditions10, time of residence in the country, registration at employment offices, or refusal to take up jobs. As a result, the number of beneficiaries in EUROMOD (and hence expenditure) is usually overestimated, that is, the model identifies as eligible some units that would not be entitled to the benefit if non-income conditions were simulated. Additionally, the model overestimates the number of beneficiaries because in reality not all entitled units do take up the benefits due to both demand-side factors (e.g., stigma, lack of information) and supply-side factors (e.g., discretionary rules applied by the administration, budgetary limitations).11 This overestimation has crucial implications when assessing the poverty-reducing effects of MI schemes, as not only the poverty-reducing impact of a country-specific scheme might be overestimated but the ordering of countries in a cross-country comparison might also significantly change depending on the extent of non-take-up (and/or the accuracy of the simulations) across countries.

To tackle the overestimation explained above, some country models in EUROMOD apply a benefit take-up adjustment to remove the beneficiary status to some simulated entitled families. However, this is done only in some countries (Belgium, Spain, Estonia, Finland, France, Croatia, Ireland, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Slovakia) and following different methodological approaches, varying from the application of available non-take-up estimates to the simulation of ad-hoc adjustments (e.g., disregarding beneficiaries entitled to small benefits).

4 A Methodology to Calibrate the Simulation of MI Schemes

The shortcomings of simulating MI schemes pose important problems not only for an accurate assessment of the effectiveness of existing MI schemes but also for a meaningful evaluation of possible reforms to these schemes. To do this, which is the focus of the next two sections, we start by applying a calibration procedure that corrects the existing simulations in EUROMOD, by matching the simulated outcomes of MI schemes with official statistics. The calibration is performed in a harmonized way for all EU countries to allow for a meaningful cross-country analysis. We therefore start by removing the ad hoc adjustments that are applied in EUROMOD for a few countries, as mentioned above, to obtain a “clean” baseline, representing the EUROMOD simulations without any adjustment to account for overestimation. We call this the “Full entitlement baseline.” We then apply our calibration procedure to this baseline to match the recorded official statistics and obtain a closer-to-reality “Calibrated baseline.”

4.1 The Choice of External Data

To calibrate the model, three main types of external data can be considered: take-up ratios, number of beneficiaries, and total expenditure. The first option would maintain relative consistency in EUROMOD but in practice, it is not feasible, as take-up rates are not available in a comparable and harmonized way across EU countries. The other two options have the advantage of being consistent with reality in absolute terms, accounting simultaneously for non-take-up and other simulation errors (e.g., the non-simulation of non-income conditions). Using the number of beneficiaries is less reliable than using expenditure, since there may be important conceptual and measurement differences across countries. For example, it is often not clear what the measurement unit reported in official statistics is (e.g., family heads, all individuals in the family or household), nor how they are counted (e.g., in a specific point in time or as an annual average). In contrast, total annual expenditure is a less ambiguous variable, typically corresponding to total spending on the scheme in the year. We therefore use it for the calibration, relying on the values reported by national experts in the EUROMOD Country Reports. The corresponding numbers for 2019 are presented in Table A2 of Appendix 1.

4.2 The Selection of MI Beneficiaries

Once has been computed for each household, an iterative algorithm is implemented in order to minimize our objective function. In practice, we define a calibration parameter that is sequentially decreased in 0.001 steps and confronted to . Then, for each subset of households whose , the resulting is calculated and the objective function is solved until the latter is minimized for an optimal parameter . This process is repeated for each EU country.

Importantly, is treated as an exogenous parameter, and different values can be selected to balance the importance of the deterministic and random components. Under a full deterministic approach, such that , only the poorest households will end up being selected as actual beneficiaries.13 With a random component, such that , other elements beyond the generosity of the entitlement will weigh in the probability. This implies that households entitled to a low benefit might eventually end up being selected as beneficiaries. As argued in the studies on the drivers of non-take-up (Hernanz, Malherbet, and Pellizzari 2004), although the generosity of the entitlement plays a crucial role in determining whether to claim a benefit, other non-monetary factors are also relevant (e.g., individuals living in rural areas are less likely to take up the benefit). Our random component roughly approximates these non-monetary elements.

We parsimoniously assume that for all individuals the weights of the random and deterministic components are the same, that is, . Naturally, the results are sensitive to this choice. Since our algorithm selects beneficiaries as to align with a fixed level of expenditure, setting a higher weight for the random component would imply selecting more actual beneficiaries entitled to lower benefits, and vice versa. In Sub-section 5.4, we assess how changing the values of influences our main results.

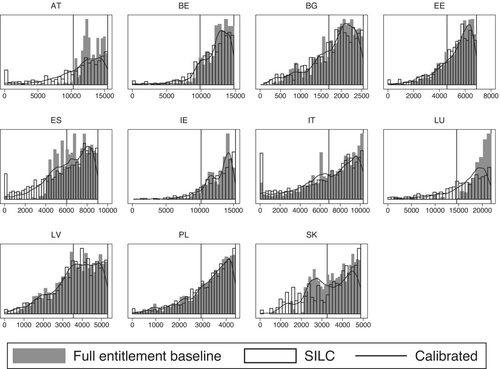

4.3 Validation of the “Calibrated Baseline”

We present the results of the calibration in Table A2 in Appendix 1, while in Table A3 we provide some country-specific comments on the simulation and calibration of each scheme. To assess the accuracy of the calibration, we consider the ratio of simulated expenditure in EUROMOD to the actual expenditure, the “validation ratio.” We compute this indicator both for the “Full entitlement baseline,” and the “Calibrated baseline.” Expenditure in the “Full entitlement baseline” is overestimated by at least 30% for 18 countries. For many of them, the ratios are equal to two or even higher (e.g., Ireland [8], Estonia [3.5], Spain [3.2], and Bulgaria [3.1]). As expected, in the “Calibrated baseline” all ratios are very close to one. For countries with underestimation (ratios below 1) before the calibration procedure, the calibration has no effect, since it just selects all the eligible individuals without reaching the target expenditure. In some cases, ratios are close to one, which might indicate simultaneously accurate simulations and low non-take-up. Others are clearly lower than one (Cyprus, Czechia, and Germany14). As previously mentioned, it may be that some caveats of the simulations performed in EUROMOD are more prevalent in these countries, such as the inability to capture short-term entitlements.15 The consequences of MI overestimation are shown in Appendix 2, Figure A1, which illustrates that, for some countries, the “Full entitlement baseline” substantially underestimates the occurrence of zero and very low incomes as compared to EU-SILC. In the following sections, we use the “Calibrated baseline” as the benchmark for presenting the results.

5 Assessing the Effectiveness of EU MI Schemes in Poverty Alleviation

Having developed a corrected baseline simulation, we can turn to an evaluation of the effectiveness of existing MI schemes as simulated in this baseline. We perform this evaluation considering three main interconnected dimensions: the coverage and adequacy of the schemes, and their poverty-alleviation effects. We focus on working-age individuals, defined as those aged between 16 and 64, both inclusive. Throughout the whole paper, the poor population is defined as individuals in working-age whose equivalized disposable income is below the poverty threshold. This threshold is defined according to an extreme poverty criterion, calculated as 40% of the median equivalized disposable income of the whole population. In Appendix 3, Figures A2-A7 we also provide the main results according to a standard poverty criterion, using a 60% poverty line.

5.1 Coverage

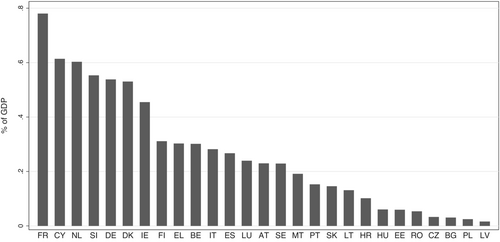

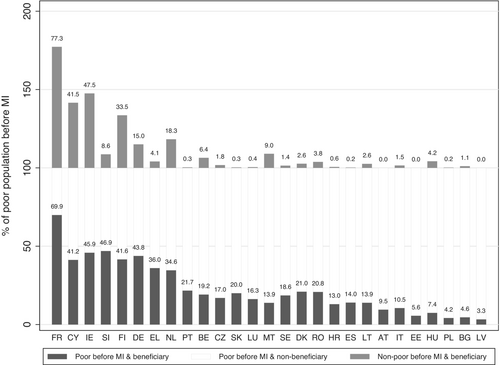

Figure 2 presents estimates of the percentage of individuals benefitting, or not, from MI support. A beneficiary is defined as any individual living in a household for which at least one MI scheme has been granted. Results are presented in percentage of the total poor population of each country, prior to MI support, to ease comparability and take into account the fact that this is the main target population of the benefit. Individuals are classified into three different types according to their poverty status and receipt of MI support: (i) individuals that are poor before MI support and are beneficiaries (poor beneficiaries); (ii) individuals that are not poor before MI support but still receive it (non-poor beneficiaries); and (iii) individuals that are poor before MI support but are not beneficiaries (poor non-beneficiaries). In our setting, we define coverage as the share of poor beneficiaries, regardless of whether they remain in poverty or are lifted out of it after MI receipt, over the total poor population before MI (dark gray bar).16

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD.

MI schemes depict a heterogeneous coverage across EU Member States. Coverage rates vary from 6.5% in Latvia to almost 90% in France. Most countries fail in covering the majority of the poorest population, with only nine countries depicting coverage rates above 50%. The three countries showing the highest coverage are Cyprus, France, and Ireland, whereas the three countries with the lowest coverage are Bulgaria, Latvia, and Poland. In countries with the highest coverage, between 10% and 20% of the poorest individuals are left without MI support, whereas in countries with the lowest coverage this percentage exceeds 90%.

Coverage rates are influenced by the restrictiveness of the eligibility conditions and the extent of take-up. In countries with low coverage, very restrictive MI thresholds are typically in place, as detailed in the next subsection, limiting access to only the most impoverished individuals. Additionally, these countries do not generally apply income disregards for employment income in the eligibility conditions, which may further contribute to the low coverage rates. The existence of conditions related to owner-occupied housing may also reduce coverage. For instance, while Bulgaria has eligibility conditions related to owner-occupied housing,17 these are not present in Cyprus and Ireland. In France, the high coverage is likely associated with the inclusion of an employment bonus as part of the MI scheme.

Two key issues should be considered when assessing coverage. First, the targeting of MI schemes is imperfect in relation to the (monetary) poverty criteria used. As can be seen in Figure 2, a substantial number of individuals are identified as MI beneficiaries despite not being identified as poor (light gray bar), especially in countries that show high coverage rates, like France, Finland and Ireland. In some cases, the share of non-poor beneficiaries is as large, or even larger, as the share of poor non-beneficiaries, potentially suggesting a misallocation of MI support with respect to a strict (monetary) poverty criterion. This misalignment is largely due to MI thresholds being set above the 40% poverty line. When poverty is measured using a 60% poverty line, the extent of non-poor beneficiaries decreases (Figure A2 of Appendix 3).18

Second, broadening the definition of MI protection to include other schemes beyond our selection of “core” MI schemes would generally increase coverage in most countries, as shown in Table A7 of Appendix 5. This effect can be substantial in countries with very low coverage rates, such as Bulgaria, leading to some re-ranking within the EU. For instance, when housing benefits are taken into account, Bulgaria's coverage rate rises by more than 50 pp. However, even when accounting for all means-tested benefits, some countries, such as Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, still show low coverage rates.

5.2 Adequacy

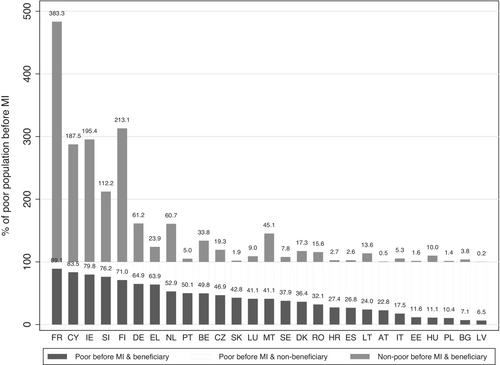

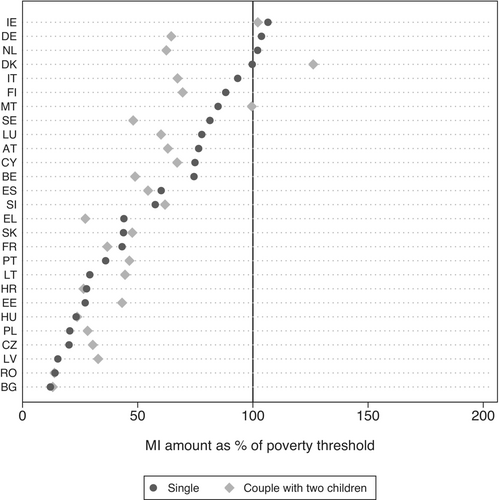

We now move to the assessment of the adequacy, that is, how generous MI schemes are. For this, we consider two approaches. The first approach is to use EUROMOD's Hypothetical Household Tool (HHoT), to assess adequacy for two “typical” household types, based solely on the rules of the tax-benefit system, without accounting for data-driven heterogeneities.19 The idea is to assess the level of adequacy across the EU in a comparative way, considering two households with the same characteristics in all countries. We select a single adult and a couple with two children as the two household types. Both units are jobless households, where all adults have been unemployed for the last 18 months, are actively seeking a job, and live in a rented accommodation.20 This definition aims to approximate the maximum amount of the benefit that potential candidates to MI support could receive, triggering the simulation of the assessed MI schemes in EUROMOD.21 Figure 3 presents the resulting MI amounts as a share of each country-specific poverty line.

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD

.More than half of EU countries provide MI amounts that are not adequate with respect to an extreme poverty criterion, that is, the MI amount as a percentage of the 40% poverty line falls below 100%. In particular, the generosity of the schemes in Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, and Romania is very low (below 40% for a single adult). Notably, in Bulgaria, Czechia, and Hungary, MI amounts are not adjusted regularly over time, but its indexation depends on political cycles and priorities, as well as the availability of resources (European Commission 2022a).22 On the contrary, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Malta, and the Netherlands provide high levels of adequacy, above 120% for a single adult.

Looking at the differences between the two types of households, we find that in many countries the adequacy of MI support is lower for larger family units. With some exceptions, a couple with two children generally receives a less adequate benefit than a single adult. Two considerations are relevant here. The first relates to the use of the OECD-modified scale as an equivalence scale. According to this scale, a couple with two children aged below 14 years old should be able to spend 110% more than a single adult (50% for the partner, 30% for each child). Thus, to maintain the same adequacy level as of a single adult, MI amounts for a couple with two children should be at least 110% higher. However, our results suggest that the implicit equivalence scales of most EU MI schemes do not adequately address these additional needs, as measured by the OECD-modified scale. While this scale is widely accepted by researchers, it somewhat arbitrarily assigns values to the additional needs of family members. In reality, these needs vary according to a diverse variety of characteristics, including income (Garbuszus et al. 2021). More sophisticated approaches, such as those relying on expenditure data (e.g., Bargain and Donni 2012) or on the cost of goods and services required to meet basic needs (e.g., Penne et al. 2020), could be explored as alternatives.

A second consideration relates to complementary benefits. As previously discussed, it is often the case that alternative benefits complement MI provisions, thus increasing the adequacy (and coverage) of public cash support for low-income households. Child-related benefits, for example, are often provided in addition to MI benefits, with the former typically not being considered in the means-tests for the latter. As with coverage, we account for a broader range of schemes, beyond our identification of core MI schemes, and provide additional indicators of adequacy in Table A7 of Appendix 3. We find that the adequacy levels increase in several countries due to other complementary benefits, particularly child-related benefits, but that the increase remains limited in several countries (e.g., Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, and Romania) or is even zero in others (e.g., Italy, Spain).

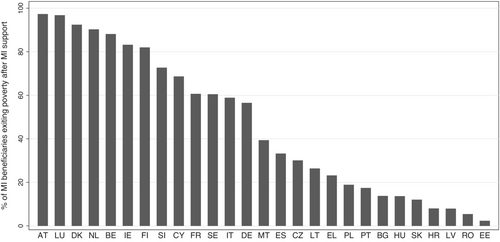

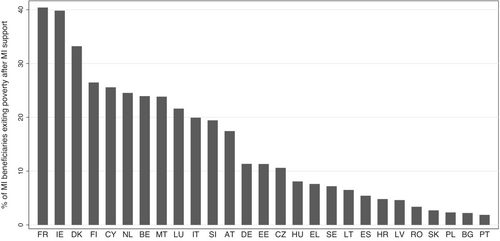

The second approach we use to measure adequacy involves considering the specific characteristics of households receiving MI schemes in our calibrated data. In line with Figari, Matsaganis, and Sutherland (2013), we define adequacy as the share of poor individuals receiving MI schemes with equivalized disposable income above the poverty line. Figure 4 shows that in half of the countries, less than 50% of poor beneficiaries exit poverty after receiving the MI support. Only Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands show a high level of adequacy, above 90%. At the other extreme, in countries such as Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, and Romania, adequacy levels are very low, below 10%. These findings are consistent with those presented above, based on hypothetical households with predefined characteristics (Figure 3), and highlight that in most Central Eastern European countries and in some Southern European countries MI amounts are typically not adequate with respect to an extreme poverty criterion.

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD

.5.3 Poverty-Alleviation Effects

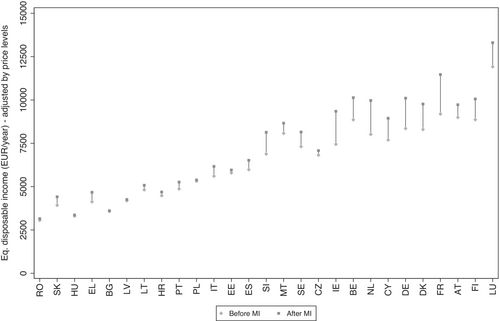

To the extent that countries offer a good combination of coverage and adequacy, this should translate into higher disposable incomes for the poorest individuals. Figure 5 depicts the mean annual equivalized disposable income of poor individuals before and after receiving MI support. Results account for the different price levels across EU Member States by dividing the nominal values (EUR) by the Price Level Index of each country as reported by Eurostat, to ease the comparability across countries. Averages are calculated for all poor individuals, independently of whether they receive MI support.

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD and Eurostat data on price levels (2019)

.Before MI support, the equivalized disposable income of individuals in extreme poverty varies significantly across EU Member States, from 2000 to 6800 EUR per year (in real terms), reflecting the different socioeconomic conditions across EU countries before the last-resort safety nets took effect. The lowest values can be observed in Hungary, Greece, Romania, and Slovakia, while the highest ones correspond to Austria, Finland, France, and Luxembourg.

Remarkably, MI schemes do not enable the convergence of disposable incomes of the poorest citizens across the EU, as the best-performing countries before MI support are also those achieving the highest increases in disposable incomes due to MI support. In particular, the support provided by Belgium, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands is particularly effective at improving the income conditions of the poorest citizens, whereas Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia, and Romania's schemes barely entail any increase in average terms. This result aligns with the low coverage rates and adequacy levels found for the “core” MI schemes of these countries.

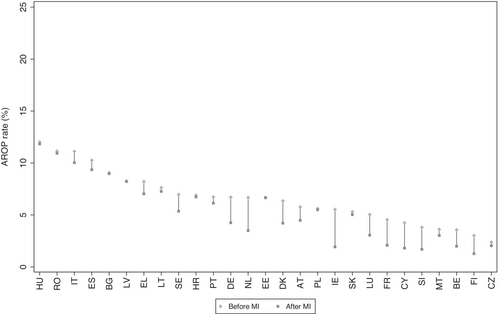

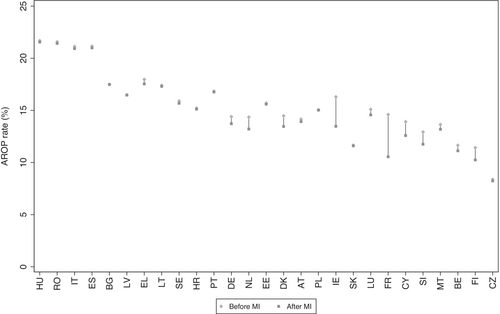

A complementary approach to evaluate the effectiveness of MI schemes in improving the income conditions of the poorest individuals is to look at poverty-related indicators. Figure 6 shows at-risk-of-poverty (AROP) rates before and after MI support for all EU countries. This indicator measures poverty incidence, that is, the share of the population with an equivalized disposable income below the poverty line. The poverty line is calculated based on the equivalized disposable income excluding MI support. Intuitively, we anchor the poverty line to the counterfactual scenario “before MI support” in which MI schemes are not in place.

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD

.In most EU countries, MI support seems insufficient to lift beneficiaries out of poverty, with reductions in AROP rates generally remaining below 1 pp. However, there are notable exceptions, including Cyprus (−2.4 pp), France (−2.5 pp), Germany (−2.5 pp), Ireland (−3.6 pp), and the Netherlands (−3.2 pp).23

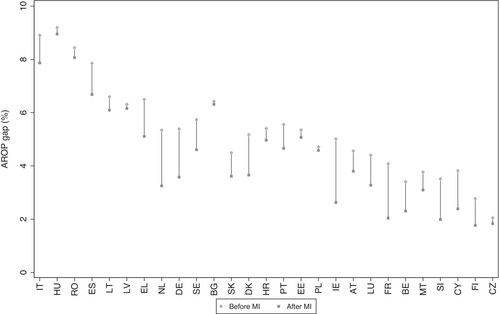

Figure 7 shows a second measure of poverty, AROP gaps, before and after MI support for all EU Member States. This indicator measures the intensity of poverty, that is, the mean shortfall in income from the poverty line, in percentage of the latter. Although existing EU MI schemes may not be sufficient to lift beneficiaries out of poverty, they do reduce the shortfall in income from the poverty line. Once again, there is significant heterogeneity across EU MI schemes, with a few countries reducing AROP gaps by more than 1 pp (e.g., Germany, Greece, Ireland, and the Netherlands), whereas others achieve only small reductions (e.g., Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Latvia, and Poland).

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD

.5.4 Evaluating Alternative Calibrations for Selecting MI Beneficiaries

For the main results of this paper, we parsimoniously assign the same weight to the deterministic and the random components, setting w = 0.5. Here, we assess to what extent the value assigned to parameter influences our results, considering two additional calibrated scenarios (CS): (i) “Full random assignment” (), such that , scenario CS1; (ii) “Full deterministic assignment” , with higher probability of receiving a benefit for lower income households, such that , scenario CS2. The literature on the determinants of the take-up rate (e.g., Van Oorschot 1991) suggests that the probability of claiming a benefit positively correlates with the size of the benefit (i.e., w < 1, and P = . Hence, we would expect that the real scenario lies somewhere between CS1 and CS2.

Table 2 shows differences in coverage rates with respect to the baseline. First, we present the “Full entitlement baseline” to underscore that this scenario substantially overestimates coverage in most EU countries. Recall that this scenario informs on the potential impact of MI support under full take-up, although it might be influenced by the absence or partial simulation in EUROMOD of certain eligibility conditions to access MI support. The largest differences between our default calibration (w = 0.5) and the “Full entitlement baseline” are observed in Austria, Luxembourg, Slovakia, and Spain. As explained in Section 3, these differences might be attributed both to the absence or partial simulation of certain rules to access MI support24, and high non-take-up rates. For instance, in Luxembourg, due to a lack of information, wealth-related requirements are not simulated in EUROMOD. Similarly, in Austria, the asset test is only partly simulated. In Spain, conditions such as job-seeker registration, application for other benefits before seeking MI support, or not owning secondary residences cannot be simulated with precision.25 Additionally, existing studies indicate substantial non-take-up rates in these countries (Amétépé 2012; Eurofound 2015; Fuchs et al. 2020).

| Difference w.r.t the baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibrated scenarios | ||||

| CS1: “Full random assignment” | CS2: “Full deterministic assignment” | |||

| Country | Baseline (w = 0.5) | “Full entitlement baseline” (no calibration) | (w = 1) | (w = 0) |

| AT | 23 | 75 | 11 | −6 |

| BE | 50 | 42 | −14 | 9 |

| BG | 7 | 22 | 2 | −1 |

| CY | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CZ | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DE | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DK | 36 | 13 | −7 | 5 |

| EE | 12 | 43 | 5 | 0 |

| EL | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ES | 27 | 47 | 10 | −1 |

| FI | 71 | 26 | −9 | 17 |

| FR | 89 | 1 | −7 | 0 |

| HR | 27 | 1 | 1 | −2 |

| HU | 11 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| IE | 80 | 9 | −6 | −1 |

| IT | 18 | 26 | 3 | −1 |

| LT | 24 | 6 | 0 | −1 |

| LU | 41 | 45 | 0 | −7 |

| LV | 6 | 15 | 3 | −1 |

| MT | 41 | 21 | 6 | 0 |

| NL | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PL | 10 | 27 | 6 | 0 |

| PT | 50 | 12 | 8 | −6 |

| RO | 32 | 9 | −1 | 1 |

| SE | 38 | 23 | 4 | −3 |

| SI | 76 | 18 | 1 | 8 |

| SK | 43 | 48 | −2 | −4 |

- Note: Difference in percentages points with respect to our default calibration scenario (w = 0.5).

- Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD.

Next, we examine the impact of the alternative calibrated scenarios, CS1 and CS2. Compared to our baseline calibration (w = 0.5), CS2 typically involves selecting fewer but poorer beneficiaries, leading to lower coverage rates, while CS1 produces coverage rates that are generally similar to or higher than the baseline calibration. These findings reflect the influence of the deterministic component, , in determining the probability to be selected as actual MI beneficiary. However, there are some exceptions. In countries like Finland, Denmark or Belgium, our default calibration (w = 0.5) includes many non-poor beneficiaries (see Figure 2), whereas CS2 tends to select poorer beneficiaries. As coverage is calculated as a proportion of poor individuals, this results in higher coverage rates under CS2 than in the baseline for these countries. Conversely, for CS1, we observe the opposite: in Belgium, Finland, Denmark, and other few countries, some poor beneficiaries included in our default calibration may be excluded under a full random assignment, leading to lower coverage than in the baseline. Despite these exceptions, CS1 and CS2 do not show large differences across most EU countries when compared to our default calibration.

Similar comparisons can be made based on additional indicators. In Appendix 2, Tables A5 and A6, we present the results on adequacy and poverty, respectively. Regarding adequacy, recall that we measure it through the share of poor individuals receiving MI schemes whose equivalized disposable income rises above the poverty line. As this indicator is limited to MI beneficiaries in poverty, it is not affected by the possible selection of non-poor individuals. While it shows some variability especially depending on other characteristics beyond income, such as household type (e.g., single or couple with children) or the level of assets owned, it is not that sensitive to the changes between different calibrated scenarios.26 Regarding poverty, CS2 tends to produce lower AROP gaps compared to the baseline, because of the selection of MI beneficiaries who typically exhibit higher poverty gaps and are therefore entitled to higher MI amounts. On the contrary, CS1 generally results in higher AROP gaps compared to the baseline. The variation in AROP rates is mostly stable, and we do not observe substantial discrepancies with respect to the default calibration. Changes in AROP rates across different calibrations largely depend on how transitions around the poverty threshold take place. In countries where the adequacy of the MI schemes is not sufficient to lift beneficiaries out of poverty, calibrating via the use of different values of our parameter w does not entail significant changes in AROP rates, as the equivalized disposable income of MI beneficiaries remains below the poverty threshold.

6 Exploring Possible Reforms to Existing MI Schemes

In light of the low effectiveness of existing MI schemes in poverty alleviation in several EU countries, we explore the simulation of possible reforms. We consider changes to the two main elements defining the performance of MI schemes: coverage and adequacy. The reforms considered are theoretical, focused on the working-age population, and not targeted at changing country-specific aspects of the MI scheme of each country. The goal of the simulations is not to provide a comprehensive analysis of all the possible reforms that could be considered by authorities in each country but rather to: (i) provide a methodological framework to think about the main aspects that should be considered when reforming MI schemes; (ii) show how far/close the current MI scheme for each EU country is from eradicating extreme poverty; and (iii) show how this would change if adequacy (first) and coverage (second) improved.

6.1 The Reform Scenarios: Description and Rationale

We simulate a new hypothetical complementary MI scheme, which works as a last-resort safety net for the poorest households, complementing their equivalized disposable incomes up to each country-specific extreme poverty line. The eligibility to the new complementary scheme is only made on a purely monetary basis, with no additional criteria being considered (i.e., there are no age-related criteria, wealth tests, or other requirements potentially excluding those in extreme monetary poverty from being eligible for the complement). The unit of assessment is the household, and thus the incomes of all cohabiting individuals are pooled together regardless of their family links. This differs with respect to most MI schemes in EU Member States, where the unit of assessment usually uses a narrower concept (i.e., cohabiting individuals linked by family relations up to a specific degree).27 The scheme operates after the simulation of all taxes and benefits, including each existing country-specific MI scheme(s). Hence, the final benefit amount is not taxable, nor included in other means-tested benefits. The amount of the complementary MI support for each household is calculated as the difference between households' equivalized disposable income and each country-specific extreme poverty line.28

Once the new scheme is simulated, we restrict its accessibility to three different populations of interest by considering three possible reform scenarios, following a stepwise approach. First, the new complementary MI scheme is only assigned to the current beneficiaries of each country's existing MI scheme. Therefore, if the current MI scheme is not adequate to bring the corresponding beneficiary household out of extreme poverty, the new MI scheme financially complements this household's disposable income up to the 40% poverty line. Beneficiaries already receiving an adequate amount are not complemented further. This scenario (“Increased adequacy” scenario, hereinafter) shows the impact of increasing the generosity of the MI entitlement for the current beneficiaries in poverty by the amount needed to lift them out of extreme poverty. Second, and in addition to the previous scenario, we assign the new complementary MI scheme to a specific number of individuals in extreme poverty who were not receiving the existing country-specific MI scheme such that the coverage rate of MI support increases by 10 pp.29 This scenario (“Increased coverage” scenario, hereinafter) shows the effects of reaching a higher proportion of those in need by increasing the number of beneficiaries of MI support.30 Third, the new complementary MI scheme is provided to all poor households that had not been selected as beneficiaries in the previous two scenarios. This final scenario (“Extreme poverty elimination” scenario, hereinafter) measures the impact of eliminating extreme poverty in each country and provides a benchmark to which the current MI scheme and the previously simulated scenarios can be compared to.

The results from these simulations are then compared with the ones for the “Calibrated baseline,” as presented in Section 5.31 Importantly, our results should be interpreted as “morning-after effects,” as we abstract from potential behavioral responses triggered by the simulated reforms. These responses might distort the outcomes of a specific policy change, moving away from the original objectives. Regarding MI schemes, behavioral responses usually refer to labor supply disincentives (see, for instance, Bargain and Doorley 2011), justifying the introduction of accompanying labor activation strategies (e.g., participation in training programs, tailored assistance with job vacancies). Furthermore, our results do not capture potential consumption and saving behavioral reactions that might occur as a response to changes in households' disposable incomes (see, among others, Nelson 2012, on the relationship between minimum income levels and material deprivation).

6.2 What Improvements in the Living Standards of Poor Households?

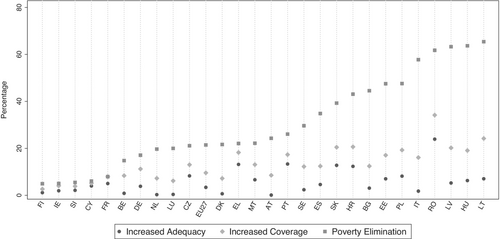

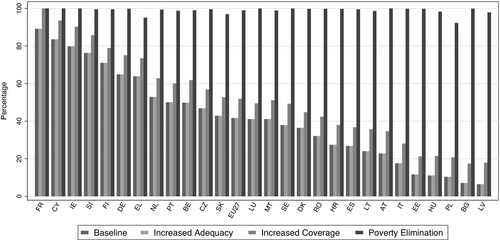

We now focus on households whose income falls below the extreme poverty line, despite the existing MI schemes. Figure 8 shows the percentage change in the mean annual equivalized disposable income of individuals in extreme poverty implied by each reform scenario relative to the baseline.

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD

.The average equivalized disposable income of individuals in extreme poverty for the EU27 would increase by 4.1% in the “Increased adequacy” scenario, with significant variation across EU Member States. In some countries like Hungary, Lithuania, Portugal, and Romania, an increase in adequacy would imply a non-negligible increase in household disposable income, between 15% and 25%. This is not surprising, since these countries were among those performing worst in terms of adequacy. In contrast, in countries like Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, which already had a high adequacy in the baseline scenario, an increase in adequacy would barely rise disposable income.

When considering an increase in both adequacy and coverage, that is, the “Increased coverage” scenario, the EU27 average equivalized disposable income of individuals in extreme poverty would increase by 9.4%, again with significant heterogeneity. In countries like Hungary, Lithuania, Portugal, and Romania, the increase would be between 23% and 33%, suggesting that in these countries there might be room for enhancing the targeting of these schemes via the promotion of the take-up and/or the adjustment of the eligibility criteria toward the inclusion of those in monetary extreme poverty. On the contrary, in countries like Finland, Ireland, and Slovenia, the increase would be below 4%, suggesting that the potential of reforms to existing MI schemes in increasing poor households' disposable income is somewhat limited.

Finally, the average equivalized disposable income of EU27 poor individuals would increase by 20.1% in the “Poverty elimination” scenario, reflecting both the change in the level of the benefit for current beneficiaries and the access to the new adequate entitlement for previously excluded individuals. As before, there would be significant differences across countries, with some countries such as Hungary, Lithuania, and Romania having increases around 60%, and other countries like Cyprus, Ireland and Finland having increases below 6%.

Figure 9 shows the AROP gaps in the baseline and in each reform scenario. The relative impacts of increasing adequacy and coverage differ substantially across countries. In some countries, such as Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Italy, an increase in adequacy to the poverty line would lead to an only negligible decrease in the degree of poverty intensity. An increase in coverage by 10 pp., however, would lead to a substantial decrease in the AROP gap. In other countries, such as Greece, Romania, and Slovakia, the opposite is true, with an increase in adequacy being more effective at reducing the distance between the income of poor individuals to the poverty line. Taken together, these two hypothetical reforms substantially impact the AROP gap in most countries, decreasing its level at the EU27 average by 0.7 pp., with five countries (Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania and Romania) achieving reductions exceeding 1 pp. Increasing coverage to target poverty elimination would bring the AROP gaps close to zero in all countries.32 For most countries, a substantial decrease in the AROP gap would be achieved in this third scenario, suggesting that efforts toward reaching excluded households from MI support would be the key element of potential reforms.

Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD

.6.3 How Far From Extreme Poverty Eradication?

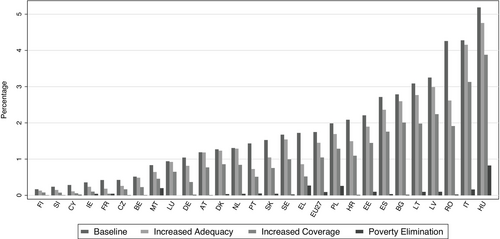

Table 3 shows the total expenditure on existing MI schemes, as a percentage of GDP, as well as the expenditure changes implied by our reform scenarios, in pp with respect to the “Calibrated baseline.”

| Diff. w.r.t baseline (pp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | “Calibrated baseline” (% GDP) | “Increased adequacy” scenario | “Increased coverage” scenario | “Extreme poverty elimination” scenario |

| AT | 0.23 | +0.00 | +0.06 | +0.17 |

| BE | 0.30 | +0.00 | +0.04 | +0.07 |

| BG | 0.03 | +0.03 | +0.10 | +0.35 |

| CY | 0.61 | +0.03 | +0.04 | +0.05 |

| CZ | 0.03 | +0.02 | +0.03 | +0.05 |

| DE | 0.54 | +0.03 | +0.10 | +0.15 |

| DK | 0.53 | +0.01 | +0.05 | +0.17 |

| EE | 0.06 | +0.04 | +0.11 | +0.29 |

| EL | 0.30 | +0.10 | +0.14 | +0.16 |

| ES | 0.27 | +0.05 | +0.13 | +0.34 |

| FI | 0.31 | +0.01 | +0.01 | +0.02 |

| FR | 0.78 | +0.03 | +0.05 | +0.05 |

| HR | 0.10 | +0.07 | +0.12 | +0.27 |

| HU | 0.06 | +0.04 | +0.12 | +0.39 |

| IE | 0.45 | +0.01 | +0.02 | +0.03 |

| IT | 0.28 | +0.02 | +0.14 | +0.51 |

| LT | 0.13 | +0.04 | +0.13 | +0.35 |

| LU | 0.24 | +0.00 | +0.03 | +0.10 |

| LV | 0.02 | +0.03 | +0.12 | +0.39 |

| MT | 0.19 | +0.02 | +0.05 | +0.08 |

| NL | 0.60 | +0.00 | +0.06 | +0.17 |

| PL | 0.02 | +0.04 | +0.08 | +0.19 |

| PT | 0.15 | +0.08 | +0.10 | +0.15 |

| RO | 0.05 | +0.13 | +0.19 | +0.35 |

| SE | 0.23 | +0.01 | +0.08 | +0.20 |

| SI | 0.55 | +0.01 | +0.02 | +0.03 |

| SK | 0.15 | +0.05 | +0.09 | +0.16 |

| EU27 | 0.43 | +0.03 | +0.09 | +0.20 |

- Note: EU27 stands for the GDP weighted EU average.

- Source: Our own elaboration using EUROMOD and Eurostat data on GDP (2019).

At the EU27 average level, moving to the “Increased adequacy” scenario entails an increase in the expenditure to GDP ratio of ~0.03 pp., reflecting the higher amounts of MI support implied by moving all MI beneficiaries to each country-specific extreme poverty line. An increase in expenditure is observed in all countries, but the values of these increases are highly heterogeneous. They are particularly high in Croatia, Greece, Portugal, and Romania suggesting that the provision of more generous amounts to the current beneficiary households in those countries could have significant budgetary consequences.

Moving to the “Increased coverage” scenario, we observe an increase in the EU27 expenditure to GDP ratio of ~0.10 pp. relative to the baseline scenario. The increase in coverage rates is, therefore, more costly than the increase in adequacy levels. At the country level, the increases in expenditure are once again highly heterogeneous, varying from 0.01 pp. in Finland, where the initial coverage rate is among the highest in the EU, up to 0.19 pp. in Romania, whose initial coverage is less well targeted.33

Finally, considering the “Poverty elimination” scenario, the expenditure to GDP ratio for the EU27 average would increase from 0.43% to 0.63%. In other words, to achieve “Poverty Elimination” the increase in expenditures would be of 0.20 pp. relative to the baseline, illustrating that the additional cost of providing MI support to lift all poor households in the EU out of poverty would be low.34 For some countries, such as Cyprus, Finland, France, Ireland, and Slovenia, the additional expenditure would be rather small, suggesting that poverty elimination would require a relatively marginal effort. For others, such as Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Spain, and Romania, the increase in expenditure would vary between 0.30 pp. and 0.55 pp., indicating that complete poverty elimination could be a somewhat more ambitious objective given the existing coverage and adequacy levels.

As previously mentioned, our estimates must be interpreted as pure “morning-after” effects, with two important caveats applying: first, as shown by Collado et al. (2016), if work incentives are to be considered such that the existing participation tax rates remain unchanged, the cost of lifting individuals out of poverty would be significantly higher. In this sense, our estimates only represent lower bounds of the real costs these (theoretical) reforms would have. Second, and even in the presence of negative labor supply responses, an extended provision of MI support could also have some self-financing properties if currently social excluded individuals are eventually reintegrated into the labor market, for example, by means of the activation inclusion elements usually embedded within these schemes (Marchal and van Mechelen 2017). Hence, a comprehensive evaluation of the fiscal viability of eradicating extreme poverty should ideally consider these two elements and adopt a more dynamic approach, including macroeconomic feedback effects (Barrios et al. 2019).

7 Conclusion and Discussion

MI schemes are an important tool available to policymakers to alleviate poverty and fight social exclusion, by guaranteeing a last-resort safety net for households with insufficient resources. An accurate assessment of the effectiveness of these schemes in terms of their design and reach is crucial to identify potential gaps and avenues for reforms. Despite its relevance, this assessment faces several data and modeling limitations, which often lead to an under or overestimation of the extent of MI support, and to a bias in the measurement of the real impact of this support on disposable incomes and poverty.

In this paper, we attempt to provide an integrated and consistent evaluation of the effectiveness of MI schemes in poverty alleviation in the EU in three main steps. First, we apply a new method to calibrate the simulation of MI schemes in the microsimulation model EUROMOD, to tackle the limitations of the model and obtain a new “closer to real spending” baseline simulation of each EU Member State's scheme(s). Second, we use this corrected baseline to evaluate existing MI schemes, investigating their degree of coverage and adequacy, their impacts on poverty, and their overall cost. Third, we explore the effects of possible (theoretical) reforms, implementing sequential changes to the levels of coverage and adequacy, and calculate the “morning-after” budgetary cost of extreme poverty elimination.

Our results suggest that the coverage rate of existing MI schemes is quite heterogeneous across EU countries but generally insufficient, with most countries reaching less than 50% of households in extreme poverty and some having coverage rates even below 10%. Intuitively, this might explain why during the COVID-19 crisis several countries felt the need to implement temporary schemes for social assistance and other discretionary measures (see e.g., Christl et al. 2024), somewhat calling into doubt the potential automatic stabilization properties of existing MI schemes. Moreover, we find that the benefit levels provided by existing schemes are not adequate to provide a minimum standard of living in more than half of the EU countries, with the generosity of the support being below 50% of the extreme poverty line in several countries. Furthermore, the adequacy of MI support is often lower for larger families vis-à-vis single-person households. This suggests that the complementary amounts provided for children through MI support may be insufficient to adequately cover the expenses of raising them. While many EU countries ensure adequate income levels for families with children by providing additional child-related benefits alongside MI support, in some countries the combined support remains insufficient. The combination of the different coverage and adequacy levels across EU countries results in heterogeneous effects on poverty alleviation. Remarkably, MI schemes do not enable the convergence of disposable incomes of the poorest citizens across the EU, as the best-performing countries before MI support are also those with the highest increases in disposable incomes through MI support. In addition, MI support in most EU countries seems insufficient to lift beneficiaries out of poverty. Nevertheless, it does play an important role in reducing the shortfall in incomes from the poverty line.

There is scope for overcoming some of the gaps in current MI schemes through reforms affecting both the coverage and adequacy of these schemes. Although with high heterogeneity across EU countries, our results suggest that extending the coverage to all poor households in working-age, such that extreme poverty is fully eliminated, would imply an overall additional cost of 0.20 pp. relative to the expenditure to GDP ratio produced by existing MI schemes, at the EU level. Therefore, the additional “morning-after” cost of providing MI support to lift all poor households in the EU out of poverty (relative to the status quo) would be rather low, and arguably far from unattainable.

The analysis performed in this paper provides a framework to think about the main aspects to consider when evaluating and reforming MI schemes and gives fresh insights into the effectiveness of current MI schemes in the EU and possible ways to reform them. The main takeaways are that the contribution of MI support to poverty elimination is still rather limited in some EU countries and that action could be taken to increase coverage and adequacy, moving toward poverty elimination, at a relatively low budgetary cost. Implementing these changes can be achieved through different means: enabling better accessibility to the MI schemes (e.g., promoting take-up by improving access to information, decreasing bureaucratic procedures, fighting stigmatization), softening the eligibility criteria (e.g., perhaps reconsidering the role of asset tests35 and other non-income conditions, such as minimum age), moving toward a closer consideration of adequacy vis-à-vis poverty thresholds, and so forth. Our analysis also discusses the importance of the definition of MI schemes when assessing their poverty effects. While in some countries coverage rates increase significantly when considering a broader definition of MI protection, in other countries these rates are almost unaffected.

Despite its potential usefulness, the analysis is, naturally, not without limitations. First, our results are pure “morning-after” effects, abstracting from any possible behavioral reactions to the simulated reforms. Indeed, our approach only sets up a static benchmark to assess the current performance of MI schemes and how this would change under policy reforms aimed at increasing their adequacy and coverage. A more comprehensive assessment should incorporate a dynamic approach, with a concrete focus on behavioral reactions, both from supply (e.g., labor supply effects) and demand (e.g., changes in consumption and savings) perspectives. Second, the reforms considered are theoretical and do not account for any country-specific aspects of the design of MI schemes, simply exploring the effects of changing coverage and adequacy in a uniform way for all countries. A more complete and informative analysis should provide a discussion and evaluation of the different reform possibilities available for each country based on the characteristics of the country's scheme. Finally, the results are sensitive to the approach adopted for the calibration of the new baseline. A more accurate analysis should perform more refined calibrations considering the availability of more disaggregated data at country-specific levels.

The above-discussed limitations provide important avenues for future research. In particular, considering behavioral effects on work incentives and consumption reactions to MI reforms would be an important step toward a more comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of MI schemes. In the same vein, the simulations could be extended to include not only cash transfers but also in-kind benefits, such as free childcare, which in some countries may play an important role in ensuring a minimum living standard.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are purely those of the authors and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The results presented here are based on EUROMOD version I3.86+. Originally maintained, developed, and managed by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER), since 2021, EUROMOD has been maintained, developed, and managed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission in collaboration with Eurostat and national teams from the EU countries. We are indebted to many people who have contributed to the development of EUROMOD. The results and their interpretation are the authors' responsibility. We acknowledge the fruitful comments of Ana Agúndez, Anna Burger, Olivier Bontout and Viginta Ivaškaitė-Tamošiūnė, and of the participants of the XXIX Meeting on Public Economics, the EUROMOD Annual Meeting and Research Workshop 2022, the OECD Applied Economics Work-in-Progress Seminar, and the 10th Meeting of the Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ). Comments from anonymous referees are also gratefully acknowledged. We immensely thank Fidel Picos for his valuable insights and support with the methodology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Appendix 1: List of MI Schemes and Validation Results

| Country | MI scheme as in MISSOC | EUROMOD policy | Target group |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT | Guaranteed minimum resources (Mindestsicherung) | bsa_at | Working-age and elderly |

| BE | Integration income (Revenu d'intégration/leefloon) | bsa_be | Working-age |

| Guarantee of income for elder persons (garantie de revenus aux personnes âgées/inkomensgarantie voor ouderen) | Elderly | ||

| Income Replacement Allowance (allocation de remplacement de revenus/inkomensvervangende tegemoetkoming) | Special case (disability) | ||

| Integration Allowance (allocation d'intégration/integratietegemoetkoming) | Special case (disability) | ||

| Allowance for Assistance to the Elderly (allocation pour l'aide aux personnes âgées/tegemoetkoming voor hulp aan bejaarden) | Special case (elderly care) | ||

| BG | Social assistance allowances (Месечни социални помощи) | bsa00_bg | Working-age and elderly |

| Social pension for old-age (Социална пенсия за старост) | Elderly | ||

| CY | Guaranteed Minimum Income (Eλάχιστo Eγγυημένo Eισόδημα) | bsamm_cy | Working-age and elderly |

| Social Pension (Koινωνική ∑νταξη). | Elderly | ||

| Scheme supporting pensioners' households with low income (∑χέδιo ενίσχυσης νoικoκυριν συνταξιoχων με χαμηλά εισoδήματα) | Elderly | ||

| CZ | Allowance for Living (Příspěvek na živobytí) | bsa_cz | Working-age and elderly |

| Supplement for Housing (Doplatek na bydlení) | Special case (housing) | ||

| Extraordinary Immediate Assistance (Mimořádná okamžitá pomoc) | Special case (extraordinary circumstances, e.g., natural disaster) | ||

| DE | Subsistence benefit (Hilfe zum Lebensunterhalt) | bsa00_de | Working-age and elderly |

| Unemployment assistance for jobseekers (Grundsicherung für Arbeitsuchende) | bunnc_de | Working-age | |

| Assistance for the elderly and for persons with reduced earning capacity (Grundsicherung im Alter und bei Erwerbsminderung) | Elderly and special case (disability) | ||

| DK | Social assistance (kontanthjælp) | bsa_dk | Working-age |

| Integration benefits (integrationsydelse) | Special case (integration of non-residents, e.g., refugees) | ||

| Educational assistance (uddannelseshjælp) | Special case (students) | ||

| EE | Subsistence benefit (toimetulekutoetus) | bsa00_ee | Working-age and elderly |

| Unemployment allowance (töötutoetus) | Working-age | ||

| Allowance for old-age pensioner living alone (üksi elava pensionäri toetus) | Elderly | ||

| EL | Social Solidarity Income (“SSI”) (KOINΩNIKO EI∑OΔHMΑ ΑΛΛHΛEΓΓYH∑) | bsa00_el | Working-age and elderly |

| Social solidarity allowance for uninsured elders (EΠIΔOMΑ KOINΩNIKH∑ ΑΛΛHΛEΓΓYH∑ ΑNΑ∑ΦΑΛI∑TΩN YΠEPHΛIKΩN) | Elderly | ||

| ES | Regional Minimum Income Schemes (Rentas Mínimas de Inserción) | bsarg_es | Working-age |

| Minimum Living Income (Ingreso Minimo Vital) | bsa00_es | Working-age | |

| Non-contributory old-age benefit (Pensión de jubilación no contributiva) | Elderly | ||

| Non-contributory invalidity benefit (Pensión de invalidez no contributiva) | Special case (disability) | ||

| Unemployment assistance (desempleo de nivel asistencial) | Working-age | ||

| Minimum for Spanish persons residing abroad and returnees (Prestación por razón de necesidad a favor de los españoles residentes en el exterior y retornados) | Special case (integration of non-residents, e.g., refugees) | ||

| FI | Basic Social Assistance (Perustoimeentulotuki) | bsa00_fi | Working-age and elderly |

| FR | Active solidarity income (revenu de solidarité active, RSA) | bsa00_fr | Working-age |

| Employment bonus (Prime d'activité) | bsawk_fr | Working-age | |

| Allowance for disabled adults (allocation pour adulte handicapé, AAH) | Special case (disability) | ||

| Solidarity allowance for the elderly (allocation de solidarité aux personnes âgées, ASPA) | Elderly | ||

| Supplementary disability allowance (allocation supplémentaire d'invalidité, ASI) | Special case (disability) | ||

| Allowance of specific solidarity (allocation de solidarité spécifique, ASS) | Working-age | ||

| HR | Guaranteed minimum benefit (Zajamčena minimalna naknada) | bsa_hr | Working-age and elderly |

| HU | Benefit for persons in active age (aktív korúak ellátása) | bsa_hu | Working-age |

| Old-age allowance (Időskorúak járadéka) | Elderly | ||

| IE | Supplementary Welfare Allowance | bsa00_ie | Working-age and elderly |

| Jobseeker's Allowance | bunnc_ie | Working-age | |

| Disability Allowance | Special case (disability) | ||

| Blind Pension | Special case (disability) | ||

| Carer's Allowance | Special case (care) | ||

| Farm Assist | Special case (farmers) | ||

| Widow's, Widower's or Surviving Civil Partner's | Special case (widowhood) | ||

| State Pension | Elderly | ||

| IT | Guaranteed Minimum Income or Pension (Reddito o Pensione di Cittadinanza) | bsamm_it | Working-age and elderly |

| Social allowance (Assegno sociale) | Elderly | ||

| Guaranteed Minimum Pension (Pensione di Cittadinanza) | Elderly | ||

| LT | Cash social assistance (Piniginė socialinė parama) | bsa00_lt | Working-age and elderly |

| Social assistance pensions (Šalpos pensija) | Elderly and special case (disability) | ||

| LU | Social inclusion income (revenu d'inclusion sociale, Revis) | bsacm_lu | Working-age and elderly |

| LV | Guaranteed minimum income (GMI) benefit (Pabalsts garantētā minimālā ienākuma līmeņa nodrošināšanai) | bsamm_lv | Working-age and elderly |

| MT | Social assistance (Ghajnuna Socjali) | bsa_mt | Working-age |

| Unemployment Assistance (Gℏajnuna gℏal-Diżimpjieg) | bunncmt_mt | Working-age | |

| NL | Participation Act (Participatiewet) | bsagross_nl | Working-age and elderly |

| bsanet_nl | |||

| PL | Periodic Allowance (Zasiłek okresowy) | ben_sa_pl | Working-age and elderly |

| Permanent Allowance (Zasiłek Stały): | Elderly and special case (disability) | ||

| PT | Social integration minimum income (Rendimento social de inserção) | bsa00_pt | Working-age and elderly |

| Old-age social pension (pensão social de velhice) | Elderly | ||

| Widow(er)'s pension (pensão de viuvez) | Special case (widowhood) | ||