Inflation, Fiscal Policy, and Inequality: The Impact of the Post-Pandemic Price Surge and Fiscal Measures on European Households

This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the Eurosystem. The views expressed are those of the authors.

Abstract

Following the inflation surge in the aftermath of the pandemic crisis, Euro Area governments adopted a large array of fiscal measures to cushion its impact on households. The inflationary shock and related fiscal measures affected households differently depending on their country, their consumption patterns, and their position in the income distribution. This paper uncovers the aggregate and distributional impact of this inflationary shock, as well as the impact of the government measures aimed at supporting households and containing prices. The analysis is carried out for 2022 and includes Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece. Our work confirms that the purchasing power and welfare of low-income households was more severely affected than that of high-income households. Fiscal measures contributed significantly to closing this gap, though with country differences. However, most fiscal measures were not particularly targeted at low-income households, implying a low cost-effectiveness in protecting the poorest in some countries.

1 Introduction

In the aftermath of the pandemic crisis, a sudden and unexpected acceleration of prices, in particular of food and energy goods, hit the world economy. In the euro area, inflation rose from 2.6% in 2021 to 8.4% in 2022. Price growth is expected to decline toward the European Central Bank target of around 2% by 2025; however, by then, consumer prices are forecast to be almost 25% higher than in 2020. Governments adopted a large array of fiscal measures to cushion the impact of the inflationary shock on households and firms. In the euro area, these discretionary fiscal measures were estimated to represent around 2% of GDP, in both 2022 and 2023 (Bankowski et al., 2023). About half of this support was directed to contain price increases (“price measures”) and the other half to support households' income directly (“income measures”).

High inflation has a detrimental impact on the purchasing power and welfare of households, with lower income households being affected disproportionately. Low-income households consume a higher share of their income and, in the lowest decile, often more than their income. Besides, poorer households are often credit-constrained, and higher inflation immediately threatens their current consumption (Charalampakis et al., 2022). Furthermore, these households spend a large part of their consumption on basic goods and services, such as food and energy, which have experienced the largest price increases.

A key question in the academic and policy debate is therefore how unequal the impact of this inflationary shock across income groups was, as well as to what extent government measures were effective in mitigating adverse distributional effects. However, a comprehensive assessment of both income and price measures as well as of their relative efficacy is missing for most Eurozone countries. One of the biggest difficulties of this type of analysis is its complexity: government measures were numerous, diverse, and sometimes targeted at households according to complex eligibility criteria. Their simulation is therefore a challenging task that requires the combination of different data sources (on households' incomes and prices) and tools (to simulate both income and price measures in an integrated manner). Undertaking this analysis in a cross-country framework that allows meaningful comparisons adds a further layer of complexity.

In this paper, we aim to fill this gap by employing a comprehensive policy modeling approach based on microsimulation techniques to simulate both the heterogeneous impact of inflation across income groups (given their consumption shares and their consumption baskets) and the heterogeneous impact of income and price measures adopted during 2022 in selected Eurozone countries. Specifically, we use the microsimulation model of the European Union (EUROMOD), together with its extension to indirect taxation—the Indirect Tax Tool (ITT). In a nutshell, EUROMOD is a complex tax benefit calculator built on European survey data that allow us to simulate the impact of changes in gross income, direct taxes, social contributions, and benefits on household disposable income and, through its extension to indirect taxes, allows to account also for changes in consumer prices and consumption taxes.1

Our analysis focuses on Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, whose experience is studied individually, as well as aggregately, as a (GDP-weighted) proxy of the euro area.2 Using EUROMOD and the ITT, we simulate the inflation shock and the compensation measures introduced by governments to support household income and mitigate price increases. We can therefore assess the distributional impact of these measures on households' purchasing power and welfare and to what extent they were able to curb the increase in inequality caused by surging prices. We recur to the concept of compensating variation to measure households' welfare, measuring its variation as the monetary amount that would be needed to reach the initial level of utility the household enjoyed before the inflationary shock.

While there were several analyses of the effects on inequality of the great financial recession (e.g., Agnello & Sousa, 2014; Jestl & List, 2023; Savage et al., 2019) or of the COVID-19 crisis (e.g., Adermon et al., 2024; Blundell et al., 2020; Cantó et al., 2022), there is not a comparable body of research on the effects of the 2022 inflation. Yet, a growing number of contributions are recently investigating the impact of the inflationary shock in the EU (see, for instance, Menyhért, 2022; Sologon et al., 2022; Basso et al., 2023; Bonfattia & Giarda, 2023; Kuchler et al., 2023; Prati, 2023), as well as the mitigation effect of government measures in individual countries (Capéau et al., 2022; Curci et al., 2022; García-Miralles, 2023). To our knowledge, this paper is the first that assesses the cushioning effect of policy measures in a comparative and comprehensive way, that is, across euro area economies and considering both income and price measures, using the same modeling platform. Our cross-country analysis assesses key policy issues such as the distributional impact of inflation, the extent to which fiscal policy response sheltered households, and the relative ability of different policy measures to close the inequality gap opened by the price surge. Of the various channels through which inflation affects households (see for a recent discussion, Cardoso et al., 2022; Chafwehé et al., 2024), this work focuses on income and consumption, distinguishing between the effect on the purchasing power of income and on household welfare. Given that the latter accounts for consumption and saving patterns, it allows to better capture the disproportional effect of inflation on low-income households due to low-saving rates.

Our findings confirm that the welfare of lower income households was more severely affected by the 2022 inflation surge than that of high-income households. For the euro area, the impact of the price increases alone would have meant a drop in welfare of more than 13% for the lowest income households, 2.8 times higher than that of the highest income households. We find that this “welfare gap” or “inequality gap” was mainly driven by two factors. First, low-income households had a higher weight of energy-intensive goods in their consumption basket; hence, they generally faced higher effective rates of inflation. Second, and more importantly, low-income households suffered more from inflation due to their higher share of income spent on consumption, as can be seen in Online Figure A1. These households typically do not save a share of their income but often pile up debt to stabilize their real consumption (negative savings),3 but income underreporting may also play a role, especially in countries where the submerged economy is important or when social transfers are also reported as lower than they actually are (see, for instance, Bruckmeier et al., 2018).

Fiscal measures have significantly contributed to mitigating the loss in purchasing power and the rise in inequality, though with some differences across countries. Indeed, government measures—together with increases in market incomes—almost completely offset household welfare loss in France, Portugal, and to a large degree also in Italy. Significant differences in the exposure to inflation across households remain only in Spain and Germany. However, most fiscal measures were not particularly well targeted at low-income households, implying a relatively high fiscal burden. Indeed, around one-half of the 2022 government measures were directed toward containing the increase in prices. These measures, by their transversal nature, cannot easily be directed at households in need of support but benefit all consumers. Making use of income measures more targeted at the lowest income households could have closed the welfare gap at a far lower fiscal cost. For the euro area, the gap closed by the income measures was three times as large as that closed by the price measures, per euro spent. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of income-side measures also varied significantly across countries, which suggests that the policy debate should go beyond the discussion of price versus income measures and should focus on how to best design targeted measures.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the microsimulation model employed for the analysis, the fiscal measures simulated, the data used, and our framework for welfare analysis. Section 3 presents the results of the analysis. Section 4 concludes.

2 Methodology and Data

Our research question requires the use of microdata on income and consumption to explore the heterogeneous effects of inflation across households. It also requires a thorough and integrated modeling of tax and benefit systems to incorporate the impact of fiscal measures. Finally, we need detailed information on observed income growth and on policy changes in the recent period.

In this section, we present in detail the different tools involved in our analysis. Section 2.1 describes EUROMOD and its extension to indirect taxes. Section 2.2 describes the household-level microdata from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) and the Household Budget Survey (HBS) used by the model. Section 2.3 presents the government income and price measures that we modelled in each country. Finally, Section 2.4 develops our framework for welfare analysis.

2.1 EUROMOD and its Extension to Indirect Taxes

EUROMOD is a static microsimulation model, which contains detailed descriptions of the tax and benefit systems of all 27 EU member states.4 It uses representative data of the population of each country with information on different sources of income (gross earnings, pensions, social transfers), household composition and socioeconomic characteristics to simulate taxes, social insurance contributions, benefits, and, consequently, disposable income. As a result, EUROMOD allows studying the effects of changes in the tax and benefit system on the disposable income of individuals and households.5 Hence, it offers a particularly convenient setup to introduce the extraordinary income support measures implemented in 2022 by the different governments to cushion inflation across different countries.

To assess the impact of inflation and price measures, we use the newly developed extension of EUROMOD to indirect taxes.6 This allows for the simulation of indirect taxes, the introduction of price increases, and the modeling of price measures. The ITT uses household expenditure information for around 200 commodity categories from the harmonized Eurostat Household Budget Surveys (EU-HBSs). Starting from the household disposable income simulated by EUROMOD, the ITT applies the indirect taxation rules in place in each country (i.e., VAT, specific and ad valorem excises) to simulate “adjusted household disposable income,” that is, income after direct taxes, cash benefits, and consumption taxation. Consumption tax liabilities for households are therefore calculated based on their reported consumption, by applying the excise duties and the rates of VAT foreseen by the tax code of each country.

Using EUROMOD in the context of our analysis is convenient for two main reasons. First, it allows for cross-country comparable analysis, providing a comprehensive assessment of the impact of fiscal measures across countries. This overcomes the limitations of using different national microsimulation models, which often employ different methodologies, data sources, and assumptions. Second, with its ITT extension, it is the only cross-country microsimulation model covering both direct and indirect taxes as well as benefits, which is crucial for our analysis that requires simulating both income-side (e.g., increase in social benefits) and price-side (e.g., VAT cuts) measures.

EUROMOD is a static tax-benefit simulator that abstracts from behavioral responses to policy changes and shocks. Accordingly, our analysis implies no demand responses to the inflationary shock, and it assumes full pass-through of price measures from firms to households. We discuss the implications of the assumption on households' behaviour in Section 2.4.

2.2 Data

EUROMOD uses input data from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) provided by Eurostat.7 EU-SILC is a representative sample of the EU population. It provides a yearly cross-sectional survey of households on income, poverty, social exclusion, and living conditions that is standardized across all EU member states. Survey data are available for all EU member states, for a household sample ranging from 11,000 households in Germany to about 15,000 households in Greece and Spain, in 2020.

Because survey data are only available with a considerable time lag, they need to be adjusted to approximate household income in the years 2021 and 2022. In this paper, we used the EU-SILC 2020 wave (2019, for Germany, Italy, and France), which were the latest available at the time the analysis was performed.8 These data report income corresponding to the year 2019 (2018) and are, therefore, not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Given the time lag, gross income from labor, capital income, pensions, and other (nonsimulated) benefits needed to be adjusted to reflect income in the “base” year, that is, 2021, and in the “inflation-shock” year, that is, 2022. This entails updating relevant monetary variables based on information obtained from various data sources, an exercise that is denominated as “uprating” in the EUROMOD jargon.9

To study the distributional effects of price-side measures as well as of inflation itself, we additionally rely on the harmonized EU-HBSs from 2010.10 The expenditure patterns for the different categories of goods, and in particular for energy-related ones, in aggregate and distributional terms, seem to be relatively stable throughout the 2010–2020 period (see Figures A2 and A3 in the Online Appendix), which is reassuring about the goodness of using the 2010 wave to mimic actual consumption patterns. The HBS is an EU-wide survey that collects detailed data on households' expenditure on goods and services and is compiled by Eurostat every 5 years.11 These data, which are available for all EU member states, allow us to compute household-specific rates of inflation, consumption tax liabilities, and the impact of price-side measures (which often took the form of reduction consumption taxation rates).

2.3 Modeling Income and Price Measures

The discretionary policy response to the inflationary surge has been quite diverse across countries, both in terms of size and in terms of composition. Around half of the measures implemented by euro area governments in 2022 aimed at supporting household income while the other half was aimed at containing the increase of prices.

Overall, we simulated 56 fiscal measures, which cover nearly all income and price measures in the six euro area countries considered, as presented in Tables 1 and 2.12 These were identified as support measures whenever there was a clear announcement by the government that they were intended to mitigate the negative impacts of inflation on households' purchasing power.13 In a nutshell, income measures consisted mainly of cash transfers, classified under “Other social benefits other than in kind” in Table 1, which were to a greater or lesser extent targeted at lower income families or other vulnerable groups, such as pensioners, the disabled, and the unemployed. These were extraordinary measures in the form of either one-off payments or supplements to existing benefit schemes. Price measures consisted mainly of price caps, price subsidies, and discounts, as well as VAT reductions (on energy or food). Price measures directed to firms, such as subsidies, are not accounted for in this analysis. A detailed list of all measures simulated can be found in Online Appendix 2.14

| Type | Subtype | Germany | Greece | Spain | France | Italy | Portugal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Direct taxes | 2 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 3 |

| Social security contributions | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Old age pensions | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Unemployment benefits | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Social transfers in kind | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | |

| Other social benefits other than in kind | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 19 | |

| Total income measures | 7 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 28 | |

| Price | VAT | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Excise | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Price cap | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | 3 | |

| Reimbursement | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | |

| Discount/Subsidy | - | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 7 | |

| Social transfers in kind | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Total price measures | 3 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 28 | |

| Total | 10 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 56 | |

| Germany | Greece | Spain | France | Italy | Portugal | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of income measures simulated | 100% | 100% | 49% | 100% | 94% | 100% | 96% |

| Total income measures (billion euros) | 42 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 8.4 | 18.8 | 2.2 | 73.6 |

| Share of price measures simulated | 100% | 98.5% | 100% | 99% | 100% | 100% | 95% |

| Total price measures (billion euros) | 11.8 | 4.4 | 7.9 | 35.5 | 23.8 | 1 | 84.4 |

- Note: The extraordinary revaluation of pensions in France, amounting to around 4.9 billion euros, in 2022, is included in the income measures reported in this table. However, in the simulations implemented in the next sections, this measure was modeled as part of the nominal growth of incomes between 2021 and 2022. The share covered is calculated as a share of the sum of all measures estimated.

- A. The baseline scenario. This is the policy system at 2021 income, prices, and policies. It represents the basis against which the actual and the counterfactual scenarios are compared.

- B. The actual scenario. This is the policy system at 2022 prices and policies, including the income-side and price-side policy implemented by the government in response to the inflationary shock.

- C. The counterfactual scenario. This is the policy system at 2022 prices and policies but excluding the income-side and price-side policy implemented by the government in response to the inflationary shock. We simulate this scenario both with 2021 incomes and with 2022 incomes separately.

Comparing the growth of income and prices under (B-A) gives us household nominal income growth and effective inflation rates with government policies in place. A further comparison with respect to (C-A) allows us to isolate the effect of government measures.

Moreover, we break down nominal disposable household income, between 2021 and 2022, into (i) market income growth,15 (ii) the impact of compensation measures, and (iii) the effect of other income measures unrelated to the inflation surge (such as policy changes related to benefit updating). To isolate the policy effect from other changes in the income distribution, household disposable incomes under the actual and counterfactual system are assessed holding household characteristics and market incomes constant. Policy changes unrelated to inflation could be recovered by comparing scenarios (C-A) under 2021 incomes, whereas inflation-related policy changes could be obtained by comparing (B-A) with (C-A) also under 2021 incomes. Notice that, in practice, once income support measures were identified, all the remaining and discretionary policy changes simulated fall in the inflation-unrelated policy changes.16,17 Finally, the impact of market income growth is given by the change in (B-A) when calculated under 2022 and 2021 incomes.

2.4 Welfare Analysis

Equation (2) formalizes the concept of CV stated above. Namely, the monetary amount needed to attain, after the inflationary shock, the same level of utility attained before the inflationary shock. This is our money-metric measure of welfare variation.

To calculate the CV in Equation (2), we are required to make a specific assumption about the household's preferences (i.e., the utility function, u). Our static framework in EUROMOD and in the Indirect Tax Tool implying constant consumption quantities is consistent with a Leontief utility specification. Under this assumption on utility, to compensate for the inflationary shock, households must receive the amount of money needed to purchase the same bundle they were consuming before the shock (see Vandyck et al., 2021, for an application of the same approach to measure welfare impacts of broader macroeconomic shocks). This is equivalent to considering that households' consumption basket is composed by complementary goods, with a marginal rate of substitution of zero.

Equation (5) hence represents the change in our money-metric welfare measure under Leontief preferences. This corresponds to the monetary amount the household needs to buy the preinflationary shock consumption basket at the inflated prices—net of any income variation. Effectively, it provides a rationalization of our framework at constant consumption quantities.

We believe that the constant quantity assumption constitutes a reasonable approximation for the analysis of the 2022 inflationary shock on several grounds. First, the 2022 price shock was arguably unanticipated, taking consumers by surprise. In this context, it is likely that consumers had little margin to adjust their consumption plans. Second, the main drivers of inflation were mostly necessity goods such as energy and food whose elasticity of substitution is known to be small. Third, related studies (see Sologon et al., 2022), who estimated expenditure functions for EU countries to calculate the compensatory variation accounting for substitution effects, found these effects to be small.

3 Findings

The following section describes and discusses the simulation results obtained. Section 3.1 describes aggregate price and income developments and the effect that government measures had on inflation and disposable income growth. Section 3.2 considers the distributive impact of inflation and government measures by income groups for the Eurozone as a whole, whereas Section 3.3 investigates how this impact varies across the six economies in our analysis. Finally, Section 3.4 looks into inequality and the cost-effectiveness of the distinct types of government measures. Throughout the presentation of our findings, we refer to the “Euro Area” as the GDP-weighted average of the countries included in our analysis.

3.1 Inflation, Disposable Income Growth, and the Effects of Policy Measures

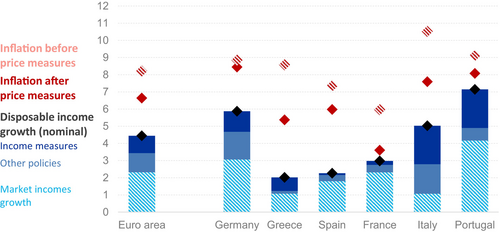

Government price measures significantly lowered consumer inflation in the euro area and—to varying degrees—in the individual countries,19 as reflected in Figure 1. Euro area consumer price inflation in 2022 would have been 1.6 percentage points higher without the government price measures, standing at 8.2% (inflation before policies) instead of 6.6% (consumer price inflation). Notably, variation across the euro area countries is significant. Differences in the exposure to the energy shock meant that—absent price measures—consumer price inflation would have ranged from 6% in France to 10.5% in Italy. In both these countries, as well as in Greece, the impact of price measures was the most significant reducing inflation by at least 2 percentage points. On the other hand, the impact of price measures was negligible in Germany and small in Portugal, given these two countries adopted a policy mix largely based on income measures.

Source: Own Calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

Furthermore, changes in nominal disposable income significantly added to household purchasing power in the euro area countries. We estimated that equivalized household disposable income20 increased by 4.4% in 2022, which can be broken down into a 2.3 percentage point increase in the nominal market incomes (salaries, wages, pensions, etc.), 1 percentage point from inflation-related measures on the income side, and about another one from policy changes in the tax and transfer system not related to inflation. Given low market income growth and a policy mix largely centered on price measures, Greece and Spain show relatively low increases in nominal disposable income of below 2.5%, while Germany, Italy, and Portugal are simulated to have had increases of more than 4%. In Italy, a very slow market income growth was compensated by the generosity of policy measures.

Despite government measures and rising disposable incomes, household purchasing power is simulated to have dropped significantly in 2022. For the euro area aggregate, the difference between the increase in equivalized household disposable incomes and the effective consumer prices increase (i.e., the difference between the stacked bar and the red diamond) amounts to 2.2 percentage points. Again, there are significant differences across euro area countries. Households faced the highest losses in Spain and Greece, where losses in purchasing power amounted to more than 3%. France, on the other hand, was characterized by low inflation, a small number of income measures and significant price measures, resulting in the smallest purchasing power loss among the six countries, at just 0.6%.

Simulated nominal disposable income growth and consumer inflation are broadly similar to the official statistical recordings. The average annual inflation rate in the euro area in 2022 amounted to 8.4%, which is broadly in line with the counterfactual consumer price increases simulated with EUROMOD excluding the government price measures.21 Similarly, nominal disposable income growth according to the EUROMOD simulations is similar to official government statistics, where these are available for 2022.22

3.2 The Distributional Impact of Inflation and Government Measures in the Euro Area

We now turn to assess the distributional effects of the inflationary shock and related fiscal policy response across income groups. We do so from two different perspectives: first, looking at their impact on real disposable income and second, focusing on household expenditure to measure the impact on welfare. To assess the impact on real disposable income, we compare changes in nominal disposable income and consumer inflation by income decile, providing a general overview of the effects of the shock and policy interventions on the purchasing power of households. Then, we jointly evaluate price and income changes by measuring the variation in expenditure—net of any income increase—needed for households to retain their level of welfare.

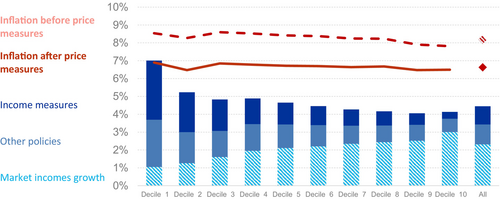

As shown in Figure 2, the variation in real disposable income is generally progressive for the Eurozone as a whole, with the richest households suffering the largest erosion of the purchasing power of their income (about 3%), whereas the poorest display an income growth that fully offsets inflation. This is the result of different forces driving income growth and inflation. On the inflation side, government price measures have significantly reduced inflation across the income spectrum and also reduced the inflation gap between poorer and richer households. Actual inflation—including government measures—was around 20% lower than in a counterfactual scenario in the absence of policy measures. While lower income households are more affected by energy and food inflation, they also profited relatively more from price measures. Thanks to price measures, the actual inflation rate across households is simulated to be widely equalized.

Source: Own calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

On the disposable income side, considering all sources of income growth—market income growth as well as government measures related and unrelated to inflation—household income grew by around 4 to 5% in the second to tenth income brackets. Disposable income growth in the lowest income bracket was significantly higher, at 7%. As expected, market income growth and income support measures are inversely related across the income spectrum. The contribution of income measures to household income gradually decreases from 3% in the first decile to 0.4% for the richest households. This is because eligibility for a large proportion of the income measures is bound to income thresholds and transfers are phased out as income increases. On the other hand, income from market activities often contributes less to the disposable income of poorer households who are more reliant on unemployment benefits or other social benefits.23 Finally, government income policies not explicitly linked to the inflation surge—such as increases in pensions and unemployment benefits—had a significantly larger impact in the lower deciles. Altogether, government measures closed the gap in disposable income growth across the household income spectrum and implied that—on average—the disposable income growth of the poorest households was slightly higher.

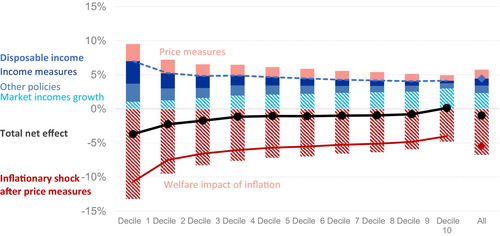

The picture of household welfare looks somewhat different. This can be observed in Figure 3 showing the effects of inflation, income growth, and government policies on households' welfare across income deciles. Negative bars show the impact of the inflationary shock on the decile-specific consumption basket, that is, the increase in household expenditure as a share of household disposable income, before considering compensating government policies on the price side. Positive bars show the impact of (i) market income growth, (ii) government measures unrelated to the inflationary shock, and (iii) the inflation compensation measures as a percentage of household disposable income in the baseline scenario. The total net effect is obtained by deducting the negative inflationary shock from the total positive impact of market income growth and all government measures, and it is represented by the black line.

Source: Own Calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Extension Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

A few aspects are worth noting. First, the welfare of all but the tenth (richest) decile decreased, even considering the impact of government compensation measures, with the bottom three deciles suffering the strongest welfare reduction. Second, government measures closed about half of the welfare gap of 8.4 percentage points between the lowest and highest income deciles created by the inflation surge. Considering all effects, a gap of 3.8 percentage points in welfare remains between the poorest and richest households. Third, richer households mainly benefited from strong increases in market incomes, while for lower income households, the inflation compensation measures on both the income and price sides did not fully offset the increase in consumer prices. Price measures were far less targeted at the poorer households compared with income measures.

It is important to emphasize the amplification of the distributional effect of the 2022 inflationary shock in welfare terms, where poorer households suffered greater losses due to inflation than richer households. Because disposable income and expenditure are generally not equal, the expenditure impact of a consumer price shock on disposable income can be larger or smaller than the inflation rate itself, as discussed in Section 2.4. The gap between the inflationary shock as expenditure variation and the inflation rate in Figure 4 is indicative of the share of income consumed in each decile, a pattern we show directly in Online Appendix Figure A1. In deciles 1 and 2, the increase in expenditure to afford the same consumption bundle exceeds the inflation rate, implying that consumption exceeds the household's disposable income (i.e., negative savings). As a result, the impact of the increase in expenditure relative to disposable income in the first decile is larger than the effective inflation rate. The opposite holds true for deciles 3–10, where households earn more than they consume, and savings are therefore positive, dampening the inflation impact.

Source: Own Calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

3.3 The Distributional Impact of Inflation and Government Measures for the Euro Area Countries

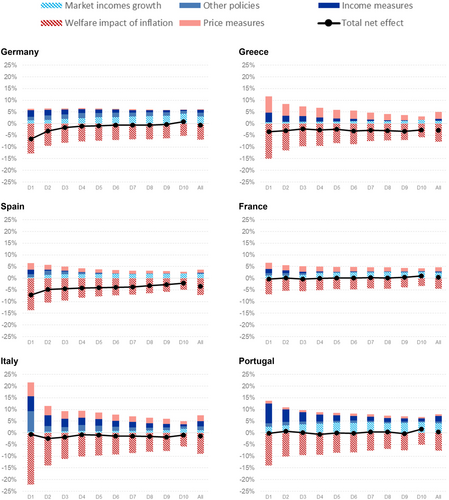

Now we take a closer look at the inflationary shock and government responses across countries. We will focus on three main types of difference: (i) the size and distribution of the inflationary shock and the government response, (ii) the use of income versus price measures, and (iii) the distributional outcome after considering market income growth and the government response. Results are presented in Figure 5.

Source: Own Calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

First, governments seem to have geared their policies toward compensating for the welfare of households across the income distribution. France and Italy serve as illustrative examples, where the 2022 inflationary shock plays out differently in terms of its impact on the distribution of disposable household income. Poor households were severely hit by the inflationary shock in Italy, which reduced their welfare by almost 25%. By contrast, the year-on-year loss in welfare in France was much smaller, ranging between 7% in the lowest income decile and 3% in the highest income decile. However, in both countries, the final welfare loss was almost completely equalized between the top and bottom deciles, mainly on account of fiscal measures. Italy implemented both price and income measures that strongly supported households and helped to offset the loss in welfare by around 12 percentage points in the lowest decile and 2.2 percentage points in the highest decile, even after taking into account income growth and other measures. In France, price and income measures reduced the loss in welfare by around 4.5 percentage points in the lowest decile and 1.2 percentage points in the highest decile.

Second, while some countries placed a strong focus on containing price increases, others took more measures to support households via transfer payments. Here, Greece and Portugal serve as two almost polar cases. Greece resorted mainly to price measures, which compensated for the purchasing power loss in the first income decile, while income measures played a much smaller role. By contrast, price measures in Portugal only compensated for about 1 percentage point of the poorest households' welfare losses, while income measures played a much larger role. It is worth noting that these income measures in Portugal faded away toward the higher income deciles. By contrast, price measures were more evenly spread throughout the deciles both in Greece and in Portugal. In France, too, price measures played a bigger role than income measures.24

Third, the distributional impact of the inflationary shock was broadly offset in all countries, except Germany and Spain. While the a priori distributional impact of inflation was quite different across countries, government measures have largely closed the gap in welfare loss across the distribution in France, Italy, Portugal, and Greece. In France, Italy, and Portugal, the negative impact of inflation on welfare was almost fully offset. Italy, Portugal, and Greece experienced strong redistribution through fiscal measures. In the case of France, the inflation shock was smaller, requiring a smaller effort to compensate for unequal price increases. In Greece, a welfare loss of around 3% remains. In Germany, inflation was mostly offset by nominal wage growth, from which higher income households gained more in terms of changes in disposable income but not as much through fiscal policies. Similarly, the amount of redistribution attained with the fiscal measures implemented in Spain was limited. In Germany and Spain in particular, lower income households lost a higher share of their disposable income. A significant gap of around 7.5% and 5.1% remains between the first and tenth deciles in Germany and Spain, respectively, while all households experienced a significant loss from the inflationary shock, ranging from 3 to 7%.

3.4 Impacts on Inequality and the Fiscal Cost of the Inflation Compensation Measures

In this section, we evaluate how the inflation compensation measures contributed to closing the inequality gap created by the inflationary shock. As we have seen, lower income households suffered relatively higher losses of welfare vis-à-vis higher income ones. Although behind the political decision to implement inflation support measures there might be other motives besides closing this welfare gap, it is important to analyze how much of the limited public resources were targeted at the households with less ability to shield their welfare from the inflationary shock.

By examining the change in the S80/S20 ratio for the euro area, we can see that compensation measures have made a significant contribution to limiting the inequality—increasing pressures created by the 2022 inflationary shock in the euro area. Figure 6 breaks down changes in the quintile share ratio (S80/S20) calculated based on the welfare measure introduced in Section 3.2. Inflation has—together with the uneven effects of growth in market income—increased inequality in the euro area. The S80/S20 ratio increased by around 7%25 on account of inflation and by around 2% on account of market income growth. However, government inflation compensation measures on the income and price side have reduced the S80/S20 ratio by around 3%. Other policy changes on the income side, for example, adjustments to income tax brackets, also helped to reduce inequality.

Source: Own Calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

Compensation measures decreased welfare inequality across the six euro area countries, although the impact was stronger in some countries than in others, as observed in Table 3. More progressive profiles of the measures resulted in higher inequality reductions, such as in the case of Greece, Italy, and Portugal. Given that income measures are typically more targeted at lower income households, they are generally more effective at reducing inequality than price measures.

| Inequality Measure | Germany | Greece | Spain | France | Italy | Portugal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in S80/S20 ratio due to inflation-related government policies (in points) | −0.10 | −0.36 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.32 | −0.27 |

| Contribution from income measures | 83% | 45% | 45% | 57% | 58% | 95% |

| Contribution from price measures | 17% | 55% | 55% | 43% | 42% | 5% |

- Note: Individuals ordered across deciles according to their equivalized disposable income in the baseline scenario (2021).

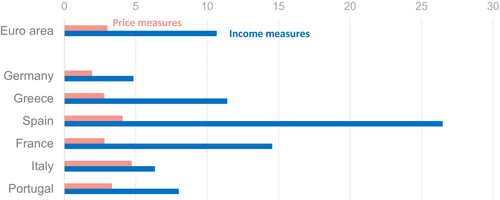

However, most of the price measures adopted by governments were not targeted at lower income households. Untargeted price measures dampen price increases for all consumers and incur high fiscal costs compared with income measures. To dig into this aspect, in Figure 7, we report a cost–benefit metric of income and price measures across the six countries. This represents the increase in welfare for the bottom 20% divided by the fiscal cost by type of measure as a percentage of GDP. There we can appreciate how governments could have reduced the negative impact of the inflation surge on inequality at a lower fiscal cost by targeting income measures to vulnerable households.26 Indeed, price measures are inefficient in all countries and to a similar degree: For every additional 1% of GDP in expenditure, the welfare of the first quintile is raised by less than 5%. In contrast, income measures can be targeted much more effectively, with the first quintile in the Eurozone gaining over 10% for a similar increase in spending. Moreover, their effectiveness has varied significantly across countries, with the first decile gaining beyond 25% in Spain through income measures.

Source: Own Calculations Based on EUROMOD and ITT Simulations, Using EU-SILC and HBS Data.

Finally, it should be noted that price measures are also subject to imperfect pass-through of government subsidies or tax cuts to prices by firms, which can reduce the efficiency of these policies. In some countries, for example Germany, the use of untargeted price measures was justified on the grounds of lacking the information needed for effective targeting of fiscal support (see Arregui et al., 2022). This advocates for regulation reforms and public investment to build fit-for-purpose modeling tools that allow targeting social interventions also beyond crisis situations.

4 Conclusions

This paper assesses the distributional impact of the 2022 inflation surge in the euro area and the inflation compensation measures implemented by euro area governments. It applies the EU microsimulation model EUROMOD and its indirect tax tool to assess how inflation as well as income and price measures to support households have affected their purchasing power and welfare across the income distribution. Results are presented for a proxy of the euro area, as well as individually for Germany, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal. The paper shows that the inflationary shock had a more detrimental impact on lower income than on higher income households. At the same time, and even though government measures were not strongly targeted at lower income households, policy interventions made a significant contribution to reducing the welfare loss on account of the inflation surge.

Our analysis underscores a few key policy messages. First, differences in consumption patterns among richer and poorer households often meant that the latter suffered higher effective rates of inflation in 2022. However, the disproportionate impact of inflation on poorer households' welfare was mainly attributable to their higher consumption shares of income. High consumption shares implied that the monetary amount that poorer households would have needed to sustain preinflation consumption often exceeded their actual income, resulting in large welfare losses. Our analysis therefore stresses the importance of accounting for saving patterns when assessing the impact of inflation on households. Second, the use of untargeted measures was largely cost-ineffective. Although other motives besides closing the welfare gap opened by inflation may concur to the design of public intervention—namely keeping the “social contract” and containing inflation—targeting public policies to the ones less able to shield from inflation is important because public resources are scarce. For the euro area, the reduction in the inequality gap achieved by income measures was three times as large as that achieved through price measures. Third, while price measures were similarly inefficient across countries, the cost-effectiveness of income-side measures varied dramatically. Abstracting from other public policy objectives and focusing on the effective and efficient use of public resources, this suggests that the policy debate should move beyond discussing price versus income measures and focus more on how best to design targeted measures and the information needed to enhance targeting.

The limitations of our analysis relate mainly to the static nature of the exercise and the focus on the household sector. Because EUROMOD is a static tax-benefit simulator, it does not account for households' reactions to changes in prices, nor firms' pass-through responses to any increase in production cost or government subsidy, assumed in the analysis as a full pass-through. To understand the full macroeconomic implications of government measures to compensate for high inflation, a general equilibrium model needs to be employed. Moreover, the analysis is limited to compensation measures made directly available to households. Many of the measures taken by governments were, however, directed at firms. These measures were sizable and also affected households, albeit indirectly, but are not part of this analysis.

Finally, it should be reminded that our work focuses on the impact of inflation on the consumption and income of households, disregarding the impact it had on households via their wealth and its composition. In fact, income, consumption, and wealth are the main determinants of households' well-being. From a joint income, consumption, and wealth micro dataset, Balestra and Oehler (2023) find that income and wealth are positively correlated, especially at the tails of the distribution. This may amplify even more our results regarding the inequality gap created by inflation. Besides, the introduction of the wealth channel would allow an even more comprehensive analysis of the policy response to the inflationary surge, with the possibility of jointly studying fiscal and monetary policies' impact. These are important avenues for future research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the ESCB Working Group on Public Finance and its Chairperson, John Caruana, for comments and support. We are also deeply indebted to Salvador Barrios (European Commission Joint Research Centre) for an extensive review of this work, his advice, and guidance. Comments from Philipp Rother, Diego Rodriguez Palenzuela, and three anonymous referees are also gratefully acknowledged. Special thanks go to Jan Kuckuck (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Niamh Dunne (Banque de France) for providing their expertise on the German and French fiscal measures, and to Silvia Navarro Berdeal (European Commission Joint Research Centre) for her help with the French updates of the EUROMOD tax and benefit systems for 2022.

References

- 1 The microdata used by EUROMOD and the ITT extension are the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) and the Household Budget Survey (HBS).

- 2 The six countries considered cover about 80% of the euro area population and more than three-quarters of the euro area in terms of GDP in 2022. They therefore provide a good proxy for the euro area aggregate, while offering a significant degree of variation in terms of demographics and fiscal policies. Nevertheless, a richer picture might be painted if more countries were added to the analysis, as their welfare systems and their policy responses to the cost-of-living crisis might differ even more. We see this as an interesting venue for future research.

- 3 In Household Budget Survey (HBS) data, households in the bottom two deciles often display negative savings, indicating that it is likely that poorer household rely on credit to finance consumption.

- 4 Information on EUROMOD: https://euromod-web.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ and Sutherland and Figari (2013).

- 5 In this analysis, we used EUROMOD version I4.109+.

- 6 In this analysis, we used the Indirect Tax Tool version 4.

- 7 For more details on the EU-SILC, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions.

- 8 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU-SILC 2020 data may have experienced reduced sample sizes in certain countries, which could affect the representativeness of the results.

- 9 EUROMOD includes uprating factors for all years simulated. The data are typically taken from Eurostat, provided by the statistical offices of the member states, government authorities, or national central banks. The exact uprating process differs depending on data availability and the institutional frameworks of each country. The Joint Research Centre publishes annual country reports, which describe in more detail the uprating exercise, policy changes, and the institutional setup of each EU country, in EUROMOD country reports. See Table A1 in Online Appendix for details on the uprating exercise for wages and earnings performed for this analysis. Note that similarly, nonsimulated benefits have also been uprated according to their respective social security rules in the context of this exercise, unless stated otherwise.

- 10 At the time this analysis was performed, the consolidation of the EU-SILC and HBS microdata was only available for the 2010 wave of the HBS.

- 11 For more details on the HBS, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/household-budget-survey.

- 12 All the French measures, except the incentives available for purchasing low emission vehicles, were simulated. All Greek measures targeting households were covered, except for some minor data-intensive subsidies. In Italy, all measures were modeled except minor subsides for public transportation and subsidies to workers in specific sectors (e.g., entertainment and sport industry). In the case of Spain, all price measures are modeled, while only about half of the income measures are modeled (which, however, are relatively small relative to the price measures).

- 13 Many support measures were announced as a “package” or group of measures which were especially aimed at supporting incomes and prices during the inflation surge. For instance, in Portugal, the income support measures were announced as included in a package called “Families First” (“Famílias Primeiro”), and their aim was clearly stated at the time of their announcement and approval.

- 14 A comparison of the fiscal cost of measures according to EUROMOD simulation and official government estimates is also provided in Online Appendix 2. In most cases, EUROMOD and government estimates are similar. Divergences may be on account of several factors, namely limited survey information for simulating eligibility conditions and partial information to construct counterfactual scenarios (most notably in the case of price cap measures).

- 15 Because household-level incomes are not available for 2022, this effect reflects our uprating assumptions between 2021 and 2022.

- 16 Some examples of inflation-unrelated policies are discretionary changes to the personal income tax brackets or to the rules and amounts of the child benefit, which were implemented progressively by governments across several years, according to the government legislative program.

- 17 In the case of a preexisting mechanism of indexing simulated benefits, fully or partially, to inflation, its impact on disposable income will appear together with the impact of the other discretionary policies unrelated to inflation, unless stated otherwise.

- 18 In our simplified framework, we do not model household intertemporal consumption and saving behavior. We rather focus on expenditure allocation among goods at a given point of time to study the welfare impact of inflation in the presence of heterogenous consumption. We, nonetheless, allow for exogenous saving/dissaving behaviour. This is important to measure the burden of additional consumption expenditure (over income) caused by inflation as discussed immediately below.

- 19 Recall that the euro area aggregate is approximated by the GDP-weighted sum of Germany, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal.

- 20 Equivalized disposable income is computed by dividing the household's disposable income by its size on the modified equivalence scale produced by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which assigns a weight of 1 to the first adult of the household and a weight of 0.5 (0.3) to each additional household member over (under) the age of 14.

- 21 Eurostat's general methodological advice is that the subsidized price is recorded in the consumer price index if the subsidy affects the quantity of the specific product/service that will be consumed in the specific reference month. However, detailed information on which measures were included by national statistical agencies is not available. Assuming that all the price measures were reflected in the official HICP, then it could be more appropriate to compare the HICP with simulated “actual” inflation. However, given that for some countries the simulated “counterfactual” inflation (without price measures) is closer to the evolution of the HICP, this may point to the fact that some national statistical agencies have not included price measures in the official HICP measure. Other sources of discrepancies between the official HICP number published by Eurostat and the “actual” simulated inflation rate might result from differences in the underlying consumption basket (recall that our simulation relies on data from the 2010 wave of the HBS) and from the fact that our simulation only considers goods consumed by households. Goods consumed by, for example, small firms are not included in the calculation of the simulated inflation rate. Moreover, in official statistics, items weighting in HICP are not only exclusively based on HBS data but also on National Accounts aggregates.

- 22 See Table A2 in the Online Appendix for further details on the validation of simulated disposable income growth against official statistics.

- 23 Also, increases in nominal earnings lead to the so-called bracket creep orfiscal drag, as higher tax rates apply if tax brackets are not adjusted (see Immervoll, 2005 or Paulus et al., 2020). The magnitude of the bracket creep effect depends on the difference between an individual's effective marginal and average tax rates. Households in the lower half of the income distribution face particularly strong tax progression, with low effective average tax rates but often very high effective marginal tax rates due to the phasing out of transfers.

- 24 Recall that in the case of France, the extraordinary revaluation of pensions is included in the nominal income growth category and not in the set of income support measures.

- 25 Note that the quintile share ratio (S80/S20), whose value in 2021 is 4.15, increases by 0.28 points on account of inflation, which corresponds to about 7%.

- 26 We validated the simulated fiscal cost of the measures against government estimates. EUROMOD estimates are, in general, close to and, in many cases, practically equivalent to government projections (see Figure A4 in the Online Appendix).