Increased risk of acute coronary syndrome in patients with bronchiectasis: A population-based cohort study

ABSTRACT

Background and objective

There are few studies on the relationship between bronchiectasis and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). We conducted a population-based cohort study to assess whether bronchiectasis was associated with an increased risk of ACS.

Methods

We identified 3521 patients diagnosed with bronchiectasis between 2000 and 2010 (bronchiectasis cohort) and frequency matched them with 14 084 randomly selected people without bronchiectasis from the general population (comparison cohort) according to sex, age and index year using the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database. Both cohorts were followed until the end of 2010 to determine the ACS incidence. Hazard ratios of ACS were measured.

Results

Based on 17 340 person-years for bronchiectasis patients and 73 639 person-years for individuals without bronchiectasis, the overall ACS risk was 40% higher in the bronchiectasis cohort (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 1.40; 95% CI: 1.20–1.62). Compared with those in the comparison cohort with one respiratory infection-related emergency room (ER) visit per year, the ACS risk was 5.46-fold greater in bronchiectasis patients with three or more ER visits per year (adjusted HR = 5.46, 95% CI: 4.29–6.96). Patients with bronchiectasis and three or more respiratory infection-related hospitalizations per year had an 8.15-fold higher ACS risk (adjusted HR = 8.15, 95% CI: 6.27–10.61).

Conclusion

Bronchiectasis patients, particularly those experiencing frequent exacerbations with three or more ER visits and consequent hospitalization per year, are at an increased ACS risk.

Abbreviations

-

- ACS

-

- acute coronary syndrome

-

- CHD

-

- coronary heart disease

-

- ER

-

- emergency room

-

- HR

-

- hazard ratio

-

- ICD-9-CM

-

- International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

-

- LHID

-

- Longitudinal Health Insurance Database

-

- NHI

-

- National Health Insurance

-

- NHIA

-

- National Health Insurance Administration

-

- NTM

-

- non-tuberculosis mycobacterium

-

- PCD

-

- primary ciliary dyskinesia

INTRODUCTION

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a group of disorders, including unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction (ST and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarctions), resulting from a sudden occlusion of blood flow in the coronary arteries. ACS- and sudden cardiac-related deaths are substantially increasing despite the decline in coronary heart disease (CHD)-related deaths because of advances in multidisciplinary CHD management.1, 2 Hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus are well-known for causing atherosclerosis that subsequently leads to CHD.3 Although these traditional risk factors account for approximately 88% of the population attributable risk of ACS, infection and chronic inflammatory disorders are also associated with increased ACS.4-7

Bronchiectasis is a lung disease characterized by an abnormal and irreversible dilatation of the bronchial tree caused by recurrent airway infection and inflammation.8 Currently, bronchiectasis can be easily diagnosed using high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) and is increasingly being reported worldwide.9-11 Patients with bronchiectasis have impaired mucociliary clearance and secretion accumulation, which may cause severe pulmonary infection and loss of pulmonary function, resulting in chronic morbidity and premature mortality.12-15

Many researchers have focused on the treatment outcomes for bronchiectasis.16-19 Studies have reported that patients with bronchiectasis had increased arterial stiffness and increased inflammation, which may increase risk of cardiovascular disease.20 However, studies investigating the relationship between bronchiectasis and ACS are limited. Navaratnam et al. indicated that the risk of CHD was 1.44-fold higher in patients with bronchiectasis than in those without bronchiectasis from 625 general practices in the UK.21 Therefore, we investigated the incidence and risk of ACS among patients with bronchiectasis in an Asian population.

METHODS

Data source

The National Health Insurance (NHI) programme was launched in Taiwan. Taiwan has abundant medical resources and convenient transportation, and thus people in Taiwan can easily visit a clinic or hospital and incur only low medical expenditure. According to the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, more than 99.5% of residents and more than 97% of healthcare institutions in Taiwan are part of the NHI programme (http://www.nhi.gov.tw/english/index.aspx). The Taiwan National Health Research Institutes established the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID), which contains the claims data of outpatient, inpatient, emergency and dental care, as well as prescription drugs. The NHIA encrypted the patient identities in the LHID before it was released for public use and research. We used the LHID2000, comprising data of 1 million randomly selected beneficiaries of the NHI programme in 2000. No statistically significant differences were observed in the distribution for age, sex and health care costs between the LHID2000 and NHI beneficiaries (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/Data_Subsets.html#S3). This database has been used reliably in our previous studies.22, 23 Patient diagnoses in the LHID2000 are based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. This cohort study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of China Medical University Hospital (CTU103-1/CMUH-REC-103-REC1-088).

Study patients

This study was a retrospective population-based cohort study. We identified 7156 patients diagnosed with bronchiectasis (ICD-9-CM code 494; for more than two times at health care institutions) from 2000 to 2010. Among the 7156 patients with bronchiectasis diagnosis, 3521 patients received further HRCT diagnosis to constitute the bronchiectasis cohort. The first bronchiectasis diagnosis date was defined as the entry date. Furthermore, we excluded patients below 18 years and above 90 years; those with incomplete information regarding sex or date of birth; and those diagnosed with bronchiectasis and ACS before the index date. In addition, we randomly selected 14 084 people without diagnosis of bronchiectasis from the general population and frequency matched them according to sex, age and entry year in a 4:1 ratio, thus forming the comparison cohort. The exclusion criteria for the comparison cohort were identical to those of the bronchiectasis cohort.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome was an ACS event (ICD-9-CM codes 410 indicating acute myocardial infarction and 411.1 indicating unstable angina). In Taiwan, the physicians made the diagnosis of ACS based on clinical symptoms, history, serial examinations of electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes, cardiac echo and cardiac catheterization if available. We determined the follow-up person-years by calculating the interval from the entry date to the date on which any of the following events first occurred: ACS diagnosis, withdrawal from the NHI programme, death or December 31, 2010.

Covariates

Age was stratified into ≤34 years, 35–49 years, 50–64 years, 65–74 years and ≥75 years. The baseline comorbidities were hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430–438), coronary heart disease (ICD-9-CM code 428), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, ICD-9-CM codes 491, 492 and 496), primary ciliary dyskinesia (ICD-9-CM code 759.3), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ICD-9-CM code 518.6) and non-tuberculosis mycobacterium (NTM, ICD-9-CM code 031). Furthermore, we stratified the study participants by the annual instances of respiratory infection-related emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalization to evaluate their effect on the risk of ACS.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean age of patients in both cohorts were compared and tested using the Student t-test, and the distribution of demographics and comorbidities in both cohorts were measured and tested using the chi-square test, The overall age-, sex- and comorbidity-specific ACS incidence for both cohorts were evaluated. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were employed to measure and compare the crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI) of ACS in the cohorts.

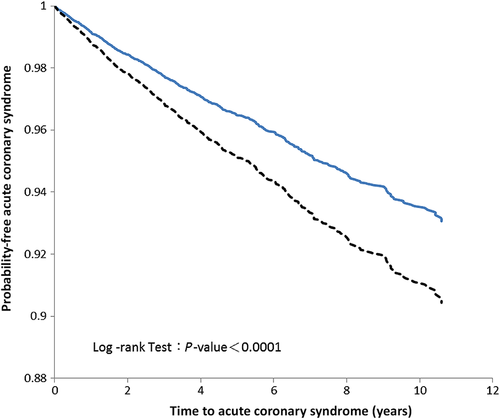

The Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test were used for assessing the differences in the ACS-free probability in both cohorts. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and comorbidities in both cohorts

Figure 1 illustrates the categorization of the study participants. The current study included a total of 3521 patients with bronchiectasis and 14 084 comparison patients. Both cohorts exhibited similar sex and age distributions because of frequency matching. The mean age (±SD) was the same (63.63 ± 14.71 years) in both cohorts. The prevalence of stroke, CHD, COPD and NTM was higher in the bronchiectasis cohort than in the comparison cohort (27.2% vs 20.4%, 31.2% vs 23.3%, 65.1% vs 21.3% and1.5% vs 0%, respectively; Table 1).

| Variable | Bronchiectasis | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| N = 14 084 | N = 3521 | ||

| Sex | n (%) | n (%) | 0.946 |

| Female | 7055 (50.1) | 1766 (50.2) | |

| Male | 7029 (49.9) | 1755 (49.8) | |

| Age, mean (SD)† | 63.63 (14.71) | 63.63 (14.71) | |

| Age stratification | 1.000 | ||

| ≤34 | 548 (3.9) | 137 (3.9) | |

| 35–49 | 1949 (13.8) | 490 (13.9) | |

| 50–64 | 4151 (29.5) | 1035 (29.4) | |

| 65–74 | 3596 (25.5) | 899 (25.5) | |

| 75+ | 3840 (27.3) | 960 (27.3) | |

| Comorbidity‡ | |||

| Hypertension | 7269 (51.6) | 1913 (54.3) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 3652 (25.9) | 956 (27.2) | 0.140 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 4193 (29.8) | 1054 (29.9) | 0.850 |

| Stroke | 2876 (20.4) | 957 (27.2) | <0.001 |

| CHD | 3288 (23.3) | 1097 (31.2) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 2995 (21.3) | 2292 (65.1) | <0.001 |

| PCD | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| ABPA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| NTM | 4 (0.0) | 52 (1.5) | <0.001 |

- † Student t-test.

- ‡ Chi-square test.

- ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CHD, coronary heart disease; NTM, non-tuberculosis mycobacterium; PCD, primary ciliary dyskinesia.

ACS incidence and hazard ratio stratified by sex, age and comorbidities

The overall ACS incidence was higher in the bronchiectasis cohort than in the comparison cohort (13.49 vs 9.07 per 1000 person-years). After adjustment for sex, age and comorbidities, patients with bronchiectasis had a 1.40-fold higher risk of ACS than those without bronchiectasis (95% CI: 1.20–1.62). The ACS incidence was higher in men than in women in both cohorts. After we controlled potential covariates, the risk of ACS was a 1.31-fold risk higher in men than in women. The ACS incidence increased with age in both cohorts. After adjustment for covariates, the risk of ACS was the highest in adults aged 75 years and above (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 7.57, 95% CI: 3.35–17.13), followed by adults aged 65–74 years (adjusted HR = 6.02, 95% CI: 2.66–13.61) and adults aged 50–64 years (adjusted HR = 3.34, 95% CI: 1.47–7.57) compared with that in adults aged 34 years and below. The risk of ACS was significantly higher in patients with comorbidities than in those without comorbidities (adjusted HR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.56–2.55; Table 2).

| Bronchiectasis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| Variables | Event | PY | Rate† | Event | PY | Rate† | Crude HR‡(95% CI) | Adjusted HR§(95% CI) |

| All | 668 | 73 639 | 9.07 | 234 | 17 340 | 13.49 | 1.48 (1.27–1.72)*** | 1.40 (1.20–1.62)*** |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 281 | 37 907 | 7.41 | 92 | 9070 | 10.14 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Male | 387 | 35 731 | 10.83 | 142 | 8270 | 17.17 | 1.50 (1.32–1.72)*** | 1.31 (1.14–1.50)*** |

| Stratified age | ||||||||

| ≤34 | 1 | 3122 | 0.32 | 5 | 771 | 6.49 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 35–49 | 14 | 12 323 | 1.14 | 10 | 3025 | 3.31 | 1.02 (0.42–2.49) | 0.87 (0.36–2.14) |

| 50–64 | 146 | 22 950 | 6.36 | 51 | 5469 | 9.33 | 4.47 (1.98–10.07)*** | 3.34 (1.47–7.57)*** |

| 65–74 | 252 | 19 592 | 12.86 | 79 | 4533 | 17.43 | 8.82 (3.93–19.77)*** | 6.02 (2.66–13.61)*** |

| 75 and above | 255 | 15 652 | 16.29 | 89 | 3542 | 25.13 | 11.28 (5.03–25.29)*** | 7.57 (3.35–17.13)*** |

| Comorbidity¶ | ||||||||

| No | 68 | 19 787 | 3.44 | 7 | 1567 | 4.47 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 600 | 53 852 | 11.14 | 277 | 15 773 | 17.56 | 3.44 (2.72–4.36)*** | 1.99 (1.56–2.55)*** |

- *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

- † Rate and incidence rate per 1000 person-years.

- ‡ Crude and relative HR.

- § Multivariable analysis including age, sex and comorbidities.

- ¶ Only to have one of the comorbidities: hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stroke, CHD, COPD and NTM.

- ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NTM, non-tuberculosis mycobacterium; PY, person-years.

ACS risk in joint effect of bronchiectasis and comorbidity

Compared with non-bronchiectasis patients without comorbidity, the bronchiectasis patients without comorbidity exhibited a higher risk of subsequent ACS but did not reach statistical significance. The risk of ACS was higher in bronchiectasis patients with comorbidities than in those non-bronchiectasis patients without comorbidities (adjusted HR = 2.82, 95% CI: 2.15–3.72; Table 3).

| Variables | ACS | Adjusted HR†(95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchiectasis | Comorbidity‡ | N | n | |

| No | No | 4391 | 68 | 1 (Reference) |

| No | Yes | 9693 | 600 | 2.04 (1.58–2.63)*** |

| Yes | No | 435 | 7 | 1.77 (0.81–3.85) |

| Yes | Yes | 3086 | 227 | 2.82 (2.15–3.72)*** |

- *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

- † Adjusted for age and sex.

- ‡ Only to have one of the comorbidities: hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stroke, CHD, COPD and NTM.

- ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CHD, coronary heart disease; HR, hazard ratio; NTM, non-tuberculosis mycobacterium.

ACS risk and annual instances of respiratory infection-related ER visits and hospitalization

Compared with the comparison cohort comprising patients with <1 instance of ER visit in a year, the risk of ACS was substantially increased in patients with bronchiectasis ≥3 instances of respiratory infection-related ER visits per year (adjusted HR = 5.46, 95% CI: 4.29–6.96). The patients with bronchiectasis who experienced ≥3 instances of respiratory infection-related hospitalization per year exhibited a 8.15-fold higher risk of ACS development than did the comparison cohort hospitalized <1 instance per year (adjusted HR = 8.15, 95% CI: 6.27–10. 61; Table 4).

| ACS | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | Crude | Adjusted† | |

| Non-bronchiectasis | 244/7492 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Bronchiectasis | |||

| Annual number of emergency | |||

| <3 | 559/9452 | 1.29 (1.11–1.50)** | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) |

| ≥3 | 99/661 | 9.06 (7.16–11.46)*** | 5.46 (4.29–6.96)*** |

| Bronchiectasis | 224/9022 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Annual number of hospitalization | |||

| <3 | 595/7929 | 2.33 (2.00–2.72)*** | 1.60 (1.36–1.87)*** |

| ≥3 | 83/654 | 13.76 (10.65–17.77)*** | 8.15 (6.27–10.61)*** |

- *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

- † Multivariable analysis including age, sex and comorbidities.

- ACS, acute coronary syndrome; HR, hazard ratio.

ACS-free probability during follow-up periods

The cumulative ACS probability was significantly higher in the bronchiectasis cohort than in the comparison cohort (log-rank test, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2).

) or without (solid line,

) or without (solid line,  ) bronchiectasis disorders.

) bronchiectasis disorders.DISCUSSION

Our population-based cohort study in an Asian population showed that the risk of ACS was 40% higher in the bronchiectasis cohort than in the comparison cohort after adjustment for sex, age and comorbidities. This finding is consistent with that by Navaratnam et al., in which the Clinical Practice Research Database in the UK was used for analysis.21

The biological mechanism of bronchiectasis contributing to an increased risk of ACS remains unclear. Bronchiectasis is a chronic respiratory disease with irreversible airway dilatation and chronic inflammation, recurrent bacterial infection and bronchial wall destruction.23, 24 Coronary atherosclerosis is essential for ACS pathogenesis, and inflammation plays a pivotal role in the atherosclerotic process.25 Inflammatory cytokines involved in the atherosclerotic process modulate the development and destabilization of arterial plaques.26, 27 Van Eeden et al. proposed that lung inflammation activates systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, leading to atherosclerosis and plaque disruption.28

A number of epidemiological studies have reported that infectious agents, namely, Streptococcus pneumoniae,29 Mycobacterium tuberculosis,4 Leptospira sp.,5 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae,30 are associated with an increased risk of ACS. Infection and inflammation may cause thrombotic responses by upregulating procoagulants, downregulating anticoagulants and suppressing fibrinolysis, all of which lead to a hypercoagulable state and progress to vascular obstruction.31 Bronchiectasis is widely associated with respiratory infections.32 Patients with bronchiectasis who experienced >3 instances of respiratory infection-related ER visits and hospitalization per year exhibited a considerable effect on the risk of subsequent ACS (Table 4).

Recent studies reported macrolides use for 6 to 12 months in patients with bronchiectasis may reduce exacerbation rates.33, 34 However, no patients received long-term use of macrolides in our study patients. A recent meta-analysis reported use of macrolides is related to cardiovascular death and ventricular tachyarrhythmia.35 We traced prescription duration of macrolides before the end of follow-up for each study participants. We only found 60 participants received less than 7-day macrolides and 35 participants received 7–14 days of macrolides. No statistical significance was present between macrolides use and ACS development.

The ACS incidence was higher in the bronchiectasis cohort than in the comparison cohort in all sex-, age- and comorbidity-specific subgroups. Men exhibited a higher incidence of ACS with a 1.31-fold increased risk of ACS compared with women after adjustment for covariates. The risk of ACS was significantly higher in patients aged 50 years and above than in those aged 34 years and below, suggesting the need for proactive multidisciplinary management of ACS for patients aged 50 years and above.

Compared with non-bronchiectasis patients without comorbidity, the bronchiectasis patients without comorbidity exhibited a higher risk of subsequent ACS but did not reach statistical significance because limited number of bronchiectasis patients did not have any comorbidity. Most of the patients with bronchiectasis (87.6%) had medical comorbid disorders. The patients with bronchiectasis and comorbidity showed a 2.82-fold increased risk of ACS development.

The strength of this study is its longitudinal design and the large population-based sample size; it is the first study evaluating the subsequent risk of ACS in patients with bronchiectasis in an Asian population. The NHI programme is universal and mandatory in Taiwan, and all NHI beneficiaries are assigned personal identification numbers that facilitate tracking patients throughout the follow-up period.

Several limitations should be considered while interpreting these findings. First, the detailed personal lifestyle demographics, for example, smoking and body mass index (BMI), is not available in the LHID2000, both of which are potential confounding factors in this study. However, COPD is a well-established comorbidity associated with cigarette smoking,36 and hence, we adjusted for COPD to serve as a surrogate of smoking.37 A significant association exists between BMI and risks of hypertension, CHD and stroke.38-40 We controlled for hypertension, CHD and stroke to mediate the influence of BMI. Second, bacterial colonization and lung function values are not available in the LHID2000, which may have influenced the outcomes of interest of this study. Third, the lack of drug-treatment data, namely, the use of hormone replacement therapy, anticoagulants and antiplatelet medicine, might have the impact of the outcomes.

In this cohort study of 3521 patients (17 340 person-years) with bronchiectasis, those with bronchiectasis exhibited a 40% higher risk of ACS than those without bronchiectasis. Patients with bronchiectasis experiencing frequent respiratory infections are at a high risk of ACS. Thus, clinicians should be aware of the phenomenon and carefully evaluate and holistically treat patients with bronchiectasis.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge administrative support from the Taichung Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare and Central Taiwan University of Science and Technology. No additional external funding received for this study.