Learning to live with reintroduced species: beaver management groups are an adaptive process

Author contributions: RA designed the research, collected data, undertook analysis, and drafted the initial text; all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript; SB, RB provided further supervisory advice throughout the project.

Abstract

In anthropogenic landscapes, wildlife reintroductions are likely to result in interactions between people and reintroduced species. People living in the vicinity may have little familiarity with the reintroduced species or associated management, so will need to learn to live with the species in a new state of “Renewed Coexistence.” In England, Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber) are being reintroduced and U.K. Government agencies are currently considering their national approach to reintroduction and management. Early indications are this will include requirement for “Beaver Management Groups” (BMGs) to engage with local stakeholders. This policy paper reports on qualitative research that captured lessons from the governance of two existing BMGs in Devon (south-west England), drawing on both a prior study and new interview data. Through the analysis, we identified that BMGs are not a fixed structure, but an adaptive process. This consists of three stages (Formation, Functioning, and Future?), influenced by resource availability and national policy direction. We argue that, where they are used, Species-specific Management Groups could provide a “front line” for the integration of reintroduced species into modern landscapes, but their role or remit could be scaled back over time and integrated into existing structures or partnerships to reduce pressure on limited resources, as knowledge of reintroduced species (such as beaver) grows and its presence becomes “normalized.” There must be sufficient flexibility in forthcoming policy to minimize constraint on the adaptive nature of BMGs and similar groups for other reintroduced species, if they are to facilitate a sustainable coexistence.

Implications for Practice

- Species-specific Management Groups for reintroduced species such as beaver are one possible approach to renewing coexistence, but they are not static; they must be an adaptive process.

- Species-specific Management Groups could be a “front line” to the integration of missing species in modern landscapes, helping local people to coexist alongside as populations establish.

- Populations will grow and, in the case of beaver, disperse into new river catchments. If Species-specific Management Groups are expected in every catchment, pressure on resources will increase.

- Reintroduced species will become more familiar over time. Accordingly, there may be less need for Species-specific Management Groups so their activities could be integrated into day-to-day actions of existing structures/bodies, reducing resource pressure.

Introduction

Wildlife reintroductions are often undertaken to contribute toward ecological restoration (Seddon et al. 2014; Corlett 2016). Reintroductions involve returning a species to a locality in which it previously existed but is now locally extinct (Seddon et al. 2014). Where this occurs in anthropogenic landscapes, interactions between people and reintroduced species are likely to manifest (O'Rourke 2014; Coz & Young 2020; Brazier et al. 2020a). In many instances, people living in the area will be familiar with a landscape in which that species has been absent, and so be unfamiliar with how to coexist, perhaps leading to human-wildlife conflict (Auster et al. 2020a). Consequently, reintroductions will be a learning process as people and reintroduced species learn to live alongside (Auster et al. 2020a, 2022c).

Renewed Coexistence refers to the process of fostering coexistence between people and reintroduced species (Auster et al. 2022c). There can be resulting benefits for the environment (e.g., restoration of trophic cascades; Ripple & Beschta 2012) and for people in ecosystem service provision (e.g., wildlife tourism; Auster et al. 2020b; Morling 2022).

There can be challenges too as conflicts with reintroduced species can result (Coz & Young 2020; Auster et al. 2020a). In the absence of effective and socially acceptable management approaches, conflicts could escalate and lead to reintroduction failure, preventing coexistence and associated benefits (Sutton 2015; Lopes-Fernandes & Frazão-Moreira 2017; Auster et al. 2020c). Reintroduction projects will need to anticipate challenges and prepare approaches for successful integration of species into anthropogenic settings, if they are to foster coexistence in the long term (O'Rourke 2014; Auster et al. 2020c, 2022c). Such approaches will minimize conflicts, enable opportunities to accrue, and enable the reintroduced species to remain within the landscape (Frank 2016; Auster et al. 2022c).

There are multiple possible approaches to Renewing Coexistence, the most appropriate of which will be context-dependent upon both species and human factors at regional scales. In this policy paper, we draw on a social study to document and learn from one approach to renewing coexistence with a lost species: the use of Species-specific Management Groups for reintroduced Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) in England.

We first provide contextual understanding of beavers and their reintroduction in England, before describing the study background and social research method. We then demonstrate that Species-specific Management Groups are an adaptive process through discussion of how they change over time. Finally, we conclude with a call for flexibility in policy to provide the space for Species-specific Management Groups to adapt over time.

Eurasian Beaver

Eurasian beavers (hereon beavers) are semi-aquatic rodents that have been reintroduced to much of their previous European range (Gaywood 2018; Brazier et al. 2020b). They are currently being reintroduced to England following a circa 400-year absence (Brazier et al. 2020a). Beavers are ecosystem engineers with the ability to modify riverine landscapes via dam-building, canal building, foraging (including tree-felling) and burrowing behaviors (Brazier et al. 2020b). These activities lead to creation of complex, dynamic wetlands that support biodiversity (Stringer & Gaywood 2016; Law et al. 2019), and their dam-building can slow water flows through landscapes, reducing flooding downstream (Puttock et al. 2020; Auster et al. 2022b) and increasing drought and fire resilience (Fairfax & Whittle 2020). However, these same activities can conflict with different stakeholder interests. For example, water held behind dams may cause localized flooding of property, or beavers may fell socially significant trees (Campbell-Palmer et al. 2016; Rosell & Campbell-Palmer 2022). A range of management approaches exist where beavers are present elsewhere that utilize practical techniques to prevent or minimize negative impacts (Campbell-Palmer et al. 2016). In England, details on a national approach to management are only just emerging and, among the wider human population, there can be a lack of familiarity of living with beavers and management techniques.

Current Situation in England

Following a 5-year reintroduction trial (Brazier et al. 2020a), the U.K. Government legally protected beavers in October 2022. Over 25 beaver enclosures have been licensed, and small wild populations (of unknown source) have been identified in several river catchments (Heydon et al. 2021).

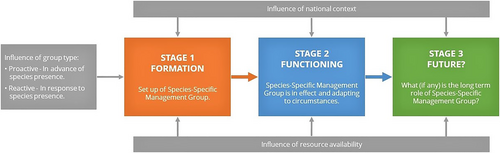

DEFRA (UK Government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) and Natural England are deliberating the national approach to beaver reintroduction and management. In Autumn 2021, DEFRA ran a public consultation on their proposed approach and, within consultation documents, references were made toward a potential role for “Beaver Management Groups” (BMGs). These Species-specific Management Groups are intended as fora to engage local stakeholders and discuss management solutions (DEFRA 2021; Pouget & Gill 2021). We draw on learning from two existing BMGs in South-West England to identify three stages in the process and inform potential development of BMGs nationwide and further afield: Formation, Functioning, and Future?

Research Background

In December 2021, Natural England contracted the authors to capture lessons from governance of the River Otter and River Tamar BMGs, providing evidence for decision-making. The final report (Auster et al. 2022a) is also intended as a learning resource for other BMGs. We drew on findings from a previous qualitative survey of River Otter Beaver Trial (ROBT) Steering Group stakeholder experiences (Auster et al. 2022c) and explored applicability to other contexts through deductive thematic analysis of new qualitative semi-structured interview data; themes identified in Auster et al. 2022c were applied as a coding framework to identify features in the data. In qualitative research, purposeful recruitment is often used to enroll participants with useful insights to enable a deep understanding of the contextual situation (Auster et al. 2020a). Here, interview participants (n = 10) were purposively selected individuals involved with the Tamar BMG, as members of lead organizations or as participating stakeholders. The project received ethical approval from University of Exeter's Geography Ethics Committee, interviews were conducted in person (or online) between January and March 2022, and the semi-structured interview questions are available in Auster et al. (2022a).

Through the analysis procedure, we observed that existing BMGs were evolving as circumstances changed and, although new in themselves, questions were already being raised about their long-term future. We draw on this analysis to describe the change over time, characterizing three stages we identified in this study (Fig. 1) and arguing this demonstrates that Species-specific Management Groups are not a fixed product, but are in themselves a dynamic governance process.

Formation

While there was an indication a small number of beavers may have been present in the 250 km2 catchment of the River Otter (Devon) as early as 2008, their presence was confirmed in 2013 when camera trap footage showed them to be breeding (kits were present). DEFRA originally intended for beavers to be removed from the river (Crowley et al. 2017) but, following a locally driven campaign and proposals from Devon Wildlife Trust (DWT), a license was granted to DWT to monitor beaver impacts over a 5-year period in the ROBT (Brazier et al. 2020a).

Now the Trial has concluded, ROBT governance is evolving into a BMG to engage more local stakeholders (e.g., local landowners and elected representatives) and provide localized management support.“We really thought [through] who was going to be likely to be affected by this, and who are people we need to take decisions” (participant 5).

On a parallel timeframe, a small population of beavers was identified in the nearby larger catchment of the River Tamar (approximately 1,820 km2). No organization was legally responsible for Tamar beaver management and no management fora existed until 2021, when DWT received funding to establish a BMG with support from Cornwall Wildlife Trust and Beaver Trust. Drawing on learning from the ROBT, a governance structure was established, including a Forum that meets annually and invites representation from a range of interests in the catchment. It aims to disseminate information and give opportunity for direct discussions with and between local stakeholders.

Furthermore, in the Formation stage there was significant investment in building relationships with individuals:“because of the way beavers use the landscape […] it should be a catchment scale […] It should be based on geographical boundaries, rather than political boundaries” (participant 4)

Relationship-building in wildlife management facilitates trust; where there is greater trust there is a higher likelihood of successful shared decision-making and conflict resolution (Decker et al. 2016; Auster et al. 2020a; Watkins et al. 2021).“we had lots of private meetings […] and then invited them to the forum. I would say that was probably quite a good approach because you're building relationships with people” (participant 4).

It is worth recognizing both BMGs were established reactively in response to beaver presence, rather than proactively in advance of their arrival. This was previously noted to have been a cause of tension for some in the ROBT (Crowley et al. 2017; Auster et al. 2020a, 2022c). Reactive BMGs may require higher investment in relationship-building to overcome pre-existing tensions and build trust, as opposed to proactive groups seeking to engage stakeholders prior to species arrival (Coz & Young 2020). Now beavers are a legally protected species, this will be important for people in neighboring catchments who will need to be prepared for the likely reality of beaver dispersal into their area, in the near future.

Functioning

Once relationships with initial group members have been established, BMGs can begin to function. As different people may experience benefits of beaver reintroduction to those who incur costs, a management approach that holistically considers the contrasting issues will be required (Brazier et al. 2020b). BMGs must be able to consider both potential benefits and negative impacts and involve both beneficiaries and cost-bearers within communities (Auster et al. 2022b) (see Brazier et al. 2020b for a review of beaver impacts and human–beaver interactions). Discussion must be respectful in tone to be inclusive of different viewpoints and enable stakeholders to feel their views are being considered, as reported among ROBT Steering Group stakeholders (Auster et al. 2022c). While individuals may hold different views or have different interests, constructive discussion will be key for maintaining trust and developing socially acceptable management solutions (Decker et al. 2016; Crowley et al. 2017).

In certain contexts, support for land-managers may continue to be needed if opportunities are to be maximized (Schwab & Schmidbauer 2003; Blewett et al. 2021). In future, it is possible there could be a role for financial incentives to support delivery of ecosystem services derived from beaver activity (Blewett et al. 2021). Meanwhile, DWT have recruited a Green Finance Officer who, as part of their remit, will identify green finance solutions to maximize beaver-related opportunities and minimize conflicts in Devon.“…it still is [resource heavy]. So in the long term [we] will have to encourage landowners to manage beavers more sustainably, as in, some of the beaver management will take place by landowners and farmers” (participant 3).

“membership […] needs to be dynamic, and reflect […] the constant changes of the population and where the focuses are in particular years and where the issues are arising that need to be discussed by that forum will change from year to year, depending upon what's happening on the ground […] it needs to be a movable feast. It needs to have new people coming onto it all the time, and some people will drop off it as well. People will lose interest, the beavers will have settled down in their area, and people will have less involvement in it” (participant 4).

Future?

Now we have demonstrated that BMGs change over time, this raises the question of “what next?.” This is already being considered by interviewees, who brought two elements to bear.

The second question is whether the need for BMGs will reduce over time as people learn to live with beavers? As membership changes in reflection of variation in beaver activities, and as people become used to their presence, there may be less requirement for as high a level of resource to be committed to such groups; it may become more efficient to integrate day-to-day management and conflict resolution into existing structures or organizations.“We then need to think about, do we need something to cover the whole of Devon? […] so if in five years' time we have beavers, let's say, not only on the Tamar and the Otter, but also on the Dart, the Exe, and the Taw/Torridge, […] we might need something that's rather bigger and looking strategically over a whole county, and then maybe some others which are perhaps more locally based” (participant 5).

While this can be further explored in time, we suggest the integration of remits could be an important factor in the normalization of a species as a “wild” animal rather than “reintroduced,” contributing toward a reduction in expectations for a management response and consequently reducing pressure on resources (Auster et al. 2020a):“I mentioned about catchment partnerships and there's obviously other things like Local Nature Partnerships, and the like. And I think obviously a proliferation of groups can cause difficulties for organisations to engage” (participant 2).

“what does the future of those look like as it becomes more normal? And maybe, after a while, you don't need [BMGs] anymore because people know how to beaver-proof areas. Maybe they've got a fixed lifespan, those groups” (participant 10).

External Influences: Resources and National Policy

The case study BMGs have been actively considering appropriate use of resources (e.g., the Tamar BMG Forum will take place on an annual basis so as not to become an onerous commitment for stakeholders, and it has a slimmed down governance structure compared to the ROBT, which was especially resource-intensive to address nationally significant research questions). However, as beavers become more widespread and colonize multiple catchments, the effectiveness of a group could be limited if the same resource is required in every catchment, by extension restricting potential to meet the aims of reintroduction. One of the ROBT/Tamar BMG leads highlighted this as a key point for national policy consideration:“It's quite a significant commitment. And we've been lucky that we've had some funding to do it this year. It takes quite a lot of time because its all of the actions that come from these groups as well” (participant 4).

This leads us to the second external influence: national policy. Beavers became a legally protected species in October 2022. There is likely a future role for BMGs (DEFRA 2021; Pouget & Gill 2021), but detail is only just emerging on the national approach to beaver management. Thus, there are questions and uncertainties about implications of national policy for beaver management within catchments, which may affect the scope of BMG activities. Participants raised several questions in this area, for example:“we're not going to be able to fund all of this externally forever. And funders […] aren't going to fund us in every county. […] at the beginning of this, going back six/seven years we were in a position to throw our core resources at [the ROBT] […] We wouldn't have been able to do that for 5 years non-stop, particularly as it grew. We would have had to pull out if we hadn't got external funds. And I think, when DEFRA considers what is required for new releases, it's going to have to be realistic about what funds people are going to be able to raise […] There was absolutely no point where we had guaranteed funding for 5 years, let alone ten” (participant 5).

- What management activities will be permitted (or require licensing) under new legal protective status for beavers?

- Will BMGs be required for every river catchment?

- What will U.K. Government expect BMG remits to include?

- What relationship might there be with statutory agencies?

Interview participants said indications beavers will be legally recognized had provided confidence to openly discuss beavers within the Tamar, but development of a management strategy had been paused until detail is released, to enable adaptation to changing circumstances.

Conclusion

BMGs may be one possible route toward renewing coexistence with beavers. At the time of writing, they appear to be part of the U.K. Government's favored approach for beavers in England. We argue they cannot be a fixed outcome; BMGs are a dynamic process that must have the capacity to adapt to changing circumstances. Species-specific Management Groups could be beneficial in reintroductions by providing a moving “front line” for involving local actors and familiarizing them with reintroduced species and management actions as the species reestablishes. For there to be a space in which groups can operate, there must be flex in forthcoming policy to ensure they are effective and able to adapt during the period of species integration.

Management Groups for reintroduced species are resource intensive. Resource limitations could reduce effectiveness, particularly as populations of reintroduced species grow. In this case, BMGs in England may become unsustainable to maintain long term as beavers colonize multiple catchments. This said, as people learn to live with reintroduced species, the need for Species-specific Management Groups may reduce and their role could be scaled back over time. As beavers or other species become ever more familiar, day-to-day management—to maximize benefits and minimize conflicts—could be integrated into existing bodies, organizations, groups, or structures. We suggest this is an important consideration if the species is to be as one which is “wild” rather than “reintroduced,” resulting in less resource-intensive governance for coexistence in future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all research participants from both the River Otter and River Tamar contexts. They would also like to thank D. Pouget, J. Hoggett, and J. Eaton for their support of the project. The research was funded by Natural England.