Malignant Seminoma in Two Unilaterally Cryptorchid Stallions

Contents

Two unilateral cryptorchid stallions were referred to the clinic because of chronic debilitating condition with emaciation. Rectal examination, and ultrasound and gross examination revealed in both animals an abdominal mass, caudally of the kidney, and multiple nodules spread over the abdomen. Histologic analysis revealed an intra-abdominal malignant seminoma with intraperitoneal and renal metastasis. Interestingly, a seminoma was also present in the descended testis of the draught horse.

Introduction

As many stallions, especially when cryptorchid, are castrated, the incidence of testicular neoplasia is unknown and presumed to be low (Schumacher 1999). Nevertheless, several testicular tumours are reported in horses and classified based on cell origin: germ cell-, sex cord stromal cell tumours and tumours with other cell origin. Seminoma and teratoma are the most common testicular neoplasia (Valentine 2009). Age predilection or influences of cryptorchidism in the development of testicular neoplasia in horses are not clearly established (Schumacher 1999; Valentine 2009). Seminomas are often reported as single cases (Vaillancourt et al. 1979; Gibson 1984; Trigo et al. 1984; Smith et al. 1989; Hunt et al. 1990; Sherman et al. 1990; Veeramachaneni and Sawyer 1998; Beck et al. 2001; Christensen et al. 2007; Govaere et al. 2010). Although both the cryptorchid and the descended testes can be affected, simultaneous neoplastic transformation has not been reported (Schumacher 1999). This study describes the clinical and pathological features of intra-abdominal malignant seminoma in detail and the simultaneous occurrence of a seminoma in the descended and undescended testis.

Case

Clinical findings

A 16-year-old Shetland pony stallion was presented in lateral decubitus after considerable weight loss over a 2-week time period. Elevated heart rate (52 beats/min) and bilateral absence of bowl sounds on abdominal auscultation were noted. A 12-year-old draught horse was presented with similar symptoms, that is weight loss, tachycardia (120 beats/min), fever (39.8°C) and heavy breathing.

External examination of the genital tract revealed that in both patients, the right testis was absent from the scrotum. The contralateral descended testis of the Shetland pony was removed earlier by castration.

The left descended testis of the draught horse had multiple hard nodules on its surface. Rectal palpation of the draught horse stallion revealed an enlarged, hard, abdominal right testis and multiple nodules diffusely distributed in the mesentery. Abdominal ultrasound showed free abdominal fluid, a big abdominal mass with different echo densities at both abdominal sides and multiple nodules in the liver and spleen. Abdominal ultrasound was not performed in the Shetland stallion, and the size of the Shetland precluded a rectal examination.

Blood examination revealed in both stallions a mild increase in polymorphonuclear cells, a severe lymphocytopenia and increased levels of urea, AST, CK, LDH and GGT. The Shetland stallion had a leucocytosis (24.4 × 109/l; normal value 3.5–9.0 × 109/l) and an elevated sero-creatinine level (980 μmol/l; normal value 88–172 μmol/l). The draught horse on the other hand had a neutrophilia (89%; normal value 45–70%), decreased albumin level (2.2 g/dl; normal value 2.5–4.5 g/dl) and an increased level of total protein (7.7 g/dl; normal value 5.5–7.5 g/dl), and α- (1.0 g/dl; normal value 0.2–0.5 g/dl) and β-globulins (2.0 g/dl; normal value 0.6–0.9 g/dl) (Table 1).

| Shetland pony stallion | Draught horse stallion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Normal value Laboratory reference | Result | Normal value Laboratory reference | |

| Polymorphonuclear cells, % | 85 | 55–70 | 89 | 45–70 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 15 | 30–45 | 7 | 20–45 |

| Leucocytes | 24.4 × 10 9 /l | 3.5–9 × 109/l | 10.9 × 1000/μl | 5.5–12 1000/μl |

| Neutrophils, % | 85 | 55–70 | 89 | 45–70 |

| Total protein | 8 g/dl | 6–8 g/dl | 7.7 g/dl | 5.5–7.5 g/dl |

| Urea | 76 mmol/l | 4–8 mmol/l | 72 mg/dl | 20–40 mg/dl |

| AST | 1650 U/l | 127–427 U/l | 1850 U/l | <540 U/l |

| CK | 3490 U/l | 10–146 U/l | 808 U/l | <275 U/l |

| LDH | 4060 U/l | 246–658 U/l | 1850 U/l | <350 U/l |

| γ-GT | 51 U/l | 1–18 U/l | 89 U/l | <45 U/l |

| Creatinine | 980 μmol/l | 88–172 μmol/l | 1.1 mg/dl | 0.8–1.8 mg/dl |

| Albumin | – | – | 2.2 g/dl | 2.5–4.5 g/dl |

| α-globulins | – | – | 1.0 g/dl | 0.2–0.5 g/dl |

| β-globulins | – | – | 2.0 g/dl | 0.6–0.9 g/dl |

- In bold all abnormal values compared to the normal reference values.

The poor prognosis resulted in the decision to euthanize both horses.

Gross examination

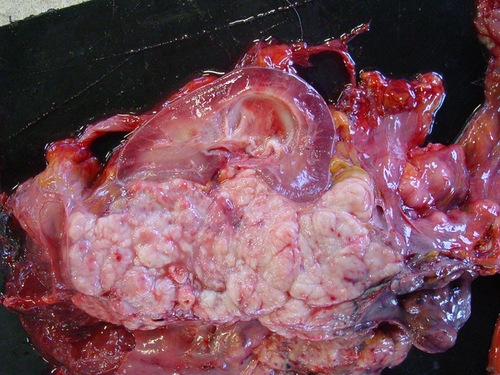

In the Shetland pony, the intra-abdominal right testis of was pathologically enlarged (10 × 7 × 10 cm) containing multiple exophytic nodules. On the cut surface, the mass was white spongy with central necrosis. Furthermore, on macroscopic inspection, the left kidney was enlarged by a spongy mass (10 × 20 × 15 cm) at the level of the renal pelvis and pelvic dilatation of the kidney (hydronefros) was present (Fig. 1). Lymph nodes of the rectum, colon, caecum and mesentery were enlarged (Fig. 2). Multiple masses covered the peritoneal surface.

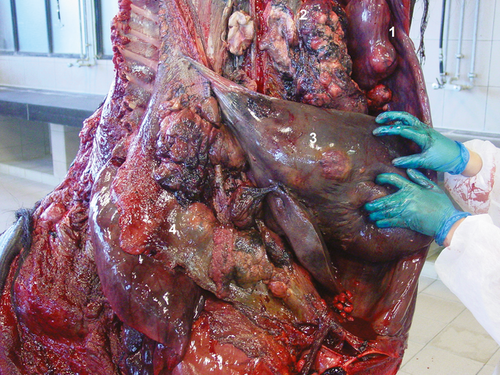

In the draught horse, both testes were neoplastic. The right intra-abdominal testis measured more than 20 cm in length (30 × 20 × 15 cm), containing multiple spongy masses (Fig. 3). The left descended testis was atrophic (5 × 7 × 5 cm) with multiple nodules in the parenchym, which were visible on the surface. Both seminal ducts were enlarged. Multiple metastasis at the level of the peritoneum, at the visceral side of the diaphragm and in the liver, spleen, ligamentum gastrolienale and omentum were found. The right kidney was neoplastic, measuring 60 × 25 × 30 cm with necrotic and haemorrhagic zones (Fig. 4).

Histological and immunohistochemical examination

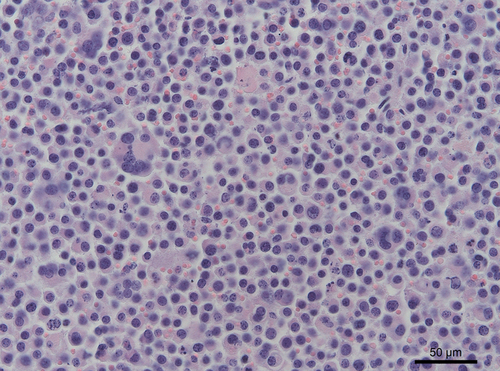

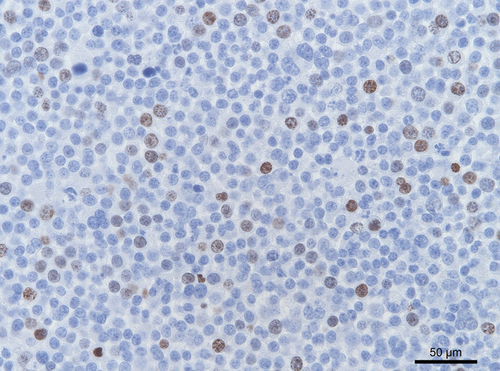

All samples of the Shetland had a similar appearance on haematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining: round cells with a large nucleus and prominent nucleolus. In the draught horse, the tumour revealed a tubular growth pattern with round to polyhedral cells. All the metastases had the same morphology. In both horses, anisokaryosis and multinucleate giant cells were present. Mitotic figures were common (0–1 per hpf) (Fig. 5). The right testicle of the draught horse showed a homogeneous mass of loosely arranged tumour cells with atypical cells. In both animals, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining demonstrated the presence of glycogen in the cytoplasm of neoplastic cells.

Immunohistochemical analysis for CD3 (T-cell lymphocytes), CD79a (B-cell lymphocytes) and MHCII (antigen presenting cells and lymphocytes) was negative, excluding lymphoma. Immunolabelling for smooth muscle actin excluded the masses as being leiomyoma/leiomyosarcoma. Neurone-specific enolase (NSE) and c-kit markers were, respectively, negative and variable positive. Ki67 immunolabelling confirmed the high proliferation rate in both animals (Fig. 6).

Both testicular neoplasia were diagnosed as seminoma.

Discussion

In horses, seminomas occur more frequently than other testicular neoplasias (Edwards 2008). The cause is yet unknown, but hormonal imbalances seem to be involved (Bahrami et al. 2007). In humans, cryptorchidism appeared to cause a distinct increase in testosterone to oestrogen metabolism due to aromatase overexpression (Hejmej et al. 2005; Bilinska et al. 2006). The excess oestrogens may lead to a suppression of insulin-like 3, responsible for testicular descent and is associated with a series of male reproductive disturbances, including testicular neoplasia (O'Donnell et al. 2001; Hejmej et al. 2005). In animals, inadvertent exposure of a pregnant dam to oestrogenic or anti-androgenic agents could result in testicular dysgenesis (Amann and Veeramachaneni 2006). Ganjam and Kenney (1975) showed higher oestrogen- and lower androgen levels in bilateral cryptorchid stallions in comparison with normal stallions or geldings. So, cryptorchidism may be a predisposition for or a consequence of the development of testicular neoplasia in the horse.

Seminomas in horses have a greater potential to metastasize than in other animals, and several, although limited, observations have been published (Valentine 2009). Yet, as far as we know, the presence of a large metastatic renal mass associated with cryptorchid seminomas has not yet been described in horses nor in other species. In humans, rare cases of seminomas with metastases to kidney or ureter have been described. It is proposed that this occurs through spread of the tumour to the primary drainage area near the hilum of the kidney, followed by retrograde involvement of the ureter, via the network of lymphatics, coursing along the spermatic vein and ureter (Johnson et al. 1981). As a very large metastatic mass in the ipsilateral kidney of the draught horse was observed, this phenomenon could have occurred. Yet, in the Shetland pony, involvement of the contralateral kidney most probably occurred through widespread metastasis.

In the present case, immunohistochemistry identified the masses as seminoma. Although markers for equine seminomas are not available, smooth muscle cell- or lymphocyte origin was ruled out by use of cell-specific markers. As in human seminoma, neurone-specific enolase (NSE) and c-kit are valuable markers (Kang et al. 1996; Chieffi and Chieffi 2013), they have been used in these equine tumours. In dog, c-kit has also been demonstrated to be a marker for seminoma (Yu et al. 2009). In contrast to these findings, the equine seminoma samples did not show a convincing positive labelling. Therefore, the diagnosis of seminoma was based on the morphologic features as well as the positive PAS staining.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Author contributions

V. De Lange was involved in collecting all information and writing the article; V. De Lange and C. Ververs in research; L. Lef__e in clinical diagnosis and therapy; M. Cools and K. Chiers in the pathological examination; K. Chiers and J. Govaere in the revision of the manuscript.