Evolving Motivation in Public Service: A Three-Phase Longitudinal Examination of Public Service Motivation, Work Values, and Academic Studies Among Israeli Students

Abstract

What are the impact of work values and academic training on public service motivation (PSM) over time? We present findings from a three-phase longitudinal study on the evolvement of PSM of Israeli students who gradually enter the job market. A cohort of 2,799 students were surveyed in late 2012 and a surviving final cohort of 558 respondents took part in the third stage of data collection during early 2015. We analyzed this group's postgraduate career development when they joined various public and nonpublic organizations and professions. We tested several hypotheses about possible relationships between and effects of work values (intrinsic–extrinsic; individualistic–collectivistic), academic studies, and person-organization fit and PSM over time. In general, individuals with higher levels of intrinsic and collectivistic values, and an academic background in core public service studies demonstrated stronger PSM over time. Implications and suggestions for future studies are discussed.

Evidence for Practice

- Human resource departments in the public sector should be aware of changes in employees’ public service motivation (PSM) over time.

- People's field of study is relevant for their PSM, beyond its relevance for a specific job.

- Intrinsic–extrinsic values as well as individualism–collectivism values may be used as criteria in selecting new public servants.

- Tracking transformations in work values may help improve PSM over time.

- Public sector organizations should improve the person-organization fit as it has special meaning for encouraging PSM over time.

Introduction

Public service motivation (PSM) has emerged as an important concept in the public administration literature, theoretically, empirically, and practically. The concept builds on the rationale that the success of the public sector relies on the motivation and resources of its workers (Baroukh and Kleiner 2002). The better we understand PSM and the willingness to serve the public, the closer we are to providing better public goods and meeting citizens’ expectations (Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi 2014). Consequently, the recruitment of highly motivated individuals for the public sector is a major challenge for governments and for public administration. Scholars have tried to respond to this challenge by creating new models to understand the drivers and impacts of PSM in various settings and population groups such as high school graduates, newcomers to public service, and private and public sector employees.

The importance of PSM is rooted in a variety of studies that have utilized different research foci. For example, some studies have focused on the meaning of PSM and the theory behind it (e.g., Perry 1996, 2000). Others demonstrated the significant relationship between PSM, moral behavior, and desirable organizational behavior (e.g., Bangcheng and Perry 2016; Kjeldsen 2012; Perry et al. 2008). Additional studies explored the relationship between PSM and employees’ job satisfaction (e.g., Taylor and Westover 2011; Wrighe, Cristensen, and Pandey 2013), organizational commitment (e.g., Bakker 2015; De Simone et al. 2016; Ugaddan and Park 2017), formal and informal job performance (e.g., Andersen, Heinesen, and Pedersen 2014; Kroll and Vogel 2014; Wright and Grant 2010), the attractiveness of the sector (Asseburg and Homberg 2020), intentions to leave the job (e.g., Caillier 2016; Campbell and Im 2016), and abnormal and nonconformist behaviors (Koumenta 2015). Most of these studies have been conducted among already functioning public servants (e.g., Houston 2000; Kim 2009; Ritz 2009) or a specific group of professionals (e.g., Kjeldsen and Jacobsen 2013).

Our study builds upon another wave of research that focused on PSM at the pre-entry–pre-employment stage (e.g., Carpenter, Doverspike, and Miguel 2012; Clerkin and Coggburn 2012, Kjeldsen 2012; Korac, Saliterer, and Weigand 2019; Pedersen 2013; Piatak 2016). We try to add to the knowledge about PSM by looking at its evolvement among students over time (e.g., Kim 2021) and track their PSM from the beginning of their academic studies to the beginning of their new careers. Our major question focuses on the impact of work values and prior academic background of these students on their PSM during the time of academic training and the early career stages. To do so, we propose a theoretical model that associates PSM with several work values both directly and indirectly and test it using a longitudinal design. This approach may also have the advantage of establishing causality arguments and findings. More specifically, we investigate the role of personal values (intrinsic–extrinsic and individualistic–collectivistic) and higher education (core–noncore public service studies) in the development of PSM over almost 30 months. By doing so, we also try to extend the knowledge on the dynamics of PSM over time (e.g., Vogel and Kroll 2016), and research about the tendencies of students to choose public sector oriented jobs (e.g., Tschirhart et al. 2008; Van der Wal and Oosterbaan 2013). We theorize that according to the public service ethos of working for citizens, serving the public interest, and contributing to the public good (e.g., Bright 2005), students with stronger intrinsic values, more collectivistic values, an education in core public service studies, and those for whom the public sector fits well with their values will demonstrate greater PSM over time. To test our model and hypotheses, we use a panel study and focus on three major points in time (the pregraduation stage, the beginning of one's career, and a year after entering a new job). In the next sections, we present our rationale, model and hypotheses, describe the field study, and explain the findings and their implications.

Theoretical Background

PSM: Essence and Construct

Over the years, PSM has been defined in various ways (e.g., Brewer and Selden 1998; Perry and Wise 1990). The most prevalent definition is by Vandenabeele (2007) who argued that PSM stands for “belief, values and attitudes that go beyond self-interest and organizational interest, that concern the interest of a larger political entity” (547). This definition, as well as others, indicates that people with high levels of PSM want to help others and are more concerned about the collective, communal, and social challenges set by governments, the public, and society as a whole. A series of studies such as Perry and Wise (1990) and Perry, Hondeghem, and Wise (2010) characterized PSM as having three components: (1) motives and actions in the public sphere designed to benefit others and contribute to the welfare of society; (2) altruistic goals and intentions that involve self-sacrifice and motivate the individual to serve the public interest, state, nation, or humanity as a whole; and (3) faith and an ethos that go beyond the personal and organizational good. Individuals with a strong PSM are those who are committed to the public interest and want to serve others and have a positive effect on society (Vandenabeele 2008).

Three major explanations have been offered for the rise and fall in PSM among individuals (Bright 2009; Perry and Wise 1990). First, people may be drawn to public service by rational motives arising from personal interests (i.e., rational motivation). Second, people may be attracted to public work for normative reasons such as social decency and an altruistic desire to serve the public interest (i.e., normative motivation). And finally, people may recognize the effectiveness of public work and its social contribution (i.e., affective motivation). These three categories (rational, normative, and affective) include the various incentives for working in the public service, and therefore, have been identified as the basis for the factors behind the decision to work in this sector (Clerkinet et al. 2009; Perry 2000). Hence, Perry (1996) presented four theoretical dimensions of PSM: (1) Attraction to policy making—a rational motivator for public service work; (2) Commitment to the public interest—a normative element identified with public service and the source of civil duty; (3) Compassion—an emotional motivator of an overwhelming sense of love for all people within the public system and a sense of duty to protect their rights; and (4) Self-sacrifice—another emotional motivator that represents the desire to provide service to others while giving up tangible rewards in favor of emotional rewards. These four dimensions represent individual needs that public service fulfills. The fourth dimension, self-sacrifice, differs from the other three and represents the unique conception of motivational theories in public administration (Camilleri 2007).

Perry (1996) used all of these theoretical dimensions to create a 24-item PSM scale. Since that time, our knowledge in this field has developed further (Kim 2009; Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann 2016; to name only a few) to include other drivers of investment in PSM. These drivers include personal identification with the values of public service (i.e., equity and the fair distribution of national resources), emotional identification with social goals, a desire to serve, patriotism, and generosity (Bright 2009). These findings imply that PSM may include other values, facets, and dimensions that reflect solidarity with others and the willingness to make an extra effort to serve the public.

In line with these studies, personal and organizational values seem essential for a better understanding of PSM across populations, professions, and over time. The relationship between PSM and values may be a promising path for a better understanding of what makes public service a desirable goal for potential employees. Recently, Asseburg and Homberg (2020) found a relationship between German students’ PSM and the attractiveness of the sector based on common values. They cited Wright and Pandey (2008b) who argued that PSM has much in common with work-related values and suggested that it might even overlap with the concept of public values (Andersen et al., 2013). Thus, one explanation for PSM may lie in the fit between people's values and those of the potential sector, workplace, or organization. Indeed, the congruence between an individual's values and the organization's values, frequently represented by the concept of person-organization fit (POF; Kristof 1996; Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson 2005), merits further examination in connection with PSM. Asseburg and Homberg (2020) maintained that people are attracted to organizations promoting values they share. This contention also accords with Schneider's (1987) Attraction–Selection–Attrition model (ASA) regarding the stages of the recruitment process and the reasons for choosing one employer over another, and staying with that employer for an extended period of time. Hence, POF may play a major role in the first stage of attraction when potential employees consider the match between the job and/or organization and their own values.

Several studies have mentioned values in general, particularly work values and POF, as important for explaining PSM and the decision to join the public service (e.g., Christensen and Wright 2011; Vandenabeele 2008). We, therefore, follow Asseburg and Homberg (2020) and Christensen and Wright (2011) who argued that “PSM's effects may be a function of the degree to which an organization shares the individual's public service values or provides opportunities for the employee to operationalize/satisfy these values” (724). To extend these views and in line with other studies (e.g., Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann 2016; Vandenabeele, Ritz, and Neumann 2017), we maintain that other work values such as individualism–collectivism, intrinsic–extrinsic values, and POF deserve further examination in their relationship with PSM, especially over time.

How Does PSM Evolve Over Time?

How does PSM evolve over time in light of potential changes in one's values and one's fit with potential employers? This evolvement results from dynamics within the workplace as well as from shifts in people's values and preferences. The increasing importance of PSM to the development of public administration both as a discipline and as a profession requires a better understanding of its evolvement over time, especially among newcomers to public service, and with regard to changes in their values during their training and careers.

Past studies provide some clues in this direction. Crewson (1997) and Houston (2000), supported by more recent studies (e.g., Kim 2021; Quratulain and Khan 2015; Wright and Grant 2010), suggested that over time, organizational factors affect PSM. The most prominent organizational factors are role hierarchy, employee-supervisor relations, leadership, occupational characteristics, attitudes toward and perceptions about the organization, the nature of organizational changes, the clarity of the employee's role and the importance of the task, seniority, and bureaucracy (Camilleri 2007). Studies indicate differences in PSM levels according to the employee's hierarchical ranking (Desmarais and Gamassou 2014). As employees are promoted, their need to serve the public increases. Therefore, they exhibit higher levels of PSM (Bright 2005; Camilleri 2007). Employee-supervisor relationships may also affect PSM: the better the employee's relationship with the manager, the higher the PSM level. In addition, Moynihan and Pandey (2007) reported that “employee-friendly” organizational changes also increase the level of PSM. Similarly, Carpenter, Doverspike, and Miguel (2012) pointed to POF as another important predictor of PSM. Other studies found that the clarity of the employee's role and the importance of the task increase the level of PSM (Camilleri 2007; Jacobson 2011). However, organizational characteristics may also negatively affect PSM (Giauque 2012; Perry et al. 2008; Scott and Pandey 2005).

Although these studies and more recent ones (e.g., Ingrams 2020; Ki 2020) have contributed significantly to our understanding of the evolvement of PSM, especially with regard to work values and the fit between these values and those of public service employees, some pieces of the puzzle remain missing. For example, what happens to PSM over time, especially with regard to work values, and particularly among newcomers to public service with different educational backgrounds and training? Can people's predispositions and values predict their PSM? More specifically, what is the impact of intrinsic–extrinsic values, individualistic–collectivistic values, POF, and type of education or academic studies on PSM over time? Our model and hypotheses address these questions.

Model and Hypotheses

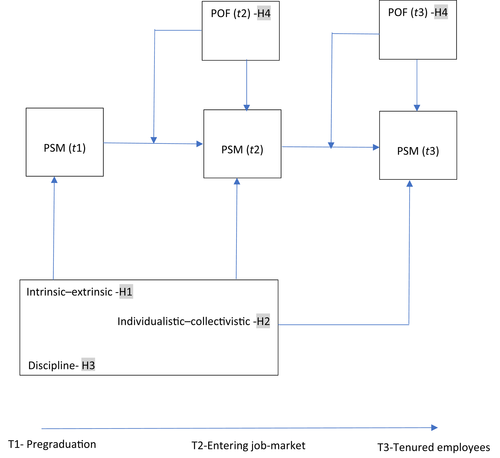

To explore these questions, we propose a model in which various work values of the individual, especially those values evident prior to holding a specific job or joining a specific organization, affect PSM. We focus on individualistic–collectivistic values, on intrinsic–extrinsic values, and on people's professional training and academic studies. We also try to explore the moderating role of POF after joining a specific organization in explaining the relationship between work values and PSM over time (figure 1).

Intrinsic–Extrinsic Work Values and PSM

According to Schwartz (1992, 1994), work values are important for employees and for the entire organization due to their relationship with work performance. Schneider's (1987) ASA suggests that work values play a major role in the job selection process. When there is a good match between people's values and those of the organization, the former is more likely to be hired by the latter and remain with the organization longer. There are different types of work values involved in this match. One of the most common is the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic values (Gesthuizen and Verbakel 2011; Kaasa 2011; Ros, Schwartz, and Surkiss 1999). Extrinsic work values involve economic benefits such as income, security in the job, flexible working hours, pension schemes, or insurance. These values are external to the individual, not to the way one works or to the content of one's work (Kaasa 2011). Thus, even if someone does not like the content of the work, he/she may still find it worthwhile and desirable for providing a good salary or other benefits. In contrast, intrinsic work values refer to the desired content of one's work, not the general circumstances of it. According to Arendt (2013, 140), intrinsic work values revolve around personal development and self-fulfillment in work. These values refer to the importance that an individual places on the “opportunities for further development of personal skills and an interest in the work promoted by the activity” (Tarnai et al. 1995, 140). Those who stress intrinsic values may prefer a job offering more autonomous decision-making, richer opportunities for exploring new horizons, learning, and developing a variety of skills. Thus, the focus is more on personally defined goals of work, instead of individual capital, wealth, or security (Bright 2009).

Gesthuizen, Kvarek, and Rapp (2019, 62–63) argued that people vary with regard to their intrinsic–extrinsic values and preferences for work. These intrinsic–extrinsic values and preferences depend on personality, on the impact of the social environment and socialization, and on maturity and life changes over time. Whereas in the early stages of people's careers, some may favor extrinsic values such as a job that offers economic benefits or flexible working hours, in later stages they may look for jobs that accord with intrinsic values such as self-fulfillment and a sense of duty.

Similarly, the emphasis on intrinsic or extrinsic work values and preferences may change as people's careers advance and they receive promotions and tenure in the organization. These changes may affect their PSM differently at different points in time. Some studies have argued that for public sector employees, intrinsic values come first, whereas for private sector employees the extrinsic ones are more important (e.g., Kalleberg et al. 2006; Lyons, Duxbury, and Higgins 2006). Thus, the favoring of intrinsic work values over extrinsic ones might predict PSM. Georgellis, Iossa, and Tabvuma (2011) found that intrinsic values trump extrinsic values when it comes to choosing a public employer. They thus suggested that intrinsic rewards increase the likelihood of choosing the public sector as a preferred employer, while extrinsic rewards do not affect this decision. Other studies investigated the impact of a pay-for-performance rewards system in public organizations and found that it may actually have a negative effect on intrinsic work values and motivation (e.g., Moynihan 2010; Perry et al. 2009). These authors suggested that such a system contradicts the core elements of the intrinsic values rooted in the raison d'etre of public organizations.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between intrinsic values and PSM (e.g., Georgellis and Tabvuma 2010; Houston 2000; Park and Word 2012). Two major findings of these studies and others were that (1) there is a clear theoretical and empirical distinction between PSM and intrinsic values (Belle 2013, 2014; Grant & Berry 2011), and (2) intrinsic values are positively related to PSM for employees working in the public sector (Brewer, Selden, and Facer 2000; Crewson, 1997; Perry & Wise, 1990). However, as far as we could find, no one has suggested or examined the relationship between PSM and intrinsic–extrinsic values among students and new job entrants or tracked it over time.

Based on the studies above and on Schneider's (1987) ASA model, we theoretically suggest a positive relationship between intrinsic values and PSM. We maintain that those individuals holding intrinsic values prior to entering the job market, will demonstrate higher levels of PSM over time. In contrast, we expect that extrinsic values will have no effect on PSM over time. Those who favor intrinsic values early in their careers will be more attracted to public service jobs that provide a better fit with these values. In contrast, those who favor extrinsic values will be more attracted to nonpublic jobs. Moreover, this idea is also in line with the expectancy theory (Vroom 1964). Assuming that students and new job entrants seek jobs that better match their expectations, views, aspirations, and values, those who favor intrinsic values will see the public sector as a more attractive employment venue and will express a greater level of motivation to work for the public. Over time, if these intrinsic work values accord with the values of the public organization in which they work, we expect the PSM of these individuals to remain strong. Alternatively, for those with more extrinsic work values, staying with the organization will not increase their PSM. Therefore, we posited that:

Hypothesis 1.Intrinsic and extrinsic values will be related to the PSM of students and newcomers to public service organizations over time. Higher levels of intrinsic values at t1 will have a positive effect on PSM over time (t2 and t3), whereas extrinsic values will have no effect on PSM over time (t2 and t3).

Individualism–Collectivism and PSM

The favoring of individualistic values as opposed to collectivistic values is one of the leading areas in which cultures differ from one another (e.g., Ghorbani et al. 2003). However, beyond this general context, individualism and collectivism have major implications for organizations and the public sector. The contrast between these values is widely discussed in the literature on organizational culture (e.g., Hui and Triandis 1986; Triandis 1995), and has received attention in public administration studies as well (e.g., Kim 2017; Mastracci and Adams 2019). Most of the studies on individualism and collectivism in the workplace build on the seminal works of Hofstede (1980, 1981, 1998) who suggested individualism and collectivism as one of his five core dimensions of culture. Thus, employees with higher levels of individualistic values will tend to be more autonomous, undervalue teamwork, and be more focused on personal needs, rather than on group level performance and interests. On the other hand, employees with more collectivistic values will tend to be team players, to place the common interest ahead of their own aspirations, and be willing to invest more resources in the collective good rather than personal gain (e.g., Ramamoorthy and Carroll 1998; Street 2009).

Accordingly, the impact of individualism–collectivism values on PSM seems plausible. We would expect people who favor collectivistic values to score high on the values associated with PSM over time because they are quite similar. Collectivistic values give priority to the needs of others, and prize sensitivity to team members and the collective good. These attitudes are much in line with the public ethos of serving citizens. The theoretical foundations and rationale for these arguments come from several directions. First, the use of organizational theories such as social construction and personality traits ideas in public administration strongly support this rationale (Christensen 2019). According to this approach, social construction within the public sphere builds over time from the stage of job selection to job socialization. Moreover, this idea is also clearly in line with Schneider's (1987) ASA theory and Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory. According to these ideas, new employees who favor collectivistic values will be more attracted to public service that highlights the mission of serving citizens and strengthening the collective goals of society, rather than just the private interests of only a few. These individuals are more likely to be selected to work in the public sector. Then, after entering the new job, they will be more likely to share information with others, will be more engaged in teamworking wherever possible, and will both contribute to and enjoy the mutual spirit of public service. As their careers develop, their expectations of the job or organization are more likely to be fulfilled, strengthening their PSM over time. Hence, those who see beyond their own self-interests are also those expected to be better motivated to work hard to achieve public goals.

In line with this rationale, we also expect that those who favor collectivism over individualism will also experience stronger PSM over time. Alternatively, new employees with more individualistic values are less attracted to public jobs, less likely to be chosen for them, and less likely to remain in them even if they are chosen. Therefore, we do not expect them to demonstrate greater PSM levels over time simply because they are less focused on the collective good. Moreover, as we will discuss in detail in the next sections, the POF theory supports this rationale quite strongly. It suggests that those who favor collectivism over individualism will find public service a better fit with their values than those with more individualistic values. Hence, we expect that people who favor individualistic values will pursue careers that provide them with personal gains and benefits, sometimes at the expense of other colleagues, clients, or citizens. Quite recently, and much in line with our theoretical arguments, Kim (2017) documented that people with collectivist values had higher levels of PSM than those who favored individualistic values. Therefore, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 2.Collectivistic and individualistic values will be related to PSM over time. Higher levels of collectivistic values at t1 will have a positive effect on PSM over time (t2 and t3), whereas individualistic values will have no effect on PSM over time (t2 and t3).

Discipline, Education, and PSM

Perry and Wise (1990) suggested that “the greater an individual's public service motivation, the more likely the individual will seek membership in a public organization” (370). Thus, we argue that the choice of an organization that is appropriate for the individual begins as early as choosing one's academic studies. Choosing a field of study is indicative of one's personal preferences, orientation, predisposition, intentions, and aspirations. Naturally, one's field of study has a major impact on choosing a profession or a future job (Taylor 2005; Vandenabeele 2008). The ASA theory is relevant here as well, as individuals may be more prone to study fields that match at least some of their work values. As a result, their later selection of a specific job will be based on these disciplines and education background. When there is a good match between people's values, their background education, and the values of the organization, they will be more likely to be hired by the organization and remain in the job longer. Lewis and Frank (2002) found that recruiting qualified employees and those with a stronger PSM increases the chances for success in public duty. Qualified employees are obviously those who have adequate academic training and knowledge in the relevant disciplines that contribute to public service. Thus, identifying individuals who have such skills and knowledge, and exhibit a stronger PSM in the early stages of their academic and professional training may help predict future public service performance and outcomes. Taylor (2005) investigated students’ work orientations and compared them with their educational background and experience in the job. He found significant differences among students from different disciplines in terms of their views on work values and compensation. For example, business administration students and law students ranked extrinsic values such as income, reputation of the job, and prestige much higher than students of political science, public policy, and education. The latter ranked intrinsic work values much higher and emphasized the importance of public ethics in the job. This study, as well as a previous work by Edwards, Nalbandian, and Wedel (1981), supports the argument that one's academic field of study may be related to work values such as intrinsic–extrinsic and individualism–collectivism.

Moreover, students of political science, public policy, and education expressed more intentions of joining governmental organizations and public administration and much less willingness to work in private sector organizations. A later study by Vandenabeele (2008) supported these findings and reported that one's academic discipline affected the attractiveness of potential future employers. Students who earned degrees in areas such as political science and social welfare were more attracted to government jobs than those who studied fields such as economics, business administration, and law. More recently, Huang (2021) found that although students’ PSM tends to change during the college years, their public administration education may not significantly contribute to its development. Hence, it was suggested that in-service training aiming to foster employee PSM should focus on the establishment and practice of service values.

Furthermore, a study by Kjeldsen (2012) was one of the few to use a longitudinal design in the context of academic discipline and PSM. Its findings largely supported previous findings on the stronger tendency for a PSM among students from core public service studies. Kjeldsen reported that the PSM level of these students remained stable throughout their years of study, but there was an increase in the PSM of other students who came from noncore public service disciplines. This quite surprising finding suggests that education level, in general, contributes to the development of PSM over time. It also accords with most other studies (e.g., Camilleri 2007; Pandey and Stazyk 2008) documenting that among public employees their PSM was positively related to their overall levels of education. Thus, we proposed a third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.PSM across academic disciplines will differ. Over time, students from core public service studies will demonstrate more PSM than students from noncore public service studies.

POF and PSM

In the previous hypotheses, we suggested relationships between various work values and PSM over time. We theorized about the centrality of the fit between people's values and public service with regard to intrinsic–extrinsic and individualistic–collectivistic values and about students’ academic background and employment in public service. Nevertheless, beyond these specific work values and academic background, our model also suggests that a general POF may have a direct and moderating effect on PSM over time.

What is the rationale for this relationship? The congruence between individuals and their workplace is embedded in the concept of POF, which represents the degree to which people's skills, needs, values, and personalities match the organization's requirements (Bretz and Judge 1994). Research has accumulated about the relationship between POF and PSM (e.g., Christensen and Wright 2011; Kim and Torneo 2021; Steijn 2008; Wright and Pandey 2008b), while some studies also focused on its meaning in higher education (e.g., Jin, McDonald, and Park 2018). Other studies also focused on the mediating role of POF in the relationship between PSM and work attitudes and job performance (e.g., Bright 2007; Kim 2012; Hue, Thai, and Tran 2021). Moreover, it has also been suggested that a better fit between the values of public servants and their organizations contributes to their performance and motivation to invest effort in public duty (Vigoda-Gadot and Meiri 2008). Likewise, Carpenter, Doverspike, and Miguel (2012) established a relationship between POF and PSM across sectors.

To advance these studies even further, we argue for both a direct and moderating role of POF in shaping levels of PSM over time. We suggest that POF may play a role in people's choice about where to work, as well as in their socialization when adjusting to their new role and duties (Bright 2016). When the POF is poor in one or more of the stages of a person's career (e.g., Schneider 1987), it is more likely that she/he will feel disappointed and frustrated, and gradually become alienated from the organization and his/her surroundings. Such feelings may broaden the emotional, psychological, and functional gap between a person and his/her workplace and may also result in a drop in PSM.

Numerous studies that confirmed a positive relationship between POF and PSM have suggested this rationale (e.g., Bradley and Pandey 2008a; Wright, Christensen, and Pandey 2013). We maintain that the theoretical rationale for the direct and indirect moderating relationships between POF and PSM is rooted in both Schneider's (1987) ASA theory and Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory, as well as in studies that highlight variables such as advancement opportunities, fairness, teamwork, and interactions with others as indicative of one's level of fit and compatibility with the workplace (e.g., Gould-Williams, Mostafa, and Bottomley 2013; Williamson, Burnett, and Bartol 2009). As explained earlier, the ASA theory of the attraction to and selection for a specific job or organization and staying with it in the long run largely depend on the congruence between individuals and the employer. If there is a good POF between people and the public service, we would expect their PSM to remain high or even increase over time. However, when the fit between the person and the organization is poor, we expect their PSM to decline over time. Similarly, with time, expectations of and experiences with issues such as promotion, fairness, and teamwork may improve or degrade the POF. Consequently, changes in the POF may increase or reduce people's willingness to invest effort in public service and public duties based on their fulfilled or unfulfilled expectations and aspirations. Thus, to maintain employees’ PSM, the structural, normative, and cultural aspects of the organizations in which they work must be in line with their expectations, and vice versa. Otherwise, we expect that their PSM will decline over time.

In fact, Blau's (1964) idea of social exchange provides another theoretical justification for the moderating effect of POF on PSM over time. Blau maintained that social exchange is an important mechanism that balances the employees’ needs and aspirations, and the goals and expectations of higher-ranking managers. Balanced social exchange mechanisms may imply a better fit between individuals, managers, and their work environment, which in turn may enhance PSM over time. When people's personal characteristics and attitudes are close to those of the organizations in which they work, we can expect a better fit between them and their environment due to a more balanced exchange mechanism. Hence, organizations that employ individuals who are a better fit with them maintain a healthy exchange system and are likely to benefit from their continued PSM. These employees will be more productive, provide better service, and perform better, with minimal absenteeism and turnover.

Therefore, beyond its direct relationship with PSM, POF may moderate changes in PSM over time as employees enter the organization, gradually digest their exact role in the workplace, and become more aware of their duties and mission (the selection and socialization stages). Initially, some may be very idealistic and thus strongly motivated to work for the public. With time, their expectations and exchange relations may vary, leading them to feel that the reality is more disappointing than initially expected. This disappointment is eventually reflected in a reduction in their sense of fit with the organization. Consequently, adjustments in their POF may also have an impact on changes in their PSM. A strengthening in their POF may increase the effect of their previous PSM on their current PSM, whereas a drop in their POF may work in the opposite way. This theoretical rationale also accords with other studies that suggested POF as a moderator in the relationship between PSM and other outcome variables such as exit intentions, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction (Gould-Williams, Mostafa, and Bottomley 2013). Thus, our final hypothesis posited:

Hypothesis 4a.Person-organization fit will have direct and indirect relationships with PSM over time.

Hypothesis 4b.Person-organization fit will moderate the relationship between PSM over time (t1–t2 and t2–t3). The PSM of students with a poor POF will decrease over time, whereas the PSM of students with a strong POF will remain stable and strong over time.

Method

Sample and Design

We developed a longitudinal study based on a panel sample with three repeated measures (t1, t2, t3) and intervals of around 15 months between t1 and t2 and similar intervals between t2 and t3. The first survey was distributed and collected in mid-2012 among students from a variety of disciplines (political science, education, welfare and health, social work, law, sociology, psychology, management, biology and natural sciences, computer science, economics, and humanities) in several Israeli universities and colleges. These students were in their final year before graduation and were about to earn a degree and enter the job market. The survey was distributed using an online platform and 3,411 students responded to our initial call to fill out the survey. A final number of 2,799 usable questionnaires were received at t1. The second wave of questionnaires was distributed in late 2013 to these respondents. By that time, these students had begun their careers and joined a variety of organizations and jobs in the market. In this wave, 992 usable questionnaires were returned at t2 (a response rate of 35.4 percent). The third wave of questionnaires was distributed to these respondents in mid-2015. During the time between t2 and t3, the students were more established in their workplaces, had earned tenure, and gained experience. In this wave, 558 usable questionnaires were returned at t3 (a response rate of 56.3 percent) and used in our final analysis. Of the final 558 respondents, 58 percent were women; average age was 30.9 years; 60 percent were unmarried; 88.8 percent were Jews; 31.7 percent had a core public service academic background; and 50.4 percent were employees in public organizations or professions. 1

Measures

PSM.

We followed the definition of Perry and Wise (1990) that PSM represents “an individual's predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions and organizations” (368). We used a 12-item scale based on Kim's (2009) shorter version of the original Perry (1996) scale that embodies the four internal dimensions of PSM: attraction to policy making, commitment to the public interest, compassion, and self-sacrifice. However, based on Organ's (1988) idea of Organizational Citizenship Behavior and the good soldier syndrome, at t2 and t3 we added three items representing a fifth dimension of going above and beyond one's job definition for the public. 2 Thus, we assessed PSM at t2 and t3 using 15 items. Sample items are: (1) Sharing my views on public policies with others is attractive to me, and (2) I consider public service as my civic duty. Responses ranged from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Reliability was 0.86, 0.87, and 0.84 (t1, t2, t3, respectively).

Intrinsic–Extrinsic Values.

Based on Crewson (1997) we used an eight-item scale with two sets of four items each for intrinsic and extrinsic values, respectively. Respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which each value was important for them on a scale ranging from one (not important for me) to five (highly important for me). Intrinsic values included a feeling of accomplishment, worthwhile accomplishment, useful to society, and help others. Extrinsic values included job security, high pay, promotion, and performance awards. This variable was measured at t1, and its reliability ranged between 0.72 (for intrinsic values) and 0.76 (for extrinsic values).

Individualistic–Collectivist Values.

A two-item scale was used reflecting dispositions toward other group members. It was based on a longer scale suggested by Wagner (1995) to reflect people's involvement in group dynamics and its importance for them. We used two items reflecting the supremacy of group goals: (1) A group is more productive when its members follow their own interests and concerns, and (2) a group is most efficient when members do what they think is best rather than what the group wants them to do. The scale for this measure ranged from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Reliability was 0.77 (t2).

Academic Training.

Based on the studies of Vandenabeele (2011) and Kjeldsen (2012) we measured this variable by dividing academic studies into two groups: (1) core public service studies and (2) noncore public service studies. In the first group, we included disciplines such as political science, education, social work, welfare, and health. In the second group, we included disciplines such as biology and natural science, economics, computer and exact sciences, humanities, law, business administration–management, sociology, and psychology.

Person-Organization Fit.

We followed Bright (2007) who suggested a four-item scale based on O'Reilly and Chatman (1986). The scale was used at t2 and t3. Sample items are: (1) my values and goals are similar to the values and goals of my organization and (2) I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization. Respondents were asked to report their answers on a scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Reliability was 0.87 and 0.84 (t2, t3, respectively).

Organization Type.

Students were asked to report where they work at t2 and t3. We classified the answers into two categories: (1) public and nonprofit sector–professions, and (2) private sector organizations–professions.

Analysis

We examined each wave of data separately for zero-order statistics to ensure the reliability, validity, and overall quality of the scales, lack of multicollinearity, and elementary relationships in accordance with the hypotheses. Once we had all of the data, we conducted an integrative analysis based on the final sample of 558 respondents who survived all three stages of the study. We used variance analysis to assess PSM across the independent variables using F-tests and t-tests for independent samples. For the longitudinal analysis, we used multiple regression analysis and repeated measures analysis with interactions to examine the moderation effects. These analyses testified to the power of the model and to some extent also the causal relationships among its constructs.

Findings

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics and intercorrelation matrix of all of the scales over time. According to this table, most of the zero-order correlations work in the expected directions. We established a positive relationship between intrinsic work values at t1 and PSM at t1, t2, and t3 (r = .29, p < .001; r = .45, p < .001; r = .36, p < .001, respectively). In addition, the higher the level of intrinsic values, the higher the level of PSM in the repeated measures. No relationship was found between extrinsic values and PSM at times t2, t3, and a weak positive relationship was evident between extrinsic values and PSM at t1. These findings are in line with 1. In addition, no relationship was found between the collectivist value of group work preferences at t1 and PSM over time (t1, t2, t3). This finding contradicts 2. We did document a positive relationship between POF at t2 and PSM over time (r = .27, p < .001; r = .41, p < .001, respectively for t2 and t3). The better the POF at t2, the higher the level of PSM at t2 and t3. Similarly, POF at t3 and PSM at t3 were strongly related (r = .69, p < .001). These findings accord with 4a and 4b. Finally, PSM at t1 and at t2 and t3 were strongly related (r = .60, p < .001; r = .51, p < .001 respectively). Thus, PSM at t1 is a solid predictor of PSM at later stages (t2 and t3).

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Public service motivation (PSM) t1 | 3.58 | 0.58 | (.86) | |||||||||

| 2. PSM t2 | 3.59 | 0.60 | .60*** | (.87) | ||||||||

| 3. PSM t3 | 3.50 | 0.56 | .51*** | .70*** | (.84) | |||||||

| 4. Person-organization fit (POF) t2 | 3.60 | 0.85 | .17*** | .34*** | .41*** | (.87) | ||||||

| 5. POF t3 | 3.79 | 0.73 | .45*** | .58*** | .69*** | .31*** | (.84) | |||||

| 6. Intrinsic t1 | 4.49 | 0.52 | .45*** | .36*** | .29*** | .21*** | .29*** | (.76) | ||||

| 7. Extrinsic t1 | 4.36 | 0.56 | .09* | .08 | .09 | .09* | .08 | .31*** | (.72) | |||

| 8. Individualism–collectivism t2 | 4.03 | 0.80 | .07 | .05 | .03 | −.03 | .08 | .16*** | −.01 | (.77) | ||

| 9. Educational field a | — | — | .09 | .07 | .11* | .08 | .07 | .06 | .05 | .02 | — | |

| 10. Age | 27.8 | 6.95 | .08 | .12** | .16** | .18*** | .10* | .14** | −.03 | .01 | .09** | — |

| 11. Gender b | — | — | .11* | .08 | .04 | −.04 | .03 | .20*** | .09* | .05 | .05 | −.03 |

- Note: N = 395–558 due to deletion of missing pairwise values.

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

- a Core public service fields of education = 1.

- b Woman = 1.

According to table 2, there was a significant difference in the level of the PSM of students from various fields of study during t1 (F = 14.05, p < .01). As 3 expected, students from fields of core public service exhibited higher levels of PSM than those from noncore public service disciplines. For example, the PSM scores for students in social work (M = 3.80, SD = .53), political science (M = 3.78, SD = .54), and education (M = 3.73, SD = .50) were significantly higher than those in computer science (M = 3.25, SD = .62), business administration–management (M = 3.40, SD = .57), psychology (M = 3.42, SD = .57), sociology (M = 3.48, SD = .60), biology (M = 3.52, SD = .51), and economics (M = 3.55, SD = .62). Similarly, these differences were quite stable during t2 (F = 6.40, p < .001). Students in social work (M = 3.74, SD = .51), political science (M = 3.79, SD = .59), and education (M = 3.83, SD = .48) exhibited higher PSM levels than those in computer science (M = 3.29, SD = .64), biology (M = 3.35, SD = .47), psychology (M = 3.42, SD = .45), business administration–management (M = 3.30, SD = .57), sociology (M = 3.50, SD = .57), and economics (M = 3.54, SD = .71). Similar findings were also found at t3 (F = 6.40, p < .001). Again, and in accordance with 3, students in social work (M = 3.74, SD = .51), political science (M = 3.79, SD = .59), and education (M = 3.83, SD = .48) reported higher PSM levels than those in computer science (M = 3.29, SD = .64), psychology (M = 3.36, SD = .48), economics (M = 3.38, SD = .76), biology (M = 3.44, SD = .49), sociology (M = 3.50 SD = .52), and business administration–management (M = 3.50, SD = .57).

| Variables | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Time | 2.26 (2, 385) | .11 |

| Gender | 0.92 (1, 386) | .34 |

| Age | 0.00 (1, 386) | .97 |

| Educational field | 18 (1, 386) | .001 *** |

| Extrinsic t1 | 1.38 (1, 386) | .24 |

| Intrinsic t1 | 58.65 (1, 386) | .001 *** |

| Individualism-collectivism | 16.87 (1, 386) | .001 *** |

| Person-organization fit (POF) | 10.93 (1, 386) | .001 *** |

| Organization type | 8.53 (1, 386) | .01 ** |

| Gender × time | 0.51 (2, 386) | .60 |

| Age × time | 0.54 (2, 386) | .58 |

| Educational field × time | 3.05 (2, 386) | .05 * |

| Extrinsic × time | 0.63 (2, 386) | .53 |

| Intrinsic × time | 16.66 (2, 386) | .001 *** |

| Individualism-collectivism × time | 0.29 (2, 386) | .75 |

| POF × time | 11.77 (2, 386) | .001 *** |

| Organization type × time | 0.12 (2, 386) | .88 |

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

- a N = 395–528 due to deletion of missing pairwise values.

To further establish the expected differences between students in core and noncore public service disciplines, we performed a t-test (for independent samples). Table 3 reports the findings of this analysis, which further supports 3 and establishes a significant difference between the PSM of these two groups. These differences hold over time for t1, t2, and t3 (t = −11.48, p < .001; t = −7.30, p < .001; t = −3.06, p < .01, respectively). The level of PSM of students with a background in core public service studies (M = 3.77, 3.76, 3.60; SD = .53, .54, .57) was significantly higher than that of students of noncore public service studies (M = 3.48, 3.46, 3.44; SD = .59, .58, .55, respectively).

| Variables | Core Public Service Fields of Education Mean (SD) | Other Fields of Education Mean (SD) | df | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public service motivation (PSM) t1 | 3.77 (.53) | 3.48 (.59) | 1,582 | −11.48*** |

| N = 718 | N = 1454 | |||

| PSM t2 | 3.76 (.54) | 3.46 (.58) | 831 | −7.30*** |

| N = 320 | N = 513 | |||

| PSM t3 | 3.60 (.57) | 3.44 (.55) | 335.30 | −3.06** |

| N = 173 | N = 350 |

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

To further examine the multivariate relationships between the independent variables and PSM at various points in time, we conducted a multiple regression analysis whose results appear in table 4. According to these findings, PSM at t1 was strongly related with intrinsic values (β = .52, p < .001), collectivist values (β = .11, p < .001), and a background in core public service studies (β = .22, p < .001). Similarly, PSM at t2 was also strongly related with intrinsic values (β = .32, p < .001), collectivist values (β = .07, p < .05), a background in core public service studies (β = .23, p < .001), and POF (β = .12, p < .001). Finally, PSM at t3 had no direct relationship with intrinsic values but was positively related to collectivistic values (β = .05, p < .05) and POF at t2 and t3 (β = .12, p < .001; β = .46, p < .001, respectively). The explained variance was 26, 19, and 51 percent for t1, t2, and t3, respectively. In other words, the power of the model at t3 was quite strong, especially due to the impact of POF (t2, t3), which emerged as a much stronger predictor among all of the exogenous variables. Overall, these findings support 1, 2, 3, 4a, and 4b. For these hypotheses, we may also infer some causality, especially for the variables measured over time.

| Variables | PSM t1 (N = 516 d) | PSM t2 (N = 501 d) | PSM t3 (N = 395 d) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SD | β | B | SD | B | B | SD | β | |

| Gender a | .02 | .05 | .02 | .06 | .05 | .05 | .06 | .04 | .05 |

| Age | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .00 | .00 | .02 |

| Educational field b | .22*** | .05 | .16 | .23*** | .05 | .17 | .05 | .04 | .04 |

| Extrinsic t1 | −.05 | .04 | .05- | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | −.00 | .04 | −.01 |

| Intrinsic t1 | .52*** | .05 | .44 | .32*** | .05 | .27 | .05 | .05 | .05 |

| Individualism–collectivism t2 | .11*** | .03 | .17 | .07* | .02 | .10 | .05* | .02 | .08 |

| Organization c | — | — | — | .00 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .04 | .00 |

| POF t2 | — | — | — | .12*** | .03 | .02 | .12*** | .03 | .17 |

| POF t3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | .46*** | .03 | .60 |

|

F (6,509) = 31.30*** Adjusted R2 = .26 |

F (8,492) = 15.28*** Adjusted R2 = .19 |

F (9,385) = 45.82*** Adjusted R2 = .51 |

|||||||

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

- a Woman = 1.

- b Core public service fields of education = 1.

- c Public and nonprofit organizations = 1.

- d N = 395–558 due to deletion of missing pairwise values.

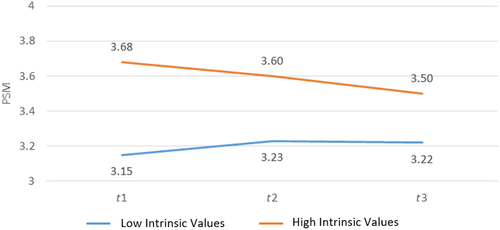

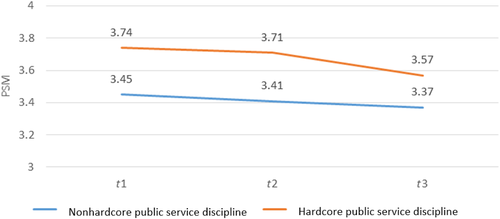

To test the change in PSM over time, we used a repeated measures variance analysis. This analysis is presented in table 5. It examined the change in PSM from t1 to t2 and to t3 by intrinsic–extrinsic values, individualism–collectivism values, POF, and academic studies, as well as gender and age. The Wilks’ Lambda test revealed that time by itself had no overall effect on PSM (F = 2.26, n.s.). However, over time people's academic studies (F = 18.00, p < .001), intrinsic values (F = 58.65, p < .001), collectivistic values (F = 16.87, p < .001), POF (F = 10.93, p <. 001), and the type of organization in which they worked (F = 8.53, p < .01) affected their PSM. The interactions of time and academic background, intrinsic values, and POF were also significant, suggesting that these factors play an important role in PSM. These interactions are detailed in figures 2-4.

| Variable | Core Public Service Disciplines | Other Disciplines | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | ED | WH | SW | SOC | PSY | MAN | LAW | HUM | CS | SS | Other | ECO | BIO | F Test | |

| PSM t1 | 3.78 | 3.73 | — | 3.80 | 3.48 | 3.42 | 3.41 | 3.57 | 3.56 | 3.25 | 3.53 | 3.78 | 3.55 | 3.52 | F = (13,2591) |

| SD | 0.540 | 0.50 | — | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 14.05 ** |

| N | 290 | 300 | — | 128 | 125 | 235 | 124 | 100 | 137 | 136 | 202 | 152 | 178 | 217 | |

| PSM t2 | 3.79 | 3.83 | 3.60 | 3.74 | 3.50 | 3.42 | 3.50 | 3.70 | 3.69 | 3.29 | 3.45 | 3.93 | 3.54 | 3.35 | F = (14, 958) |

| SD | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 6.40 *** |

| N | 109 | 99 | 65 | 47 | 51 | 91 | 35 | 38 | 60 | 65 | 48 | 37 | 48 | 74 | |

| PSM t3 | 3.50 | 3.75 | 3.53 | 3.62 | 3.50 | 3.36 | 3.43 | 3.70 | 3.69 | 3.34 | 3.41 | 3.80 | 3.38 | 3.44 | F = (14, 545) |

| SD | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.49 | 2.20 ** |

| N | 51 | 49 | 41 | 32 | 36 | 73 | 28 | 23 | 51 | 53 | 25 | 12 | 21 | 40 | |

- # Abbreviations: BIO, biology; CS, computer science; ECO, economics; ED, education; HUM, humanities; MAN, management; PS, political science; PSY, psychology; SOC, sociology; SS, other social sciences; SW, social work; WH, welfare and health.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

According to figure 2, the interactive effect of intrinsic values on the relationship between time and PSM was significant (F = 16.66, p < .001). Furthermore, differences between low and high levels of intrinsic values had varying effects on PSM between t1 and t2 (F = 16.13, p < .001). Overall, students with high levels of intrinsic values exhibited stronger PSM than students reporting low levels of intrinsic values (e.g., 3.68 vs. 3.15 at t1). However, over time, the level of PSM for students with high levels of intrinsic values decreased between t1 and t3 (from 3.68 to 3.50), whereas for students with low levels of intrinsic values, PSM rose slightly (from 3.15 to 3.22; F = 33.17, p < .001). This finding provides support for 1.

According to figure 3, the interactive effect of academic background on the relationship between time and PSM was significant (F = 3.05, p < .05). There was no clear difference in PSM between students with a background in core and noncore public service studies between t1 and t2. However, there were differences for the period between t2 and t3. During that time, PSM decreased among students with a background in core public service studies (from 3.71 to 3.57; F = 5.09, p < .05), whereas the change among noncore public service students was marginal (from 3.41 to 3.37). The decrease in PSM among students with a background in core public service studies between t1 and t3 was even greater (from 3.74 to 3.57; F = 3.79, p < .05), whereas for other students it remained quite stable. This finding supports 3.

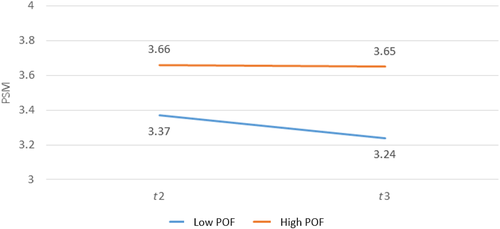

According to figure 4, the interactive effect of POF on the relationship between time and PSM was significant (F = 11.77, p < .001). We found a significant difference between students with a strong and weak POF over time. In other words, the PSM of students joining the job market at t2 who exhibited a strong POF was stable (3.66 vs. 3.65), whereas the PSM of students reporting a weak POF at t2 decreased (from 3.34 to 3.24) and these differences were significant (F = 9.96, p < .01). This finding accords with 4b positing a moderating effect of POF on PSM over time, especially for those with a weak POF.

Discussion and Summary

Recruitment of highly motivated public servants is an ongoing battle of governments worldwide to provide better services to citizens and maximize public goods for society. Therefore, scholars have paid increasing attention to the factors that result in the successful recruitment of public personnel (e.g., Bright 2009; Coyle-Shapiro and Kessler 2003; Kettlt 2005, to name only a few). One of the strongest indicators of the quality and potential of these public servants is their PSM. Those who have such a motivation to help public and nonprofit organizations perform better, create effective, efficient, moral, and quality governance, and develop social resilience (Andersen, Heinesen, and Pedersen 2014; Perry, Hondeghem, and Wise 2010; Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann, 2016).

This study tries to fill a gap in the literature that lacks sufficient knowledge about how PSM develops and evolves over time among individuals prior to joining the workforce (e.g., Houston 2010; Kjeldsen 2012; Vandenabeele 2008). Whereas theory suggests a variety of factors that play a role in the decision to go into public service (e.g., HighHouse, Lievens, and Sinar 2003), most of our knowledge about the development of PSM is cross-sectional. We argue that people's values and predispositions toward public service are important factors that might improve the explanatory power of PSM over time.

Thus, our paper confirms the relationship between PSM, intrinsic and collectivistic values, and academic background. It also points to the important direct and indirect role of POF as crucial to the understanding of PSM over time. One unique contribution is the support that our longitudinal study found for these relationships. Such support adds to the current knowledge from previous cross-sectional studies (e.g., Bright 2016, 2018). Moreover, based on our longitudinal design, we can also infer that these relationships are causal, at least to a certain extent.

The finding about the centrality of intrinsic and collectivistic values for the better engagement of employees in general (e.g., Street 2009) and especially for explaining PSM over time accords with the existing literature and with theories such as Schneider's (1987) ASA theory, Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory, and Blau's (1964) exchange theory. We support the findings by Houston (2010) and Georgellis, Iossa, and Tabvuma (2011). However, we also add to that knowledge by suggesting that people's intrinsic and collectivistic values that exist prior to joining the job market may also affect their PSM when they are attracted to and selected for public service jobs, and in later stages of their career development. In other words, such values, which are formed with no relation to a specific workplace (and may be subject to personality traits, socialization processes, or other environmental and cultural differences), may affect PSM in a specific workplace and over time. However, the impact of these values gradually diminishes. Over time, other organizational-related variables such as POF become more important and have implications for the expectancy and exchange types of relationships with the organization. As we explained earlier, a strong level of PSM is often evident among very idealistic individuals when first starting out in public organizations. However, the reality of work in such organizations might be disappointing. As a result, they may feel that they are not as good a fit with the organization, a feeling that reduces their PSM as well. Thus, a strong POF may increase the effect of their previous PSM on current PSM, while a weak POF will have the opposite effect. This finding extends previous studies such as Steijn (2008) by adding the longitudinal and causal dimensions and overcoming the limitations of one-time measurements.

Our findings also generally accord with those of Brewer et al. (2000) and Anderfuhren-Biget et al. (2010) who found that extrinsic values are not typical of employees with high levels of PSM. Indeed, the relationship is sometimes even negative. Validating Ward's (2014) study, we confirm that time is meaningful for the evolvement of PSM. Whereas the impact of early values and predispositions, such as intrinsic values and collectivistic values, on PSM is strong in the early stages of people's careers, it declines significantly in the presence of organization-related factors such as POF. These findings have theoretical as well as practical implications.

Theoretically, our findings extend our knowledge about the complex relationship between PSM and POF that scholars such as Jin, McDonald, and Park (2018) suggested. One major explanation for this process is Mortimer and Lorence's (1979) theory of organizational socialization. According to their model, tenure, and experience in the workplace shape motivation more strongly than other personal and personality factors. Our findings about (1) the decrease in PSM among individuals who reported high levels of intrinsic values in the early stages of their career and (2) the relatively consistent impact of extrinsic values and collectivistic values on PSM over time support this contention. Given that extrinsic conditions are quite fixed and are not subject to change over a short period (e.g., salary, benefits, flexible time, etc.), their impact on PSM is quite steady. Moreover, individualistic–collectivistic values may be largely shaped prior to entering the job market. While they may have a positive relationship with PSM at different stages, they do not explain changes in PSM over time. This latter finding is quite in line with Kim's (2017) study on the positive relationship between collectivism and PSM.

On the practical level, our findings underscore the centrality of organization-related factors in explaining PSM over time. The implications for the public sector and other service-oriented organizations cannot be underestimated. Skilled managers and leaders can promote their employees’ PSM by highlighting the quality of service they provide and emphasizing that they are making a difference and contributing to others through their work. Programs for developing managerial skills among public servants should devote time and other resources to encouraging the ability of public sector managers to promote PSMs among their subordinates.

Another major contribution is the extension of Kjeldsen's (2012) study on the relationship between people's academic field of study and their PSM. We reconfirmed this relationship quite strongly, suggesting that it holds not only at one point in time but also over time, although it decreases gradually. Our findings demonstrate a direct relationship between these variables. Thus, they are somewhat complementary to those of Pedersen (2013) who pointed to academic background as a moderator between PSM and attraction to public versus private sector employment. One implication of these findings may be that an academic background in core public service studies is positively related to or strongly influences people's PSM, especially at the beginning of their careers and in the early stages of working for a public organization (Schneider 1987). However, with time, the impact may diminish and other factors, probably organizational ones like POF, become stronger and more crucial. The centrality of POF that was evident in our study accords with other studies (e.g., Bradley and Pandey 2008a; Christensen and Wright 2011; Gould-Williams, Mostafa, and Bottomley 2013), and again highlights the growing impact of intra-organizational factors on PSM over time, over and above any other personality and personal factor. Finally, our findings also reveal differences in PSM across students from various disciplines, and also a relatively stable level of PSM within each group over time.

One theoretical explanation for these findings is the “reality shock” of understanding and digesting the actual meaning of working for public and governmental agencies with all its typical bureaucracy and formality (Kjeldsen and Jacobsen 2013). The theoretical implications of these findings are noteworthy. Future models of PSM should take into consideration people's academic background in core–noncore public service disciplines as another independent variable to explain PSM. Such studies should also examine both personal and personality variables, along with organizational variables at various levels (individual, team, and organization) in relation to PSM over time. In addition, public human resource managers searching for new, talented, qualified public servants should take these factors into consideration.

Beyond its potential contribution, the study presented here obviously has limitations. First, this study is based on self-reports of individuals and thus has the potential risk of common-method and common-source bias. Second, despite its longitudinal design, we suggest that inferences about causality be made with caution. Beyond the advantages of analyzing a panel data like ours, there are weaknesses rooted in within-group changes that may bias our results, especially when causality is considered. Third, due to reliability problems, our measure of collectivistic values used only two items, which is marginal in terms of scale validity. Therefore, we encourage future studies to use a richer measure with additional items referring not only to team level but also to other levels. In addition, we measured PSM at t2 and t3 in a slightly different form than the conventional approaches suggested by Kim (2009) and others. While those studies used a four-dimension scale, we added a fifth dimension based on the idea that highly motivated public sector employees should be willing to extend themselves for the public. This idea is rooted in Organ's (1988) concept of the “good soldier syndrome.” Although it worked well in our study, we recommend that future studies retest its validity and reliability. Doing so may enrich our understanding about the borders of PSM, clarifying its connection with extra-role behaviors for the public suggested in previous studies (e.g., Koumenta 2015). Finally, our reliance on an Israeli sample may be culturally biased. Thus, we encourage future studies to replicate our study in other countries.

Yet, all in all, we believe that the contribution of our study outweighs its limitations and that we added significant knowledge to the exploration and understanding of PSM over time and in a more causal context. We believe that such findings also have practical uses for human resource managers in the public sector, as well as for policy makers who rely on PSM in their daily work for the public.

Notes

Biographies

Rotem Miller-Mor-Attias is a faculty member at the Division of Public Administration and Policy, School of Political Science, University of Haifa. She is the head of the MPA program in Local Government Administration and specializes in public service motivation. The paper is based on her PhD Dissertation.

Email: [email protected]

Eran Vigoda-Gadot is a Professor of Public Administration and Management at the Division of Public Administration and Policy, School of Political Science, University of Haifa. He served as Head of the School and as Dean of the Paul and Herta Amir Faculty of Social Sciences. Founder of the Center for Public Management and Policy (CPMP) and an author and co-author of many articles, books, and other publications and working papers in the field of public management, organizational behavior, governance, and human resource management.

Email: [email protected]