Should children receive a kidney transplant before 2 years of age?

Abstract

Background

The optimal age of kidney transplantation for infants and toddlers with kidney failure is unclear. We aimed to evaluate the patient survival associated with kidney transplantation before 2 years of age versus remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years.

Method

We used the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to identify all children added to the deceased-donor waitlist before 2 years of age between 1/1/2000 and 4/30/2020. For each case aged <2 years at transplant, we created a control group comprising all candidates on the waitlist on the case's transplant date. Patient survival was evaluated using sequential Cox regression. Dialysis-free time was defined as graft survival time for cases and the sum of dialysis-free time on the waitlist and graft survival time for controls.

Results

We observed similar patient survival for posttransplant periods 0–3 and 4–12 months but higher survival for period >12 months for <2-year decreased-donor recipients (aHR: 0.32; 95% CI: 0.13–0.78; p = .01) compared with controls. Similarly, patient survival was higher for <2-year living-donor recipients for posttransplant period >12 months (aHR: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.06–0.73; p = .01). The 5-year dialysis-free survival was higher for <2-year deceased- (difference: 0.59 years; 95% CI: 0.23–0.93) and living-donor (difference: 1.84 years; 95% CI: 1.31–2.25) recipients.

Conclusion

Kidney transplantation in children <2 years of age is associated with improved patient survival and reduced dialysis exposure compared with remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years.

Abbreviations

-

- aHR

-

- adjusted hazard ratio

-

- aOR

-

- adjusted odds ratio

-

- HRSA

-

- Health Resources and Services Administration

-

- HHRI

-

- Healthcare Research Institute

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- IRB

-

- Institutional Review Board

-

- OPTN

-

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

-

- SRTR

-

- Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

-

- UNOS

-

- United Network for Organ Sharing

-

- USRDS

-

- United States Renal Data System

1 INTRODUCTION

According to the 2022 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) annual data report, the incidence of kidney failure is 27 cases per million for infants, 8 cases per million for children 1–12 years of age, and 16 cases per million people for those 13–17 years of age.1 In addition to having the highest incidence of kidney failure, infants have the highest adjusted mortality within 1 year of kidney failure onset and the highest waitlist mortality in the United States.2, 3 Hence, it is important to examine therapies and interventions that may improve survival among this patient population.

Kidney failure requires dialysis or a kidney transplant for survival. Compared with chronic dialysis, kidney transplantation is associated with a survival benefit, enhanced growth, superior neurocognitive outcomes, and improved quality of life.4 However, kidney transplantation is seldom offered to children less than 2 years of age. A recent registry data report from Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan showed that only 17% of children with kidney failure within the first month of life received a kidney transplant before 2 years of age.5 Existing studies evaluating the outcomes of kidney transplants performed in infants and toddlers are few and do not explicate the ideal age for transplant within this age group. A retrospective study of 51 pediatric patients weighing <15 kg at the time of transplant found 5-year graft survival of 100% with intraperitoneal kidney placement and 91.7% with extraperitoneal placement.6 Another study of 226 pediatric kidney recipients weighing <20 kg reported favorable outcomes with mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ranging between 90 and 104 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 5 years posttransplant.7 The optimal age for transplantation among children with infantile kidney failure remains uncertain. Whether the risks of surgical complications outweigh the benefits associated with early transplantation remains unknown.

The objective of this study was to compare the patient survival associated with a kidney transplant performed before 2 years of age (<2-year transplant) with that of remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years. To evaluate the risk of graft failure not resulting in death for recipients transplanted before age 2 years while maintaining the same follow-up start time for candidates remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years, we compared 5-year dialysis-free survival between the two groups. Extrapolating from the survival benefit of early transplantation in older children,8, 9 we hypothesized that transplants performed before 2 years of age are associated with a patient survival benefit compared with remaining on the waiting list until older. We also hypothesized a higher 5-year dialysis-free survival for <2-year transplant recipients compared with those remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the survival benefit of kidney transplantation before 2 years of age compared with delaying the transplant until ≥2 years.

2 METHOD

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Minnesota approved this study.

2.1 Data source

We utilized data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) for this study.10 The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.11 The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available in SRTR.

2.2 Study population

We identified all kidney transplant candidates in the United States who were listed on the deceased-donor waitlist before 2 years of age between 1/1/2000 and 4/30/2020. Of the waitlisted candidates, those who underwent a kidney transplant before age 2 years were identified as cases. For each case, we created a comparison/control group consisting of all waitlisted candidates listed before 2 years of age and who were on the waitlist on their respective case's transplant date.

2.3 Study variables

We examined the following characteristics of the study participants: age at kidney failure, age at listing, age at transplant, gender, race, pretransplant dialysis/preemptive transplant, cause of kidney failure, blood type, prior transplants, cause of graft loss, and cause of death.

2.4 Study outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was patient survival. We also compared 5-year- restricted dialysis-free survival between patients transplanted before age 2 years and those who remained on the waiting list until ≥2 years of age. Dialysis-free survival was defined as graft survival for <2-year transplant recipients and a sum of dialysis-free period, if any, on the waitlist and graft survival for recipients transplanted ≥2 years. We also evaluated eGFR for patients transplanted before and after 2 years of age. The eGFR was estimated using the modified Schwartz equation.12

2.5 Statistical analysis

We summarized categorical measures using counts and proportions and reported continuous measures using medians and interquartile ranges.

We used sequential stratification or sequential Cox approach to evaluate patient survival benefit, if any, associated with transplantation before 2 years of age versus remaining on the waiting list until older (≥2 years). We conducted separate analyses for deceased-donor and living-donor recipients. For the deceased-donor analysis, all deceased-donor transplants performed before age 2 years among waitlisted candidates were considered cases. For each decreased-donor transplant case, we created a control group consisting of all candidates waitlisted before 2 years of age and on the waitlist on their respective case's date of transplant. We followed each case and the corresponding control group from the case's transplant date to the earliest of the dates of death or the last follow-up. We censored the follow-up on waitlist control's date of transplant if the control subsequently received any transplant before age 2 years or a living-donor transplant after age 2 years. Similarly, the follow-up was censored if the waitlist control was removed from the waitlist without a transplant. Each case with the corresponding control group was a separate “experiment” (also known as “stratum” or “landmark”). Waitlist control patients could be part of multiple strata. Waitlist candidates could serve as both cases (in one stratum) and controls (in one or more other strata) if they received a deceased-donor kidney prior to age 2 years. We used a similar strategy to evaluate patient survival associated with <2-year living-donor transplants compared with remaining on the waiting list until older, censoring waitlist controls at the time of any kidney transplant prior to age 2 years, a deceased-donor transplant after age 2 years, or if removed from the waitlist without transplantation.

We compared patient survival between cases and control groups using stratified Cox models, with cluster-robust variance estimates to account for patients appearing in more than one stratum. Due to evidence of non-proportionality of hazards, we also stratified these models by posttransplant period (0–3, 3–12, and > 12 months) to obtain a separate hazard ratio for each period. Models were adjusted for age at the case's transplant date, gender, race, blood type, pretransplant dialysis, insurance type, and center size.

To compare graft survival time between the two treatment strategies while maintaining the same starting time for recipients and matched waitlist controls and allowing for controls who do not receive a transplant or receive a kidney from a different donor type, we chose an analogous measure, dialysis-free time, for comparison. The starting time for dialysis-free time computation was the transplant date for the stratum (case and corresponding control). For cases, dialysis-free time equaled graft survival time, whereas for waitlist controls, dialysis-free time was the sum of dialysis-free time on the waitlist, if any, beginning at the case's transplant date, and graft survival time, with censoring occurring as described above (transplant with different donor type than the case patient, transplant before age 2 years, end of follow-up, or removal from the waitlist). Five-year-restricted dialysis-free time was calculated in each stratum for up to 5 years of follow-up from the starting time. Five-year-restricted dialysis-free time was compared between groups using inverse probability of censoring weighting to account for patients who were censored prior to 5 years of follow-up. The probability of censoring was estimated using a Cox model adjusting for gender, race, age, blood type, pretransplant dialysis, insurance type, and center size. Confidence intervals for the weighted mean 5-year-restricted dialysis-free time in each group and for the difference between groups were estimated using a bootstrap procedure with 1000 replicates.

Analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2 including the survival version 3.4-0 package.

3 RESULTS

Between 1/1/2000 and 4/30/2020, 1217 children <2 years of age were added to the kidney transplant waitlist. Of these, 39% were transplanted before age 2 years, 40% were transplanted between ages 2 and 5, and 4% died while on the waiting list.

The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. Of the patients, 556 (46%) received a decreased-donor transplant, and 423 (35%) received a living-donor transplant. The remaining 238 (20%) patients were either still waiting at the time of the analysis, had died while on the waitlist, or had been removed from it without a transplant.

| Variables |

All N = 1217 |

Deceased-donor transplant recipients N = 556 |

Living-donor recipients N = 423 |

No transplant (still on the waiting list, died, or removed) N = 238 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at kidney failure in months Median [IQR] | 7 [1, 18] | 7 [1, 19] | 9 [2, 20] | 5 [1, 9] |

|

Age at listing in months Median [IQR] |

16 [12, 20] | 17 [13, 20] | 16 [12, 20] | 16 [12, 20] |

|

Age at transplant in months Median [IQR] |

24 [19, 30] | 25 [21, 34] | 22 [18, 27] | – |

|

Gender n (%) Male |

870 (71%) | 399 (72%) | 304 (72%) | 167 (70%) |

| Race n (%) | ||||

| White | 967 (79%) | 410 (74%) | 376 (89%) | 181 (76%) |

| Black | 157 (13%) | 95 (17%) | 27 (6%) | 35 (15%) |

| Asian | 53 (4%) | 27 (5%) | 13 (3%) | 13 (5%) |

| Multiple | 23 (2%) | 13 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 5 (2%) |

| Native American | 9 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

| Pacific | 8 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

| Pretransplant dialysis n (%) | 838 (69%) | 421 (76%) | 270 (64%) | 147 (62%) |

| Prior transplant n (%) | 21 (2%) | 8 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 7 (3%) |

| Cause of kidney failure n (%) | ||||

| Acquired obstructive uropathy | 10 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| CAKUT | 511 (42%) | 225 (41%) | 184 (43%) | 102 (44%) |

| Cystic kidney disease | 117 (10%) | 53 (10%) | 40 (9%) | 24 (10%) |

| FSGS | 6 (0%) | 5 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 9 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| HUS | 13 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Other | 546 (45%) | 258 (46%) | 186 (44%) | 102 (44%) |

|

HLA mismatch Median [IQR] |

4 [3, 5] | 5 [4, 5] | 3 [2, 3] | - |

3.1 Deceased-donor transplants

Table 2 compares the characteristics of <2-year deceased-donor transplants and their corresponding controls. Median age at kidney failure for <2-year deceased-donor recipients was 6 months (IQR: 1, 13), and the median age at transplant was 20 months (IQR: 17, 22). Seventy-two percent of <2-year transplant recipients were male, and 74% were white.

| Variables | Recipients transplanted before 2 years (n = 238) | Control/comparison group (n = 793) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age at kidney failure, months Median [IQR] |

6 [1, 13] | 8 [2, 21] |

|

Age at listing, months Median [IQR] |

15 [12, 18] | 17 [12, 20] |

|

Age at transplant, months Median [IQR] |

20 [17, 22] | 27 [23, 35] |

|

Gender n (%) Male |

172 (72%) | 240 F (30%), 553 M (70%) |

|

Weight at transplant, kg Median [IQR] |

10.8 [9.8, 11.9] | 12.5 [10.8, 14.6] |

| Race n (%) | ||

| Asian | 11 (5%) | 34 (4%) |

| Black | 43 (18%) | 91 (11%) |

| Multi-racial | 6 (3%) | 11 (1%) |

| Native | 2 (1%) | 7 (1%) |

| Pacific | 1 (0%) | 6 (1%) |

| White | 175 (74%) | 644 (81%) |

| Pretransplant dialysis n (%) | ||

| Yes | 199 (84%) | 504 (76%) |

| Donor source n (%) | ||

| Living | 0 (0%) | 351 (53%) |

| Deceased | 238 (100%) | 315 (47%) |

|

Warm ischemia time, min Median [IQR] |

37 [25, 45] | 34 [25, 45] |

| Delayed graft function n (%) | 30 (13%) | 36 (5%) |

| Cause of kidney failure n (%) | ||

| Acquired uropathy | 4 (1.7) | 3 (0.4) |

| ATN | 5 (2.1) | 10 (1.3) |

| CAKUT | 82 (34.6) | 344 (43.4) |

| Cortical necrosis | 9 (3.8) | 21 (2.6) |

| Cystic kidney | 28 (11.8) | 74 (9.3) |

| GN | 2 (0.8) | 3 (0.4) |

| HUS | 3 (1.3) | 12 (1.5) |

| Malignancy | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Nephrotic | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.9) |

| Oxalate | 9 (3.8) | 10 (1.3) |

| Other | 95 (40.1) | 305 (38.5) |

| Cause of death n (%) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 1 (5.0) | 7 (11.5) |

| Cerebrovascular | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) |

| Graft failure | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.9) |

| Infection | 4 (20.0) | 12 (19.7) |

| Malignancy | 1 (5.0) | 2 (3.3) |

| Organ failure | 6 (30.0) | 12 (19.7) |

| Other | 6 (30.0) | 11 (18.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (5.0) | 12 (19.7) |

| Cause of graft loss n (%) | ||

| Chronic infection | 14 (28.0) | 39 (50.6) |

| Infection | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.9) |

| Other | 11 (22.0) | 14 (18.2) |

| Primary non-function | 3 (6.0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Recurrent disease | 1 (2.0) | 5 (6.5) |

| Rejection/hyper-acute rejection | 11 (22.0) | 5 (6.5) |

| Surgical/urological complication | 2 (4.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Thrombosis | 8 (16.0) | 8 (10.4) |

3.2 Deceased-donor transplants before age 2 years versus remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years

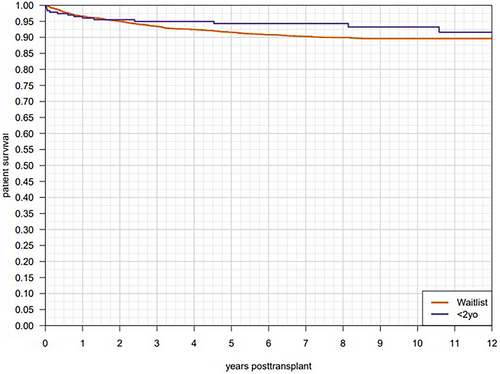

After adjusting for age, gender, race, pretransplant dialysis, blood type, insurance, and transplant center size, we found no difference in patient survival between <2-year decreased-donor recipients and those remaining on the waitlist for posttransplant periods 0–3 months (aHR: 2.05; 95% CI: 0.57, 7.31; p = .27) and 4–12 months (aHR: 0.8; 95% CI: 0.28, 2.29; p = .67). However, the survival was significantly higher for <2-year transplant recipients after 12 months posttransplant (aHR: 0.32; 95% 0.13, 0.78; p = .01; Figure 1).

Table 2 presents the causes of death for <2-year decreased-donor recipients and those on the waitlist until ≥2 years.

3.3 Dialysis-free survival

After adjusting for gender, race, age, blood type, pretransplant dialysis, insurance type, and center size, the 5-year-restricted dialysis-free survival for <2-year deceased-donor transplant recipients was 4.27 years (95% CI: 4.07, 4.46), and that of those who remained on the waitlist until older than 2 years was 3.68 years (95% CI: 3.39, 3.95). The difference in 5-year dialysis-free survival between the two groups was statistically significant at 0.59 years (95% CI: 0.23–0.93).

Table 2 presents the causes of graft loss for <2-year decreased-donor recipients and those on the waitlist until older than 2 years of age.

3.4 eGFR comparison between deceased-donor transplants before age 2 years and deceased-donor transplants after age 2 years

We found no difference in eGFR at 1-year posttransplant between patients who received a deceased-donor transplant before 2 years of age and those who remained on the waitlist and received a transplant after 2 years of age (Median eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2: 92 [71, 117] vs 92 [74, 117]; p = .59).

Similarly, we found no difference in 5-year eGFR between patients receiving a deceased-donor transplant before 2 years of age and those who remained on the waitlist and received a transplant after 2 years of age (Median eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2: 74 [58, 84] vs 68 [55, 84]; p = .12).

3.5 Living-donor transplants

Table 3 compares the characteristics of <2-year living-donor transplant recipients and their corresponding controls. Median age at kidney failure for <2 years living-donor transplant recipients was 8 months (IQR: 3, 16), and the median age at transplant was 19 months (IQR: 16, 21). Seventy-four percent of <2-year living-donor transplant recipients were male, and 91% were white.

| Variables | Recipients transplanted before 2 years (n = 246) | Control/comparison group (n = 766) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age at kidney failure, months Median [IQR] |

8 [3, 16] | 8 [2, 21] |

|

Age at listing, months Median [IQR] |

14 [11, 18] | 17 [13, 20] |

|

Age at transplant, months Median [IQR] |

19 [16, 21] | 28 [23, 36] |

| Transplanted n (%) | 246 (100%) | 642 (84%) |

|

Gender n (%) Male |

183 (74%) | 529 (69%) |

|

Weight at transplant, kg Median [IQR] |

10.8 [9.8, 12.1] | 12.6 [11.0, 14.7] |

| Race n (%) | ||

| Asian | 6 (2%) | 38 (5%) |

| Black | 14 (6%) | 111 (14%) |

| Multi-racial | 3 (1%) | 15 (2%) |

| Native | 0 (0%) | 9 (1%) |

| Pacific | 0 (0%) | 6 (1%) |

| White | 223 (91%) | 587 (77%) |

| Pretransplant dialysis n (%) | ||

| Yes | 173 (70%) | 508 (66%) |

| Donor source n (%) | ||

| Living | 246 (100%) | 166 (26%) |

| Deceased | 0 (0%) | 476 (74%) |

|

Warm ischemia time, min Median [IQR] |

31 [23, 38] | 37 [27, 47] |

| Delayed graft function n (%) | 9 (4%) | 47 (7%) |

| Cause of kidney failure n (%) | ||

| CAKUT | 100 (40.7) | 329 (43.0) |

| Cortical necrosis | 8 (3.3) | 20 (2.6) |

| Cystic kidney | 24 (9.8) | 79 (10.3) |

| GN | 3 (1.2) | 3 (0.4) |

| HUS | 1 (0.4) | 11 (1.4) |

| Malignancy | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Nephrotic | 1 (0.4) | 6 (0.8) |

| Oxalate | 2 (0.8) | 14 (1.8) |

| Other | 101 (41.1) | 280 (36.6) |

| Cause of death n (%) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 0 (0.0) | 7 (10.8) |

| Cerebrovascular | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (14.3) | 2 (3.1) |

| Infection | 2 (28.6) | 11 (16.9) |

| Malignancy | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) |

| Organ failure | 4 (57.1) | 13 (20.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 15 (23.1) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 13 (20.0) |

| Cause of graft loss n (%) | ||

| Chronic infection | 16 (53.3) | 42 (45.7) |

| Infection | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.3) |

| Other | 6 (20.0) | 18 (19.6) |

| Primary non-function | 1 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) |

| Recurrent disease | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.4) |

| Rejection/hyper-acute rejection | 4 (13.3) | 11 (12.0) |

| Surgical/urological complication | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Thrombosis | 3 (10.0) | 9 (9.8) |

3.6 Living-donor transplants before age 2 years versus remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years

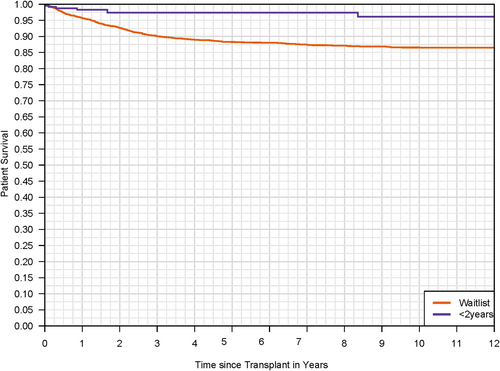

After adjusting for age, gender, race, pretransplant dialysis, blood type, insurance, and transplant center size, we found no difference in patient survival between <2-year living-donor transplant recipients and those remaining on the waitlist until older for posttransplant periods 0–3 months (aHR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.21–5.08; p = .96) and 3–12 months (aHR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.09–1.81; p = .24). However, <2-year living-donor transplant recipients showed a significantly higher patient survival after 12 months posttransplant (aHR: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.06–0.73; p = .01; Figure 2).

Table 3 presents the causes of death for <2-year living-donor recipients and those on the waitlist until ≥2 years.

3.7 Dialysis-free survival

After adjusting for covariates, the 5-year-restricted dialysis-free survival for <2-year living-donor recipients was 4.69 (95% CI: 4.53–4.83) years, while that of patients on the waitlist until ≥2 years was 2.85 (95% CI: 2.47–3.34) years. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant at 1.84 (95% CI: 1.31–2.25) years.

Table 3 presents the causes of graft loss for <2-year living-donor recipients and those on the waitlist until.

3.8 eGFR comparison between living-donor transplants before age 2 years and living-donor transplants after 2 age years

We found no difference in eGFR at 1-year posttransplant between patients who received a living-donor transplant before 2 years of age and those who remained on the waitlist and received a transplant after 2 years of age (Median eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2:92 [76, 121] vs 92 [72, 114]; p = .16).

Similarly, we found no difference in eGFR at 5-years posttransplant between patients receiving a living-donor transplant before 2 years of age and those who remained on the waitlist and received a transplant after 2 years of age (Median eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2: 69 [57, 83] vs 70 [56, 86]; p = .53).

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first population-based study that evaluates the survival benefit of early transplantation in children <2 years of age compared with the remaining on the waiting list until ≥2 years. We found similar patient survival rates between patients transplanted before the age of 2 years and those who remained on the waiting list until ≥2 years for 0–3 and 4–12 months posttransplant. However, we found a significantly higher patient survival after 12 months posttransplant in patients transplanted before 2 years of age, irrespective of the donor source. Furthermore, we found a significantly higher 5-year-restricted dialysis-free survival in children with a living- or deceased-donor transplant before age 2 years versus those remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years.

Kidney transplant outcomes were dismal in the 1970s for children <2 years of age, with a 2-year graft survival of only 17%.13 However, the outcomes improved with growing surgical expertise and newer immunosuppressive agents in subsequent decades, at least at some centers. A retrospective report of 79 infants transplanted at the University of Minnesota between 1965 and 1989 documented a 5-year graft survival of 73% for the transplants performed after 1983.14 Similarly, another study of 136 children <2 years of age, transplanted at the University of Minnesota between 1984 and 2014, reported favorable outcomes with a 5-year death-censored graft survival rate of 81% and patient survival of 96%.15 However, kidney transplant outcomes for children <2 years may not be the same at centers with lower volumes. A smaller retrospective study of 21 children <2 years of age, transplanted between 1980 and 1990, reported lower patient survival in <2-year deceased-donor transplant recipients compared with those ≥2 years at the time of transplant (70% vs 93%; p = .05).16 Our population-based study overcomes center-specific limitations of earlier studies, adjusting the analyses for center size. Given the rarity of kidney failure in infants, it is conceivable that transplant centers struggle to maintain the expertise needed to meet the unique surgical and medical transplant needs of children <2 years of age. However, the benefits of early transplantation call for strategies to develop and maintain the surgical expertise for this age group.

Kidney transplant recipients <2 years of age are at risk of technical and surgical complications, including graft thrombosis and ureteral leak.15 The concerns about early graft loss and the fear of penalty dissuade centers from transplanting children <2 years of age. A retrospective study of 4394 pediatric kidney transplants performed between 1987 and 1995 demonstrated an association between young recipient age and graft thrombosis.17 We found graft thrombosis to be the cause of graft loss in 10–16% of transplants performed before 2 years of age, a rate similar to that in the transplants performed in waitlist controls after 2 years of age. The risk of graft thrombosis may be mitigated with improved attention to perioperative fluid management, pretransplant thrombotic risk factor evaluation, and posttransplant risk mitigation with anticoagulation therapy in select cases. A retrospective study of 136 transplants in children <2 years of age showed an improvement in the incidence of graft thrombosis from 7% to 3% between 1984–1993 and 2004–2014.15 In addition, ureteral leak was observed in only 9 (6.6%) patients.15 Considering a potentially decreasing risk of graft thrombosis and a survival benefit associated with the transplant before age 2 years, one may argue that technical challenges should not be a deterrent to early transplantation.

Children transplanted before age 2 years spent considerably less time on dialysis during a 5-year follow-up period compared with those who waited until ≥2 years. Although a life-saving therapy, children on dialysis have substantially poor growth and inferior neurocognitive outcomes compared with those with a functioning transplant. The delay in transplant may adversely affect cognitive development in children.18 A retrospective study of 15 children transplanted at a mean age of 2.8 (1.3) year found an inverse correlation between the dialysis duration and global intelligence quotient. The study also found significantly higher global IQ in patients with a preemptive transplant or a dialysis duration of <3 months compared with those with dialysis for >3 months.19 A delay in transplantation may also compromise the catch-up growth potential for young children. The 2018 NAPRTCS report showed significant posttransplant improvement in height z scores in infants and preschool children only.20 Furthermore, pretransplant dialysis may jeopardize graft survival in infants and toddlers. A retrospective study of a French national cohort of 224 children <2 years of age with data in Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (REIN) registry found prolonged pretransplant dialysis duration to be a risk factor for graft loss in children <2 years of age.21 Taken together, these data support minimizing dialysis exposure and expediting a kidney transplant for children <2 years, particularly for those with no reason for the delay other than their small size.

As shown by the Australian and European study, less than one-fifth of children with kidney failure onset during the first month of life receive transplant before age 2 years.5 Our study shows similar trends in the United States. Although 1217 patients were waitlisted before age 2 years, only 484 (39.7%) candidates received a kidney transplant before 2 years of age. The relatively higher transplantation rate in children <2 years of age in our cohort could be due to a selection bias, as infants with kidney failure not waitlisted were not included in this study. Children <2 years constituted only 5.5% of pediatric transplants in the 2018 NAPRTCS cohort, corroborating the low transplant rates in this age group.20 The low transplant rates are even more concerning considering that pretransplant mortality is the highest among infants in the United States.2-4 Our findings challenge the prudence of delaying the transplant and call for a paradigm shift to promote early transplantation in infants and toddlers.

Our study had a few limitations. One, we could be overestimating the transplantation rate in children <2 years of age due to selection bias as children with kidney failure not waitlisted were not included. Second, we could not determine the true incidence of surgical/urological complications and graft thrombosis, as these data are captured by SRTR only if they result in graft loss. Due to the small number of graft loss events due to thrombosis, we could not analyze temporal changes in graft loss due to thrombosis. The strengths of our study include its population-based study design. The mandatory nature of data collection by SRTR makes our study generalizable to all children <2 years who are waitlisted for a kidney transplant in the United States.

To conclude, kidney transplantation in children before 2 years of age is associated with a survival benefit and reduced dialysis exposure compared with remaining on the waitlist until ≥2 years. We found no evidence of increased early posttransplant mortality. Based on our results, we are of the opinion that children should be transplanted as soon as possible when the medical and surgical risks have been minimized and an arbitrary “optimal age” should not be a criteria for transplantation. Since it may be difficult for centers with low volumes to maintain the surgical expertise required for transplanting children <2 years of age, we suggest maintaining this expertise at large transplant centers through a referral system. Children younger than 2 years should be referred to centers with the required transplant expertise for a timely transplant to optimize patient survival, physical growth, and neurocognitive development. Additional studies are required to investigate the risk factors for technical complications and strategies to alleviate those risks.

DISCLOSURE

The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute (HHRI) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data for this study are available in SRTR. The data may be requested from SRTR.