Effective treatment of diabetes, improved quality of life and accelerated cognitive development after pancreas transplantation in a child with type 1 diabetes and allergy to manufactured insulin preparations

Abstract

Background

Insulin hypersensitivity reactions are rare but serious and significantly affect the treatment of diabetes in children.

Methods

A 13-year-old girl with type 1 diabetes, hypoglycemic unawareness, and treatment refractory allergy to available insulin preparations underwent a solitary pancreas transplant. Before the pancreas transplantation, she was receiving a continuous subcutaneous infusion of rapid-acting insulin with an increasing need for antihistamines and steroids, negatively impacting her cognitive and social development. Her diabetes was poorly controlled, and her quality of life was progressively worsening.

Results

Following the transplant, she recovered well from surgery and achieved euglycemia without needing exogenous insulin. She had two biopsy proven episodes of acute cellular rejection, successfully treated. Her cognitive development also accelerated. Notable improvement was noted both in her personal quality of life and her family's overall well-being.

Conclusions

This is the youngest pancreas transplant recipient with over 1-year graft survival reported in the literature. Pancreas transplant alone in a teenager without indications for kidney transplantation could be considered a last resort treatment for diabetes when continuing insulin therapy presents a high level of morbidity. A pancreas transplant is a feasible treatment modality for patients with refractory insulin allergy.

Abbreviations

-

- ACR

-

- acute cellular rejection

-

- ANC

-

- absolute neutrophil count

-

- ATG

-

- thymoglobulin

-

- AZA

-

- azathioprine

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CMV

-

- cytomegalovirus

-

- CPR

-

- cardiopulmonary resuscitation

-

- cPRA

-

- calculated panel-reactive antibody

-

- CT

-

- computer tomography

-

- DSA

-

- donor specific antibody

-

- EBV

-

- epstein–barr virus

-

- HbA1c

-

- hemoglobin A1c

-

- HLA

-

- human leucocyte antigen

-

- MMF

-

- mycophenolate mofetil

-

- MFI

-

- mean fluorescence intensity

-

- PCP

-

- pneumocystis pneumonia

-

- PCR

-

- polymerase chain reaction

-

- PTA

-

- pancreas transplant alone

-

- QoL

-

- quality of life

-

- SPK

-

- simultaneous pancreas and kidney

-

- WCC

-

- white cell count

1 INTRODUCTION

Pancreas transplantation in children is uncommon. Limited case series describe simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplants (SPK) in teenagers with type 1 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. In the absence of indications for kidney transplantation, pancreas transplant alone (PTA) can be considered for patients in whom benefits from improved glycemia control would justify undergoing major surgery and the burden of lifelong immunosuppression.1

Pancreas transplant alone was reported as a successful treatment of diabetes complicated with insulin allergy in adults in 1998.2 In the modern era, there are desensitization strategies for antibody-mediated insulin allergy, but none of these were applicable for our patient.3

The youngest documented recipient of PTA was 11 years old but lost the graft within 6 months. Here we present a case of a 13-year-old girl with an allergy to manufactured insulin preparations who received a pancreatic transplant.

2 PATIENT AND METHODS

A 12-year-old girl with type 1 diabetes diagnosed at 4 was referred to the University of Minnesota for pancreas transplantation. She had hypersensitivity reactions to preservatives present in insulin preparations that ranged in severity from simple urticaria to life-threatening anaphylaxis. She developed a skin rash and respiratory distress with her first dose of glargine insulin and had a similar reaction after glulisine. Polysorbate 20 found in these two insulin formulations was thought to be the trigger. Drug hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis were reported for several biotherapeutics containing polysorbates. Polysorbate 80 is present in inhaled insulin.4-7

She also developed immediate and delayed hypersensitivities to subcutaneous insulins not containing polysorbates. The skin rash in response to the insulin pump content was initially noted at the injection site but, with time, appeared all over her body. The skin test for purified insulin lispro was negative. Metacresol is a preservative present in the lispro solution. Hypersensitivity reactions to insulin preparations with metacresol as an excipient were described before in adults and children.8 A skin test with purified metacresol showed a delayed response.

She continued to experience glycemic lability with prolonged hyper and hypoglycemia events depside intensive medical management. Glycemic control was erratic, blood glucose ranged from 40 to 500, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 7.6% (60 mmol/mol). Her basal insulin requirements via pump were high (1.23 u/kg/day) for her age, even with a low carbohydrate diet. She had hypoglycemic unawareness although not requiring hospital admission.

Even with topical steroids and multiple antihistamines, she struggled with localized hives, generalized painful maculopapular rashes, and dermatographism. She developed chronic abdominal pain and hyperalgesia all over her body, thought to be secondary to histamine release.

The increasing need for antihistamines significantly affected her quality of life. The formal neuropsychological assessment showed that she met her motor and language milestones, but her social development was of concern. Her ability to recall verbal information after the passage of time ranged from below average to average.

At the time of referral, her everyday functioning was grossly affected by somnolence, and therefore we expedited her transplant evaluation. She was listed for PTA within 2 months and a suitable donor became available 5 months later. It was a 23-year-old brain-dead male with a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 29 kg/m2 who died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. HLA mismatch was 2-2-2.

The pancreas was placed intraperitoneally. The portal vein was anastomosed to the vena cava and the duodenum to the jejunum for enteric exocrine drainage. Cold ischemia time was 6 h and 17 min, and warm ischemia time was 30 min.

We followed our standard immunosuppression protocol. Induction was with 1.25 mg/kg Thymoglobulin (ATG) preceded by 500 mg of methylprednisolone. She received seven doses of ATG. Intravenous mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and octreotide were given intraoperatively. Piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole were used for perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis. Initial maintenance immunosuppression was 750 mg MMF and 2 mg tacrolimus twice daily, with a target tacrolimus level of 8–10 ng/ml. MMF was then switched to mycophenolic acid (540 mg twice daily). Valganciclovir and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were used for cytomegalovirus (CMV) and pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis.

She was on intravenous insulin immediately following surgery, with an infusion rate of 0.02 u/kg/h, adjusted to maintain blood sugar levels of 80–130 mg/dl. It was discontinued on postoperative day one.

We initiated postoperative anticoagulation as per center protocol with fixed rate heparin infusion for 5 days and lifelong administration of 325 mg aspirin.

We routinely administer intravenous octreotide to ameliorate post-reperfusion graft pancreatitis, but it was discontinued due flushing and severe nausea.

3 RESULTS

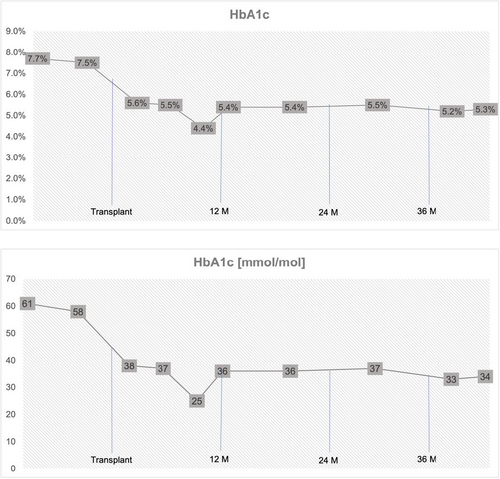

With the pancreatic transplant, adequate glycemic control was achieved (Figure 1). Discontinuation of insulin allowed for complete resolution of hypersensitivity reactions. During an early postoperative period, our patient experience a series of minor complications, but these did not significantly affect her outcome.

3.1 Early postoperative period

Having evidence of satisfactory endocrine function, we also monitor lipase levels to detect any insult to the pancreatic graft. During the early postoperative period, lipase levels fluctuated. This triggered undertaking imaging studies, diagnostic interventions, and initiating additional treatment.

Computer tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed on postoperative day 3. It showed uniformly perfused graft and non-occlusive thrombus in the splenic vein along the body of the pancreas. This thrombus was managed by increasing the rate of intravenous heparin and initiation of warfarin.

Because of the possibility of graft pancreatitis and rejection contributing to the rising lipase, subcutaneous octreotide was administrated, and the dose of mycophenolic acid was increased to 720 mg twice daily.

Follow-up CT demonstrated significant improvement in the splenic vein thrombosis. Biopsy on postoperative day 12 did not show rejection. Immunofluorescence staining was negative for C4d and C3d. A low level of de novo DSA anti-HLA Cw9 was detected by the Luminex technique with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 843.

In the CT on postoperative day 19, a fat stranding was noted around the medial aspect of the body and tail and another two doses of subcutaneous octreotide were given. Luminex on postoperative day 23 showed anti-HLA antibody Cw9 (847MFI). We treated the presumptive rejection with steroids, but lipase did not improve. She received two doses of 500 mg of methylprednisolone and another two of 100 mg. The steroid taper was 20 mg every other day.

The biopsy on postoperative day 26 showed moderate acute cellular rejection. Immunofluorescence staining for C4d and C3d was inadequate. Luminex revealed an anti-HLA Cw9 antibody (514 MFI) and anti-HLA DQB7 DSA with MFI of 1054. She received 100 mg of ATG with 100 mg methylprednisolone and 30 mg of alemtuzumab the next day. Tacrolimus was changed to a sublingual form. Biopsy findings and Luminex results are summarized in the table (Table 1).

| Time after transplant | Biopsy results | Luminex results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejection on biopsy | C4d and C3d | DSA | MFI | |

| POD 12 | No ACR | Negative | Anti-HLA Cw9 | 843 |

| POD 26 | Moderate ACR | Inadequate sample |

Anti-HLA Cw9 Anti-HLA DQB7 |

514 1054 |

| M 2 | Resolving ACR | C4d positive (5%) | None | |

| M 6 | No ACR | Negative | None | |

| M 14 | Mild to moderate ACR | Negative | Anti-HLA DQB5 | 569 |

| M 15 | Resolving rejection | Negative | None | |

- Abbreviations: 14 M, 14 months post-transplant; 15 M, 15 months post-transplant; 2 M, 2 months post-transplant; 6 M, 6 months post-transplant; ACR, acute cellular rejection; DSA, donor-specific antibody; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; POD, post-operative day.

3.2 Further rejection complications

The patient was discharged on postoperative day 33 and readmitted 2 weeks later for a scheduled pancreas biopsy, which showed resolving rejection with scattered T-cells in the parenchyma but no definitive infiltration or clustering of T-cells around the islets. Immunofluorescence showed focal interacinar capillary staining for C4d (5%). No DSA was detected 3 weeks after the repeated biopsy (Table 1). Lipase levels normalized 3 months after the transplant.

During the first year, the immunosuppression regime required frequent adjustments due to side effects and further concerns for rejection. Because of ongoing gastrointestinal disturbances, mycophenolic acid was switched to azathioprine (AZA), which was soon discontinued because of persistent neutropenia. The patient was started on everolimus with a goal of 2–3 ng/ml and maintained on 5 mg prednisolone.

A protocol biopsy performed at 6 months showed no evidence of rejection, and there was no detectable capillary staining for C4d and C3d (Table 1).

Fourteen months after the transplant, lipase and blood glucose started trending up. She was readmitted for a biopsy, which showed moderate acute cellular rejection and was treated it with five doses of ATG. Luminex revealed a low level of anti-HLA DQB5 antibody (569 MFI). Follow-up biopsy showed resolving rejection (Table 1).

3.3 Infectious complications

The patient experienced early infectious complications witch hospital admissions. Five months after the transplant, she became neutropenic and required scheduled filgrastim. Extensive bone morrow suppression workup was undertaken and concluded with a diagnosis of autoimmune neutropenia. She had three admissions with fever to her local hospital. Symptoms resolved with antibiotics and improved absolute neutrophil count (ANC) from filgrastim treatment. The likely causes were urinary tract and upper respiratory tract infections.

During the treatment of her second episode of rejection, she developed a fever with a cough, and a chest CT showed pulmonary infiltrates. She was treated with azithromycin, micafungin, and piperacillin/tazobactam, discharged after completion of anti-rejection treatment, but then readmitted the next day with a fever. Chest CT showed mildly worsening lung infiltrates, and antibiotic coverage was expanded to vancomycin. She improved clinically, and a follow-up CT showed decreased consolidations with no bronchiectasis. Pulmonary function tests were within normal limits.

She is under CMV, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), and BK virus surveillance. CMV was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 7 months after her transplant, with a peak level of 6750 copies/ml. Following treatment, this declined to an undetectable level within a month. She was treated with 900 mg of valganciclovir daily for 10 weeks, which was decreased to 450 mg daily due to neutropenia. A year after the transplant, CMV was again detected. The valganciclovir dose was increased to 900 mg daily, with a resolution of the viremia within a month. She continues on Valganciclovir 450 mg daily. She has not had EBV viremia to date. BK was detected in small amounts and not quantified.

3.4 Current status

Her current immunosuppression regimen comprises everolimus (goal 3–5 ng/ml), tacrolimus (goal 6–8 mg), and prednisolone 7.5 mg daily (increased after the second episode of rejection). She receives filgrastim to keep her absolute neutrophil count (ANC) above 1500. She has normal kidney function with a glomerular filtration rate adequate for her age. Her C-peptide is within normal limits. Current HbA1c is 5.3% (34 mmol/mol), with a nadir of 4.4% (25 mmol/mol) before the most recent rejection episode.

3.5 Quality of life (QoL) improvement

We contacted our patient and her family to retrospectively rate and compare pre- and post-transplant QoL. We used The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: Adolescent AQoL - 6D Simplified questionnaire developed by the Centre for Health Economics at MONASH University in Australia.10 Results are presented in Table 2.

| Area questioned | At the time of listing for the transplant | At the most recent follow up | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical ability | 8 | 20 | 4–22 |

| Social and family relationships | 7 | 12 | 3–13 |

| Mental health | 16 | 20 | 4–20 |

| Coping | 5 | 13 | 3–15 |

| Not being in pain | 3 | 11 | 3–13 |

| Vision, hearing and communication | 10 | 13 | 3–16 |

| Total | 49 | 89 | 20–99 |

The patient reported significantly improved overall well-being, physical ability, social and family relationships, mental health, coping, and pain. She is satisfied with her relationships with family and friends. Before the transplant, she felt indifferent about making friends, and some aspects of her family life were affected. She was not able to involve in any group activities. Now, only occasionally, she is restricted by health-related issues.

4 DISCUSSION

Experience of pancreas transplantation in children is minimal due to concerns for subjecting them to surgical complications and side effects of immunosuppression. It should only be considered when there are no less risky alternatives available. Our patient suffered both from diabetic complications and side effects of medical treatment of her hypersensitivity to manufactured insulin preparations. PTA was a last resort for her and was undertaken after medical treatment continued to adversely affect her physical and cognitive development and quality of life. The surgical technique and the immunosuppression protocol were based on our institution's extensive experience in adult pancreas transplantation. We were also aware of cases of pancreas transplantation in teenagers reported in the literature.

Six patients younger than 18 underwent pancreas transplants at our institution between 1966 and 2000: two SPK (12 and 14 years old) and four PTA (older than 15). The two SPK recipients had functioning allografts at 5 years post-transplant. One PTA patient had a functioning allograft at 4 years follow-up, while the other three failed within less than 6 months.11, 12 Six more SPK teenage recipients (13–16 years old) are reported in the literature, three from the US, two from the UK, and one from Belgium.13

During the transplant evaluation of our patient, pancreatic islets were also considered. The multidisciplinary team agreed it would not be a good option for a patient requiring prompt and complete discontinuation of insulin.

Pancreas transplantation outcomes significantly improved over the last decade with a low incidence of early graft losses and good long-term survival. The previous year's program-reported early graft failure for PTA was 7.3%, 5-year mortality was 11.7%, and 10-year mortality was 20.7%.14 The long-term mortality data reflect cardiovascular comorbidity. Transplanting younger patients with no comorbidities and less disease burden should positively affect their long-term survival.

Treatment of complications experienced by our patient was as per adult protocol but modified and tailored to her young age. Specifically, we avoided too much ATG because loading with high doses of ATG has been associated with increased malignancy rates. It was the rationale behind administrating alemtuzumab. The reason for surveillance biopsies was to optimize immunosuppression long-term and detect early signs of failing graft. She might be a candidate for a pancreatic islets transplant in the future with the partial function of her pancreatic allograft.

Pancreatic transplant recipients are routinely anticoagulated.9 Splenic vein thrombosis is not an unusual CT finding, but the impaired graft function is rarely attributed to it. Treatment is not protocolized. Follow-up images help decide the length of the therapy.

Recipients of pancreas transplantation due to the use of T-cell-depleting antibodies are at higher risk of virus re-activation and fungal infection. In adults, we use a short-in-duration, systemic antifungal prophylaxis strategy, which we did in this case. Infectious risks remain a concern, given her immunosuppressed status and prolonged neutropenia. Fortunately, her subsequent bone marrow biopsy showed improvement, and she remains infection-free with ANC > 1500.

Based on PTA graft survival expectancy derived from data collected at our institution, we anticipate this pancreas to function for more than 10 years (PTA half-live in the current immunosuppression era is 10 years).15

The freedom from diabetes has been life-changing for our patient. The neuropsychological evaluation revealed that she no longer complained of ongoing pain affecting her everyday activities. Her sleep patterns were within normal limits, and her anxiety resolved. Her cognitive and social development accelerated. She creates artwork and has returned to in-person schooling. She does volunteer work with animals and has traveled abroad with her family.

A successful outcome of our recipient can be attributed to a combination of favorable patient factors, planning, and good family cooperation at every stage of the process. She received care from a multidisciplinary team comprised of transplant surgeons, pediatric endocrinologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, intensivists, pharmacists, and pre- and post-transplant coordinators. She was offered a high-quality organ recovered locally, which helped minimize cold ischemia time. Following her return home, local pediatricians communicated concerns directly to our team. The family was willing and able to promptly travel back to our transplant center when rejection was suspected.

In summary, we report a case of PTA in a teenager with graft survival exceeding 1 year. We do not advocate for pancreas transplantation in children as front-line therapy but rather to be merit consideration for a highly selected group of patients who can be appropriately evaluated and treated in experienced high-volume transplant centers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: AA wrote the manuscript; AA, KR, and TM collected the data; MB and RK edited the draft and supervised the writing of the manuscript; RK conceptualized the project and designed the study. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to acknowledge input from the patient's parents. They contributed to the manuscript by providing updated information on their child's health issues and encouraging raising awareness of her case within the medical community.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.