Experience of ethical dilemmas among professionals working in pediatric transplantation: An international survey

Abstract

Background

Professionals working in pediatric transplantation commonly encounter complex ethical dilemmas. Most ethical research in transplantation is related to adult practice. We aimed to gain insight into ethical issues faced by transplant professionals when dealing with pediatric transplant recipients.

Methods

A two-stage study was designed; the first part was a questionnaire completed by 190 (80%) members of the International Pediatric Transplant Association (IPTA) from over 30 different countries. This was followed by a multidisciplinary focus group that explored the preliminary data of the survey.

Results

A total of 38% (56 of 149) respondents of the questionnaire had experienced an ethical issue between 2016 and 2018. Surgeons were more likely to have encountered an ethical issue as compared with physicians (60% vs. 35.7%, p = .035). Clinicians from Europe were more likely to have experienced an ethical issue in living organ donation compared with those from North America (78.9% vs. 52.5%, p = .005), with common ethical concerns being psychosocial evaluation and follow-up care of donors. The focus group highlighted the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to ethical issues.

Conclusion

The results of this study can direct future research into pediatric transplantation ethics with the aim of producing educational resources, policies, and ethical guidelines.

Abbreviations

-

- IPTA

-

- International Pediatric Transplant Association

-

- BTS

-

- British Transplantation Society

-

- GAfREC

-

- governance arrangements for research ethics committees

-

- MDT

-

- multidisciplinary team

1 INTRODUCTION

With solid organ transplantation now being the gold standard treatment for end-stage organ disease, the possibility of successful transplantation is among the most important interventions within modern medicine. The process of obtaining and fairly allocating organs has led to the rise of complex ethical dilemmas.1-3 The occurrence of these ethical issues is mostly an unavoidable consequence of the pervasive challenge of organ shortage.4 Ethical issues are likely to remain commonplace in transplantation with the demand for transplantable organs ever-increasing. This is due to higher incidence of end-stage organ disease,5 increasing global transplant rates, and advancement of medical technology, allowing for increasingly complex patients to receive an organ.6, 7 Despite implementation of numerous policies to increase the supply of organs required, the global demand for organs still far exceeds the supply.1, 8

Ethical issues are defined as issues being related to beliefs about what is morally right and wrong, as such there are no right or wrong answers but different point of views.9 Bioethics can be a useful tool for transplant professionals and policymakers to help tackle and navigate complex ethical dilemmas encountered in transplantation.10 The ethical implications of transplantation are extremely important to consider in both adult and pediatric care.

While encountering ethical issues within adult transplantation is frequent problem in many healthcare systems worldwide, there are few data available into the ethics of pediatric organ transplantation. Although some adult data mention pediatric care, there is a lack of research tailored to ethical issues that may arise in pediatric transplantation. It is important to consider that pediatric patients account for 10% of all organ transplantations;11 therefore, this area of medicine needs further exploration.

While research surrounding adult transplantation ethics can be useful for ascertaining pediatric transplant professionals' experiences for some ethical issues, the data cannot always be applied to pediatric recipients and the professionals that care for them. There are several ethical issues that are specific to pediatric transplantation that require a specialized ethical approach.

Identifying how the type of ethical concerns and dilemmas differ between different professional roles and countries can lead to a better understanding of cultural attitudes that affect patient experiences and expectations with transplantation. The need for identifying cultural values is becoming increasingly important in the face of globalization of health care, resulting in more individuals traveling abroad for access to transplants.12, 13 The reasons for the differences of ethical issues vary widely between countries, as cultural attitudes and differing medical policies influence the type of issues experienced. Ethical issues relating to deceased organ donation are experienced less in countries such as Japan and Germany, as they have limited or no deceased donor programmes due to cultural beliefs and legal frameworks.14-17 In the United Kingdom, however, donation after circulatory death is considered ethically acceptable.18 These differences in medical policy and culture can result in ethical issues such as organ trafficking and lenient psychosocial evaluation of living donors to be encountered more frequently in certain countries. A declaration on organ trafficking and transplant tourism highlighted the importance of international collaboration to prevent ethical issues from occurring and improving transplant practices.19

The aim of our study was to identify the prevalence of specific ethical issues and the areas of practice in which they are encountered by medical professionals working in pediatric transplantation globally. We aimed at understanding differences in experience between different transplant professionals and whether any differences were experienced due to geographical variation in practice. This study also aimed to determine which of these issues were most important for medical authorities to address.

2 METHODS

An international questionnaire was formulated to identify the areas of practice in which pediatric transplant professionals had experienced ethical issues or dilemmas. A focus group was then conducted to explore the themes in detail.

Ethical approval was not required for either the questionnaire or the focus group as the research was involving healthcare staff as per UK guidelines of the GAfREC.20

The questionnaire was developed on a similar format to a survey on adult transplants conducted by The Transplantation Society (TTS).21 Due to the uniqueness of ethical issues specific to pediatric patients, many of the questions and answer options were reformulated for the questionnaire, by professionals experienced in bioethics. Although ethical dilemmas were not defined as such, the questions were illustrated with examples to make the themes clear. The questionnaire was reviewed and approved by members of the International Pediatric Transplant Association (IPTA) Ethics Committee. A pilot study of this questionnaire was not conducted as the adult survey had already been trialed and validated. The survey was accessible exclusively online and was uploaded to Survey Monkey® for a period of 2 months in early 2018. The questionnaire was available in English and Spanish.

Consent was obtained through a Plain Language Statement (Appendix A). The survey was programmed with a Skip Logic function. This allowed the respondents to skip to a further point in the survey depending on the answer they had given to a previous question resulting in participants with limited experiences with ethical issues to complete the survey faster.22

The survey contained 35 questions, which were divided into categories/themes in which ethical issues are encountered within transplantation medicine. These included living organ donation, deceased organ donation, transplantation and allocation, organ trading, transplant tourism, incentives and healthcare funding, and professional interactions.

The questionnaire (Appendix B) was disseminated to all IPTA members via email. In total, three emails were sent out to all IPTA members. Individual transplant centers were contacted for further dissemination among pediatric transplant professionals.

Once the results were received, a 10-member, multi-professional focus group was conducted to further explore the themes raised in the survey and to understand the experiences of pediatric transplant professionals. The focus group identified which ethical issues professionals felt are most important to address.

Recruitment for the focus group focused on expert sampling. It consisted of transplant professionals that had at least 10 years of experience within transplantation. The participants for the focus group were recruited through professional connections within the British Transplant Society (BTS). A mixture of professional roles was recruited that were representative of the professional transplant community. The discussion was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Confidentiality and anonymity of those involved was ensured, and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the closed and multiple response sets question data using SPSS version 24.0. Chi-squared test was used to compare different subgroups for region and professional role. The analysis of the focus group involved thematic analysis. The focus group data were analyzed using NVivo (version 11) qualitative data analysis software, allowing for higher quality thematic analysis and organization of the data.23

3 RESULTS

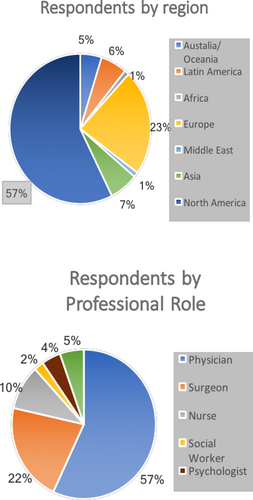

Of 238 active members of the IPTA, 190 (52% women) online questionnaire responses were collected leading to a response rate of 80%, with responses from clinicians working in 30 different countries in the world (Figure 1).

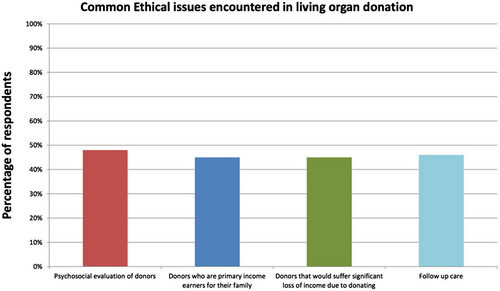

The average experience of respondents working in pediatric transplantation was between 15 and 20 years, with the majority working in kidney transplantation (107 of 181, 59%). The age of respondents was evenly split between 30 and 60 years, (56 of 180, 31%) between 40 and 49 years. Fifty-six (38%) respondents reported that they had experienced an ethical concern or dilemma related to pediatric transplantation. The main themes arising from living and deceased organ donation are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

One hundred and eight (57%) respondents had experienced an ethical concern relating to living organ donation during their careers, with 48% experiencing an ethical issue related to the psychosocial evaluation of transplant candidates (Figure 2). Other common ethical concerns that were encountered centered around the financial stability of the potential donors (Figure 2), either using a donor who is the sole or primary income earner for their family (45%) or donors that would suffer significant financial costs and loss of income because of donating (45%). Issues relating to living donors' follow-up care was also an area of concern for many pediatric transplant professionals, with 46% of professionals experiencing this concern throughout their medical practice.

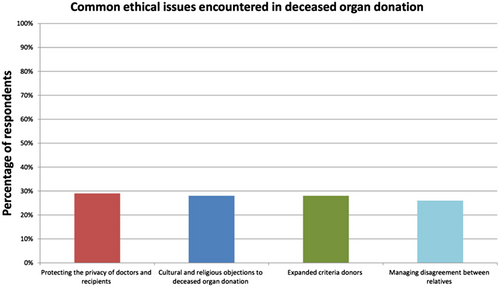

The proportion of pediatric transplant professionals who had experienced an ethical concern or dilemma in deceased donation was reported less when compared with living organ donation (49% vs. 57%).

Frequent themes of ethical concerns were protecting the privacy of doctors and recipients (29%), and cultural and religious objections to deceased organ donation (28%). Expanded criteria donors (28%) and managing disagreement between relatives (26%) when attempting to obtain consent and authorization were also important ethical concerns.

Ethical issues relating to wait-listing recipients received the most positive responses out of any category included in the survey. With 68% of respondents had experienced ethical dilemmas relating to wait-listing, candidate selection and organ allocation. Sixty-nine (63%) respondents identified registering nonadherent patients on the waiting list as a prominent ethical concern, while 55% respondents expressed concerns about whether to wait-list patients with developmental delay.

In terms of deceased donor allocation policies, 60% of respondents identified moral conflicts between allocation outcomes that maximize utility (therapeutic value of a transplant) and those that promote equality (giving all transplant candidates a share of the benefits of transplantation) as the main concern.

Of all professional role subgroups, only physicians and surgeons had large enough sample sizes for valid Chi-squared tests (Figure 1). There was a significant difference between physicians and surgeons' experiences with ethical issues. However, no statistically significant differences were found between the ethical issues faced by surgeons and physicians over the time of their entire careers for both living and deceased organ donation. Surgeons were more likely to experience an ethical concern relating to any aspect of transplantation than physicians: 60% (15/25) versus 36% (25/70) (Chi-squared: χ2 = 4.46, df = 1, p = .04).

In ethical issues relating to living organ donation, 80% (28 of 35) of transplant surgeons compared with 65% (56 of 87) of physicians reported to have had experienced an ethical concern (Chi-squared: χ2 = 2.84, df = 1, p = .09). In ethical issues, relating to deceased organ donation, 55% (16 of 29) of transplant surgeons compared with 52% (42/81) of physicians had experienced an ethical concern (Chi-squared: χ2 = 0.09, df = 1, p = .76).

Pediatric professionals working in Europe were more likely to have experienced an ethical issue in living organ donation compared with those working in North America: 78.9% (30 of 38) versus 52.5% (52 of 99) (Chi-squared: χ2 = 7.98, df = 1, p = .005). 2% of responses were recorded from clinicians working in Africa or the Middle East (Figure 1). In deceased donation, there was no significant difference between the frequency of ethical issues experienced: with 62% (21 of 34) versus 51% (46 of 90) having experienced an ethical issue in Europe and North America, respectively (Chi-squared: χ2 = 1.13, df = 1, p = .288). There was no significant difference in the likelihood of a transplant professional experiencing an ethical issue in any area of transplantation between regions: with 62% (21 of 34) versus 51% (46 of 90) having experienced an ethical issue in Europe and North America respectively (Chi-squared: χ2 = 0.38, df = 1, p = .6; Appendix B).

A total of 2% respondents (3/144) reported that they were satisfied with the activities currently being undertaken by the IPTA in the fields of ethics. In response to what activities IPTA should undertake to address current ethical issues within pediatric transplantation, the development of guidelines for specific ethical issues was the most requested (53%,100 of 189). Development of educational and training resources in clinical ethics (65%; 94 of 144) and presenting reviews and analyses of key ethical issues in transplantation (59%; 85 of 144) were also highly requested. Respondents identified allocation of deceased donor organs (35%; 51 of 146), equity in access to transplantation in developing countries (32%; 46 of 146) and the use of social media for obtaining altruistic donors (33%; 48 of 146) as the most important ethical issues that needed to be addressed by IPTA.

3.1 Focus group

The focus group conducted a month after the survey results were received, consisted of ten participants excluding the moderator and note-taker. There was a mixture of professionals from nine different teaching hospitals in United Kingdom. Two members of the focus group also worked in adult transplantation.

Responses from the survey were discussed as themes. An overarching theme arising from the group discussion was the importance of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach when deciding on how to move forward in an ethical scenario. The group agreed that it would be not suitable for just one individual to make all the decisions on how to proceed in difficult situations and that a team approach should be adopted when dealing with complex scenarios.

Development of specific pediatric guidelines was explored but, concerns were raised around how ethical guidelines could be a box ticking exercise. It was suggested that a guideline could discourage the application of a shared approach when dealing with an ethical dilemma and that this could result in clinicians overlooking important factors that are not mentioned in the guideline.

Many members agreed that having a framework that was not overly prescriptive, on how to approach specific ethical issues would be more useful.

Many of the differences in opinion between professionals centered on the use of monetary incentives and how this is both a problem and a possible solution to several ethical issues faced in transplantation medicine. The exploitation of individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds as organ donors was flagged as a difficult issue to manage. Concerns were expressed around how patients can take advantage of these individuals and claim them as a true altruistic donor and how it was exceedingly difficult to prove. It would be difficult to ascertain if follow-up care to these donors would be provided at all. The focus group unanimously agreed that more needs to be done to help identify donors from low socioeconomic backgrounds and to develop pathways to avoid coercion.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first international survey to identify common ethical concerns that are experienced by pediatric transplantation professionals. This study was also the first to investigate and show statistically significant differences in ethical issues are experienced by pediatric transplant professionals who work in the Europe compared with North America, in living organ donation. The results also indicate that surgeons experience more ethical issues in pediatric transplantation compared with physicians. The multidisciplinary focus group highlighted the importance of a shared approach when attempting to solve these complex ethical issues. The development of resources to support transplantation professionals who encounter ethical dilemmas was highly requested by the multi-professional community. The results of this study add important quantitative and qualitative data to the area of the pediatric transplantation ethics, in which small body of published literature currently exists.

Psychosocial evaluation was identified as a common ethical issue experienced in living organ donation. A similar international survey on transplantation ethics in adults identified psychosocial evaluation of transplant candidates as a common ethical concern,23 suggesting that assessing the psychological wellbeing and social factors surrounding a patient is a universal problem in transplantation medicine. This issue can be particularly challenging for clinicians as they are under intense pressures to ensure that good-quality organs are put to the best use. Poor psychological health and lack of social support can result in nonadherence and morbidities in patients which ultimately leads to poorer transplant survival outcomes and mortality.24

Nonadherence, especially listening nonadherent individuals, was identified as a common ethical issue. Nonadherence is a significant challenge in the pediatric population, with demonstrated links to adverse outcomes post-transplantation.24, 25 The results of this survey conform to the popular consensus that discussion of ethical issues in pediatric transplantation should consider the complexity of psychological health in children.26

Protecting the privacy of deceased donors was also highlighted as an important issue. Recently organizational efforts have been made to try and standardize the way transplant centers share information with one another regarding organ recipients and donors, as previous communicating between centers has been inconsistent and at times unethical.27

Pediatric professionals working in Europe were more likely to have experienced an ethical issue in living organ donation compared with those working in North America. A significant difference was only found in ethical issues related to living organ donation and not deceased donation. This difference can possibly be explained by organ allocation policy changes in North America in 2013.28 The allocation policy (Share35) was introduced in North America to reduce wait-listing times for deceased kidney donation in pediatric patients.29 This policy resulted in a paradigm shift away from living donation in the United States and could explain the reduction in ethical issues faced in this area of transplantation. It is important to consider that transplantation policies in Europe are more variable as many individual countries have independent transplant systems. Further research should attempt to identify whether policy changes that decrease living organ transplants can lead to a reduction in the ethical issues faced in living organ donation, and whether European transplantation systems should adopt policies such as Share 35 adopted in North America.

Surgeons experienced more ethical concerns relating to any area of transplantation than physicians. Surprisingly, this difference is somewhat contradicted by the fact that there were no significant differences in ethical issues experienced between these roles in living or deceased organ donation. One possible explanation for the difference in ethical issues experienced between surgeons and physicians could be the increasing complexity of possible transplant candidates.6, 7 The improvements in immunosuppression, post-transplant care and surgical techniques has lowered the threshold for accepting transplant recipients, leading to more ethical issues in living organ donation being encountered within recent years. These results suggest that some professional roles are more prone to encountering ethical issues. Further research is needed to investigate the reasons behind these differences. A recent systematic literature review on the roles of healthcare professionals working in transplantation and donation also highlighted the need for research to examine how professional roles can impact the donation and transplantation process.30

Only three respondents were reported to be satisfied with the activities that IPTA have undertaken in the fields of pediatric transplant ethics. The results suggest that significant improvements are required in the ways that healthcare systems and medical authorities provide support for pediatric transplant professionals who encounter ethical issues. The development of guidelines for specific ethical issues was the most requested in the survey and was discussed at the focus group. However, the focus group agreed that the guidelines should not be overly prescriptive and implement a multidisciplinary approach to be an effective aid for clinicians.

A major strength of this study was the large sample size of the questionnaire. Despite this, an entirely representative sample of the international transplant community was not obtained. Only 2% of responses were recorded from clinicians working in Africa or the Middle East and the questionnaire was available in only two languages. This would have made participation difficult due to underrepresentation of professionals from areas where these languages are not spoken. Ethical dilemmas were, in some questions, not clearly defined, which could have introduced bias as to the understanding of the questions. Specific examples of these dilemmas, as a part of the question ligand, might have helped mitigate this issue, but we felt best to limit the length of the questionnaire to encourage better response rate. We also felt that this in itself might introduce bias as the questionnaire might not then remain open ended. These reasons could explain the overall low percentage of professionals reported to have experienced an ethical dilemma.

The make-up and the limited focus group sessions could have introduced colleague bias as well. However, due to the small cohort of UK pediatric transplant community, this bias is difficult to avoid. It is also important to understand that this focus group was conducted with adult and pediatric transplantation professionals working in the United Kingdom and while many participants had experience working in different countries, this sample did not truly represent the international transplant community. Despite the limitations on achieving the best representation for the focus group, we believe that it allowed for a better understanding and a deeper dive into the themes uncovered in the questionnaire. The discussions regarding the development of guidelines and issues around financial compensation could not have been better understood, if the focus group had not taken place. For that reason, we feel that the focus group adds value to the study.

Despite the limitations of this project, the results of both the international survey and multi-professional focus groups have important implications for future practice in pediatric transplantation. Ethical framework specific to pediatric transplantation should be produced with a focus on the prevalent issues identified in this study, such as psychosocial evaluation, wait-listing nonadherent patients and follow-up care of donors. When developing this framework, medical authorities must incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and not be overly prescriptive to the point that clinicians become formulaic in the way they handle ethical issues, the framework must promote critical thinking combined with discussion among other colleagues.

European countries can look at North American transplantation policies that affect living organ donation. European countries could adopt aspects of these policies with the aim of reducing the number of pediatric transplant professionals experiencing ethical dilemmas. Ethical issues can have a negative effect on donors, recipients, families, and the clinicians themselves.31 Therefore, supporting transplantation professionals that experience ethical dilemmas will ultimately lead to improved care for patients and satisfaction of healthcare staff.

In conclusion, this study found that ethical issues were commonly experienced by pediatric transplant professionals in all areas of transplantation. Important ethical concerns identified were the psychosocial evaluation of transplant candidates and follow-up care of living donors. The development of ethical guidelines was requested by the pediatric transplant community. This study concluded that a professional's role or region of work can affect the experience of ethical issues among professionals working in pediatric transplantation. A multidisciplinary approach was identified as a vital factor in successful tackling these ethical issues.

Further research, exploring in detail the common themes and ethical issues identified in this study could mark an important turning point toward an increased priority in pediatric transplantation ethics research. This increased prioritization will ultimately lead to changes in practice and create a fairer and more ethically acceptable transplant system.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ZA wrote and reviewed the manuscript, JH performed data collection, MIM, DB and DSL helped set up the study and wrote and reviewed the manuscript, SDM conceptualized, wrote, and review the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors of this study would like to thank all the members of the International Pediatric Transplant Association (IPTA) who in completing this survey have helped in better understanding the ethical dilemmas in pediatric transplantation. We would also like to acknowledge the help our colleagues involved in the extremely useful discussions in the focus group. This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been reported by the authors.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions