Directly observed therapy to promote medication adherence in adolescent heart transplant recipients

Funding information

This research was support by Florida State University Office of the Vice President of Research COVID-19 Pandemic Funding

Abstract

Purpose

HT recipients experience high levels of medication non-adherence during adolescence. This pilot study examined the acceptability and feasibility of an asynchronous DOT mHealth application among adolescent HT recipients. The app facilitates tracking of patients’ dose-by-dose adherence and enables transplant team members to engage patients. The DOT application allows patients to self-record videos while taking their medication and submit for review. Transplant staff review the videos and communicate with patients to engage and encourage medication adherence.

Methods

Ten adolescent HT recipients with poor adherence were enrolled into a single-group, 12-week pilot study examining the impact of DOT on adherence. Secondary outcomes included self-report measures from patients and parents concerning HRQOL and adherence barriers. Long-term health outcomes assessed included AR and hospitalization 6 months following DOT.

Findings

Among 14 adolescent HT patients approached, 10 initiated the DOT intervention. Of these, 8 completed the 12-week intervention. Patients and caregivers reported high perceptions of acceptability and accessibility. Patients submitted 90.1% of possible videos demonstrating medication doses taken. MLVI values for the 10 patients initiating DOT decreased from 6 months prior to the intervention (2.86 ± 1.83) to 6 months following their involvement (2.08 ± 0.87) representing a 21.7% decrease in non-adherence, though not statistically significant given the small sample size.

Conclusions

Result of this pilot study provides promising insights regarding the feasibility, acceptability, and potential impact of DOT for adolescent HT recipients. Further randomized studies are required to confirm these observations.

Abbreviations

-

- AMBS

-

- adolescent medication barriers scale

-

- AR

-

- acute rejection

-

- DOT

-

- video directly observed therapy

-

- EHR

-

- patient electronic medical record

-

- HRQOL

-

- health-related quality of life

-

- HT

-

- heart transplant

-

- ITT

-

- intent-to-treat analytic assumption

-

- LOCF

-

- last observation carried forward

-

- mHealth

-

- mobile health

-

- MLVI

-

- medication level variability index

-

- PedsQL

-

- PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales

-

- PedsQL-TM

-

- PedsQL 3.0 Transplant Module

-

- PMBS

-

- parent medication barriers scale

-

- PSSUQ

-

- Post Study System Usability Questionnaire

-

- SMS messaging

-

- Short Message Service messaging

1 INTRODUCTION

With technical and medical advances, overall life expectancy after heart transplantation has greatly improved in the last decades. Although short-term survival rates post-heart transplantation are high, long-term survival is greatly affected by patient non-adherence to the medical regimen, especially medication.1-5

Adolescence remains a challenging developmental period for any patient experiencing a chronic illness given the biological, psychological, and social developmental challenges.6, 7 During adolescence, parents and physicians expect their young patient to assume a greater level of involvement in their medical care by giving them increased responsibility for taking their medications, assessing their own symptoms of an illness, and monitoring their overall health. Difficulties assuming responsibility and challenges with self-monitoring their care, following their medical regimen, as well as dealing with social and peer pressures, and family factors, all of which contribute to lower medication adherence among adolescents during this time.1, 8-10 Pediatric transplant recipients have non-adherence rates as high as 40% to 60% during adolescence.1, 11-14 A meta-analysis of pediatric transplantation outcomes estimated adolescents were about twice as likely to be non-adherent as compared to younger patients.11 Non-adherence remains a significant predictor of poor post-transplant outcomes.1, 5 Adolescent patients have greater number of rejection episodes15-17 and earlier incidence of the first rejection episode when compared to younger children.18

Few appropriate interventions are available to target medication adherence in pediatric organ transplant recipients, let alone higher-risk adolescents.5, 19 More recently, mHealth technologies have gained traction in many chronic disease management settings, including cardiovascular disease and cystic fibrosis.20, 21

The need to develop and examine mHealth approaches for patient care, especially those addressing critical health behaviors, has increased dramatically due to the COVID-19 pandemic.22, 23 Increased access and use of personal technology and mobile smart devices among adolescents and their families24-28 with an estimated rate of 81.1% for adolescents (ages 12–17) and 95.7% for young adults (ages 18–24)29 has allowed the exponential increase in mHealth approaches. Moreover, broadband adoption and access have increased nationally, even among younger populations and those of lower socio-economic means.30, 31

Researchers and physicians have increasingly called for greater use of technology and mHealth approaches to engage adolescent transplant patients and foster greater medication adherence32-34 while adolescent patients and their families are becoming increasingly more accustomed to mHealth approaches.24, 26, 35, 36

Integrating mHealth components to promote patient health and nurture communication with healthcare professionals has the potential to transform all stages of transplant care from listing through post-transplant periods.37 However, the use of mHealth approaches to support behavioral change, such as promotion of medication adherence, remains a challenge.27 Many currently available mHealth interventions addressing medication adherence address only a single risk factor for non-adherence, namely forgetfulness, through reminders sent via text or in-application notifications.24, 38, 39 This functionality essentially combines an alarm clock and a text message, which elicits little patient engagement and change in behavior.28, 40

A 2018 statement from the American Society of Transplantation41 recommends that interventions should address multiple factors affecting adherence, which is a multifaceted and dynamic behavior. Ideally, interventions seeking to improve medication adherence need to improve patients’ organizational skills, planning, and conscientiousness around the behavior. Additionally, interventions should provide real-time feedback and monitoring, facilitate immediate and meaningful interpersonal support, and increase patients’ understanding of their chronic health condition and their medications.39, 41 mHealth interventions promoting adherence have the opportunity to address multiple risk factors for non-adherence while providing interpersonal interaction, support, and patient engagement.19, 39

emocha Mobile Health Inc. has developed a mHealth DOT application to engage patients and promote medication adherence. The app enables users to track dose-by-dose medication-taking behaviors asynchronously.42, 43 Specifically, patients can use the app to self-record videos of themselves as they take their medication and submit the videos for review. In the video, patients are asked to show the medication and demonstrate taking the medication. Notifications are sent to patients via SMS to remind them when they need to take their medications and what medications to take, as well as to prompt them to submit their videos for review. Nursing staff reviews the videos for correct medication, dosage, and time of administration.

Unlike typical mHealth medication adherence interventions, DOT seeks to address multiple risk factors of non-adherence.39, 41 The DOT application allows patients to see their progress, report any symptoms or side-effects, ask to speak to their transplant team, and interact or engage with the nurse monitoring submitted videos. Nursing staff monitoring video submissions and patient progress may in turn escalate concerns and patient reports to the transplant care provider. Most importantly, the DOT application offers patients greater interpersonal engagement, interaction, and encouragement than prior mHealth interventions conducted in pediatric organ transplant populations. Reviewing nurses may message patients to offer encouragement, build rapport, and offer support through various modes and frequencies of communication (email, phone call, or chat message). An additional benefit of DOT to the transplant care team and to researchers is the use of submitted videos as an objective and directly observed measure of adherence.

Previous research of telehealth or mHealth interventions focusing on adolescent adherence behaviors have focused on efforts to facilitate transition of care from pediatric to adult services,44 the use of telehealth cell phone support interventions,45 and mHealth applications to promote medication adherence and enhance communication about medication management.28 This pilot DOT intervention evaluation and collaboration builds on these trends in research and practice in pediatric heart transplantation and clinical practice around adherence. With these innovations in the DOT application and in-app functionality, we hypothesized that adolescent HT patients would demonstrate high daily dose adherence during the intervention and both adolescent and parental perceptions of barriers to medication adherence and perceived HRQOL would improve following completion of the intervention period. HRQOL in pediatrics encompasses physical health, socio-emotional health, and condition-specific aspects of having received an organ transplant.46-48 As such, the DOT application and intervention were hypothesized to improve communication between patients and their transplant team, reduce treatment anxiety, decrease concerns about their medications, and improve overall socio-emotional functioning. The mobile-based DOT contributes to changes in these aspects of HRQOL by allowing patients to receive encouragement and feedback around their medication-taking behaviors, thus enabling greater engagement and strengthening connections with their care and transplant teams.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

The proposed study was a prospective, single-group design intended to pilot a 12-week asynchronous DOT intervention in pediatric HT recipients (10–21 years). The study sought to enroll 10 adolescent transplant recipients and their parents. Participant enrollment continued until 10 participants initiated the DOT program. Once consented, subjects (patients and parents) completed a pre-intervention survey to assess baseline quality of life and adherence. A phone interview at 3 weeks was performed to assess feasibility and acceptability. At 12 weeks, subjects completed a post-intervention survey and an exit interview.

2.2 Procedure

Ten adolescent HT recipients were recruited from a large pediatric HT program in the southeastern United States. No research specific clinic visits were conducted to recruit and enroll patients due to safety concerns for an immunosuppressed patient population during the COVID-19 pandemic. All recruitment, consenting for participation, and patient enrollment were accomplished entirely remotely over the phone or during a scheduled evaluation. Once parents and patients were consented and assented, respectively, each were contacted by a researcher to complete pre-intervention surveys to assess baseline study characteristics and survey measures. As part of the onboarding process, personnel from emocha Health Inc. helped patients download and install the DOT application on their personal mobile devices, assisted with the initial setup, and provided a brief overview of the functionalities and how to use the app. After completing 3 weeks of the DOT intervention, a researcher contacted each participant and their caregiver to assess initial impressions about the program, participant satisfaction with the DOT application, and perceptions of its functionality. Upon completion of the 12-week intervention, patients and caregivers were again contacted, asked to complete the post-intervention survey, and were debriefed regarding the study. A flow chart detailing the enrollment, trainings, measurement points, and staff responsibilities during the DOT intervention has been previously published.49

2.3 Sample

Adolescents aged 11–21 who (a) had received a HT more than 6 months prior to enrollment, (b) a history of difficulties with medication adherence, and (c) were otherwise medically stable (as determined by the transplant team), were eligible to be recruited for possible participation. Poor medication adherence was determined by either problematic MLVI5 values ≥2.0 or by recommendation from the interdisciplinary transplant team. Evidence of poor adherence included patient and parental reports of non-adherence, self-reports of forgetfulness, patient reports of not wanting to take medication, and parents discussing the patient having difficulty with medication taking and exhibiting erratic medication-taking behavior. Non-English-speaking participants were not recruited in this pilot due to the interactive nature of the intervention, and the availability of only English-speaking monitoring staff. Due to the interactive nature of this pilot study and their inability to provide informed assent, we also excluded patients with developmental delay cognitive impairments. Patients were compensated a maximum of $114 for participation in the study ($1 per day of video submission and $10 per completed interviews).

2.4 Intervention and pilot phase

For each participant, a transplant provider or coordinator on the study team entered prescribed medications and times when they were scheduled to take the medications. As a second check, another member of the study team ensured that medications entered into the DOT application were consistent with what was found within the EHR to reduce the risk of transcription error. In addition, patients reviewed their own medication list in the application to ensure accuracy.

An escalation protocol was developed and implemented by emocha staff and research personnel. Each reason for escalation in the protocol had an associated method of detection by nursing staff reviewing the video submissions, a response to the patient, timeline for study staff response, and example chat messages to be sent to study patients. Reasons for escalation included missed doses or video submissions, reports of side-effects from medication, administration problems (e.g., too much or little medication, incorrect timing of administration), urgent patient health and safety concerns (e.g., patient hospitalized, dangerous living condition observed in video, reports of suicidal thoughts), and non-adherence behaviors (e.g., forgetfulness, reports of not wanting to take medication, lack of pill organization). Responses to the patient, transplant care team, and study staff were customized for each escalation type and severity. Patient medication entry into the DOT platform, review of submitted videos, messaging with patients, and management of the escalation protocol was conducted by a study nurse, provided by emocha.

2.5 mHealth and DOT acceptability metrics

In order to ensure acceptability among the patients who engaged in DOT, the participants’ overall satisfaction in using the app was assessed during the third week of use. In addition, we examined consent rate and use of the DOT app by participants over time to understand acceptability of using the application.

2.6 Measurement of adherence and long-term health outcomes

2.6.1 Dose-by-dose directly observed adherence

DOT and the mobile application tracked medication taking through direct observation. Number of possible doses were compared to the number of videos patients submitted that demonstrated medication taking.

2.6.2 AR and hospitalization outcomes

Data were collected on adverse medical outcomes for all patients. Each instance of AR and hospitalization was collected as distal health outcomes and compared for each patient before and after involvement in the DOT intervention.

2.6.3 MLVI

Routine post-transplant medical care for these children involve frequent blood tests during visits, which assess the levels of immunosuppressant medication. Medication adherence research in organ transplantation is increasingly using blood tests and medication values.5, 14 MLVI is obtained by calculating the standard deviation of tacrolimus levels per patient, which are obtained during regular clinical care and outpatient appointments, generally once per 3 months. Higher MLVI scores for the immunosuppressant medication, tacrolimus (Prograf or FK506), would indicate lower consistency in taking the medication and, therefore, less medication adherence.50-57 Importantly, MLVI scores were found to predict LAR within a large, multi-site study of pediatric liver transplant recipients.5 MLVI was calculated for each patient using at least three tacrolimus trough blood levels.5, 58-60 MLVI values were calculated 6 months prior to enrollment as part of the screening process and again calculated during DOT and 6-months follow-up periods.

2.7 DOT user experience and acceptability

Perceived usability of the app was measured using PSSUQ, a validated measure used in the development of technological applications61, 62 and via open-ended questions about patient and caregiver impressions of DOT and specifically the mHealth app. The PSSU is a 16-item user experience survey rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree—to 7-strongly agree). The PSSUQ was used in a previous feasibility trial of another telemedicine approach to address medication adherence with adolescent transplant recipients.28 Patients and caregivers were also asked about their overall satisfaction with the app using and open-ended questions administered during the 3- and 12-week interviews.

2.8 Measurement of adolescent and parent reported outcomes

2.8.1 Generic HRQOL

PedsQL63 is a 23-item measure of HRQOL composed of subscales assessing Physical Functioning, Emotional Functioning, Social Functioning, and School Functioning. The PedsQL has numerous versions available based on the age of the child and includes both child self-report and parental proxy-report. This measure has demonstrated reliability in both the adolescent self-report (subscales ranging from α = 0.79 to 0.89, total scale α = 0.91) and parent proxy-report (subscales ranging from α = 0.77 to 0.89, total scale α = 0.92). Additionally, parent-adolescent inter-rater agreement (r = 0.68), construct validity, and known-groups validity in a large pediatric sample of health and chronically ill children.63-67

2.8.2 Disease-specific HRQOL

The PedsQL-TM68 offers assessment of HRQOL particularly relevant to pediatric organ transplant recipients. This PedsQL-TM captures aspects of HRQOL in adolescent transplant recipients such as perceptions around barriers to medication adherence, concerns about medication side-effects, social relationships and transplant, treatment anxiety, general anxiety about their health status, and their perceived challenges in communicating with transplant team members. The PedsQL-TM has demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency reliability with both the adolescent self-report (subscales ranging from α = 0.76 to 0.85, total scale α = 0.91) and parent proxy-report (subscales ranging from α = 0.81 to 0.91, total scale α = 0.94). Across transplant types, the PedsQL-TM has shown psychometric validity and reliability.46

2.8.3 Barriers to adherence

The AMBS and the PMBS was used to assess adolescent perceived barriers to medication adherence and parent perceived barriers to their child taking their medication, respectively.69, 70 Both versions consist of three subscales including Disease Frustration/Adolescent Issues, Ingestion Issues, and Regimen Adaptation/Cognitive. Each version of the overall measure has demonstrated reliability, construct validity, and predictive validity in prior research involving adolescent transplant recipients and their parents.71

2.9 DOT user engagement – app usage

User engagement and app usage was determined by extracting all messages exchanged between the patients and the reviewing nurse or other staff in the DOT application. The total number of messages exchanged and the total number sent by the patient were used in analyses.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Differences between those patients consenting and not initiating DOT were compared to those at least beginning the intervention to assess baseline differences in the sample. When comparing scores and MLVI values to those for patients following their involvement in DOT, an ITT using LOCF was taken to account for those patients dropping out of the intervention before completing 12 weeks. Depending on the level of measure for variables, statistical tests included Spearman's rho (ρ) non-parametric correlation and each Wilcoxon paired samples rank sign and McNemar change tests for dependent samples (tests of changes in scores over time). Independent samples Mann-Whitney U tests, chi-square tests (χ2), and Fisher's exact tests were used to examine association between groups and outcome variables. Effect size metrics included Hedge's g for independent sample tests, r for Wilcoxon paired samples signed rank tests, phi (ϕ) for χ2 and Fisher's exact tests, and Cohen's g for McNemar change tests.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample demographics and attrition

A total of 14 patients were identified and recruited for participation in the pilot DOT program (Table 1). Four patients (28.6%) initially consented but did not attend onboarding sessions and later declined participation. Two patients completed 3 weeks of the intervention before discontinuing video submissions and communication with nursing staff. According to study and escalation protocols, these patients were considered to have dropped out of the DOT intervention after seven consecutive days of not submitting videos.

| Patient characteristics | Total, n = 14 | Completed, n = 8 | Dropped out, n = 6 | Test statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age, years, M ± SD | 17.24 ± 2.83 | 15.75 ± 2.66 | 19.17 ± 1.72 | U = 6.50*, g = 1.38 |

| Range (min.–max.) | 12–21 | 12–21 | 16–21 | |

| Time since transplant, years, M ± SD | 6.50 ± 5.40 | 5.89 ± 6.21 | 7.31 ± 4.52 | U = 19.00, g = 0.24 |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 8 (57.1%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | Exact p = 1.00, ϕ = 0.13 |

| Race, minority, n (%) | 6 (42.9%) | 2 (25.0%) | 4 (66.7%) | Exact p = .28, ϕ = 0.42 |

| Parent age, years, M ± SD | 38.89 ± 3.26 | 37.50 ± 3.54 | 39.29 ± 3.35 | U = 9.50, g = 0.47 |

| Type of insurance at transplant, n (%) | Exact p = 1.00, ϕ = 0.00 | |||

| Medicaid | 7 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Private | 7 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Patient hospitalized at transplant, n (%) | 11 (78.6%) | 7 (87.5%) | 4 (66.7%) | Exact p = .54, ϕ = 0.25 |

| Patient in ICU at transplant, n (%) | 6 (42.9%) | 3 (37.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | Exact p = 1.00, ϕ = 0.13 |

| Coronary allograft vasculopathy (CAV), n (%) | ||||

| None | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Mild | 8 (57.1%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Moderate to severe | 4 (28.6%) | 1 (12.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| MLVI values at DOT enrollment, M ± SD | 2.99 ± 1.73 | 2.42 ± 1.58 | 3.75 ± 1.75 | U = 11.00, g = 0.75 |

| Median | 2.49 | 1.94 | 3.17 | |

| Range (min.–max.) | 1.78–6.17 | 0.95–5.32 | 1.78–6.17 | |

| MLVI >2.0, n (%) | 9 (64.3%) | 4 (50.0%) | 5 (83.3%) | |

- * p < .05.

Overall, the eight patients completing the 12-week DOT program ranged in age from 12 to 21 years and had a mean time since transplant of 5.89 ± 6.21 years. Majority were female (n = 5, 62.5%), had mean MLVI scores of 2.54 ± 0.65, and had a pre-transplant diagnosis of congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or a graft rejection requiring a retransplantation. Those patients completing the 12-week intervention program tended to be younger, white, and have lower MLVI values 6 months prior to participation (i.e., greater pre-intervention adherence). Insurance type (public vs. private) as a proxy-measure for socio-economic status was not predictive of attrition.

3.2 Acceptability interviews

Data related to perceived feasibility and acceptability was assessed using the PSSUQ 3 weeks into the DOT intervention and through open-ended questions at both 3- and 12-week interviews. Responses from each time point demonstrated high overall participant satisfaction with the program and the DOT app. Responses on the PSSUQ items yielded consistent responses (mean ranged from 1.00 to 2.00 on scale of 1–7), while only a few had any response variability (ranges 1–4). A majority of the participants rated the DOT application as very high quality across all items. Only two items had slightly lower ratings including “The system gave error messages that clearly told me how to fix problems” (M = 2.00 ± 1.20) and “Whenever I made a mistake using the system, I could recover easily and quickly” (M = 1.88 ± 1.13).

During 3- and 12-week interviews, both patients and parents reported that they appreciated the organizational value (e.g., videos submissions, a log of taken doses, reminders to take medication) of the DOT application as well as the ability to communicate and engage with nursing staff monitoring the video submissions (e.g., messages and texting). Parents reported increases in their adolescent's knowledge of medication and in their adolescent's engagement within decision-making around medication and general post-transplant care. Older adolescents and young adults noted that the DOT application allowed them to integrate medication taking more easily into their daily schedules. These patients reported that the application served as a valuable aid for medication tracking which further supported autonomy and freedom during their daily activities. Direct quotations from patients and parents are provided (Supplementary Materials).

3.3 Escalations

A total of 39 escalations were reported for 8 patients in the study per the escalation protocol. Of these 39, 20 escalations were due to two patients dropping out of the study following seven consecutive days of missing doses as evidenced by submitted videos. The 19 escalations for those patients completing all 12 weeks of the DOT intervention included missed doses or video submissions (n = 7, 36.8%), a reviewer concern with the timing of the dose (n = 4, 21.1%), patient reports of experiencing medication side-effects (n = 3, 15.8%), and provider reports of changes to medication regimen (n = 2, 10.5%). Escalations most often only resulted in calls and messages to the provider (n = 15, 78.9%) or a text message to the patient (n = 3, 15.8%).

3.4 Text messages and patient to nurse messaging

A total of 893 in-app messages were exchanged between the 10 patients participating in the intervention and the reviewing nursing staff. Of these, 205 messages (23.0%) were from the patient to the nursing staff. Per patient completing the 12-week intervention, the mean number of messages were 92.75 ± 13.23 in total and 22.25 ± 9.84 sent by the patients. Overall, number of escalations were associated with the total number of messages exchanged (ρ = 0.444, p = .270) and the number of those uniquely sent by the patient (ρ = −0.194, p = .645). The correlation between total number of messages exchanged and number of escalations had a moderate effect size yet was not statistically significant due to low sample size (n = 8). Results indicate that as escalations increased, total number of messages followed suit although with less patient interaction through in-app messaging.

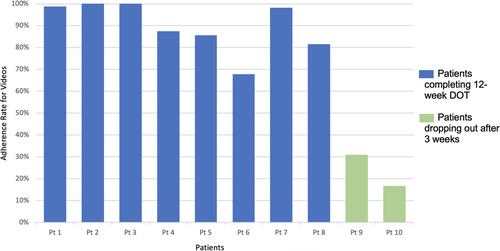

3.5 Adherence per day and overall rates

Adherence data extracted from the emocha app and platform indicated that the eight patients completing the 12-week DOT submitted 1211 videos of a possible 1344, assuming 84 days with two videos per day for morning and evening doses. This translated to 90.1% adherence to medication observed directly from videos as reviewed by nursing staff (Figure 1). The two participants who dropped out did so by the third week and had submitted 31.0% and 16.0% of videos before being considered inactive and having dropped out, per the intervention and escalation protocol. Assuming these two patients maintained these rates of adherence for a full 12-week intervention, using an ITT analytic assumption, the resulting rate of adherence to medication observed by nursing staff on video would have been 76.8% for all 10 patients. Overall, for the time that each participant was in the intervention (n = 10), 1291 videos were submitted of a possible 1558 (82.9% adherence rate). Total number of messages (ρ = −0.219, p = .543) and number of messages sent from patient to reviewer (ρ = 0.198, p = .583) were not significantly correlated with proportion of videos submitted while in the program.

3.6 Patient self-report and parent proxy-report measure results

Patients and caregivers reported significant improvements in many areas within their perceptions of medication barriers (AMBS and PMBS scores) and on key transplant-specific HRQOL measures from baseline to post-DOT interviews. Results presented in Table 2 take attrition into consideration using an ITT and LOCF analytic approach to produced unbiased results.

| Measure score | Pre-DOT | Post-DOT, 12-week | Test (Z) | Effect size (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBS total | 37.10 ± 12.15 | 29.60 ± 10.12 | 2.29* | .723 |

| Disease frustration/adolescent issues | 18.80 ± 7.10 | 15.70 ± 6.88 | 1.75 | .555 |

| Regimen adaptation/cognitive | 10.20 ± 4.08 | 7.60 ± 3.78 | 2.32* | .735 |

| Ingestion issues | 8.100 ± 3.45 | 6.30 ± 2.26 | 2.29* | .726 |

| PMBS total | 37.14 ± 9.37 | 23.57 ± 6.13 | 2.29* | .864 |

| Disease frustration/adolescent issues | 13.71 ± 4.39 | 10.29 ± 2.87 | 2.03* | .768 |

| Regimen adaptation/cognitive | 15.14 ± 5.27 | 7.86 ± 3.89 | 2.29* | .866 |

| Ingestion issues | 4.43 ± 1.62 | 3.43 ± 1.13 | 1.34 | .505 |

| PMBS parental reminder | 3.86 ± 1.46 | 2.29 ± 1.60 | 1.90 | .720 |

| PedsQL generic—patient | ||||

| Physical functioning | 71.56 ± 19.51 | 76.25 ± 23.12 | 1.02 | .322 |

| Emotional functioning | 55.50 ± 20.34 | 68.00 ± 27.51 | 1.97* | .621 |

| Social functioning | 85.00 ± 12.25 | 90.00 ± 9.43 | 1.50 | .473 |

| School functioning | 59.50 ± 17.39 | 73.50 ± 18.57 | 2.47* | .780 |

| PedsQL generic—parent | ||||

| Physical functioning | 70.54 ± 17.94 | 79.91 ± 17.39 | 2.30* | .869 |

| Emotional functioning | 66.43 ± 25.61 | 75.00 ± 18.71 | 0.83 | .313 |

| Social functioning | 71.43 ± 26.25 | 82.86 ± 19.55 | 0.95 | .358 |

| School functioning | 38.57 ± 19.94 | 70.71 ± 21.88 | 2.29* | .866 |

| PedsQL transplant module—patient | ||||

| About my medicines I | 83.61 ± 10.35 | 91.67 ± 8.78 | 2.03* | .643 |

| About my medicines II | 93.44 ± 6.82 | 97.50 ± 4.61 | 1.49 | .471 |

| My transplant and others | 71.25 ± 12.74 | 77.50 ± 14.86 | 1.78 | .563 |

| Pain and hurt | 70.00 ± 22.29 | 75.83 ± 24.36 | 1.08 | .343 |

| Worry | 63.21 ± 22.34 | 72.50 ± 27.72 | 2.11* | .667 |

| Treatment anxiety | 63.75 ± 27.92 | 74.38 ± 23.65 | 1.26 | .399 |

| How I look | 81.67 ± 28.81 | 89.17 ± 21.17 | 1.34 | .423 |

| Communication | 68.13 ± 22.72 | 82.50 ± 21.61 | 2.30* | .727 |

| PedsQL transplant module—parent | ||||

| About my medicines I | 77.78 ± 12.63 | 94.84 ± 6.50 | 2.10* | .792 |

| About my medicines II | 88.84 ± 8.04 | 99.11 ± 2.36 | 2.11* | .797 |

| My transplant and others | 58.48 ± 13.47 | 82.14 ± 9.15 | 2.10* | .795 |

| Pain and hurt | 63.10 ± 28.41 | 95.24 ± 9.45 | 2.10* | .795 |

| Worry | 70.41 ± 17.82 | 91.84 ± 8.92 | 2.42* | .914 |

| Treatment anxiety | 46.43 ± 36.24 | 83.93 ± 17.25 | 2.10* | .795 |

| How I look | 84.52 ± 23.78 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 1.66 | .626 |

| Communication | 62.50 ± 24.21 | 87.50 ± 20.09 | 2.29* | .866 |

- * p < .05.

Adolescent and parental reported barriers to medication adherence decreased over the course of the 12-week DOT program. AMBS (Z = 2.29, p = .022, r = .723) and PMBS (Z = 2.29, p = .022, r = .864) total scores each decreased from pre- to post-intervention testing as well as both of the AMBS and PMBS Regimen Adaptation and Cognitive Issues subscale scores (AMBS Z = 2.32, p = .020, r = .735; PMBS Z = 2.29, p = .022, r = .866). Patient and parents reported significant improvements in perceptions of their medication, planning, organization, and overall communication with their pediatric transplant care team. Numerous subscales of the PedsQL-TM were reported as improving, including patient-reported medication issues, treatment worry, and communication with the transplant team. Parent-reported PedsQL-TM scores in nearly all facets over the 12-week intervention. General HRQOL was reported to be significantly higher following the DOT intervention regarding patient-reported emotional functioning, parent-reported physical functioning, and both patient- and parent-reported school functioning.

3.7 MLVI

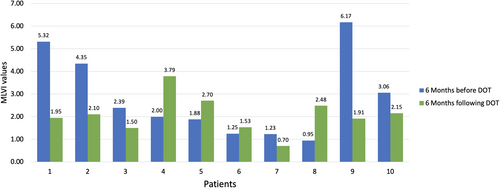

MLVI (Table 3; Figure 2) for the 10 patients who initiated DOT decreased from the 6 months prior to participating in the intervention (2.86 ± 1.83) to the 6 months following their involvement (2.08 ± 0.87). The mean change in MLVI was 0.62 ± 2.07 representing a 21.7% reduction among these 10 patients with a moderate effect (Hedge's g = 0.369), though this was not statistically significant (Z = 1.07, p = .285). The proportion of the intervention sample with a MLVI value greater than 2.0 decreased from 6 (60.0%) to 4 (40.0%), again while this was not statistically significant (McNemar change p = 1.00) it reflected a moderate effect (Cohen's g = 0.60). All four patients with very high MLVI prior to the DOT intervention (MLVI > 3.0) demonstrated improved adherence during the 6 months following the intervention (MLVI < 3.0). The number of messages exchanged between the patient and reviewer (ρ = −0.369, p = .294) and the number sent by the patient (ρ = −0.298, p = .403) were each negatively correlated with MLVI following DOT involvement although this was not statistically significant.

| Patient characteristics | 6 months prior to DOT | 6 months following DOT | Change | Test statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLVI values, M ± SD | 2.86 ± 1.83 | 2.08 ± 0.87 | 0.62 ± 2.07 | Z = 1.07, p = .285 |

| Median | 2.19 | 1.95 | 0.53 | |

| Range (min.–max.) | 0.95–6.17 | 0.70–3.79 | −1.78 to 4.25 | |

| Non-adherence, MLVI >2.0, n (%) | 6 (60.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | McNemar change p = 1.00, Cohen g = .60 |

3.8 Long-term outcomes

One patient completing DOT (n = 8) had hospitalizations unrelated to AR in the 6 months following involvement in the intervention, while 83.3% of those patients not beginning DOT or dropping out (n = 6) were hospitalized or experienced episodes of AR. These results were statistically significant with a large effect (Fisher's exact p = .026, ϕ = .708). Unfortunately, two patients who either did not begin DOT or dropped out after less than 3 weeks died secondary to complications associated with coronary allograft vasculopathy. Those patients hospitalized in the 6 months following DOT involvement had significantly higher MLVI (4.02 ± 1.83, Z = 2.03, p = .043) compared to those not hospitalized (2.08 ± 0.82)—a large effect (Hedge's g = 1.80).

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

With paucity of donor organs and increasing waitlist mortality, every effort is required to optimize allograft survival and patient outcomes, especially among adolescent patients with demonstrated higher prevalence of non-adherence. In this context, piloting a DOT intervention is a potential advancement in research and clinical care of adolescent HT recipients. We sought to recruit difficult to reach patients exhibiting poor medication adherence. Often, adherence intervention researchers recruit and enroll patients only at clinical visits, which can lead to exclusion of higher-risk patients likely with poor rates of clinic visit attendance.19, 72

Across the 12-week intervention, rates of medication adherence, as evidenced by virtually but directly observed medication-taking behavior, were high with 90.1% of adherence with video submissions observed and reviewed by nursing staff. Of course, these rates were lower when considering attrition and ITT assumptions. MLVI scores largely improved from 6 months before to 6 months after DOT involvement, representing on average a 21.7% decrease in MLVI values with a moderate effect size. Patient self-reported and parent proxy-reported survey measure scores improved significantly from baseline to post-intervention, especially in the areas of medication barriers around regimen adaptation, cognitive issues, and HRQOL issues around medication, worry, and communication with care providers.

Assessment of the impact of DOT on long-term health outcomes demonstrated that those patients completing the intervention had no adverse medical outcomes in the 6 months following involvement in DOT. The two patients who died during this time were those who did not start or completed the DOT program. Very importantly, those patients who consented but did not begin the DOT and those who dropped out from the intervention after 3 weeks were patients who were on average older, with greater non-adherence, and with greater medical morbidities.

Overall, adolescents and their parents reported positive perceptions of the DOT similar to other studies of mHealth and telehealth approaches with similar samples of patients.73 Patients and family members reported high overall participant satisfaction with the program and the DOT app, especially with regards to patient engagement, interaction, and encouragement. High levels of reported acceptability and satisfaction are important for DOT where real-time monitoring and direct observation may be perceived as a treatment burden by adolescent patients. Parents reported observing improvements in their patient's organization skills, planning, and understanding of their chronic health condition and medications.

4.1 Limitations

This pilot study on the acceptability, feasibility, and initial efficacy of DOT with adolescent HT recipients has a number of limitations, which must be considered, the most critical of which include the limited sample size, lack of a control group, and limited follow-up measurement. Although 14 patients and their caregivers were approached for possible participation, eight completed the 12-week DOT intervention. The purpose of the study was to address medication-taking behaviors in a sample of non-adherent patients, which may have led to increased attrition throughout the process. These are patients already demonstrating challenges with the treatment regimen, so attrition at this rate and attrition among the most non-adherent patients was expected. A meta-analysis of mHealth approaches with patients experiencing chronic illness reported an aggregated attrition rate of 43% across studies.45, 74 Other mHealth intervention pilot studies targeting non-adherence in pediatric transplantation have reported similar high levels of attrition.75 Patients with non-adherence are less likely to be recruited into research,72, 76 and recruiting only adherent patients with more consistent clinical attendance leaves many studies unable to examine the impact of the interventions aiming to promote medication adherence.60 Our study sought out the least adherent patients who also may be the most difficult to engage in any behavioral intervention. Regarding time spent engaging patients during the intervention, and the time taken responding to messages was not examined explicitly due to the small sample size. However, in our larger study, we will look at the time involvement required of nursing staff to better gage scalability for transplant centers and translation of this approach to a larger number of patients. This DOT intervention with increased interpersonal engagement may offer a better vehicle for encouraging patients to change their behavior and habits related to medication taking.

Limitations in the outcome measurement in this pilot study should also be considered. Concerning the effect sizes and increases in self-report and proxy-reported survey measures, acquiescent response and social desirability biases may have contributed to increases in post-intervention survey outcomes. Future research should and will include control groups within a more robust trial to control for these possible effects.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Research on promotion of health behaviors and self-management skills in adolescents experiencing a chronic illness has a number of implications for sustainability and clinical implications for the care of these adolescents and their families. This study is significant as there has been increased focus on and calls for advancement and integration of technology particularly within high-risk pediatric interventions.53, 77, 78 The current DOT application offered higher quality of patient engagement through interaction with program nursing staff and opportunities to escalate concerns with their own pediatric transplant care team. The current study represents an advancement in mHealth research, actively recruited difficult to reach patients with adherence challenges, and directly assessed adherence through direct observation. This is a proof of concept of a well-developed and implemented mHealth intervention that can enhance patient engagement, interaction, and encouragement, potentially leading to a positive impact on medication non-adherence especially among high-risk adolescent populations. Future mixed-methods research and clinical trials should examine specific factors of DOT, which may influence patient perceptions of engagement with the mHealth app and facilitate improvements with their medication-taking behaviors.

Overall, the results provide important promising insights regarding the feasibility, acceptability, and potential impact of DOT adherence intervention in clinical care of adolescent HT recipients. Further randomized trials are required to confirm the initial findings of our pilot study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MK and DG were responsible for the conception and design of the study, data collection, and manuscript preparation. MK conducted statistical analysis and patient interviews. GS and MLL assisted with data analysis and interpretation. SC conducted study procedures, assisted with data collection, and manuscript preparation.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the University of Florida Health Sciences Institutional Review Board with additional approval from the Florida State University Human Subjects Committee.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.