Morpho-anatomical and physiological differences between sun and shade leaves in Abies alba Mill. (Pinaceae, Coniferales): a combined approach

Abstract

Morphology, anatomy and physiology of sun and shade leaves of Abies alba were investigated and major differences were identified, such as sun leaves being larger, containing a hypodermis and palisade parenchyma as well as possessing more stomata, while shade leaves exhibit a distinct leaf dimorphism. The large size of sun leaves and their arrangement crowded on the upper side of a plagiotropic shoot leads to self-shading which is explainable as protection from high solar radiation and to reduce the transpiration via the lamina. Sun leaves furthermore contain a higher xanthophyll cycle pigment amount and Non-Photochemical Quenching (NPQ) capacity, a lower amount of chlorophyll b and a total lower chlorophyll amount per leaf, as well as an increased electron transport rate and an increased photosynthesis light saturation intensity. However, sun leaves switch on their NPQ capacity at rather low light intensities, as exemplified by several parameters newly measured for conifers. Our holistic approach extends previous findings about sun and shade leaves in conifers and demonstrates that both leaf types of A. alba show structural and physiological remarkable similarities to their respective counterparts in angiosperms, but also possess unique characteristics allowing them to cope efficiently with their environmental constraints.

1 INTRODUCTION

In addition to the availability of water and the soil fertility the morpho-anatomical structure and the physiology of leaves is strongly influenced by their exposure to light (Bresinsky, Körner, Kadereit, Neuhaus, & Sonnewald, 2008; Givnish, 1988; Weiler & Nover, 2008). Due to the complex branching pattern within a tree's crown, light exposed and shaded parts exist, sometimes even on the same branch. In light exposed, outer parts of the crown, sun leaves are developed mostly distal on plagiotropic and orthotropic shoots while shade leaves are developed typically on plagiotropic shoots in shaded, inner parts of the crown. On seedlings and juvenile trees growing in the dark understorey before reaching the light exposed parts of the canopy later, shade leaves can be found all over the crown (Beck, 2010; Bresinsky et al., 2008; Givnish, 1988; Weiler & Nover, 2008).

Sun leaves are light exposed during their entire ontogeny. When leaves/leaf primordia are shaded, in particular in early ontogenetic stages, shade leaf structure and physiology is developed. In previous studies it could be shown that the formation of sun and shade leaves is already triggered by the light exposure of the hibernating buds (Eschrich, Burchardt, & Essiama, 1989). When a mature leaf once is differentiated into either a sun leaf or a shade leaf, further structural changes are impossible even if light exposure changes later (Eschrich, 1995).

Different light exposure conditions lead to distinct morpho-anatomical and physiological differences of leaves. Sun leaves are smaller than shade leaves, show a higher leaf mass per area, are thicker and have higher palisade/spongy parenchyma ratio (Kim, Yano, Kozuka, & Tsukaya, 2005; Lichtenthaler, Ac, Marek, Kalina, & Urban, 2007; Rhizopoulou, Meletiou-Christou, & Diamantoglou, 1991). Furthermore, sun leaves have a higher stomata density (Boardman, 1977; Herrick & Thomas, 1999; Lichtenthaler et al., 2007; Marques, Garcia, & Fernandes, 1999; Mendes, Gazarini, & Rodrigues, 2001; Rijkers, Pons, & Bongers, 2000; Terashima, Hanba, Tazoe, Vyas, & Yano, 2006; Terashima, Miyazawa, & Hanba, 2001). However, their stomata are distinctly smaller than in shade leaves (Ashton & Berlyn, 1992; Beck, 2010; Bresinsky et al., 2008; Givnish, 1988; Weiler & Nover, 2008). In addition to these morpho-anatomical features, sun and shade leaves also differ distinctly in several physiological traits. In sun leaves the light saturation rate of photosynthesis is significantly higher than in shade leaves, as is also the case for the light compensation point, the light saturation irradiance and the chlorophyll a/b ratio (Alberte, McClure, & Thornber, 1976; Ashton & Berlyn, 1992; Gausman, 1984; Givnish, 1988; Herrick & Thomas, 1999; Leverenz, 1987; Lichtenthaler, 2007; Lichtenthaler et al., 1981; Lichtenthaler & Babani, 2004; Mendes et al., 2001). Shade leaves, in contrast, exhibit a higher amount of chlorophyll per leaf dry mass and area and concomitantly a higher allocation of nitrogen to light harvesting complexes (Hikosaka & Terashima, 1995; Niinemets, 2010; Valladares & Niinemets, 2008). Moreover, the capacity for photoprotection based on Non-Photochemical Quenching (NPQ), which relies on the violaxanthin cycle and the plastidic protein PsbS (Goss & Lepetit, 2015; Niyogi & Truong, 2013), is strongly increased in sun leaves (Demmig-Adams, 1998). In addition to structural morpho-anatomical and physiological traits sun and shade leaves also differ in the size, shape and number of chloroplasts. For example, in sun leaves the chloroplasts are smaller in size and the thylakoid/grana ratio is lower than in shade leaves (Beck, 2010; Bresinsky et al., 2008; Givnish, 1988; Lichtenthaler, 2007; Lichtenthaler et al., 1981; Lichtenthaler & Babani, 2004; Weiler & Nover, 2008).

Previous studies showed that the morpho-anatomical and physiological adaptations/responses of sun leaves are comparable to the foliar features of drought tolerant plants, while the situation in shade leaves resembles drought intolerant plants (Ashton & Berlyn, 1992).

The morphology, anatomy and physiology of sun and shade leaves have been subjected to several previous studies. However, the overwhelming majority of these studies focused on angiosperms (Gratani et al. 2000; Onwueme & Johnston, 2000), while gymnosperms were mostly neglected. Thus, within gymnosperms only a few studies dealing with this topic already exist (e.g. Czeczuga, 1987; Lichtenthaler et al., 2007; Sarijeva, Knapp, & Lichtenthaler, 2007; Urban, Kosvancova, Marek, & Lichtenthaler, 2007; Wyka et al., 2012) and hardly any combined study, dealing with morphological-anatomical and physiological aspects, can be found.

Thus, in the present comprehensive study the coniferous species Abies alba (Pinaceae) was used as an example to give insight into the morpho-anatomical structure and also the physiology of sun and shade leaves in a novel combined approach, by correlating and combining morpho-anatomical and physiological traits to each other.

2 MATERIAL & METHODS

2.1 Material

Material was collected in autumn 2016 and summer 2017 from trees growing in a temperate mixed forest on the campus of the University of Konstanz, Germany (47° 38‘N - 9° 8′E; altitude about 460 m; annual mean temperature 9.4° C; 946 mm annual precipitation). Sun leaves experienced light intensities of up to 1800 μmol photons m−2 s−1 in summer on a cloudless day, while shade leaves obtained between 10 and 20 μmol m−2 s−1, interrupted by rare light spots of up to 250 μmol m−2 s−1. Light intensity was measured with a spherical quantum sensor (US-SQS/L, Walz, Germany).

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Microtome technique

Freshly collected material was photographed and then fixed in FAA (100 ml FAA = 90 ml 70% ethanol +5 ml acetic acid 96% + 5 ml formaldehyde solution 37%) before being stored in 70% ethanol. The leaf-anatomy was studied from serial sections using the classical paraffin technique and subsequent astrablue/safranin staining (Gerlach, 1984).

2.2.2 Photodocumentation

Macrophotography was accomplished using a digital camera (Canon PowerShot IS2) and microphotography with a digital microscope (Keyence VHX 500F) equipped with a high-precision VH mounting stand with X-Y stage and bright-field illumination (Keyence VH-S5).

2.2.3 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

For SEM analysis, FAA-fixed material was dehydrated in formaldehyde dimethyl acetal (FDA) for at least 24 hours (Gerstberger & Leins, 1978) and critical-point dried, then mounted onto SEM stubs and sputter-coated using a sputter coater SCD 50 Bal-tec (Balzers). Specimens were examined using an Auriga Zeiss TM.

2.2.4 Mean number of abaxial stomatal rows and stomata

Investigated individuals: 5; material: 5 sun and 5 shade leaves per individual; calculation: for each leaf the total number of abaxial stomatal rows and number of stomata per mm2 was counted; arithmetic mean for abaxial stomatal rows per leaf = total number of counted stomatal rows: number of investigated leaves; arithmetic mean for stomata per mm2 per leaf = total number of counted stomata per mm2: number of investigated leaves.

2.2.5 Mean internode length

Investigated individuals: 5; material: 5 sun exposed and 5 shaded present year's growth units per individual; calculation: for each growth unit the length was measured and the number of inserted leaves was counted; arithmetic mean value for the internode length = total length of all measured shoots: total number of counted leaves.

2.2.6 Mean leaf area, length and diameter

Investigated individuals: 2; material: 100 sun leaves and 100 shade leaves per individual; calculation: leaves scanned with a standard scanner; total leaf area calculated by using the ImageJ software package; arithmetic mean value for the area of a single leaf = total measured leaf area: number of investigated leaves; the lengths and diameters of the scanned leaves were calculated in the same way.

2.2.7 Mean leaf thickness

Investigated individuals: 5; material: 5 sun and 5 shade leaves per individual; calculation: from each leaf a microtome cross sections was prepared; the leaf thickness was measured with the software corresponding to the digital microscope Keyence VHX 500F; arithmetic mean value for the thickness of a single leaf = the total measured values for the leaf thickness: the number of investigated leaves.

2.2.8 Mean leaf weight

Investigated individuals: 5; material: 5 sun and 5 shade leaves per individual; calculation: freshly collected material weighted; arithmetic mean value for the leaf water content = total leaf weight: total number of investigated leaves.

2.2.9 Mean dry weight

Investigated individuals: 5; material: 5 sun and 5 shade leaves per individual; calculation: freshly collected material weighted, then dried until reaching a constant in weight, then weighted again; arithmetic mean value for the leaf water content = (fresh weight – dry weight): total number of investigated leaves.

2.2.10 Pigment composition

For determination of the total chlorophyll amount, during summer 2017 100 needles of sun and shade leaves each from three different shoots were collected and pooled, then weighted. They were frozen in liquid nitrogen and pestled in 80% Acetone and some sea sand. After centrifugation (5000 g, 8 min, 4°C), the volume of the clear green supernatant was measured and chlorophyll amount was determined spectroscopically using the method of Ziegler and Egle (1965). The same supernatant was analysed with a calibrated Hitachi LaChrom Elite HPLC system (Japan) equipped with a 10°C cooled autosampler and a Nucleosil 300–5 C18 column (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). Eluents and gradient programs were as described in Kraay, Zapata, and Veldhuis (1992) and pigments were quantified according to Wilhelm, Volkmar, Lohman, Becker, and Meyer (1995). In order to determine the deepoxidation state (DES; DES = (czeaxanthin + 0.5cantheraxanthin) / (czeaxanthin + cantheraxanthin + cviolaxanthin), three additional pools of sun and shade leaves with between 100 and 200 needles each were collected from three different sun and shade shoots, respectively, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, before pigments were isolated as described above.

2.2.11 Rapid light curves

Fluorescence derived rapid light curves were recorded from 13 to 14 sun and shade leaves each from three different sun and shade shoots with an Imaging PAM (Walz, Germany) after 45 min of dim light acclimation by applying fifteen steps of increasing light intensity up to 1900 μmol m−2 s−1 with a respective duration of 30 s at 470 nm. After the final light step, 3 min of darkness were applied in order to follow NPQ recovery. The leaves were covered with a glass plate in order to provide sun and shade leaves with the same light intensities and incident angles. Leaves were illuminated on the adaxial side. Before the onset of the actinic light and during each rapid light curve, an 800 ms pulse of 3600 μmol photons m−2 s−1 was applied to determine the maximum fluorescence levels Fm and Fm′, respectively. Maximum relative electron transport rates (rETRmax) and other photosynthetic and photoprotective parameters were obtained by fitting the obtained fluorescence values according to Eilers and Peeters (1988) and Serodio & Lavaud (2011). The power of combining both fittings is that photosynthetic and photoprotective parameters can directly be compared from the same sample. An example of how the curves looked like, how the fitting was overlaid and how the respective values were determined can be found in the supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table S1.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Morphology and anatomy of sun and shade leaves

The linear, single veined needle leaves of A. alba are inserted helically at the shoot axis. They have a broad disk-shaped base, a distinct petiole and mostly an emarginated leaf tip. With 0.9 mm the internode length at sun exposed branchlets is about ¼ shorter compared to the situation at shaded branchlets with internodes about 1.2 mm long.

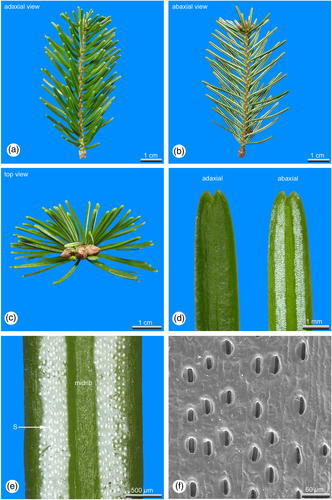

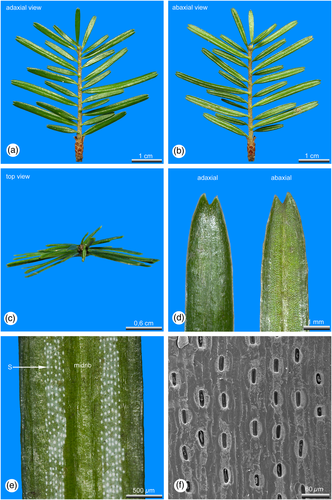

The arrangement of the lamina differs significantly between sun and shade leaves. At light exposed shoot axes, the lamina of the inserted leaves is orientated towards the upper light exposed part of the shoot axes, where they are crowded and distantly spreading from each other (Figures 1a-c). Leaves at shaded shoots are arranged distichously in two flattened rows (Figures 3a-c).

Sun leaves are distinctly longer and thicker than shade leaves (Tab. 1). Within an annual growth unit sun leaves are more or less similar in size and shape (Figures 1a, b). Only leaves at the shoot base, which are representing the inner bud scales and leaves distally below the hibernating bud, which are leading over to the outer bud scales, are significantly smaller (Figures 1a, b). However, shade leaves show a significant dimorphism in their length and can be roughly grouped in two size classes (Tab. 1). At shaded shoot axes short and long leaves are alternating to each other (Figures 3a, b) avoiding overlaps of the laminas.

| leaf type | ||

|---|---|---|

| Trait | sun | shade |

| General traits | ||

| Arrangement at the shoot axis | 3-dimensional, spreading | 2-dimensional, distichous |

| Leaf dimorphism | – | X |

| Mean internode length (mm) | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Mean leaf area (mm2) | 4.3 (± 0.09) | 3.3 (± 0.08) |

| Mean leaf length (cm) | 2.5 (± 0.05) | 1.3 (± 0.06) |

| Mean leaf width (mm) | 2.1 (± 0.02) | 1.9 (± 0.02) |

| Mean leaf thickness (mm) | 0.4 (± 0.011) | 0.2 (± 0.002) |

| Mean leaf fresh weight (g) | 0.0136 (± 0.0005) | 0.0066 (± 0.0002) |

| Mean leaf dry weight (g) | 0.0064 (± 0.0002) | 0.0027 (± 0.00009) |

| Cuticle | ||

| Thickness of the adaxial cuticle (μm) | 7.7 (± 0.367) | 4.2 (± 0.217) |

| Stomata | ||

| Adaxial | few (near the tip) | – |

| Abaxial | X | X |

| Development | deeply sunken | weakly sunken |

| Number of abaxial stomatal rows | 10–20 | 6–12 |

| Mean number of stomata (cm2) | 133 (± 2.553) | 93 (± 3.873) |

| Length of the stomium (μm) | 34.9 (± 0.260) | 31.3 (± 0.292) |

| Leaf tissues | ||

| Epidermis | ||

| Epidermis adaxial (μm) | 23.5 (± 1.063) | 18.8 (± 0.442) |

| Epidermis abaxial (μm) | 24.5 (± 1.083) | 17.5 (± 0.407) |

| Hypodermis | X | – (X) |

| Mesophyll | dimorph | monomorph or dimorph |

| Palisade parenchyma | ||

| Mean number of cell rows | 2–3 | – (1) |

| Mean thickness (μm) | 131.7 (± 5.517) | 47.3196 (± 1.608) |

| Spongy parenchyma | ||

| Mean thickness (μm) | 214.4 (± 9.978) | 233.9 (± 5.847) |

| Intercellular spaces | few | many |

| Vascular bundle strand | ||

| Endodermis | X | X |

| Diameter incl. Endodermis (μm) | 409.6 (± 9.422) | 309.8 (± 6.672) |

| Resin ducts | ||

| Number | 2 | 2 |

| Position | marginal | marginal |

Shade leaves are strictly hypostomatic. In sun leaves also a few stomata are irregularly scattered adaxial close to the tip, the majority, however, is developed abaxial in two stomatal bands, each consisting of 5–10 (sun leaves) or 3–6 (shade leaves) rows of stomata. The two stomatal bands are separated from each other by a distinct midrib. The stomata density of sun leaves is about 1/4 higher compared to shade leaves (Tab. 1). In sun leaves stomata are deeply sunken in the epidermal layer, forming crater-like depressions (Figure 1f). In shade leaves stomata are more or less in the same plane with the epidermal layer (Figure 3f). With about 34.9 μm in average, stomata of sun leaves are slightly longer than those developed in shade leaves, showing an average length of 31.3 μm (Tab. 1).

In both sun and shade leaves the epidermis is covered with a cuticle, which is nearly twice as thick (7.7 μm) in sun leaves as in shade leaves (4.2 μm, Tab. 1). In sun leaves the abaxial stomatal bands are covered with a thick whitish cuticle, visible as two whitish stripes, while in shade leaves only the abaxial stomata themselves are covered with a dense cuticle, visible as the numerous whitish dots (Figures 3d, e).

The epidermis cells of sun and shade leaves are thick-walled, but the outside exposed cell walls are slightly thicker than the internal. The entire epidermial layer in sun leaves is about 1/3 thicker than in shade leaves (Tab. 1).

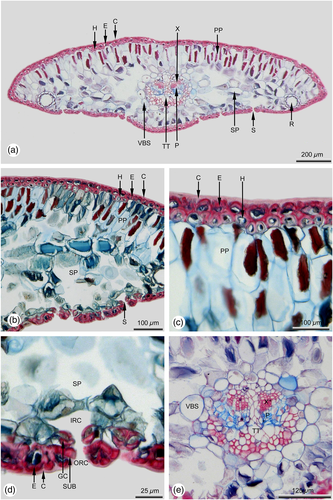

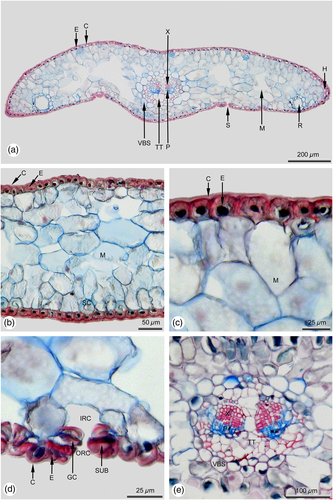

In sun leaves a distinct hypodermis consisting of strongly sclerified cells is developed below the epidermis (Figures 2a-c), a feature that is mostly absent in shade leaves. If at all in shade leaves a hypodermis is developed, it consists of only a single cell layer located at the leaf margin (Figure 4a).

The subsequent mesophyll is strictly dimorphic in sun leaves and can be subdivided into adaxial multi-layered palisade parenchyma and abaxial spongy parenchyma (Figures 2a, b). In shade leaves the mesophyll is mostly monomorphic (Figures 4a, b), or only weakly dimorphic. If it is dimorphic, only a single cell layer of palisade parenchyma is formed.

In sun and shade leaves there are two resin ducts, similar in size and shape (Figures 2a, 4a). In both leaf types they are in a marginal position, bordering on the adjacent abaxial hypodermal layer. The resin duct sheath consists of parenchymatic, non-lignified cells. The size and shape of cells forming the resin duct sheath is strongly varying even within the same sheath. The inner resin duct epithelium is also single layered and thin-walled.

The needle leaf is supplied with a single collateral vascular bundle strand that is surrounded by a bundle sheath. In sun leaves the diameter of the vascular bundle strand is about 1/4 larger compared to shade leaves (Tab. 1). Within sun and shade leaves the vascular bundle is surrounded by a vascular bundle sheath, consisting of parenchymatic, non-lignified cells (Figures 2e, 4e). Within the bundle strand, the xylem is located towards the adaxial and the phloem towards the abaxial side (Figures 2a, e, 4a, e). In both leaf types the transfusion tissue is well developed. The amount of vascular sclereids in sun leaves (Figure 2e) is distinctly higher than in shade leaves (Figure 4e). In the middle part of the leaf, a strongly developed parenchyma divides the bundle strand into two halves (Figures 2e, 4e).

A detailed overview about the foliar features of sun and shade leaves is summarized in Table 1.

3.2 Photosynthetic and photoprotective properties of sun and shade leaves

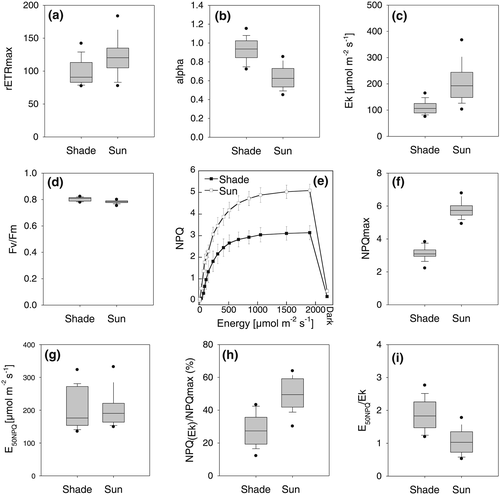

The maximum relative photosynthetic electron transport rates (rETRmax) were significantly higher in sun leaves than in shade leaves (Figure 5a). Note that due to the different excitation light wavelengths of the Imaging PAM (blue light with 470 nm) compared to field light conditions the absolute values of all following parameters referring on light intensity only serve as a rough proxy, and we will instead specifically focus on the relative comparison of sun and shade leaves. As expected, the increase of rETRmax in sun leaves was paralleled by a significant reduction of alpha, the initial increase of the slope of the ETR vs energy curve (Figure 5b). Ek increased by more than 80% in sun leaves (Figure 5c), while Fv/Fm (the maximum efficiency of photosystem II) was very similar between sun and shade leaves, at around 0.8 (Figure 5d). This highlights that sun leaves, despite being exposed to very high light intensities for a long period, did not suffer from photoinhibition. One of the major mechanisms to avoid photoinhibition is NPQ (Demmig-Adams & Adams, 2006; Goss & Lepetit, 2015; Niyogi & Truong, 2013). Indeed, the capacity for NPQ was about 90% higher in sun leaves than in shade leaves (Figures 5e, f). Importantly, it almost completely recovered within three minutes of darkness, indicating that this NPQ capacity is the fast inducible, so called energy dependent qE type quenching. Interestingly, the light intensity at which the half maximum NPQ capacity was reached (E50NPQ) was not significantly different between sun and shade leaves (around 200 μmol photons m−2 s−1, Figure 5g). NPQ at Ek, i.e. how much of the NPQ mechanism is switched on when photosynthesis already becomes saturated, was much higher in sun leaves than in shade leaves (Figure 5h). Finally, the light intensity at which NPQ reaches its half capacity compared to the light intensity when photosynthesis starts to become saturated was approximately twice as high in shade leaves as in sun leaves (Figure 5i).

3.3 Differences in the pigment composition of sun and shade leaves

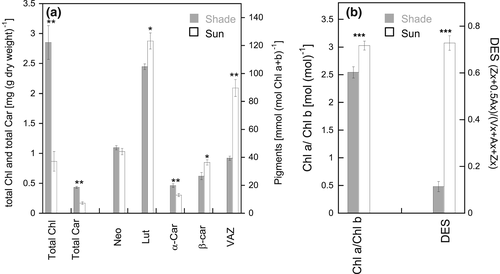

The clear differences in NPQ capacity between sun and shade leaves prompted us to investigate their pigment composition. First of all, huge differences were recorded in the total chlorophyll (Chl a + Chl b) and total carotenoid amount per dry weight leaves, with shade leaves possessing threefold more chlorophylls and 2.5fold more carotenoids than sun leaves (Figure 6a). This leads to a weight ratio of total chlorophylls vs total carotenoids of 6.6 in shade leaves and of 5.1 in sun leaves. Also, sun leaves contained significantly less Chl b per Chl a than shade leaves (Chl a/b ratio in sun leaves of around 3 vs around 2.5 in shade leaves, Figure 6B). The pool size of the violaxanthin cycle was largely different, with sun leaves having more than twice as many xanthophyll cycle pigments (VAZ) than shade leaves per total chlorophyll (Figure 6a). Importantly, in sun leaves a large part of the VAZ pigments was in the deepoxidised form (antheraxantin and zeaxanthin), i.e. in a deepoxidation state (DES) of over 0.7, compared to a DES of around 0.1 in shade leaves (Figure 6b). Finally, significant differences between sun and shade leaves in the amount of lutein (Lut, more in sun leaves), α-carotene (α-Car, less in sun leaves) and β-carotene (β-Car, more in sun leaves) per total chlorophyll were detected. Lutein epoxide was absent in sun leaves but identified in small amounts (2–6% of lutein) in shade leaves (supplemental Figure 2) and is included in the total lutein amount indicated in Figure 6a.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Sun and shade leaves show different morpho-anatomical traits

The results clearly demonstrate that also in conifers distinct morpho-anatomical differences between sun and shade leaves exist. Most of them correspond perfectly to the situation in “classical” sun and shade leaves of angiosperms (Gratani, Covone, & Larcher, 2006; Marques et al., 1999; Onwueme & Johnston, 2000), e.g. sun leaves possessing a higher leaf thickness and mass, a higher stomatal density, multi-layered palisade parenchyma and weakly developed spongy parenchyma. However, the situation in sun leaves of A. alba differs in one major point: Typically, the leaf size of especially evergreen plants - angiosperms and gymnosperms as well - growing under xeric conditions is characterized by a strong leaf reduction as a morphological response to reduce the water loss via the lamina in times of water deficit (Blum, 1996; Blum & Arkin, 1984; Bosabalidis & Kofidis, 2002; Dörken & Parsons, 2016, 2017; Dörken, Parsons, & Marshall, 2017; Parsons, 2010; Seidling, Ziche, & Beck, 2012; Thoday, 1931). Thus, in light exposed parts of the crown strongly reduced leaves were expected also for A. alba. However, sun leaves in A. alba are significantly larger than shade leaves (Tab. 1).

4.2 Sun leaf arrangement leads to self-shading

Sun leaves are more or less monomorphic in size and shape. The leaves are inserted helically at the shoot axis, but their arrangement depends strongly on their light exposure as Sprugel, Brooks, and Hinckley (1996) also showed for A. amabilis. At light exposed shoot axes the lower leaves turned upwards and are crowded on the upper side of the shoot axis. This leaf arrangement might be a possible adaption to high solar radiation occurring in the light exposed parts of the crown and could be understood as an effective protection from water loss via the lamina and protection from chlorophyll by high UV-radiation. Due to this arrangement the leaves are shading each other at lower light incident angles, while at high light incident angle (e.g. at zenith when highest intensities are reached) only the leaf tips are hit by strong direct solar radiation, while the laminas are mostly exposed to weaker diffuse lateral radiation. Thus, an exposure of the lamina to direct solar radiation occurs only for a short period each day, mostly at times of low solar altitudes in the morning and in the afternoon. This idea is supported by the fact that the change in the leaf arrangement at the shoots occurring under different light regimes within a crown is not abrupt. Within a crown it changes gradually and is accompanied by several transitional forms from light exposed to shaded parts (e.g. Cescatti & Zorer, 2003; Sprugel et al., 1996). In summary, this might be a possible explanation why in A. alba sun leaves are not reduced in size and are even significantly longer than shade leaves. If sun leaves would be strongly reduced in size, the shading effect, as described above, gets lost, and more laminar surfaces would be freely exposed to direct solar radiation, leading to an increased transpiration rate. However, this idea needs further investigations.

4.3 Shaded shoots exhibit leaf dimorphism

Shade leaves are strongly dimorphic, forming two size classes, a feature unusual for angiospermous shade leaves. The distinct leaf dimorphism and the alternating arrangement of short and long leaves can be explained to avoid an overlapping of lamina surfaces which would lead to further shading in parts of the crown, where light intensity is generally strongly reduced. This arrangement of shade leaves is quite remarkable because the alternating longer and shorter leaves are not subsequent members within the same parastichy, but are developed in an irregular ontogenetic sequence. The perfect alternation of long and short leaves within the two distichous rows at a shoot axis is achieved by incurved petioles. The developmental program deciding which leaves within a single parastichy becomes elongated and which remains short is not yet understood and needs urgently further ontogenetic investigations.

4.4 Stomata density and shape differs between sun and shade leaves

As typical for sun leaves (Abrams & Kubiske, 1990; Ashton & Berlyn, 1992; Dengler, 1980; Givnish, 1988; Lichtenthaler et al., 1981; Marques et al., 1999; Onwueme & Johnston, 2000), also in A. alba the density of stomata is significantly higher than in shade leaves. While in A. alba shade leaves are exclusively hypostomatic, in sun leaves also adaxial stomata scattered close to the tip are common. The increased density of stomata leads not only to higher rates in gas exchange but also to an increased water loss via the opened stomata. To reduce this stomatal water loss, the stomata are deeply sunken in the epidermis of sun leaves of A. alba. Furthermore, their wax coating is massive, abaxial visible as two distinct longitudinal whitish stripes, marking the parts where stomata are developed in longitudinal rows. In shade leaves, the stomata are only weakly sunken, mostly freely exposed to the airflow and only weakly covered with waxes.

4.5 A well-developed hypodermis protects sun leaves from high solar radiation

For angiosperms it could be shown that the transpiration rate of sun leaves is three to ten times higher than in shade leaves (Shields, 1950). The water loss via the lamina can be reduced by the formation of a dense cuticle but also by the formation of a thick walled epidermal layer, both features distinctly realized in sun leaves of A. alba. In addition, sun leaves have a well-developed hypodermis forming a closed ring, consisting of 2–3 layers of strongly lignified cells, which is only interrupted by the respiratory chambers of the stomata. Such a strong hypodermal layer keeps sun leaves in shape even in times of drought, when the turgor pressure decreases. In addition, the hypodermis may bring palisade cells deeper in to the mesophyll with more water between palisade cells and leaf surface. This may reduce thermic load for fully sun exposed leaves, in the same way as an orientation of the laminas that are not oriented at right angle to the radiation during the hottest phase of the day.

In shade leaves such strong protection from high solar radiation, in particular from an uncontrollable water loss via the lamina, is not needed, thus the cuticle and the epidermal layer are only thin and the hypodermis, as a stabilizing structure, usually is lacking. These findings fit quite well to those of Ashton and Berlyn (1992) who investigated sun and shade leaves of Shorea. For this angiospermous taxon they could clearly show that the epidermal cell dimensions and also the cuticle increase from shade to sun leaves, similar to the situation in A. alba. In addition to its stabilizing function, the presence of a distinct hypodermal layer may also serve as a possible protection of the mesophyll from high solar radiation, in particular from ultraviolet radiation. This hypothesis is supported by the results of Jordan, Dillon, and Weston (2005) who suggested high solar radiation as one of the drivers leading to the evolution of highly scleromorphic leaves within Proteaceae, by protecting the photosynthetically active leaf tissues from excess solar radiation and by increasing the path which solar radiation has to pass. This is a further argument for the absence of a hypodermis in shade leaves of A. alba.

4.6 The position of resin ducts is equal in sun and shade leaves

Between different Abies species the position of resin ducts varies strongly and two types can be found: marginal vs median (Andersen, Cordova, Sørensen, & Kollmann, 2006; Dallimore & Jackson, 1966; Debreczy & Rácz, 1995, 2011; Dörken, 2015; Farjon, 1990, 2010; Krüssmann, 1983; Liu, 1971; Panetsos, 1992; Rehder, 1967; Wu & Hu, 1997). However, the position of resin ducts does not only vary among the different species, but also within a tree - marginal resin ducts in leaves develop in lower parts of the crown, median ones in distal parts (Debreczy & Rácz, 2011; Gaussen, 1964; Panetsos, 1992; Roller, 1966). Roller (1966) suggested that the resin duct position is not affected by neither elevation and latitude nor by gradually changing microclimatic conditions existing between shaded basal and sun exposed distal parts of the crown. Roller assumed these changes to be caused by aging of the needles and the trees, which is supported by the fact that among his investigated taxa significant differences between juvenile (marginal position of resin ducts) and adult (median position of resin ducts) trees existed. Among adults, however, the position was more or less similar to each other. This finding fits quite well to our results, showing an abaxial marginal position of resin ducts in both sun (Figure 2a) and shade leaves (Figure 4a), which clearly demonstrates that the position of resin ducts is not a response to different light exposures.

Taken all this together, the morpho-anatomical adaptations to the high solar radiation of sun leaves resemble those of plants occurring under xeric conditions, e.g. showing a dense cuticle, strongly thick-walled epidermis cells, the presence of a hypodermis or other sclerenchymatic tissues, and encrypted stomata, while the adaptations of shade leaves, however, correspond quite well to the situation in drought intolerant plants, showing a weakly developed or absent cuticle, thin-walled epidermis cells, a low level or absence of sclerenchyma and exposed stomata (e.g. Torrey & Berg, 1988; Hill 1998; Dörken & Parsons, 2016, 2017; Dörken et al., 2017). These results are very similar to the situation in angiosperms (e.g. Ashton & Berlyn, 1992; James & Bell, 2000; Lichtenthaler et al., 1981).

4.7 The pigmentation of sun and shade leaves of A. alba follows classical patterns for sun and shade leaves in plants

The much higher amount of xanthophyll cycle pigments in sun leaves compared to shade leaves (referred on total chlorophyll) is in line to results obtained from other conifers (Adams, Demmig-Adams, Rosenstiel, Brightwell, & Ebbert, 2002). Different to the study of Adams et al. (2002) but in accordance with Lichtenthaler et al. (2007), we observed a significant alteration in the chlorophyll a to b ratio in sun and shade leaves. All in all and as the morpho-anatomical features, the pigment data fit surprisingly well to those from several angiosperm sun and shade leaves obtained in comprehensive studies by Thayer and Björkman (1990) and Demmig-Adams (1998). Both, sun leaves of A. alba and sun leaves of angiosperms contain a higher Chl a/b ratio, an increased pool of xanthophyll cycle pigments, a higher amount of β-carotene, a lower amount of α-carotene and a higher amount of lutein, while the content of neoxanthin is not changing. In fact, neoxanthin is the only pigment which is always stable in the plant kingdom, independent of changing environmental conditions (Esteban et al., 2015). Also in agreement to published data is the lower amount of total chlorophylls and carotenoids in sun leaves per leaf dry weight (Adams et al., 2002; Demmig-Adams, 1998; Lichtenthaler et al., 2007; Lichtenthaler & Buschmann, 2001). Finally, the weight ratio of total chlorophylls to total carotenoids in sun (5.1) and shade (6.6) leaves of A. alba lies exactly in the range known for sun (4.3 to 5.7) and shade leaves (5.4 to 7) of plants in general (Lichtenthaler & Babani, 2004). These results suggest that changes in pigmentation of sun and shade leaves in the growing season are universal among the land plant kingdom and independent of leaf type.

Two facts are additionally noteworthy: First, lutein epoxide was identified in A. alba. This pigment is often not highlighted in published pigment analyses, probably because of its relatively low amounts (in our case only 2–6% compared to lutein), but its presence has been verified in 80% of investigated gymnosperms and also in different Abies species (Czeczuga, 1986; Esteban et al., 2009). The existence of lutein epoxide especially in deep shaded canopies is in line with our findings (García-Plazaola, Matsubara, & Osmond, 2007; Matsubara et al., 2009). There is experimental evidence that lutein epoxide is a more effective light harvesting pigment than lutein (Matsubara, Morosinotto, Osmond, & Bassi, 2007).

Secondly, the amount of lutein per chlorophyll did not decrease in sun leaves, but even slightly increased compared to shade leaves. Lutein and zeaxanthin have very similar retention times during an HPLC run, but we could reliably separate both pigments (see supplemental Figure 2). Indeed, pigment surveys of many different species indicate that similar or even higher amounts of lutein per chlorophyll in sun leaves are common across the plant kingdom (Demmig-Adams, 1998; Esteban et al., 2015; Matsubara et al., 2009; Thayer & Björkman, 1990). Besides its involvement in light harvesting, a possible role of lutein in NPQ is still under debate. It is assumed, however, that its most important function is the quenching of triplet chlorophyll under light stress where lutein proved to have superior capacities compared to all other carotenoids occurring in the light harvesting complexes (reviewed by Jahns & Holzwarth, 2012). Hence, high amounts of lutein in sun leaves are in line with its function. However, lutein is considered to be bound to the antenna complexes (LHCII and LHCI) which also bind the Chl b molecules (Morosinotto, Caffarri, Dall'Osto, & Bassi, 2003). As in sun leaves Chl b is reduced, one must also assume a decrease in the amount of antenna proteins (especially the Chl b rich PSII antenna proteins), which indeed has been shown e.g. in radish (Lichtenthaler, Kuhn, Prenzel, Buschmann, & Meier, 1982) and Arabidopsis (Kouřil, Wientjes, Bultema, Croce, & Boekema, 2013). However, the different Lhc proteins have three to four xanthophyll binding sites, which may be occupied by different xanthophylls (Morosinotto et al., 2003). Moreover, the Chl a/b ratio varies between the major LHCII proteins forming trimers and the minor monomeric antenna proteins CP24, CP26 and CP29. E.g., CP29 has a higher Chl a/b ratio than the LHCII trimer (Liu et al., 2004; Morosinotto et al., 2003), and this protein is relatively upregulated in Arabidopsis plants acclimated to long lasting high light conditions (Kouřil et al., 2013). Also, lutein is usually much more enriched than Chl b in so called “free pigment fraction” preparations, which indicates that at least a part of the total lutein pool may be localized free in the thylakoid membrane, independent of binding to antenna proteins (Matsubara et al., 2003; Matsubara et al., 2007). This free pigment fraction is strongly increased in sun compared to shade leaves (Matsubara et al., 2007). So far, nothing is known about the stoichiometric ratios of antenna proteins as well as the distribution of lutein within the thylakoid membrane in sun and shade leave of A. alba which needs future investigations.

4.8 The photosynthetic and photoprotective performance of sun and shade leaves in A. alba exhibits unique features

The upregulation of photosynthetic capacity in sun leaves of conifers collected in summer compared to shade leaves is in line with earlier results (Adams et al., 2002; Givnish, 1988; Lichtenthaler et al., 2007). Albeit shade plants grew under quite low light intensities (10–20 μmol m−2 s−1), they still could rapidly switch on NPQ and could reach maximum NPQ values of around three. This is higher than the NPQ values usually obtained in annual plants, even when they are acclimated to sun light conditions (Adams & Demmig-Adams, 2014). Such fast and relatively high NPQ is caused because shade leaves of A. alba regularly experienced sun spots (in our case up to 250 μmol photons m−2 s−1) during the course of the day. As has been demonstrated, such sunspots are enough to keep the VAZ pool to a certain amount deepoxidised under low light/dark conditions, which then enables the leaf to rapidly switch on a pronounced NPQ upon exposure to high light (Demmig-Adams et al., 2014). Indeed, the shade leaves of A. alba exhibited a DES of around 0.1 (Figure 6B).

The combined approach of relating specific fluorescence based relative ETR and NPQ parameter has, to our best knowledge, so far not been performed in conifers. While the behaviour of single parameters as NPQmax, alpha and ETRmax are very well known for sun and shade leaves of plants and trees (e.g. Demmig-Adams, 1998; Lichtenthaler et al., 2007; Rodriguez-Calcerrada et al., 2008; Serôdio & Lavaud, 2011; Valladares & Niinemets, 2008) and corresponds to the data obtained here, other parameter show intriguing features. Compared to a meta-analysis performed on plants, mosses and microalgae (Serôdio & Lavaud, 2011), sun and shade leaves of A. alba responded differentially in the parameters E50NPQ, NPQ(Ek)/NPQmax and E50NPQ/Ek. E50NPQ, in sharp contrast to all species investigated by Serôdio and Lavaud (2011) except a seagrass, did not increase in sun compared to shade leaves of A. alba. Also, it was generally quite low, even taking into account that for measuring rapid light curves we used photosynthetically more active blue light while other studies mostly rely on white or red light. Because of the unusual stable E50NPQ value, being independent of incident light amount, and the typical increase of Ek in sun leaves, the ratio E50NPQ/Ek dropped to a value of about 1 in sun leaves, a feature not observed in angiosperm plants (Serôdio & Lavaud, 2011) and even not recorded in severely light stressed diatoms, which can build up a huge NPQ (Lepetit et al., 2017). Also the values for NPQ(Ek)/NPQmax, at about 30% in shade and about 50% in sun leaves, were largely higher than the average value for plants/algae with a violaxanthin cycle (25–75% percentile between 8 and 20% (Serôdio & Lavaud, 2011)). Hence, while at a first glance sun leaves of A. alba contain typical physiological features of angiosperm sun leaves (high photosynthesis rate, pronounced NPQ capacity, large xanthophyll cycle pigment pool, low amount of chlorophyll per leave, high chlorophyll a/b ratio, high Ek, low alpha), the comparison of ETR with NPQ derived parameters clearly shows distinct features. By calculating the easily measurable parameters E50NPQ, E50NPQ/Ek and NPQ(Ek)/NPQmax our results strengthen the statement from Demmig-Adams et al. (2014) that (tropical) evergreens cannot increase photosynthetic efficiency, but rather rely on higher photoprotection capacity in sun leaves. Apparently, sun leaves of A. alba only have a limited potential to increase their photosynthetic performance compared to shade leaves. Instead, they can adjust the capacity of NPQ, which, however, under all different light conditions is rapidly switched on already under low light conditions. We assume that such a strategy may be important for avoiding photoinhibition under prolonged light exposure. Given the very crowded needle arrangement in sun shoots and as discussed in chapter 4.2, however, one may speculate that A. alba sun leaves shade each other frequently during the change of the incident light angle over the course of the day. This hence may often lead to lower light conditions even in sun exposed shoots than stable high light conditions throughout the whole day for the individual sun leaf. Given the flexible NPQ A. alba sun leaves possess in the summer (we observed basically full recovery of maximum NPQ capacity in a 3 min dark interval), the leaves may efficiently perform photosynthesis under relative lower light conditions (i.e. due to shading of adjacent needles of the same shoot), while immediately switching on NPQ when fully exposed to the sun again. This situation is entirely different from the complete downregulation of photosynthesis due to a sustained NPQ usually observed in temperate conifers in winter (Verhoeven, 2014). Our results demonstrate a remarkable physiological and morpho-anatomical flexibility of A. alba leaves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Michael Laumann and Dr. Paavo Bergmann (Electron Microscopy Center, Department of Biology, University of Konstanz, Germany) for technical support (paraffin technique). This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. LE 3358/3-1 to B.L.) and the Baden-Württemberg Elite program (to B.L).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.