Identity, threat aversion, and civil servants' policy preferences: Evidence from the European Parliament

Abstract

Distinct policy options are typically characterized by a number of advantages (or ‘opportunities’) and disadvantages (or ‘threats’). The preference for one option over another depends on how individuals within an organization perceive these opportunities and threats. In this article, we argue that individuals' identification with an organization's core aims and objectives constitutes a key determinant of this perception. We propose that stronger identification shifts individuals' attention towards potential threats rather than opportunities in the payoff distribution, encouraging avoidance of negative outcomes. Moreover, we argue that this ‘prevention focus’ in individuals' motivational basis will be stronger under negative than under positive selection strategies. An original survey experiment with civil servants in the European Parliament finds significant evidence supporting the empirical implications of our argument.

1 INTRODUCTION

The advantages and disadvantages of distinct policy options generally become the subject of extensive deliberation and negotiation in both the private and the public sector. The outcome of such negotiations and the implementation of the ensuing decisions determine the success or failure of an organization. While the advantages of a given policy option can be viewed as ‘opportunities’ to reach favourable outcomes (e.g., high profit in the private sector, attaining educational or social welfare targets in the public or non-profit sector, etc.), the disadvantages can be perceived as possible ‘threats’ to the organization and its goals. A large literature has highlighted the role of such threat and opportunity perceptions in a variety of contexts (Jackson and Dutton 1988; and references therein). Yet, a critical subsequent question has received much less attention: What makes someone more or less likely to focus on either opportunities or threats in distinct policy proposals?1 Identifying the drivers of such opportunity-vs.-threat perceptions is critical to our understanding of the policy preferences of political actors, and lies at the heart of our analysis.

We specifically focus on the role of individuals' identification with, and dedication to, an organization's core aims and objectives—which constitutes a central element of organizational identification (Hall et al. 1970; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Scott and Lane 2000). Individuals' organizational identification has been linked to outcomes including job satisfaction, individual well-being, and risk preferences. Building on motivation theory (Atkinson 1957; Atkinson et al. 1960; Lopes 1984, 1987) and Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979), we argue that a stronger identification of individuals with their organization's goals also strengthens their motivation to avoid a policy failure. It particularly generates a ‘prevention focus’, and shifts individuals' relative attention towards potential threats rather than opportunities in the pay-off distribution. Thus, it shifts preferences towards options avoiding negative outcomes during policy decisions. This has, to the best of our knowledge, not previously been tested, and constitutes the first central novelty of this article.

The second contribution lies in assessing the role of the choice framework as a potential moderator of this shift. We maintain that an identification-driven shift in focal point towards threat avoidance is likely to arise predominantly for individuals whose (externally imposed) selection strategy consists of rejecting a least preferred option rather than choosing a preferred option. Evidence shows that a decision-maker's commitment to a selected option is at least partially dependent on the characteristics of the selection strategy used; that is, on choosing or rejecting options (Shafir 1993; Ganzach 1995; Meloy and Russo 2004). Positive selection strategies require an individual to make a firm commitment to one option, whereas negative strategies merely invite the acceptance of the least-bad option (Ganzach 1995). When faced with distinct policy options, we argue that any inherent lack of commitment within different selection strategies can be compensated at least in part by individuals' identification with an organization's core aims and objectives. The additional ‘prevention focus’ that a stronger identification generates thus is likely to matter most under negative selection strategies, where individuals' commitment to their preferred alternative is lower.

Our empirical analysis of these theoretical propositions is based on an online survey experiment among civil servants within the European Parliament (i.e., ‘Administrators’ responsible for information preparation and dissemination; N = 69). Such data obtained from public officials rather than students substantially benefit the external validity of our study (Druckman and Kam 2011; Cappelen et al. 2015; Grimmelikhuijsen et al. 2017). Furthermore, the European Parliament's administration constitutes a particularly interesting setting for two reasons. First, these officials play an important role in the internal decision-making process within the European Parliament (Neunreither 2002; Neuhold and Radulova 2006; Winzen 2011; Neuhold and Dobbels 2015). Much like Administrators in the European Commission, they have the ability to influence policy decisions through the exploitation of bureaucratic discretion (Pollack 2003; Olsen 2006; Schafer 2014) and by providing substantive guidance and support to Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) and other stakeholders (Egeberg et al. 2013). This makes them of central relevance to our study. Second, the European Parliament's staff is subject to a regular rotational system, which makes it difficult for them to develop vested interests in certain policy areas or strong (and potentially problematic) personal ties with the stakeholders involved. Any political bias that could be expected from, for instance, politicians (such as MEPs) is thus likely to be largely absent among our respondents.

We present our respondents with hypothetical, but realistic, policy scenarios, and provide two possible policy options under each scenario. The options are manipulated to reflect different valences, whereby one option presents simultaneously more threats and opportunities than the other (for a similar approach, see Shafir 1993; Ganzach 1995; Meloy and Russo 2004). Participants express their preferences for one option in each scenario under either a positive or a negative selection framework. In the former, they choose their preferred option (henceforth ‘choice frame’), whereas they reject their least favourite option in the negative framework (henceforth ‘reject frame’). We analyse how the selections depend on respondents' level of identification with organizational goals.

Our main findings indicate that stronger identification with organizational goals is associated with higher levels of threat aversion in individuals' policy preferences. This is consistent with the idea that such identification induces a ‘prevention focus’, and shifts people towards avoiding policy features that may endanger the organization's success. Furthermore, the effect of stronger identification is particularly relevant in a setting where respondents reject a least preferred option (rather than choose a preferred option). This corroborates the idea that individuals' stronger identification with organizational goals can compensate for lower feelings of commitment or responsibility for the final selection when rejecting one of two options (which need not imply a strong commitment to the remaining option). Both findings are robust to the exact operationalization of individuals' identification with organizational goals.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

An organizational identity can be defined as ‘a collectively held frame within which organizational participants make sense of their world’ (Scott and Lane 2000, p. 43). The extent to which individuals identify with, and are dedicated to, an organization's goals constitutes a central element of such organizational identities (Hall et al. 1970; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Scott and Lane 2000). Such identities and (the extent of) organizational identification are known to have important implications for individuals' preferences and behaviour.2 For instance, psychological processes inducing the internalization of the organization's aims and goals strengthen individuals' motivation to reach group goals (Kramer and Brewer 1984; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994), and make them more likely to take decisions benefiting the interests of the organization even in the absence of direct supervision (Simon 1976). Furthermore, the extent of individuals' identification with the organization and its goals ‘systematically affects individuals’ perceptions of issues' (Dutton and Penner 1993, p. 90). It ‘shape[s] interpretive predispositions that focus attention on some information and issues and exclude others’ (Gioia and Thomas 1996, p. 372). Based on these findings, it can be expected that individuals identifying more strongly with an organization and its core aims and objectives will look differently at the advantages (or ‘opportunities’) and disadvantages (or ‘threats’) embedded in distinct policy options.

This proposition can be grounded in motivation theory (Atkinson 1957; Atkinson et al. 1960; Lopes 1984, 1987), which maintains that individuals' motivation for action is determined by both a desire for success (the achievement motive) and a fear of failure (the avoidance motive). The relative strength of these counter-directional motivational tendencies governs individual-level preferences and decision-making in any given situation. They guide individuals' attention between the good and bad elements in a pay-off distribution: achievement motives induce a focus on opportunities, whereas avoidance motives prompt a focus on threats.

Importantly, as argued by Lopes (1984, 1987), situational as well as individual dispositions determine whether people award more or less attention to good or bad outcomes (or, phrased differently, whether achievement or avoidance motives take the upper hand). In our view, individuals' identification with an organization's core aims and objectives constitutes a key individual-level determinant of this shift in focus. It not only instils a desire to achieve the best possible outcome for the organization (Kramer and Brewer 1984; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994), but also prompts people to view policy issues through organization-coloured lenses (Dutton and Penner 1993; Gioia and Thomas 1996). It focuses individuals' attention on what is best—or least bad—for the organization.

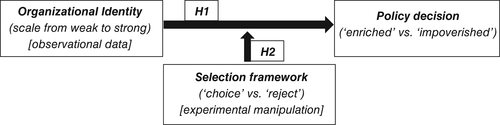

H1: A stronger identification with an organization and its goals is associated with a threat-averse selection of policy options.

Selection can in principle involve a positive strategy (i.e., choosing a preferred option) or a negative strategy (i.e., rejecting a least preferred option). These characteristics of the selection strategy can have an important effect on individuals. Shafir (1993), for instance, argues that such inconsistency with the invariance axiom of rational choice theory4 arises because individuals put more weight on the relevant advantages of a particular option when formulating reasons to choose it and on its disadvantages when formulating reasons to reject it (see also Meloy and Russo 2004). Ganzach (1995), instead, maintains that selection strategies matter because people feel more committed to, or responsible for, their selected options under a choice frame, and therefore adjust their evaluation of available alternatives. The underlying idea is that a direct rejection of something does not necessarily imply a firm commitment to the remaining option; rather, it could be seen as a choice ‘by default’. That is, ‘One has to live with the alternative [one] accepts, but not with the alternative [one] rejects’ (Ganzach 1995, p. 115). This argument would imply that more weight will be put on the relevant disadvantages of available options when formulating reasons for choosing one of them.

H2: Individuals' identification with an organization and its goals affects their choices more under negative than under positive selection frameworks.

3 EMPIRICAL APPROACH

To test our hypotheses, we ran a survey experiment with public officials in the European Parliament during the spring of 2015. In this section, we discuss, in turn, our case selection, the research design, and our empirical methodology.

3.1 Case selection

We study civil servants (‘Administrators’) working in the secretariat of the European Parliament, who play a central role in the preparation and dissemination of information throughout the Parliament's decision-making process. Within this secretariat, we focus on officials working in the Committee secretariats and information support units (i.e., policy departments). The reason is that these officials' work is linked most directly to the legislative process, making them of central relevance to our study.

The secretariats are organized around the committees of the European Parliament, each of which deals with a specific set of policy areas: for instance, the committees on Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL), Regional Development (REGI), Transport and Tourism (TRAN), etc. The majority of administrative staff work for one Committee at a time and follow a limited number of dossiers over the entire course of the legislative process. They coordinate intra- and inter-institutional meetings, act as liaison between the rapporteurs and the Commission and Council, and provide, for instance, background statistics and analyses, forecasts, policy briefings, and other information. Consequently, Administrators are often in direct contact with MEPs and other stakeholders, and provide technical and substantive guidance to them (Egeberg et al. 2013).5 Although the power of Administrators within the European Parliament may be limited by the role of the hierarchy within the institution (Winzen 2011), their ability to exploit bureaucratic discretion nonetheless provides a non-negligible influence in the policy-making process (Pollack 2003; Olsen 2006; Schafer 2014). Several studies have shown that this allows them to impact (the early stages of) the Parliament's internal decision-making process (Neunreither 2002; Neuhold and Radulova 2006; Winzen 2011; Neuhold and Dobbels 2015). In this capacity, they might affect the content of subsequent policy decisions also by pre-selecting available options based on their feasibility and potential outcomes. Such influence is most likely to occur in internal deliberations and non-formal interactions with, for instance, rapporteurs, rather than at later stages when proposals and amendments have already been formalized and passed onto political debate. The selection frame applied to such considerations may depend on the precise circumstances surrounding the issue and the stakeholders involved.6

A focus on the European Parliament offers advantages on at least three other counts. First, as mentioned above, its staff are subject to a regular internal rotation system in which individuals generally change position every three to six years. By undermining the development of strong vested interests and/or personal ties in any given policy area, this implies that political bias is likely to be weaker among our respondents (compared to, for instance, politicians). Second, with its increasing powers, the European Parliament is slowly attracting more scientific attention, but most of this developing literature concentrates on parliamentarians—not public officials (notable exceptions include Egeberg et al. 2013, 2014a, 2014b). Our explicit focus on the preferences of public officials thus helps to develop a clearer picture of the entire European legislative process. Finally, behavioural approaches and experimental methods have in recent years become more prominent in the political sciences (James 2011; James and Moseley 2014; Blom-Hansen et al. 2015; Kuehnhanss et al. 2015; Nielsen and Baekgaard 2015; George et al. 2016; Baekgaard et al. 2017), and are increasingly being introduced to the study of public administrations (Andersen and Hjortskov 2016; Andersen and Moynihan 2016; Jilke et al. 2016; Geys and Sørensen 2017; Grimmelijkhuisen et al. 2017). However, such studies have thus far only considered national or sub-national levels of government, and fail to engage with the supranational level.

3.2 Research design

To collect the required data, an online survey experiment was distributed via email within the two selected Directorates-General (DGs) of the European Parliament. Information from the European Parliament's 2015 budget indicates that about 40 per cent of its staff are Administrators, while 44 per cent are Assistants and 16 per cent are temporary staff. This implies that an estimated 360 Administrators received our survey. We obtained 69 responses from staff reporting to have Administrator contracts. Based on the shares of different contract types within the European Parliament, this would reflect a response rate of approximately 19 per cent.7 Summary statistics reflecting the composition of our sample are provided in Table 1. For privacy reasons, we were not provided with any information regarding the descriptive background characteristics of the Administrators in the participating DGs. Hence, we cannot provide a direct test of the representativeness of our sample. It is therefore particularly important to point out that the demographic composition of our sample is similar to previous reports of the European Parliament secretariats' composition (e.g., Egeberg et al. 2014a, 2014b). The reported demographic composition in these studies closely matches our sample in terms of sex, age, education, and experience, which suggests little difference along these dimensions with the population of Administrators in the selected DGs. Note, however, that compared to the selected DGs (which have the closest links to the political decision-making process), staff characteristics are likely to be different in less policy-driven DGs (e.g., due to different shares of Administrators in such DGs). Generalizations from the surveyed population to other DGs in the European Parliament or other public officials in the European Parliament may thus not be straightforward. On the political side of the decision-making process, for instance, other factors such as political constraints and bargaining may become more dominant (we return to this in our concluding discussion).

| Age | n | Gender | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26–35 | 9 | Male | 63.2 |

| 36–45 | 27 | Female | 36.8 |

| 46–55 | 24 | ||

| 56–65 | 8 | Nationalities in sample | n |

| 65 < | 1 | 18 | |

| Education | n | International study | n |

| Bachelor | 2 | None | 16 |

| Master | 46 | Up to 1 year | 22 |

| Professional degree | 3 | More than 1 year | 30 |

| PhD | 16 | n/a | 1 |

| n/a | 2 | ||

| Field of study | n | Grade | n |

| Law | 15 | AD5–AD6 | 12 |

| Economics | 14 | AD7–AD8 | 18 |

| Politics / International Relations | 25 | AD9–AD11 | 19 |

| Arts | 4 | AD12–AD16 | 13 |

| Physical Science | 5 | n/a | 7 |

| Engineering | 4 | ||

| n/a | 2 | ||

| Years in Directorate-General | Years of work for the EU | ||

| Mean | 5.04 | Mean | 9.10 |

| Min | 0 | Min | 0 |

| Max | 20 | Max | 25 |

| SD | 3.82 | SD | 7.00 |

The central part of the survey presents respondents with up to five hypothetical, but realistic, policy scenarios consisting of a policy issue and two policy proposals.8 The policy issues are based on actual policy considerations in the European institutions (sources are provided in appendix A) and relevant to broad sections of the population: that is, youth unemployment, renewable energy, transport policy, cultural and language policy, and the rehabilitation of industrial areas. By covering a range of different and unrelated topics, we reduce the probability that unique policy aspects drive our respondents' choices across scenarios. Even so, we cannot exclude the possibility that particular features of the selected contexts differentiate them from other policy issues. With regard to testing our hypothesis, however, these topics provide an ideal basis as they are relevant enough to the European Parliament (otherwise no resources would have been spent on the studies listed in appendix A), but not so politically entrenched as to no longer engender debate.

The two policy proposals presented to respondents for each policy issue consist of short statements on five key attributes of the policy at hand. To operationalize the opportunities and threats embedded in the distinct policy proposals, we differentiate both proposals via the combination of attributes with different valences (Shafir 1993; Ganzach 1995; Meloy and Russo 2004). In one policy proposal (henceforth, ‘impoverished’), all five attributes are formulated as neutrally as possible. Any outcomes are thus described as ‘average’, or are constructed not to provide any particular positive or negative associations. This impoverished policy option constitutes a ‘baseline’ reference point against which respondents would evaluate the other policy proposal. In the second policy proposal (henceforth, ‘enriched’), two attributes are formulated as very positive (reflecting the opportunities provided by this option), two are formulated as very negative (reflecting the threats posed by this option), and one remains neutral. A detailed example is provided in Table 2. Note that the positive attributes in the enriched proposal provide reasons for choosing it, but the negative attributes correspondingly offer reasons for rejecting it (Shafir 1993). This is important for our purposes, because it implies that an individual's relative focus on these positive/negative attributes will influence his/her final choice. We expect individuals' identification with an organization's goals to play a key role in determining this relative focus.

| Imagine that two proposals to mitigate youth unemployment in southern Member States have emerged. Some of their expected outcomes are briefly sketched below. You are part of a working group tasked with their evaluation. [Which one do you choose to support? / After intense discussions on both proposals, you are only able to concentrate on one of them. Which proposal do you NOT support further?] | |

|---|---|

| Proposal 1 | Proposal 2 |

| (o) Fund managers have normal rapport with project leaders; sometimes good, sometimes bad | (+) Fund managers have very good rapport with the project leaders, which benefits the projects |

| (o) Mixed results for the effectiveness of the funds for the target group (i.e., young people) | (+) Very effective use of the dispersed funds for the target group (i.e., young people) |

| (o) Projects need to apply individually either to the national agency or the supranational organization | (o) Projects need to apply individually either to the national agency or the supranational organization |

| (o) Average bureaucratic costs with most funds remaining available for projects | (−) High centralized bureaucratic cost reducing the amount allocated for projects |

| (o) Average progress with most help arriving at the projects in a reasonable amount of time | (−) Slow progress due to difficulties in finding good projects without knowledge of local conditions |

- Notes: In the choice frame only the first part in square brackets is presented, in the reject frame only the second part. Denotation of valences: (o) neutral; (+) positive; (−) negative.

After reviewing them, participants are requested to make a decision between both available policy proposals. This decision requires them—depending on the task frame—to either select their preferred proposal (the choice frame) or to reject their least preferred proposal (the reject frame). This selection is our central dependent variable in the analysis below.

Before the start of the survey each respondent is randomly assigned to one of seven versions. Each version contains different combinations of the frames and presents the hypothetical policy scenarios in a varying order to minimize ordering effects. Four versions contain only the choice or reject frames, and the remainder include both choice and reject frames. In total, 188 people opened the survey invitation (which triggered the randomization), and 102 individuals completed the survey. Anecdotal evidence from conversations with European Parliament staff suggests that most of this drop-out was due to Assistant-level staff judging the tasks presented to be not relevant to them. Sixty-nine of the completed surveys are from Administrator level staff with policy competences, which are of central interest to our analysis. All responses submitted by Administrators are included in the analysis.9 As we observe no systematic differences between their answers across the different survey versions, we pool the responses and include version dummies throughout the empirical analysis to avoid any potential bias in our results. The research design here thus reflects a combination of a between-subjects design (i.e., when comparing different respondents' answers in the choice and reject frames) and a within-subjects design (i.e., when comparing the same respondents' answers across choice and reject frames in the mixed-frame versions of the survey).

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of our research design and its link to our central hypotheses. Key variables in our theoretical argument are presented in boldface, with their operational variation in the empirical design indicated in parentheses. Further methodological information is provided in square brackets.

3.3 Empirical methodology

(1)

(1)A first set of questions therefore enquires into respondents' preferred distribution of decision-making power in the European Union as an issue of sovereignty (i.e., the authority over a given policy) (taken from Kassim et al. 2013; Schafer 2014; Murdoch et al. 2017). EU-level decision-making as an issue of sovereignty remains high on the political agenda (Murdoch 2012; Hobolt 2014; Murdoch and Geys 2014), which allows us to operationalize the extent to which someone favours European over national decision-making power. The question employed in the survey reads: ‘What is your position on the distribution of authority between member states and the EU on public policies? Please indicate on an 11-point scale with “0” (exclusively national) to “10” (exclusively EU) where, in your opinion, this policy should be decided (which may, or may not, differ from where it currently is decided).’ This question was asked for 13 policy areas, and the average response for all of them is our first measure of respondents' identification with the European Parliament's goals (EU_Power).10

A second set of questions asks about the emphasis respondents feel should be put on ‘common/overall EU concerns’ and the ‘best interests of my home country’ in their day-to-day work (taken from Murdoch and Trondal 2013).11 Responses are coded on a 5-point scale with higher numbers reflecting stronger emphasis on a particular set of concerns. Clearly, social desirability is likely to induce our specific respondent sample to express stronger emphasis for EU rather than national interests. Even so, the difference between their answers on both questions can nonetheless provide a valid indication of respondents' relative attachment to the EU versus their home country (Murdoch and Trondal 2013; Trondal et al. 2015). Consequently, this difference represents our second measure of respondents' identification with the European Parliament's goals (EU_Concerns). Summary statistics for our dependent variable and the measures for OrgID i are provided in Table 3.12

| Selected options and Frame | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable (Yit) | n | Frame | % |

| Enriched option | 113 | Choice | 52.3 |

| Impoverished option | 172 | Reject | 47.7 |

| Identification with the organization's goals (OrgID) | |||

| EU_Power (11-pt scale) | EU_Concerns (5-pt scale) | ||

| Mean | 6.79 | Mean | 2.68 |

| Median | 6.92 | Median | 3.00 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.25 | Standard Deviation | 1.09 |

(2)

(2)The key parameter of interest in equation 2 is δ , which indicates to what extent the effect of identifying with the organization's goals differs across both frames. Support for H2 requires that δ > 0, which would imply that any negative effect of identification (as predicted under H1) is indeed stronger when individuals reject their least preferred option (i.e., Frame = 0) rather than choose their most preferred option (i.e., Frame = 1).13

Throughout all estimations, we include control variables for each of the specific policy issues presented to respondents and for the version of the survey to which respondents are randomly allocated. These account for any possible heterogeneity in selection decisions specific to the policy area or survey version. Although not really required when relying on experimental data (assuming successful randomization), we also experimented with additional controls for individuals' age, gender, nationality, educational background (i.e., highest degree, field of study and education abroad), grade and length of work in the European institutions as well as in the current position (see Table 1). As there are too many nationalities with too few observations per country in our sample, we combine them into three different Regions: Eastern Europe, Northern Europe, and Central and Southern Europe. Corroborating the success of our random allocation of respondents, these background variables are generally statistically insignificant and are therefore not retained in the final model (with the sole exception of respondents' field of study). Still, to illustrate that our results are not determined by the exclusion of specific controls, Table OA.3 in the online appendix presents a set of results with the controls included.

4 RESULTS

(3)

(3)| EU_Power | EU_Concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection of the enriched option | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Frame | 0.520 | 0.123 | 0.123 | 0.548 | 0.133** | 0.133** |

| (0.232) | (0.193) | (0.193) | (0.255) | (0.116) | (0.116) | |

| OrgID i | 0.811** | 0.725** | 0.835 | 0.592** | ||

| (0.085) | (0.116) | (0.107) | (0.135) | |||

| OrgID i * Frame | 1.242 | 1.686* | ||||

| (0.287) | (0.478) | |||||

| OrgID i * Reject | 0.725** | 0.592** | ||||

| (0.116) | (0.135) | |||||

| OrgID i * Choose | 0.901 | 0.998 | ||||

| (0.139) | (0.153) | |||||

| Field of study dummies | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Question dummies | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Condition dummies | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| n of selections made | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 | 285 |

| Pseudo-R2 | .115 | .095 | .117 | .112 | .094 | .121 |

- Notes: Logistic regression models with standard errors clustered at the level of the individual respondent in parentheses; reported values are odds-ratios;

- * p < .10,

- ** p < .05,

- *** p < .01. The dummy variable Frame is 0 for Reject and 1 for Choice. The Question and Condition dummies control for order- and question-specific effects. They are omitted from the table for clarity. EU_Power = Average across the 13 autonomy questions; EU_Concerns = EU concerns – Home concerns questions.

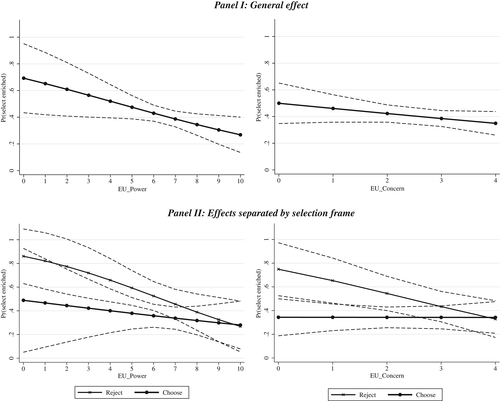

The results in Table 4 provide substantial evidence in support of hypothesis H1. Indeed, the estimated odds ratio for OrgID i is smaller than 1, and statistically significantly different from 1 at conventional levels in column (1). The same is observed in column (4), although the estimate fails to reach statistical significance in this case. Overall, these results suggest that the probability of selecting the enriched option (relative to the probability of not selecting it) decreases by 16 to 19 per cent for each unit increase in individuals' identification with the European Parliament's goals. For an arguably more accessible graphical representation of these results—expressed in terms of the predicted probability of selecting the enriched option—see the top panel of Figure B1 in the appendix. These findings are in line with our argument that stronger identification induces a ‘prevention focus’ in individuals' motivational basis. Such identification generates a preference for the average/neutral policy proposal, and the avoidance of policy proposals that carry potential threats.

Columns (2) and (4) indicate that the estimated odds ratio on the interaction term Frame * OrgID i is larger than 1—in agreement with hypothesis H2—but remains statistically insignificant. This provides some initial evidence in line with the idea that the effect of identifying with an organization's core goals is stronger for a negative selection framework than for a positive selection framework. Yet, the exact effects of identification in the choice and reject frames can be evaluated more readily based on the results in columns (3) and (6), where the effect of organizational identification is split by Frame.14 This shows that the effect of identification in the choice frame is statistically insignificant. Its effect on respondents in the reject frame, however, is statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level. It is also substantively large in this case. The estimated odds ratio indicates that the probability of selecting the enriched option in the reject frame (relative to the probability of not selecting it) decreases by 29 to 41 per cent for each unit increase in individuals' identification with the European Parliament's goals. A graphical representation is provided in the bottom panel of Figure B1 in the appendix. Overall, the effect of identification appears to be contingent on the decision-making frame provided to respondents. This is in line with hypothesis H2, which states that identification with an organization and its goals is more important under negative than under positive selection strategies. A higher level of identification may act as a substitute for the commitment felt under a positive selection strategy, encouraging the rejection of options perceived as carrying a threat to the organization.15

5 CONCLUSION

This article provides empirical support for the idea that individuals' identification with an organization and its core aims and objectives guides their opportunity-vs.-threat focus in situations where distinct policy proposals are characterized by advantages and disadvantages. Our behavioural perspective on individual-level policy preferences advances the understanding of organizational decision-making in several ways.

From a theoretical perspective, our analysis brings forward individuals' organizational identification as a dispositional characteristic underlying preference-formation in an institutional context. Previous research has extensively documented how organizational identification influences, for instance, individuals' motivation (Kramer and Brewer 1984; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994) and their issue perceptions (Dutton and Penner 1993; Gioia and Thomas 1996). We contribute to this literature by arguing that identification impacts individuals' policy preferences by shifting the relative focus on the advantages and disadvantages of available policy options. We thereby likewise contribute to the integration of behavioural elements into the analysis of policy-making, which has recently received increased attention (James 2011; Andersen and Moynihan 2016; Riccucci et al. 2016; Geys and Sørensen 2017; Grimmelikhuijsen et al. 2017; Olsen 2017).

From a policy perspective, our results suggest that strategic manipulation of the positive/negative valence of various policy proposals under consideration, or imposing selection under choice/reject frames, can have an important influence as early as the preparatory policy-making phases. Clearly, this is likely to have implications also for later stages in the policy design and implementation (e.g., because some options will simply no longer be on the table at later stages).16 Importantly, such an effect is independent of the further influence of similar strategic accentuation of the (dis)advantages of certain options—for instance, by labelling them as ‘threats’ and/or ‘opportunities’ (Dutton and Jackson 1987; Gioia and Thomas 1996)—at later stages of the decision-making process. As such, our results highlight the importance of carefully considering the decisions taken (and selection structures imposed) at different stages of a policy-making process to avoid undue sources of decision bias.

Finally, we contribute to experimental work on organizational decision-making by relying on data obtained from actual public officials rather than students. Moreover, our policy scenarios derive from analyses of policy-relevant topics carried out by the European institutions rather than abstract situations. This more realistic approach and sample substantially benefit the external validity of the inferences derived in this type of experiment (Grimmelikhuijsen et al. 2017). However, public officials may not exercise their discretion in a hypothetical policy scenario in the same way that they would during actual policy preparations. Any generalizations from our hypothetical policy context to real-world behaviour thus require further validation on actual decision-making (see Andersen and Jakobsen 2017). Unfortunately, the time-frames involved in political decision-making may make it very difficult to verify the identified mechanisms in the real world. Furthermore, any attempt at generalizing our findings to other public officials in the European Parliament (who often have different roles) or to MEPs and other political actors, would naturally require further substantiation among these sets of actors. We particularly consider the extension of our analysis to MEPs (and specifically to rapporteurs) a very interesting avenue for future research.

Another current limitation of our analysis is—although our research design incorporates different policy scenarios—the limited number of observations which does not allow us to explore potential sources of heterogeneity in the observed effects across distinct policies. Yet, the content of the scenario might matter. One might indeed hypothesize that individuals are prompted to adopt a ‘prevention focus’ particularly when the decision under consideration has tangible rather than intangible effects, or when the policy issue has higher salience (within the European Parliament or the broader public). These potential conditioning effects of issue salience and tangibility constitute important avenues for further research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to all survey respondents for their time and participation. We also wish to thank the editor, three anonymous referees, Nadine van Engen, Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen, Michel Handgraaf, Amie Kreppel and the participants at the following conferences for constructive and helpful comments on earlier versions of this article: the Annual Work Conference of the Netherlands Institute of Government (Nijmegen, November 2015), the 8th Pan-European Conference on the European Union (Trento, June 2016), and the SABE/IAREP Conference on Behavioral Insights in Research and Policy Making (Wageningen, July 2016). Colin R. Kuehnhanss (PhD Fellowship) and Benny Geys (grant nr. G.0022.12) are grateful to the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) for financial support.

APPENDIX A

SOURCES FOR THE POLICY SCENARIOS

European Commission. (2013). EU measures to tackle youth unemployment. Brochure, available from: http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=11578&langId=en.

European Commission. (2013). European Commission guidance for the design of renewables support schemes. Commission Staff Working Document, available from: http://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/com_2013_public_intervention_swd04_en.pdf.

European Parliament. (2010). The promotion of cycling. Note, available from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2010/431592/IPOL-TRAN_NT(2010)431592_EN.pdf.

European Parliament. (2013). Endangered languages and linguistic diversity in the European Union. Note, available from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2013/495851/IPOL-CULT_NT(2013)495851_EN.pdf.

European Parliament. (2013). Regional strategies for industrial areas. Note, available from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/regi/dv/pe495848_/pe495848_en.pdf.

APPENDIX B

GRAPHICAL PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

Notes: The figure presents results obtained from logistic regression models with standard errors clustered at the level of the individual respondent. Panel I presents the overall effect of organizational identification, while Panel II displays separate effects depending on the selection frame provided to respondents. In both cases, the graphical representation on the left-hand side is based on the regression results for EU_Power (average across the 13 autonomy questions) to operationalize organizational identification, while the graphical representation on the right-hand side is based on the regression results for EU_Concerns (EU concerns – Home concerns questions).