Measurement and evaluation of community engagement in complex, chronic medical conditions: HIV and obesity as exemplar conditions

Summary

Objective To systematically review, describe, and compare quantitative measures of community engagement in obesity and HIV prevention research. Materials & Methods A systematic review adhering to PRISMA and PROSPERO guidelines was conducted, searching seven databases. Screening and quality assessment were carried out by four reviewers independently. Studies were included if they explicitly used community engagement for obesity or HIV prevention and quantitatively measured community engagement. Extracted data included descriptions of community engagement, measurement constructs, and statistical results. Results Of 8922 studies screened by title and abstract and 1326 studies screened by full text, 13 studies were included from obesity prevention and 42 studies from HIV prevention. The studies used a range of terms for community engagement, highlighting differing approaches and challenges in measurement. Quantitative measures of community engagement varied across the studies. When change over time in community engagement was analyzed, an increase in engagement was generally found, and when an association between engagement and health was tested, a positive association was generally found. Conclusion Despite diverse measurement approaches, drawing parallels between obesity and HIV prevention offers new pathways to strengthen community engagement evaluations through the iteration of existing measures across the two fields.

Abbreviations

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- SCOPE

-

- Sustainable Childhood Obesity Prevention through Community Engagement

-

- YEAH!

-

- Youth Engagement and Action for Health

-

- RCTs

-

- randomized control trials

1 INTRODUCTION

Community engagement plays an important role in enhancing disease prevention, public health, community initiatives, and other outcomes.1-5 Within public health literature, obesity stands out as a condition that requires community engagement for effective prevention and is a major focus of community engagement research.6-11 Obesity prevention studies typically select community engagement tools from those used in other obesity studies. Examination of tools used in other fields of research may broaden the available insights and directions for research on community engagement in obesity prevention, and finding tools that can be translated into obesity may indicate tools that translate more broadly. Given numerous studies on community engagement across the breadth of public health issues,1-5, 12-14 a pragmatic starting point must be determined. A comprehensive review3 of 319 studies that used community engagement to address inequalities found HIV to have the most studies included (n = 51) followed by cancer screening (n = 41). Community engagement research in HIV prevention emerged in the 80s,15 and others suggest lessons learned about community engagement in HIV prevention may be relevant to other fields. For example, Brown, O'Donnell, Crooks and Lake16 argue engaging the community in HIV prevention had, and continues to have, a positive impact on HIV outcomes, and that these impacts may be translatable to other topic areas within health promotion.

As public health concerns, HIV and obesity share important characteristics. Both are described as complex, chronic conditions, with multiple interacting causal factors, ranging from individual behaviors to societal policy settings, operating both above and below the skin, indicating the need for multilevel, complex solutions.7, 17-19 While HIV first emerged as an acute condition that quickly and tragically took the lives of many people, advancements in both treatment and prevention mean HIV has become a chronic condition, presenting some of the same challenges as obesity, where long term, chronic side effects from HIV and its treatment require maintenance.20 In the cases of both obesity and HIV prevention, co-creation of responses that engage key actors at the different levels of cause and effect (behaviors, environments, policies) are needed to create a comprehensive response.7, 16, 19

There is substantial quantitative and qualitative literature evaluating and providing guidance on community engagement in the fields of HIV and obesity broadly, including community-engaged research, community engagement in health services, and peer-led services. The range of evidence focused on prevention is narrower. It appears some community engagement methods in prevention are better than others, but determining which approaches are most effective remains difficult.1, 3, 5 While qualitative syntheses have provided recommendations for how to engage communities and possible factors to consider for measurement, how to measure these qualitative constructs (e.g. individual skills, relationships between communities and organizations, or improved initiatives by tailoring to communities) remains a gap in knowledge limiting the ability for tool development and measurement comparisons.12-14 Making the roles various mechanisms play and the relationships between them clearer will improve the effectiveness of disease prevention. A crucial next step involves systematically identifying how community engagement has been quantified to allow a more rigorous comparison of the effectiveness of different approaches and the ability to create formal theories of which mechanisms in combination may produce better outcomes.3

Quantifying community engagement in prevention would provide opportunities for standardized definitions and measures.12, 13 Several authors describe community engagement as an umbrella term capturing a spectrum including concepts like informing, involving, mobilizing, and empowering, which are sometimes organized by differing levels of depth of community engagement.4 Examples of this variation in descriptions of community engagement range from involving community in developing health actions; to training community members to lead and deliver health actions; to empowering communities to take their own defined actions to improve health outcomes.3, 13 Deeper levels of engagement along this spectrum (i.e., closer to empowering than informing) have been reported as leading to better health outcomes, but are difficult to measure.4

- local relevance and determinants of health

- acknowledging the community

- disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners

- seek and use the input of community partners

- involve a cyclical and iterative process in pursuit of objectives

- foster co-learning, capacity building, and co-benefit for all partners

- build on strengths and resources within the community

- facilitate collaborative, equitable partnerships

- integrate and achieve a balance of all partners

- involve all partners in the dissemination process

- plan for a long-term process and commitments.

How is community engagement measured in the HIV and obesity prevention literature?

What are the similarities and differences in measurement of community engagement between HIV and obesity prevention research?

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.24 The review was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021258083; May 30, 2021).

2.1 Search strategy

Searches were conducted in Embase, Medline, Informit Health Collection, Global Health, Cochrane Library, SocINDEX, and Psycinfo. The search strategy was formulated by ADB, SA, and CB with input from a research librarian. Additionally, search terms from other reviews of community engagement informed the search terms.4, 8, 25, 26 Key concepts and search terms are documented in Table S1. The original search was run on June 27, 2021. A hand search of reference lists from included studies was also undertaken.

2.2 Study selection

The review targeted quantitative studies of initiatives designed to prevent obesity or HIV that explicitly use community engagement, based on the definition provided by the WHO23 as a component of the initiative. To be included, studies had to be peer-reviewed original research published after 1981 and written in English. Studies were included if they presented quantitative measures of community engagement in prevention. Studies were not included if the only quantitative measure of community engagement was a numeric rating assigned to qualitative data if the study provided quantitative data related to the health outcome of interest but not about community engagement specifically, if the study referred to treatment, or if it only provided quantitative data on an individual's engagement in their own health, as opposed to promoting the health of others.

Duplicates were removed using a combination of the Systematic Review Accelerator,27 Endnote, a method designed by Bramer, Giustini, de Jonge, Holland and Bekhuis,28 Covidence,29 and manual screening. Covidence was used to facilitate study screening. After the initial screening of abstracts, all articles at the full-text review stage were independently reviewed by two reviewers (ADB, JH, TF, PF). One author (ADB) screened all articles at the full-text phase, and three others served as second reviewers (JH, TF, PF). Reviewers worked independently and discussed discrepancies, closely considering the original criteria to reach a final decision, with input from a third reviewer in the case of unresolved discrepancies.

2.3 Data extraction

ADB, SA, CB, JH, and TF collaboratively developed a data extraction schema, which included authors, year of publication, study title, country, project name, project objective, whether it was about HIV or obesity prevention, term or phrase used for community engagement, description of community members carrying out community engagement, study design, type of tool used to collect community engagement data, number of participants, community engagement measurement construct, measured enablers or barriers to community engagement, whether an increase in community engagement over time was reported, and whether there was an association between community engagement and the health behavior or outcome of interest. The term used for community engagement was identified by searching each article for words that (1) aligned with the WHO definition and (2) were connected by the authors of the paper to the quantitative construct measuring community engagement. ADB extracted data from all studies, with TF or JH cross-checking 20% of the studies for accuracy.

2.4 Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute's critical appraisal tools were used to assess study quality, based on the study type.30 The checklist gives each study a rating of yes, no, unclear, or not applicable for between 8 and 12 items (depending on the study design). Each study was given a numeric rating based on the number of ‘yes’ ratings given. Quality assessment was not used to eliminate studies from the review. ADB assessed all studies, with TF or JH cross-checking 20%.

2.5 Data synthesis

To synthesize the results, data were coded based on the attributes listed above to identify patterns in how community engagement in HIV and obesity prevention was measured. The papers were then grouped by the tool they used for measurement. The tools were coded to the 11 community engagement principles developed by Goodman, Sanders Thompson, Johnson, Gennarelli, Drake, Bajwa, Witherspoon and Bowen21 to identify similarities and differences between measurement tools and patterns between measures chosen and effectiveness. Tools to measure community engagement were additionally classified into two categories: internal and external, reflecting two major trends in the measures that emerged from the analysis. Internal measures primarily gauged the intrinsic attributes and perspectives of individuals, such as their knowledge, attitudes, or self-perceived skills related to community engagement. In contrast, external measures evaluated tangible actions or changes in the broader community environment, capturing the observable outcomes that arise due to the collective efforts of community members in health initiatives.

3 RESULTS

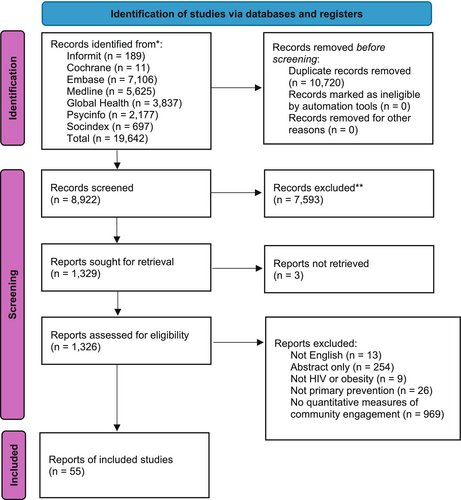

The initial search returned 19,642 records. Duplicates were removed manually from the results returned by Informit, removing 124 records. The Systematic Review Accelerator deduplicator tool was used to remove 9486 records.27 Endnote's deduplication tool removed 467 records. A further 696 records were removed in Endnote using the methods described by Bramer, Giustini, de Jonge, Holland and Bekhuis.28 Finally, when the records were imported to Covidence,29 a further 6 records were removed, resulting in 8922 studies for screening. Of the 1329 papers that were identified from the abstract as potentially containing a quantitative measure of community engagement, 969 studies did not contain such a measure, despite meeting other study criteria. Fifty-five studies were identified for data extraction and synthesis (Figure 1).

3.1 Description of included studies

The 55 selected studies demonstrated various characteristics of community engagement measurements in HIV and obesity prevention. Table S2 displays the basic characteristics of these studies, which are organized by outcome (HIV or obesity), then by study design, and finally by year. Most HIV studies were conducted in the US (n = 15),31-45 several countries across Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 11),46-56 or India (n = 10).57-66 The remaining studies (n = 6) were spread across the Americas, Asia, and Europe.67-72 The US similarly had the most studies measuring community engagement in obesity prevention (n = 7),73-79 but in contrast with HIV, the remaining studies were conducted in Canada (n = 3),80-82 Australia (n = 1),83 Italy (n = 1),84 and one paper comparing two studies in the US and Australia.85 Examples of community engagement measures in HIV existed across all continents except Oceania and represented a wide range of types of countries, whereas in obesity prevention, these measures were only documented in high-income countries.

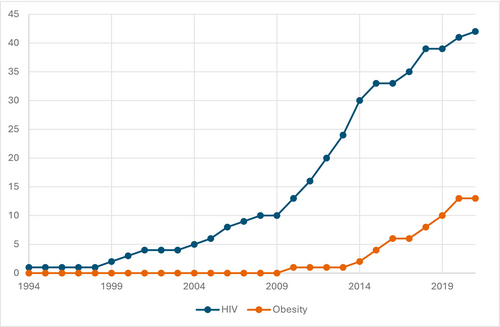

Publications in the HIV prevention literature started earlier (in 1994)35 than in obesity prevention (in 2010).77 Recently, the number of studies in both areas appear to have increased at a similar rate, though rapid growth in HIV studies started earlier (2010)39, 49, 50 than in obesity (2014)78 (Figure 2). In HIV studies, 9 of the 10 studies conducted in India were part of Avahan, an initiative launched by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation in 2003 to combat HIV in India, distinguished by a focus on community engagement, being data-driven, and operating at scale.57-65 In obesity prevention, there were more examples of projects with multiple publications: Sustainable Childhood Obesity Prevention through Community Engagement (SCOPE) (n = 3),80-82 Youth Engagement and Action for Health (YEAH!) (n = 3),74, 78, 79 Romp and Chomp (n = 2),83, 85 and Shape Up Somerville (n = 2).75, 85 Uniquely, one of the publications used the same measurement questionnaire across two different countries, Romp and Chomp and Shape Up Somerville, to further refine and develop the use of the questionnaire.85

3.2 Definitions of target populations and community engagement

With respect to target populations for community engagement, both the HIV and obesity prevention described community members who were carrying out engagement as (1) professionals who work directly with grassroots community (n = 8; n = 5, respectively),31, 39-41, 49, 69, 71-73, 76, 80, 83, 85; (2) residents of a geographic area (n = 3; n = 4),33, 48, 54, 75, 77, 81, 82 or (3) young people (n = 7; n = 4).34, 36, 44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 74, 78, 79, 84 HIV had several additional descriptions related to populations considered at risk, specifically sex workers (n = 11)47, 57-65, 67 and men who have sex with men (n = 6).44, 45, 47, 65, 66, 70 In other studies in HIV prevention, community was defined based on social identities, particularly race or gender (n = 15).31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 42, 44, 45, 50, 51, 55, 56, 68, 86 The terms used to describe community engagement in both areas varied considerably, with engagement being the only overlapping term.

3.3 Study design and measurement characteristics

The majority of HIV and obesity studies relied on self-report surveys or interviews to measure community engagement (e.g. participants' level of agreement that their community would come together in the face of a problem affecting their community) (n = 30 and n = 7, respectively).32-40, 46, 48, 50-52, 55-60, 62-65, 67-70, 72-76, 79, 84-86 However, there were examples of other ways to measure community engagement, such as observation (n = 4 and n = 5),47, 49, 54, 61, 78, 80-83 and among the HIV studies, network data (n = 2)44, 66 and group consensus (n = 1).71 A small number of studies combined multiple methods to measure community engagement (n = 5 and n = 1).31, 41, 42, 45, 53, 77 About half of the studies were cross-sectional, and that approximate ratio has persisted since community engagement research in HIV prevention started (Table S1). Since 2010, there has been a steady increase in the number of randomized control trials (RCTs) incorporating measures of community engagement (Table S1). The HIV literature showcased a range of participant sample sizes when measuring community engagement from 1 to 100 participants (n = 13)31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 49, 54, 66, 68, 69, 71, 72, 86 to over 2000 participants (n = 5).34, 51, 57, 60, 65 Most of the obesity studies were smaller (1–100 participants, n = 6),73, 75, 77, 79, 83, 85 though there were examples of 101–500 (n = 3)74, 78, 84 and 501–1000 (n = 1).76

The results across the studies support the positive association between community engagement in prevention and health outcomes (Table 1). Of the 22 studies in HIV prevention that statistically tested an association between community engagement and improvement in HIV outcomes or behaviors, 19 studies found a positive association34, 38, 42, 44, 47, 48, 51, 55, 57, 58, 60-62, 64, 65, 67, 69, 70, 86 and all four of the obesity prevention studies that carried out a similar analysis found a positive association (Table 2).74, 79, 83, 84 Thirteen of the fifteen studies that measured community engagement in HIV prevention at multiple time points found an increase in community engagement over time33-35, 38, 44, 45, 47, 49, 52, 61, 68, 71, 86 and six of the seven obesity prevention studies also found an increase (Table 3).74, 79-83

| Authors | HIV or obesity | Project names | Community engagement measurement constructs | Increase in community engagement over time? | Association between community engagement and health behavior or outcome? | Internal or external measure of community engagement | Focus on local relevance and social determinants of health | Acknowledge the community | Disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners | Seek and use the input of community partners | Involve a cyclical and iterative process in pursuit of objectives | Foster co-learning, capacity building, and co-benefit for all partners | Build on strengths and resources within the community | Facilitate collaborative, equitable partners | Integrate and achieve a balance of all partners | Involve all partners in the dissemination process | Plan for a long-term process and commitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharjee et al | HIV | N/A | regular outreach contacts; key populations: peer educators ratio | Yes | Yes | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Blanchard et al; Kuhlmann et al; Nagarajan et al; Saggurti et al; Gaikwad et al; Parimi et al; Beattie et al; Gurnani et al; Chakravarthy et al; Kerrigan et al | HIV | Avahan (Including Aastha; Karnataka Health Promotion Trust; the Swagati project); Programa Integrado de Marginalidade (PIM) | power within; power with; power over; average percentage of volunteer FSWs participating on seven program-related committees, as compared to the total committee membership; claiming identity as a sex worker; individual agency to refuse clients when tired and to make decisions about one's own life; self-efficacy for condom use with clients; self-efficacy for service utilization; self-confidence in obtaining condoms and in giving advice; mental health; collective identity of attending events where one could be identified as a FSW; collective efficacy for FSWs working together to solve problems and for FSWs working together to achieve goals; collective agency for standing up for those in need; collective action of FSWs working together to demand entitlements; social cohesion among FSWs in the cluster; collective identity; collective agency; participation in collective spaces; collective ownership; vulnerability and violence faced by FSWs in their sex work settings; collective efficacy; collective action; participation in public events; collectivisation; collective power; exposure to CM activities; number of FSWs becoming members of sex worker organizations (community-based organizations, self-help groups and community committees) or members of local HIV program committees; project sites; drop-in centres; STI clinics; regular contact with the program (i.e. contacted at least once in a year); proportion of the total estimated female sex worker population reached each month; number of peer educators; female sex workers contacted by peer-educators; perceived social cohesion and mutual aid among sex workers from same area; participation in secondary associations | Yes | Yes | both | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Darrow et al | HIV | Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation (PRECEDE)/Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development (PROCEED) model | acted to solve AIDS problem | Yes | Yes | external | X | ||||||||||

| Romero et al | HIV | Woman to Woman: Coming Together for Positive Change | collective efficacy; sense of community; perceived control at the organizational level; perceived control at the community level; sexual communication; power in relationships | Yes | Yes | Internal | X | X | |||||||||

| Wilson et al | HIV | Barbershop Talk with Brothers | community empowerment | Yes | Yes | internal | X | ||||||||||

| Young et al; Young et al; Walsh et al; Mulawa et al; Schneider et al | HIV | Harnessing Online Peer Education (HOPE); PreP Chicago; Vijana Vijiweni II; 2 unnamed projects | degree centrality; network ties; participating in group discussions; using social networks to discuss sexual behaviors; total number of network contacts that are PrEP users; Facebook friend degree; Facebook friendship ties among control participants at each time point; successful recruitment; booster completion; being aware of PrEP; using PrEP; leadership; innovativeness; eigenvector centrality; network brokerage; confidence; conversations about HIV/GBV; in-degree centrality and betweenness centrality; whether participants encourage condom use among their peers; a new measure of bridging within global networks using a link deletion approach; bridging potential | Yes | Yes | both | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Lippman et al | HIV | HPTN 068 | community mobilization measure: shared concern: HIV; critical consciousness; leadership; organization & networks; collective activities; social cohesion; social control | No | Yes | internal | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Crittenden et al | HIV | N/A | self-efficacy for community prevention (can talk about HIV prevention); community HIV prevention index (# of 6 activities reported for last 2 months: led discussion/talked prevention/safer sex with: partner/other adults/own children/other young people/contributed money or time); diffusion effect | N/A | Yes | both | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Haw et al | HIV | Needle and syringe exchange program implemented by the Yundi Harm Reduction Network (YDHR) | methods of outreach carried out; level of ease in exchanging needles; perceived level of acceptance by IDUs; perceived level of confidentiality IDUs provide with regard to drug habits and HIV status; able to easily access IDU clients; trusted by IDU clients; familiar with situation of IDU clients; cost-effective service delivery option; salaries; monitoring IDUs; support from family; workload; fear of relapse | N/A | Yes | both | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Li et al | HIV | Community Champions HIV/AIDS Advocates Mobilization Project (CHAMP) | a community engagement scale based on the literature | N/A | Yes | external | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Starmann et al | HIV | SASA! | material exposure (posters, comics, picture cards, information sheets); mid media exposure (dramas, audio plays); interpersonal communication (discussion activities with change agent, seeking change agent support, discussion about SASA! with social network members); multi-channel exposure (having material and mid media/activity exposure) | N/A | Yes | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Fritz et al | HIV | The Sahwira HIV Prevention Program | several mediating variables related to friends interacting with their friends around HIV risk | N/A | No | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Shumba et al | HIV | AIDS Relief Uganda | community mobilization metric based on a site capacity assessment tool | N/A | No | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Carlson et al | HIV | The Young Citizens Program | child collective efficacy; deliberative efficacy; communicative efficacy; academic efficacy; emotional control; peer resistance | Yes | N/A | internal | X | X | |||||||||

| Cornelius et al | HIV | State of Maryland HIV Prevention Community Planning Group | meeting atmosphere; everyone participates in discussions; no fighting for status; no fighting for hidden agendas; group adjusts to changing needs, situations; members feel safe in speaking out; meetings have free discussions; reports are routinely made to group; minutes accurately reflect meeting; meeting times work well with schedule; location of meetings is convenient; presentations are clear, concise | Yes | N/A | external | X | ||||||||||

| Freudenberg et al | HIV | Women's Drop-In Center | how many times in the last week last week participants carried out various HIV/AIDS prevention tasks | Yes | N/A | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Kasmel et al | HIV | Drug Abuse and AIDS Prevention program | activation of the community; competence of the community in solving its own problems; porgram management skills; creating a supportive environment | Yes | N/A | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Li et al | HIV | N/A | HIV championship readiness; psychological flexibility conceptualized as an individual's ability to persist in value-driven behavior in the face of negative emotions or feelings; mindfulness, defined as the capacity to adopt a non-judgmental stance and attend to the present moment; the perceived value in 10 different areas of life (e.g., work, family, friends, etc); the consistency of one's actions with regards to their own values in each of these areas | Yes | N/A | both | X | ||||||||||

| McCreary et al | HIV | Mzake ndi Mzake (Friend-to-Friend) | peer leaders' session management; peer leaders' interpersonal facilitation; Session rating of ‘class versus peer group’; crowding; adequacy of lighting; uncomfortably hot or cold conditions; adequate privacy to discuss sensitive topics | Yes | N/A | external | X | ||||||||||

| Brown et al; Smith et al; Tyrell et al | HIV | New York State Faith Communities Project; 2 unnamed projects | church provides venue for teaching adolescents about sexual behavior; uncomfortable with the topic; unsure about how to teach the topic; did not think the subject should be taught to adolescents; thought discussion of sex may encourage adolescents to become sexually active; if general health promotion programs and/or specific HIV prevention programs were offered in their respective churches; percenage of events defined as “spiritual”, “HIV/AIDS-related”, “technical assistance/capacity building”, “needs assessment/planning”, and “forum”; do you provide/facilitate HIV/AIDS education to the community?; perceived need for HIV/AIDS-related education/prevention services; how prepared are you to provide HIV/AIDS education/prevention information?; would you be willing to meet with community-based HIV/AIDS education/prevention providers?; lack of financial resources to run prevention programs; lack of qualified staff to conduct prevention activities; HIV/AIDS is not part of our mission or primary service activities provided by this organization; the clergy/spiritual leaders do not have the experience or ability to provide HIV/AIDS prevention/education; opposition to homosexuality/bisexuality; lack of knowledge/information about HIV/AIDS; opposition to condom use; opposition to drugs and alcohol; HIV/AIDS is not considered a serious problem in the community we serve; fear of HIV/AIDS; the religious community opposes the implementation of HIV/AIDS prevention activities; negative attitudes toward people who are at risk for HIV or may be HIV infected; the clergy/spiritual leaders oppose the implementation of HIV/AIDS prevention activities; the outside community opposes the implementation of HIV/AIDS prevention activities | N/A | N/A | both | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Chowdhury et al; Li et al | HIV | Collaborative HIV Prevention and Adolescent Mental Health Project (CHAMPions) | number of adolescents the program was delivered to; the individual's intention or decision to participate; knowledge and skills for participation; the salience of participation for the individual; the habitual and automatic processes fostered by the individual for participation; attitude toward participating in HIV prevention; social norms related to participation; expectations about the benefits of participating in HIV prevention; self-concept in relation to participation in HIV prevention; self-efficacy in relation to the same; perceived environmental constraints to participation | N/A | N/A | both | X | X | |||||||||

| Hargreaves et al | HIV | Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE) | acceptability of community mobilization; I was active in trying to formulate and do an ‘action plan’ with my center; I participated in the activities organized by my center in our village and local area; I think my center was successful in trying to change things in our village through its action plans | N/A | N/A | Internal | X | X | |||||||||

| Reed et al | HIV | Connect to Protect (C2P) | objectives coded as completed, abandoned, or still in progress; proportion of objectives completed; coalition members listed as youth on key actor logs | N/A | N/A | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Reeder et al | HIV | Red Cross prevention training | number of informal conversations and discussions and number of formal educational activities; community; understanding; personal development; esteem; values; knowing a PWA; barriers | N/A | N/A | both | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Rovniak et al | HIV | Business Environments Against the Transmission of AIDS (BEAT AIDS) | willingness to distribute condoms/brochures; I would like to have my participation in this program publicized in a positive way in print, TV, and radio media; I would be willing to put a decal in the window of my business showing I am participating in the BEAT AIDS program; I would be interested in meeting with other Hillcrest business owners several times a year to discuss ways to prevent AIDS in this community; I would be willing to sign a letter recommending that other Hillcrest businesses participate in the BEAT AIDS program; I would be willing to sign a letter addressed to a member of Congress asking for tax breaks for businesses that hand out condoms or AIDS prevention brochures.; overall, I thought my experience in the BEAT AIDS program was …”; the BEAT AIDS program did not take a lot of time or effort; made me feel I was making a positive contribution to the community; helped attract new customers; helped me keep existing customers; resulted in positive comments from customers; resulted in positive comments from employees | N/A | N/A | internal | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Wagemakers et al | HIV | Public Health Service (PHS) of Amsterdam's STI/HIV prevention programme | rating based on Pretty's typology derived from a Coordinated Action Checklist; the STI/HIV program is an asset (to sexual health promotion); to attain the goals of the STI/HIV program, the right partners are involved; equity of the partners is essential for good collaboration; the contribution of the different partners is to everyone's full satisfaction; I have a special interest in participating in the STI/HIV program because of my position or organization; I am able to contribute to the STI/HIV program in a satisfactory way (time, means, etc.); I feel involved in the STI/HIV program; I can contribute constructively to the STI/HIV program because of my expertise; there is agreement on the mission, the goal and the planning within the STI/HIV program; the STI/HIV program achieves regular (small) successes; the STI/HIV program functions well (working structure); the STI/HIV program partners communicate in an open manner; the STI/HIV program partners work together in a constructive manner and know how to involve each other when action is needed; the STI/HIV program partners are willing to compromise; in the STI/HIV program conflicts are dealt with in a constructive way; the STI/HIV program partners will carry out decisions and actions loyally; I create goodwill and involvement for the STI/HIV program within my organization; the STI/HIV program is willing to recruit new partners in the course of time | N/A | N/A | both | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Botchwey et al; Linton et al; Millstein et al | obesity | Youth Engagement and Action for Health (YEAH!) | group resiliency; group cohesion; roles and participation; group members shared beliefs; group belief in positive outcome; opportunities for control in group work; coordinator/leader characteristics; self-efficacy for health and advocacy behaviors; active participation; optimism for change; peer support for healthy behaviors; group resiliency; advocacy outcome efficacy; assertiveness; participatory competence and decision making; pride in group work; group outcome efficacy; health advocacy history; assessment conducted; engagement process; decision makers engaged; level/history of advocacy actions; pride in group work; roles and participation; benefits from participating; intent to remain involved; opportunities for control; opportunities for involvement; collective efficacy; group outcome efficacy; group cohesion; group advocacy; follow-up group resiliency; coordinator characteristics; personal advocacy activities since starting YEAH!; self-efficacy for health and advocacy behaviors; active participation in advocacy; optimism for change; openness to healthy behaviors; advocacy outcome efficacy; group resiliency; assertiveness; health advocacy history; participatory competence and decision making; knowledge of resources; social support for health behaviors; self-efficacy for health and advocacy behaviors; active participation; assertiveness; health advocacy history; knowledge of resources; social support for health behaviors | Yes | Yes | both | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Kasman et al; Korn et al | obesity | Romp & Chomp; Shape Up Somerville; Shape Up Under 5 | engagement; number of undirected ties an individual agent has with others in the community; Within-group assortativity characterizes the propensity of individual agents to be socially connected with other members of their community group; knowledge is a vector of five independent, continuous variables describing the direction and accuracy of information an individual agent possesses about a pertinent aspect of children's health in the community; exchange of skills and understanding; willingness to compromise and adapt; ability or capacity to have an effect on course of events, others' thinking, and behavior; action of directing and being responsible for a group of people or course of events; belief and confidence in others | Yes | Yes | internal | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| De Rosis et al | obesity | beFood | had a great influence on their peers; adults gave them trust; felt they played a leading role; level of responsibility in the project; evaluation of assigned roles and responsibilities despite or because they were very challenging in their opinion; felt proud of their participation in the beFood experience; evaluation of beFood as a health promotion intervention; would recommend beFood as a training and developmental project of ‘Alternanza Scuola-Lavoro.’ | N/A | Yes | internal | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Amed et al; Amed et al; Kennedy et al | obesity | Sustainable Childhood Obesity Prevention through Community Engagement (SCOPE) | resulted in at least one identified action item; community engagement meetings results in a plan to follow up; meeting focused on planning or action; actions by community partners; active partnerships; participation; leadership; community structures; role of external supports; asking why; obtaining resources; skills, knowledge, learning; links with others; sense of community | Yes | N/A | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Berman et al | obesity | Healthy Lifestyles Initiative | policy, systems, and environmental activities implemented; attended at least 1 Healthy Lifestyles Initiative training session; completed a Healthy Lifestyles Initiative action plan; participated in a community coalition supported by the Healthy Lifestyles Initiative; received one-on-one support from a Healthy Lifestyles Initiative staff member; received materials and resources from a Healthy Lifestyles Initiative staff member; number of and types of materials they used; how frequently they used the materials | N/A | N/A | external | X | ||||||||||

| Kemner et al | obesity | Healthy Kids, Healthy Communities | leadership; partnership structure; relationship with partners; partner capacity; political influence of partnership; perceptions of the partnership's involvement with the community and community members | N/A | N/A | external | X | X | |||||||||

| Kim et al | obesity | Pioneering Healthier Communities | likelihood of neighborhood residents taking action in response to a local public health issue; presence of an organized neighborhood association or group that has the ability to influence healthy living; occurrence of action by the neighborhood in the past 12 months to improve health outcomes or public safety that was of concern to people in the neighborhood service department being threatened with budget cuts | N/A | N/A | external | X | X |

| HIV | Obesity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Yes | No | N/A | Total | Yes | No | N/A | Total |

| Internal measure of community engagement | 7 | 0 | 8 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| External measure of community engagement | 8 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Focus on local relevance and social determinants of health | 3 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Acknowledge the community | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seek and use the input of community partners | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Involve a cyclical and iterative process in pursuit of objectives | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Foster co-learning, capacity building, and co-benefit for all partners | 7 | 1 | 11 | 19 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Build on strengths and resources within the community | 10 | 2 | 6 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Facilitate collaborative, equitable partners | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Integrate and achieve a balance of all partners | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Involve all partners in the dissemination process | 8 | 1 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Plan for a long-term process and commitment | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| HIV | Obesity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Yes | No | N/A | Total | Yes | No | N/A | Total |

| Internal measure of community engagement | 6 | 1 | 8 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| External measure of community engagement | 9 | 0 | 11 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Focus on local relevance and social determinants of health | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Acknowledge the community | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seek and use the input of community partners | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Involve a cyclical and iterative process in pursuit of objectives | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Foster co-learning, capacity building, and co-benefit for all partners | 8 | 1 | 10 | 19 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Build on strengths and resources within the community | 7 | 1 | 10 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Facilitate collaborative, equitable partners | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Integrate and achieve a balance of all partners | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Involve all partners in the dissemination process | 4 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Plan for a long-term process and commitment | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Tables 2 and 3 also display the results of the synthesis of the measurement tools. Both HIV and obesity had a mix of tools that used internal and external methods, along with examples that used multiple measures that made use of both. Coding the tools to the community engagement principles yielded insights into where community engagement in HIV and obesity prevention is focused, with similar patterns emerging across both fields. ‘Foster co-learning, capacity building, and co-benefit for all partners’ and ‘Build on strengths and resources with the community’ were the most common principles measured, and significant gaps emerged in measuring ‘Disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners’, ‘Involve a cyclical and iterative process in pursuit of objectives’, and ‘Plan for a long-term process and commitment.’ Notably, HIV had at least one tool for each of the principles, providing potential for translation into obesity prevention.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Statement of principal findings

This systematic review summarized the published literature of quantitative measures for community engagement in the contexts of obesity prevention and HIV prevention. However, coding the measures into community engagement principles21 revealed patterns in what is measured in both fields and where there may be gaps. For HIV and obesity prevention research, most measures were self-reported on a single occasion, but there were some examples of observation methods used over multiple time points, particularly in HIV prevention where RCTs were increasingly being used to evaluate effectiveness. When statistical methods were used to measure changes in engagement over time or associations between community engagement and health behaviors or outcomes, community engagement was generally found to increase and be associated with health outcomes or behaviors of interest.

Given that only a small number of studies reported no significant association with health outcomes or no increases in community engagement, there is insufficient data to determine whether certain community engagement principles are more effective than others. This may be partly due to positive-outcome bias in peer review,87 where studies with positive findings are more likely to be published than those with null or negative results. Many of the community engagement studies we reviewed did not report on health outcomes or failed to analyze the relationship between community engagement and specific outcomes. As in other fields, it is crucial that future research publishes studies where community engagement had no effect or even adverse effects, to improve our understanding of effective approaches. One way to address this is by responding to the call for the use of multiple measures of community engagement. Although many studies employed measures that reflected multiple community engagement principles, they did not conduct analyses that differentiated between them. If future studies use multiple measures and test each against relevant health outcomes, more nuanced insights into which components of community engagement are effective—and which are not—could emerge.

Previous reviews in obesity prevention have identified community engagement as critical to obesity prevention initiatives but have not reported on actual measurement of community engagement.6-11 This has created tension where there is growing acknowledgment of the importance of community engagement but in many cases, insufficient data to study a link between community engagement and health outcomes such as obesity prevalence.88 Our review affirms the importance of community engagement and highlights the gap in measurement, with only 13 studies across eight projects quantitatively measuring community engagement in obesity prevention since 2014. It also identifies candidate measures of community engagement from recent studies that have used rigorous designs and quantitative measures of community engagement,80-82 complex modeling,83 and internal and external measures of community engagement.74 These measures have been classified based on an existing framework to reveal areas where there are existing measures to build on and gaps that need to be addressed.

A similar tension has been observed in the broader field of public health.1-5, 12-14 A large review carried out by Popay, Attree, Hornby, Milton, Whitehead, French, Kowarzik, Simpson and Povall1 in 2007 noted that study designs (e.g. cross-sectional) at that time did not allow for attributing causality to community engagement in health outcomes. Further, while RCTs are a stronger design for studying causality, Rifkin12 highlights the drawbacks of RCTs in understanding community engagement because of the wide definitions of “community” and “participation,” creating context-specific results that are difficult to generalize, calling instead for community engagement to be viewed as a process, involving multiple measures. O'Mara-Eves, Brunton, Oliver, Kavanagh, Jamal and Thomas5 echo this call for studies that use multiple measures that capture the various elements of community engagement over time to evaluate community engagement due to its complexity. Considering measures in relation to the community engagement principles contributes to developing approaches of measuring community engagement with multiple interrelated measures.

Our review has offered some candidate measures and methods in HIV that could be applied to obesity. Since 2011, there have been six randomized control studies in HIV prevention that used community engagement measures at multiple time points.12, 44, 45, 48, 52, 53 The 42 studies within HIV prevention in this review represent a range of constructs to measure community engagement, and 20 of those studies measured community engagement over time. Community engagement principles covered by HIV but not obesity offer strong initial candidates for trial translation. Both HIV and obesity prevention may be able to use these diverse examples from HIV to continue to develop measurement of community engagement in a way that is responsive to ongoing challenges.

4.2 Strengths of the study

Previous systematic reviews of the community engagement literature have either taken a broad quantitative approach seeking an association between community engagement and health outcomes or a qualitative approach, summarizing barriers and enablers to engagement. A strength of this review is that it strikes a middle ground, pulling together details about specific quantitative measures used to evaluate community engagement and pointing to future research to develop community engagement measures. Another strength of this review is the juxtaposition of two distinct health conditions, offering a fresh perspective for future obesity prevention research, especially given the increasing calls to realize the potential of community engagement. The review also adhered to PRISMA and PROSPERO guidelines to ensure rigor.

4.3 Weaknesses and limitations of the study

One limitation is that this review was limited to the published academic literature. Most community engagement work happens at organizational and grassroots community levels and is never intended for, nor makes it to published academic literature. While this means multiple examples are likely to have been overlooked, the intention here is to draw together what can be learned from studies that have proceeded through peer review and identify replicable methods and detailed critique of the pros and cons of the tools applied.

We limited the data corpus to studies published in English and the studies returned were disproportionately from high-income countries, despite the high burden of both HIV and obesity in other parts of the world. Additionally, different countries may have different relative amounts of quantitative and qualitative research focuses, meaning the focus on quantitative measures focuses on research in countries that may favor quantitative research. The findings of this study therefore should not be interpreted to be about community engagement in HIV or obesity prevention in general, but rather specifically focused on quantitative, published measures that could be built on in future work.

Assessing the quality of the studies in this review was challenging. Many quality assessment tools focused on community-based or action research are focused on qualitative research and are challenging to apply to quantitative research. On the other hand, quantitative evaluation tools embrace traditional linear paradigms and focus on health outcomes, as opposed to processes like community engagement, making them not always fit for purpose.

We used a framework based on community-engaged research to synthesize the measures we found rather than one developed for prevention. Using this framework demonstrated how community engagement in other health areas outside of prevention may be relevant to prevention. The focus areas and gaps in the obesity and HIV prevention literature, and the concept of internal and external measures, provide starting points to develop and empirically test a framework that is tailored to prevention.

4.4 Implications and future research

Measures of community engagement in HIV prevention and obesity prevention demonstrated similarities that indicate at least some of the measures in HIV prevention could be trialed in obesity prevention. Both domains have implemented measures in high-income countries, utilized internal and external engagement metrics, and featured similar definitions of community members. Where there are differences, there may be opportunities for the two fields to learn from one another. For example, while obesity emerged as a health issue in high-income countries, it has now spread globally,89 meaning examples from the HIV literature measuring community engagement outside of high-income countries could be relevant in obesity prevention. As the complexity and global scale of obesity are recognized,89 there is a need to consider deepening engagement with a broader range of community members, and the studies in HIV with large sample sizes may offer opportunities to do so in obesity prevention. On the side of HIV research, the importance of structural actions is recognized,90, 91 and obesity prevention research offers quantitative measures of community engagement defined in ways directly relevant to structural actions such as advocacy, partnership, and co-production. The obesity prevention field consistently calls for evaluating complex community-led initiatives.7 HIV literature, with its emphasis on constructs like mobilization or empowerment, could offer valuable insights for these evaluations. This review only considered two health conditions, and future work could apply a similar approach to other health conditions that utilize community engagement to continue to develop a fuller picture of the literature. This review illuminates numerous opportunities to iterate upon existing community engagement measures across health domains, particularly in cases where there already have been multiple uses of the same measure.

Across both health issues, a wide range of constructs were measured to reflect community engagement. While the diversity of terms allows for more specificity in how to define activities that fall under the broad umbrella of community engagement, the definitions of these terms overlap and were not used consistently, creating fragmentation and limiting the ability to build on previous work. In spite of these challenges, HIV and obesity prevention both showcase examples of the multiple studies over time building on and refining measures of community engagement, and the translation of measures across different studies. Both HIV prevention and obesity prevention showcase a diverse range of approaches to capturing internal and external measures of community engagement to capture the range of sites where community engagement may be measured.

5 CONCLUSION

This systematic review found notable diversity in measurement approaches to community engagement in obesity and HIV prevention and a need for consistent quantifiable measures. Drawing parallels between the two fields offered novel avenues for strengthening community engagement evaluations. It is imperative to address the challenges in defining and measuring community engagement, emphasizing its pivotal role in health outcomes and advocating for more cohesive, cross-disciplinary approaches to learning how to best work with communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Penny Fraser's (Deakin University) contribution to this work through assistance with article screening. Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley - Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.