Designing a youth-led Dialogue Forum tool: The CO-CREATE experience

Summary

While obesity prevention represents an established field of research, the inclusion of young people, who are regularly cited as an important priority group, are rarely actioned in long-term studies. This paper focuses on the development of a dialogue tool intended to tackle this issue, engaging, and eliciting insights on the theme of obesity prevention, by young people and for young people. As part of the CO-CREATE project, this tool was co-developed by designers, public health, and youth participation experts, researchers, and young people. Co-creation is a key methodology in the design of the dialogue tool, as young people were involved in all stages of the development process. This paper elaborates on the process of co-designing a dialogue tool that helps explore obesity prevention policy ideas from multiple perspectives, and describes the design principles that informed the process and the final versions of the tool. The purpose of the Dialogue Forum tool is for youth to engage policymakers and other relevant stakeholders to discuss and refine co-created and youth-initiated ideas for healthier food and physical activity environments. We analyze how specific design principles were integrated into different prototypes and the value of this within the project and the field.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past decades, we have seen a large body of published intervention research addressing childhood obesity.1 Systematic reviews of this research conclude that there are beneficial effects of child obesity prevention programs, particularly when targeted to children aged 6–12 years.2, 3 However, when it comes to the older age group of 13–18 years, systematic reviews point to the lack of studies, and conclude that there seems to be a research gap in terms of effective interventions.2, 4-6 “CO-CREATE: Confronting Obesity: Co-creating Policy with Youth”, is a five-year EU-funded project, aiming to reduce the prevalence of obesity among adolescents by working directly with young people to co-create policy solutions that promote healthy food and physical activity environments. The project engaged with adolescents 16–18 years old across five European countries, recognizing this age group's increasing autonomy and, “as they grow to become the next generation of adults, parents, and policymakers, are thus significant agents for change.”7 For the purposes of this paper, we will refer to this target group as “youth”.

An underlying assumption of the CO-CREATE project was that, if youth are involved in co-creating policies that affect them directly, those policies will better reflect their needs. Youth engagement in democratic processes, including in policy development, should be considered as a human right — participating in decisions about them and that affect them directly.1, 8-10 However, youth engagement can take many forms, with tokenism as the lowest degree of participation, to youth-initiated initiatives, which share decision-making with adults, at the high end.11 The current state of youth participation in policymaking processes varies considerably, with select countries facilitating this involvement through youth parliaments, councils, and engagement in other policy implementation processes.12 Many countries have yet to formalize and standardize youth engagement. In 2020, only eight of the 53 countries in the WHO European region reported involving young people in all development stages of a child and adolescent health strategy.13 Increasingly, young people are calling for equal participation opportunities14 and creating impact through independent social movements such as Fridays for Future. In fact, between 2018 and 2022, this movement mobilized 18 million strikers globally to advance action towards the climate change agenda.15

Evidence would suggest that both young people and policymakers stand to gain numerous benefits when youth are involved in policymaking processes.12 Youth involvement is particularly valuable for connecting with and empowering youth16 and for society as a whole to understand young people's perspectives and experiences of the world. It also allows policymakers to develop more informed policies and improve program design and implementation.12 As stated by a participant engaged in the CO-CREATE project, “young people such as myself will live with the results of those policies in the upcoming decades and therefore, it is crucial for us to get a chance to have an impact on our future.”17(p1)

Design methodologies are increasingly utilized in health innovation settings and contributing towards participatory health models,18 as seen at the Mayo Clinic, within the National Health Service and among health research institutions around the world. Within this landscape of encouraging participatory models towards better health outcomes, and to support the CO-CREATE project's policy co-creation process, a multi-stakeholder dialogue tool was developed to connect youth, policymakers, and private sector representatives to discuss and refine obesity prevention policy ideas, and to identify actions that can advance these ideas. This tool is known as the Dialogue Forum.

As part of the research process, interviews revealed that on the occasions that young people meet with relevant stakeholders and discuss themes such as childhood obesity, exchanges could not take the form of actionable outputs because of the uneven dynamics within which they were presented. The development of the Dialogue Forum tool, thus, focused on a two-pronged hypothesis. First, that with an appropriately co-designed tool, youth would be enabled to meet with relevant stakeholders and exchange viewpoints on healthier food and physical activity environments, and secondly, that the tool would facilitate a manner of communication that would be actionable by the parties present. While it is too early to comment on the long-term benefits of a participatory model within a health outcome lens, some initially positive results are outlined in the conclusive chapters of this paper.

Other methods and tools used for stakeholder and youth engagement already exist, such as the World Café19 and appreciative inquiry.20 These tools promote dialogue among participants on a particular topic, and in the case of the appreciative inquiry, the dialogue focuses on creating a shared vision and action plan. We have found that many of these existing tools lack structure and have open-ended dialogues, which can make it difficult to achieve desired goals.19 In other cases, such as with appreciative inquiry, the researchers noted an overemphasis on consensus rather than constructive dialogue, which can limit the appreciation of varied points of view.20 Finally, these tools have not been designed for youth as the main target group, or included youth in the design and development process. With these limitations in mind, we aimed to design a tool that would promote dialogue among a variety of perspectives, give equal space for all voices to be shared and heard, focus on a shared vision and action plan, and be easy to scale, coordinate, and prepare for.

As the Dialogue Forum tool aims to bring together stakeholders with different interests, it is critical to promote a safe, inclusive, and empowering space for all participants, especially youth. This is of particular relevance in the CO-CREATE project, where stakeholders with varying interests, including commercial interests, were invited to discuss an obesity prevention policy and public health initiative. To ensure this, several resources were developed to minimize conflicts of interest and address power imbalances in the Dialogue Forum process.21 In the development and refinement of the Dialogue Forum tool, the measures focused on minimizing power imbalances between youth and adults, safeguarding the policy discussion, and promoting empowerment of youth and securing their rights to participation, in compliance with Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.22

The objective of this paper is to discuss the development process of the CO-CREATE Dialogue Forum tool, the seven principles that informed the design process and the final versions of the tool, and to demonstrate the value of the tool within the scope of our hypotheses. We analyze how these design principles were integrated into different prototypes, and discuss why the involvement of youth throughout the process was crucial. Lastly, we discuss the strengths and limitations of the process, and consider the applicability of the tool beyond the CO-CREATE project.

This paper is part of a CO-CREATE Supplement, a group of articles addressing the project's processes and outcomes. Other papers tackle diverse aspects of the project, including mental health matters in obesity prevention, changes in attitudes and perceived capacity for public and political action related to obesity prevention among adolescents participating in the project, and systematic reviews of system dynamics simulation models on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents; with this paper providing a full picture of the approach used to support co-creation by, and engagement with, young people in the context of obesity prevention policy ideas.

2 CONTEXT OF THE DIALOGUE FORUM TOOL DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

The design and development of the tool was led by EAT, a CO-CREATE partner, in collaboration with Designit, a research, design, and innovation agency subcontracted for this task. EAT is a nonprofit-based in Oslo, Norway, dedicated to transforming food systems through science and partnerships. Scientific research is at the heart of EAT's work and, with a network of universities and research institutions, it drives a shared objective of advancing knowledge about the nexus of food, health, and sustainability.23 Designit is a global design agency that specializes in diversity, equity, and inclusion, so products and services can better support diverse abilities, languages, cultures, gender, age, and other forms of human differences.24 The five research institutions across the participating countries (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, CEIDSS Centre for Studies and Research in Social Dynamics and Health, SWPS University, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and University of Amsterdam) also supported the development of the tool by engaging in testing, evaluation and feedback.

The aim of the Dialogue Forum tool was established before the start of the design process as part of the project's grant agreement and goal of engaging directly with young people — to develop, make use of, and evaluate a model for multi-actor dialogue forums, bringing together adolescents, policymakers, and businesses to action commitments and policies to enable healthy nutrition and physical activity habits for obesity prevention.

The design process started with an open and broad framing, with the following question: “How might we empower youth to drive the development of policies that enable healthy and sustainable habits?”25(p1) Before EAT selected Designit as their design partners through a public procurement process,25 the CO-CREATE consortium identified that a model for a multi-actor “dialogue tool” was needed, and that this tool would bring together adolescents, policymakers, and businesses to discuss obesity prevention policies developed by youth. The tool could take any form as long as it “truly reflects the needs and resources of youth themselves”25(p1) and that the design and prototyping of the tool included youth as part of the co-creation process. This design process was structured into five stages, described in the following pages: 1) research, 2) ideation and concept development, 3) design principles, 4) prototyping and testing, and 5) design iterations of models of the Dialogue Forum tool.

2.1 Research

The research included 30 semi-structured interviews and two workshops with members of the CO-CREATE project, expert representatives, academic, business, political, non-governmental organizations, and youth representatives of youth organizations in Norway, ages 14 to 18 years. No personal or demographic information was collected from the participating youth or stakeholders. All interviews and workshops were conducted with informed consent, and the participants received a copy of EAT and Designit's Privacy Policy. Designit's “do no harm” principles were applied to the entirety of the process, whereby sessions were designed and conducted with embedded ethics approved practices. The team also used the EU Horizon 2020 ethics checklist26 at the design stage of the interviews, with particular attention given to informed compliance, and recruitment of participants. Ethics approval was not sought for the interviews as they did not collect health or personal data and were not involved in health research, but rather consisted of consultations on youth involvement.

Interview candidates were identified based on their expert knowledge in youth inclusion and were invited through professional networks of EAT, aiming to engage as diverse and representative participants as possible, even though we recognize that by using existing networks to recruit, we hamper a fully diverse sample and therefore risk excluding certain groups as mentioned in the Discussion section. Existing local Norwegian youth organizations were used as proxies, while also serving as repositories of vast experience with engaging policymakers,25 as the project's Youth Alliances were not established yet (aiming to bring adolescents together across the five partner countries, to meet and exchange health policy proposals and organizational and processual experience). Designit together with EAT conducted the interviews, most face-to-face in Oslo, except for a few digital interviews with CO-CREATE project members located abroad. The interview questions covered broad topics regarding youth participation, youth inclusion, and youth and policymaking. Following the first four interviews, the interview guides were reiterated to adapt the questions to better understand how participants related to these broad topics of youth engagement in policy within their day-to-day experiences, such as participation and decision-making in everyday meetings. All interviews were transcribed live and anonymized by EAT and Designit.

Complementing the interviews, data was collected through two workshops. Press - Save the Children Youth Norway, a youth organization in Norway and partner of the CO-CREATE project, helped recruit youth organizations for these workshops. The first workshop was in Oslo with 15 youth representatives and openly explored topics that mattered to youth, together with youth inclusion in policymaking. The second workshop was with four youth representatives from important youth organizations in Norway: Press, Rural Youth, Youth Mental Health, and Spire. This last workshop focused on the scenario: “Mapping a politician's journey when involving youth,” as observed from the youth's perspective. The journey was analyzed through five stages: 1) reaching out to youth to engage in dialogue; 2) inviting youth to a dialogue session; 3) preparing for dialogue; 4) having the dialogue; and 5) following-up after the dialogue. Both workshops were facilitated by Designit and documentation was captured by EAT, and was later anonymized.

As it is common practice in design research, the data from the interviews and the two workshops were later synthesized using an abductive approach.27 An abductive approach to thematic analysis28 combines both an inductive approach (data-driven) and a deductive approach (hypothesis-driven). In this case, selected raw quotes from the interviews and workshops were transcribed by hand into physical sticky-notes. Then, the hundreds of sticky-notes were organized on a large wall and grouped into themes that emerged, by clustering the raw data and then re-organizing the data over time using a “journey map framework,” our hypothesis to further cluster the data in a linear way over time.

The design synthesis process can be described as “organizing complexity or finding clarity in chaos,”27 and an abductive approach, unlike deduction or induction, can allow for the creation of key insights.27 After many rounds of exploring the thematic clusters that emerged from the data, in combination with the journey map as a hypothesis to organize the data, 23 key themes were identified by Designit and EAT. As shown in Table 1, the first three insights belonged to general youth needs in the context of policymaking, while the remaining 20 insights were organized through four key moments in the politician's journey when involving youth, observed from the youth's perspective: 1) Invitation; 2) Preparation; 3) Meeting/Dialogue; 4) Relationships.

| General youth needs in the context of policymaking | 1) Invitation | 2) Preparation | 3) Meeting/Dialogue | 4) Strengthening relationships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

#01 Policymakers need to take us seriously, but not even our teachers and our parents do sometimes. |

#04 It's very rare to be invited. We usually invite ourselves. |

#10 We want to level the playing field; therefore, we need time to prepare. |

#13 We are invited to participate, but not heard. |

#19 If there won't be any follow-up, just tell it to my face, but don't leave me wondering. |

|

#02 Policymakers think we are all the same until they see us disagree. |

#05 Policymakers do not invite us because they are better safe than sorry. |

#11 We want to be treated equal, so don't give us our own kid's table. |

#14 When they are surprised by our abilities, they patronize us. |

#20 Our strength is that we can be professional friends off-court |

|

#03 Sharing youth personal stories with policymakers is a powerful tool, but it makes us vulnerable. |

#06 We are left out because involving us might give them more work. |

#12 Little things make us feel valued –like the “informal 5 minutes_ before, during or after the meeting. |

#15 It's hard to talk real beyond slogans. |

#21 Informal and personal communication can be more powerful and efficient than the formal routes. |

|

#07 If we are invited, we are invited in bulk. |

#16 When we meet, we mainly talk, but we want to do things together. |

#22 Knowing that I am not alone, makes it easier to put myself out there. |

||

|

#08 When we are invited, the purpose of the invitation is unclear. |

#17 When we ask obvious questions, pay attention, they can be transformative. |

#23 If we get mad, we don't want to make a fuss. But sometimes that's our only tool. |

||

|

#09 When we are invited, we never say “no”, even though we risk wasting our very limited resources. |

#18 We want to leave the meeting with clear action points. |

2.2 Ideation and concept development

- #07 When we are invited, we are invited in bulk (Invitation stage);

- #08 When we are invited, the purpose of the invitation is unclear (Invitation stage);

- #13 We are invited to participate, but not heard (Meeting stage);

- #18 We want to leave the meeting with clear action points (Meeting stage); and

- #19 If there will not be any follow-up, just tell it to my face, but do not leave me wondering (Relationship stage)

The workshop insights led to structuring the dialogue tool into a three-stage process, keeping in mind the goal of developing a model to connect youth and stakeholders to discuss and refine obesity prevention policy ideas: 1) preparation, 2) meeting, and 3) follow-up, and a checklist for each stage was conceptualized. In addition, three main roles were identified that would support, structure and lead the dialogue: 1) initiator & connector, 2) moderator, and 3) documenter and timekeeper.

2.3 Design principles

- For youth, by youth: Rather than centering conversation on matters about youth, youth should initiate, drive, and follow-up on the dialogue.

- Youth are plural: Move away from representing youth as having a singular perspective, and instead, bring together multiple different youth perspectives into the same dialogue to embrace their diversity of views.

- Invest time in the “unproductive bookend” moments: Instead of only focusing on the actual structured dialogue, provide ample time before and after the dialogue for participants to connect without an agenda, as this was identified as a key to building relationships.

- Make introductions personal: Starting by getting to know each other as people, and not only as stakeholders representing various interest groups, was found to be important to building trust across generations.

- Everyone's perspective matters: Instead of letting the most talkative participants take more space, structure activities and moderate the dialogue so all participants have equal amount of time to express themselves and be listened to. Recognize that each participant has something important to contribute, because of embodied expertise about their unique experience.

- Focus on desired outcomes: Instead of getting stuck discussing concrete ideas that might divide participants, focus on the “end goals” or that “larger purpose” that matter to each participant, which in turn, can enable alignment. Remind participants that ideas are only a means to achieve those broader ends, and that is why the dialogue needs to focus on the latter.

- Focus on doing (not only talking): Ensure every dialogue has a tangible impact, no matter how small, to ensure concrete follow-ups or actions.

2.4 Prototyping and testing

“A prototype should always be considered a learning vehicle providing more precise ideas about what the target system should be like.”33 Prototypes are different from pilots or full-scale implementations, as their main objective is to create something that can help general learning about aspects of a solution, by testing those aspects with people to observe or receive their feedback, learn, and adjust. The final Dialogue Forum tool took the shape of two models: a digital and a physical version. Three prototypes preceded the physical Dialogue Forum tool, and four prototypes informed the final design of the digital Dialogue Forum tool. Even though many of the prototypes were substantially different from each other, the design principles that emerged from the research and ideation phases embedded in all seven prototypes and in the two final versions of the Dialogue Forum tool. In the following passages we will describe the development of both prototypes and illustrate how the design principles resulted in an end product which satisfied the project's ambitions and contributed to our central ambitions of enabling youth participation in obesity prevention policy ideas, and ensuring that this participation includes actionable dialogues.

2.5 Prototyping the physical version of the Dialogue Forum tool

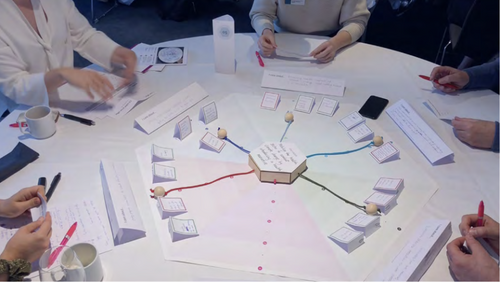

Prototype #1 was the first in-person or physical version of the Dialogue Forum (2019, Figure 1), created before knowing that a digital version would also be needed. This prototype put into practice the design principles that emerged from the research (Table 2). A real model of the tool was prototyped, to test aspects of the tool simultaneously as a coherent whole, in a real-life situation with real participants.

| Design principles: | Manifestation of the research-informed design principles |

|---|---|

| 1. For youth, by youth | It was important that youth host, moderate and take notes in the Dialogue Forum. For youth who had no previous experience in facilitating, we repeated the activity instructions for all the participants to follow along. This way anyone could jump in at any time and co-facilitate, if the main facilitator needed support. The development of moderator activity cards also allowed any participant, regardless of experience or training, to be able to moderate. |

| 2. Youth are plural | We had six participants per table, with equal representation of youth and adults, and multiple youth perspectives present at each of them. |

| 3. Invest time in the “unproductive bookend” moments | Time before and after the dialogue is built into the model to support establishing connections across the involved participants. |

| 4. Make introductions personal | Each participant identifies and shares a superpower in the beginning of the dialogue, allowing guests to rethink their abilities and their current or aspiring personal passion. |

| 5. Everyone's perspective matters | Participants fill in a card with what they care about the most in the context of the idea discussed, and share this with the group. Each participant has roughly the same amount of time to share after each activity. |

| 6. Focus on desired outcomes | Emphasizing the desired outcome that the idea is meant to achieve at the center piece; the idea and its potential implications are reframed as “enablers” of the desired outcome. This makes the conversation to be more inclusive of the diverse perspectives shared. |

| 7. Focus on doing (not only talking) | With the Dialogue Forum, participants identify steps that should be taken for the idea to be improved or taken forward; individual “support” cards with action statements turn talk into personal commitments to follow-up on conversations. |

Prototype #1 was first introduced as part of a side event of the Stockholm Food Forum in Sweden (June 2019) with 60 participants, where approximately half of the participants were youth. The aspects of the Dialogue Forum tool that this prototype tested were: six as the number of participants sitting around a round table; how easy it was to prepare and onboard a youth moderator role that could facilitate the dialogue; the 2 h timing for the dialogue; centering the conversation around a common shared vision, and having a physical and tangible manifestation of that shared vision in the center of the table; incentivizing constructive dissent, to avoid over-consensus, by creating a playful and tactile way to reframe different perspectives as strengths; and ending the dialogue with concrete action points, together with a structure to follow up.

The design principles (Table 2) are not only present in Prototype #1, but in all prototypes and in the final physical and digital versions of the Dialogue Forum tool.

2.5.1 Key learning and redesign suggestions for next prototypes

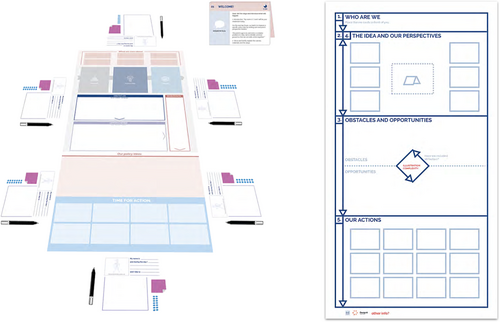

The learning from the first prototyping session was captured through a debrief conversation after the large-scale testing. This reflection session was mainly between the designers and the youth facilitators of the Dialogue Forum. The learning from the prototype testing was around aspects of scalability. Prototype #1 required a centralized production process, where the Dialogue Forum tool would be shipped as a complete package to “plug and play” in the different locations that it would be used. As this was a costly process, it was then redesigned in a way that the elements for the dialogue could be printed with affordable and accessible printers (using A4 and A3 paper size formats), in addition to readily available tools like sticky notes and markers. This learning informed the development of prototypes #2 (2020–2021, Figure 2, left) and prototype #3 (2021, Figure 2, right).

New versions of the Dialogue Forum tool were easier to scale to be used in different countries without relying on a costly centralized production system and shipping. The number of activities, roles, and type of facilitation flow,34 were only subject to minor changes, even though the look and feel of the tool changed significantly.

2.6 Prototyping the digital version of the Dialogue Forum

The COVID-19 pandemic diverted attention and resources away from the physical version of the Dialogue Forum, but led the project to develop a digital adaptation of the tool. Four prototypes were created before the final solution for the digital version of the Dialogue Forum tool was defined.

Prototype #1 of the digital Dialogue Forum tool (Figure 3, left) replicated the same structure and logic of the physical version in Prototype #2, and by testing it with real participants that were new to the concept, the designers quickly realized that participants struggled navigating the digital platform selected, which was Miro.35

Digital prototypes #2 and #3 of the Dialogue Forum tool (Figure 3, middle and right) moved away from using a specialized platform like Miro, and instead tested widely accessible and used tools like Google Sheets (prototype #2), and Google Slides and Zoom (prototype #3).

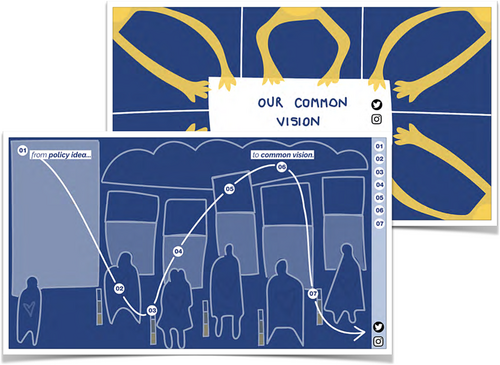

Prototype #4 of the digital Dialogue Forum (2020–2021) built on prototype #3, yet tried to make it more engaging by adding more experiential dimensions of design facilitation,34 such as ending with a common group photo of participant's hands holding “a common vision” (Figure 4, top). Another design principle identified was to always keep the overview in mind. To do this, one common digital canvas was used throughout the entire dialogue, where each activity built on each other by focusing on a particular section of the canvas, where at the end, the entire canvas was filled (Figure 4, bottom).

Prototype #4 was tested with over a hundred participants digitally joining from different parts of Europe. Learnings were captured through a digital survey, sent right after the dialogue. Feedback included perspectives of youth, academics, policymakers, business representatives, and civil society, and was provided by 44 participants (more than half being from youth). The main benefit shared was the opportunity to hear different perspectives and from diverse individuals, especially from young people. Participants particularly appreciated the interactive and inclusive nature of the Dialogue Forum that allowed everyone's voice to be heard, the ability to connect with people who have different experiences and expertise, and the discussions that developed. Overall, participants appreciated the safe space that the Dialogue Forum created to share opinions, the cross-generational nature of the tool, and the questions that sparked new ideas and challenged their own thoughts.

Respondents felt that the main areas that could be improved from Prototype #4 of the digital Dialogue Forum were greater inclusion of youth participants from different socioeconomic backgrounds, and encouraging more verbal exchange, discussion and building on each other's opinions. In terms of accessibility, feedback also included reducing text on the tool, more legible colors and larger font, and providing editing functions for text boxes instead of relying on Zoom's “annotation tools”.

2.7 Main learning from prototyping the physical and digital versions of the Dialogue Forum

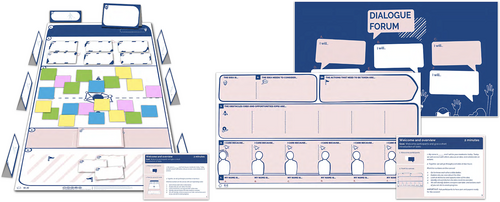

In 2021, a revision of the various prototypes was conducted to inform the design of the final Dialogue Forum tool, in both physical and digital versions. The purpose of the meta-revision was to integrate the insights obtained from participants (Appendix A) and organizers of 20 Dialogue Forums to produce even better-informed, more responsive and adaptive final models of the tool. To supplement this data, two additional evaluation workshops were organized with the project's Youth Task Force members, EAT staff, and other CO-CREATE consortium partners. After three prototypes of the physical Dialogue Forum tool and four prototypes of the digital Dialogue Forum tool, final versions were created, with coherence and consistency across design, aims, steps and materials for both the physical and digital formats (Figure 5).

- When it comes to broader applicability, the final version of the Dialogue Forum allows for the discussion of not only obesity prevention policy ideas, but also of other topics, which any user might be interested in addressing. The original version called specifically for revision of a policy idea that was brought to the Dialogue Forum, as a result of its use in the context of the CO-CREATE project. However, it left little space for actions in other contexts like communities and smaller groups. This “opening up” was tested on topics related to racial discrimination with a specialized group, yielding interesting and profound discussions.

- During the prototyping of the last versions, there were critiques around how the Dialogue Forum tool attempted to build consensus among the participants after reflecting on the obstacles and opportunities the participants noticed. These comments called for a more pluralistic way of addressing the salient points of the discussion, including highlighting the key elements discussed which were needed moving further, instead of aligning on a specific vision.

- The final version of the Dialogue Forum tool has subtle yet significant differences that build on the strengths of the initial tool, both in form and structure. In terms of form, the limitations of the digital and physical formats yield in slightly different visual layouts: the physical version of the tool retained its linear, canvas-like structure that the participants build on as they engage in the dialogue. The digital Dialogue Forum tool was adapted to a screen-friendly setup that can be built up in a similar way to the physical version. In terms of outcome, the physical and digital tools were aligned in their structure: 0) Introductions of the topic or ideas, 1) introduction of the participants, 2) why they care about the topic, 3) the obstacles and opportunities the idea or topic presents, 4) discussion and highlighting of what the idea needs to consider, 5a) actions that need to be taken, and 5b) concrete actions moving forward.

- As a way to see broader opportunities among the group, step 5a, “The actions that need to be taken are,” invites participants to see what actions can be taken by different actors across the systems connected with the topic being discussed. These actors can range from entities, communities or individuals, and can help the group get in touch with them as follow-up actions. This revision recognizes that while all participants at a dialogue can take individual action, certain external actors yield significant power to change the issue and should be engaged.

- In connection to step 5a, step 5b “concrete actions moving forward”, continues the Dialogue Forum's strength of arriving at actionable steps to be taken after dialogue. In the final iteration, participants are invited to determine a small yet actionable step to do within a self-established time period. The reasoning of using a timeframe is to give specificity to the task that needs to be done, aiming to increase the probability of it being completed.

To summarize, the highest contrast between the initial prototype and final versions of the Dialogue Forum is visible in their structures. The final version can be applied to any idea or initiative beyond discussion of obesity prevention policies, but its core retains the seven principles for youth engagement, outlined from the initial research and ideation phases (Table 2). The full Dialogue Forum package was published on World Health Day, April 7, 2022, as open source material that is free that anyone can download and use from the CO-CREATE website, EAT website and Healthy Voices website. Both physical and digital versions of the Dialogue Forum tool can be downloaded, along with a step-by-step guidebook, and a set of four instructive videos and a social media teaser video.

3 DISCUSSION

In the initial research phase of the Dialogue Forum tool, it became evident that young people wanted to be taken seriously in policy venues and lacked concrete, tangible, and user-friendly tools to proactively engage with decision-makers on the topic of health and obesity prevention; there was also a lack of a structured dialogue tool and discussion framework to engage youth, reflecting the existing irregular youth engagement environment.11, 12 The Dialogue Forum aimed to solve both issues. Through the research and prototyping process, as well as testing of the tool through 20 Dialogue Forums held virtually and across five European countries, the tool achieved its original goal of providing an inclusive model for multi-actor dialogue, enabling discussions of policy ideas for healthy nutrition and physical activity environments to support obesity prevention.

An important part of the Dialogue Forums is its action-oriented nature. Through the step-by-step process, participants are guided from an idea to actions they can take to further the policy idea. In the project's 20 Dialogue Forums, a variety of stakeholder groups were invited to participate, because of their different expertise and resources to support the young people and their policy ideas. This led to a diversity of perspectives in refining and improving policy ideas. Through the Dialogue Forums, participants committed to actions, which were shared in project Deliverables36, 37 and webpages,38 providing an overview of the commitments from the stakeholders who participated and offered to support the youth-led policy ideas.

While it is too early to comment on the long-term benefits of a participatory model within a health outcome lens, initial positive results were recognized following Dialogue Forums. Examples of commitments included helping to run a cookery club, offering coordination between schools, indicating potential sources of financial support, or facilitating contacts within the industry.37 Examples of outcomes included Portuguese stakeholders inviting the Youth Alliance to present its policy ideas to City Hall, and a Norwegian politician asking the Minister of Health to consider drafting a bill to ban the advertising of unhealthy food and drinks on digital platforms aimed at children under the age of 18 years.37 Additionally, through the Dialogue Forums, young people identified and elevated four obesity prevention policy demands to EU policymakers through a Youth Declaration39: 1) stop all marketing of unhealthy food products to children under the age of 18, 2) ensure all children access to high-quality, practical based food and nutritional education in school, 3) implement a sugar sweetened beverage tax and 4) offer free and inclusive organized physical activity programs for all children and adolescents at least once every week. The 20 Dialogue Forums provided space and opportunities for youth to meet relevant and influential stakeholders, as well as have their diverse voices heard in proposed solutions of the obesity epidemic, making them more relevant for youth. Overall, the design of the Dialogue Forum tool supports meaningful youth engagement and potential shifts in stakeholder perspectives.

Measuring outcomes and impacts of Dialogue Forums proved to be challenging. Through the development of the conflicts of interest framework,21 it was deemed high-risk to facilitate direct youth and adult stakeholder engagement post-dialogue. Country partners were responsible for facilitating follow-up and for tracking progress, which led to various outcomes. The process of implementing and evaluating the Dialogue Forums gave insight into the need to facilitate better follow-up mechanisms into the Dialogue process itself, and to recognize that participants must be accountable for follow-up, independent of organizers.

Overall, the design process and development of the Dialogue Forum tool supported CO-CREATE's objective of providing a model to involve young people and relevant stakeholders on specific obesity related youth-led policy proposals. The Dialogue Forum tool provides policymakers with an explicit, safe and inclusive tool to engage young people, and likewise, enables youth to engage in formal policy processes, helping secure their right to participation – supporting benefits to both young people and policymakers.12 A long-term study following-up on outcomes from Dialogue Forums would prove useful in confirming the tool's potential to positively affect policies that promote healthy food and physical activity environments for young people.

3.1 Strengths and limitations of the Dialogue Forum tool and its design process

- It is a dialogue tool designed with and for youth, and has a particular potential and value for young people or youth organizations looking to engage decision-makers or other stakeholders to increase awareness and action on an idea that has consequences for youth.

- The tool and accompanying content provide clear steps and guidance for decision-makers and other stakeholders in the public or private sector who are looking to engage and meaningfully involve young people in the design, implementation or evaluation of interventions or policies.

- Each step of the Dialogue Forum is centered in co-creation, and collaboration tends to increase as the session progresses. The tangible nature of the tool also allows participants to document the discussion as they progress through the dialogue. This provides participants with the ability to build on a discussion, and organizers the ability to analyze and report afterwards.

- The digital Dialogue Forum has the advantage of online meetings, which can facilitate access for both youth and stakeholders who may not otherwise have time or resources to attend physical gatherings. This broadens accessibility of the tool.

- While there were a number of examples of young people connecting with stakeholders after the Dialogue Forum, there were few very tangible outcomes and short-term impacts.

- Most of the research was recruited through networks of the project partners, so the tool might not address the full spectrum of diversity and inadvertently exclude some perspectives.

- Most of the testing was done in a European (Global North) context, so the global applicability of the tool can be questioned.

- The COVID-19 pandemic diverted attention and resources away from the physical version of the Dialogue Forum, but led the project to develop a digital version of the tool.

3.2 Adaptability

- Translation: The tool was designed with minimal text, making translation easy. Through the CO-CREATE project, the Dialogue Forum and affiliated materials were translated into Dutch, Polish, Norwegian, Swedish, Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, French and German.

- Adaptability: While the steps of the tool are broad enough to address a range of issues, policies or interventions, the limited text on the tool makes it easily adaptable. Given the flexible nature, its application and use is quite broad.

- Building on youth engagement infrastructure: Meaningful youth engagement is not a novel concept, however, the degree to which governments and decision-makers implement this varies significantly. The Dialogue Forum can help build on existing infrastructure for youth participation by providing decision-makers with a tangible tool and process by which youth can be meaningfully engaged in decisions that affect them.

- Adoption by youth organizations: Throughout the project, engagement with youth organizations has proved valuable in broadening outreach to youth, and increasing impact beyond the Dialogue Forum and CO-CREATE project.

4 YOUTH PERSPECTIVES ON THE DIALOGUE FORUM

The following section has been written by two youth who were actively involved in the development of the Dialogue Forum tool, including personal views and comments on their experience:

As youth involved in the CO-CREATE Project, we got to witness the creation and development of the tool. Since our feedback was heard, we can confirm that the tool was made for youth, with youth.

Within this process, we had the opportunity to have dialogues with different stakeholders. We used the tool with a wide variety of people: from local stakeholders to politicians, but also professionals from various sectors and European changemakers.

During the Dialogue Forum sessions, we felt a safe environment. Since the tool is designed to establish an equal discussion and an equal seat at the table, the stakeholders talked to us with a different attitude. They were trying to learn from us, as much as we were learning from them. After all, this is what intergenerational discussion is about. Youth cannot change the world on their own, and politicians cannot make everyone happy without putting themselves in everyone's shoes. So, if a policy idea affects youth, youth should be consulted.

With time, we quickly realized the power of this tool. This could be targeted to different groups, it is not specific to obesity-related discussions. The tool creates an environment where a group of people can have an organized discussion, where the sequence of actions is productive and natural, allowing the conversation to flow very easily among the participants. In addition, it is very intuitive: the participants easily know what to do in every step. After all, this is the best way to create discussion. Dividing a big task into small ones.

If we needed to summarize this tool in one word, the one that comes to mind is important – it allows a different and a new type of discussion, giving the space and the time for young people to make themselves heard, but also to hear the stakeholders, creating a friendly environment, based on sharing experiences and advice.

5 CONCLUSION

Multiple prototypes of the Dialogue Forum tool were tested with more than 200 participants from 53 countries in over 20 Dialogue Forums. From this, a final digital and physical version of the Dialogue Forum was published. Through the CO-CREATE project and beyond, the Dialogue Forum has been used to connect people across generations and sectors, in an effort to co-create solutions to prevent childhood obesity and build healthier environments. Although the tool has been translated and adapted in other contexts, this primary goal of allowing people to connect and collaborate on actions has remained consistent. While other dialogue tools exist, the CO-CREATE Dialogue Forum tool is novel in that it is the product of a three-year long systematic and documented process of testing, prototyping, and refinement, involving youth throughout. The tool has been used in local schools and in high-level United Nations meetings, in Malawi and Portugal, by 14-year-olds and by CEOs, and incorporates the feedback from these different people and settings. We have made it freely available, and we hope it will help youth around the world to have their voices heard.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The “Confronting obesity: Co-creating policy with youth” (CO-CREATE) project received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No.774210 https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/774210). The content of this document reflects only the authors' views, and the European Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information it contains. The authors would like to recognize the contribution of all youth participating in the CO-CREATE project as central to the development of the Dialogue Forum tool, as well as previous colleagues in the project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest statement.

APPENDIX A: LIST OF 23 KEY INSIGHTS FROM RESEARCH

| General youth needs in the context of policymaking | Quotes from interview participants |

|---|---|

|

#01 Policymakers need to take us seriously, but not even our teachers and our parents do sometimes. |

“Young people don't have the same legitimacy in policy processes. Many include us to tick the minority boxes.” youth “I told her [my teacher] that I wanted to take the hardest courses in high school and get the job I wanted. She didn't believe in me. I felt like I couldn't do it, or she made me feel like couldn't do it.” youth “Often when we discuss politics the discussion turns into undermining laughter. One time we discussed tolls and they laughed at me. I felt annoyed and offended, and at the same time, I felt small.” youth |

| #02 Policymakers think we are all the same until they see us disagree. |

“The only thing we have in common is that we are undervalued.” youth leader “Politicians benefit from seeing us argue. They have an idea of us being one group. But I enjoy showing adults the we represent multiple voices.” youth leader |

| #03 Sharing youth personal stories with policymakers is a powerful tool, but it makes us vulnerable. |

“If you are a charismatic leader, you get invited to more meetings. If you have a personal story to share, they usually invite you because they want that story.” youth leader “Our job is to protect people from sharing too much of their personal stories. We should talk about the issues, and then bring the stories to that issue. And not the other way around.” youth leader “Foundations collect stories from youth. But they don't have democratic rights like us. That's problematic because they have a lot of influence, politicians love stories that move people. But we can't compete with that, and it's not ethical to use people's stories in that way.” youth leader |

| Step 1 in Dialogue: INVITATION | |

| #04 It's very rare to be invited. We usually invite ourselves. |

“It's very rare to be invited. We usually invite ourselves. The few times we are invited, it's in bulk with many other youth organisations — and very official. Usually by email.” youth leader “Children and youth are difficult to reach for involvement. Choosing recruitment strategies is difficult.” policymaker |

| #05 Policymakers do not invite us because they are better safe than sorry. |

“They are scared of youth organisations. We are good at making us heard if they do something wrong.” youth leader “Instead of assuming that children are especially fragile, we need to know what to do in case something goes wrong.” policymaker “It needs to be a “safe space” — that's a word adults say a lot. We are already safe.” youth leader “They might be afraid of doing things the wrong way. Then they are also scared of the backlash.” youth leader |

| #06 We are left out because involving us might give them more work. |

“It might require more planning and preparation.” youth leader “It's easier for politicians to involve youth organisations that focus on a certain topic when they need that expertise, like mental health. It's hard for them to know that most youth organisations address mental health, especially those who have a broader scope.” youth leader |

| #07 If we are invited, we are invited in bulk. |

“How do we reach the right stakeholders, without needing to include all?” policymaker “Children and youth are difficult to reach for involvement. Choosing recruitment strategies is difficult.” policymaker “My organisation's purpose is so broad, it's difficult for politicians to involve us.” youth leader |

| #08 When we are invited, the purpose of the invitation is unclear. |

“Politicians have to be honest with youth and realistic about what they can achieve together. There needs to be a translation of power — handing over responsibility to youth.” co-create member “We need to be upfront about the purpose of engaging. Is it for getting feedback on solutions or framing challenges? There's a difference between asking “do you like this website?” or “how is the best way to reach you?” bureaucrat “Youth are usually invited to give input into existing processes, but never to help decide on what to focus on.” youth leader |

| #09 When we are invited, we never say “no”, even though we risk wasting our very limited resources. |

“It's very hard to say “no” because then you lose being invited again.” -Youth leader “We are paid extremely little and work harder than anyone else. But I don't want people to pay me. Our job is to represent our members and money would only distort that. But we need to feel valued.” -Youth leader “Experience-based knowledge is not valued as much as academic and working experience. So youth are not compensated for their time. But when politicians invite experts, they are compensated a lot.” -Youth leader “Why should we use our resources in this when we know what we say won't be taken seriously? Politicians often end up eating our resources.” -Youth leader |

| Step 2 in Dialogue: PREPARATION | |

| #10 We want to level the playing field; therefore we need time to prepare. |

“If they send out an agenda and prepping material in advance, it's only two days ahead. That always makes you feel unprepared. You end up prepping last minute, or you lose sleep. And if others have more time to prepare, you are in a disadvantage.” -Youth leader “I would prepare politicians before they talk with youth. They need to empathise with the fact that they are speaking for the first time, so it has to be a good experience.” -Youth leader You cannot just speak and have a voice. You cannot put 5 unexperienced youth with 5 CEOs. They need a common language, that's why we'll focus on training.” -CO-CREATE consortium member “I would prepare young people before talking to politicians. I would boost their confidence about speaking, not only about themselves, but also about the people they represent.” -Youth leader |

| #11 We want to be treated equal, so do not give us our own kid's table. |

“We are not seen as equal partners. We get our own meetings, but never central stage in adults meetings. Very frustrating.” -Youth leader “Everyone came prepared for the old structure - but when we went to the loft it was very laid back. They ordered pizzas and sodas. It felt like we were treated like children.” -Youth leader “Creative formats work if you are like 10 yrs. old. But for us working in youth organisations for over 10 years, we find it demeaning to be treated like children.” -Youth leader “I enjoy youth-focused meetings, because then we don't have to listen to adults all the time. But if feels like a bad consolation price [to get our own table].” -Youth leader “Sometimes we're asked to sit close to the front to appear in the pictures, but that doesn't mean we are given a chance to speak.” -Youth leader |

| #12 Little things make us feel valued –like the “informal 5 minutes_ before, during or after the meeting. |

“If I were a politician, I would talk about the most pressing issues. I would prepare my team to be present to take notes.” -Youth leader “Politicians were there 5 minutes before the meeting started, just to meet us. That made me feel important.” -Youth leader “Initially we got 30 minutes [with the Minister], but then got 45 minutes to talk about what we wanted and focused on three areas. They suggested we run the show and gave us great feedback. Then they suggested a follow-up meeting.” -Youth leader “In addition to being prepared – the room, food, equipment, tech - was all ready. Those little things matter. They listened, they were interested, and it felt productive. This wasn't just symbol politics - we were there to do a job, youth organisations, the Department of Health, and other experts altogether.” -Youth leader |

| Step 3 in Dialogue: MEETING | |

| #13 We are invited to participate, but not heard. |

“It was basically 60 young people talking to each other and no one really listening.” Youth leader “One step for a better future for us is to be taken seriously. If we have something important to say, we want to say it in those settings.” youth leader “When we met with the Minister, there were only grown-ups talking. We were 5 youth organisations and no one got to speak. Seeing youth on the same side as everyone else is a good place to start.” -Youth leader “I think adults should start thinking more about child participation in the same way as adult participation. [Currently] they think that if they involve children they are the ones who have to decide [for them].” -Youth leader “It's important that youth not only get a seat in municipalities' youth councils but that they also have the power to impact the agenda with what's important to them.” -Researcher “I know I can be seen as the “complaining bitch” in a meeting. But that is kind of a role I have taken because it can give results as well.” -Youth leader “Didn't feel like we were given the opportunity to give input. Felt very forced. We were 60–70 people in a room so that wasn't the space for real conversations.” -Youth leader |

| #14 When they are surprised by our abilities, they patronize us. |

“Sometimes people patronise us “oh… you are so smart, so good, you!” Just because we came prepared to a meeting.” -Youth leader “We don't like when adults are condescending.” -Youth leader “When I lead and facilitate meetings, people react differently. Many are not used to a 20-year-old leading an organisation. It is unexpected.” -Youth leader “They don't mean bad, but they just never relate to young people as peers.” -Youth leader “Don't applaud youth if you're not going to do anything about it.” -Youth leader |

| #15 It's hard to talk real beyond slogans. |

“We need youth to care about the matter and not just the slogan. Youth are intelligent enough to understand.” -Youth leader “How do we know if what we hear is what youth really want to say? Things may get lost in translation.” -Policymaker “We cannot only have slogans but we need to understand the complexities beneath the slogans.” -Youth leader “Avoid prepared statements. Talk instead. It is so much more fun to have a dialogue on equal terms.” -Youth leader “There were vested interests at the table, not declared, but obvious. We all disagreed but discussed in a way we could even joke about it.” -Business leader “You need room to lay out the arguments. All people must be heard and understand their different viewpoints. You shouldn't aim for consensus but get rid of misunderstandings and identify the big issues.” -CO-CREATE consortium member |

| #16 When we meet, we mainly talk, but we want to do things together. |

“We are sick and tired of talking about why we should talk about politics - rather than just talking about it.” -Youth leader “Are we going to sit once more to talk about this? We need to DO. We often agree on the end goal, but never on how to get there.” -Youth leader “Workshopping with politicians should become a natural way of working together. And not just youth, but with businesses and other stakeholders too.” -Youth leader |

| #17 When we ask obvious questions, pay attention, they can be transformative. |

“What youth can be extremely good at is asking difficult questions – pointing to the many dilemmas in our modern western consumer lives based on what they see and experience. Many of them are eminent observers – and still ask questions we adults have stopped asking.” -Public service provider “Young people have a very different angle and they can challenge our business models and solutions. Maybe having a youth-led forum can become our competitive edge.» -Business leader “At the moment we only communicate only over email, and in a way I've had to learn how to work more that way. I have had to be much more disciplined to check email after I joined the panel of experts.” -Youth leader “It's really impressive to challenge grown-ups' worldview.” -Youth leader “My biggest source of inspiration comes from my two boys, 12 and 15, and they both participated in the demonstrations last week. They hold me accountable for the car I use and how much plastic we have at the breakfast table.” -Business leader |

| #18 We want to leave the meeting with clear action points. |

“I want to leave a meeting with clear action points. With many meetings and a hectic schedule, I need to be able to track back to decisions.” -Youth leader “It's very hard for a single member to change the direction of our organisation. As all decisions are voted upon in our annual General Assembly.” -Youth leader “We report on what is decided in the General Assembly. Like our goals, activities, and number of members we want to reach this year. Then we use these metrics to look back and evaluate our year.” -Youth leader “We do not have a good way to document things on a day-to- day basis. And we have a lot of turnover of staff.” -Youth leader “We need minutes from the meeting. They never give them to us.” -Youth leader |

| Step 4 in Dialogue: STRENGTHENING RELATIONSHIPS | |

| #19 If there will not be any follow-up, just tell it to my face, but do not leave me wondering. |

“Everyone was very happy after, but there was no plan for following-up.” -Youth leader “Most of my disappointments are related to decision-makers not following-up.” -Youth leader “Many meetings should send me an email saying “thank you, you said this, and this is what we did about it” - so I can agree on it.” -Youth leader “If nothing comes out of the meeting, tell it to my face. If you don't agree, or will not do anything with my involvement, just tell me.” -Youth leader “I've never heard a politician say “I disagree”. They just say, “this is a very nice input”. And then disappear.” -Youth leader |

| #20 Our strength is that we can be professional friends off-court. |

“It's ok to be friends with people you really disagree with. Leaders of political parties are very good friends outside the debate. This is why Norwegians trust the political system. We are people and treat people like people, no matter if we have different ideologies.” -Youth leader “That's what we learn in youth organisations since we are like 12. We can be friends and still debate.” -Youth leader “The most valuable lesson from party politics is that I don't have to agree with everything to support the party. The choice to participate in the process is important, then you respect the outcomes more.” -Youth leader |

| #21 Informal and personal communication can be more powerful and efficient than the formal routes. |

“With the politicians I know, we communicate informally - with funny memes in our emails. This is more efficient than being formal.” -Youth leader “I can text the Minister of Education whenever I want. But we have a professional relationship. We can inform each other of things, but if he does something wrong, he knows I'll call the media.” -Youth leader |

| #22 Knowing that I am not alone, makes it easier to put myself out there. |

“There should be just as many youths as adults around the table. Youth need to feel that they are one among many. To put one young person in a room with many adults and expect them to answer difficult questions has little value and is not efficient, as it makes youth uncomfortable. That's my experience, at least.” -Youth leader “I am, still, completely dependent on having youth around to feel comfortable. So if adults want to include youth in their work, then they have to meet them in a completely informal, unconventional way. Ideally, it should be the adults who break their routines to meet youth, not the other way around.” -Youth leader “I am used to, have adapted to, the role of “youth” where I am meant to participate instead of decide, especially in settings where there are adults present. And that's just the way society is built… We have to take on a role where we support adults, where there's not a power struggle between who should have the greatest power, because that's a fight we simply will not win.” -Youth leader “We should try to tell youth that it's normal to have a tough time, without being condescending. To say “Yes, that's life, and you will get through it. But there's nothing wrong with how you feel. It's just how things are. And I feel for you.” -Youth leader |

| #23 If we get mad, we do not want to make a fuss. But sometimes that's our only tool. |

“We make Instagram stories. In this case, we were all excited about how we were going to be heard. When that didn't happen, we made a sad follow-up story about how we weren't heard. That was picked up by the Christian Democrats who decided to do something about it.” -Youth leader “We also have to focus on being legitimate, we are not just running around making a fuss.” -Youth leader “Calm dialogic approaches can sometimes work - they build trust - like the time we talked to the Minister's Advisor. But not contacting the media can also give the impression that we don't get mad.” -Youth leader “Sometimes they [youth] are polite, sometimes they rebel and undermine their process.” -NGO |