Developing a theoretical definition of self-organization: A principle-based concept analysis in the context of uncertainty in chronic illness

Abstract

Aim

To develop a theoretical definition of self-organization to increase the understanding of the Reconceptualized Uncertainty in Illness Theory (RUIT).

Background

Mishel described the change of the uncertainty appraisal over time in people with a chronic illness by means of the RUIT. Therefore, she introduced the concept of self-organization. However, its meaning is difficult to comprehend because its descriptions remained highly abstract.

Design

A principle-based concept analysis.

Data Source

Entries of lexicons and journal publications, explicitly or implicitly addressing self-organization in the context of any social phenomenon.

Review Methods

We conducted a conceptually driven literature search in lexicons and four databases and performed citation tracking.

Results

Self-organization stands for a transition between psychological instability and psychological adjustment. It is conditioned by illness-related obstacles or uncertainties that are perceived as life-threatening. This adaptation process shows overlaps with cognitive reframing and is promoted by time, resilience, social support, and positive development of the disease. It leads to empowerment and a new perspective of life and uncertainty.

Conclusions

We enhanced the understanding of the RUIT by developing a theoretical definition of self-organization on a lower level of abstraction and by proposing a new approximation for the operationalization by means of cognitive reframing.

1 INTRODUCTION

Theories and concepts in nursing are conceptualizations of a part of nursing reality. They are generated for the purpose of describing phenomena, explaining relationships between them, predicting consequences or making recommendations for nursing interventions.1 However, nurses face challenges in terms of applicability in clinical practice as well as in academia due to the undifferentiated nature of existing theories, insufficient explanatory power, and lack of evaluation. Following, theories should be continuously analyzed, tested, and modified.2 By highlighting weaknesses and opportunities for evaluation, a theory can be further developed. Such further development can include clarification, refinement, and extension of a theory.3

The theoretical work on uncertainty in illness by Merle Mishel sets an example of such a further development in theory building. She extended her well-known and established Uncertainty in Illness Theory (UIT)4 to the Reconceptualized Uncertainty in Illness Theory (RUIT).5 The RUIT is a middle range theory on the uncertainty evolution during the course of a chronic condition. According to Mishel,5 continuing uncertainty becomes the starting point for reformulating one's view of life over time. This process is expressed by the concept of self-organization. Becoming self-organized is characterized by appraising uncertainty as an opportunity and no longer as a danger.5 Such a potential development should be acknowledged in nursing practice and research to support a positive view on uncertainty in patients. However, the description of the concept of self-organization in the RUIT remains abstract and on a meta-theoretical level. Therefore, the understanding and application of this middle range theory is limited. This may significantly limit the understanding of the phenomenon in the real world and slow down theory dynamics and research in the context of uncertainty in chronic illness.

2 BACKGROUND

Mishel developed the UIT4, 6 to explain how patients cognitively structure a subjective interpretation of uncertainty regarding treatment and outcomes in acute illness.4 According to her, uncertainty manifests itself in illness situations that are unclear, complex, and unpredictable. Uncertainty is defined as the inability to assign meaning to disease-related events.4 The theory results in a return to the previous level of adaptation by eliminating uncertainty.5 Mishel extended the UIT to the RUIT, inspired by qualitative data from chronically ill individuals and by the awareness of the original theory's limitations. She added the concepts of self-organization and probabilistic thinking to explain the change of the uncertainty appraisal in chronic illness. Both concepts lead to a new value system and shall explain the reappraisal of uncertainty from danger to an opportunity.5

To extend the RUIT, Mishel applied the process of theory derivation by Walker and Avant7 and selected Chaos Theory as parent theory.5 Chaos Theory is originally assigned to the field of applied mathematics and deals with orders in dynamic systems.8 According to Chaos Theory, self-organization occurs within systems that are far from a stable order.9

Regarding the application of Chaos Theory to uncertainty in illness, Mishel proposed in a vague and abstracted manner that uncertainty surrounding a chronic condition can be interpreted as a fluctuation that threatens the pre-existing organization of a person.5 According to her self-organization in this context begins “at the time of disorder at the macroscopic level, when the uncertainty appears the highest”.5 Thus, self-organization leads to the occurrence of “some early structuring of a new value, imperceivable but existing at the microscopic level”.5 Mishel defined self-organization as the incorporation of enduring uncertainty into one's being so that it is accepted as part of life, resulting in a “new sense of order”.5 This shift in thinking was reported in several studies examining the process of living with uncertainty in different patient groups.10-17 Although there has been significant research on this topic, the actual development process of self-organization remains unclear. This may result from the fact that previous investigations focused mainly on the specifics of self-organization and its outcomes in multiple different health contexts, rather than on the process of self-organization as such.

Therefore, the concept of self-organization and its meanings for the general process of positively reappraising uncertainty over time are difficult to comprehend. In principle, the progress of theory development and scientific knowledge depends on consistent terminology.18 To avoid misunderstandings and to promote advancement in nursing theory, research and practice, theories and their concepts should be clear and unambiguous.19

Against this background, conceptual clarification is necessary to ensure that nurses and other health care professionals understand the information that the RUIT provides, and that this information can be useful for research, practice and theory dynamics.

3 AIM

The aim of this study was to analyze the existing state of science of the concept of self-organization and to develop a theoretical definition to enhance the understanding of the RUIT.

4 DESIGN

Several nursing scholars1, 20-24 as well as philosophers of science25 argue that concepts are essential components of theories and that the clarification of concepts promotes theoretical thinking. In this sense, we conducted a concept analysis to clarify the concept of self-organization.

We chose the principle-based approach by Penrod and Hupcey22 because it results in a theoretical definition of a concept, thereby supporting theory development through the formation of a more meaningful and consistent theory. This is achieved by determining potential pathways for concept advancement.22 After Morse et al. have proposed this method,26 it has been further developed by Penrod and Hupcey.22 They departed from classifying a concept as mature or immature as a result of concept analysis.22 Penrod and Hupcey consider scientific literature as “the best estimate of probable truth” of existing theoretical strands that define a concept. Consequently, the authors did not include evidence found in art or nonscientific literature.22 Instead, they specified evidence regarding a concept based on four philosophical principles.

However, this method was also chosen because it emphasizes multidisciplinarity. Mishel's theories have been used in several disciplines with different interpretations, extensions, and applications.27 Mishel herself had an academic background in psychology.4 According to Penrod and Hupcey22 a multidisciplinary perspective is particularly important in nursing since related disciplines can contribute to the understanding of a concept in nursing due to shared paradigms. In the principle-based approach multiple perspectives are considered by analyzing a concept across the scientific literature of different disciplines.

- (1)

The epistemological principle concentrates on the discipline's perception of a concept within the knowledge of the scientific community. It involves the examination of how the concept has been explicitly and implicitly defined. By means of these definitions, the concept should be clearly differentiated from other concepts.

- (2)

The pragmatic principle is focused on the applicability of the concept for explaining or describing a phenomenon within the discipline. The analysis also involves the question whether the concept has been operationalised. The concept should enable members of the discipline to identify manifestations in practice.

- (3)

Following the linguistic principle, the appropriate use of the concept in use and meaning and the fit of the concept within context is analyzed.

- (4)

The analysis by means of the logical principle focuses on conceptual boundaries when positioned theoretically with other concepts.

4.1 Review methods

We conducted a conceptually driven literature search in April 2020, including entries of lexicons and dictionaries, journal publications, and scientific books. We searched the online versions of multiple lexicons and dictionaries and the following databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus. To keep the search as sensitive as possible, the search strategy consisted only of the component “self-organization.” We used a thesaurus and keyword catalogs of the different databases to identify synonyms and keywords. Since controlled vocabulary and synonyms were not available, our search strategy consisted only of the term “self-organization” using database-specific search commands, wildcards and phrase searching. We also integrated other spellings of the terms, such as “self organization,” “self-organization,” and “self organization” and the German translation “Selbstorganisation” into the search strategy. There were no restrictions on the publication date, nor on the study design. Literature in the field of nursing and other health and social sciences disciplines explicitly or implicitly addressing self-organization in the context of any social phenomenon was included. Though, only those implicit text passages were considered that were in the context of uncertainty, where for example, a shift in thinking, growth through uncertainty or new life values were described, according to the descriptions of the RUIT.5

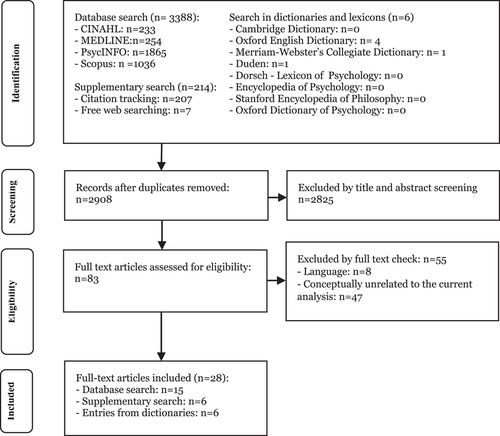

Additionally, we performed backward and forward citation tracking of included studies, and free web searching via Google Scholar. Figure 1 shows the process of identification and selection of the literature.

4.2 Analysis

Text passages of the included literature addressing self-organization explicitly or implicitly were selected for analysis. Data analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke's28 reflexive thematic analysis, because this approach involves theme development from inductively generated codes, which are “conceptualized as patterns of shared meaning underpinned by a central organizing concept”.29 This was especially important to be open for new insights of the concept on the one hand but also to organize the data and get deeper insights on a theoretical level with the help of the philosophical principles according to Penrod and Hupcey22 on the other hand. First, we descriptively and openly coded the literature grounding from the data. Afterwards, we thematically linked the codes as subcategories specifying the appraisal of the principles. Furthermore, to get deeper insights into the concept's constructs of self-organization we orientated on Grounded Theory's coding paradigm30 for theoretical coding. Thereby we aimed to illuminate characteristics, antecedents, influencing factors, and consequences, which were not explicitly considered by Penrod and Hupycey.22 At first, we analyzed the concept within the nursing literature. Afterwards, we examined the combined evidence from the other disciplines. In a final step, we analyzed the whole data set across all disciplines using constant comparative method,31 thereby identifying similarities and differences. Finally, we developed a theoretical definition by synthesizing the central findings associated with each principle and the theoretical coding.

5 FINDINGS

5.1 Data sources

The search yielded 28 relevant hits, including 6 dictionary entries, and 22 journal publications. Of these articles, 14 were in the field of nursing,6, 15, 17, 32-42 one in psychology,43 three in communication science,44-46 one in social work,47 one in rehabilitation medicine,48 one in public health,49 and one in social sciences.50 They were published between 1988 and 2020 and performed in Australia (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), Europe (n = 6), and the United States of America (n = 13). The majority were qualitative studies (n = 15), followed by concept analyses (n = 3), discussion articles (n = 2), and quantitative observational studies (n = 2).

5.2 Epistemological principle

5.2.1 Nursing literature

Monsivais10 referred to self-organization as a process of learning to live with and adapt to chronic illness. Other authors defined self-organization as a patterning balance between illness-related certainties and uncertainty17, 47 and as balancing an uncertain future in a broadened life perspective.15 Self-organization means moving from one state of (un)certainty to another34 or from one perspective of life to a new one.15 According to Hilton,35 it is a continuum between surety and vagueness. The majority of the literature in nursing thematising self-organization orientated to Mishel's RUIT as theoretical underpinning.6, 10, 15, 32, 33, 39, 40 Hilton,35 however, referenced to Lazarus and Folkman's51 cognitive-phenomenological model of psychological stress as conceptual framework and Neill52 to Margaret Newman's theory of Health as Expanding Consciousness. Furthermore, hermeneutic phenomenology served as methodological framework.37

5.2.2 Literature of other health and social science disciplines

Self-organization concerns social systems, such as individuals or groups, passing from disordered phases to more complex orders.43 According to Skar43 (from the field of psychology), it means returning to a pattern of a stable state. This includes the adaptation to changing conditions due to instability, thereby creating new structures and modes of behavior.43 Self-organization brings (a new) order out of chaos.53

In communication sciences, self-organization is defined as the imposition of order by understanding and adapting to chaos.45 In social work, however, self-organization is described as a transition from coping to transformational, psychospiritual growth, as well as from managing uncertainty to recognizing certainties. As a result, self-organization exists where uncertainty is balanced by certainties or generates certainties.47

5.3 Pragmatic principle

5.3.1 Nursing literature

Time is described as an influencing factor of self-organization15, 17, 40 since the ability to adapt40 to a new way of being15 passes several stages.17

However, self-organization in individuals with cancer is accelerated as soon as therapy was completed and they experienced fewer therapy-related side effects and thought less about their disease.35 Self-organization in individuals with progressive diseases increasingly deteriorating over time is accelerated as well, because the present time of affected individuals is perceived as limited, thereby intensifying the transition.15

Self-organization in chronic illness is characterized by the reconsideration of values, priorities, goals in life,17, 40 and commitments.33 Self-organizing individuals pursue the goal to conserve energy, to live as normally as possible and to create new and positive health behaviors.17 Furthermore, self-organizing individuals do not take anything for granted anymore.15, 35

The process of self-organization results in the reorganization of life.6 This outcome is described as a new sense of order in individuals with chronic pain and spiritual imbalance through traumatic life events,10, 54 as extended consciousness52 and a broadened vision.40 These outcomes reflect psychological adjustment equated with growth through uncertainty.6 Thereby, self-organizing individuals are moving from hopelessness to optimism.33, 40 They develop flexibility6, 17 and an enhanced appreciation for life.17, 35 Furthermore, self-organization results in increased perception of opportunities, quality of life,6 confidence and courage,35 a new sense of control,10, 39 less sensitivity to social pressures,15 the development of new resources, and new roles in daily life and society.37 Finally, self-organization results in an improvement of finding solutions for uncertain situations.52

In the context of self-organization, we identified one assessment measuring growth through uncertainty in illness. The Growth through Uncertainty Scale55 measures growth and experienced changes in one's view of life due to uncertainty. The instrument addresses four latent constructs regarding a new view of life, acceptance of the situation, continuing uncertainty, and negative consequences.6

5.3.2 Literature of other health and social science disciplines

Self-organization is a latent concept in all human beings, as complex open systems and exists in far-from-equilibrium conditions. Systems self-organize to overcome a disrupted pattern.43

Parry47 (from the field of social work) claims that uncertainty can be a catalyst for self-organization leading to growth. According to the literature of other health and social science disciplines, the capacity of individuals for self-organization is closely related to resilience and intrinsic processes but also to the environment. These kinds of systems are open and connected with the environment, for example, by stimuli provoking a change in normality. In the identified literature concerning psychology, the environment influences the form of the self-organizing system since systems self-organize to cope with their environment.43 Self-organizing processes depend on external input, by physical and emotional relationships to others. Furthermore, self-organization is influenced by social support, such as assistance with information seeking and avoiding, giving acceptance or validation, allowing ventilation and encouraging perspective shifts.44, 56

Self-organizing systems are thriving.47 They develop and maintain their structure.43 Furthermore, they have to modify and evolve their structure continuously.57 Therefore, self-organization is characterized by internal feedback loops.56

Self-organizing processes are continuously allowing systems to become more ordered and more complex over time.57 Self-organized individuals live every day with more consciousness, thereby refocusing on relevant questions about life.44 Their outlook on life is oriented toward appreciating and enjoying life,47 described as “psychospiritual growth”, “resilience”, “optimism”,47 and “empowerment”.40 “Growth” in self-organized individuals manifests itself by being more positive,45, 47 hopeful,44, 45 faithful, and certain about one's own strength and resilience. Once self-organization is succeeded, individuals experiencing uncertainty no longer require active support.47

5.4 Linguistic principle

5.4.1 Nursing literature

The concept of self-organization in nursing literature is used interchangeably with “adaptation”,37, 40 “coping”,35 “transformation”,52 and “adjustment”.37 Most often it is explicitly or implicitly described as a transition,13, 15, 33-35, 40, 47 a development process leading from one state to another, for example from illness-related uncertainty to certainty,17, 34, 47 from one perspective of life to a new one,15 from vagueness to surety35 or from hopelessness to optimism.33, 40

In addition, self-organization shows many similarities with the concept of probabilistic thinking. This becomes particularly clear when considering the pragmatic principle of the concept implying that self-organization manifests itself through a changed way of thinking. However, so far in the literature no definitive boundaries or interrelationships were drawn between self-organization and the terms.

5.4.2 Literature of other health and social science disciplines

In the literature of other disciplines self-organization is also used synonymously with other terms. Skar43 (from the field of psychology) and Brashers et al.45 (from the field of communication science) defined self-organization as adaptation to changing conditions due to instability and resulting in new structures or modes of behavior.43 In social work, self-organization is defined as a transition from coping to transformational psychospiritual growth as well as from managing uncertainty to recognizing certainties.47 In the psychological literature, the boundaries of self-organization are described with a focus on external inputs in systems that are open and connected with the environment.43 However, dictionary entries emphasized the intrinsic nature of self-organization emerging without external influence.58, 59

5.5 Logical principle

5.5.1 Nursing literature

Self-organization in nursing is understood as a transition from appraising uncertainty as a danger to reappraising it as an opportunity. However, this includes only the antecedent state and the consequences of the concept, while the actual development process of self-organization is not covered by this understanding. Indications are provided by its outcomes, since self-organization results in a new view of life,6, 15, 17, 32, 33, 39, 54, 60 the incorporation of uncertainty into a broadened perspective,15, 33, 40 a changed sense of what is important in life, the restructuring of reality,17 and new meanings of normality.37

Still, we could not identify any explicit attributes of the “blackbox” between the antecedent state and the outcomes of self-organization. However, we found that implicit characteristics of self-organization overlap with the understanding of cognitive reframing—a concept with origins in the field of psychology. Cognitive reframing fits the logic of self-organization in the nursing literature as it focuses on the transformation of self-limiting or distressing cognitions into cognitions fostering adaptation and reducing anxiety, depression and stress.61, 62 In the context of nursing its defining attributes include “sense of personal control,” “altering or self-altering perceptions of negative, distorted, or self-defeating beliefs,” “converting a negative, self-destructive idea into a positive, supportive idea,” and “the goal for cognitive reframing is to change behavior and improve well-being”.42 According to the concept analysis of Robson and Troutman-Jordan,42 cognitive reframing can be defined as an altered perception of things and the attempt to perceive ideas, events or situations in a different way by changing the perspective.63 Cognitive reframing involves viewing the same situation in a different frame still fitting the context but changing the entire meaning. Thereby, one's appraisal of an experience is usually more positive.64

5.5.2 Literature of other health and social science disciplines

In other disciplines, the implicit meanings of self-organization show the same overlaps with cognitive reframing by focusing on the reevaluation of priorities, values and importance in life.41, 45, 47 It is furthermore characterized by a process of learning to be grateful47 and a by a new view of life.41, 44, 45, 47 Thereby, individuals appreciate life, its purpose47 and the impermanence of life situations more fully.45

5.6 Theoretical definition of self-organization

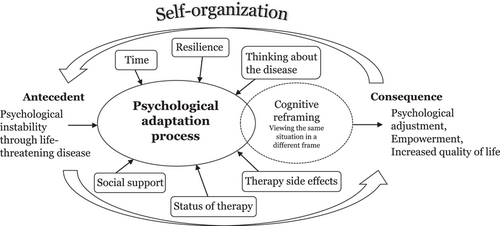

Self-organization stands for a transition between psychological instability and psychological adjustment. It is conditioned by illness-related obstacles or uncertainties that are perceived as life-threatening. Within this transition a latent psychological adaptation process takes place that shows overlaps with the concept of cognitive reframing, which is promoted by time, resilience, social support, and positive development of the disease. The consequence of psychological adjustment incorporates empowerment.

Antecedents, promoting factors, characteristics and consequences of self-organization are summarized in Table 1. Their relationships are shown as a theoretical model in Figure 2.

| Self-organization | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents | Promoting factors | Characteristics | Consequences |

| Psychological instability due to: | Time | Transition between psychological instability and psychological adjustment | Psychological adjustment, which is manifested by: |

| Progressive disease | Resilience | Psychological adaptation process | Extended consciousness |

| Increasing condition deterioration | Social support | Cognitive reframing | Increased confidence and courage |

| Hopelessness | Fewer therapy-related side effects | Latent | A new sense of control |

| Uncertainty | Therapy completion | Continuously evolving | Empowerment |

| Thinking less about the disease | Increased quality of life | ||

6 DISCUSSION

This principle-based concept analysis aims to theoretically define the concept of self-organization to support the understanding of how the uncertainty appraisal changes positively over time in individuals with a chronic disease. The findings shall subsequently contribute to increase understanding of the RUIT and thus its potential applicability.

Since Mishel has already stated that self-organization leads to a positive reappraisal of uncertainty in chronic illness,5 the results of this concept analysis show that authors, not just in the field of nursing, mostly replicated the outcome-focused knowledge of the concept in the recent years. However, hardly any new knowledge has been added to the RUIT at a lower level of abstraction about the actual reappraisal process within self-organization of chronic ill individuals. As a consequence the concrete meaning of self-organization originating from Chaos theory8 stayed blurred for the context of chronic illness. However, if a theory does not serve its purpose, this may be due to concepts not adequately reflecting the phenomenon.18 Davis and Sumara65 assign the concept of self-organization to complexity science. They argue that researchers from the social sciences working with the concept conduct “soft complexity science”65 since they try to represent interconnections of complex phenomena in a nonmathematical way by making use of “images and metaphors”.65 Sherblom56 claimed that social scientists using complexity language tend to apply metaphoric expressions and cause confusion about what really is meant. According to Sherblom, self-organization manifests itself in fundamentally different ways in a conscious individual than in systems, for example, in material sciences where the concept has its origins.8 Self-organization in a person is characterized by human awareness, self-directed action, the social influence of culture and time, as well as by personal challenges.56 Therefore, it should be distinguished from self-organization at the system level. Sherblom56 concludes that social scientists should attempt to adapt the concept to the social context in systems involving human consciousness.

The need to adapt the concept becomes especially clear when considering that middle range theories like the RUIT should be less abstract and narrower in scope.1 They should be described in more detail and should comprise more concrete concepts and their relationships.66 Therefore, it appears necessary to specify the concept of self-organization for the context of uncertainty in chronic illness.

As identified in this concept analysis, the understanding of cognitive reframing shows potential to understand the positive reappraisal of uncertainty in chronic illness more comprehensibly. Its psychological underpinning represents a first basic difference to self-organization, which could be useful to elaborate on the psychological adaptation process of self-organization. This may have emerged less in the literature because the original understanding of self-organization was unquestioningly taken from its original context, thereby missing the need to adapt it to the social and psychological context. Both concepts are conditioned by a negatively appraised antecedent state, are characterized by a change in perspective that results in a psychological adaptation process. However, cognitive reframing, especially in nursing is operationalized in more detail and allows deeper understanding of the actual adaptation process. Vernooij-Dassen et al.67 recommend the theoretical framework of symbolic interactionism to explain this underlying process. It implicates that the meaning someone ascribes to a situation is essential to understand how a person handles this situation. According to this framework, people are able to reflect on these attributions and to change them.68 This, in turn, can improve coping and quality of life, reduce burden, and mental morbidity.67

Nevertheless, how these two concepts ultimately relate to each other needs to be further explored to ultimately extend the RUIT and to strengthen the understanding of uncertainty in chronic illness.

7 CONCLUSIONS

With this principle-based concept analysis, we contributed to an enhanced understanding of the RUIT by developing across-disciplinary theoretical definition of self-organization and by proposing the psychological concept of cognitive reframing for the specification of self-organization in the RUIT. However, according to the understanding of Penrod and Hupcey concepts are like “knots in a tapestry”22 thus not independent of their theoretical context. Following, the redefinition of the concept will entail a change in the whole theory.18 The results of our concept analysis will therefore provide a basis for the future revision and extension of the RUIT to increase its potential applicability in research and practice. Nevertheless, the concept of cognitive reframing should first be explored more deeply in the context of uncertainty in chronic illnesses to confirm its relevance for the RUIT. Therefore, we recommend conducting qualitative longitudinal research to examine the missing links.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jasmin Eppel-Meichlinger: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and the analysis of data for the work; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Hanna Mayer: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; Revising the work critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Andrea Kobleder: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; Revising the work critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge support by Open Access Publishing Fund of Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Krems, Austria.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.