Clinical impact of rehabilitation and ICU diary on critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Abstract

Background

Various physical and mental sequelae reduce the quality of life (QOL) of intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Current guidelines recommend multi-angular approaches to prevent these sequelae. Some studies have demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of rehabilitation or the ICU diary against these sequelae, whereas others have not.

Aim

The aims of the present study were to establish whether rehabilitation or the ICU diary was useful for reducing the severity of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in ICU patients. We also investigated whether these interventions improved the QOL of these patients.

Study design

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of relevant randomized controlled trials published between January 1, 1985, and October 19, 2022, with the following search engines: PubMed, CHINAHL, all Ovid journals, and CENTRAL. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), the short-form health survey (SF-36), the EuroQol 5-dimensions, 5-levels (EQ-5D-5L), and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) were used as outcome measures. The quality of evidence across all studies was independently assessed using Review Manager software (v.5.4).

Results

We included 12 rehabilitation studies and five ICU diary studies. Rehabilitation had no significant effects on HADS-anxiety, HADS-depression, or EQ-5D-5L, but significantly improved the physical component summary (PCS) [MD = 3.31, 95%CI (1.33 to 5.28), p = .001] and mental component summary (MCS) [MD = 4.31, 95%CI: (1.48 to 7.14), p = .003] of the SF-36. The ICU diary significantly ameliorated HADS-anxiety [MD = 0.96, 95%CI: (0.21 to 1.71), p = .01], but did not affect HADS-depression, the IES-R, or the PCS or MCS of the SF-36.

Conclusions

The present study showed that rehabilitation initiated after discharge from the ICU effectively improved SF-36 scores. The ICU diary ameliorated HADS-anxiety. Neither rehabilitation nor the ICU diary attenuated HADS-depression or IES-R in this setting. Rehabilitation and the ICU diary partially improved the long-term prognosis of ICU patients.

Relevance to clinical practice

The present study provides evidence for the beneficial effects of rehabilitation and the ICU diary for ICU patients. Rehabilitation alone does not ameliorate anxiety, depression, or PTSD symptoms, but may improve QOL. The ICU diary only appeared to ameliorate anxiety.

What is known about the topic

- Physical and mental sequelae need to be managed in order to improve the QOL of patients and their families.

- A bundle approach to prevent physical and mental sequelae helps to achieve short ICU stays and is associated with hospital survival.

- The exact clinical effects of specific physical or mental interventions are ambiguous.

What this paper adds

- We showed that rehabilitation over a certain period of time effectively improved overall QOL. Rehabilitation alone does not ameliorate anxiety, depression, or PTSD symptoms, but may improve QOL.

- The ICU diary ameliorates HADS-anxiety, but may exacerbate PTSD. Therefore, it needs to be provided after an assessment of the risk of PTSD.

1 BACKGROUND

Various sequelae, such as physical weakness, impaired cognition, and mental disorders, are inevitable in critically ill patients.1 These symptoms are defined as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS),2 which persists even after discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU).1 Family members may also develop psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, acute stress disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 Therefore, PICS needs to be managed in order to improve the quality of life (QOL) of both patients and their families.

PICS includes ICU-acquired neuromuscular weakness, anxiety, depression, and PTSD, for example.4 Vasilevskis et al. showed that the bundle approach improved cognitive and functional outcomes in ICU patients and reduced mortality.5 Bundles consist of several interventions, such as the management of awareness and breathing, the choice of sedatives, daily delirium monitoring, early mobility, family engagement, good communication practices, and handout material provided by healthcare workers and their families.6 This approach helps to achieve not only short ICU stays, but also high hospital survival.7, 8 Therefore, current guidelines recommend bundled approaches consisting of awakening, breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, early exercise/mobility, and family engagement.9 The beneficial effects of bundle approaches on physical and cognitive sequelae were proven by reductions in deep sedation and immobilisation.10 However, their effects on mental sequelae warrant further study.

Although the bundle approach8 and ICU diary11 are important for critically ill patients to improve clinical outcomes and QOL, their exact clinical effects remain unclear, particularly for mental sequelae. Some studies showed that rehabilitation and the ICU diary improved the long-term QOL of critically ill patients,11, 12 whereas others did not.13, 14 Furthermore, the effects of rehabilitation on mental health15, 16 and the ICU diary on the recovery of patients and their families17 have not yet been elucidated. Therefore, to improve the QOL of critically ill patients, the effectiveness of these interventions needs to be clarified.

Various assessments to evaluate the clinical effects of rehabilitation and the ICU diary have been reported. The status of anxiety and depression is examined using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).18 The QOL of patients is measured using the short-form health survey (SF-36) and EuroQol 5-dimensions, 5-levels (EQ-51D-5L).19, 20 In addition, the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R) is used to assess the symptoms of PTSD.21

Previous studies used these questionnaires to quantitatively examine the effectiveness of rehabilitation or the ICU diary; however, the findings obtained were inconsistent. Therefore, we herein compare these assessments based on the findings of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on rehabilitation or the ICU diary for critically ill patients.

2 AIMS

The present study aimed to establish whether rehabilitation or the ICU diary was useful for reducing the severity of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in ICU patients. We also investigated whether these interventions improved the QOL of patients.

3 METHODS

3.1 Study design

We performed this systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) methodology.22 The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (#CRD42020198973). The present study was performed to demonstrate the clinical effects of rehabilitation or the ICU diary on ICU patients. The rehabilitation and ICU diaries examined in this study are described in Tables S1–S3.

We performed a comprehensive literature search of PubMed (Table S4), CHINAHL (Table S5), all Ovid journals (Table S6), and CENTRAL (Table S7) for relevant articles published between 1 January 1985, and 19 October 2022. Before the search was performed, the search protocol was augmented and assessed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines by an experienced librarian.23

Authors independently reviewed the title and abstract of each of the articles identified in the literature search to select potential articles. Regarding patients, populations, and issues, inclusion criteria were adults (older than 18 years) admitted to the ICU with critical illnesses whose cases were described in English-language publications or unpublished literature dated after 1 January 1985. Selected studies were limited to RCTs in order to ensure an appropriate level of evidence. Regarding interventions, the inclusion criterion was rehabilitation or the ICU diary for patients who had stayed in or were discharged from the ICU.

Exclusion criteria were duplicate studies or studies involving the same database or population and patients younger than 17 years. The full text and references of each article or abstract that passed the initial screening were analysed to identify any articles that had been missed. Specifically, the full text of each article selected during the initial screening and the references listed within them were read by each reviewer, and any relevant studies were selected according to the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The four abovementioned authors independently reviewed each article for final inclusion at the full-text screening stage, and group consensus was used to resolve conflicts.

3.2 Data collection and processing

Authors independently analysed each of the included studies to extract information, which was entered into an Excel spreadsheet. The information extracted from each article included a description of the research outline (title, first author, journal name, and the year of publication), the research design (purpose, research period, subject selection criteria and exclusion criteria, age, admitting diagnosis, severity, ICU stay period, total number of subjects recruited, and the total number of subjects analysed), the interventions performed (contents, treatments employed in the control group, period, and endpoints), and the study outcomes (results, sample size, and p-values). Group consensus was used to resolve any conflicts regarding the extracted data.

The abovementioned authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) guidance. We assessed random sequence generation, allocation concealment, the blinding of participants and personnel, the blinding of outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. We judged each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and justified our judgement. We used the EPOC risk of bias guidance to help reach our judgements. Other authors settled any disagreements between the independent authors. Publication bias was not evaluated because the number of studies in each subgroup was 10 or less.

3.3 Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the HADS score. The secondary outcomes included SF-36, EQ-5D-5L, and IES-R scores. HADS is a measurement scale for anxiety and depression that is widely used worldwide. It consists of 14 items, including seven items each for anxiety and depression, and each item is measured on a 4-point scale (range: 0–21).18 The SF-36 measures health-related QOL. It is used to produce a physical component summary (PCS, range: 0–100), which measures physical aspects, including physical function, physical role functioning, body pain, and general health, and a mental component summary (MCS, range: 0–100), which measures mental aspects, including vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health.19 The score for each domain ranges between 0 and 100, with an average of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10. The EQ-5D-5L measures QOL and is used to calculate quality-adjusted life-year values. It consists of five questions, each of which is measured on a 5-point scale, and, thus, may yield 3125 combinations of QOL scores (range: 0–1.0).20 The IES-R is a self-completed questionnaire that measures the severity of PTSD symptoms. It consists of 22 items, including eight related to intrusion symptoms, eight related to avoidance symptoms, and six related to hyperarousal symptoms, each of which is assessed using a 5-point scale (range: 0–88).21

We excluded the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory-II, PTSD Symptom Scale, WHO-QOL, and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy because of an insufficient number of outcomes.

3.4 Primary data analysis

The pooled effects of rehabilitation or the ICU diary were assessed using a random-effects model and the inverse-variance method. Mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Estimates of the mean and SD were calculated for data given as medians and interquartile ranges.24 Results are displayed graphically on forest plots. The observed heterogeneity for the summary and subgroup analyses was measured with the I2 statistic.25 Data synthesis and statistical analyses were performed with Review Manager (version 5.4; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Funnel plots were created and visually inspected to assess the presence/absence of publication bias.

3.5 Intervention

We analysed studies that provided rehabilitation or an ICU diary. Rehabilitation was defined as exercise, education, the provision of information, and psychosocial support.26 We focused on exercise, which involves muscular and physical activities to increase cardio-respiratory work and practices to improve performance.26 Rehabilitation programmes in the present study included the following: turning side-to-side on the bed, isometric and resistance exercises, sitting on the edge of the bed, moving from the bed to a chair, cycling ergometry, and walking (Tables S1 and S2). Because clinical outcomes are affected by the timing of the initiation of rehabilitation,27 we divided patients into subgroups that started rehabilitation during the ICU stay or after discharge from the ICU. The ICU diary is generally completed on behalf of patients to provide events recorded throughout their admission to the ICU (Table S3).28

4 RESULTS

4.1 Search results

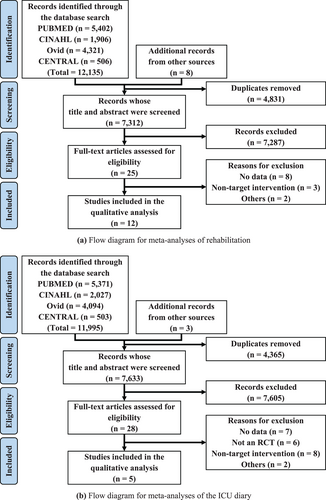

The PRISMA flow diagram for rehabilitation is shown in Figure 1. The database search for relevant studies on rehabilitation resulted in 12 135 studies being identified, with an additional eight studies. We excluded 4831 studies because of duplication, and the titles and abstracts of the remaining 7312 studies were screened. As a result, we excluded 7287 unrelated studies. We reviewed the remaining 25 full-text articles to further evaluate their eligibility. We excluded eight studies for which data were unavailable from the body or appendices,29-36 three in which interventions were not categorized as rehabilitation,37-39 and two were excluded for other reasons.40, 41 Therefore, we included 12 studies in our meta-analysis.12, 13, 42-51

The PRISMA flow diagram for the ICU diary is shown in Figure 1b. The database search for relevant studies on the ICU diary resulted in 11 995 studies being identified, with an additional three studies. We excluded 4365 studies because of duplication, and the titles and abstracts of the remaining 7633 studies were screened. As a result, we excluded 7605 unrelated studies. We reviewed the remaining 28 full-text articles to further evaluate their eligibility. We excluded 7 studies for which data were unavailable from the body or appendices,52-58 six that had non-RCT designs,59-64 eight in which interventions were not categorized as the ICU diary,65-72 and two were excluded for other reasons.73, 74 Therefore, we included five studies in our meta-analysis.14, 75-78

4.2 Study characteristics

The demographics of the populations in rehabilitation studies are shown in Table 1,12, 13, 42-51 and those of the populations in ICU diary studies are shown in Table 2.14, 75-78 Details on rehabilitation programmes and the ICU diary are shown in Tables S2 and S3. The follow-up period lasted ≤12 months in all studies.

| Author | Year | Timing of starting rehabilitation | SC (n) | HADS-A | HADS-D | SF-36 PCS | SF-36 MCS | EQ-5D-5L | Follow | ITT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rehab (n) | ||||||||||

| Hodgson | 201642 | During ICU stay | 16 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.63±0.33 | 6 M | No |

| 21 | 0.63±0.27 | |||||||||

| Morris | 201643 | During ICU stay | 81 | ND | ND | 33.5±11.2 | 46.4±11.6 | ND | 6 M | Yes |

| 84 | 36.9±10.9 | 48.8±11.4 | ||||||||

| Wright | 201844 | During ICU stay | 158 | ND | ND | 34.0±9.0 | 45.0±12.3 | 0.45±0.32 | 3 M | No |

| 150 | 35.0±10.8 | 47.0±11.8 | 0.51±0.35 | |||||||

| Hojskov | 201945 | During ICU stay | 310 | 4.3±3.7 | 4.3±3.7 | ND | ND | ND | 4 W | No |

| 310 | 3.5±3.4 | 3.7±3.2 | ||||||||

| Batterham | 201413 | Discharge from the ICU | 25 | 7.0±3.8 | 4.8±3.1 | 46.6±10.5 | 46.6±11.7 | 0.71±0.23 | 26 W | No |

| 21 | 6.3±3.8 | 4.0±3.1 | 46.7±10.5 | 51.0±11.7 | 0.67±0.23 | |||||

| Connolly | 201546 | Discharge from the ICU | 6 | 3.6±5.0 | 4.2±5.7 | 39.3±18.8 | 44.9±19.5 | ND | 3 M | No |

| 10 | 3.8±3.2 | 4.3±5.4 | 34.1±18.6 | 50.6±16.6 | ||||||

| McDowell | 201647 | Discharge from the ICU | 28 | 6.9±3.3 | 5.5±3.1 | 37.2±6.7 | 46.1±13.1 | 0.62±0.37 | 6 W | No |

| 22 | 9.9±3.6 | 7.5±3.6 | 40.0±7.8 | 43.8±13.6 | 0.52±0.50 | |||||

| McWilliams | 201648 | Discharge from the ICU | 33 | ND | ND | 36.1±9.2 | 41.3±10.6 | ND | 16 W | No |

| 30 | 39.6±9.1 | 48.6±11.2 | ||||||||

| Vitacca | 201649 | Discharge from the ICU | 15 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.23±0.90 | 6 M | No |

| 21 | 0.03±0.46 | |||||||||

| Shelly | 201712 | Discharge from the ICU | 16 | ND | ND | 36.4±3.9 | 45.0±7.1 | ND | 4 W | No |

| 12 | 41.3±5.4 | 50.5±7.3 | ||||||||

| Battle | 201850 | Discharge from the ICU | 19 | 8.6±4.1 | 7.6±4.7 | ND | ND | ND | 12 M | No |

| 15 | 3.7±3.0 | 4.0±3.8 | ||||||||

| Veldema | 201951 | Discharge from the ICU | 14 | ND | ND | 27.8±6.6 | 49.4±11.9 | ND | 4 W | Yes |

| 13 | 31.1±9.1 | 51.9±12.8 |

- Abbreviations: -A, anxiety; -D, depression; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5-dimensions, 5-levels; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ITT, intention to treat; MCS, mental component summary; ND, not described; PCS, physical component summary; Rehab, rehabilitation;SC, standard care; SF, Short-Form Health Survey.

| Author | Year | SC (n) | HADS-A | HADS-D | IES-R | Follow | ITT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diary (n) | |||||||

| Knowles | 200975 | 18 | 6.6 ± 4.5 | 8.3 ± 5.1 | ND | 6 W | Yes |

| 18 | 4.7 ± 3.0 | 4.2 ± 3.0 | |||||

| Kredentser | 201876 | 6 | 7.5 ± 2.9 | 4.5 ± 4.8 | 19.8 ± 27.3 | 3M | No |

| 13 | 4.0 ± 4.2 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 13.3 ± 11.0 | ||||

| Garrouste-Orgeas | 201977 | 175 | 5.3 ± 4.5 | 4.0 ± 3.7 | 15.3 ± 15.7 | 3M | No |

| 164 | 5.0 ± 4.5 | 4.0 ± 4.5 | 14.0 ± 15.0 | ||||

| Castillo | 202078 | 8 | 5.8 ± 5.8 | 4.5 ± 5.8 | ND | 6M | No |

| 16 | 3.8 ± 3.3 | 3.8 ± 3.9 | |||||

| Wang | 202014 | 49 | 4.0 ± 2.6 | 3.1 ± 2.9 | 25.2 ± 13.0 | 1M | No |

| 46 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 2.5 | 20.7 ± 12.1 |

- Abbreviations: -A, anxiety; -D, depression; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES-R, Impact of Event Scale-Revised; ITT, intention-to-treat; ND, not described;SC, standard care.

A summary of the risk of bias in each study is shown in Figure S1 and a graph of the risk of bias in Figure S1. The randomization methods employed in two studies were unknown.49, 50 The blinding of subjects and researchers was categorized as high risk for all studies because of the nature of the study protocols. Only three studies were categorized as low risk for incomplete outcome data because of drop-outs associated with critical illness.43, 51, 75

4.3 Meta-analysis findings

A forest plot of HADS scores comparing standard care (SC) with rehabilitation is shown in Figure S1. HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression scores did not significantly differ between the SC and rehabilitation groups. The funnel plots of HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression for the rehabilitation studies exhibited asymmetric configurations (Figure S1).

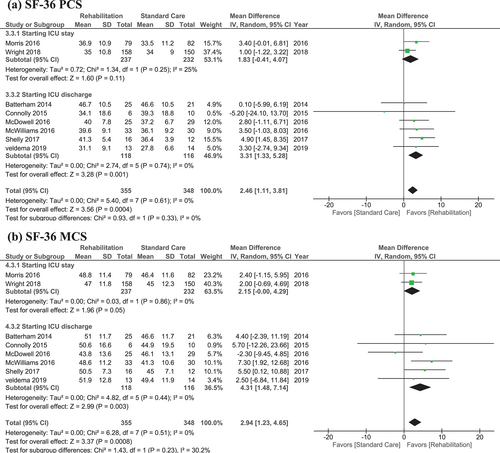

A forest plot of SF-36 scores comparing SC with rehabilitation is shown in Figure 2. Significant differences in SF-36 PCS [MD = 2.46, 95%CI: (1.11 to 3.81), p = 0.0004: Figure 2a] and MCS scores [MD = 2.94, 95%CI: (1.23 to 4.65), p = 0.0008: Figure 2b] were detected between the SC and rehabilitation groups. Rehabilitation that started during the patient's ICU stay did not have any significant effect on the PCS or MCS score. On the other hand, rehabilitation that started after the patient was discharged from the ICU led to significant improvements in PCS [MD = 3.31, 95%CI: (1.33 to 5.28), p = 0.001: Figure 2a] and MCS [MD = 4.31, 95%CI: (1.48 to 7.14), p = 0.003: Figure 2b] scores. Funnel plots of SF-36 PCS and MCS scores for rehabilitation studies exhibited asymmetric configurations (Figure S1).

A forest plot of EQ-5D-5L scores comparing SC with rehabilitation is shown in Figure S1. The mean EQ-5D-5L score did not significantly differ between the SC and rehabilitation groups. The funnel plot of EQ-5D-5L scores exhibited an asymmetric configuration (Figure S1).

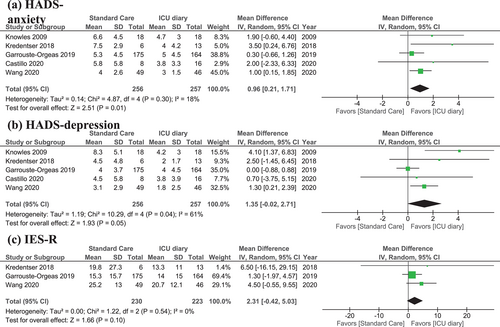

A forest plot of HADS scores comparing SC with the ICU diary is shown in Figures 3a,b. The mean HADS-anxiety score significantly differed between the SC and ICU diary groups [MD = 0.96, 95%CI: (0.21 to 1.71), p = 0.01: Figure 3a], whereas the mean HADS-depression score did not. The funnel plots of HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression for ICU diary studies exhibited asymmetric configurations (Figure S1).

A forest plot of IES-R scores comparing SC with the ICU diary is shown in Figure 3c. The mean IES-R score did not significantly differ between the SC and ICU diary groups. The funnel plot of IES-R scores exhibited an asymmetric configuration (Figure S1).

5 DISCUSSION

The present study showed that rehabilitation improved the SF-36 scores of critically ill patients, and the ICU diary ameliorated HADS-anxiety. However, neither rehabilitation nor the ICU diary attenuated HADS-depression or IES-R. Furthermore, rehabilitation did not improve the EQ-5D-5L scores of ICU patients.

5.1 Anxiety and depression

Rehabilitation did not ameliorate anxiety or depression in ICU patients. Rehabilitation is designed to maintain or improve physical functions. Exercise alone cannot improve psychosocial health unless additional interventions involving either psychosocial or educational programmes are provided.47 Therefore, additional specific methods other than exercise need to be considered in order to ameliorate anxiety or depression in patients.

The ICU diary effectively ameliorated anxiety, which is consistent with previous findings.76 The ICU diary helped critically ill patients reinforce their factual memory and distinguish between hallucinations and delusions.14 Therefore, it is an effective tool for reducing anxiety in ICU patients. On the other hand, the present results showed that the current ICU diary did not ameliorate depression in ICU patients. Depression differs from anxiety because of the lack of positive affect, temporal orientation, rhythmicity, rumination, and disinvestment in the self.79 This psychological gap may be the reason for the difference in the clinical effectiveness of the ICU diary against anxiety and depression. The ICU diary is helpful for organizing memories to reduce anxiety, but not for ameliorating depression.

5.2 PTSD

The ICU diary did not effectively improve the IES-R scores of critically ill patients; it is intended to prevent PTSD. PTSD symptoms are negative flashbacks, nightmares, and the avoidance of external reminders.80 The memories recalled by patients using the ICU diary may be negative flashbacks; nevertheless, they may improve anxiety. Because avoidance is a major symptom of PTSD, patients may avoid using the ICU diary to prevent being reminded of traumatic memories.75 Therefore, another programme needs to be developed that supports PTSD patients with mental issues. The ICU diary may ameliorate anxiety in critically ill patients.

5.3 QOL according to the SF-36

Rehabilitation significantly improved the SF-36 scores of ICU patients. It improved both PCS and MCS. Shelly et al. suggested that exercises increase the release of endorphins, promote circulation, and improve reactivity to stress.12 In addition, the physical functional status covaries with multiple mental health-related variables.81 A previous study reported a moderate to strong correlation between PCS and MCS.82 In terms of the SF-36, rehabilitation may improve patients' MCS scores through synergistic effects.

The present results showed that the initiation of rehabilitation during the ICU stay did not significantly affect the SF-36 PCS or MCS scores of ICU patients. On the other hand, rehabilitation effectively improved QOL when it was initiated after the patient was discharged from the ICU. A potential reason for the lack of effect of early rehabilitation initiated during the ICU stay is that an acute inflammatory response suppressed physical responses and muscle rearrangement under critical conditions.83 These scores are also affected by decreased daily activity levels and a worse nutritional status. Because the condition of critically ill patients may rapidly change, the provision of rehabilitation at an appropriate intensity and time is important, and it also needs to be personalized for inflammatory conditions.12, 84 The present study shows the need for rehabilitation programmes tailored to each patient's condition.

The minimum mean ± SD of the MCS score in the present study was 41.3 ± 10.6, while the maximum score was 51.9 ± 12.8.48, 51 This range may be too narrow to allow any effects of the interventions to be proven. The SF-36 MCS score ranges between 0 and 100. A detection bias needs to be considered when we deal with patient reported outcome (PRO). Patients who stay in the ICU often have difficulty responding to PRO on their own because of disease or medication. In these cases, the nurse has to read the questionnaire and respond on behalf of patients. As a result, the time to complete the questionnaires increases to 15–20 min, even though it typically takes only 5 minutes. A detection bias may arise on the SF-36 because of the large number of questions when it is used for critically ill patients. The timing of use of the SF-36 needs to be considered; however, it is a robust tool that is recommended to assess the QOL of critically ill patients.

5.4 QOL according to the EQ-5D-5L

The EQ-5D-5L was not adequate for examining the effects of rehabilitation, even though it is useful for evaluating QOL in the general population. There are several explanations for why the EQ-5D-5L score did not appear to be useful for the purposes of this study. Because it focuses on physical indicators,21 it may be unsuitable for measuring QOL in critically ill patients. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the EQ-5D-5L in critically ill patients may not be sufficient because of the ceiling effects of the utility score.85 Therefore, it was challenging to detect any effect of the examined support programmes using the EQ-5D-5L. The EQ-5D-5L may be unsuitable for evaluating the QOL of critically ill patients because of its nature and low sensitivity. Specific QOL evaluation tools need to be established for critically ill patients in the future.

6 LIMITATIONS

The present study was affected by several sources of bias. It was impossible to blind patients and caregivers to the type of support provided, which contributed to an execution bias. An evaluation bias was also inevitable because patients evaluated their own outcomes. This is expected for patient-reported outcomes, even though patients in the present study were not aware of whether standard or supportive care was administered. It was difficult to conduct an ITT analysis because of a dropout bias. Critically ill patients in the ICU are at risk of dying and may not survive to the primary endpoint. Only three out of the 20 studies involved ITT analyses.43, 51, 75 In addition, a detection bias may affect results because critically ill patients had difficulty answering the questionnaires by themselves.

The clinical effects of support programmes may vary because of differences in timing, duration, location, and interventions. In addition, patients constituted a heterogeneous population in which disease severity, aetiology, and the medical management strategies employed during recovery varied. All these issues need to be reconsidered before any final conclusions are reached.

7 RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The psychological sequelae of critically ill patients are a long-term concern. The results of the present study provide evidence for the effectiveness of rehabilitation and the ICU diary for mental sequelae. Patient-oriented rehabilitation alone does not directly address anxiety, depression, or PTSD, but improves mental aspects of QOL. The ICU diary may worsen PTSD in some patients under specific conditions, even though it ameliorates anxiety. Therefore, careful consideration is needed prior to the use of the ICU diary for critically ill patients.

8 CONCLUSION

The present results suggest that performing rehabilitation over a certain period of time effectively improves overall QOL. The ICU diary may ameliorate HADS-anxiety. Neither rehabilitation nor the ICU diary attenuated HADS-depression or IES-R in this setting. Rehabilitation and the ICU diary slightly improved the long-term prognosis of ICU patients. Further trials are needed to identify effective interventions and their timing in order to improve the QOL of critically ill patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Tomas H. Hui, Sandy Tan, and Miyako Nara for their valuable discussions and help in preparing this manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid from JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP 21K10715 to T. I. and JP 20K10404 to T. M.); the Yasuda Medical Foundation (Osaka, Japan. to T. I.); the Hokkaido Hepatitis B Litigation Orange Fund (Sapporo, Japan. to T. M.); Terumo Life Science Foundation (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Pfizer Health Research Foundation (Tokyo, Japan. to T.M.); the Viral Hepatitis Research Foundation of Japan (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Project Mirai Cancer Research Grants (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Takahashi Industrial and Economic Research Foundation (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Daiichi Sankyo Company (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Shionogi and Co. (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); MSD (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Takeda (Tokyo, Japan. to T. M.); Sapporo Doto Hospital (Sapporo, Japan. to T. M.); Noguchi Hospital (Otaru, Japan. to T. M.); Doki-kai Tomakomai Hospital (Tomakomai, Japan. to T. M.); and Tsuchida Hospital (Sapporo, Japan. to T. M.).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

The used data will not contain individual patient data; therefore, there are no concerns about patients' privacy.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Not applicable because this study is a meta-analysis.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

We permit to reproduce material from other sources.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (#CRD42020198973).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data in this meta-analysis were Referred from previously published papers. The analysed data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.