The influence of spirituality and religion on critical care nursing: An integrative review

Abstract

Background

Spiritual care could help family members and critically ill patients to cope with anxiety, stress and depression. However, health care professionals are poorly prepared and health managers are not allocating all the resources needed.

Aims and objectives

To critically review the empirical evidence concerning the influence of spirituality and religion (S-R) on critical care nursing.

Methods

An integrative review of the literature published in the last 10 years (2010-2019) was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, CINHAL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane and LILACS. In addition, searches were performed in the System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe and the Grey Literature Report. Quantitative and/or qualitative studies, assessing S-R and including health care professionals caring for critically ill patients (i.e. adults or children), were included.

Results

Forty articles were included in the final analysis (20 qualitative, 19 quantitative and 1 with a mixed methodology). The studies embraced the following themes: S-R importance and the use of coping among critical care patients and families; spiritual needs of patients and families; health care professionals' awareness of spiritual needs; ways to address spiritual care in the intensive care unit (ICU); definition of S-R by health care professionals; perceptions and barriers of addressing spiritual needs; and influence of S-R on health care professionals' outcomes and decisions. Our results indicate that patients and their families use S-R coping strategies to alleviate stressful situations in the ICU and that respecting patients' spiritual beliefs is an essential component of critical care. Although nurses consider spiritual care to be very important, they do not feel prepared to address S-R and report lack of time as the main barrier.

Conclusion and implications for practice

Critical care professionals should be aware about the needs of their patients and should be trained to handle S-R in clinical practice. Nurses are encouraged to increase their knowledge and awareness towards spiritual issues.

What is known about this topic

- Considering S-R needs and providing spiritual care is an important part of a holistic care for critically ill patients and should be considered by nurses. Studies have shown that S-R training could enhance the awareness and identification of S-R needs of the patients and family members, as well as could help improving the care of the patient.

What this paper adds

- This integrative review has shown that, although S-R needs are very common in the ICU environment, health care professionals are still little prepared to address these issues. From a research perspective, there are few studies and little empirical evidence of the influence of S-R on critical care nursing as well. Our results could stimulate future training concerning this topic and make these professionals more aware of this component of care.

1 INTRODUCTION

Spirituality and religiosity (S-R) have been discussed in health care for years and research in this area has been constantly growing and consolidating.1 Religion is defined as “the set of beliefs, practices, rituals and ceremonies that are normally acquired by tradition within a group or community.”2 On the other hand, spirituality is a broader concept, defined as “the personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life, about meaning and about relationship to the sacred or transcendent, which may (or may not) lead to or arise from the development of religious rituals and the formation of community.”2 Although these are clearly overlapping concepts, they could have different implications. However, it is important to consider that there is no consensus on the definition of S-R3 and a great number of authors use these terms as synonyms.

Another important observation while investigating this field of knowledge is the fact that cultural backgrounds have an important influence on the relationship between S-R and health care. Population from European countries (e.g. Sweden, Denmark) are usually more secular and S-R tend to be less incorporated in health care, whereas population from Asiatic and Middle East cultural backgrounds are more open to this issue and tend to include it more frequently in health care.4-6

In clinical practice, there has been increased consideration and recognition of S-R as part of the holistic model of care. Recent studies have shown that most patients want to discuss S-R with health care professionals in a routine basis, and indeed this willingness increases at the time of crisis.7, 8 Likewise, S-R can promote a better mental and physical health.9 Other findings show that individuals use S-R beliefs to cope and accept their illnesses and that spiritual care is an important factor in improving patients' quality of life during end-of-life care.10 However, Badanta et al11 found that S-R has a negative effect in terms of treatment adherence for patients with HIV and chronic conditions.

Within the critical care context, S-R needs of patients seem to increase when experiencing high levels of anxiety, stress and depression.12 However, studies concerning critically ill patients are relatively scarce, both in the intensive care units (ICUs), but also in other environments (e.g. emergency rooms) where these patients are becoming more common.13

In the context of critical care, life-threatening situations and unexpected changes are common, causing loss of hope and great anguish to the adult or child patient, family members and health care professional.3, 14 Although paediatric is different from adult critical care in several aspects, they share similarities such as the suffering of the family, the burn out levels of the critical care team, the stressful environment, and the end-of-life care.15

In the context of critical, understanding factors such as S-R beliefs that might influence health outcomes in care patients (adults or children) are needed. Previous studies revealed that spiritual care could help both patients and their families to cope better with the intensive care situation, generating beneficial effects for both patients and their family.16 Likewise, family members tend to use positive and negative coping strategies* during their relatives' hospitalization in the ICU, seeking support in spirituality and religious beliefs, such as hoping that God would resolve and control the situation.12

Despite the importance of S-R for critically ill patients and their families, ICU health care professionals recognize that they do not have appropriate resources to deal with spiritual care.16, 17 In a recent research on S-R in the intensive care setting carried out in United States, four basic recommendations for ICU patients concerning spiritual care were proposed: evaluation and incorporation of spiritual needs in the ICU care plan; training in spiritual care for doctors and nurses; medical review of interdisciplinary assessments of spiritual needs; and attention to patients' requests to pray with them.18 Therefore, paying attention to this dimension is essential to provide quality holistic care to patients, particularly in the ICU environment.

Although there are recent reviews concerning this topic, they were based on narrative reviews17 or clinical practice guidelines18 and not relying on a systematic approach. Another integrative review did not include other critical care patients (such as paediatric critical care patients), had limited the language of the studies (English, Dutch) and had included opinion articles.16 Our review has a different approach, aiming to include a comprehensive update of this field of research, not restricting the language of the studies, assessing the quality of these studies and including original research, both quantitative and qualitative, providing a panorama of the current evidence.

2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF REVIEW/REVIEW QUESTIONS

What are the needs and experiences of critically ill patients and their families towards S-R, and what kind of nursing care is provided to them?

What are the perceptions, knowledge, experiences and attitudes of nurses towards S-R care for critically ill patients and their families?

3 DESIGN AND METHODS

3.1 Search strategy

An integrative review was conducted between May and October 2019. First, we discussed the most appropriate methodology and developed a protocol based on Whittemore et al19 guidelines for integrative reviews. It was decided that the eligibility criteria, search strategies, data extraction, data synthesis and quality assessment would be predefined in order to reduce the possibility of a researcher bias. Whittemore et al19 identify five stages in conducting an integrative review: (a) Problem identification; (b) Literature search; (c) Data evaluation; (d) Data analysis and; (e) Presentation. A brief version of these guidelines adapted to our review can be visualized in Table S1.

Three reviewers (Reviewer 1, Reviewer 2 and Reviewer 4) carried out stage 1 (problem identification) from a theoretical perspective in order to provide focus and boundaries for the integrative review. Then, two reviewers (Reviewer 1 and Reviewer 2) independently carried out the literature search on seven electronic databases in the last 10 years: PubMed, Scopus, CINHAL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane and LILACS. We also looked at the reference lists of the included papers we may have missed. The keywords and Boolean expressions used for the search were combined as follows: (religio* OR “religious beliefs” OR spiritual* OR “spiritual care”) AND (“critical care” OR “intensive care” OR ICU) AND (nurs*).

In addition, one author (Author 3) conducted a search in the grey literature, which consists of any scientific material not gathered by conventional databases, such as doctoral theses and scientific communications. Searches were performed in the System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (OpenGrey) and the Grey Literature Report. The proceedings of national and international conferences held over the past 5 years by scientific societies related to this topic were also consulted. The grey literature search was intended to find valid articles cited by the authors of the reports, but finally, they did not strictly match our search parameters and did not provide valuable context for the integrative review. All retrieved references were entered in Mendeley software (version 1.19.4) to create and organize a bibliography of all the references we have cited.

3.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for selected articles

Articles were included if they investigated spiritual care in critically ill patients and their families and were: (a) peer-reviewed articles with original data published in the last 10 years, (b) quantitative, qualitative or mixed studies, and (c) met the PICOTS criteria (Table 1). In addition, no language limit was set.

| PICOTS criteria | |

|---|---|

| Population | Health care provider, patients and families in intensive care units (ICUs)/neonatal and paediatric intensive care units (NICU/PICU) |

| Intervention/exposure | Spiritual and/or religious |

| Comparator | Not applicable |

| Outcome | Spiritual care in patients treated in intensive and critical care services and their families |

| Time | Published in the last 10 years |

| Study design | Quantitative, qualitative studies and mixed methods |

This integrative literature review excluded any opinion pieces, such as editorials or other forms of popular media. In addition, studies where spirituality is addressed by a non-health care provider or a non-nursing care provider were also excluded, as well as those in which patients were not critically ill/did not receive critical care. Studies aiming to evaluate a specific S-R measurement tool were also excluded.

3.3 Study selection

The screening procedure was carried out by two reviewers (Reviewer 1 and Reviewer 2) independently in order to identify relevant studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. First, duplicate publications were removed and then the reviewers were screened by title and abstract. If there was a disagreement, another reviewer (Reviewer 4) was consulted.

Then, full text articles were screened by three reviewers (Reviewer 1, Reviewer 2 and Reviewer 4) who evaluated the general information in order to include only those studies that analysed S-R care in both adults and children critically ill patients. Any discrepancies in this process were solved by a fourth investigator (Reviewer 3).

3.4 Data extraction

One reviewer (Reviewer 1) was in charge of extracting and analysed the data from the papers, which was subsequently verified by another reviewer (Reviewer 3). Once the data had been extracted, a table was drawn up including authors, year, country, purpose of the study, research design, sample characteristics, data collection, instruments, and a summary of the major findings. The summary tables were thoroughly reviewed by three reviewers (Reviewer 1, Reviewer 3 and Reviewer 4) independently, with critical discussions of the extracted data.

3.5 Assessment of methodological quality

The studies that met the inclusion criteria were assessed by two reviewers independently for methodological validity prior to inclusion in the review (Author 1 and Author 4). Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer (Reviewer 3). The methodological quality was assessed using tools that ensure high-quality presentation of observational studies (i.e. STROBE),20clinical trials (i.e. CONSORT) 21 and of qualitative studies (i.e. SRQR guidelines) 22 in order to determinate a sound methodology within the retrieved studies. Studies scoring low on the appraisals would be excluded. For the SRQR, despite the fact that this score does not rate items, the following categorization was used based on the percentage of items meeting the appraisal criteria (Excellent: 80-100% of the items, Good: 50-80%, Regular: 30-50% and Poor: <30%).

3.6 Development of themes

In order to develop the themes for this integrative review, a thematic analysis approach was taken.23 The reviewers participating in the searches, screening, articles assessment and data extraction (Reviewer 1 and Reviewer 3) organized descriptive labels, focusing on emerging or persistent concepts and similarities or differences in S-R behaviours or practices, spirituality perceptions, and statements of nurses and family members. The coded data from each paper were examined and compared with the data from all the other studies. Finally, the different categories were gathered (grouped) into different themes.

4 RESULTS/FINDINGS

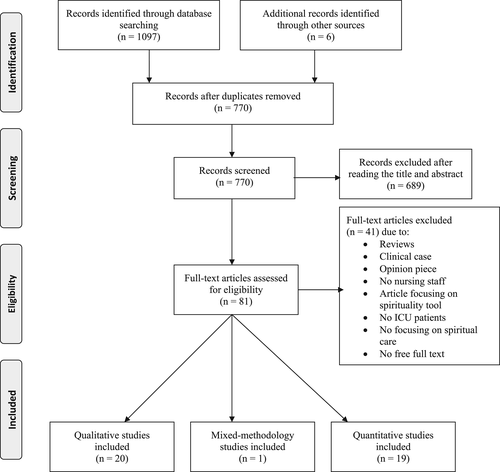

A total of 1097 articles were initially retrieved from the databases and 6 articles were identified via secondary searches from other sources, such as reference lists of the articles that met the inclusion criteria. The grey literature search did not result in any additional papers. After duplicates were removed, two reviewers independently (Reviewer 1 and Reviewer 2) examined the titles and abstracts of 770 records, seeking the adequacy of the subject for full text screening. Among them, 689 papers were excluded, obtaining a first sample of 81 records. Then, three reviewers (Reviewer 1, Reviewer 2 and Reviewer 4) continued the full text screening of the articles. Forty papers met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1), 34 from research databases and 6 from the manual search. All included articles were available in English language journals.

4.1 Characteristics and quality appraisal of the included studies

A total of 40 papers were included in the integrative review (20 had qualitative designs, 19 quantitative and 1 with mixed methodology). The quantitative studies were predominantly cross-sectional or descriptive studies (17 studies); but there were also two experimental studies (one randomized and one non-randomized clinical trials). All qualitative studies were characterized by the use of interviews, except one, which also incorporated a focus group technique as data collection methods. All included papers are presented in Table 2.

| References, Country | Purpose of the study | Research design and sample characteristics | Data collection and instruments | Major findings | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu-El-Noor,43 Palestine | To explore how Palestinian ICU nurses understand spirituality and the provision of spiritual care at the end of life | Qualitative study (interpretive-descriptive approach) (n = 13 ICU nurses) | Semi-structured interviews | Spirituality and spiritual care were very difficult to define for the ICU nurses and most of them made it in the context of religion. The majority of ICU nurses offered spiritual attention, especially when they felt that the treatment was useless and did not improve the condition of the patients, changing the goal of healing for being more attentive to the psychological and spiritual needs of others patients and their families | SRQR Excellent |

| Alimohammadi et al,33 Iran | To explore the clinical care needs of patients in the ICU with severe traumatic brain injuries (TBI), based on the nurses' perspectives | Qualitative study Purposive sampling (n = 14 ICU nurses) |

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews | The nurses considered paying attention to the religious beliefs and considering the patients as human beings and respecting the patients and their privacy as part of spiritual needs. They also expressed that providing spiritual care is one of the factors of patients' mental and physical comfort | SRQR Excellent |

| Al-Mutair et al,30 Saudi Arabia | To identify the perceived needs of Saudi families of patients in Intensive Care in relation to their culture and religion | Qualitative, exploratory study Purposive sampling (n = 12 family members) |

Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Saudi families have cultural and spiritual healing beliefs and practices including faith in God and that God is the ultimate healer, reading of the Qur'an, prayer, Shahadatain before the commencement of intubation and charity. These lessen their stress and connect them to hold on to hope In addition, maintaining proximity to their ill family member was considered of the greatest importance to the families |

SRQR Excellent |

| Al-Mutair et al,38 Saudi Arabia | To identify the needs of ICU patients' families in Saudi Arabia as perceived by family members and ICU health care providers | Quantitative, cross-sectional design Convenience sampling (n = 673, 176 family members and 497 intensive health care providers) |

Critical Care Family Need Inventory (CCFNI) | According to the cultural and spiritual needs, having the health care providers handle the body of the dead Muslim with extreme caution and respect, was perceived as the most important need by family members and the fifth most important need by the health care providers | STROBE 17/22 |

| Al-Mutair et al,36 Saudi Arabia | To explore the perceived impact and influence of cultural diversity on how neonatal and paediatric intensive care nurses (NICU/PICU) care for Muslim families before and after the death of children | Qualitative descriptive study Convenience sampling (n = 13 NICU/PICU nurses) |

Semi-structured interviews | Nurses described that the practices preferred by Muslim families when the baby/child was seriously ill or near the end of life were knowing that a copy of the Koran or an audio recording of the Koran was used for the dying baby/child, the use of Zamzam water (holy water recovered from the well of Zamzam in Mecca) and Muslim rituals regarding the orientation of the body looking at Mecca once the baby has passed away or securing his hands for prayer | SRQR/Good |

| Azarsa et al,14 Iran | To evaluate spiritual well-being, attitude toward spiritual care and its relationship with the spiritual care competence among ICUs nurses | Quantitative, correlational, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 109 ICU nurses) | Spiritual Well-being Scale, Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS) and Spiritual Care Competence Scale (SCCS) | The nurses' attitude towards spirituality and spiritual care influences the provision of spiritual care. The mean score of the spiritual well-being was 94.45, the spiritual care perspective was 58.77, and the spiritual care competence was 98.5, meaning that there was a positive relationship between the spiritual care competence with spiritual well-being and the way of providing these cares | STROBE 18/22 |

| Bakir et al,3 Turkey | To determine the experiences and perceptions of Muslim ICUs nurses about spirituality and spiritual care | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 145 ICU nurses) | SSCRS | Among the nurses, 44.8% received spiritual care training and 64.1% provided spiritual care to their patients. About their spiritual care practices, 28.3% stated that they used the therapeutic touch on patients. Barriers to provide spiritual care to patients were the “insufficient number of nurses (47.6%), excessive workload (28.3%), and fatigue (24.1%). The nurses being knowledgeable with spirituality and spiritual care were found to have a significantly higher spiritual care perception” | STROBE 17/22 |

| Bone et al,40 Canada | To explore the effect of spiritual care on nurses and how nurses understand the role of spiritual care in the ICU | Qualitative descriptive study Purposive sampling (n = 25 ICU nurses) |

Semi-structured interviews |

Nurses often disclosed being unaware of when they were providing spiritual care, and they also described how the presence of a chaplain supported caring for dying patients. They feel a sense of relief after calling chaplains, knowing they will jointly help support the patient and the patient's family | SRQR Good |

| Brelsford et al,27 USA | To determine whether secular and religious coping strategies were related to family functioning in the NICU | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study Parents of preterm infants (admitted to the NICU) (n = 52) |

Brief COPE (secular coping), the Brief RCOPE (religious coping), and the Family Environment Scale | Greater use of negative religious coping strategies, like feeling abandoned or punished by God, was significantly related to higher levels of denial and lower levels of family cohesion |

STROBE 19/22 |

| Canfield et al,52 USA | To examine critical care nurses' definition of spirituality, their comfort in providing spiritual care to patients, and their perceived need for education in providing this care | Qualitative study (Phenomenological method) Purposive sampling (n = 30 ICU nurses) |

Interviews | The spirituality as a belief in a higher power, higher being, or God was described by 47% of nurses. They did not feel a person had to be religious to be spiritual; however, the majority of the nurses then referenced religion as a means to express spirituality 75% expressed some degree of comfort providing spiritual care to critically ill patients. However, they mentioned the need of formal classes in different religions, cultures, or spiritual values |

SRQR Excellent |

| Choi et al,34 USA | To determine how ICU clinicians address the religious and spiritual needs of patients and families | Quantitative, cross-sectional design n = 219 clinicians (63 physicians, 138 nurses and 18 Advance Practice Providers) |

Questionnaires ad hoc | Levels of religiosity and spirituality correlated with how clinicians view their responsibility in addressing religious and spiritual concerns of patients A majority of clinicians (79% of attending, 74% of fellows, 89% of nurses and 83% of APPs) expressed that it is their responsibility to address the religious/ spiritual needs of patients but in the practice, only 14% of attending, 3% of fellows, 26% of nurses, and 17% of APPs asked patients about these questions | STROBE 20/22 |

| de Brito et al,46 Brazil | To investigate the comprehension of nurses of concepts of spirituality and spiritual necessities of patients without therapeutics possibilities | Qualitative, exploratory study (n = 7 ICU nurses) |

Interviews | It is evidenced the binding between S-R. Nurses consider the verbal communication and non-verbal communication (a tear, having a Bible) as instruments that can be used in identifying spiritual needs in patients and their family | SRQR Good |

| Ehsani et al,53 Iran | To explore the viewpoints of nurses working in ICUs about the concept of spiritual well-being | Quantitative, cross-sectional study Random sample (n = 62 ICU nurses) |

Questionnaire about spiritual well-being ad hoc | Among nurses, 53.2% had a positive attitude towards spiritual health, 27.4% had a moderate to somewhat favourable attitude, and 19.3% had a negative attitude. There was a positive significant correlation between spiritual care, age and work experience | STROBE 16/22 |

| Ernecoff et al,59 USA | To determine the frequency and characteristics of treatments on religiosity/spirituality among health care professionals and surrogate decision makers during visits to the ICU |

Mixed design (quali-quanti) (n = 546 surrogate decision makers and 150 health care professionals) | 249 goals-of-care conversations in 13 ICUs | Religion or spirituality were very important for surrogate decision maker's life (77.6%) and this is demonstrated in how religiosity or spirituality was raised in 40 of the family meetings (16.1%) where the most common belief was that God is ultimately responsible for health and that the physician is his instrument to promote healing. To face the surrogates' spiritual statements, health care professionals mainly redirected the conversation to medical considerations and offered to involve hospital spiritual care providers | SRQR Good STROBE 18/ 22 |

| Ghaljaei et al,48 Iran | To explain the spiritual challenges experienced by nurses in neonatal end of life in the NICU | Qualitative content analysis method Purposive sampling (n = 24 NICU nurses) |

Semi-structured in-depth interviews | The spiritual challenges experienced by nurses include challenge of psychological/spiritual support of family and spiritual distress of the nurse. Most of the nurses stated that spiritual/religious beliefs of families are an important factor to calm the family, however, a number of nurses believed that if the families are allowed for such actions, then the treatment procedure of newborns would be disrupted | SRQR Excellent |

| Green,39 Australia | To describe how neonatal nurses manage the situation of medical futility when the parents are hoping for divine intervention and a miracle | Qualitative study (Phenomenological method) Purposive sampling (n = 24 NICU nurses). |

Self-completed questionnaire and semi-structured interviews | The nurses all knew that religion played an important role in the lives of many families in the NICU. However, they did not know how to respond to the mother's belief in a miracle despite a dismal prognosis for the baby. They understood that praying for a miracle was about hope and parents who expected a miracle were unlikely to be swayed by medical science. The nurses acknowledged that parents needed time to spend with their baby and to be able to hope for a positive outcome or divine intervention; however, whenever the baby was on a dying trajectory, the nurses experienced moral distress |

SRQR Good |

| Heidari et al,28 Iran | To determine the perception of Iranian nurses towards spirituality in NICUs | Qualitative study Purposive sampling (n = 9 NICU staff: 8 nurses and 1 physician) |

Semi-structured interviews | Most of the participants stated that spirituality leads to peace of mind and helps resolve their problems and they have recourse to God while doing routine daily activities. Recoursing to God and Ahl-al Bayt is considered as an appropriate approach to enhance spirituality | SRQR Good |

| Hlahatsi et al,31 South Africa | To determine if critically ill patients' needs were met in 11 intensive care units of four private hospitals in Gauteng | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional design (n = 112 family patients) | Questionnaire ad hoc | Only 46% of the patients indicated that their spiritual needs were met in the intensive care unit (related to doubts and questions, to be informed when their relative's condition changed or to have a place close to the ICU to be with him) and 21% said the spiritual need was not applicable to them | STROBE 14/22 |

| Ibrahim et al,55 Brunei | To explore the spiritual coping with stress among the nurses in the Emergency Department and Critical Care Services in Brunei Darussalam | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 113 nurses) | Spiritual Coping Questionnaire (SCQ) | Majority of nurses perceived spiritual stress coping as religious (46.9%), personal (30.1%) achieving inner peace or strength and having a positive attitude- and social (6.19%) such as gaining support or advice from others such as family or friends. Those who have been working more than 15 years were using significantly lower negative religious coping | STROBE 18/22 |

| Kim and Yeom,54 South Korea | To describe the relationship between spiritual well-being and burnout of ICU nurses |

Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 318 ICU nurses) | Questionnaire ad hoc and the Spiritual Well-Being Scale and Burnout Questionnaire | Burnout was negatively correlated with spiritual well-being (r = −0.48, P < .001). Higher levels of spiritual well-being were associated with lower levels of burnout |

STROBE 20/22 |

| Kim et al,42 USA | To explore ICU nurses' experiences with providing spiritual care to critical patients and their families, perceptions about chaplains and the duties best performed by chaplains, and suggestions to meet the spiritual needs of critically ill patients, their families, and the ICU staff | Qualitative study Purposive sampling (n = 31 ICU nurses) |

In-depth interviews (n = 19) and 2 focus groups (n = 5 and n = 7) |

Most nurses did not feel prepared to meet the spiritual needs of critical patients and their families, so they invited a member of the spiritual care department, emphasized the supportive role of the chaplain. Nurses felt that their own spiritual needs should be met in order to offer spiritually based nursing care among patients and their families | SRQR Good |

| Kisorio and Langley,29 South Africa | To elicit critically ill patients' experiences of nursing care in the adult ICU | Qualitative descriptive study Purposive sampling (n = 16 patients). |

Semi-structured interviews | Some patients had negative experiences regarding nursing care for the bad communication and for feeling that the presence of the nurses was scarce and they only saw them when they had to perform some procedure | SRQR Excellent |

| Kisvetrová et al,35 Czech Republic | To assess the practice of registered nurses (RNs) with respect to dying care and spiritual support interventions in ICUs | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study Convenience sampling (n = 277 ICU nurses) |

Questionnaire ad hoc | Activities focused on the spiritual needs of the patient like treating him with dignity and respect, biological dimension activities like “monitor pain” or “assist with basic care” were the most often provided activities in the care. Less frequently used activities were “communicate willingness to discuss death”, “offer culturally appropriate foods”, and “facilitate discussion of funeral arrangements” | STROBE 18/22 |

| Koukouli et al,24 Greece | To explore the experiences, needs and coping strategies of families of patients admitted to adult ICU of three hospitals in the island of Crete, Greece | Qualitative study Non-random purposeful sampling (n = 14 ICU patient's family members) |

Semi-structured, face to face interviews | The main coping mechanisms used were optimism, support from their family networks and spirituality. Spirituality as a means to deal with a difficult situation emerged as an original and significant finding in this particular cultural context underscoring the importance of recognizing, respecting and meeting families' spiritual needs | SRQR Excellent |

| Küçük et al,37 Turkey | To identify the effect of spiritual care given to mothers with infants in NICU on their levels of stress | Randomized controlled trial Random sample (n = 62 mothers, randomly divided into a spiritual care group (n = 30) and a control group (n = 32) |

The Mother–Baby Introductory Information Form and the Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PSS:NICU) | Following spiritual care, there was a significant difference between the PSS:NICU scores of the mothers, for the Infant's Appearance and Behaviours subscale, in favour of the spiritual care group (P < .05) The mothers stated that they cope their children's health problems acting on their spiritual feelings by fulfilling the practices of their religious beliefs like to pray or to read the Quran |

CONSORT 21/25 |

| Lundberg and Kerdonfag,50 Thailand | To explore how Thai nurses in ICU provided spiritual care to their patients | Qualitative study Purposive sampling (n = 30 ICU nurses). |

Semi-structured interview | The nurses stated that spiritual care involves communication with patients and patients' families, assessing the spiritual needs and showing respect and facilitating family participation in care. They assessed the quality of spiritual care in terms of understanding, compassion and empathy. All nurses expressed that they gave patients and relatives' mental support and comfort | SRQR Good |

| Moradnezhad et al,49 Iran | To evaluate the level of spiritual intelligence among nurses working at ICUs of hospitals affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 400 ICUs and CCUs nurses) |

King's Spiritual Intelligence Inventory |

About 51 ICU nurses enjoyed high spiritual intelligence (21%) and for 76.25% of nurses, spiritual intelligence was in moderate level. In addition, 2.75% had low levels of spiritual intelligence | STROBE 16/22 |

| Nascimento et al,32 Brazil | To describe the meaning of spirituality according to nurses who had worked in PICUs and how they provide spiritual care to children and their families | Qualitative study (n = 11 PICU nurses) |

Interviews | The meanings of S-R were described in different ways, but as interconnected concepts Nurses recognized that spiritual needs were less importance than physical treatments, and the spiritual care was indirectly provided through their families, respecting their beliefs and providing them the opportunity to express this in the PICU, such as allowing the presence of significant or religious objects that were close to the sick child. Nurses perceived that when they stimulate and respect the family's faith, positive thinking, and belief in God they were also reducing anxiety towards the child's illness |

SRQR Good |

| Ntantana et al,58 Greece | To assess the opinion of ICU personnel and the impact of their personality and religious beliefs on decisions to forego life-sustaining treatments | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 149 doctors and 320 nurses) | End-of-Life (EoL), Attitudes, Personality (EPQ) and SpREUK questionnaires | Personality and religious characteristics influence end-of-life issues. Working as a nurse and high religiosity were associated to the lack of foregoing life-sustaining treatments | STROBE 19/22 |

| Penha and Silva,45 Brazil | To identify the meaning of spirituality for the ICU nursing staff and to investigate how the professionals' spirituality values intervene in the care process | Qualitative study (n = 34 ICU nurses) | Semi-structured interviews | Spirituality was related to expression of religious life, and the idea of belief in a higher force or power. Religious values were manifested from a curative perspective, through divine intermediation of God in situations of human suffering. | SRQR Good |

| Pilger et al,44 Brazil | To understand the perception of nurses working in an adult ICU regarding S-R | Qualitative study (n = 9 ICU nurses) | Semi-structured interview | The assistance offered is guided by the influence of S-R beliefs of the professionals of the unit, and also by the appreciation of the S-R of patients Nurses considered the barriers to provide spiritual attention such as high workload, lack of nursing education or cultural differences and stated that the lack of encouragement from their superiors, the lack of periodic breaks and timely payments were the cause of their lack of motivation |

SRQR Good |

| Plakas et al,26 Greece | To explore the religious related experiences of relatives of ICU patients | Qualitative study (n = 19 interviews with 25 Greek-speaking adults visiting ICU patients) |

Interviews (“religiosity” was discussed in 15 out of the 19 interviews) | There was a positive interrelation between religion and coping. Participants' responses indicated that religiosity was a very important factor in dealing with their situation. According to Greek Orthodox tradition, and in other religions, asking God for help in difficult situations is a premise. Going to church or the monastery, praying or performing religious practices relieved negative emotions and gave them strength and hope by improving the religiosity of the participants and believing that this could positively affect their health outcomes |

SRQR Excellent |

| Riahi et al,8 Iran | To investigate the effect of spiritual intelligence training on the nurses' competence in spiritual care in the ICU | Quantitative study (semi-experimental study with two group pretest–post-test design) n = 82 ICU nurses, (40 in the experimental group and 42 in the control group) | Scale for Assessment of the Nurse's professional Competence in Spiritual Care (SANCSC) and the King's Spiritual Intelligence Inventory | After training spiritual intelligence, it increased significantly among nurses (P < .05). Despite lack of time, the lack of staff, cultural differences or the high workload perceived, nurses received approximately 80% of score of attitude toward spirituality and spiritual care score | CONSORT 19/25 |

| Sadeghi et al,25 Iran | To explore the spiritual needs of Iranian families at the end of their baby's life and through bereavement, from families' and professional health care providers' perspectives in the NICU | Qualitative study Purposive sampling (n = 24 participants: 14 parents and grandparents, 9 nurses and 1 doctor) |

25 semi-structured interviews (one mother was interviewed twice) | The most important identified spiritual needs were belief in a supernatural power or belief in God. They want to be healed and revived by God. In the participants' view, the need for hope, the need for peace, and the need for understanding and empathy were very important spiritual needs in neonatal end of life and bereavement. The health care professionals considered communication with families and listening to them with empathy as a spiritual need | SRQR Excellent |

| Schleder et al,12 Brazil | To assess spiritual/religious coping of relatives of patients hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit of two hospitals | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study. Non-probability sampling and convenience (n = 45 ICU patient's family members) |

Spiritual/Religious Coping Scale (SRCOPE scale) | Family members use more positive SCR strategies than negative ones while their loved one is hospitalized in the ICU, believing that spirituality/religion has helped in managing to cope with stress The dimensions that showed higher values were “Positive position towards God”, “Distancing through God, religion and/or spirituality” and “Transformation of oneself and/or one's life” |

STROBE 16/22 |

| Sierra and Montalvo,56 Colombia | To determine the degree of spiritual wellness of nurses serving in ICU in Cartagena (Colombia) | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study Randomized sample (n = 101 ICU nurses) |

Reed's Spiritual Perspective Scale | The majority of nurses (98%) had a high spiritual wellness and considered spiritual beliefs as a very important part of their lives (69.3%), used to feel close to God or a superior (60.4%), and performed practices like prayers (69.3%) or meditation (57.4%) | STROBE 14/22 |

| Sonemanghkara et al,41 USA | To explore the lived experience and interactions of patients' families, nurses, and chaplains when patients or family request pastoral care interventions in an ICU setting | Qualitative study n = 18 (6 patient's family member, 6 nurses and 6 chaplains) |

Interviews | The general care provided by nursing staff and chaplain services was seen as positive by the families. Among nurses, 83% reported that when discussing death with a family member, they also inquired about initiation of chaplaincy services | SRQR Excellent |

| Taheri-Kharameh,57 Iran | To determine attitude of intensive care nurses towards spirituality and spiritual care and its relationship with mental health | Quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study (n = 55 ICU nurses of educational hospitals) | SSCRS and General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) | Nurses' attitudes to spirituality and spiritual care were in a moderate range (55.95 points), and a significant correlation with age (r = 0.491, P = .006) and work experience (r = 0.496, P = .004). Positive and significant correlation between attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care and mental health in intensive care nurses were also reported (r = 0.348, P = .02) | STROBE 17/22 |

| Turan and Karamanoğlu,51 Turkey | To determine ICU nurse's perception and practice status of spiritual care, and it was determined that the perception status of nurses regarding spiritual care is better than their practice status | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study (n = 135 ICU nurses) | The Spiritual Care Perceptions and Practices Scale |

The status of nurses' actual practice of spiritual care was found to be considerably lower than their perception status and that the nurses that have higher perception of spiritual care also have higher scores in the practice of spiritual care. Most of the nurses failed to register data concerning the spiritual care of a patient might be because of the heavy work schedule or they are understaffed or that they lack relevant knowledge | STROBE 18/22 |

| Willemse et al.,47 Netherlands | To map the role of spiritual care as part of daily ICU care in adult ICUs from the perspective of intensivists, ICU nurses, and spiritual caregivers | Quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study n = 487 participants (99 intensivists, 290 ICU nurses and 98 spiritual caregivers) |

Questionnaires ad hoc | More than 70% of the sample indicates that providing SC improves the quality of care in patients and their families and quality of life and their satisfaction. Most of respondents (66%) indicated that they had enough time to provide spiritual care but mentioned barriers such as too much homework, patient complexity, and too few spiritual caregivers | STROBE 17/22 |

Seventy-five percent of the included papers were published between 2015 and 2019 and 10 articles (25%) were published in the period between 2010 and 2014. Fifteen articles (37.5%) were from Asia, followed by eight studies (20%) from Europe, seven studies (17.5%) from North America, six studies (15%) from South America, three studies (7.5%) from Africa and only one study (2.5%) from Oceania. In relation to the sample, 32 studies were carried out with adults (80%), while eight articles included relatives of paediatric or neonatal patients.

Among 3401 health care providers included in the quantitative studies, 86.6% (n = 2945) were nurses. After the assessment using the Equator guidelines (STROBE guideline for observational studies and CONSORT guideline for parallel group randomized trials) all papers included in this review were considered of high or medium quality of reporting, scoring from 14 to 20 out of 22 in the STROBE and 21 out of 25 in the CONSORT.

Seventeen qualitative studies included health care professionals as participants, and most of them included only nurses (76.47%). Twelve qualitative studies included family members and patients, both exclusively (66.7%) and being together with health care providers (33.3%).

After the assessment using the SRQR standards for qualitative studies, no article was rejected, because they fulfilled most of the items. However, the most frequently detected deficiencies were related to the description of the interview scripts and the characteristics of the researchers.

Our analysis of findings from the papers resulted in the creation of seven themes: S-R importance and the use of coping in critical care patients and families; Spiritual needs of patients and families; Health care professionals' awareness to spiritual needs; Ways to address spiritual care in the ICU; Definition of S-R by health care professionals; barriers of addressing patients' and families' spiritual needs; and Influence of S-R on health care professionals' competencies and families' decisions. In this section, we opted to not separate the results between adult and paediatric critical care studies, because the results of these studies shared similarities. However, possible different views/experiences/practices have been considered as a point to be discussed.

4.2 S-R importance and the use of coping in critical care patients and families

In the included studies, ICU patients (both adults and children) and their relatives used religiosity and spirituality as strategies to cope with adverse situations and critical conditions.12, 24 For instance, in Iran, Sadeghi et al25 showed that a high degree of faith and trust in God, and the acceptance of the catastrophe as a Divine test, facilitated adaptation to the children's death. Although most families were using S-R as a hope for healing, mothers believed that they would meet their children in another world and the pain they were suffering would gain eternal rewards to them. In the same line, Schleder et al12 found that 42.2% of the members of Brazilian families believed that S-R could help in the stress they were experiencing and Plakas et al,26 who carried out a study in Greece, showed that relatives who believe that God determines everything, felt more emotional comfort and less grief for the death of their loved ones.

The use of religiosity and spirituality as coping strategies has an influence on family outcomes as well. Brelsford et al27 found that religious coping strategies were related to proper family functioning in the United States, while negative coping, such as feeling of being abandoned or punished by God, was associated with lower levels of family cohesion.

4.3 Spiritual needs of patients and families

Most patients want nurses to understand and respect their values and beliefs, guaranteeing the coverage of their cultural, S-R needs.25, 28, 29

In countries with higher religious commitment, such as Muslim countries, patients' needs include religious practices and traditions such as attending temples, praying in churches and monasteries. Plakas et al26 report findings from a non-Muslim country suggesting that reciting the Qur'an and the Shahadatain, appealing to imams,26 or even donating on behalf of their relative in the hope that this donation will facilitate admittance to heaven or the healing of the disease.25, 30 Other needs of patients and their families were to have a place in the ICU where patients can be closer to their relatives, as well as the presence of a pastor to pray for critically ill patients. However, the participants stated that they did not get this spiritual support.31

In the case of paediatric critical care, the dignity of the baby was one of the most important spiritual needs of the Iranian families studied by Sadeghi et al.25 They revealed that most mothers expressed their desire to communicate with other mothers who had lost their children, because they wanted to feel that they were not alone and they shared similar experiences. In another study, paediatric critical care nurses from Brazil found that promoting faith and belief in God was a potential intervention they could use to address parents' spiritual needs, positively influencing child's well-being as well.32

4.4 Health care professionals' awareness to spiritual needs

Despite the importance placed by patients and family members on spiritual needs, studies have shown that health care professionals and nurses still pay little attention to these aspects of critical care. Despite the different cultural contexts, Alimohammadi et al33 and Choi et al34 found that religious and spiritual needs in the ICU had lower priority as compared with acute medical needs. Kisorio & Langley29 also reported that some South African nurses were concentrating only on the technological aspects of care, resulting in patients feeling neglected and dehumanized. Although Kisvetrová et al35 showed that ICU nurses in Czech Republic “respect the need for privacy” and “support the family's efforts to remain at the bedside,” spiritual support interventions were not offered commonly or routinely.

4.5 Ways to address spiritual care in the ICU

The results showed that spiritual care in the ICU is mostly offered during visits by family members and/or religious leaders. However, some initiatives include the direct or indirect participation of nurses and other health care professionals.

As an example, ICU nurses provided Muslim parents privacy to spend more time with their children and pray, offering them an audio recording of the Quran, and accepted practices such as the use of Zamzam water (i.e. Holy water recovered from the well of Zamzam in Mecca), Muslim rituals of body orientation towards Mecca after the baby dies and the use of cevşen-muska (a small amulet with small prayers from the Quran) on the incubator.36, 37 In another study, families were concerned to minimize touching the body of the dead Muslim as much as possible by the health care providers if they are not of the same sex of the patient.38

In the non-Muslim context,39 nurses acknowledged that parents needed time to spend with critically ill baby and to be able to hope for a Divine intervention.

Despite the focus of most of the papers on nursing care, some studies carried out in western countries also highlight that spiritual care should be provided by all members of the health care team, in addition to chaplains40, 41 and other hospitals' spiritual care services.42

4.6 Definition of spirituality/religiosity by health care professionals

Our analysis showed that participants in the studies included in the review appeared to have difficulty in differentiating between religiosity and spirituality. On the one hand, most nurses in a study in Palestine defined the terms spirituality and spiritual care within the context of religion43 and in Turkey and Brazil, nurses provided spiritual care to their patients and relatives based on their religious beliefs.3, 44 On the contrary, another study,45 reported that Brazilian nurses had four different meanings for the spiritual dimension (i.e. faith and religious belief, belief in a higher force/power, spiritual well-being and attribute of the spirit).

4.7 Barriers of addressing patients' and families' spiritual needs

ICU nurses believe S-R may have a positive influence on patients' health, providing peace, comfort, faith and hope.46 In the study carried out by Willemse et al47 in Netherlands, more than 80% of ICU professionals (critical care physicians, nurses and spiritual caregivers) considered that the cultural background of patients and their S-R beliefs were very important in the way they face the illness.

Iranian studies also revealed that most of the nurses believed that the need for spiritual care is the missing part of patient care,33 and families need to have their religious and spiritual beliefs respected.48, 49

Although nurses commonly recognized spirituality as an important component of holistic care in critical situations,50 addressing S-R needs of the patients was considered a difficult task32 and many nurses felt they were not prepared to provide appropriate spiritual care.42, 51, 52

In the study of Willemse et al,47 more than 70% of nurses highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and, although 66% of them felt qualified to provide spiritual care, more than 74% of intensive care physicians and nurses believed this approach was time-consuming8, 47 and, for this reason, resorted to spiritual care provided by caregivers or chaplains. The provision of S-R care by ICU health care professionals is not only influenced by knowledge and attitudes, but also by other factors such as age,53 burnout levels, clinical experience,54 job stress,55 work overload, low level of personnel,51 cultural differences and the lack of incentives from their managers (i.e. the lack of periodic breaks and timely payments).44

4.8 Influence of S-R on health care professionals' competencies and families' decisions

In this review, some studies have investigated the concept of spiritual intelligence. Spiritual intelligence includes the development of a positive evaluation and implementation of spiritual care, human values, awareness, attitudes and self-recognition.14, 53, 56, 57 It also includes characteristics such as faith, humility, the ability to control one's feelings, ethics, forgiveness, appreciation and love. This allows the use of spirituality to solve problems and achieve goals, with inner and outer calmness under any circumstances.8 Higher levels of spiritual intelligence are associated with spiritual care competence of health care professionals as shown in our findings.

Two studies have also assessed the influence of S-R on health care professionals' and families' decisions. Ntantana et al58 showed that both the religiosity of nurses and certain personality traits have an influence on decision-making regarding the withdrawal of life support measures. Likewise, approximately 77% of critical care relatives considered S-R very important for surrogate decision makers, because S-R helps them to provide a substituted judgment on behalf of their loved one.59

5 DISCUSSION

The analysis of the findings from the included studies show that patients and their families use spiritual/religious coping strategies to alleviate stressful situations in the ICU and that respecting patients' spiritual beliefs is an essential component of critical care. Although nurses consider spiritual care to be very important, they do not feel prepared to address it and lack of time is identified as a barrier.

Spiritual/religious coping strategies can be positive (i.e. “Positive position towards God,” “Transformation of oneself”) and negative (i.e. Distancing through God,” and “Negative position towards God”).12 They could result in different outcomes, related to a decrease of the period of hospitalization and the severity of the situation,60 which impact the health of the critically ill patient. Therefore, because this component has an important influence on critical care, nurses should be aware of it and trained to handle such issues in practice.

S-R are associated with positive physical and psychological outcomes among myocardial infarction patients,61 cancer patients and those receiving palliative care. In these groups, spiritual support has been associated with improvement in quality of life and well-being.62 Other studies have shown that facilitating religious practices allows negative emotions such as anticipatory grief, uncertainty, agony, fear and anxiety to be turned into positive emotions.26 These strategies can be used even in patients receiving mechanical ventilation where image-guided spiritual care was a useful tool for reducing anxiety and stress during the ICU stay and the post-admission period.63

Although religious leaders participate in a large number of activities related to supporting religious and spiritual needs and providing support for family and improve the decision-making process and family satisfaction with ICU care,64 most of this assistance only comes when the patient is in end-of-life care.65 Nurses should be able to identify if patients and their relatives wish to involve religious leaders or chaplains.

In our findings, nurses considered that addressing S-R issues is important48 and they value the positive effects on patients and their families.57 However, several reasons are pointed as barriers that prevent nurses to address S-R. The most common barrier is that nurses think their training has not prepared them adequately to address ICU patients' and their families' S-R.42 Although the lack of training is evident, nurses recognize that spiritual intelligence is valuable and there is willingness to continue their education on spiritual issues.66 Therefore, providing more training to increase the knowledge and skills of health care professionals while providing spiritual care is pivotal in critical care environments. Even when there are important language barriers, nurses were able to facilitate Muslim religious practices respecting for diversity, acknowledging differences according to nationality, using professional translators and understanding Muslims' views of death.36

This review has found that there are cultural differences between countries and health care professionals. It is important to highlight that secular societies (such as some countries in Europe) tend to be more restrictive on addressing S-R in clinical practice. On the other hand, Asiatic cultures tend to be more open to the incorporation of spirituality in clinical practice, because some of their therapies are intrinsically connected to a “High Power.” Likewise, Muslim countries tend to be more religious and, for this reason, more open to the incorporation of specific religious practices as evidenced in our results and by other authors.4-6 These findings reveal that different countries have different ways to address S-R in critical care and these peculiarities should be considered by health care professionals. The accepted spiritual/religious practices for some cultures may be totally unaccepted in other cultures and critical care professionals should recognize these differences. As shown in a previous systematic review, a wide degree of heterogeneity is observed within religions in palliative care practices such as advanced directives, euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, physical requirements (artificial nutrition, hydration, and pain management) and autopsy practices.67

Recent studies showed a positive correlation between the competence of spiritual care with the spiritual well-being of nurses and their attitude towards spirituality.68 Wu et al66 also revealed that positive spiritual climate supports transformational leadership as means to reduce nursing burnout. In addition, previous studies have showed that the attitude of spiritual care was rooted in faith and spiritual beliefs69 according to which nurses considered spiritual care as a professional responsibility that must be treated with the same level of attention as physical needs.70 All this evidence could help in the development of training and in the improvement of spiritual care in critical patients.

6 LIMITATIONS

The present review has some limitations that should be acknowledged. It is possible that our search strategy has not included all possible keywords and, as a result, failed to retrieve and include some important articles. The inclusion and exclusion criteria could be not exhaustive or fully comprehensive. On the one hand, future studies on this topic should indicate specific characteristics of S-R care to identify those articles that meet these criteria. However, this could be complicated because of the lack of consensus on the definition of concepts such as S-R. On the other hand, the date limits used in this study have excluded older studies. Although this is a limitation, we decided to include the most up-to-date evidence in this review, since guidelines, clinical practices and evidence change in a rapid pace. Most studies included in this review were from Asian countries, which are usually more open to spiritual needs as compared with some secular societies. This could have influenced our findings. Finally, as previously mentioned, although we recognize that paediatric and adult critical care are different in some aspects, they carry important similarities and, for this reason, we decided to include all studies with critically ill patients in the review, broadening its scope and adding to the literature. Future studies should deepen the knowledge on how spiritual care is addressed by nurses worldwide, the differences in cultural backgrounds and the mechanism by which S-R issues may influence the physical and mental health of critical patients and their families.

7 IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATION FOR PRACTICE

This review indicated spiritual needs are commonly expressed during life-threatening situations, such as those experienced in ICUs, life-threatening conditions and health care professionals should be aware of them. Because our results highlight that most nurses are open to this subject and would like to be trained to handle these situations, ICU managers are commended to organize training for ICU health care professionals in order to provide a more holistic care.

8 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this review has demonstrated that spirituality is an important issue for critical care patients, family members and health care professionals. Critical care professionals should be aware about the needs of their patients and should be trained to handle S-R in clinical practice.

8.1 Impacts

8.2 Ethics practices

During this review, ethical practices were applied. The authors have aimed for transparency, accuracy and the avoidance of plagiarism. The review followed a structured guideline provided by Whittemore et al.19

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Study conception and design: Bárbara Badanta, Rocío de Diego-Cordero. Data collection: Bárbara Badanta, Estefanía Rivilla-García. Data analysis and interpretation: Bárbara Badanta, Estefanía Rivilla-García, Rocío de Diego-Cordero. Drafting of the article: Bárbara Badanta, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Rocío de Diego-Cordero. Critical revision of the article: Bárbara Badanta, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Rocío de Diego-Cordero.