Molecular Identification and Antifungal Susceptibility of Fusarium spp. Clinical Isolates

Carla M. Román-Montes and Fernanda González-Lara have contributed equally to this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

Accurate identification of Fusarium species requires molecular identification. Treating fusariosis is challenging due to widespread antifungal resistance, high rates of treatment failure, and insufficient information relating antifungal susceptibility to the clinical outcome. Despite recent outbreaks in Mexico, there is limited information on epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility testing (AST).

Objectives

We aimed to analyse the distribution of Fusarium species from a referral centre in Mexico with DNA sequencing and to describe AST to the clinical outcome.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on clinical isolates of Fusarium. They were identified by translation elongation factor-1α gene amplification and sequencing. AST was performed to determine minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs).

Results

A total of 35 Fusarium isolates from 26 patients were included. The most common was Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC) in 51.5%, of which Fusarium petroliphilum and Fusarium oxysporum species complex were the most frequent with 37% and 20%, respectively. AST did not show MICs above the epidemiological cut-off value. Fusariosis was diagnosed in 19 patients, mostly with hematologic neoplasm; the overall mortality rate was 32%.

Conclusions

Fusarium petroliphilum from the FSSC was found most frequently. Elevated mortality and MICs for all tested antifungals were found, with higher MIC50 among F. solani SC than F. oxysporum SC or F. fujikuroi SC.

1 Introduction

Fusarium species are ubiquitous fungi that are widely distributed in the environment, soil, and organic substrates, including hospital water distribution systems and seawater. They are important plant pathogens causing agricultural losses. In humans, most cases include superficial infections, such as keratitis or onychomycosis; locally invasive or disseminated infections may occur in immunocompromised individuals [1]. Although the incidence of fusariosis may be variable, it may be increasing among patients with acute leukaemia and stem cell transplant with prolonged neutropenia. Most cohorts are from Brazil or France, but the number of case reports has increased steadily increased worldwide, even in solid organ transplants [2-7].

More than 300 phylogenetically different species of the genus Fusarium grouped in more than 20 species complexes (SCs) have been described. There is geographic variation in species distribution, but Fusarium solani SC (FSSC), Fusarium oxysporum SC (FOSC), and Fusarium fujikuroi SC (FFSC) are the most prevalent. Historically, microscopic observation of typical spindle- or canoe-shaped multicellular macroconidia allowed for the identification of Fusarium. Although morphological identification of key features may allow genus recognition, it requires expert training and the use of standardised culture media. DNA amplification and sequencing has led to a better understanding of the epidemiology and species distribution using β-tubulin gene and partial regions of EF1α that have more discriminatory power for Fusarium [8-10]. Accurate species identification by molecular methods may be available only in reference laboratories [11, 12].

A significant number of Fusarium strains exhibit high minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) toward most antifungals. Epidemiological cut-off values (ECVs) for itraconazole (ITR), posaconazole (POS), voriconazole (VOR), and amphotericin B (AMB) in FOSC, FSSC, and F. verticillioides, have been established [13]. Insufficient data on less frequent species and scarce information describing the correlation between the MICs and the clinical outcome are recognised [14-17].

Our aim was to analyse the distribution of Fusarium species from a referral centre in Mexico using DNA sequencing and to describe AST in relation to the clinical outcome.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Strains

Fusarium isolates collected from 2014 to 2021 were extracted from storage at −80°C in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. Our centre is a referral hospital for adult patients with haematological and solid cancer, organ transplant, autoimmune and chronic diseases. Isolates were subcultured in Sabouraud agar and incubated at 30°C until sporulation. SC and species identification were achieved through amplification and sequencing of the translation elongation factor-1α gene (EF1α).

2.2 Fungal DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing Analysis

A Sabouraud broth subculture was kept rotating at room temperature (15°C–25°C) for 48–72 h. After centrifuging, the fungal mass was transferred to sterile tubes and washed with sterile water. Fungal wall rupture was performed using microbeads and a Precellys Evolution Homogeniser (Berlin Instruments, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France). E.Z.N.A. Fungal DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) was used for DNA extraction.

The primers used were EF-1 5′-ATGGGTAAGGARGACAAGAC-3′ and EF-2 5′-GGARGTACCAGTSATCATG-3′ as recommended by the MM18-A (CLSI April 2008). The final mix comprised 25 μL, containing 1X buffer, 1 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs (Roche Diagnostics, Germany), 0.5 pmol of each primer, 1U Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher, Scientific Baltics UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania), and 100 ng DNA. The cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 35 cycles at 95°C for 45 s, 50°C for 45 s, 72°C for 60 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were analysed using agarose gel electrophoresis. Products of 700 bp were purified with PCR QIAquick spin (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands).

Sanger sequencing was performed using the automated sequencer 3500 (Applied Biosystems Hitachi, San Francisco, USA). The reaction was carried out in a final volume of 10 μL, using 1 μL of the primer, 3 μL of BigDye terminator (Applied Biosystems), and 100 ng of DNA. The sequences were aligned using ClustalW, analysed, edited, and compared with those found in the base of GenBank and Fusarium MLST database (https://fusarium.mycobank.org/). Subsequently, to obtain the definitive identification, the sequences were used for phylogenetic tree construction as the best evolutive model and a maximum likelihood (ML) analysis with MEGAX with a non-parametric bootstrap using 1000 replicates.

2.3 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

Broth microdilution testing was performed for ITR, VOR, POS, and AMB from Sigma Aldrich, within the range of 0.03–16 μg/mL, following CLSI guidelines (M38 3rd Edition). Spores were collected in a 2 mL solution from a Sabouraud agar culture, kept at 30°C. After allowing the heavy particles to settle for 5 min, the suspension was transferred to a sterile tube and the adjusted to a spectrophotometer reading of 0.15–0.17 at A530. A 1:50 dilution was prepared, and 100 μL of this dilution was inoculated into the microdilution plates. The plates were then incubated at 35°C for 46–50 h. The MIC was determined as the point where visual growth was completely inhibited. It was interpreted based on the established ECVs by Espinel-Ingroff et al., which are described in Table 1. Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC MYA3626, Candida parapsilosis ATCC 20219, and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 were quality control strains. Sterility and growth control were used [13].

| Species or species complex | Antifungal | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Fusarium solani species complex |

ITR VOR POS AMB |

32 32 32 8 |

| Fusarium oxysporum species complex |

ITR VOR POS AMB |

32 16 8 8 |

| Fusarium verticillioides |

ITR VOR POS AMB |

ND 4 2 4 |

- Note: Table extracted from A. Espinel-Ingroff et al. Reference number 13.

- Abbreviations: AMB, amphotericin B; ITR, Itraconazole; ND, no data; POS, posaconazole; VOR, voriconazole.

For isavuconazole (ISA) susceptibility, we performed an E-test using Liofilchem Diagnostic, with a concentration range of 0.002–32 μg/mL. After being incubated on Sabouraud agar at 30°C, the spores were collected in a 2 mL saline solution. After allowing heavy particles to settle for 5 min, the suspension was transferred to a sterile tube and then adjusted to a spectrophotometer reading of 0.15–0.17 at A530. Inoculation was done using RPMI plate media. The strip was applied following the manufacturer's instructions. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 35°C, and the MIC was determined at 80% inhibition as indicated by the manufacturer.

2.4 Clinical Data

Clinical data were obtained from clinical records. Demographic and clinical variables were recorded for analysis. We used the EORTC/MSG criteria to determine probable or proven fusariosis. When these criteria were not met, isolates were considered as colonisation [18].

2.5 Ethics

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán INF-3691-21-22-1.

3 Results

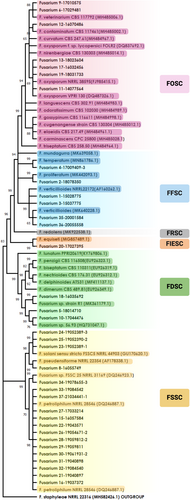

A total of 35 Fusarium spp. isolates were collected from 26 patients. The most frequent isolates were FSSC in 51.5% (18/35), followed by FOSC in 20% (7/35) and FFSC in 17% (6/35), Fusarium dimerum SC (FDSC) in 8.5% (3/35) and 3% (1/35) of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti SC (FIESC).

Table 2 describes the species level identification within the SCs. Of the FSSC species, the most common was Fusarium petroliphilum in 72%. Three isolates of FDSC could not be identified at the species level, they had a match < 90% with FDSC by Fusarium MLST database, while in GenBank two isolates matched (100% and 99.8%) with Fusarium sp. No. 56.93 (GenBank HQ731047). These isolates grouped perfectly with the sequence of Fusarium sp. No. 56.93 when this sequence was included in the phylogenetic tree. The remaining isolate had low percentage matches with Fusarium sp. strain R1 (GenBank MK361179) in 98.1%, Fusarium sp. strain 56.93 in 94.9% and Fusarium dimerum strain FRC E-325 (GenBank JN235513.1) in 90.6%. The sequences of our three isolates are in GenBank (MW086554, MW086555 and MW086556).

| Fusarium species complex | N = 35 (%) | Identification at species level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC) | 18 (51.5) |

Fusarium petroliphilum Fusarium solani sensu stricto FSSC5 Fusarium pseudensiforme Fusarium sp. FSSC25 |

13/18 (72) 3/18 (16) 1/18 (6) 1/18 (6) |

| Fusarium oxysporum species complex (FOSC) | 7 (20) |

Fusarium oxysporum SC Fusarium veterinarium Fusarium contaminatum |

4/7 (57) 2/7 (28.5) 1/7 (14.5) |

| Fusarium fujikuroi species complex (FFSC) | 6 (17) |

Fusarium verticillioides Fusarium proliferatum Fusarium temperatum |

4/6 (67) 1/6 (16.5) 1/6 (16.5) |

| Fusarium dimerum species complex (FDSC) | 3 (8.5) |

Fusarium sp. 56.93a Fusarium, probable new species (1) |

2/3 (67) 1/3 (33) |

| Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC) | 1 (3) | Fusarium equiseti (1) | 1/1 (100) |

- Abbreviation: ND, no data.

- a Fusarium species without name, founded in BLAST as 56.93.

Regarding seven FOSC isolates, two were identified as F. veterinarium and one as F. contaminatum, the remaining four, were not identified to the species level and remained as FOSC since they were grouped with two sequences described as F. oxysporum; however, they are not described sensu stricto.

Figure 1 is an ML phylogenetic tree describing species distribution within five different complexes using the EF1α gene.

3.1 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

The MICs distribution is shown in Tables 3 and 4. All had ITR MICs ≥ 16. The azoles had reduced activity among FSSC, with an MIC50 for VOR and POS > 16 and > 32 for ISA, while the MIC50 for AMB was 4. None of the FSSC had MIC < 2 for AMB and 2/18 (11%) isolates had an MIC of 2 for AMB. Despite elevated MICs, no FSSC were above the ECV for azoles or AMB.

| Species complex (n) | Antifungal | MIC rang μg/mLe | MIC 50/90 | Number of isolates by MIC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | ≥ 16 | ||||

| F. solani (18) | ITR | ≥ 16 | > 16/> 16 | 18 | ||||||||

| VOR | 4 to ≥ 16 | > 16/> 16 | 1 | 4 | 13 | |||||||

| POS | ≥ 16 | > 16/> 16 | 18 | |||||||||

| AMB | 2–4 | 2 | 15 | 1 | ||||||||

| F. oxysporum (7) | ITR | ≥ 16 | > 16/> 16 | 7 | ||||||||

| VOR | 2 to ≥ 16 | 4/> 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| POS | 0.5 to ≥ 16 | 4/> 16 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| AMB | 2–8 | 4/8 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| F. fujikuroi (6) | ITR | ≥ 16 | > 16/> 16 | 6 | ||||||||

| VOR | 1 to ≥ 16 | 2/> 16 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||||||

| POS | 0.5 to ≥ 16 | 1/> 16 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| AMB | 1–4 | 2/4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| F. dimerum (3)a | ITR | ≥ 16 | Nd | 2b | ||||||||

| VOR | 2–8 | Nd | 1 | 1b | ||||||||

| POS | ≥ 16 | Nd | 2b | |||||||||

| AMB | 1–4 | Nd | 1b | |||||||||

- Abbreviations: AMB, amphotericin B; ISA, isavuconazole; ITR, itraconazole; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; Nd, no data; POS, posaconazole; VOR, voriconazole.

- a One isolate of F. dimerum SC without susceptibility test.

- b Correspond with new Fusarium species.

| Species complex (n) | Antifungal | MIC range μg/mL | MIC 50/90 | Number of isolates by MIC | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.5 | 0.75 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 4.5 | 6 | 12 | 24 | ≥ 32 | ||||

| F. solani (18) | ISA | ≥ 32 | ≥ 32/≥ 32 | 9 | |||||||||

| F. oxysporum (7) | ISA | 0.75 to ≥ 32 | 4/32 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| F. fujikuroi (6) | ISA | 0.47 to ≥ 32 | 1.5 to ≥ 32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| F. dimerum (3)a | ISA | ≥ 32 | Nd | 2 | |||||||||

- Abbreviation: ISA, isavuconazole.

- a One isolate of F. dimerum SC without susceptibility test.

Among FOSC, the MIC50 for VOR, POS, ISA and AMB was 4, two isolates (28.5%) had MICs above the ECV for POS and one (14%) for VOR. Similar to FSSC isolates, none of the FOSC had MIC < 2 for AMB and three isolates had MIC 2 for AMB. FFSC showed the lowest MIC50: 2 for VOR and AMB, 1 for POS and 1.5 for ISA. Then, 75% (3/4) of F. verticillioides showed MIC of 4 μg/mL for AMB equal to ECV, unlike what has been observed for the F. temperatum and F. proliferatum isolates which showed MICs 1–2 μg/mL for VOR, POS, and AMB.

3.2 Clinical Data

Only 21 patients had clinical data. Two were considered colonisation. Then, 19 patients had fusariosis, 58% (11/19) probable, and 42% (8/19) proven fusariosis. Among patients with fusariosis, 58% (11/19) were male with mean age of 51.5 (SD 17.9), 47% (9/19) were originally from Mexico City.

One patient with fusariosis had two FSSC isolates (F. pseudensiforme and F. petroliphilum) in the same clinical sample. The etiological agents were FSSC in 31.5% (6/19) of which three F. solani sensu stricto and only two F. petroliphilum and one F. pseudensiforme; FOSC in 31.5% (6/19) of which all were FOSC, FFSC in 16% (3/19) of which two were F. verticillioides and one F. proliferatum, FDSC in 16% (3/19) of which two were grouped with the Fusarium sp. 53.96 and one probable new species, and 5% (1/19) FIESC that was a Fusarium equiseti.

Hematologic neoplasm was the most frequent comorbidity in 32% (6/19) followed by pharmacologic immunosuppression in 21% (4/19) (rheumatic diseases or transplant). Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was present in 16% (3/19), lymphopenia in 68% (13/19) and severe neutropenia in 37% (7/19). Three patients had primary fusarium osteomyelitis, and a single case had fungemia.

Six-week mortality in all fusariosis patients was 32% (6/19). Antifungal treatment was indicated in 68% (13/19), of which 38% (5/13) were dead at 6 weeks. Of the six patients who did not receive antifungal treatment, one received palliative care, and five were considered colonised by physicians. Table 5 describes general characteristics of patients who received antifungal treatment. The 61.5% (8/13) patients who received antifungal treatment and were alive at 6 weeks had a median of 8 μg/mL VOR and AMB 4 μg/mL MIC, and 38.5% (5/13) who died had a median of 4 μg/mL VOR and 4 μg/mL AMB MIC.

| Sex/Age | Comorbidity | Corticosteroids | Site of infection | Antifungal treatment | Fusarium species | MIC ITZ | MIC VRZ | MIC PSZ | MIC AMB | MIC ISA | Six-week outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/67y | Chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes | Yes | Sinusitis | Voriconazole then Fluconazole (physicians consider colonisation) | F. solani sensu stricto | > 16 | 16 | > 16 | 4 | ≥ 32 | Dead |

| F/35y |

Acute leukaemia Severe neutropenia |

Yes | Sinusitis | Voriconazole and Amphotericin B |

F. pseudensiforme F. petroliphilum |

> 16 > 16 |

> 16 16 |

> 16 > 16 |

4 ≥ 32 |

≥ 32 ≥ 32 |

Alive |

| M/68y |

Chronic liver disease Severe neutropenia |

No | Lung disease | Voriconazole and Amphotericin B | F. petroliphilum | > 16 | 8 |

> 16 |

4 | ≥ 32 | Dead |

| M/45y | HIV/AIDS | No | Lung disease | Itraconazole and Voriconazole | F. solani sensu stricto | > 16 | 8 | > 16 | 2 | ≥ 32 | Alive |

| F/70y |

Acute leukaemia Severe neutropenia |

Yes | Sinusitis | Voriconazole, Amphotericin B, Caspofungina | F. oxysporum SC | > 16 | 8 | > 16 | 4 | ≥ 32 | Dead |

| F/56y | Solid cancer | No | Fungemia | Anidulafungin, Amphotericin B | F. veterinarium | > 16 | 8 | > 16 | 4 | ≥ 32 | Alive |

| F/36y | Liver transplant | Yes | Esophagic | Fluconazole then Anidulafungin | F. oxysporum SC | > 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | ≥ 32 | Alive |

| F/27y |

HSCT Severe neutropenia |

Yes | Lung disease | Voriconazole, Amphotericin B, Anidulafungin | F. oxysporum SC | > 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 1.5 | Dead |

| M/23y |

Acute leukaemia Severe neutropenia |

Yes | Sinusitis | Amphotericin B, Voriconazole then Itraconazole | F. verticillioides | > 16 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | Alive |

| F/35y | Rheumatic disease | Yes | Sinusitis | Fluconazole then voriconazole | F. temperatum | > 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.47 | Alive |

| F/44y | Acute leukaemia | No | Sinusitis | Voriconazole, anidulafungin, Amphotericin B | F. equiseti | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Alive |

| F/78y | Solid cancer | No | Lung disease | Anidulafungin then fluconazole | Fusarium new species | > 16 | 2 | > 16 | 1 | ≥ 32 | Dead |

| M/26 | Acute leukaemia | NO | Sinusitis | Amphotericin B then Isavuconazole | F. solani sensu stricto | > 16 | > 16 | > 16 | 4 | Nd | Alive |

- Abbreviations: AMB, amphotericin B; HSCT, Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ISA, isavuconazole; ITR, itraconazole; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; Nd, no data; POS, posaconazole; VOR, voriconazole.

4 Discussion

We described molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profile of 35 Fusarium clinical isolates collected from 2014 to 2021, including 19 from patients with invasive infection. Among the more than 300 different species of Fusarium grouped into over 20 complexes, most medically important belong to seven SCs: FSSC, FOSC, FFSC, FIESC, Fusarium chlamydosporum SC, FDSC, and FSSC [19]. In this study, the most frequent was FSSC, which is globally the most frequent SC, followed by FOSC and FFSC [19, 20]. These results are similar to those from Brazil, Spain, France, and Qatar, and consistent with previous reports [5, 21-25]. A recent report from Mexico including 166 strains revealed a majority of FSSC followed by FFSC and FOSC, an increase in F. falciforme may be due to environmental samples from rural areas [26]. In contrast, a multinational study by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology found that FFSC was the most frequent cause of invasive infection, followed by FSSC [27]. One study reidentified 127 previously collected strains by sequencing of EF1α and rpb2 showed that the three most common species presented were F. falciforme, F. keratoplasticum (from the FSSC) followed by FOSC [28]. Geographic distribution, the inclusion of environmental versus clinical strains and the predominant type of patients included (nail and skin infections vs. disseminated) may influence SC distribution. Molecular identification has allowed a more precise delineation of species distribution within the complexes. In the past, most were referred to as a single species, and many remained identified at the genus level due to limited expert training and use of traditional mycologic identification.

Among FSSC individual species, F. petroliphilum was the most common in this study, which contrasts with other series where F. keratoplasticum is the dominant. This may be due to the association of F. keratoplasticum with keratitis or skin and nail infections, which none of our patients had [4, 21, 26, 29]. Also, although F. petroliphilum is not a new species, its status as a separate species within the FSSC is recent. A role of in invasive disease and keratitis has been described [30].

The species within FOSC have not been thoroughly elucidated. At least 26 sequence types have been described among several cryptic species, and although FOSC mostly causes devastating damage to crops, they have also been involved with human infections such as endophthalmitis outbreaks [31], disseminated disease, and onychomycosis [32]. In this study F. veterinarium, F. contaminatum, and FOSC were involved in superficial, pulmonary, and blood infections. Those species had not been individually linked to infections, since most studies report F. oxysporum as an SC, reinforcing the importance of molecular identification to further delineate their clinical impact [33]. EF1α gene region provided the best resolution to discriminate the novel species of FOSC [4, 26].

Fusarium fujikuroi species complex contains the highest number of species, of which F. proliferatum and F. verticillioides are the most relevant, as is the case in Mexico [20, 26, 27].

Reports of FDSC infections are less frequent and may cause superficial or disseminated infections [22, 34, 35]. The epidemiology of the infections caused by this complex is unknown because there are few reports with molecular identification. To our knowledge, the species that we founded has not been reported to be associated with human infections; one of this isolate, given the low percentages of similarity (90%) with Mycobank and GenBank sequences (98%), probably represents a new species closely related to F. dimerum SC. The advantages of molecular identification through sequencing of highly discriminatory targets such as EF1α or rpb2 and comparing to specific Fusarium MLST or Fusarium ID databases is recommended to achieve species-level identification [36]. To confirm whether this is in fact a novel species multilocus analysis suggested in Fusarium MLST is pending [37].

Fusarium species show elevated MICs to most antifungals with differences between SCs, as previously described FSSC and FDSC had the highest VOR MICs compared to other species complexes, with the lowest MICs in FOSC and FFSC [13]. AMB was the most active antifungal, in agreement with previous reports [13, 28, 38].

To date, there are no clinical breakpoints but ECVs for FSSC, FOSC and F. verticillioides have been established which may aid identifying those isolates that are most likely to contain acquired molecular mutations that confer resistance (non-wild-type isolates). In this report, two F. verticillioides showed POS MICs above the ECV and one for VOR. These differences in susceptibility between species within the same complex reinforce the need for identification at the species or complex level. Antifungal activity against the probable new species was consistent with the proximity to F. dimerum.

Currently, there are no ECVs for ISA. Broutin et al. found that among 75 Fusarium isolates, antifungal activity was generally limited, with an MIC50 of 16 μg/mL, without significant differences between SCs. Other studies suggest poor in vitro activity [26, 39], despite limited clinical data, this agent is not a recommended treatment option.

Poor outcomes in invasive disease are frequent, with a 90-day survival of 45%; despite elevated MICs for most antifungals, recent guidelines for the treatment of fusariosis strongly recommend combination treatment with lipid formulations of AMB and VOR [40]. Also, AST is recommended to guide the choice of antifungal treatment. A recent multicentre retrospective study collected data from 88 patients with invasive fusariosis and did not find a correlation between MIC and outcome [7]. Instead, persistent neutropenia and receipt of corticosteroids were strong predictors of 6-week mortality [7]. Still, AST is relevant for epidemiological purposes.

Additionally, we found cases in individuals with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease, a condition not frequently described in fusariosis. This finding should be studied prospectively due to the high prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM in our population [41].

We recognise several limitations regarding a limited number of isolates from a single centre. However, this study sums to recent studies from Mexico, to fully characterise molecular species distribution in our region, where most data come from Brazil.

Invasive fusariosis is an emergent infection recently causing outbreaks in our region, which a limited antifungal armamentarium is available.

5 Conclusions

We performed molecular identification and AST of 35 clinical isolates of Fusarium. F. petroliphilum from the FSSC was the most frequent species. Elevated mortality and MICs for all antifungals tested were found, with higher MIC50 among FSSC compared to FOSC or FFSC.

Author Contributions

Carla M. Román-Montes: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Fernanda González-Lara: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Paulette Diaz-Lomelí: data curation, methodology, software. Axel Cervantes-Sanchez: data curation, methodology. Andrea Rangel-Cordero: data curation. José Sifuentes-Osornio: supervision, validation, writing – review and editing. Alfredo Ponce-de-León: supervision, writing – review and editing, validation, funding acquisition, resources. Areli Martínez-Gamboa: conceptualization, supervision, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, visualization, project administration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to María Guadalupe Frías-De-León from the Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad Ixtapaluca, State of Mexico, for technical support in submitting the sequences to Genbank.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.