Is English the Culprit? Longitudinal Associations Between Students’ Value Beliefs in English, German, and French in Multilingual Switzerland

Abstract

Motivational interactions during multiple language learning have been largely neglected in language motivation research. To fill this gap, we investigate longitudinal relations between Swiss German students’ value beliefs in English, French, and German in upper secondary schools and whether there are differences in motivational development between multilingual and monolingual students. Multivariate latent growth modeling was used to analyze data from 850 students (Mage = 15.61 years, SD = .62; 54% female) gathered yearly from Grades 9 to 11. Results suggest an interference between students’ value beliefs in English and the other 2 languages. Students who reported higher value beliefs in English in Grade 9 showed steeper decreases in their value beliefs for French and German from Grades 9 to 11. However, stronger increases in English value beliefs over time were associated with stronger increases in French and German value beliefs. Moreover, while multilingual students reported higher initial value beliefs in French and English, they also showed steeper decreases in French and English value beliefs over time compared to their monolingual peers. Findings are discussed in relation to their implications for teaching practice and future research directions.

BEING FLUENT IN MORE THAN ONE foreign language has become a major educational goal in Europe (Council of Europe, 2019; European Commission, 2004). However, teaching foreign languages in conjunction with English as a global foreign language seems to pose a challenge, since the simultaneous learning of English is believed to lead to negative interferences with students’ motivation to learn other languages (Ushioda, 2017). This appears to be a general European phenomenon (Duff, 2017), as cross-sectional research from several countries has repeatedly shown that students usually report lower value beliefs and motivation to learn languages other than English (LOTEs; Busse, 2017; Dörnyei et al., 2006; Lasagabaster, 2017). Still less is known about longitudinal relations between students’ motivation for several languages. Moreover, the motivational development might not be the same for all students. Previous studies indicate systematic individual differences in students’ motivational beliefs depending, for instance, on their gender, language background (Brühwiler & Le Pape Racine, 2017; Rjosk et al., 2015; Walter & Taskinen, 2008), or experience with learning several languages at home (Dincer, 2018; Lanvers et al., 2019; Thompson & Lee, 2018).

In order to expand previous research on language motivation, the present study focuses on upper secondary students’ academic language learning in Switzerland, a historically multilingual country. This context provides a unique opportunity to understand how students’ prior linguistic knowledge (e.g., growing up with more than one home language) may be related to their motivation to learn several languages. To explore the longitudinal relationship between students’ motivation for several languages in more depth, this study draws on the concept of value beliefs, which refer to the value students attribute to doing a certain task or activity (Wigfield & Eccles, 2002) and are particularly important for predicting students’ language learning motivation (Loh, 2019). First, we investigate the longitudinal relations between Swiss German students’ value beliefs in English (a foreign language), French (a foreign but national language), and German (the native language, as data were obtained in German-speaking Switzerland) from Grades 9 to 11. Second, we explore potential relations between students’ development of value beliefs in the three language subjects and their linguistic background (monolingual vs. multilingual).

VALUE BELIEFS AND LANGUAGE LEARNING

Understanding students’ motivation for learning new languages has been a concern of teachers and researchers in psychology and applied linguistics for more than five decades (see Al–Hoorie & MacIntyre, 2020; Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Mercer et al., 2012, for reviews). The most common motivation models used are the socioeducational model (Gardner, 1985), self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2017), the second language (L2) motivational self-system (Dörnyei, 2005, 2009), and expectancy-value theory (EVT; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). These models have distinct characteristics in describing language motivation but they all share some commonalities, in that they usually differentiate between motivational beliefs arising from within individuals or being influenced from outside (e.g., by parents). For instance, EVT posits that students’ value beliefs (beliefs about the value of engaging in a task) can predict how they will learn (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Some of these value beliefs, such as the intrinsic value (pertaining to personal interest or enjoyment) or the attainment value (pertaining to the personal importance of doing well), share some intrinsic aspects, which are generally argued to be particularly important in language learning (see Loh, 2019; Noels, 2009). If students see the value in an activity, they are more likely to engage in learning and to use effective learning strategies (Wigfield & Cambria, 2010). L2 studies that have included EVT-type constructs indicate that students’ value beliefs play a positive role for their persistence and intention to continue learning a new language (e.g., MacIntyre & Blackie, 2012) as well as for their achievement (e.g., Nagle, 2021; Trautwein et al., 2012).

Regarding the development of value beliefs over time, a large body of EVT-based work has documented an average decline in students’ value beliefs across academic domains, especially throughout late childhood and adolescence (see Wigfield & Eccles, 2020). Moreover, some studies were able to show that longitudinal relations between value facets (e.g., intrinsic and attainment value) differ between academic subjects (see Arens et al., 2019). Nonetheless, it is still an understudied issue in educational research whether and how certain value beliefs may also interact with each other over time and across several language subjects.

SIMULTANEOUS LANGUAGE LEARNING AND MOTIVATIONAL INTERFERENCE OF ENGLISH

Research that explores students’ motivation for learning multiple languages often points to the existence of competing motivational dispositions. Specifically, in nonanglophone European contexts, it is usually the case that the majority of students will already have started learning English as an L2, with the other languages learned thus assuming third language (L3) status. These coexisting constituent languages within learners’ linguistic repertoires are believed to complement each other (Jessner, 2008) but can also interfere and compete both at a crosslinguistic level in terms of psychotypology and at an affective level at play in the motivation process (Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005).

Indeed, there is a growing concern that motivation for learning LOTEs is suffering when individuals are also simultaneously learning English as a foreign language (Dörnyei & Al–Hoorie, 2017; Huang & Feng, 2019). Studies from Europe have regularly suggested that learning English can negatively affect individuals’ motivation to learn LOTEs (Busse, 2017; Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005; Csizér & Lukács, 2010; Dörnyei et al., 2006; Lasagabaster, 2017). Some early evidence comes from research by Dörnyei and colleagues (2006), who conducted a large-scale longitudinal investigation of language learning motivation in Hungary involving more than 13,000 learners over a period of 12 years and focusing on five languages (English, German, French, Italian, and Russian). Their results revealed that students’ motivation was unevenly distributed, with English potentially negatively influencing other languages. However, their study did not closely investigate longitudinal associations and possible interactions between the languages. Similarly, findings from cross-sectional research by Henry (2010, 2011) with pupils in Sweden also found that English was negatively related to students’ motivation to study Spanish, French, and German during simultaneous language learning. He interpreted the findings as showing that learners of several languages seem to possess separate self-concepts and that the English self-concept functions as a normative referent for the other language self-concepts. Finally, in bilingual Belgium, findings from Dewaele (2005) suggest that learners’ narrow focus on the instrumentality of language learning could also play a role in the motivation process. Dewaele surveyed Flemish high school students and found that they considered English a “cool” language (p. 130) and were more negative toward French because of the fraught relationship with that language community in Belgium.

Overall, these findings and considerations imply that there might be several reasons why motivation to learn English could lead to negative interferences. Students’ limited motivational resources and their limited contact with LOTEs during the process of learning might lead to a preference for English (Henry, 2011). In addition, the surging instrumental value of learning English during the past decades might prompt students to perceive learning English as an investment in their future social and professional identities, disadvantaging motivation for LOTEs (Ushioda, 2017). Nevertheless, as the past studies were mainly cross-sectional, it is still unclear whether the presumed negative influence of English persists over the school years. In fact, there is some evidence indicating that students can show motivation for LOTEs while also learning English (Zaragoza, 2011). Recent findings by Siridetkoon and Dewaele (2018) suggest that in some cases, learners may become motivated for LOTEs exactly because everybody seems to know English. Therefore, instead of seeing motivations for different languages as separate systems, the focus on how these systems interact or coexist over time would generate more insight into the topic.

MULTILINGUALISM AND LANGUAGE MOTIVATION

Another important but less investigated aspect is whether knowing multiple languages might play a role in students’ motivational development in school. Research from the L2 acquisition literature has pointed toward a positive role of multilingualism in learning additional languages, arguing that multilingual learners have a broader linguistic repertoire and mnemonic strategies that they can use for learning (Cenoz, 2013; Cummins, 2007; Kemp, 2007). Moreover, Thompson and colleagues (Thompson, 2013; Thompson & Erdil–Moody, 2016) emphasized that the languages learned in the past play a positive role in subsequent language learning and expand multilinguals’ ability to learn languages.

Some literature on motivation in language learning suggests that multilingualism could constitute a source of motivation (Busse, 2017; Dörnyei & Al–Hoorie, 2017; Lasagabaster, 2017; Ushioda, 2017). Henry (2017), for example, argued that in a situation where two or more additional languages are learned or acquired simultaneously, individuals can develop an ideal multilingual self, and that this may positively influence their motivation to learn multiple languages. Indeed, some initial empirical evidence seems to support such theorization. Henry and Thorsen (2018) were able to show that students’ ideal multilingual self has an indirect positive effect on intended effort for learning French, German, or Spanish in secondary schools in Sweden. Similarly, Lanvers and colleagues (2019) found a positive effect of linguistic background when conducting an intervention study aimed at raising students’ (age 11–14) awareness of the cognitive benefits of learning multiple languages. They investigated students’ attitudes toward the subject of modern foreign languages in schools in England and Scotland and found that students with multilingual backgrounds (i.e., those whose first language was a LOTE) valued languages as a school subject more than monolingual learners and that this difference increased after the intervention.

While the previous findings suggest that having a multilingual background might be beneficial for students’ motivation to learn additional languages, the relationship between multilingualism and the development of motivation for different language subjects is still unclear, since the available research comes from cross-sectional studies and has only been conducted in traditionally monolingual contexts (Henry, 2010; Thompson & Erdil–Moody, 2016; Thompson & Lee, 2018). In addition, there was no distinction between different language subjects (Lanvers et al., 2019). Therefore, it remains an open question whether multilingual and monolingual students differ in their motivation to learn multiple languages.

LANGUAGE EDUCATION AND MOTIVATION IN SWITZERLAND

The Swiss context provides a unique opportunity to explore the development and interconnectedness of motivation for several languages within a rather monolingually oriented educational system (Busch, 2011). Switzerland is a historically multilingual country, mainly due to immigration and professional mobility, and has not one but four national languages spoken regionally (German, French, Italian, and Romansh). Hence, there is naturally a higher proportion of citizens who grow up with at least more than one home language. Learning multiple languages is thus an important political and educational goal, and the coordination of language teaching is particularly important. In 2004, the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education (EDK) adopted a national strategy for the development of language teaching, which provides that a second additional foreign language should already be learned in elementary school (EDK, 2004). The cantons were advised that the foreign languages taught should be a second national language as well as English, given the political and cultural importance of the four national languages but also the increasing global importance of English. However, it remains ultimately left up to the 26 cantons to decide which languages are to be taught and which foreign language comes first in elementary school. Moreover, even though the curriculum suggests different ways of connecting the teaching and learning of different languages, all languages are represented as separate units and academic subject domains, indicating a monolingual norm at school (Lundberg, 2019; Schädlich, 2020).

Due to the different linguistic conditions and the freedoms that each Swiss canton has, different language teaching models exist throughout the country. The German-speaking cantons of central Switzerland, where the present study was carried out, have opted to start with English as the first foreign language, thus giving it preference over the national language French. Accordingly, Swiss German students usually start to learn English at age 9 (Grade 3) and French at age 11 (Grade 5) in primary education. While opponents saw the decision as a threat to the unity of Switzerland, supporters of the move pointed out that English is more useful in the world and added that since motivation is an important factor in language learning, students are likely to learn English more successfully than they do French.

Since then, some studies from the German-speaking part of Switzerland looking into students’ motivation for English and French have indicated that younger students’ (9–12 years) motivation in English was not significantly different from their French motivation (e.g., Heinzmann, 2010; Hoti & Werlen, 2009), while other studies found a preference for English over French (e.g., Heinzmann, 2013). Regarding older students (12–14 years) in Switzerland, Peyer and colleagues (2016) found that at the grade transition, intrinsic motivation for English remained stable while it decreased for French. Importantly, some studies also found significant differences between students’ motivation in English and French, depending on their linguistic background (if they are monolingual or multilingual). For instance, Heinzmann (2013) found that multilingual children (9–12 years) were more motivated to learn French. For English, there was no effect of linguistic background, which Heinzmann (2013) attributed to both monolingual and multilingual children being aware of the importance of English in the world. In contrast, Brühwiler and Le Pape Racin (2017) found that children (12–13 years) from families in which languages other than German, English, or French were spoken at home showed higher intrinsic motivation in both English and French compared to children that grew up monolingual.

In sum, the cross-sectional evidence so far suggests that older students may prefer English over French in school; yet it is an open question whether there are longitudinal relations between students’ motivational beliefs in several languages and if the motivational development also differs for older students growing up with more than one home language.

PRESENT STUDY

- RQ1. What is the relation between students’ value beliefs in English, French, and German from 9th to 11th grade?

- RQ1a. How is students’ initial level of value beliefs in English associated with the development of value beliefs in French and German?

- RQ1b. How is students’ development of value beliefs in English related to the development of value beliefs in French and German?

- RQ2. Is the development of value beliefs for the three language subjects the same for multilingual and monolingual students?

Here, we conceptualized multilingualism in a broad and inclusive sense that refers to growing up with more than one home language (see Aronin & Singleton, 2012). Following previous research (e.g., Henry & Thorsen, 2018; Lanvers et al., 2019), we assumed that multilingual students would report higher value beliefs in French and German in Grade 9 compared to monolingual students. Also, we hypothesized that monolingual students would experience a steeper decrease in their value beliefs in French and German compared to multilingual students. Considering the special global status of English, we left it an open question whether multilinguals’ development of motivation for English would differ from that of their monolingual peers.

METHOD

Data and Participants

The RQs were answered through reanalysis of data from a large-scale longitudinal study conducted between 2012 (Grade 9) and 2014 (Grade 11) in the German-speaking part of Switzerland that aimed at investigating students’ cognition, motivation, and emotions in several academic subjects. A total of 915 students participated in the first assessment but one school had to be excluded because the school administration decided to stop their participation after the first assessment due to organizational reasons. The final sample consisted of 850 Swiss students (Mage = 15.61 years in Grade 9, SD = .38; 54% female) from 37 different classes and 7 schools. The majority of the students reported having been born in Switzerland (90.7%). The study protocols were in compliance with the Ethical Principles of the WMA Declaration of Helsinki, and they were approved by the institutional review board of the university carrying out the study as well as all school principals and participating students.

Measures

The assessments were carried out by trained research assistants in schools using a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Information on students’ linguistic background was gathered in Grade 9. Value beliefs in the three language subjects were assessed at each of the three measurement points (Grades 9, 10, and 11).

Linguistic Background

Students were asked to indicate their native language and whether they grew up monolingual, bilingual, or trilingual. If they reported being bilingual or trilingual, they were also asked to say which other languages they were fluent in. Only about 3% of students indicated being fluent in three languages. We categorized students as being multilingual if they reported growing up with more than one language. Hence, we only differentiated between students being mono- versus multilingual (dummy coding: monolingual = 0, multilingual = 1). Overall, German was the native language1 of about 86% of the students; 14% of the students reported other languages as native tongues, of which about 1% reported French (national language) and less than 1% reported Italian (national language) as their native language. Multilingual students (n = 178) mostly grew up with German (60%) as their first native language. Of the multilingual students, 5% reported another national language as their first native language (French, Italian, or Romansh), and about 35% had native proficiency in one of the following languages spoken in their families: Albanian, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, English, Kurdish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovenian, Spanish, Turkish, and Vietnamese. Our sample thus comprised a varied set of languages.

Value Beliefs

This construct asked for students’ personal importance attributed to a language subject and was measured with three items using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly) for each of the language subjects (e.g., “[French] is very important to me regardless of the grade,” “I consider [English] to be very important,” “[German] is my favourite academic subject”). The scales were adapted from Pekrun et al.’s (2007) longitudinal Project for the Analysis of Learning and Achievement in Mathematics (PALMA) study. We used McDonald's omega (ω), a more robust and precise measure than Cronbach's alpha, to estimate internal consistency (Dunn et al., 2014; McNeish, 2018). The coefficients showed acceptable internal consistency (.75–.87) at all three measurement points (see Table 1).

| Variable | N | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 850 | |||||

| Linguistic background | 720 | |||||

| Value beliefs—English (T1) | 745 | 3.82 | .56 | −.65 | .36 | .75 |

| Value beliefs—English (T2) | 658 | 3.83 | .56 | −.77 | .84 | .74 |

| Value beliefs—English (T3) | 661 | 3.87 | .50 | −.86 | .96 | .75 |

| Value beliefs—French (T1) | 749 | 2.91 | 1.06 | −.02 | −.74 | .86 |

| Value beliefs—French (T2) | 651 | 2.84 | 1.04 | −.09 | −.77 | .84 |

| Value beliefs—French (T3) | 656 | 2.68 | 1.10 | .13 | −.87 | .87 |

| Value beliefs—German (T1) | 745 | 3.09 | .79 | −.10 | −.38 | .80 |

| Value beliefs—German (T2) | 658 | 2.95 | .93 | −.10 | −.56 | .84 |

| Value beliefs—German (T3) | 664 | 2.96 | .91 | −.05 | −.53 | .84 |

- Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; ω = McDonald's omega; T1 = Grade 9; T2 = Grade 10; T3 = Grade 11.

Analytical Approach

Analysis of Measurement Invariance

First, we estimated multigroup confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to determine whether the measurement structure was consistent across academic subjects (English, French, and German), time (Grades 9–11), and groups (monolingual and multilingual). A baseline model was estimated in which factor loadings and item intercepts were allowed to freely vary across academic subjects and time to check whether the same factorial structure (configural invariance) could be confirmed. Then, the factor loadings of each item (metric invariance) and the intercepts (scalar invariance) were fixed to equality (van de Schoot et al., 2012). To judge overall model fit, we used cut-offs suggested by Hu & Bentler (1999) for the model fit indices root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; <.09 for moderate fit, <.05 for good fit), comparative fit index (CFI; >.90 for moderate fit, >.95 for good fit), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; <.11 for moderate fit, <.07 for good fit), and we applied the suggestions by Chen (2007) to judge measurement invariance. Chi-square statistic was not used as a sole indicator of model fit as it can be sensitive to a large sample size (Hooper et al., 2008).

Multivariate Latent Growth Models

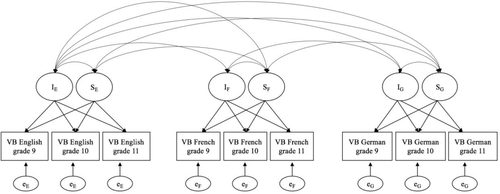

To answer the two RQs, multivariate latent growth modeling (LGM) was used. The advantage of multivariate LGM is that it allows for analysis of simultaneous relations between students’ motivational beliefs in the three language subjects and differences among students in their motivational development over time. Two growth parameters were used to characterize students’ individual paths: (a) an initial (baseline) parameter (= intercept), and (b) a linear growth rate parameter (= slope). Both these parameters are viewed as factors that vary between students. In this study, six latent factors were assumed: an intercept and a slope for value beliefs in English, French, and German. Figure 1 gives the path diagram for the proposed multivariate LGM.

Path Diagram for the Multivariate Latent Growth Model

Note. I = intercept; S = slope; VB = value beliefs; E = English, F = French, G = German. The double-headed arrows indicate the correlations between intercepts (baseline) and slopes (rate of change) for value beliefs for English, French, and German.

The analyses were conducted in three steps using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The TYPE = COMPLEX option was used to account for the nested structure of the data (students nested in classes) and the resulting nonindependence of individual scores (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). First, we tested univariate latent growth models separately for each academic subject. Intercept and linear slope were estimated to test students’ initial level of value beliefs and constant rate of change. We only analyzed linear models as it was not possible to fit a quadratic latent curve model to the data since this cannot be done with three measurement points. Nevertheless, preliminary analyses suggested a linear development in the mean scores of value beliefs in the three language subjects across Grades 9 to 11.

Second, a multivariate LGM was used to answer the first RQ regarding simultaneous longitudinal associations in value beliefs among the three language subjects. Specifically, we looked at three types of relations between parameters in the model: (a) the intercept–intercept correlation, which for instance, can indicate to what extent the baseline mean of value beliefs in English in Grade 9 is associated with the baseline means in French and German, (b) the intercept–slope correlation, which shows how the baseline means in value beliefs in English in Grade 9 are related to decreases or increases in value beliefs in French and German from Grades 9 to 11, and finally (c) the slope–slope correlation, which indicates how the change in value beliefs in English relates to changes in value beliefs in French and German from Grades 9 to 11.

Finally, to answer the second RQ, we examined whether the growth trajectories in value beliefs differed between multilingual and monolingual students. A dummy coded variable, linguistic background, was entered as a time-invariant predictor of the intercepts and slopes, and gender was included as a control variable. For the sake of clarity, only estimates of the final multivariate model are provided. Missing data were estimated through the full information maximum likelihood method.

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics and the correlations among variables included in the analyses are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Table 3 shows the results of the measurement invariance testing. The CFA models suggested that value showed strict measurement invariance. In other words, we found a high structural similarity in the construct across the three language subjects (English, French, and German), time (Grades 9–11), and groups (monolingual and multilingual). This allowed us to statistically compare the mean levels and changes across language subjects and time simultaneously.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gendera | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Linguistic backgroundb | .02 | — | |||||||||

| 3. Value beliefs—English (T1) | −.11** | .07* | — | ||||||||

| 4. Value beliefs—English (T2) | −.14** | .06 | .61** | – | |||||||

| 5. Value beliefs—English (T3) | −.11** | −.01 | .52** | .62** | — | ||||||

| 6. Value beliefs—French (T1) | −.30** | .08* | .27** | .19** | .14** | — | |||||

| 7. Value beliefs—French (T2) | −.36** | .05 | .18** | .19** | .14** | .71** | — | ||||

| 8. Value beliefs—French (T3) | −.27** | −.05 | .22** | .20** | .20** | .63** | .72** | — | |||

| 9. Value beliefs—German (T1) | −.20** | .04 | .23** | .15** | .12** | .21** | .23** | .22** | — | ||

| 10. Value beliefs—German (T2) | −.26** | .04 | .17** | .25** | .15** | .17** | .29** | .26** | .60** | — | |

| 11. Value beliefs—German (T3) | −.27** | −.03 | .15** | .20** | .27** | .20** | .27** | .32** | .51** | .70** | — |

- Note. T1 = Grade 9; T2 = Grade 10; T3 = Grade 11.

- a Gender: female = 0, male = 1.

- b Linguistic background: monolingual = 0, multilingual = 1.

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 1033.1 | 570 | .05 | .95 | .06 |

| Metric invariancea | 1122.6 | 586 | .05 | .94 | .07 |

| Scalar invarianceb | 1192.7 | 601 | .05 | .94 | .07 |

- Note. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual.

- a Loadings equal across language subjects, time, and groups.

- b Loadings and intercepts equal across language subjects, time, and groups.

The fit indices of the models estimated to answer the first RQ are presented in Table 4. The fit indices of the final multivariate growth curve model with linguistic background as a time-invariant predictor indicated that this model demonstrated a good fit.

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate models | |||||||

| English—linear change | 5.682 | 6 | .00 | 1.00 | .01 | 3985.058 | 3999.130 |

| French—linear change | 15.897 | 6 | .04 | .99 | .01 | 5079.503 | 5093.555 |

| German—linear change | 41.255 | 6 | .08 | .94 | .02 | 4869.957 | 4884.030 |

| Multivariate models | |||||||

| Unconditional model | 41.041 | 18 | .04 | .99 | .02 | 13833.433 | 13889.809 |

| Model with time-invariant predictor | 47.504 | 24 | .03 | .99 | .02 | 15782.194 | 16033.692 |

- Note. CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR-W = standardized root mean square residual–within level; SRMR-B = standardized root mean square residual–between level; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Development of Value Beliefs in English, French, and German

Results revealed significant means of intercepts and slopes of French and German value beliefs (see Table 5). The slope means suggest that value beliefs significantly decreased over the 3 years for French and German, whereas for English, the slope mean suggests an increase in value; however, this change was not statistically significant (p =.437). In addition, there were systematic interindividual differences in students’ initial levels as well as in the development of value beliefs for all three language subjects as indicated by significant variances in intercept and slope means. This means that some students reported higher levels in values than others in Grade 9, and that some students had a higher rate of decline, while some students had lower rates of decline in value beliefs from Grades 9 to 11.

| English | French | German | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | SE | β | p | SE | β | p | SE | |

| Means | |||||||||

| Intercept | 3.819 | <.001 | .047 | 2.908 | <.001 | .053 | 3.073 | <.001 | .060 |

| Slope | .019 | .437 | .025 | −.118 | <.001 | .027 | −.069 | .008 | .024 |

| Linguistic backgrounda on I | .099 | .058 | .052 | .110 | .014 | .045 | .061 | .108 | .038 |

| Linguistic background on S | −.144 | .050 | .073 | −.197 | .019 | .084 | −.069 | .132 | .046 |

| Genderb on I | −.124 | .011 | .049 | −.358 | <.001 | .039 | −.234 | <.001 | .036 |

| Gender on S | −.007 | .917 | .070 | .012 | .873 | .039 | −.094 | .058 | .050 |

| Variances | |||||||||

| Intercept | .410 | <.001 | .047 | .799 | <.001 | .058 | .586 | <.001 | .057 |

| Slope | .060 | .017 | .019 | .081 | .001 | .024 | .149 | <.001 | .024 |

| Paths | |||||||||

| IE → IF | .326 | <.001 | .054 | ||||||

| IE → SF | −.162 | .057 | .089 | ||||||

| IE → IG | .305 | <.001 | .060 | ||||||

| IE → SG | −.129 | .046 | .065 | ||||||

| IF → IG | .225 | <.001 | .048 | ||||||

| IF → SG | −.047 | .408 | .057 | ||||||

| SE → SF | .446 | . 003 | .151 | ||||||

| SE → SG | .483 | <.001 | .106 | ||||||

| SF → SG | .344 | .003 | .116 | ||||||

- Note. I = intercept, S = slope; E = English, F = French, G = German.

- a Linguistic background: monolingual = 0, multilingual = 1.

- b Gender: female = 0, male = 1.

Longitudinal Associations Between Value Beliefs in English, French, and German

With regard to the first RQ investigating longitudinal relations between students’ value beliefs for the three languages, the correlation between the three intercepts indicated significant positive relations between students’ initial levels of value beliefs for English, French, and German (see Table 5). This means that students reporting higher value beliefs in English in Grade 9 also reported higher initial value beliefs in French and German. To see how students’ initial level of value beliefs in English was associated with the development of value beliefs in the other two language subjects, we examined the relation between the English intercept and the slopes for French and German. Results revealed a marginally significant negative relation between English intercept and French slope, β = −.162, p = .057, and a significant negative relation between English intercept and German slope, β = −.129, p = .046. These results suggest that students who reported higher value beliefs in English in Grade 9 tended to show steeper decreases in their value beliefs in French and German from Grades 9 to 11.

To see how students’ development of value beliefs in English related to the development of value beliefs in French and German, we examined the relation between the three slopes (see lower part of Table 5). The estimates were positive and significant, suggesting that stronger increases in English value beliefs were associated with stronger increases in French, β = .446, p = .003, and German, β = .483, p < .001. In addition, students showing a stronger increase in French value beliefs tended to also show a stronger increase in German, β = .344, p = .003.

Differences in Development Between Monolingual and Multilingual Students

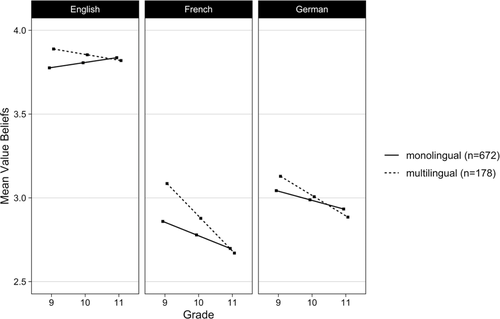

Regarding the second RQ investigating differences in the development of value beliefs for the three language subjects between monolingual and multilingual students, results in Table 5 revealed that linguistic background was a (marginally) significant positive predictor of value beliefs for foreign languages in Grade 9: French, β = .110, p = .014; English, β = .099, p = .058. This indicates that multilingual students reported significantly higher initial levels of value beliefs in French and English. However, linguistic background was also a significant predictor of the rate of decline in value beliefs in French and English. This means that multilingual students’ value beliefs decreased significantly faster relative to that of their monolingual peers (approximately .11 points on the Likert scale for French and .14 points for English). The estimated average trajectories are illustrated in Figure 2. Particularly noteworthy is the opposite developmental pattern in English as it suggests that compared to the decreasing trend for multilingual students, monolingual students seemed to show a slight increase in value beliefs from Grades 9 to 11.

DISCUSSION

This study used a longitudinal perspective to explore associations in students’ value beliefs in English, French, and German over the course of 3 years and to examine whether value beliefs develop differently for multilingual and monolingual students. Results indicated that, on average, students’ value beliefs for French and German decreased from Grades 9 to 11. Although the data collection was carried out in Switzerland, which has a rather specific situation concerning multilingualism (four national languages), these findings may well provide indications for other countries that strive for multiple language acquisition at school.

In line with previous motivational research (Busse, 2017; Dörnyei et al., 2006) and EVT-based work (see Wigfield & Eccles, 2020), we found a significant average decline in Swiss students’ value beliefs in French and German over time. However, the data also suggest a clear preference for English over French and German. This finding contributes to the literature investigating language motivation in educational settings by showing that even in a historically multilingual country that actively encourages multiple language learning, the subject of English enjoys a special status among students.

Looking at the cross-sectional relations among the baseline (intercept) means of the three language subjects, the analyses indicated a positive relation, suggesting that students who reported higher value beliefs in English in Grade 9 also reported higher value beliefs in French and German. However, when looking at the relation among the three language subjects longitudinally, we found that students who reported higher value beliefs in English in Grade 9 showed steeper decreases in French and German value beliefs over time. At the same time, the analyses also revealed that steeper increases in English value beliefs were associated with steeper increases in value beliefs in the other two subjects. These results suggest that students’ value beliefs for several language subjects can interact with each other over time, partially supporting previous research that argued for longitudinal relations in motivation between different languages (Dörnyei & Al–Hoorie, 2017; Ushioda, 2017; Ushioda & Dörnyei, 2017).

Based on past theoretical and empirical research (Brühwiler & Le Pape Racine, 2017; Henry, 2010; Lanvers et al., 2019) suggesting that multilingual students might be more motivated to learn languages, we further investigated differences in motivational development across the three language subjects depending on whether students had grown up as monolingual or multilingual. Partially confirming our expectations, we found that multilingual students reported higher value beliefs in French and in English in Grade 9. Hence, it seems that students growing up with more than one language at home may initially be more motivated to learn additional foreign languages. A possible explanation for why we found no initial significant differences between monolingual and multilingual students in German might be that German is the official language in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, in which the study was conducted, and its necessity in everyday life may be more apparent to students. French, however, might be regarded as less relevant by monolingual German-speaking students, since they will rarely need to use it outside school if they remain in the German-speaking region.

Importantly, despite the initial positive motivational advantage of multilingual students, our findings also showed that students’ linguistic background may not be enough to maintain a high level of value beliefs over the school years. Contrary to our expectations, we found that multilingual students reported steeper declines in value beliefs in French and English compared to their monolingual peers. One possible explanation for this might be that since multilingual students had started with higher initial levels of motivation in French, they consequently had higher expectations of the subject that were perhaps not met in the classroom. Moreover, it is important to note that the average trajectories of value beliefs in English showed opposite patterns, suggesting that while value beliefs in English decreased for multilingual students, they actually increased for monolingual students. This opposite development could be related to the fact that multilingual students have a larger linguistic repertoire that could be relevant for them later in life, and with increasing age they become more aware of this advantage, possibly leading to the slight decline in motivational beliefs in English compared to their monolingual peers. The increasing trend in English motivational beliefs for monolingual students could be related to the finding that as students age, the attainment value (importance) generally becomes more augmented (Wigfield et al., 2009). By Grade 11, the students were approaching the final phase of their secondary school education. This is a time when students generally start to think about future job possibilities. In the German-speaking part of Switzerland, good English skills are increasingly required or even assumed for job opportunities, and this awareness might have led to an increase in the subjective importance of English for monolingual students. Nonetheless, more research is necessary to possibly replicate and understand the opposite developmental trend between monolingual and multilingual students identified in our data.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting its findings. First, because of the study design, we cannot draw conclusions regarding the directionality or causal relationships between the study variables. However, our approach does provide an idea of the pattern of change and the associations between the rates of change in value beliefs in the three language subjects. In addition, the present study only addressed students’ value beliefs pertaining to the personal importance they attributed to each language subject. This taps into just one aspect of language learning motivation; therefore, the conclusions that can be drawn about students’ global language learning motivation need to be treated with caution.

Moreover, we did not consider the degree of homogeneity in language backgrounds of the multilingual students as this was difficult to model and it would have made estimates imprecise. Yet, there is some evidence that students with a migrant background might show more motivation for certain language subjects (see Rjosk et al., 2015) and, if statistically feasible, this should be considered in future investigations.

Finally, due to the computational complexity of the models, we only looked into average differences in motivational development between monolingual and multilingual students. In other words, we still do not know whether there are any differences in the association between the changes in the three language subjects depending on students’ linguistic background. Nevertheless, our results suggest students’ prior linguistic experiences play an important role in their motivational development and should therefore be considered in future research.

Implications for Practice and Research

This study set out to examine longitudinal motivational influences in language learning when students learn English as foreign language at the same time. Our results suggest that the development of motivation for several language subjects is interrelated and that students’ initial higher valuing of English might have led to some declines in their value beliefs for the other languages over time. This partially corroborates various concerns raised in the literature about English being seen as a potential “culprit” (see Ushioda, 2017). Nevertheless, the analyses further show that increases in students’ value beliefs in English are associated with increases in French and German. For educational practice, these results suggest that teachers of LOTEs might face the challenge of having to “compete” with students’ prior preference for English at first. However, it also seems that increasing motivation in English can lead to increases in motivation in other language subjects. Therefore, our study underlines the importance for more collaboration between language educators and language teachers to consider the interrelatedness of student motivation for different language subjects and to find solutions to minimize the potentially growing imbalance between languages in educational settings (Busse, 2017; Ushioda, 2017). For instance, teachers could address the importance of knowing multiple languages, highlight connections and differences, and work in a more integrative way.

For research practice, the longitudinal associations identified underscore the relevance of investigating students’ motivational development jointly across languages and support assumptions about interrelated systems that are simultaneously constituents within a higher-level motivational system (Henry, 2017). Another noteworthy finding of this study was that students growing up with more than one home language seemed to report a decline in value beliefs pertaining to the personal importance they attributed to the three language subjects, highlighting the need for more research that investigates multilingual students’ needs and expectations in language lessons. However, since our study considered only one facet of learning motivation, these findings need to be treated with caution, and future studies should examine more aspects of language learning motivation in multilingual students before drawing any conclusions. Our results only suggest that growing up with more than one home language may not be enough to prevent declines in some aspects of motivation. Here, it is also important to note that even though multilingual students’ value beliefs showed a decreasing trend, the fact that the reported values were at or slightly above the midpoint of the scale seems to suggest that multilingual students still attributed moderate importance to the language subjects in Grade 11.

Previous research has argued that developing a multilingual self may act as a protection against motivational decline (Henry, 2017; Henry & Thorsen, 2018; Ushioda, 2017); therefore, more research is needed to understand whether students growing up with more than one home language develop a multilingual self and whether harnessing it can help maintain motivation for learning multiple languages.

Further, it would also be interesting to look into possible peer influences on students’ language motivation. In the present study, we noticed a convergent motivational development from Grades 9 to 11. Even though multilingual students started with higher value beliefs, by Grade 11, they reported lower and similar levels of value beliefs as their monolingual peers. This convergence could be related to some in-class motivational processes. For instance, Tanaka (2017) showed that demotivated peers can have a negative influence on students’ motivation. Investigating such peer influences on language motivation could be a useful addition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a scholarship of the Forschungskredit of the University of Zurich (grant number FK19-059) and by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 100014_131713/1).

Open access funding provided by Universitat Zurich.