Hepatitis E, the neglected one

Abstract

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is a worldwide disease. It is the first cause of acute viral hepatitis in the world with an estimated 20 million cases every year and 56 000 deaths. In developing countries, hepatitis E is a waterborne infection. In these countries, HEV genotypes 1 and 2 cause large outbreaks and affect young subjects with a significant mortality rate in pregnant women and patients with cirrhosis. In the developed countries, HEV genotypes 3 and 4 are responsible for autochthonous, sporadic hepatitis and transmission is zoonotic. HEV can cause neurological disorders and in immunocompromised patients, chronic infections. The progression of acute hepatitis E is most often mild and resolves spontaneously. Diagnostic tools include anti-HEV IgM antibodies in serum and/or viral RNA in the blood or stools by PCR. Ribavirin is used to treat chronic infection. A vaccine has been developed in China.

Abbreviations

-

- GBS

-

- Guillain–Barré syndromes

-

- HEV

-

- hepatitis E virus

-

- ORFs

-

- Open reading frames

Key points

- In developed countries, there is a risk of ‘zoonotic’ transmission, in particular by ingestion of contaminated food, mostly pork, with hepatitis E virus (HEV) genotypes 3 or 4.

- There are severe forms of acute hepatitis E in patients with cirrhosis and the elderly.

- HEV infection can be associated with neurological signs including Parsonage Turner syndrome, Guillain–Barré syndrome, meningoradiculitis and mononeuropathy multiplex.

- HEV may cause chronic hepatitis in immunocompromised patients. In these patients, diagnosis is based on the detection of viral RNA in the serum and/or faeces. They should be treated with ribavirin for 3 months.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) was discovered by immune electron microscopy in 1983 by Dr. Balayan, who was investigating an outbreak of unexplained hepatitis in Russian soldiers stationed in Afghanistan 1. The hepatitis E genome was sequenced in 1991. The same year, a test was developed for detecting anti-HEV antibodies 2. The purpose of this paper is to review the virology, epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment of hepatitis E.

Background and virology

Hepatitis E virus is a small non-enveloped virus of about 30 nm. It has a positive sense, single-stranded RNA 2.

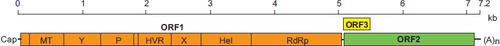

The HEV genome contains three open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1). ORF 1 encodes a non-structural protein which plays a major role in the adaptation of the virus to its host and viral replication. ORF 2 encodes the capsid protein, important in virion assembly and immunogenicity. ORF3 encodes a small protein involved in morphogenesis and release of new virions 2.

The HEV belongs to the new type Hepevirus classified in the family of Hepeviridae (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ICTVdb/) and is currently the only agent. There are four major genotypes of HEV in humans. The first two groups, genotypes 1 (Asia and Africa) and 2 (Mexico and Africa), include strains from areas where the virus is endemic. The strains belonging to genotype 3 have essentially been identified in North America, Europe, South America and Japan. Genotype 4 has mainly been identified in China, Taiwan, Japan and Vietnam, but a few cases have also been reported in Europe. Although an avian HEV was isolated, it has never been isolated in humans.

Epidemiology

Genotypes 1 and 2 are present in developing countries and are transmitted between humans by the faecal–oral route usually via contaminated water. Large epidemics of HEV in these areas are common, mostly during the rainy season, and sporadic cases have also been described.

In the developed countries, genotypes 3 and 4 are transmitted zoonotically from animal reservoirs (mostly pigs and deer).

Acute hepatitis

In the developing countries, epidemics are characterized by a large number of infected individuals and a waterborne source of contamination. For example, the 1978 epidemic in the Kashmir valley in India resulted in 52 000 symptomatic cases and 1700 deaths 3.

Transmission is through direct ingestion of water contaminated by human faeces 1. There is also a risk of maternal–foetal transmission 4 causing neonatal infections. The infection especially affects 15- to 30-year-old men. The mortality rate for adults in an epidemic area is 0.2–4%. It is much higher in patients with chronic liver disease and pregnant women (up to 70% and 25% respectively) 4-6. The risk of maternal complications is increased mainly during the third quarter of pregnancy, in particular for fulminant hepatitis and obstetric complications 5.

There is a risk of ‘zoonotic’ transmission in developed countries (ingestion of contaminated food, mostly pork, with HEV genotype 3 or 4) 7. Parenteral transmission via transfusion of blood products has recently been identified as a new potential mode of contamination 8, 9. In a recent study in England, 1/2848 of a population of blood donors was positive for HEV. Sixty-two contaminated blood products were transfused, leading to HEV infection in 42% of recipients. In the developed countries, acute hepatitis E usually affects middle aged/elderly males (sex ratio = 4/1, median age 55) with excess alcohol consumption 2, 7. The period of incubation is 2–5 weeks. Over 60% of cases are asymptomatic. Jaundice is present in approximately 65% of symptomatic cases. Symptoms are aspecific and common to other viral hepatites: asthenia, diarrhoea, nausea, fever, arthralgia, vomiting and abdominal pain. ALT levels are usually very high (1000–3000 IU/L) but they may be moderately elevated, depending on the time of diagnosis 7. HEV is a self-limiting infection that lasts 4–6 weeks. However, there are severe forms in patients with cirrhosis and in the elderly 10. There are no chronic forms in immunocompetent patients. Cholestatic jaundice can last from several weeks to several months 11. There is no hypertransaminasemia rebound after normalization of liver function tests. Acute hepatitis E can be mistaken for drug-induced hepatitis. Indeed, two studies in patients who had an initial diagnosis of drug-induced hepatitis who were retrospectively tested showed a HEV infection in 3% and 13% respectively 12, 13.

Neurological symptoms

Neurological symptoms have been described for HEV1 and acute and chronic HEV3 infections. An Anglo-French study in Europe in 126 patients identified neurological events in 5.5% of patients with HEV infection 14. Neurological symptoms include neuralgic amyotrophy [Parsonage Turner syndromes (PTS)], Guillain–Barré syndromes (GBS), meningoradiculitis and multiplex mononeuropathies 15. In patients in whom neurological symptoms are predominant, transaminases elevation can be moderate and jaundice may be absent.

The mechanisms causing PTS or GBS in HEV are unknown, but it is probably an immune response induced by the virus. The risk of sequelae is important in these two entities. Meningoradiculitis is probably related to a direct viral effect (the virus is found in the cerebrospinal fluid with lymphocytic meningitis) and patients usually heal without sequelae in several weeks.

Chronic hepatitis

Hepatitis E virus can cause chronic hepatitis in immunocompromised patients such as solid organ transplant patients 16, those undergoing chemotherapy for haematological malignancies 17 and certain patients with HIV 18.

In these cases, acute hepatitis E usually has limited or no symptoms. Liver enzymes are generally moderately elevated and jaundice is rare. The incidence of infection with genotype 3 HEV after organ transplantation was 3.2/100 person-years in the southwest of France 19. Sixty percent of these patients with acute hepatitis E will develop chronic hepatitis 16. In the absence of treatment, progression to cirrhosis can be rapid 20.

Three cases of re-infection in liver transplant patients, who were immunized prior to transplantation with 0.3, 2.1 and 6.2 IgG WHO units/ml, have been described. Therefore, low levels of anti-HEV IgG (<7 WHO units/ml) before transplantation do not seem to protect organ transplant recipients 21.

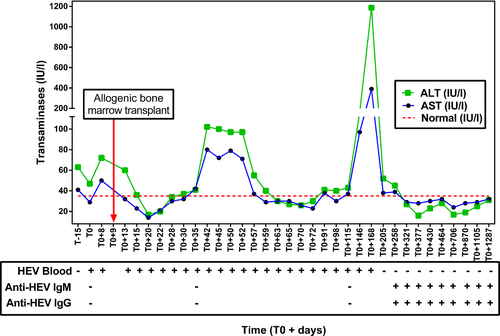

Chronic hepatitis E has also been described in patients with haematological malignancies 17. They are also usually asymptomatic. Transaminases are moderately high at about 500 IU/L. These patients may experience viral clearance over time with a return to normal immunity. This may induce a rebound in transaminases elevation and severe acute hepatitis (Fig. 2) 17.

Chronic hepatitis only occurs in patients with HIV and very low CD4 counts, always below 250/mm3 22. There is a risk of progression to cirrhosis in these cases. In subjects with CD4 > 250 cells/mm3, the risk of severe or fulminant hepatitis is the same as in the general population 23; however, management of HIV during acute hepatitis can be complicated.

A recent French multicentre retrospective study 24 was performed in patients who were receiving immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory rheumatism. Twenty-three cases of acute hepatitis E were reported including 18 patients treated with biotherapies (10 receiving anti-TNF). Evolution of hepatitis E infection was favourable, and no chronic hepatitis or fulminant hepatitis was found.

Diagnosis

Direct diagnosis is based on the detection of viral RNA in the serum and/or faeces. Detection is performed by amplification of the genome in the conserved region overlapping ORF3/ORF2 25. The genotype can be determined to study distribution of the viral strain. Indirect diagnosis is based on the detection of anti-HEV antibodies. IgM, markers of acute infection, appear early and last at least 16 weeks after infection 26. The sensitivity of these tests is excellent in immunocompetent patients (>98%). IgG appear shortly afterwards and last for years. The sensitivity and specificity of commercially available kits (Wantai) for the detection of IgG is good (>93.57% in immunocompetent patients) and for IgM is excellent (>99.5%), 27.

Thus, the diagnosis in immunocompetent patients can be based on serology. In immunocompromised subjects, however, RNA detection is essential.

Treatment

In most cases, HEV infection is a self-limiting disease that does not require treatment. Liver function tests should be monitored in the same manner as any acute viral hepatitis to detect any progression to severe acute hepatitis.

In solid organ transplant recipients, reduction in immunosuppression, including reducing doses of tacrolimus and corticosteroids, induces viral clearance in 30% of cases 28. The standard treatment in patients who do not achieve viral clearance is ribavirin for three months. A sustained virological response (cure) is achieved in more than 70% of cases. Relapse can be retreated with ribavirin for 6 months. The risk factors of relapse are lymphopenia at treatment initiation, HEV RNA in serum after 1 month of treatment, the presence of HEV RNA in the stools at the end of treatment 28 and a decrease in viral load of <0.5 log10 copies/ml on day 7 of treatment.

Chronic or persistent hepatitis in subjects with HIV or who are receiving chemotherapy for haematological malignancies can be treated with ribavirin in the same manner 17. In the developing countries, prevention is based on providing clean drinking water and improving sanitary structures.

In the developed countries, where transmission is mainly because of the ingestion of contaminated food, prevention can be based on conventional recommendations of zoonotic disease transmission. The highest risk products for HEV are undercooked pork products (fresh or dried liver sausage, dry liver, figatelli and liver dumplings) and raw or undercooked products made from wild boar or deer (meat and offal). These products should be avoided especially in the elderly, patients with cirrhosis and immunocompromised patients.

Routine screening of blood donor products is being evaluated. In France, HEV has been screened in plasma donations used in the preparation of fresh frozen plasma treated by solvent detergent since January 2013. It is not systematically screened in all blood donations.

A vaccine was recently approved by the Chinese health authorities: HEV 239 recombinant vaccine (Hecolin; Innovax Biotech Xiamen, Xiamen, China). Its routine use began following a phase III randomized controlled trial against placebo performed between 2007 and 2009 in China 29. More than 100 000 people were vaccinated in a pattern of three injections (0, 1, 6 months). At 4.5 years, acute hepatitis E genotype 1 was found in 53 subjects in the placebo group and 7 in the vaccine group. The efficacy of the vaccine was 86.8%, with good tolerance. This vaccine was approved by the Chinese authorities in healthy adults aged 16–65 years old and pregnant women and has been marketed since October 2012. Long-term persistence of protective immunity has not been evaluated. Moreover, the efficacy of this vaccine in immunocompromised patients must still be determined.

Conclusion

In developed countries, HEV infection should be suspected in any acute hepatitis, especially if it occurs in a patient over 40 years old and is accompanied by neurological symptoms. The source of contamination is usually food especially the ingestion of pork infected with HEV genotype 3. Serology is sufficient for diagnosis in immunocompetent patients but detection of the virus in the blood and/or stool by a molecular biology technique is necessary for immunocompromised patients. Chronic forms of the disease are found in immunocompromised patients with low transaminases and there is a risk of progression to cirrhosis. These patients should be treated with ribavirin.

Acknowledgement

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: The authors do not have any disclosures to report.