A complex scenario of glacial survival in Mediterranean and continental refugia of a temperate continental vole species (Microtus arvalis) in Europe

Abstract

The role of glacial refugia in shaping contemporary species distribution is a long-standing question in phylogeography and evolutionary ecology. Recent studies are questioning previous paradigms on glacial refugia and postglacial recolonization pathways in Europe, and more flexible phylogeographic scenarios have been proposed. We used the widespread common vole Microtus arvalis as a model to investigate the origin, locations of glacial refugia, and dispersal pathways, in the group of “Continental” species in Europe. We used a Bayesian spatiotemporal diffusion analysis (relaxed random walk model) of cytochrome b sequences across the species range, including newly collected individuals from 10 Iberian localities and published sequences from 68 localities across 22 European countries. Our data suggest that the species originated in Central Europe, and we revealed the location of multiple refugia (in both southern peninsulas and continental regions) for this continental model species. Our results confirm the monophyly of Iberian voles and the pre-LGM divergence between Iberian and European voles. We found evidence of restricted postglacial dispersal from refugia in Mediterranean peninsulas. We inferred a complex evolutionary and demographic history of M. arvalis in Europe over the last 50,000 years that does not adequately fit previous glacial refugial scenarios. The phylogeography of M. arvalis provides a paradigm of ice-age survival of a temperate continental species in western and eastern Mediterranean peninsulas (sources of endemism) and multiple continental regions (sources of postglacial spread). Our findings also provide support for a major role of large European river systems in shaping geographic boundaries of M. arvalis in Europe.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is widely understood that Pleistocene glacial refugia are a key factor shaping species evolutionary history and distribution worldwide. However, the number, size, geographic locations, duration of isolation, and role of glacial refugia as a source for postglacial recolonization remain subjects of intense scientific discussions (Fraser, Nikula, Ruzzante, & Waters, 2012; Hewitt, 2000; Schmitt, 2007). Recent studies have challenged traditional views such as temperate species sharing common glacial refugia in the European Mediterranean peninsulas (i.e., Iberia, Italy, and the Balkans), or that these southern refugia are the only sources of postglacial colonization (Stewart, 2003). New and more complex phylogeographic hypotheses/scenarios have been proposed for different biogeographical groups (i.e., Mediterranean, continental, and Arctic/Alpine species, sensu (De Lattin, 1967)), such as the existence of extra-Mediterranean glacial refugia for Mediterranean species (reviewed in Schmitt & Varga, 2012) or steppe-adapted species (Garcia, Alda, et al., 2011; Garcia, Mañosa, et al., 2011), the evidence of cryptic refugia for cold-adapted species (Cruzan & Templeton, 2000; Stewart & Lister, 2001), the occurrence of both “macrorefugia” and “microrefugia” for some taxa (Joger et al., 2007; Rull, 2009, 2010), the existence of “refugia-within-refugia” (Abellán & Svenning, 2014; Gómez & Lunt, 2007), or the consideration of the oceanic-continental gradient as a further biogeographical dimension, in addition to the traditional north–south axis, in defining the location of refugia for some biogeographical groups (Stewart, Lister, Barnes, & Dalén, 2010).

Recent advances in the refugial concept (Provan & Bennett, 2008), and the ample evidence for the individualistic (species- or group-specific) response to extreme climate events (Palmer et al., 2017), have also direct implications for the inferred scenarios of recolonization of many widespread species in the Palaearctic. Accordingly, new paradigms and conceptual frameworks about the extent and pathways of postglacial expansions from these refugia have arisen. Despite the classic scenario in Europe proposes northward routes of colonization from accepted refugia in the three Mediterranean peninsulas (Hewitt, 1996), other studies have suggested a far more complex evolutionary history in which, for some species, Mediterranean peninsulas played a minor role in postglacial colonization (Bilton et al., 1998; Tougard, 2016; Tougard, Renvoisé, Petitjean, & Quéré, 2008). Overall, these investigations stress the need for additional continent-wide specific studies to contrast these models and really understand the complex biogeographical patterns of the European fauna (Schmitt, 2007; Stewart & Lister, 2001), especially in the group of continental species (Schmitt, 2007).

Palearctic mammals (e.g., brown bear Ursus arctos, European hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus, bank vole Myodes glareolus, and European brown hare Lepus europaeus) have proven excellent models for such phylogeographic studies (Hewitt, 1999; Randi, 2007), mostly due to their well-known biology, high population abundance or wide distributions, or relatively low dispersal rate (Beheregaray, 2008). Likewise, the common vole Microtus arvalis (Pallas, 1779) is becoming an increasingly popular model species to test evolutionary questions, including phylogeography (Martínková et al., 2013; Tougard et al., 2008; Triant & DeWoody, 2006). It is one of the most studied species within the Microtus genus, which is by far the most diverse genus recognized in rodents today (Mahmoudi, Darvish, Aliabadian, Moghaddam, & Kryštufek, 2017; Wilson et al., 2017), indicative of recent radiation and ongoing speciation process (Barbosa, Paupério, Pavlova, Alves, & Searle, 2018; Jaarola et al., 2004). The species meets the criteria to be a useful model system for testing biogeographical patterns (see Schmitt, 2007): It has the ability to spread rapidly into new habitats and their populations are sedentary and large enough to reflect phylogeographic signals. Microtus arvalis is also locally abundant and widely distributed across continental regions and Mediterranean peninsulas (Iberia, the Balkans, and the continental part of Italy) of the western Palaearctic (Figure 1), and ranging in altitude from sea level up to 3,000 m in the Alps (Yigit, Hutterer, Kryštufek, Amori, 2016). Consequently, many and diverse regions through the range, including southern peninsulas and continental areas, are suitable for the species, making M. arvalis a valuable representative of the continental fauna for evaluating alternative refugial scenarios.

Previous investigations of the phylogeography of the western arvalis form (M. arvalis arvalis) based on its mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variation have found several highly divergent lineages in Europe (Fink, Excoffier, & Heckel, 2004; Haynes, Jaarola, & Searle, 2003; Heckel, Burri, Fink, Desmet, & Excoffier, 2005; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016; Stojak, McDevitt, Herman, Searle, & Wójcik, 2015; Tougard et al., 2008). Overall, five main evolutionary mitochondrial lineages have been identified: Western, Central, Eastern, Italian, and Balkan (Figure 1). Some authors further distinguished between Western-North (France, Belgium and British Isles) and Western-South (Spain and Western France) lineages (Bužan, Förster, Searle, & Kryštufek, 2010; Fink et al., 2004; Haynes et al., 2003; Haynes et al., 2003; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak et al., 2015; Tougard et al., 2008). As the available M. arvalis population sequence data have increased and the analytical tools for phylogeographic inference have improved, different scenarios of isolation in refugia and postglacial colonization routes have been proposed. Some studies found support for the classical view, under which the species exclusively survived the ice ages in the southern peninsulas and expanded northward during the postglacial period (Haynes et al., 2003). While others provided evidence for the existence of extra-Mediterranean refugia located in Central and/or Eastern Europe (from Germany to the Carpathian Basin) (Fink et al., 2004; Heckel et al., 2005; Stojak et al., 2015; Tougard et al., 2008). Some of these studies, therefore, contrast with the classical view in considering southern refugia as areas driving high endemism, where mountain ranges may have precluded north–south postglacial dispersal and gene flow. Instead, recolonization would have originated from cryptic—continental—glacial refugia and rapidly expanded along a rough east–west axis (Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016; Stojak et al., 2015; Stojak, Wójcik, Ruczyńska, Searle, & McDevitt, 2016). However, whether one or more extra-Mediterranean refugia existed, their location, or whether they coincided with classical Mediterranean refugia are topics that remain largely unknown.

To gain a complete understanding of the phylogeographic history of this continental species model, and to contribute to our knowledge of European biogeographical patterns in general, it is necessary to explore the genetic structure of the species across its complete distribution range. In past studies, common vole populations at the extremes of the range, such as in the Iberian Peninsula, have been significantly underrepresented, limiting our capacity to make accurate inferences about its importance as a Mediterranean refugium and source of recolonization (Hewitt, 1999, 2001), as harbor of other refugia (i.e., “refugia-within-refugia” Abellán & Svenning, 2014; Gómez & Lunt, 2007), or potentially as driver of diversity and endemism. For instance, the Iberian Peninsula is of particular biogeographical interest since some authors consider that the Iberian vole (Microtus arvalis asturianus Miller, 1908) shows a number of unique characters that warrant subspecies recognition (Delibes & Brunett-Lecomte, 1980; González-Esteban, Villate, & Gosálbez, 1995; Nesterova, Mazurok, Rubtsova, Isaenko, & Zakian, 1998; Niethammer & Winking, 1971; Rey, 1973). Iberian voles have larger teeth and body size, longer pregnancy, larger litters, slower development of the young, distinctive threatening calls, and lower degree of intraspecific aggressiveness than the European common vole (M. a. arvalis) (Frank, 1968). To date, however, there has been no attempt to evaluate the Iberian common vole populations for subspecific status using molecular data and genetic methods.

In this study, we carried out the widest geographically reconstruction of the demographic history and dispersal dynamics of the common vole in Europe, using a continuous Bayesian phylogeographic diffusion approach (Lemey, Rambaut, Welch, & Suchard, 2010), across the entire European distribution of the species. We aimed to assess the generality of existing models about the origin, putative refugia, and dispersal of this continental model species in Europe by inferring the historical demography dynamic and spread of the species using spatially explicit analyses. Specifically, we asked (a) where is the most probable geographic location of the root of the European lineages of M. arvalis; (b) whether the spatial distribution of genetic variation observed in this species reflects colonization from a single glacial refugium or from multiple refugia; (c) whether the pattern of genetic variation is consistent with the existence of one or more Mediterranean refugia, one or more continental refugia, or a combination of Mediterranean and extra-Mediterranean refugia; and (d) whether the current geographic pattern observed in this continental mammal species is congruent with one of the common four paradigm patterns (Habel, Schmitt, & Müller, 2005; Hewitt, 1999, 2000) of postglacial range expansion from Mediterranean refugia (or, alternatively, whether refugial populations have remained within Mediterranean refugia as geographic isolates).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Population sampling and laboratory procedures

We sampled 261 common vole specimens from 10 localities throughout its range in the Iberian Peninsula (see details in Appendix 1 and Figure 1), using Sherman traps between 2012 and 2014. From each individual, we took 2-mm tissue biopsies from the ear and preserved them in 96% ethanol. Afterward, all individuals were released at their respective collection site, and tissue and DNA samples were stored at the Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos DNA data bank. All handling procedures were approved by the UCLM Ethics Committee (reference number CEEA: PR20170201) and in accordance with the Spanish and European policy for animal protection and experimentation. We completed our sampling with a compilation of 151 published cytochrome b sequences, collected in 68 localities across 22 countries covering the entire European range of M. arvalis (references and GenBank accession numbers are indicated in Appendix 1).

The phylogeographic architecture of common vole has traditionally been studied mainly using the mtDNA cytochrome b gene (Fink et al., 2004; Haynes et al., 2003; Heckel et al., 2005; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak et al., 2015; Stojak, Wójcik, et al., 2016; Tougard et al., 2008) or in combination with microsatellite and Y chromosome data (Beysard & Heckel, 2014; Stojak, Borowik, Górny, McDevitt, & Wójcik, 2019; Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016). Although some discordances are expected among gene tree topologies at different markers and the species tree (Kubatko, Carstens, & Knowles, 2009), previous studies on the phylogeography of this and related species suggest that mtDNA is an excellent marker for identification of glacial refugia and study of range expansion (Herman et al., 2014; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016). We are fully aware of the benefits of multilocus versus approaches single-marker approaches, but multilocus analyses would have constrained us to use a reduced number of populations. Moreover, former studies that have used autosomal and sex-chromosome markers in M. arvalis have provided congruent phylogeographical topologies and very similar patterns of genetic structure and dating events to those found with mtDNA (Beysard & Heckel, 2014; Braaker & Heckel, 2009; Heckel et al., 2005; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016), albeit much finer phylogenetic resolution was obtained with cytochrome b than with nuclear markers at the continental and regional scale (Heckel et al., 2005). Consequently, we used here this mitochondrial gene, given the need for sufficient resolution and direct comparison of our findings with earlier range-wide research on this species.

We digested samples overnight in 250 μl lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 0.005 M EDTA, 2% SDS, 0.2 M NaCl, pH 8.5) and Proteinase K (10 ng/μl) and extracted total genomic DNA from live specimens using a standard AcNH4 protocol. We adjusted DNA extractions to a working dilution of 25 ng/μl and PCR-amplified the entire cytochrome b mitochondrial gene (1,143 bp) using primers L7 (5′–ACCAATGACATGAAAAATCATCGTT–3′) and H6 (5′–TCTCCATTTCTGGTTTACAAGAC–3′) (Tougard et al., 2008). We cleaned up the PCR products using Exonuclease I and Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (Fermentas), and direct sequencing was performed with the same PCR primers and the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). We manually checked chromatograms for stop codons and obvious sequencing errors, and aligned them using the software BioEdit 7.0.5.3 (Hall, 1999). All the sequences obtained are deposited in GenBank (MG874847–MG874883).

2.2 Bayesian phylogeographic inference

We reconstructed the phylogeographic history of M. arvalis through continuous space and time, by modeling the spatial dispersion of its lineages using Bayesian phylogeographic inference in BEAST2 (Bouckaert et al., 2014; Lemey, Rambaut, Drummond, & Suchard, 2009; Lemey et al., 2010). This model combines geographic and genetic data, using the geographic location of each specimen and accommodating branch-specific variation in dispersal rates. For this analysis, we selected one sample per each haplotype found at each locality, totaling 197 sequences and 141 haplotypes, from 78 localities across 23 countries (Appendix 1). Our final alignment was restricted to a common length of 953 bp (Dataset S1). We created a xml input file in BEAUTI v.2 (Bouckaert et al., 2014), and used a jitter option of 0.50 to create unique coordinates for individuals collected at identical sites.

We used a marginal likelihood estimate (MLE) model selection procedure to evaluate the relative fit of our data to (a) models that assume no branch-specific rate variation in dispersal rates (i.e., homogeneous Brownian diffusion); and (b) relaxed random walk (RRW) models that assume different distributions for rate variation among branches (i.e., Cauchy RRW, lognormal RRW, and gamma RRW). We generated posterior distributions of each model by running 7 × 107 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) generations that were sampled every 7,000 generations, after discarding the first 10% samples as burn-in. We assessed convergence by visualizing the outputs of posterior distributions and effective sampling sizes (ESS) in TRACER v.1.4.8. (Rambaut & Drummond, 2007).

We then calculated Bayes factors for each model, and used them to select the spatial diffusion model that is best supported by the data. Bayes factors were derived from their MLE and based on path sampling (PS) method (Baele et al., 2012), MCMC chain of 1 × 106 generations and 50 path steps. Our data fitted best the Cauchy-distributed RRW diffusion rate model (MLE = −5,749.378); therefore, we applied this model to all subsequent analyses (gamma-distributed RRW: MLE = −6,468.140; lognormal-distributed RRW: MLE = −5,897.870, and homogeneous Brownian diffusion: MLE = −5,962.448).

To visualize the spatial diffusion of M. arvalis lineages, we inferred a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree and projected it on a spatial map. We ran four independent MCMC chains for 2.5 × 107 generations—using the BEAGLE library (Ayres et al., 2012) to improve computational performance—and sampled their posterior distributions every 2,500 generations. Following burn-in of the first 10% trees, we combined the four independent analyses using LogCombiner 2.4.1 (whereby all parameters reached ESS >200) and randomly subsampled 10,000 trees that were used to construct a MCC tree in TreeAnnotator 2.4.1. We used the resulting MCC tree as input for the program Spread 1.0.4 (Bielejec, Rambaut, Suchard, & Lemey, 2011) to generate a keyhole markup language file for visualizing spatial diffusion in Google Earth over the complete posterior distribution of trees. We used the Time Slicer function in Spread 1.0.4 to estimate the 80% highest posterior density (HPD) region of the unobserved ancestral locations for each branch that intersects ten specific time points, which roughly coincide with major internal nodes within the MCC tree: 50,700 years before present, ybp; 43,500 ybp; 36,300 ybp; 33,400 ybp; 23,700 ybp; 21,100 ybp (coincident with the last glacial maximum, LGM); 16,300 ybp; 12,600 ybp; 7,500 ybp, and the present.

We also explored temporal changes in the effective population size using a Bayesian skyride tree prior implemented in BEAST v. 1.8.1 (Drummond, Suchard, Xie, & Rambaut, 2012). We used the HKY model of sequence evolution and a strict molecular clock with an average substitution rate across the tree of µ = 3.27 × 10–7 substitutions/site/year (assuming a generation time of 1 year) (Martínková et al., 2013). We obtained this value from the most recently published—and likely most accurate—rate for cytochrome b of M. arvalis (Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016; Stojak et al., 2015; Stojak, Wójcik, et al., 2016), estimated using ancient DNA sequences from radiocarbon-dated specimens. We ran four independent MCMC chains for 3 × 107 generations sampling every 3,000 generations. Convergence was assessed in TRACER v.1.4.8. by confirming that the ESS for all parameters was higher than 200 and that independent runs yielded similar posterior distributions. We combined the four runs using LogCombiner v1.8.1 (http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/logcombiner) after discarding the first 10% of sampled generations as burn-in, and obtained estimates and credible intervals for each parameter and demographic reconstruction using TRACER v.1.4.8.

With the aim to infer within- and between-lineage evolutionary relationships among haplotypes analyzed, we constructed a median-joining network (Bandelt, Forster, & Röhl, 1999) using the software NETWORK 5.0 (available at http://www.fluxus-engineering.com/sharenet.htm). Genetic distances were calculated through a pairwise distance matrix in MEGA v. 7.0.16 (Kumar, Stecher, & Tamura, 2016).

3 RESULTS

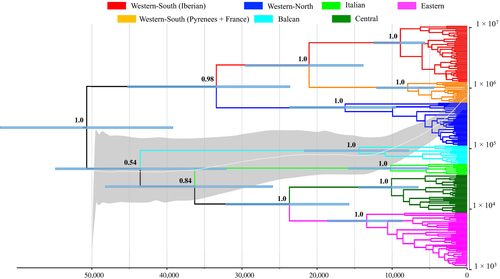

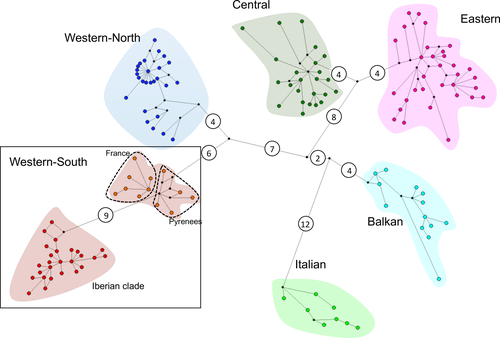

The MCC tree obtained using a Bayesian phylogeographic analysis with the Cauchy RRW model recovered with high support (all posterior probabilities = 1.0) all previously described mtDNA lineages of M. arvalis (Figure 2), and the network analysis provides congruent results (Figure 3). The Western group (including Western-North and Western-South lineages) was sister to the group that includes the Balkan, Italian, Central, and Eastern lineages. However, the low support received for the node of the Balkan lineage bifurcation at the root of this group means that the existence of a polytomy at the root of M. arvalis diversification cannot be ruled out. Within the Western-South lineage, we found further phylogenetic structure, where all the Iberian specimens formed a monophyletic group that was sister to M. arvalis from the rest of the lineage (including populations from Pyrenees and SW France; Figures 2 and 3). Sequence divergence between the Iberian and the rest of the Western-South clade (including French and Pyrenean populations) is comparable to the divergence levels found among other European lineages (Table 1).

| W-S (Iberian) | W-S (FR + Py) | Western-North | Balkan | Italian | Central | Eastern | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W-S (Iberian) | 0.0035 | ||||||

| W-S (FR + Py) | 0.0159 | 0.0037 | |||||

| Western-North | 0.0219 | 0.0210 | 0.0043 | ||||

| Balkan | 0.0269 | 0.0259 | 0.0264 | 0.0061 | |||

| Italian | 0.0344 | 0.0322 | 0.0313 | 0.0241 | 0.0057 | ||

| Central | 0.0310 | 0.0276 | 0.0268 | 0.0267 | 0.0247 | 0.0048 | |

| Eastern | 0.0293 | 0.0300 | 0.0294 | 0.0264 | 0.0248 | 0.0149 | 0.0080 |

Note

- The Iberian clade was separated from the rest of the Western-South (W-S) clade (France and Pyrenees).

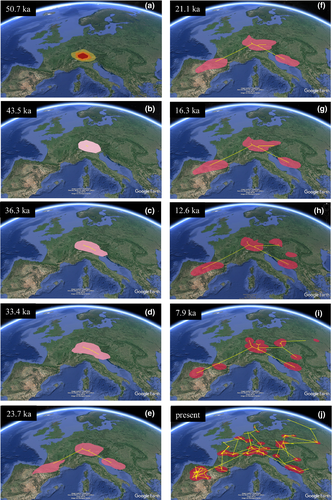

Based on the MCC tree, we inferred the most probable geographic location of the common ancestor of M. arvalis lineages in the alpine region of Switzerland–Liechtenstein, around 51,000 ybp (Figure 4a). From this region of origin, the Central European ancestor split into the two major ancestral lineages between 51,000 and 43,000 ybp. One ancestral lineage expanded to the southeast, resulting in the origin of the Balkan, Italian, Central, and Eastern lineages, and the other one expanded to the northwest, resulting in the ancestor of the current Western lineages (Figure 4a,b). Diversification in extant lineages and expansion of the eastern ancestral lineage occurred between 43,000 and 21,000 ybp along the Dalmatian (Adriatic) coast, from the western Austria Alps to the northwestern part of the Balkan Peninsula (Figure 4c–f). Over the same time period, the western ancestral lineage progressed toward the southwest of the continent, through central France to the Pyrenees. Colonization of the Iberian Peninsula was estimated to have occurred ~23,000–21,000 ybp (Figure 4e,f), following divergence of the Western-North and Western-South clades around 33,400 ybp (Figure 2). Finally, the Iberian clade split and further extended its geographic range during the last 9,000 years (Figures 2 and 4i,j), coinciding with the main period of diversification in all other extant lineages.

Our phylogeographic reconstruction also suggested that dispersal from Central Europe (Alps) to the east was geographically restricted (Figure 4a–h) until 12,600–7,900 years ago, when expansion proceeded within the range of the extant Central lineage along two axes: to the northeast, reaching the easternmost limit of the current distribution of M. arvalis in Russia–Mongolia, and to the southeast, reaching the southern part of the Carpathians region (Figure 4i). From then until present time, major northward range expansions occurred in populations of the Western, Central, and Eastern regions (Figure 4i,j). These recent expansion events resulted in the current distribution of the species across the Atlantic, boreal, and continental regions of Europe.

The skyride plot showed a long period of demographic stasis from the time of the most recent common ancestor of M. arvalis lineages (~50,000 ybp) until 35,000 ybp (Figure 2). Then, effective population size slowly increased until 18,500 ybp, likely associated with the major cladogenetic events in the history of M. arvalis. Finally, we detected a sudden increase in effective population size during the last 12,000 years, coinciding with the diversification and expansion of the current lineages of M. arvalis after the Younger Dryas (12.9–11.7 kya) cold reversal (Figure 2).

4 DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to understand how a continental small mammal species have responded to global climate changes in the past, especially through the late Pleistocene to Holocene transition. Accordingly, we used an extensive range-wide sampling of mtDNA variation and a Bayesian phylogeographic inference framework to reconstruct the evolutionary history of M. arvalis in continuous space and time.

In general, previous phylogeographic studies on M. arvalis consistently distinguish six mitochondrial lineages, and evidence for multiple glacial refugia during the last glaciation together with existence of refugia further north than traditional Mediterranean ones is now substantial (Bužan et al., 2010; Fink et al., 2004; Haynes et al., 2003; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak et al., 2019, 2015; Tougard et al., 2008). However, attempts to reconstruct the evolutionary history of each lineage (i.e., locate and circumscribe their origin, historical refugia, and postglacial colonization routes) have proved contentious (see below), with some discrepancy between inferences from studies made at different spatial resolutions and analytical methods.

Our data suggest that the species originated in Central Europe, and that the most likely locations of major glacial refugia were the peri-Alpine, peri-Pyrenean, and peri-Dinaric regions, confirming the existence of multiple glacial refugia for this continental species. Additionally, we found support for glacial survival in at least two classical Mediterranean refugia—in the Iberian and Balkan peninsulas—confirming a scenario of Pleistocene survival in multiple southern and northern refugia. But most interestingly, peninsular lineages are not found outside these areas and, consequently, southern peninsulas did not serve as sources of northward postglacial expansions, becoming centers of endemism for M. arvalis. Our results confirm the monophyly of Iberian common voles and the pre-LGM divergence between the Iberian and European phylogroups, which supports the status of the Iberian voles (M. a. asturianus) as a distinct subspecies in line with previous research (Delibes & Brunett-Lecomte, 1980; González-Esteban, Villate, & Gosálbez, 1994; González-Esteban et al., 1995; Nesterova et al., 1998; Niethammer & Winking, 1971; Rey, 1973). However, this observation should be treated with caution while it is confirmed by a synthetic approach that combines an additional sampling of different genes and morphological and ecological data. Our results, therefore, are generally consistent with recent research on M. arvalis based on DNA sequences and nuclear loci, but provide additional insights, particularly in the spatial location of the cradle, glacial refugia, and colonization routes.

Altogether, we propose that the classical model of southern glacial refugia in Mediterranean peninsulas, and posterior colonization of northern deglaciated areas (Hewitt, 2000), does not fit the evolutionary and demographic history of this continental species, as recent findings seem to corroborate (Schmitt & Varga, 2012; Tougard et al., 2008). Nor does this mammal species fit very well to the scenarios described so far for any of the biogeographical types of temperate continental species (Schmitt, 2007), which compared to our model tend to have greater geographic restrictions to the west in the location of refugia and lineage distributions. The species provide a paradigm of ice-age survival of temperate—continental—species in western and eastern Mediterranean peninsulas (sources of endemism) and multiple continental regions (sources of postglacial spread).

4.1 European glacial refugia and postglacial expansion

Our phylogenetic reconstruction was congruent with previous studies and recovered with high support six lineages of M. arvalis (Bužan et al., 2010; Fink et al., 2004; Haynes et al., 2003; Martínková et al., 2013; Stojak et al., 2015; Tougard et al., 2008). The well-delimited geographic distribution of these lineages exposes the importance of allopatric factors in shaping the genetic structure of this species at a continental scale, probably through multiple isolation events during the mid- and late Würm ice age (60,000–11,500 ybp). Our model-based phylogeographic analysis inferred the location of the most recent common ancestor of all haplotypes in a region between the Alps and southern Germany around 51,000 ybp (95% HPD: 62,400 –39,500 ybp). This location is consistent with the oldest fossil remains of M. arvalis found in SW Germany (Kowalski, 2001) and relates closely to what (Tougard et al., 2013) proposed as the common cradle of M. arvalis in “western Central Europe.” Moreover, our date estimates for the root of the tree and of major lineages coincided with recent research (Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016). This scenario is clearly not consistent with the fossil evidence (oldest fossil remains of M. arvalis in Central Europe from the Late Cromerian, 465,000 ybp; (Kowalski, 2001)) although accurate species identification in fossil remains appear to be problematic and should always be considered cautiously for this and related species (Navarro et al., 2018; Tougard, 2016). The extreme similarity between sibling vole species (Markova et al., 2010) and the morphological changes probably suffered by the species between the mid-Holocene and the present day are known to be unfavorable for diagnosing M. arvalis in the fossil record (Markova, Beeren, van Kolfschoten, Strukova, & Vrieling, 2012). Here, we focus on extant lineages, and therefore, we lack direct information about extinct lineages, which are often those found in the fossil record but that probably did not survive past periods (Tougard, 2016). This probably explains the large discrepancy in estimated origin and divergence times of major M. arvalis lineages between our study and the fossil evidence. In the future, research involving ancient DNA can contribute to shed light on these complex scenarios.

Even though the Bayesian posterior mean estimate should provide a reasonable basis for inferences, it is unwise to use our data to make strong statements about a single origin and subsequent lineage diversification or that different lineages originated more or less at the same time, given that 95% HPD estimate for the root of the tree overlaps with the origin of the Western, Italian, Balkan, and Central + Eastern lineages. In any case, M. arvalis could have survived in the Alps during the LGM and Younger Dryas periods (YD; 12,900–11,700 ybp, (Rasmussen et al., 2006), maybe in regions of lower elevation between the northern slope of the Alps and the Danube River in southern Germany. Most importantly, this area could represent not only the origin of dispersal for the species in Europe, but also an extra-Mediterranean glacial refugium.

The timing and pattern of cladogenetic events also point to geographic isolation during the last glaciation as the major driver of lineage divergence, as well as to the existence of multiple refugia for M. arvalis. Most of the major splits between lineages occur around the time of the LGM, such as the split between Western-North and Western-South lineages (mean: 34,028 ybp. 95% HPD: 45,447–23,882 ybp), the split between Eastern and Central lineages (mean: 24,072 ybp. 95% HPD: 15,823–32,275 ybp), or the split between the Iberian and Western-South lineages (mean: 21,069 ybp. 95% HPD: 29,743–14,087 ybp). For instance, the most recent common ancestor of the Eastern lineage was located west of the Danube River around 13,639 ybp (95% HPD: 18,809–8,820 ybp), which could imply that a glacial refugium in the eastern Alps was the origin of this lineage. However, based on the molecular data alone, we cannot rule out the existence of a Carpathian refugium, as it has been proposed for numerous species (Kotlik et al., 2006; Pazonyi, 2004; Sommer & Nadachowski, 2006) including M. arvalis (Stojak et al., 2019, 2015).

Similarly, the high differentiation of the Balkan lineage relative to the other Central Eastern lineages could be the result of allopatric divergence, following isolation in a Ponto-Mediterranean refugium in the northwestern Dalmatian coast (Dinaric Alps). Furthermore, and despite the co-occurrence of both Eastern and Balkan haplotypes in that region at the present time (Bužan et al., 2010; Stojak et al., 2015), it appears that the Balkan lineage has historically maintained a very restricted distribution, and has not expanded nor contributed to the gene pool of northern or eastern European populations. The large and recent expansion detected (Figure 4) in populations of the Eastern lineage to the center and northwestern Balkan Peninsula and south of the Danube River would explain their presence there. Based on these, we could first consider the Balkan Peninsula as a region of endemism of M. arvalis, and second, refute previous hypotheses suggesting that the Eastern lineage originated from a refugium in the Balkans (Haynes et al., 2003; Heckel et al., 2005).

Within the Western-South lineage, the split between the Iberian and the French clades around the LGM suggests divergence in two separate refugia. One refugium might have existed near the region of Aquitaine, in southwestern France (i.e., Pyrénées-Atlantiques), from where the species likely expanded to northern Europe, and another one south of Pyrenees—or south of the Ebro River Valley—that further extended to the center and northwest of the Iberian peninsula. According to the temporal-spatial diffusion pattern, the Iberian Peninsula served as a glacial (Mediterranean) refugium for extant populations of common vole during the last cold stage of the Pleistocene, including the LGM. This Iberian clade, however, did not back-colonize the Pyrenees or France during the present interglacial period, as could be deduced by the absence of Iberian haplotypes in populations of these two regions. The Holocene expansion of Iberian voles could have been limited ecologically—maybe by predators or competition with closely related species—or geographically, by physical barriers such as the Ebro River following deglaciation (see below). Consequently, Iberian voles can be considered as a long-term isolated endemism of the Iberian Peninsula (see also Tougard et al., 2008) without admixture with other mitochondrial lineages, and concordant with previous subspecific designation. The most recent common ancestor of tentative M. a. asturianus specimens was estimated around 9,000 ybp in north-central Spain, and the more recent split within this clade was dated 8,500–4,000 years ago. The geographic expansion of the Iberian clade during the late Holocene (i.e., last 5,000 years) seems to be a key factor shaping its current population genetic structure.

In Central Europe, the presence of a glacial refugium has already been suggested for M. arvalis (Fink et al., 2004; Tougard et al., 2008), and for other species (reviewed in Schmitt & Varga, 2012), but for the first time we were able to pinpoint its geographic location using model-based phylogeographic inference. There is good evidence that several continental species had multiple differentiation centers around the European high mountain systems (Schmitt, 2007; Stewart & Lister, 2001), possibly due to the existence of more humid conditions around these mountains in a context of increased dryness westward during the coldest phases of the Pleistocene in Europe. For this group of species, it has been argued that water-limited conditions, rather than temperature, may have limited the species’ glacial distributions along an east–west gradient in response to moisture (Schmitt, 2007), and there is recent evidence of the importance of climate for the genetic structure of this and related species (Stojak et al., 2019).

Our analyses, however, failed to conclude whether only one or multiple refugia occurred scattered along the Alps and adjacent areas. Multiple glacial refugia have been proposed along the northern, southern, southwestern, and eastern slopes of the Alps (Schönswetter, Stehlik, Holderegger, & Tribsch, 2005). Particularly for M. arvalis, the Alpine region is a well-known contact zone between three evolutionary lineages (Western-North, Central, and Italian), and both the northern and southern slopes of the Alps have been proposed as sources of post-LGM recolonization (Braaker & Heckel, 2009). Interestingly, the inferred location and time for the origin of expansion of the current lineages of M. arvalis coincide with the main routes of westward expansion of agriculture in Europe during the Neolithic period ~10,200–2,000 ybp (Larson et al., 2007; Rowley-Conwy, 2011). The treeless tundra or steppe that had previously extended over much of Europe was progressively replaced by woodlands from the beginning of the Holocene, 11,000 years ago (Hejcman, Hejcmanová, Pavlŭ, & Beneš, 2013; Huntley & Birks, 1983; Turner & Hannon, 1988). Thus, it could be argued that the clearance of woodlands to turn them into cultivated lands (Roberts et al., 2018), and the progressive anthropogenic transformations of the landscape (Bouma, Varralyay, & Batjes, 1998; Garcia, Alda, et al., 2011; Garcia, Mañosa, et al., 2011; Novenko, Volkova, Nosova, & Zuganova, 2009; O’Connor & Shrubb, 1986; Ruddiman, 2003), could have facilitated the expansion and connectivity of populations of steppe and grassland species in a postglacial environment (Bouma et al., 1998; Garcia, Alda, et al., 2011; Garcia, Mañosa, et al., 2011; O’Connor & Shrubb, 1986; Pärtel, Bruun, & Sammul, 2005).

The geographic structure of the lineages of M. arvalis also hints at factors limiting postglacial recolonization and/or current dispersal of the species. The major mtDNA lineages of M. arvalis in Central Europe are well delimited by the major river systems (Figure 1). For example, the Loire and Rhone rivers in France divide the Western-North and Western-South lineages, something already indicated by Tougard et al. (2008). Likewise, the Ebro River in Spain separates the tentative M. a. asturianus specimens and M. a. arvalis from the Western-South clade, which includes populations from the Pyrenees and southern France. Overall, the distribution of M. a. asturianus in Iberia is limited to the north and south by the Ebro and Tajo rivers, respectively. The range of the Italian lineage is also limited to the south by the Po, and the Central lineage is roughly delimited by the transitional zone between Oder and Vistula to the west and by the Danube to the south (Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016; Stojak, Wójcik, et al., 2016). Furthermore, the part of the Danube basin in the eastern Balkan region seems to represent a geographic boundary between the Balkan and Eastern lineages. Similarly, and in view of the current geographic distribution (Figure 1), the Don-Volga river system marks the eastern limit of the arvalis range (Bulatova et al., 2007; Jaarola et al., 2004; Tougard et al., 2013). As could be expected, these barriers are porous, and most lineages show haplotypes that have leaked to the other side of these rivers, somewhat blurring the boundaries between lineages near the headwaters. This could either be a consequence of recent dispersal during periods of reduced runoff in the Holocene (Bernárdez et al., 2008; Combourieu-Nebout et al., 2013), or by passage through river headwaters, where lineages often come into contact (Fouquet et al., 2012). In fact, most European lineages of M. arvalis meet in a Central European region near de Alps (Figure 1), which coincides also with the headwaters of the major European rivers. Even more recently, river bridges and other human infrastructures also allow voles to cross these barriers. More populations from putative areas of secondary contact and lineage admixture, as well as the use of additional nuclear genetic markers, will be used in future studies to assess patterns of hybridization and introgression between lineages.

Our findings, therefore, provide support for a major role of large European river systems in shaping geographic boundaries of M. arvalis (Stojak, McDevitt, et al., 2016). In contrast to the widely accepted role of mountain systems (e.g., Alps and Pyrenees) precluding postglacial expansion of many temperate species in southern Mediterranean peninsulas (Habel et al., 2005; Hewitt, 1999; Schmitt, 2007), or the role of humans as responsible for the colonization of some islands (Martínková et al., 2013), very little is known about a similar potential role of rivers.

It is expected that during the deglaciation of Europe, the distribution and extent of freshwater systems suffered dramatic changes; these had a significant effect in the postglacial recolonization of terrestrial species. When ice sheets started to retreat from their maximum extent, between 22,000 and 17,000 ybp, there was an increased meltwater production and river water runoff, causing a sudden reactivation of the hydrological cycle (Mangerud et al., 2004; Ménot et al., 2006). Therefore, these water bodies may have played a dual role, either as barriers for dispersal, and/or as corridors, along water banks, consequently affecting gene flow and genetic differentiation, especially in small mammals or species with low vagility such as voles.

In conclusion, M. arvalis represents a remarkable study organism that combines attributes of continental and Mediterranean faunal elements (De Lattin, 1967; Schmitt & Varga, 2012). On one hand, Central Europe acted as a glacial refugium and as a source for other European populations, and on the other hand, additional Mediterranean refugia acted as drivers of endemism. Although there is abundant literature on Mediterranean species that found shelter in extra-Mediterranean glacial retreats (Provan & Bennett, 2008; Schmitt & Varga, 2012), very few studies report continental species in both Mediterranean and extra-Mediterranean refugia. The pattern we describe for the common vole is, however, highly congruent with the phylogeographical pattern in the bank vole M. glareolus, a European forest vole species with Mediterranean and continental refugia, and in which the Mediterranean phylogroups did not contribute to the postglacial recolonization of much of their range (Deffontaine et al., 2005). To the best of our knowledge, so far, the co-occurrence among Mediterranean and extra-Mediterranean glacial refugia for continental species is mainly restricted to eastern Europe, with few examples referred to continental species with refugial areas in the Balkan Peninsula, such as butterflies (Gratton, Konopiński, & Sbordoni, 2008; Junker et al., 2015; Schmitt, Rákosy, Abadjiev, & Müller, 2007), reptiles (Ursenbacher, Carlsson, Helfer, Tegelström, & Fumagalli, 2006), and invertebrates (Pinceel, Jordaens, Pfenninger, & Backeljau, 2005). Whether M. arvalis majorly follows a continental or a Mediterranean specific biogeographical pattern (Schmitt, 2007) is still unclear, in part because of the difficulty to classify ecologically diverse and widely distributed species. More research on continental species is needed to test the generality of the biogeographical pattern of M. arvalis in Europe.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank students and friends for their help in the field and especially to Iván García Egea and Jorge Piñeiro Álvarez for invaluable assistance collecting samples. Also, we would like to also thank the numerous landowners who allowed us access to their properties, and acknowledge the support and cooperation of GREFA, and the communities from the villages of Villalar de los Comuneros, Boada de Campos, San Martín de Valderaduey, and Fuentes de Nava. We also thank Elisabeth Haring (Editor-in-Chief of JZSER) and two reviewers for constructive and helpful comments of this manuscript. This work was supported by I + D National Plan Projects of the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (CGL2011-30274, CGL2015-71255-P, CGL2013-42451-P), and the Fundación BBVA Research Project TOPIGEPLA (2014 call).

APPENDIX 1: List of all M. arvalis haplotypes used for Bayesian analysis of the cytochrome b gene in this study, geographic location and number of different haplotypes in each locality (NH). The numbers in parentheses correspond with localities in Figure 1.

| Geographic origin | Ref. | NH | Lat. | Long. | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kranj; Slovenia (1) | a | 1 | 46.24 | 14.36 | GU187381 |

| Ljubljana; Slovenia (2) | a | 2 | 46.04 | 14.52 | GU187382-3 |

| Gacko; Bosnia (3) | a | 4 | 43.10 | 18.33 | GU187368, GU187373, GU187376-7 |

| Kupres, BH; Bosnia (4) | a | 4 | 43.56 | 17.11 | GU187365-7, GU187369 |

| Mt. Zelengora; Bosnia (5) | a | 4 | 43.15 | 18.35 | GU187368, GU187373-5 |

| Bosanski Petrovac; Bosnia (6) | a | 1 | 44.35 | 16.21 | GU187384 |

| Mt.Šator; Bosnia (7) | a | 1 | 44.09 | 16.37 | GU187385 |

| Mt. Komovi; Montenegro (8) | a | 2 | 42.42 | 19.39 | GU187378-9 |

| Slano Kopovo; Serbia (9) | a | 2 | 45.20 | 20.10 | GU187384, GU187362 |

| Mt. Suva planina; Serbia (10) | a | 1 | 43.07 | 22.16 | GU187380 |

| Białowieża; Poland (11) | b | 3 | 52.42 | 23.52 | KP255605-7 |

| Popówka; Poland (12) | b | 3 | 52.04 | 23.26 | KP255614-6 |

| Sochaczew; Poland (13) | b | 3 | 52.13 | 20.14 | KP255599-601 |

| Poddębice; Poland (14) | b | 3 | 51.54 | 18.58 | KP255587-9 |

| Łowicz; Poland (15) | b | 3 | 52.06 | 19.56 | KP255602-4 |

| Chernobyl; Ukraine (16) | c | 1 | 51.27 | 30.22 | U54488 |

| Buchak; Ukraine (17) | b | 3 | 49.87 | 31.43 | KP255618-20 |

| Vienna; Austria (18) | d | 2 | 48.38 | 16.35 | AY708460-1 |

| Brussels; Belgium (19) | d | 4 | 50.80 | 4.35 | AY708508-10, AY708462 |

| Stalhille; Belgium (20) | e | 2 | 51.21 | 3.07 | GU190540, GU190536 |

| Vetrkovice; Czech Republic (21) | d | 4 | 49.76 | 17.80 | AY708471-3, AY708505 |

| Drnholec; Czech Republic (22) | f | 2 | 48.85 | 16.48 | FR865434 |

| Nosislav; Czech Republic (23) | f | 2 | 49.00 | 16.65 | FR865432-3 |

| Studenec; Czech Republic (24) | f | 1 | 50.55 | 15.53 | FR865434 |

| Freiburg; Germany (25) | g | 7 | 48.00 | 7.80 | FJ789987, FJ789989, FJ790014-8 |

| Heilsbronn; Germany (26) | d | 3 | 49.32 | 10.80 | AY708476-8 |

| Alflen; Germany (27) | e | 2 | 50.18 | 7.04 | GU190616-7 |

| NE Hamburg; Germany (28) | e | 2 | 53.60 | 10.05 | GU190662-3 |

| Schiltach; Germany (29) | e | 1 | 48.30 | 8.34 | GU190618 |

| Rosenheim; Germany (30) | g | 2 | 47.85 | 12.12 | FJ790019-20 |

| Aigle; Switzerland (31) | g | 4 | 46.35 | 6.92 | FJ789990-1, AY708519, FJ790029 |

| Lausanne; Switzerland (32) | g | 4 | 46.57 | 6.55 | AY708514, AY708467-9 |

| Walenstadt; Switzerland (33) | g | 3 | 47.12 | 9.30 | AY708519, FJ790011-2 |

| Chur; Switzerland (34) | g | 2 | 46.83 | 9.48 | AY708512, AY708466 |

| Mont-la-ville; Switzerland (35) | g | 3 | 46.63 | 6.40 | AY708510, FJ790005, FJ790029 |

| Trento; Italy (36) | h | 1 | 46.06 | 11.11 | AY220766 |

| Laas; Italy (37) | g | 1 | 46.62 | 10.70 | FJ789995 |

| Bozen; Italy (38) | g | 1 | 46.50 | 11.30 | FJ790024 |

| Marling; Italy (39) | g | 2 | 46.65 | 11.13 | FJ790025, AY220766 |

| Neumarkt; Italy (40) | g | 1 | 46.32 | 11.27 | FJ790026 |

| Bendern; Liechtenstein (41) | g | 1 | 47.22 | 9.50 | FJ790031 |

| Ruggell; Liechtenstein (42) | g | 2 | 47.23 | 9.52 | FJ790030, FJ790032 |

| Nagycsány; Hungary (43) | h | 1 | 45.86 | 17.95 | AY220769 |

| Velké Kosihi; Slovakia (44) | h | 1 | 47.76 | 17.88 | AY220767 |

| Stebník; Slovakia (45) | h | 1 | 49.38 | 21.27 | AY220768 |

| Hjerl Hede; Denmark (46) | h | 1 | 56.48 | 8.87 | AY220776 |

| Nørre Farup; Denmark (47) | e | 2 | 55.35 | 8.73 | GU190660-1 |

| Lauwersee; Netherlands (48) | h | 1 | 53.38 | 6.18 | AY220778 |

| Pumerend; Netherlands (49) | e | 2 | 52.51 | 4.94 | GU190512, GU190516 |

| Oostburg; Netherlands (50) | e | 1 | 51.33 | 3.49 | GU190531 |

| Mantet; Pyrenees (51) | h | 1 | 42.48 | 2.30 | AY220789 |

| Vernet les Bains; Pyrenees (52) | e | 1 | 42.50 | 2.35 | GU190383 |

| Plà de Beret; Pyrenees (53) | e | 3 | 42.72 | 0.84 | GU190385, GU190388-9 |

| Luumäki; Finland (54) | h | 1 | 60.91 | 27.56 | AY220770 |

| Nuijamaa; Finland (55) | h | 1 | 60.95 | 28.57 | AY220770 |

| Vladimir; Russia (56) | h | 1 | 56.13 | 40.42 | AY220771 |

| Zvenigorod; Russia (57) | h | 1 | 55.73 | 36.85 | AY220770 |

| Luxemburg; Luxemburg (58) | e | 2 | 49.61 | 6.13 | GU190395-6 |

| Aiffres; France (59) | e | 4 | 46.29 | −0.41 | GU190547-50 |

| Armendarits; France (60) | e | 1 | 43.30 | −1.17 | GU190634 |

| Baie de l'Aiguillon; France (61) | e | 3 | 46.30 | −1.17 | GU190417-8, GU190421 |

| Cissé; France (62) | e | 4 | 46.64 | 0.23 | GU190552-5 |

| Ste. Marie du Mont; France (63) | e | 4 | 49.38 | −1.23 | GU190566-7, GU190569-70 |

| Pihen lès Guînes; France (64) | e | 2 | 50.87 | 1.79 | GU190604, GU190606 |

| Outre; France (65) | e | 4 | 46.08 | 3.03 | GU190411-3, GU190415 |

| Les Forts; France (66) | e | 3 | 48.33 | 1.18 | GU190557-8, GU190560 |

| Crépaillat; France (67) | e | 3 | 46.14 | 2.74 | GU190405-6, GU190408 |

| Arbejal; Spain (68) | i | 5 | 42.88 | −4.50 | MG874847, MG874849, MG474853-5, |

| Bello; Spain (69) | i | 5 | 40.92 | −1.50 | MG874851, MG874856-9 |

| Ventosa del Río Almar; Spain (70) | i | 5 | 40.94 | −5.31 | MG874854, MG874863, MG874870, MG874872, MG874877 |

| Campo Azálvaro; Spain (71) | i | 5 | 40.68 | −4.38 | MG874847, MG874849, MG874854, MG874865-6 |

| Chañe; Spain (72) | i | 3 | 41.33 | −4.39 | MG874849, MG874854, MG874870 |

| San Emiliano; Spain (73) | i | 4 | 42.96 | −6.02 | MG874860, MG874873-5 |

| Grañón; Spain (75) | i | 5 | 42.46 | −3.02 | MG874850, MG874854, MG874860, MG874867, MG874871 |

| Milles de la Polvorosa; Spain (76) | i | 2 | 41.92 | −5.73 | MG874860, MG874863 |

| Revilla de Campos; Spain (77) | i | 5 | 42.01 | −4.71 | MG8741847, MG874863, MG874873, MG874860-1 |

| San Martín de Valderaduey; Spain (78) | i | 7 | 41.81 | −5.47 | MG8741847, MG874860-1, MG874868, MG874863-4, MG874876 |

| Nofels; Austria (79) | g | 2 | 47.15 | 9.34 | FJ790031-2 |