Insights into the evolutionary history of Cervus (Cervidae, tribe Cervini) based on Bayesian analysis of mitochondrial marker sequences, with first indications for a new species

Contributing author: Luisa Garofalo ([email protected])

Abstract

Molecular phylogeny and evolutionary history of Cervus, the most successful and widespread cervid genus, have been extensively addressed in Europe, fairly in eastern Asia, but scarcely in central Asia, where some populations have never been phylogenetically investigated with DNA-based methods. Here, we applied a coalescent Bayesian approach to most Cervus taxa using complete mitochondrial cytochrome b gene and control region to provide a temporal framework for species differentiation and dispersal, with special emphasis on the central Asian populations from the Tarim Basin (C. elaphus bactrianus, C. elaphus yarkandensis) and Indian Kashmir (C. elaphus hanglu) aiming at assessing their phylogenetic and phylogeographic patterns. Red deer (C. elaphus), wapiti (C. canadensis) and sika deer (C. nippon) are confirmed as highly differentiated taxa, with genetic distances, divergence times and phylogenetic positions compatible with the rank of species. Similarly, the red deer of the Tarim group, hitherto considered as subspecies of C. elaphus, showed a comparable pattern of genetic distinction in the phylogeny and, according to our results, are thus worthy of being raised to the species level. The systematic position of the endangered red deer from Indian Kashmir is assessed here for the first time, and implications for its conservation are also outlined. Based on phylogeny and divergence time estimates, we propose a novel evolutionary pattern for the genus Cervus during the Mio/Pliocene, in the light of palaeo-climatological information.

Introduction

The genus Cervus covers most of the Holarctic region, from northern Africa and western Europe across Asia to North America, showing a broad range of morphological and behavioural adaptations to different environments (e.g. Grubb 2006). The ancestors of Cervus may have been sika-like deer (i.e. 6-tined medium-sized deer) that occurred at the Mio/Pliocene boundary in central and western Asia (Di Stefano and Petronio 2002), where most of the extant species of Cervini [with the exception, for example, of Dama dama (Linnaeus, 1758)] still live. In Asia, they differentiated and started to radiate, following climatic and orogenic changes in this continent during the Pliocene (Gilbert et al. 2006; Sun et al. 2008). A variable number of polytypic species have originally been recognized in Cervus based mainly on the morphology of living taxa (cf. Meijaard and Groves 2004; Groves and Grubb 2011). Of these, the red deer Cervus elaphus Linnaeus, 1758, and the sika deer Cervus nippon Temminck, 1838, are presently the most abundant, with red deer that is widespread throughout the distribution area, and sika deer occurring in north-eastern Asia, from Siberia to North Vietnam, Taiwan and Japan. Currently, the red deer from central-eastern Asia and North America (i.e. the wapiti group, previously ascribed to C. elaphus) have been ranked as a separate species, Cervus canadensis (Erxleben, 1777), by recent molecular phylogenies (Randi et al. 2001; Ludt et al. 2004; Pitra et al. 2004). By contrast, taxonomy at the subspecific level still remains unclear. Morphology and molecules failed to produce the same classification (cf. Meijaard and Groves 2004). Discrepancies may be due to the lack, in molecular studies, of an extensive sampling that is hardly feasible for large mammals with wide distributions. On the other hand, morphological characters in Cervids, such as antler shape, body size and colour, largely reflect adaptations to local environmental conditions (Lister 1989), and, if used as evolutionary traits for phylogenies, they can sometimes be misleading because of high levels of homoplasy. Consequently, they are not always reliable features in systematic assessments.

While the red deer in Europe and the wapiti in North America have been well studied, much less is known of Asiatic populations. In particular, the Kashmir red deer, or hangul (Cervus elaphus hanglu), confined at low numbers to the Dachigam National Park and neighbouring areas, in the western part of the Great Himalayan region (Jammu and Kashmir State, India), has never been phylogenetically studied using mitochondrial sequences, so far. Based on morphology and geographical distribution, C. e. hanglu has alternatively been considered as synonym of Cervus elaphus yarkandensis and Cervus elaphus wallichi (Whitehead 1972), or as belonging to a ‘wallichi-group’ semispecies, together with Cervus elaphus bactrianus, C. e. yarkandensis, C. e. wallichi, Cervus elaphus macneilli and Cervus elaphus kansuensis (Groves and Grubb 1987). Moreover, the assignment of the central Asian Tarim group (C. e. bactrianus and C. e. yarkandensis) to C. elaphus, as well as its ancestral status, is still debated (Mahmut et al. 2002; Polziehn and Strobeck 2002; Ludt et al. 2004; Pitra et al. 2004). Nor is it clear to which taxonomic rank they can be assigned.

Efficient conservation requires a sensible nomenclature, accepted by international conventions. Restricting protection measures to species, subjectively defined, may prove unwise, as interfecund, but genetically different populations may become extinct while scientists discuss about their names. The genus Cervus has a wide distribution, and many different populations deserve protection. Yet, the taxonomy of this genus is far from being clarified.

Aims of our work were as follows: (1) to provide a temporal framework for species differentiation and dispersal of Cervus using a coalescent Bayesian approach based on the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cytb) and control region (CR) markers; (2) to clarify whether C. e. yarkandensis and C. e. bactrianus red deer are ancestral and belong to C. elaphus; (3) to infer the phylogenetic position of the endangered Kashmir red deer, unknown to date; (4) to propose a novel evolutionary pattern for the genus Cervus based on our results, in the light of palaeo-climatological information.

Material and Methods

Samples and laboratory methods

A total of 81 cytb and CR sequences were used to reconstruct our Cervus phylogenetic trees using both specimens collected ex novo for this study and data from the literature (see Table 1 for details). Tissue samples (muscle, skin, blood) were obtained from red deer found dead or caught in the wild by zoologists during other research projects. Total genomic DNA was isolated using the DNA IQTM Casework Sample Kit and the Maxwell 16 LEV System (Promega, Madison, FL, USA). DNA preparations are in the collection of Forensic Genetic Laboratory of Centro di Referenza Nazionale per la Medicina Forense Veterinaria (Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Regioni Lazio e Toscana, Italy). The mitochondrial complete CR was amplified via PCR using the external primers H-Phe (Jäger et al. 1992) and CST2 (Polziehn and Strobeck 2002). PCRs were performed in a Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a final volume of 25 μl, containing 50–100 ng template DNA, 2.5 μl 10× Gold buffer (Applied Biosystems), 200 μm of each dNTP, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 1 μl of 2.5 μg μl−1 BSA (bovine serum albumin), 15 pm of each primer and 1 U of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Applied Biosystems). Amplification profile consisted of an initial 3-min denaturation step at 94°C, 38 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C as annealing temperature and 2-min extension step at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced with Big Dye Terminator v. 3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems) in both forward and reverse directions using the amplification primers and two additional internal primers: CST25 and CST29 (Polziehn and Strobeck 2002). Sequences were purified using Cleanseq Dye-Terminator magnetic bead system (Agencourt, Beckman Coulter, Beverly, MA, USA) and loaded onto a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

| Haplotype ID | (Sub)species | Geographical provenance | cytb Acc. No. ref. | CR Acc. No. ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAC1 | C. e. bactrianus Lydekker, 1900 | Tadzikistan | AY142327 1 | |

| BAC2 | C. e. bactrianus Lydekker, 1900 | Unknown | KF141939 2 | |

| YAR1 | C. e. yarkandensis Blanford, 1892 | Ürümki, Sinkiang, China | AY142326 1 | |

| YAR2 | C. e. yarkandensis Blanford, 1892 | Unknown | NC013840 3 | |

| YAR3 | C. e. yarkandensis Blanford, 1892 | Unknown | GU457435 3 | |

| HAN1 | C. e. hanglu Wagner, 1844 | Kashmir, India (2) | KP859324 15 | KP859318 15 |

| HAN2 | C. e. hanglu Wagner, 1844 | Kashmir, India (2) | KP859324 15 | KP859319 15 |

| MAR1 | C. e. maral Ogilby, 1840 | Iran | AF489280 1 | |

| MAR2 | C. e. maral Ogilby, 1840 | Turkey | AY118199 1 | |

| ATL1 | C. e. atlanticus Lönnbert, 1906 | Norway | AY070226 1 | |

| ATL2 | C. e. atlanticus Lönnbert, 1906 | Norway | AF291888 4 | |

| HIP1 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Hungary | AF489279 1 | |

| HIP2 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Bulgaria | AF423195 1 | |

| HIP3 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Austria | AY044857 1 | |

| HIP4 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | France | AY244491 1 | |

| HIP5 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Germany | AY044858 1 | |

| HIP6 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Poland | AY044860 1 | |

| HIP7 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Ukraine | AY148966 1 | |

| HIP8 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Yugoslavia | AY070225 1 | |

| HIP9 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Austria, eastern Italian Alps, central Apennines (3) | KP859321 15 | |

| HIP10 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Austria (2) | KP859322 15 | |

| HIP11 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Eastern Italian Alps (1) | KP859323 15 | |

| HIP12 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Unknown | NC007704 5 | |

| HIP13 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Unknown | AF016972 6 | |

| HIP14 | C. e. hippelaphus Erxleben, 1777 | Unknown | AF016973 6 | |

| HIS1 | C. e. hispanicus Hilzheimer, 1909 | La Garganta, Spain | AF489281 1 | |

| HIS2 | C. e. hispanicus Hilzheimer, 1909 | Spain | AF291889 4 | |

| BAR1 | C. e. barbarus Bennett, 1833 | Tunisia | AY070222 1 | |

| BAR2 | C. e. barbarus Bennett, 1833 | Unknown | AF296807 7 | |

| COR1 | C. e. corsicanus Erxleben, 1777 | Sardinia | AY244489 1 | |

| COR2 | C. e. corsicanus Erxleben, 1777 | Unknown | AF291885 4 | |

| ITAL | C. e. italicus Zachos, Mattioli, Ferretti, Lorenzini, 2014 | Mesola, Italy (10) | KP859325 15 | KP859320 15 |

| WALL | C. c. wallichi Cuvier, 1823 | Tibet, China | AY044861 1 | |

| MAC1 | C. c. macneilli Lydekker, 1909 | Qinghai, China | AY035875 1 | |

| MAC2 | C. c. macneilli Lydekker, 1909 | Unknown | AF296810 7 | |

| XAN1 | C. c. xanthopygus Milne-Edwards, 1867 | Amur, Russia | AF423197 1 | |

| XAN2 | C. c. xanthopygus Milne-Edwards, 1867 | Manchuria | AF296817 1 | |

| ALA1 | C. c. alashanicus Bobrinskii and Flerov, 1935 | North-eastern China | AY070224 1 | |

| ALA2 | C. c. alashanicus Bobrinskii and Flerov, 1935 | Unknown | AF296818 7 | |

| KAN1 | C. c. kansuensis Pocock, 1912 | Dong Da Shan, China | AY070223 1 | |

| KAN2 | C. c. kansuensis Pocock, 1912 | Kansu, China | AF296819 7 | |

| SON1 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | AY035871 1 | |

| SON2 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | AY044856 1 | |

| SON6 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | HQ191429 8 | |

| SON7 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | GQ304772 9 | |

| SON8 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | KF781104 10 | |

| SON9 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | KF781098 10 | |

| SON10 | C. c. songaricus Severtzov, 1873 | Tien Shan, China | FJ969444 8 | |

| SIB1 | C. c. sibiricus Severtzov, 1873 | Mongolia | AF423199 1 | |

| SIB2 | C. c. sibiricus Severtzov, 1873 | Mongolia | AY044862 1 | |

| SIB3 | C. c. sibiricus Severtzov, 1873 | Unknown | AF058369 6 | |

| SIB4 | C. c. sibiricus Severtzov, 1873 | Unknown | AF0583706 | |

| SIB5 | C. c. sibiricus Severtzov, 1873 | Unknown | AF058371 6 | |

| CAN1 | C. c. canadensis Erxleben, 1777 | North America | AF423198 1 | |

| CAN2 | C. c. canadensis Erxleben, 1777 | North America | AB021096 11 | |

| KORE | C. c. canadensis Erxleben, 1777 | South Korea | EF139147 12 | |

| ROOS | C. c. roosevelti Merriam, 1897 | Oregon, North America | AF016971 6 | |

| NELS | C. c. nelsoni V. Bailey, 1935 | Oregon, North America | AF016980 6 | |

| MAN1 | C. c. manitobensis Millais, 1915 | Unknown | AF016960 6 | |

| MAN2 | C. c. manitobensis Millais, 1915 | Unknown | AF005197 6 | |

| NANN | C. c. nannodes Merriam, 1905 | Unknown | AF016977 6 | |

| CENT | C. n. centralis Kishida, 1936 | Honshu, Japan | AB021094 11 | |

| YESO | C. n. yesoensis Heude, 1884 | Hokkaido, Japan | AB021095 11 | |

| KERA | C. n. keramae Kuroda, 1924 | Kerama Islands, Japan | AB021091 11 | |

| PULC | C. n. pulchellus Imaizumi, 1970 | Tsushima Island, Japan | AB021090 11 | |

| MAGE | C. n. mageshimae Kuroda and Okada, 1951 | Tanegashima and Mageshima Islands, Japan | AB021092 11 | |

| NIP1 | C. nippon Temminck, 1838 | Unknown | AF016975 6 | |

| NIP2 | C. nippon Temminck, 1838 | Unknown | U12868 13 | |

| HORT | C. n. hortulorum Swinhoe, 1864 | Ussuri, eastern China | HQ191428 8 | |

| SICH | C. n. sichuanicus Guo, Chen, Wang, 1978 | Sichuan, China | AY035876 1 | |

| TAIO | C. n. taiouanus Blyth 1860 | Taiwan | EF058308 14 | |

| PSEU | C. n. pseudaxis Eydoux and Souleyet, 1841 | Vietnam | AF291881 4 | |

| DYBO | C. n. dybowskii Swinhoe, 1864 | Manchuria | AF291880 4 |

- C. e., Cervus elaphus; C. c., C. canadensis; C. n., C. nippon; Acc. No., accession number; ref., reference. Species Authorities are adopted from Grubb 1993.

- 1Ludt et al. (2004); 2Lee MY, Kim YH, Lee JW (2013) (unpubl.); 3Zha D, Xing X, Yang F (2010) (unpubl.); 4Randi et al. (2001); 5Wada et al. (2007); 6Polziehn and Strobeck (1998); 7Polziehn and Strobeck (2002); 8Yu H, Li XP, Duan XP, Duan YJ (2010) (unpubl.) 9Tu JF, Xing XM, Yang FH (2009) (unpubl.); 10Zhou C (2014) (unpubl.); 11Kuwayama and Ozawa (2000); 12Han SH, Cho IC, Lee SS, Ko MS, Oh HS, Oh MY (2007) (unpubl.); 13Feng J, Li Y, Rittenhouse KD, Templeton JW (1995) (unpubl.); 14Chang HW, Wang HW, Tsai CL, Lin CY, Chou YC (2006) (unpubl.); 15This study.

Complete cytb was amplified and sequenced in two separate segments using both newly designed primers and primers published previously: cytb483_F (this study) and cytb3 (Kirstein and Gray 1996) for one segment, cytb_cerv (this study) and cytoB–B2 (Ludt et al. 2004) for the other. PCRs and sequencing of cytb were performed as for CR, but using 55°C as annealing temperature in the amplification profiles. All primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

The resulting sequences were aligned and edited using the multiple alignment program included in the package Vector NTI v. 9.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the software BioEdit (Hall 1999). To ensure that our sequences were not contaminated by Numts of nuclear origin, we verified their mitochondrial authenticity by comparing the internal organizations of the entire CR and cytb with data reported for Cervids (Douzery and Randi 1997; Ludt et al. 2004). Since the sequences used were partly obtained in this study and partly taken from the GenBank database (i.e. all the available sequences that covered the complete length for both markers), they corresponded to subspecies and individuals that were different for cytb and CR. Consequently, the two data sets have been analyzed separately. After inspection by eye, two contig alignments of 1132 and 963 nucleotides (nt) were obtained for cytb (AL1 in Supporting Information) and CR (AL2), respectively. The CR original alignment included 24 indels (10 of them were singletons), an additional insertion of a 77–80 base pair (bp) VNTR (Variable Number of Tandem Repeat) sequence that was absent in C. elaphus (C. e. bactrianus, C. e. yarkandensis and C. e. hanglu included) and some C. canadensis (C. c. kansuensis, C. c. macneilli, C. c. alashanicus, but cf. Randi et al. 2001). The phylogenetic value of VNTRs in Cervids is dubious (Randi et al. 2001). Therefore, the VNTR insertion as well as indels were removed. No gaps were observed in the cytb alignment. The HKY and GTR transition models of nucleotide substitution with a proportion of invariable sites (I) and rate heterogeneity among sites (G) with four categories were selected by jModeltest v. 0.1.1 (Posada 2008) as the best-fitting models for our cytb and CR alignments, using both the Akaike Information Criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc), and the BIC model. Each data set was analysed as a single partition. Exploratory phylogenetic trees were obtained to check for variation in substitution rates among branches, using mega v. 6.0 (Kumar et al. 2008) with the Neighbour-Joining (NJ) procedure under the TN93 genetic distance model (Tamura and Nei 1993). We focused our analyses on a Bayesian approach to infer the phylogenetic relationships of mitochondrial haplotypes and to date clade divergences using beast v. 1.8 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007; Drummond et al. 2012). After inspecting the results from NJ trees and performing a set of preliminary BEAST runs, a relaxed clock model, assuming uncorrelated rates of lineage variation drawn from a lognormal distribution to allow for lineage-specific substitution rates, was applied to the cytb data set. In pilot runs of CR alignment, the ‘ucld.stdev’ parameter distribution clumped around zero, suggesting clocklike data. Consequently, a strict clock model was selected in the final analysis. Three outgroup species (two sequences each from GenBank), Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758 (Accession numbers: DQ186269, EF693798), Muntiacus reevesi Ogilby, 1839 (EF035447, NC004069) and Dama dama (JN632629, AJ000022), were used to root the cytb tree by constraining the ingroup (all Cervus sequences) to be monophyletic. To reduce artefacts due to saturation or long branches, and since the data set had no need to be polarized, no outgroup was used for the reconstruction of the CR tree. We applied a mutation rate of 0.0111–0.0131 substitutions per site per Myr within lineages to the CR sequences (Randi et al. 2001) and included uncertainty by providing a normal prior distribution on the ‘clock.rate’ parameter (mean of the branch rates), using either the slower (mean = 0.0111, SD = 0.0011) and faster (mean = 0.0131, SD = 0.0013) substitution rate. Conversely, a conservative uniform prior distribution (with 0 and 1 as extreme values) on ‘ucld-mean’ was retained for cytb sequences, given the lack of consistent rate values from different studies (e.g. Ludt et al. 2004; Skog et al. 2009). Estimated base frequencies and a Yule process speciation tree prior were used to analyse both mitochondrial markers, as suggested for species-level phylogenies (Heled and Drummond 2012).

Molecular dating

Divergence times of phylogenetic clades for the cytb data set were calibrated using fossil data at two points: one point was the root of the tree at 25.8 Myr (normal distribution prior, SD = 3) as the TMRCA (time to the most recent common ancestor) of Bovids and Cervids (Hernández Fernández and Vrba 2005; cf. also Vrba and Schaller 2000; Hassanin and Douzery 2003; Hassanin et al. 2012), while the other was the first internal node at 10 Myr (normal distribution prior, SD = 1), which is the approximate date of the oldest fossil record of muntjac found in the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau (Dong 2007). The Dama node was not calibrated due to ambiguity of fossil records or molecular-derived dating (cf. Kuwayama and Ozawa 2000; Ludt et al. 2004; Pitra et al. 2004; Gilbert et al. 2006). Monophyly was enforced on the node leading to the Cervus species, based on results from our NJ tree and previous published data (Randi et al. 2001; Ludt et al. 2004). A date estimate for the Cervus node was derived from our cytb tree at 5.9 Myr (see 3), and then, it was incorporated as calibration point in the CR analysis, using a normal distribution prior for the ‘treeModel.rootHeight’ parameter in the BEAST algorithm. Two independent runs of 3 × 107 generations each were performed to check for convergence, with trees and parameters logged every 3000 generations to bring the effective sample sizes (ESSs) >400 for each individual parameter in the analysis. Tracer v. 1.6 was used to check for convergence of parameters and evaluation of the results. LogCombiner combined the two replicates, discarding the initial 10% of trees as burn in. The results were summarized and visualized by TreeAnnotator and FigTree v. 1.4.0, respectively. We evaluated the effective priors by running analyses without the sequences to ensure that posterior distributions were obtained mainly by our data sets rather than being heavily due to the prior setting. The program DNAsp v. 5 (Rozas et al. 2003) was used to calculate sequence divergence, π, and pairwise nucleotide divergence with Jukes–Cantor correction, pd (Nei 1987), between the (sub)clades/haplogroups identified in the phylogenetic Bayesian analysis.

Results

Coalescent phylogenetic analysis

The final cytb alignment (1132 nt) consisted of 37 different Cervus sequences, and the CR alignment (859 nt, excluding sites with gaps and VNTR insertion) comprised 38 sequences. Newly determined sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers indicated in Table 1. Details on sequence diversity are available as SM1 in Supporting Information.

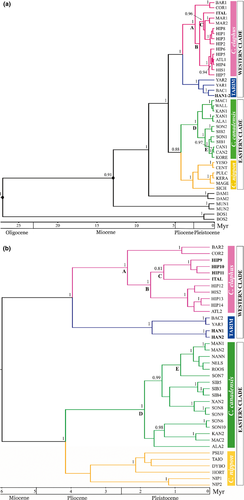

All statistics from the Bayesian analyses of cytb and CR data sets yielded the number of effectively independent draws from the posterior in the sample (ESS scores for all parameters >400 and >1000, respectively) and trace plots of posterior probability estimates that indicated adequate chain mixing and convergence for all runs. Runs using slower and faster substitution rates for the CR priors yielded nearly identical results. Gene trees inferred from both mitochondrial markers produced strongly concordant topologies, with the CR phylogeny showing slightly higher resolution at some inner nodes. Both trees showed two robustly supported (100% posterior probability) monophyletic clades (Fig. 1a,b) that clearly separate a western red deer cluster of haplotypes from Europe, North Africa, Middle East and central Asia on one hand (Western Clade), and an eastern cluster of haplotypes from eastern Asia and North America on the other (Eastern Clade). Within the Western Clade, two subclades are in turn well differentiated and statistically highly supported: one comprising haplotypes of red deer populations from central Asia (Tarim group), including C. e. bactrianus, C. e. yarkandensis and C. e. hanglu, while the other grouping haplotypes of C. elaphus from Europe, North Africa and Middle East. Pairwise distances (pd) between the two subclades (0.0432, SD 0.0074 and 0.0567, SD 0.0111 for cytb and CR, respectively) are slightly lower than the values between the two major clades (0.0572, SD 0.0043 for cytb and 0.0781, SD 0.0060 for CR). Differently from what we obtained in the cytb tree (Fig. 1a), the Tarim group subclade was highly resolved in the CR phylogeny (Fig. 1b), where a clear segregation of haplotypes of Kashmir red deer (HAN1,2) from those of C. e. bactrianus (BAC2) and C. e. yarkandensis (YAR3) is evident, with robust support (100% posterior probability).

Within the C. elaphus subclade, the lineages leading to the Barbary red deer from Tunisia, Cervus elaphus barbarus, and to the Tyrrhenian red deer from Sardinia/Corsica, Cervus elaphus corsicanus, (node A, Fig. 1) are basal, showing pd values from the other C. elaphus sequences of 0.0217 (SD = 0.0052) for cytb and 0.0370 (SD = 0.0104) for the CR. A western lineage and an eastern lineage (node B, Fig 1) of haplotypes are also apparent for red deer from central-western Europe and eastern Europe/Middle East, respectively, separated by mean pairwise distances of 0.0194 (SD = 0.0040) for cytb and 0.0251 (SD = 0.0072) for CR. Noteworthy that haplotypes referable to the Cervus elaphus hippelaphus subspecies are not monophyletic, belonging to both western and eastern subclades. Interestingly, values of pd = 0.0234 (cytb, SD = 0.0062) and 0.0238 (CR, SD = 0.0075), comparable with those of the C. e. corsicanus/C. e. barbarus lineage, are observed for the private unique haplotype of red deer Cervus elaphus italicus Zachos, Mattioli, Ferretti, Lorenzini, 2014 from Bosco della Mesola Natural Reserve (falling into the eastern lineage in our cytb and CR trees, node C, Fig. 1), the only extant population allegedly native to the Italian peninsula.

In the Eastern Clade, two sister subclades corresponding to C. nippon and C. canadensis are well separated, showing pd distances of 0.0400 (cytb, SD = 0.0063) and 0.0588 (CR, SD = 0.0079), which are very similar to the corresponding values of the Western subclades. Our tree reconstructions did not allow any inference about possible phylogenies or segregation of haplotypes according to geography within the C. nippon subclade, except for a rough distinction between sequences from continental (SICH) and island (YESO, CENT, PULC, KERA, MAGE) populations in the cytb tree. Many sequences should probably be analyzed from different locations to get evidence of lineage differentiation. Unfortunately, they were not available either from our sampling or as cytb and CR complete sequences from public databases. Sometimes, geographical origins of published sequences are not even mentioned (cf. haplotypes NIP1,2 in our CR tree). Within C. canadensis, no distinction between North American and Asian haplotypes (together referred to as wapiti, see below) was evident from both trees (node E, Fig. 1). By contrast, Asian wapiti seems to be non-monophyletic, falling into two well-distinct lineages which showed pd values of 0.0172 (SD 0.0039) and 0.0268 (0.0047), respectively, for cytb and CR (node D, Fig. 1).

Divergence time estimates

Molecular and fossil data were used to derive the posterior distribution of divergence dates for the crown (sensu De Queiroz 2007) Cervus in the cytb tree. We calibrated the root age (TMRCA of Bovids and Cervids) to 25.8 ± 3 Myr, and the time of the oldest muntjac fossil to 10 ± 1 Myr. Estimates of TMRCA and 95% highest posterior densities (HPD) for the major Bayesian phylogroups are shown in Table 2. Running the same analyses (with the same settings) without sequences confirmed that our data rather than the priors were responsible for the resultant dates. However, our divergence dates were associated with rather broad ranges of 95% posterior density intervals (Table 2), and consequently, the calculated times can only be considered as rough estimates. Yet, large credible intervals are expected when estimating divergence times from sequence data owing to time and lineage-dependent variation of mutation rates.

| Groups | cytb | CR |

|---|---|---|

| Dama/Cervus | 8.4 (3.7–13.5) | |

| Western/Eastern Clades | 5.9 (2.6–9.7) | 6.0 (4.6–7.4) |

| Tarim/C. elaphus subclades | 4.0 (1.7–6.9) | 4.0 (2.9–5.1) |

| C. nippon/C. canadensis subclades | 4.3 (1.7–7.3) | 4.2 (3.2–5.2) |

| C. e. corsicanus (barbarus)/C. elaphus lineages (node A) | 2.4 (0.9–4.5) | 2.4 (1.7–3.0) |

| C. canadensis lineages (node D) | 2.1 (0.7–4.1) | 1.9 (1.3–2.4) |

| C. e. italicus/C. elaphus lineages (node C) | 1.4 (0.4–2.5) | 1.3 (0.8–1.8) |

According to our cytb tree, the divergence between Dama and Cervus would have occurred at approximately 8.4 Myr (95% HPD 3.7–13.5), while the split between the two major Cervus clades can be estimated at around 5.9 Myr ago (95% HPD 2.6–9.7). This last dating was subsequently used as root calibration point for the CR phylogenetic reconstruction, following a Bayesian argument that a posterior of today is the prior for tomorrow. Coalescent analyses of both markers yielded consistent average values of dating, although the CR tree showed node intervals that were narrower than those from cytb tree, possibly due to a higher number of informative sites included in the CR data set. Our phylogenetic reconstruction indicates that two main phases can be recognized during the diversification of Cervus. The first evolutionary event was the divergence from a common ancestor of the Western and Eastern main clades, occurred approximately 6 Myr ago, while the second involved the separation of two subclades in the Western Clade (i.e. the Tarim group on one hand and the remaining C. elaphus subspecies on the other) and between C. nippon and C. canadensis subclades of the Eastern Clade, which took place nearly simultaneously, some 4 Myr ago. Interestingly, populations of the Tarim group are molecularly as old as the C. nippon group, with a differentiation dating back to the middle Pliocene. Radiation within each of the four subclades occurred at approximately 2 Myr, except for C. nippon, which split earlier, around 3.5–2.5 Myr ago. Within the C. elaphus subclade, the C. e. corsicanus/C. e. barbarus lineage, and the C. e. italicus haplotype diversified more recently, nearly 2 and 1 Myr ago, respectively.

Discussion

Phylogenetic analysis of Cervus and taxonomic considerations

The phylogeny of Cervinae has been extensively addressed, albeit with a sampling scheme largely focused on Europe, fairly on eastern Asia, but scarcely on central Asia (Polziehn and Strobeck 1998, 2002; Randi et al. 2001; Mahmut et al. 2002; Ludt et al. 2004; Pitra et al. 2004; Gilbert et al. 2006). Our investigation is the first one where mitochondrial complete cytb and CR sequences are analyzed under a Bayesian coalescent framework to derive phylogeny and divergence date estimates for most of the Cervus species, with attention on populations from central Asia.

Both mitochondrial markers used in this study yielded highly supported trees and strongly concordant topologies, with comparable proportions of genetic distances and molecular datings. Our phylogenetic reconstruction confirms that red deer is differentiated into two robust monophyletic clades (Randi et al. 2001; Polziehn and Strobeck 2002; Ludt et al. 2004; Pitra et al. 2004), covering approximately the western and eastern part of the distribution. Molecular results also suggest the classification of Cervus into four different species corresponding to (1) the western red deer C. elaphus, present in Europe, North Africa and Middle East, probably with Iran and western Russia as its easternmost limit (cf. Meiri et al. 2013), (2) the eastern wapiti [as Pitra et al. (2004) proposed to name the whole group] C. canadensis, dwelling from central to eastern Asia and North America, (3) the sika deer C. nippon inhabiting north-eastern Asia and Japan, and finally, (4) the Tarim red deer present in central Asia (approximately Yarkand-Tarim and Bukhara regions, and Indian Kashmir). The last ones were hitherto considered as C. elaphus subspecies (C. e. yarkandensis, C. e. bactrianus, and C. e. hanglu, respectively), but, according to our results, they are worthy of being raised to the rank of valid species. We suggest to call them Cervus hanglu Wagner, 1844 (so named throughout the discussion), since this is the name with a priority over C. yarkandensis Blanford 1892, and C. bactrianus, Lydekker 1900. Hangul (or Kashmir red deer) is poorly known at the molecular level. Mitochondrial markers had never been studied so far in this population, and their phylogenetic relationships were totally unknown. A microsatellite-based study has been published recently, revealing low genetic variability and high inbreeding for the population of Dachigam National Park, the last surviving nucleus of Kashmir red deer (Mukesh et al. 2013). Based on our genetic results, this deer clearly belongs to the species C. hanglu (our nomenclature), although being distinct from Cervus hanglu bactrianus/Cervus hanglu yarkandensis (that are clearly synonyms), as suggested by a highly resolved node in the CR tree.

Since single gene trees might not be representative of organismal phylogenies (Zachos 2009 and references therein), we are aware, indeed, that our taxonomic suggestions need support from further molecular sources in addition to cytb and CR, for example mitogenomics and nuclear coding genes, as well as confirmation from morphology of extant and museum specimens.

Our data do not support morphology-based subspecific taxonomy within the C. elaphus subclade (e.g. Groves and Grubb 1987, 2011) and confirm the results from previous molecular studies (e.g. Ludt et al. 2004). However, our trees show three genetic lineages that are clearly differentiated with a rough underlying geographical structure: one distributed mainly in central-western Europe (but present also in Ukraine), another dwelling from eastern Europe to Middle East, and a third lineage corresponding to C. e. corsicanus and C. e. barbarus from Sardinia and North Africa. These last deer should be considered as a single subspecies, named C. e. corsicanus Erxleben, 1777, due to priority of time over C. e. barbarus Bennett, 1833. The western and eastern C. elaphus lineages are consistent with isolation and recolonization from different Pleistocene refugia during the Last Glacial Maximum (Sommer et al. 2008; Skog et al. 2009). The position of haplotype HIP7 from Ukraine in the western lineage on the cytb tree is somewhat puzzling, even though Niedziałkowska et al. (2011) reported that the western lineage extends far eastward, up to eastern Belarus. Possibly, a misattribution of accession number in GenBank or sampling location occurred in the original paper (the sequence was deposited, unprovided with geographical provenance, as C. e. hippelaphus, although it was indicated as Cervus elaphus brauneri Charlemagne, 1920, from Ukraine in the text; cf. Table 1 in Ludt et al. 2004). Alternatively, both the eastern and western C. elaphus lineages coexist in Ukraine (Kuznetsova et al. 2012). Artificial translocations with red deer of the eastern lineage (e.g. Cervus elaphus maral from Caucasus) cannot be excluded either (S. Mattioli pers. comm; Kuznetsova et al. 2012). Our results are in good agreement with Skog et al. (2009): based on a 332-bp fragment of the mitochondrial CR, and wide sampling of European red deer, these authors concluded that most of the current C. elaphus subspecies (with the exception of C. e. corsicanus) were not supported by their mitochondrial data. Polyphyly of C. e. hippelaphus from our results also suggests that subspecific classification of C. elaphus should be very much revised.

One interesting outcome of our study concerns the phylogenetic placement of the small population from Bosco della Mesola Natural Reserve that represents the only red deer native to mainland Italy, after the disappearance of the species at the beginning of the 19th and 20th centuries, respectively from the Apennines and the Alps. Previous molecular studies (Lorenzini et al. 2005; Skog et al. 2009) did not provide safe conclusions about the assignment of Mesola haplotype to the western or eastern C. elaphus lineage or, alternatively, to an intermediate lineage (Sommer et al. 2008), due to low support of their phylogeny. Here, we show that it clearly occupies a well-supported position as sister lineage to the eastern C. elaphus (of which it might represent the ancestral gene pool, as suggested by palaeontological data, cf Sommer et al. 2008) both in the cytb- and CR-based phylogenies, and we provide support for its subspecific status, C. e. italicus (Zachos et al. 2014). Mesola red deer may well represent a drift-caused refugial lineage of eastern origin, which was widespread in the Italian peninsula prior to the fragmentation due to the climatic oscillations of the Pleistocene, and, ultimately, to the extinction of native populations caused by human activities.

The Eastern Clade comprises two well defined species, the sika deer group from eastern Asia, identified as C. nippon, and the wapiti group, C. canadensis, from central-eastern Asia and North America. Our data, however, do not allow inferences at the subspecific level for any of the two species, owing to the lack of a wide sampling scheme, as a phylogenetic study of species with such vast distributions would require. Similarly, a clear geographical delimitation of intraspecific genetic lineages is hazardous with our data. As an example, while the cytb tree identified at least two geographical haplogroups, the North Asian/North American and the South-Eastern Asian (node D, Fig. 1a), conversely, the CR tree no longer maintained this subdivision and placed, for example, a polyphyletic Cervus canadensis songaricus from northern Asia also in the South-Eastern haplogroup (node D, Fig. 1b, SON6, SON10). It should be said, however, that any conclusion regarding these sequences must be drawn with caution, since their geographical origin is unknown (see Table 1), and an incorrect subspecific assignment cannot be ruled out. Despite these caveats, current subspecific classification of C. canadensis seems not to be justified by our molecular data. To reconcile taxonomy and phylogeny, the number of subspecies should probably be reduced, to provide them with an underlying genetic background, congruent with their geographical distribution and morphological differentiation.

The high sequence variation observed for C. nippon haplotypes, as revealed particularly by the CR tree, might be explained by the island distribution of many populations, although their isolation from mainland counterparts seems to be not as recent as that suggested by Ludt et al. (2004).

Timing of species divergence

A date for the divergence of Dama was obtained in the late Miocene, at 8.4 Myr, in fairly good agreement with Randi et al. (1998, 2001), Hassanin and Douzery (2003); Ludt et al. (2004), Hughes et al. (2006), but in contrast with Pitra et al. (2004), that dated back the fallow deer to a much younger time at approximately 5 Myr (but see Ludt et al. 2004). Neither datings, however, can be supported by fossils: the first form really referable to the genus Dama goes back only to the middle Pleistocene (Di Stefano and Petronio 2002).

Coalescent Bayesian analyses of our cytb and CR data sets yielded highly consistent divergence times for the Cervus species. The most recent common ancestor between Eastern (C. canadensis and C. nippon) and Western (C. elaphus and C. hanglu) Clades may have occurred in the late Miocene, at a mean age of approximately 6 Myr. This estimate is consistent with molecular results (Randi et al. 2001; Ludt et al. 2004; Hughes et al. 2006), and roughly concordant with palaeontological evidence, according to which the most ancient fossil referable to the genus Cervus, C. magnus from China, dates back to the early/middle Pliocene (Di Stefano and Petronio 2002). The split within the two main Clades in the middle Pliocene (at approximately 4 Myr) might be related to allopatric speciation due to strong geographical barriers, such as the mountain chains of central Asia (e.g. Tian Shan, Pamir, Kunlun), and an increasing aridity of the Tarim Basin following the formation of the Taklimakan desert, which occurred as early as 5.3 Myr ago (Sun et al. 2008). After this separation, the red deer experienced a phase of intense radiation during the late Pliocene/early Pleistocene (3–2 Myr ago), suggesting that Plio/Pleistocenic climatic oscillations may have played a significant role in the diversification and phylogeography of red deer species. By the early Pleistocene (2.5 Myr ago, after Gibbard et al. 2010), intraspecific differentiation and dispersion occurred nearly simultaneously for populations of C. elaphus, C. hanglu, C. nippon and C. canadensis, as endorsed also by their comparable genetic distances. From then on, their evolutionary histories were driven by Quaternary oscillations of glacial and interglacial periods, associated with the existence of refuge areas and the occurrence of isolation, expansion and recolonization events, which, eventually, led to the current geographical distribution of the extant genetic lineages (cf. Skog et al. 2009).

Biogeography and evolutionary patterns

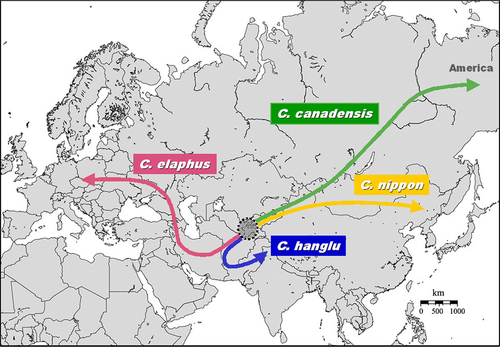

Our Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction, along with the relevant geological information, suggests that evolutionary events and dispersal for the tribe Cervini might have occurred as follows (Fig. 2). After splitting from its sister lineage Dama in the mid–late Miocene, the ancestors of the extant Cervus species appeared at the late Miocene somewhere in central Asia. In this and other Earth's areas, an environmental change had occurred between the Oligocene and Miocene, when a cooler and drier climate led to the replacement of forest habitats, typical of an earlier warmer period, with open grasslands (Meijaard and Groves 2004), thus favouring the radiation and dispersion of many pecoran families (Hassanin and Douzery 2003). Subsequently, two genetic lineages, corresponding to our Western and Eastern Clades, diverged and migrated, almost synchronously, one lineage westward, towards the Middle East and then Europe, the other eastward, where in turn the C. nippon sublineage soon differentiated southward, while C. canadensis followed a northward route. Asian wapiti colonized North America via the intermittent land bridge of Beringia in the late Pleistocene (cf. Meiri et al. 2014), and a continuous gene flow between Asian and North American populations occurred probably up to the last raising of the sea level and the formation of Bering Strait, some 11 000–9000 years ago (Vislobokova and Tesakov 2013; Meiri et al. 2014). This is in line with the lack of genetic differentiation between Asian and American wapiti found in this and previous studies (Kuwayama and Ozawa 2000; Randi et al. 2001; Polziehn and Strobeck 2002; Hassanin and Douzery 2003). Similarly, the C. elaphus and C. hanglu sublineages of the Western Clade separated early in the mid Pliocene, the first migrating from its centre of origin westward, to western Asia, reaching eventually the westernmost areas of Europe and North Africa. The second sublineage, C. hanglu, after a short migration eastward, remained isolated west of the Tarim Basin, unable to cross the Taklimakan desert, and/or the Pamir Plateau, Tian Shan and Kunlum Mountains, that surrounded the Basin with peaks exceeding 7000 m a.s.l., after completion of their orogeny during middle Miocene times (Yang et al. 2014). Diversification within the C. hanglu sublineage may have occurred due to glacial fragmentation and subsequent recolonization events in the early/middle Pleistocene, similarly to other species that currently live around the Basin, for example the Yarkand hare Lepus yarkandensis (Shan et al. 2011), and Agamid lizard Phrynocephalus axillaris (Zhang et al. 2010). In contrast to our reconstruction, previous morphology-based analyses suggested that C. hanglu red deer would derive from C. elaphus populations dispersing eastward through the Middle East during the middle Pleistocene (cf. Mahmut et al. 2002).

According to our evolutionary scenario, it does not appear that the Eastern Clade, that is C. canadensis and C. nippon, is an offshoot that split off from the Western Clade, rather it represents a lineage that diverged early from a common ancestor, simultaneously (not afterwards) to the Western Clade. As a consequence, there is no molecular evidence that sika deer-like are the ancestors of C. elaphus, as suggested previously (Geist 1987; Kuwayama and Ozawa 2000; Di Stefano and Petronio 2002). Second, the C. hanglu sublineage (Kashmir red deer included) is not basal in the Cervus phylogeny (as shown in Ludt et al. 2004). This excludes the most ancestral status for this genetic lineage, despite its current distribution probably being the area closest to the geographic origin of genus Cervus. Geographical proximity of highly divergent genetic lineages, such as C. hanglu and C. c. songaricus, or C. canadensis sibiricus, or C. canadensis wallichi, may depend on movements of populations that occurred after their differentiation, rather than being due to their recent common origin.

Implications for conservation

The red deer is overall classified as a ‘Least Concern’ species by the IUCN, with only few subspecies listed as ‘threatened’ (http://www.iucnredlist.org, accessed on 27.11.2014). C. e. bactrianus and C. e. hanglu (C. h. bactrianus/yarkandensis and C. h. hanglu according to our nomenclature) are not even mentioned, nor is their conservation category indicated. They only appear in Appendix II (as C. e. bactrianus) and Appendix I (as C. e. hanglu) of CITES. Nevertheless, hangul from the Jammu and Kashmir State of India is on the brink of extinction, and only several hundred individuals still existed in 2011 (Shah et al. 2011).

Although taxonomical nomenclature is presently subjected to a hot debate regarding the criteria for species splitting according to the Biological Species Concept versus the more recent so-called Phylogenetic Species Concept (e.g. Groves and Grubb 2011; Frankham et al. 2012; Zachos et al. 2013), several genetically discrete populations of red deer require urgent protection measures, whatever their specific or subspecific names. In conservation, the current emphasis given to specific names leads either to the often unwarranted promotion of subspecies to species level, or to the ignorance of subspecific, interfecund populations, which may thus become extinct. Both approaches are questionable, but for different reasons. As to red deer, the conservation status and legal listing of all Tarim populations (C. h. hanglu, C. h. bactrianus/yarkandensis) will need to be (re)assessed. Furthermore, given their geographic proximity with genetically highly divergent populations (e.g. C. c. wallichi, C. c. sibiricus, C. c. songaricus), care should be taken to prevent introgression whenever translocations for conservation and/or management purposes are planned.

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Novelletto for introducing us to the use of BEAST. F. E. Zachos kindly revised an earlier version of the manuscript. We are indebted to S. Mattioli for his valuable suggestions, encouragement, and for providing some of the references. We also thank two anonymous reviewers and the Editor-in-Chief of JZSER for improving the manuscript.