Prevalence and associations of self-reported sleep problems in a large sample of patients with Parkinson's disease

Summary

Sleep problems are important comorbid features of, and risk factors for, neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease (PD). To assess the prevalence and associations of sleep problems in patients with PD we analysed data from almost 54,000 participants in the Fox Insight study, including data from 38,588 patients with PD. Sleep problems are common in PD, with ~84% of respondents with PD reporting difficulty falling or staying asleep. Experiences of insomnia, restless leg syndrome, vivid dreams, acting out dreams, and the use of sleep medication are over-represented in patients with PD compared with matched healthy controls. Male sex and PD onset before the age of 50 were also associated with a greater risk of sleep problems. A physician diagnosis of insomnia was associated with more symptoms of depression, impairment of cognition-dependent independence, and a lower quality of life. Sleep problems were also associated with a higher prevalence of OFF periods compared with PD patients without sleep problems. 6.7% of PD patients endorsed sleep complaints as their most bothersome symptom, and reported non-specific poor sleep quality as the most common sleep problem. These patients also had a better quality of life and lower depression and cognitive impairments than patients for whom postural instability was their most bothersome symptom, indicating the relative burden of sleep problems is contextualised by the severity of motor symptoms. Overall, these findings reinforce the high prevalence of sleep problems in a very large sample of PD patients, and indicate important associations of sleep problems with daily function and quality of life in PD.

1 INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common age-related neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system, estimated to currently affect over six million people worldwide (Bloem et al., 2021). The presentation of PD can be varied, but the most common symptoms of PD include motor system manifestations such as bradykinesia, postural instability, and tremor, as well as non-motor symptoms such as cognitive impairments, low mood, and gastrointestinal dysfunction (Bloem et al., 2021; Poewe et al., 2017). The pathological hallmarks of PD consist of degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain substantia nigra and dysfunctions of dopaminergic terminals in other brain regions and a wide range of environmental and genetic factors leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and Lewy body formation are implicated in the pathogenesis (Simon et al., 2020).

Sleep disturbances have long been linked to PD, with initial reports focussing on the manifestation of sleep problems in established disease (Bollu & Sahota, 2017). Sleep problems that have been described in PD include excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), sleep attacks, insomnia (which may be partially linked to night-time motor symptoms), sleep-related breathing disorders, parasomnias, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, and restless leg syndrome (Thangaleela et al., 2023). The presence of sleep disturbances in PD is believed to increase the disease burden and adversely to impact the quality of life (Liguori et al., 2021). However, there is a well-established link between prodromal REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder (RBD; characterised by dream enactment in parallel with a loss of muscle atonia during REM sleep) and subsequent PD motor symptoms that may follow over a period of approximately 20 years; the presence of RBD is estimated to increase the annual risk of PD by 6.3% and is understood to be indicative of the presence of synucleinopathy (Postuma et al., 2019). Other sleep disturbances may progress in severity with the clinical course of Parkinson's disease, and may be particularly associated with other non-motor symptoms (Xu et al., 2022). There are a number of putative pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in sleep disturbances in PD, including alterations in brainstem monoaminergic systems implicated in sleep homeostatic control, degeneration of hypothalamic orexinergic neurones, circadian rhythm dysfunction, nocturnal manifestations of PD motor symptoms such as rigidity and akinesia, autonomic dysfunction and links between increased depression and anxiety symptoms and insomnia (Asadpoordezaki et al., 2023; Thangaleela et al., 2023).

The current study aimed to describe the prevalence of sleep problems in a large cohort of patients with PD, and to compare such with age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Further, we aimed to examine if early disease onset was associated with more frequent sleep problems. We also wished to examine the associations between sleep problems in PD and mood, cognition, and quality of life and as well as in the frequency and severity of OFF periods. Finally, we aimed to examine the relative ranking of sleep problems in the context of all PD symptoms, and to explore if there were specific features of patients for whom sleep problems were their most bothersome symptoms.

2 METHODS

Fox Insight is an online study conducted by the Michael J. Fox Foundation wherein different PD-related online questionnaires are completed by PD patients (n = 38,588) and healthy control volunteers (n = 15,832) (Smolensky et al., 2020; https://www.michaeljfox.org/fox-den). Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Fox Insight database (https://foxinsight-info.michaeljfox.org/insight/explore/insight.jsp) on 10/06/2023. For up-to-date information on the study, visit https://foxinsight-info.michaeljfox.org/insight/explore/insight.jsp. All participants granted informed consent for participation in the study, and the Fox Insight study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (IRB#120160179). Eligible participants were English-speaking individuals aged 18 and above who were recruited through various channels (social media, newsletters, research events, clinician referrals; Smolensky et al., 2020). Within the study there were core sets of questionnaires that all participants completed as relevant to their PD status, and additional questionnaires applied to subsets of participants. There were a mix of longitudinal and one-off items, and repeated measures were elicited every 3 months from the relevant participants.

The questionnaire and response items included in the current study are listed in Table S1. The majority of the items assessed had a dichotomous response format (e.g. “Insomnia: Has a physician diagnosed you with this condition? No/Yes”). Validated psychometric scales were applied to subsets of participants: the 8-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-8) was used as an indicator of quality of life (QoL) in patients with PD (Huang et al., 2011); the Penn Parkinson's Daily Activities Questionnaire-15 (PDAQ-15), a 15-item measure of cognitive instrumental activities for daily living for PD patients (Brennan et al., 2016); and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to assess symptoms of depression (Yesavage et al., 1982).

Following the approval of our application for access to data by the Fox Insight Data and Publications Committee, data were downloaded (June 2023) and the dictionary of data was explored carefully and the relevant variables pertinent to sleep were selected and imported into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0). For data from health and medical questionnaires with multiple iterations, data aggregation was executed based on the maximum values for each response per participant (e.g. their age as per the most recent data entry point). Continuous variables were characterised using mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as counts (percentage). To account for varying participant numbers in different questionnaires, the results were expressed as a percentage of relevant respondents for each item. Comparisons of means or medians for continuous variables in groups or subgroups of participants were assessed using either t-tests or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate to the dependent variables. Chi-square and design-based F tests as appropriate were applied to explore associations between categorical variables. Logistic regression models were constructed to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). These models were run with predictor variables which had similar sample sizes to avoid loss of statistical power through the inclusion of independent variables with considerably smaller sample sizes. For case–control analysis, due to imbalances between the PD and control groups in the full study cohort regarding sex and age (Table S1), propensity matching was used to create matched groups for analysis. For sex and age matching cases and controls for between group analysis, propensity matching via the FUZZY package in SPSS was used with a toleration of 1 year of age for case–control matching. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 29.0 and a threshold of p less than 0.0001 was applied to account for the high level of statistical power afforded by the large sample and correction for multiple comparisons. Further to this, and to help in the interpretation of the results and distinguish between statistical and clinical/practical significance, indicators of effects size are presented as either Phi values for Chi Square and F tests, and Cohen's d for groupwise comparisons; these effect size indicators are interpreted according to Cohen (1988, 1992, Phi >0.1 <0.3 small effect, >0.3 <0.5 moderate effect; Cohen's d: 0.2 = small effect, 0.5 = moderate effect, 0.8 or higher = large effect). Groupwise differences were also interpreted according to the descriptive statistics presented.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics and participant characteristics

Parkinson's disease-related online questionnaires were completed by patients with PD (n = 38,588) and healthy controls (n = 15,832). In brief, 53.2% of participants were female, the average age was 66.95 years (SD = 12.44), and the mean age at diagnosis of PD was 60.46 years (SD = 10.95; the demographic profile of the whole sample can be found in Table S2). To account for the differences in age profile between PD and healthy control cohorts (mean age = 69.9 years for PD and 59.9 years for healthy controls), we created sex and age propensity matched groups to allow for between group comparisons; the demographic profile and descriptive statistics of these participants are detailed in Table 1.

| Sleep variable | PD cases (N = 12,243) | Healthy controls (N = 12,149) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years, (SD)) | 64.13 (10.97) | 63.06 (11.86) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 74.6% | 72.5% |

| Male | 25.4% | 27.5% |

| Age when PD was diagnosed (years, (SD)) | 55.67 (11.61) | |

| Age started PD medication (years, (SD)) | 56.07 (11.19) |

3.2 Sleep problems in PD patients compared with healthy controls

Patients with Parkinson's disease endorsed a very high rate of subjective sleep complaints manifested as difficulties falling or remaining asleep, more so than in the matched healthy controls (84.2% of PD patients vs 43.3% of healthy controls; Table 2). A significantly higher proportion of patients with PD also reported difficulty staying awake during the day, having vivid dreams, acting out their dreams, and using sleep medication than the healthy control cohort (Table 2).

| Sleep variable | PD | Control | χ2 | p value | Phi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep during nighta | 84.2% (N = 10,288) | 43.3% (N = 9705) | 723.7 | <0.0001 | 0.19 |

| Difficulty staying awake during daya | 39.6% (N = 10,280) | 20.1% (N = 9708) | 902.6 | <0.0001 |

0.21 |

| Vivid dream experiencea | 58.2% (N = 10,284) | 37.2% (N = 9699) | 884.1 |

<0.0001 | 0.21 |

| Acting out dreama | 52.2% (N = 10,284) | 20.6% (N = 9699) | 1887 | <0.0001 | 0.31 |

| Medication for sleep problemsb | 49.6% (N = 10,630) | 27.8% (N = 9608) | 649.2 | <0.0001 | 0.18 |

- a Data from the “Your non-movement experiences” questionnaire.

- b Data from the “Your Medications” questionnaire.

Logistic regression into the presence of a diagnosis of PD revealed that problems getting to sleep or staying asleep at night (aOR 1.29, 1.22–1.36), difficulty staying awake during the day (aOR 1.75, 1.65–1.85), acting out dreams (aOR 3.61, 3.41–3.83) and using medication for sleep problems (aOR 1.60, 1.52–1.69) all predicted a diagnosis of PD (Table 3).

| Sleep variable | B | SE | Wald | Sig | Exp (B) | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep during night | 0.25 | 0.03 | 78.52 | <0.0001 | 1.29 | 1.22–1.36 |

| Difficulty staying awake during day | 0.56 | 0.03 | 380.70 | <0.0001 | 1.75 | 1.65–1.85 |

| Acting our dreams | 1.29 | 0.02 | 1807.2 | <0.0001 | 3.61 | 3.41–3.83 |

| Vivid dream experience | −0.06 | 0.03 | 3.99 | 0.046 | 0.95 | 0.90–1.00 |

| Medication for sleep problems | 0.47 | 0.03 | 300.25 | <0.0001 | 1.60 | 1.52–1.69 |

With regards to specific sleep disorders, ~61% of patients with PD reported that they had experience of insomnia, although the rate of physician diagnosed insomnia in the PD group was not statistically significantly higher than in the control group (Table 4). The reported rates of experience and diagnosis of restless leg syndrome (RLS) did not differ statistically according to the stringent thresholds for significance applied, but a small effect of lower frequency of experience of sleep apnea was reported in the PD group compared with the healthy control participants (Table 4).

| Sleep variable | PD | Control | χ2 | p value | Phi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Insomnia experience |

60.9% (N = 1021) | 50.8% (N = 957) | 20.3 | <0.0001 | 0.101 |

| Insomnia diagnosis from a physician | 52.0% (N = 583) | 44.9% (N = 519) | 5.08 | 0.02 | 0.071 |

| RLS experience | 29.8% (N = 954) | 23.8% (N = 1022) | 9.06 | 0.003 | 0.068 |

| RLS diagnosis from a physician | 62.0% (N = 284) | 49.4% (N = 243) | 19.01 | 0.004 | 0.126 |

| Sleep apnea experience | 13.3% (N = 1021) | 20.1% (N = 955) | 19.9 | <0.0001 | −0.1 |

- Note: Data from the “Your medical history” questionnaire.

3.3 Sleep problems in PD according to the sex of participants

Binary logistic regression models were applied to the full sample (without propensity matching) to examine the association of sleep problems in PD cases with sex whilst adjusting for age. This analysis indicates that male sex shows moderate associations with insomnia experience (male sex: aOR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.22,1.42) and difficulty getting to sleep at night (male sex: aOR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.20,1.25) and minor associations with having sleep problems (male sex: aOR = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.05,1.09), experience of RLS (male sex: aOR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.03,1.23), and vivid dream experience in PD (male sex: aOR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00,1.04). Male sex was also associated with a slightly decreased difficulty in staying awake during day (male sex: aOR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.91,0.95) and acting out dreams (male sex: aOR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.89,0.93).

3.4 Sleep problems in early-onset PD versus typical-onset PD

We next examined the relative prevalence of sleep problems in patients with early-onset PD (age at diagnosis ≤50; ~17.5% of PD patients in the full data set) and those whose PD was diagnosed after the age of 50 years (typical-onset PD). The rate of insomnia experience, difficulty staying awake during the day, difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep at night, and vivid dream experience were significantly higher in patients with early-onset PD than in typical-onset PD, although the magnitudes of these differences were small (Table 5). Further, examining the age at diagnosis as a continuous scale variable revealed that participants who endorsed sleep problems had a diagnosis at a younger age (60.3 ± 0.07 years vs. 63.0 ± 0.15, p < 0.0001), although participants who had a physician diagnosis of insomnia did not differ in their ages at diagnosis compared with those without an insomnia diagnosis (57.8 ± 0.37 years vs. 58.2 ± 0.3 years, p = 0.43).

| Sleep variable | Early-onset PD | Typical-onset PD | χ2 | p | Phi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia experience | 62.4% (N = 474) | 53.9% (N = 2256) | 12.75 | <0.0001 | 0.06 |

| Insomnia diagnosis from a physician | 55.7% (N = 278) | 52.3% (N = 1216) | 1.11 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| RLS experience | 28.2% (N = 475) | 30.6% (N = 2252) | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| RLS diagnosis from a physician | 63.4% (134) | 64.2% (690) | 0.028 | 0.86 | 0.00 |

| Sleep apnea experience | 18.9% (N = 855) | 21.3% (N = 2393) | 2.14 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Difficulty staying awake during day | 47.8% (N = 4603) | 36.9% (N = 25,428) | 196.75 | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| Difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep at night | 86% (N = 4603) | 79.7% (N = 25,426) | 99.90 | <0.0001 | 0.05 |

| Vivid dream experience | 60% (N = 4601) | 55.2% (N = 25,423) | 37.15 | <0.0001 | 0.03 |

| Acting out dream | 53.5% (N = 4601) | 51.9% (N = 25,421) | 3.61 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Medication for sleep problems | 44.2% (N = 4926) | 43.1% (N = 25,728) | 1.38 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

Univariate binary logistic regression analyses between sleep problems and the age of onset of PD while controlling for sex confirmed that early-onset PD was associated with small-to-moderate increases in the odds of daytime sleepiness, difficulty falling or staying asleep, sleep medication use and experiencing vivid dreams, and with decreased odds of acting our dreams (Table 6).

| Sleep variable | B | SE | Wald | Sig | Exp (B) | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty staying awake during day | 0.35 | 0.04 | 102.51 | <0.0001 | 1.42 | 1.33–1.53 |

| Difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep | 0.41 | 0.05 | 63.92 | <0.0001 | 1.51 | 1.36–1.66 |

| Vivid dream experience | 0.17 | 0.04 | 18.01 | <0.0001 | 1.19 | 1.10–1.30 |

| Acting out dream | −0.31 | 0.04 | 57.59 | <0.0001 | 0.74 | 0.68–0.80 |

| Medication for sleep problems | −0.14 | 0.04 | 15.68 | <0.0001 | 0.87 | 0.81–0.93 |

3.5 The association of insomnia and sleep problems with depression, cognition, and quality of life in Parkinson's disease

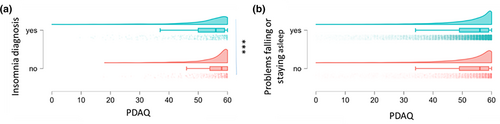

We next examined the associations between sleep problems and physician-diagnosed insomnia and on mental health and quality of life indicators in a subset of participants with PD who had reported mental health outcomes. Depression symptoms were measured with the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), the Penn Parkinson's Daily Activities Questionnaire (PDAQ) assessed daily function dependent on cognition, and the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-8) assessed quality of life. Multivariate analysis of variance using the GDS, PDAQ and PDQ-8 as dependent variables and the presence of problems falling or staying asleep as the independent variable revealed an effect of sleep problems (Wilk's lambda = 0.921, F(3, 24,002) = 689.5, p < 0.0001). Similarly, MANOVA with the presence of an insomnia diagnosis as the independent variable also revealed an effect (Wilk's lambda = 0.947, (F3, 1029) = 19.38, p < 0.0001). Probing these effects further, the average score on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was significantly higher (indicating more mood impairment) in PD cases with a diagnosis of insomnia than in PD patients without insomnia (5.61 ± 0.15 (N = 591) vs 4.47 ± 0.14 (N = 537) respectively, p < 0.0001, d = 0.40; Figure 1a), and in the larger cohort of PD patients who reported whether they had problems in getting to sleep or staying asleep, those who endorsed this had higher scores on the GDS than those who did not (5.32 ± 0.027 (N = 20,672) vs 3.81 ± 0.049 (N = 5039), p < 0.0001, d = 0.32; Figure 1b).

The PDAQ scores were significantly lower (indicating more impairment of cognition-dependent independence) in patients with PD who had a diagnosis of insomnia compared with PD patients with no diagnosis of insomnia (52.0 ± 0.40 (N = 653) vs 54.0 ± 0.27 (N = 607) respectively, p < 0.0001, d = 0.39; Figure 2a). However, PD patients who self-reported problems falling or staying asleep did not differ on PDAQ compared with PD patients who did not endorse those sleep problems (51.87 ± 0.07 (N = 22,284) vs 51.56 ± 0.14 (N = 5288) respectively; p = 0.47; Figure 2b).

The PDQ-8 scores were significantly higher (indicating less QoL) in PD patients who had a diagnosis of insomnia versus PD patients with no diagnosis of insomnia (14.40 ± 0.23 (N = 694) vs 12.07 ± 0.25 (N = 646), respectively, p < 0.0001, d = 0.39; Figure 3a). Further, in the larger cohort of PD patients who reported whether they had problems getting to sleep or staying asleep, those who endorsed this had higher scores on the PDQ-8 than those who did not (12.12 ± 0.04 (N = 23,231) vs 8.13 ± 0.07 (N = 5669), p < 0.0001, d = 0.68; Figure 3b).

3.6 Associations of sleep problems with OFF periods in PD

The OFF periods, during which medication effects wear off resulting in an exacerbation of motor symptoms, are common features in Parkinson's disease: 56.9% of PD patients in the current database who were asked about OFF periods (N = 7919) reported experience of OFF episodes. In smaller samples with the requisite data, 48.3% of PD patients (N = 526) believed that they have sleepiness during the OFF periods, although 75% of caregivers (N = 140) reported sleepiness in OFF states in PD patients whom they care for 95% of PD patients with OFF episodes experience reported that sleepiness during the OFF-state affects their daily life, and 5.5% of this population reported that sleepiness during the OFF-state severely impacts their daily life. The presence of sleepiness during OFF episodes not only affects the daily life of PD patients but also affects the daily life of caregivers, as 81.9% of caregivers believed that sleepiness in PD patients in the OFF state impacts their daily life.

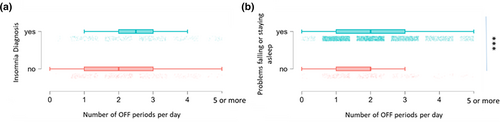

We next examined the association between the OFF state experience and sleep problems, using the classifier of “difficulty with falling asleep or staying asleep in the last month” to give the largest sample of PD patients with a reported OFF period status (N = 7916). 38.7% of participants without sleep problems experienced OFF periods whilst 58.8% of participants with sleep problems experienced OFF periods; p = 0.0001 by Chi square test for independence. When parsed by the presence of an insomnia diagnosis (total sample N = 1062), participants with PD and insomnia were not statistically more likely to experience OFF periods than PD patients without insomnia (71.9% of PD patients with insomnia experience OFF periods versus 64.7% of PD patients without insomnia; p = 0.012 by Chi square test for independence). The presence of a diagnosis of insomnia was also not associated with a greater duration of OFF periods or the number of hours spent in OFF periods (N = 727). The presence of an insomnia diagnosis being associated with more OFF periods per day did not reach the threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.002) (Figure 4). The presence of sleep problems (falling or staying asleep) was associated with more hours spent in OFF periods (p < 0.0001) and a greater number of OFF periods per day (p < 0.0001; Figure 4).

3.7 Examining the subjective ranking of sleep disturbance as a symptom in PD

Participants with PD ranked their PD symptoms as between their most bothersome symptom and their fifth most bothersome symptom. Postural instability was the most frequently endorsed most bothersome symptom (~23% of relevant participants). Sleep complaints were endorsed as the most bothersome symptom by 6.71% of respondents (Table 7). Of the sleep complaints endorsed by participants who ranked sleep problems as their most bothersome symptom, unspecified poor sleep quality was the most common (endorsed by ~55% of relevant patients; Table 8). Of these participants, ~22% reported at least two different types of sleep complaint, and ~11% endorsed at least three different sleep complaints.

| Most bothersome symptom | Frequency | % respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Postural instability | 10,637 | 22.88 |

| Tremor | 9160 | 19.7 |

| Cognitive decline | 5266 | 11.33 |

| Mood disturbances | 4548 | 9.78 |

| Fatigue | 4467 | 9.6 |

| Rigidity | 3954 | 8.5 |

| Bradykinesia | 3931 | 8.45 |

| Sleep problems | 3122 | 6.71 |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 1404 | 3.02 |

| Types of sleep complaint | Frequency (N (%)) |

|---|---|

| Poor sleep quality unspecified | 2703 (54.82%) |

| Sleep maintenance insomnia | 951 (19.29%) |

| Excessive sleepiness | 527 (10.68%) |

| RLS | 307 (6.22%) |

| RBD | 143 (2.9%) |

| Vivid dreams | 139 (2.81%) |

| Early morning awakening | 64 (1.29%) |

| Sleep onset insomnia | 49 (0.99%) |

| Sleepiness unspecified | 30 (0.6%) |

| Non-restful sleep | 10 (0.2%) |

| Parasomnia | 7 (0.14%) |

We next categorised PD patients based on considering sleep as the most or the fifth most bothersome symptom (the lowest ranking in the survey). The rate of insomnia experience and difficulty in getting to sleep or staying asleep during the night was significantly associated with sleep problems being endorsed as the most bothersome symptom, although there were not associations between the subjective ranking of sleep problems and insomnia diagnosis by a physician, sleep apnea (experience or diagnosis), RLS (experience or diagnosis) or vivid dream experience (Table 9). Patients with PD who mentioned sleep problems as their least bothersome symptom were more likely to have difficulty in staying awake during daily activities or to act out dreams.

| Variable | Sleep is the 5th most bothersome symptom | Sleep is the most bothersome symptom | χ2 | p | Phi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Having sleep problems |

60.6%, N = 1310 | 67.7%, N = 2715 | 7.96 | <0.0001 | 0.044 |

| Insomnia experience | 61.7%, N = 209 | 73%, N = 363 | 8.75 | 0.01 | 0.124 |

| Insomnia diagnosis from a physician | 56.6%, N = 129 | 55.1%, N = 265 | 0.07 | >0.05 | 0.014 |

| RLS experience | 34%, N = 209 | 32.5%, N = 363 | 0.12 | >0.05 | 0.015 |

| RLS diagnosis from a physician | 66.2%, N = 71 | 78%, N = 118 | 3.15 | >0.05 | 0.12 |

| Sleep apnea experience | 17.7%, N = 209 | 20.1%, N = 363 | 1.62 | >0.05 | 0.053 |

| Sleep apnea diagnosis from a physician | 86.5%, N = 37 | 81.1%, N = 74 | 0.5 | >0.05 | 0.068 |

| Difficulty staying awake during day | 55.3%, N = 1379 | 48.8%, N = 2669 | 15.25 | <0.0001 | 0.061 |

| Difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep | 93.5%, N = 1379 | 95.6%, N = 2669 | 8.06 | <0.01 | 0.045 |

| Vivid dream experience | 71.4%, N = 1379 | 69.1%, N = 2669 | 2.29 | >0.05 | 0.024 |

| Acting out dream | 58.7%, N = 1367 | 53.7%, N = 2612 | 9.32 | <0.01 | 0.048 |

We next undertook a logistic regression with sleep problems being endorsed as the most bothersome symptom as the dependent variable and sleep problems with large responding samples as the predictor variables. The presence of problems falling or staying asleep (aOR 0.18, 0.15–0.21), staying awake during the day (aOR 0.65, 0.60–0.70), experiencing vivid dreams (aOR0.71, 0.64–0.78), and acting out dreams (aOR 0.61, 0.57–0.68) were all associated with reduced odds of endorsing sleep as the most bothersome symptom (Table 10).

| Sleep problem | B | SE | Wald | Sig | Exp (B) | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep | −1.72 | 0.09 | 342.90 | <0.0001 | 0.18 | 0.15–0.21 |

| Difficulty staying awake | −0.43 | 0.04 | 118.90 | <0.0001 | 0.65 | 0.60–0.70 |

| Vivid dream experience | −0.34 | 0.05 | 54.65 | <0.0001 | 0.71 | 0.64–0.78 |

| Acting out dream | −0.47 | 0.07 | 115.76 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 0.57–0.68 |

We next examined functional and demographic measures which may vary between PD patients who endorsed that sleep problems are their most bothersome symptom (N = 3122), and those who endorsed that is the fifth most (“least”) bothersome symptom (N = 1753). Age and the age of diagnosis of PD did not vary between the groups (69.8 ± 0.18 years vs 69.4 ± 0.25 years for age respectively, p = 0.14; 60.5 ± 0.39 years vs 59.5 ± 0.57 years for age at diagnosis, p = 0.143; Figure 5a, b). A MANOVA for GDS, PDAQ and PDQ-8 scores between the two “sleep most/least bothersome” groups showed an effect (F(3,3250) = 34.8, p < 0.0001). The PDQ-8 scores were greater in participants who endorsed sleep was the fifth most bothersome symptom, indicating most PD-related QoL impairment in those reporting sleep as the “least” bothersome symptom (11.98 ± 0.13 for sleep most bothersome vs. 14.30 ± 0.17 for sleep “least” bothersome; p < 0.0001, d = 0.38; Figure 5c). Similarly, participants endorsing sleep as the “least” bothersome symptom scored higher on the geriatric depression scale (4.96 ± 0.08 for “most” vs. 5.87 ± 0.11 for “least”; p < 0.0001, d = 0.24; Figure 5d). PDAQ scores were significantly lower in those for whom sleep problems was the “least” bothersome symptom, indicating a greater level of cognitive impairment compared with those who endorsed sleep problems as their most bothersome symptom (53.53 ± 0.17 for “most” vs 51.64 ± 0.28 for “least”; p < 0.0001; d = 0.21 Figure 5e). Therefore, it appears that participants endorsing sleep as the most bothersome symptom had lower levels of quality-of-life impairment, depression and impairment of cognition-dependent independence than those who endorsed sleep problems as their fifth most bothersome symptom.

To further examine this issue, we compared the profile of participants who endorsed sleep problems as their most bothersome PD symptom compared with those who endorsed postural instability as their most bothersome symptom (the most commonly endorsed most bothersome symptom; N = 10,637). The mean age for PD patients whose sleep is the most bothersome symptom (69.38 ± 0.22) was significantly lower than for PD patients whose postural instability is the most bothersome symptom (71.47 ± 0.10; p < 0.0001); however, the age of first PD diagnosis did not differ (60.46 ± 0.048 for sleep most bothersome vs. 60.6 ± 0.28 for postural instability most bothersome; p = 0.81). Postural instability as the most bothersome symptom, compared with sleep as the most bothersome symptom, exerted an effect on PDQ-8, GDS, and PDAQ (MANOVA: F(3, 24,241) = 37.3, p < 0.0001). Postural instability as the most bothersome symptom was associated with greater depression (GDS scores of 5.41 ± 0.4 vs 4.69 ± 0.09, p < 0.0001, d = 0.27), more PD-related impairment of quality of life (PDQ-8 scores of 12.75 ± 0.15 vs 11.03 ± 0.15, p < 0.0001, d = 0.38), and more impairments of cognition-dependent independence (indicated by lower PDAQ scores: 51.85 ± 0.12 vs. 54.09 ± 0.19, p < 0.0001, d = 0.06; all Figure 6, Table 11.

| Domain | Main finding |

|---|---|

| Case–control comparison of sleep problems | PD patients endorse more subjective sleep problems, more sleep medication use, more insomnia and RLS experiences and diagnoses |

| Association of sex with sleep problems in PD | Males report more sleep problems, more RLS and insomnia experiences, less EDS and acting out dreams |

| Association of early onset PD with sleep problems | Early onset PD (before 50 years of age) associated with greater insomnia experience, greater EDS, greater vivid dreaming |

| Association of sleep problems in PD with depression, cognition and quality of life | PD patients with sleep problems or insomnia diagnosis report higher levels of depression and lower quality of life. Insomnia diagnosis was associated with greater cognitive impairment |

| Sleep problems and OFF periods | The presence of sleep problems was associated with greater occurrence of OFF periods and more OFF periods per day |

| Subjective ranking of sleep problems | ~7% of PD patients endorsed sleep problems as their most bothersome symptom. Patients endorsing sleep as the most bothersome symptom were younger than those who endorsed postural instability as their most bothersome symptom, and postural instability was associated with greater depression and cognitive impairment and poorer quality of life compared to sleep problems |

4 DISCUSSION

The current study explored various aspects of sleep and sleep problems in a large cohort of patients with PD. Our findings echo previous reports of high prevalence of sleep problems in PD, and build on these findings in describing the relationship of early-onset PD with greater levels of sleep problems, the association of sleep problems with cognition-dependent daily functioning and mood in PD, and the subjective ranking of how “bothersome” sleep symptoms are for PD patients. Previous reports of prevalence of sleep problems in PD range from 40% to 90% (Barone et al., 2009; Bollu & Sahota, 2017; Melka et al., 2019). As such, the subjective report rate of difficulty falling or staying asleep of 84% in PD in the current study is at the higher end of the previously reported range, and suggests a very high burden of sleep problems in PD. Daytime sleepiness is also endorsed as a frequent subjective complaint in PD (37%), and sleep medication use is reported in ~50% of PD patients.

Similar to previous studies, we show significant differences in the rates of sleep difficulties and daytime sleepiness between men and women with PD, and these sex differences depend on the sleep problem examined (Beydoun et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2019). Whilst it is not immediately clear why sleep problems in PD may vary according to sex, the prevalence of sleep disorders such as insomnia and sleep apnea are well described to vary with sex in the general population (Boer et al., 2023; Bublitz et al., 2022); such effects may result from interactions between biological, psychosocial, behavioural, cultural and medical factors, and these mechanisms may also influence the sex-dependency of sleep problems in PD. Further, both motor and non-motor symptoms of PD show sex differences and this may contribute to sex differences in sleep problems (de Souza Ferreira et al., 2022).

We report that patients with early-onset PD exhibit a higher prevalence of insomnia and vivid dream experience, difficulty staying awake during the day, and difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep at night at the time of reporting than patients whose disease was diagnosed later, and that such differences do not appear to be explained by the years-since-diagnosis. The results of previous studies on the association between early-onset PD and sleep are inconsistent; Liu et al., 2021 report that in 586 PD cases the Epworth sleepiness scale scores did not exhibit significant divergence between typical and early-onset PD patients and that poor sleep quality at night was only associated with typical-onset PD. Other studies have reported similar rates of sleep problems after parkinsonism onset in typical and early-onset PD patients (McCarter et al., 2023), and some have documented a lower incidence of RBD and insomnia in patients with early-onset PD in comparison with those with typical-onset PD (Baumann-Vogel et al., 2020; Mahale et al., 2021). Given that the aetiological and symptomatic profile of early-onset PD may differ from typical-onset PD, it is feasible that such differential pathophysiology and symptomatology might also manifest in terms of sleep problems, although more precise explanations for such effects are not afforded by the current data.

Previous studies have indicated associations between the poor sleep and mental health issues, including anxiety and depression in patients with PD (Kay et al., 2018; Koh et al., 2022; Rana et al., 2018; Xia et al., 2020). Consistent with previous reports, our results suggest that the presence of physician-diagnosed insomnia and/or self-reported difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep is associated with mood impairment, cognitive decline, and impaired quality of life (Hermann et al., 2020; Kay et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2014). It is not clear from the current data whether such effects are amplified in PD, as sleep problems are broadly reported to be associated with poorer mood, cognitive failures, and a lower quality of life in older adults (Nielson et al., 2023; Sella et al., 2023). Further, as the temporal relationships between these factors are not well understood (e.g. Raman et al., 2022), it is not clear whether sleep problems are risk factors, antecedents or a consequence of low mood and cognitive decline.

The presence of OFF periods, when symptoms re-emerge or worsen as a result of medication washout, is associated with impairment of the quality of life for people with PD (Thach et al., 2021). In our study, we identified an association between trouble falling or staying asleep and the occurrence of OFF episodes in PD. Limited previous evidence has hinted at an association between early morning OFF periods and nocturnal sleep problems (Han et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Our analysis found that OFF episodes were accompanied by daytime sleepiness which may impact the quality of life of patients and caregivers. Also, our results revealed an association between having sleep problems in falling or staying asleep with more hours spent in OFF periods and a greater number of OFF periods per day. There may be a bidirectional connection between sleep disturbances and the OFF episode as there is some evidence that sleep problems and sleepiness are influenced by dopaminergic medication, and fluctuation in motor symptoms has a correlation with daytime sleepiness (Höglund et al., 2021). However, there is no evidence available currently that interventions to improve sleep quality and/or duration in PD would result in decreased OFF periods.

Parkinson's disease is clinically highly heterogeneous (Bloem et al., 2021), and this is reflected in the range of responses to the “bothersomeness” of different motor and non-motor symptoms in the Fox Insight study. In the current cohort, postural instability emerged as the most prevalent bothersome symptom for PD patients, diverging from previous findings wherein tremor has been identified as the most troublesome symptom in numerous published studies (Hermanowicz et al., 2019; Mammen et al., 2023). When PD cases in this study were asked to rank their most bothersome symptom (1st–5th), sleep-related concerns were more frequently endorsed with decreasing rank within the five most bothersome symptoms; sleep was chosen as the top concern by almost 7% of participants, followed by a subsequent increase in frequency as the rank decreased to fifth (14% of participants characterising sleep as their fifth most bothersome symptom). So, it appears that whilst a significant number of patients identified other symptoms as more bothersome, they also experienced sleep problems as within the top five most impairing symptoms. Irrespective of the subjective ranking of sleep problems as the most or fifth most bothersome symptom, insomnia was identified as the most commonly endorsed sleep complaint; therefore, it does not appear that the subjective ranking of sleep problems is influenced by the nature of the sleep problem. Rather, the relative ranking of the sleep problems may reflect the severity of motor and non-sleep non-motor symptoms, rather than the severity of the sleep problems, as participants ranking sleep problems as the most bothersome had lower levels of Parkinson's disease related impairment of quality of life and cognition. The question of sleep problems as the most bothersome symptom in PD may warrant further investigation to probe whether this group represents a subgroup of clinical significance.

4.1 Strengths and weaknesses

The current study has a number of important strengths. The first is the size of the sample, which is large enough to represent the clinical heterogeneity of the population of patients with PD. Many of the previous studies of sleep in PD have been primary studies utilising smaller and/or more focussed samples (e.g. Höglund et al., 2021; Mahale et al., 2021). Therefore we believe that our study makes an important contribution to the literature and reinforces previous findings for the nature and over-representation of sleep problems in PD compared with matched healthy controls. Secondly, our study provides information on the potential clinical significance of sleep problems in PD, with such problems being associated with more symptoms of depression, more cognitive difficulties, lower quality of life, and more frequent/longer OFF periods. Thirdly, we believe that our report is the first describing the subjective ranking of sleep complaints within the symptom spectrum of PD, and as such provides significant new information.

Our study also has a number of weaknesses which should be considered in interpreting the results. The first is that the Fox Insight study items relevant for our analysis are based on subjective self-report, with many of the response items formulated in dichotomous yes/no formats. Such considerations are important in appreciating the nature of the analysis undertaken in the current study. Whilst some validated scales are used, the subsamples included for these items are considerably smaller than the overall study sample, and indeed the number of respondents varies considerably across the various questionnaires deployed in the Fox Insight study. Also related to the nature of the primary study, there was a bias in the propensity matched case–control sample leading to over-representation of females in this part of the analysis (arising from an imbalance in the full healthy control group); such an imbalance is notable for our findings of sex effects in the prevalence of some sleep issues. Secondly, we chose to undertake cross-sectional analysis for our study, although the Fox Insight study is a longitudinal one; we chose this approach partly as a response to the dichotomous nature of many of the responding items related to sleep examined which we believe would limit the meaningfulness of longitudinal analysis. As a result, we describe associations between the examined factors, and cannot make claims regarding directionality or causality for those relationships. Thirdly, as with analysis of large data sets, there was high statistical power which may allow for detection of statistically significant differences which may be of very small magnitude and of limited practical or clinical significance. As such, the nature of the detected differences should be interrogated above and beyond mere description of the presence of such differences. Fourthly, the number of sleep conditions enquired about was pre-specified as part of the broader Fox Insight study, and did not include some potentially relevant sleep conditions such as circadian rhythms sleep/wake disorders (Asadpoordezaki et al., 2023). Finally, as various medications used in the management of PD can impact on sleep, as can comorbid conditions that commonly present alongside PD, future work might usefully address specific subgroups of patients according to their clinical and/or pharmacological profiles.

4.2 Conclusion

A range of sleep problems are common in a large cohort of PD patients, and are associated with more adverse motor and non-motor features. As such, sleep represents an important and potentially modifiable feature to further explore in the management of PD to improve outcomes and quality of life.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ziba Asadpoordezaki: Investigation; writing – original draft; methodology; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; data curation. Beverley M. Henley: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; project administration; supervision. Andrew N. Coogan: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – original draft; methodology; validation; visualization; writing – review and editing; formal analysis; project administration; data curation; supervision; resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Fox Insight Study (FI) is funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research. We would like to thank the Parkinson's community for participating in this study to make this research possible.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors assert they have no conflict of interest with any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Michael J Fox Foundation. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from https://www.michaeljfox.org/fox-den with the permission of Michael J Fox Foundation.