Associations between sleep duration, insomnia, depression, anxiety and registry-based school grades: A longitudinal study among high-school students

Summary

This study explored the prospective associations between sleep patterns, mental health and registry-based school grades among older adolescents. In the spring of 2019, 1st year high-school students in Western Norway were invited to a survey assessing habitual sleep duration, insomnia, depression and anxiety. Sleep patterns, depression and anxiety were assessed using the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire, the Bergen Insomnia Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7. Students consenting to data linkage with the county school authorities were re-invited 2 years later. Registry-based grade point averages for each of the included school years were accessed through the school authorities. The final longitudinal sample included 1092 students (65.1% girls; initial mean age 16.4 years). Data were analysed using linear mixed models. Longer school night sleep duration and less severe symptoms of insomnia, depression and anxiety were all associated with higher grade point averages at baseline in crude analyses. Shorter school night sleep duration, as well as more severe symptoms of insomnia and depression at baseline, all predicted worse grade point averages at 2-year follow-up when controlled for baseline grade point averages. [Correction added on 30 December 2024, after first online publication: In the preceding sentence, the word “better” has been corrected to “worse”.] By contrast, anxiety symptomatology at baseline was unrelated to changes in grade point averages over time. The longitudinal associations between school night sleep duration and insomnia symptoms on grade point averages were significant also when adjusted for sex and baseline symptoms of depression and anxiety. These findings indicate that shorter school night sleep duration and more severe insomnia symptoms predict lower grade point averages development over time, irrespective of co-existing symptoms of depression and anxiety.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sleep is essential for adolescents' health and cognitive functioning, and may therefore play a significant role for their academic achievements (Lo et al., 2016). However, ample evidence across the globe shows that adolescents sleep less than recommended on school nights (Galland et al., 2018; Hirshkowitz et al., 2015), and a substantial proportion experience daytime sleepiness (Liu et al., 2019). In Norway, two large-scale studies have consistently shown that high-school students average less than 7 hr of sleep on school nights (Hysing et al., 2013; Saxvig et al., 2021). This is concerning, as studies indicate that adolescents aged 14–17 years need approximately 8–10 hr of sleep per night for adequate daytime functioning (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015; Short et al., 2018).

Insufficient sleep among adolescents is assumed to result from a variety of factors, including a transient delay in their circadian timing for sleep and slower accumulation of sleep pressure starting from early puberty, despite no change in the amount of sleep required for optimal daytime functioning (Carskadon, 2011; Hirshkowitz et al., 2015; Jenni et al., 2005). These biological changes contribute to a delay in the adolescents' endogenous circadian rhythm, which combined with early school start times and various psychosocial factors typical of adolescence (i.e. social media use) result in insufficient sleep on school nights (Boniel-Nissim et al., 2023; Crowley et al., 2018).

Furthermore, adolescence often marks the debut period of clinical sleep disorders, including insomnia (Johnson et al., 2006). Depending on the diagnostic criteria, insomnia may affect up to approximately a quarter of adolescents (Hysing et al., 2013), and tends to become chronic (Hysing et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2006). The main criteria include difficulties initiating and/or maintaining sleep, and/or early-morning awakening (EMA) despite adequate opportunities for sleep, combined with sleep-related worry and/or some form of daytime impairment. The symptoms need to be present for at least 3 days per week for a period of at least 3 months in order to comply with the diagnostic criteria for chronic insomnia (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014).

Poor sleep patterns among adolescents have been linked to cognitive deficits (Beebe et al., 2010), with potential implications for learning and school performance. For example, experimental studies have demonstrated poorer working memory after nights of restricted sleep (Lo et al., 2016), as well as reduced attention at school (Beebe et al., 2010). Disturbed sleep may also alter adolescents' school performance indirectly, for example through increased school absence or motivational deficits (Hysing et al., 2015; Hysing et al., 2016; Jurgelis et al., 2022). In line with this, studies have linked sleep problems among adolescents to poorer academic performance, more school absence, and higher dropout rates from school (Dewald et al., 2010; Hysing et al., 2015; Hysing et al., 2016; Hysing et al., 2023). For example, a meta-analysis by Dewald and colleagues based on cross-sectional studies found that daytime sleepiness was negatively, and sleep duration and -quality positively, associated with academic performance among children and adolescents (Dewald et al., 2010). Another recent meta-analysis based on US samples reported an overall positive association between sleep quality and school performance, but found no association between sleep duration and school performance (Musshafen et al., 2021). Inconsistency between studies could be due to methodological disparities (Dewald et al., 2010; Musshafen et al., 2021), or that the relationship between sleep and school performance may be affected by a variety of factors (Mehta, 2022).

While several studies have previously linked sleep problems to poorer academic performance, the cross-sectional designs used in most previous studies preclude inferences about directionality (Bacaro et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). Accordingly, it remains uncertain to which degree adolescents' sleep problems predate poorer grades, or vice versa. This issue is relevant to improve insight in how adolescents' sleep problems are linked to their academic performance over time, and longitudinal (i.e. prospective) studies may provide such insights (Zhang et al., 2022).

In spite of this, few studies have examined the prospective associations between adolescents' sleep patterns and school performance, according to a recent systematic review (Bacaro et al., 2023). The studies conducted to date have mostly failed to demonstrate a longitudinal association between sleep duration and school performance (Bacaro et al., 2023). For example, a US study based on 2259 middle-school adolescents concluded that although sleep duration was initially related to self-reported grades, changes in sleep duration were unrelated to changes in self-reported school performance over time (Fredriksen et al., 2004). Also, whereas preliminary evidence suggests that sleep disturbances predict poorer academic performance over time (Evers et al., 2020), only one previous study has explored whether insomnia specifically is prospectively related to adolescents' school performance (Zhang et al., 2022). This study found that insomnia at baseline predicted better self-evaluated skills in mathematics and overall academic performance, but not skills in English or Chinese, in a 1-year follow-up study from China.

However, most previous studies on the associations between sleep duration, insomnia and school performance are either based on subjectively reported school grades or on a limited number of school subjects (e.g. mathematics and language only; Bacaro et al., 2023; Takizawa & Kobayashi, 2022). The lack of objective school grades in previous research is unfortunate, as self-reported grades may be affected by, for example, self-protecting memory bias (Bahrick et al., 1996). Additionally, most previous studies have been conducted on younger adolescents, whereas less is known about the prospective associations between sleep at one point and later school grades among older adolescents. Finally, although poor sleep patterns among adolescents are highly correlated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (O'Callaghan et al., 2021; Orchard et al., 2020), there is a lack of studies taking the potential co-existence of depression and anxiety into account (Bacaro et al., 2023). There is therefore a need for studies addressing the trajectories between older adolescents' sleep patterns, mental health and school performance, based on registry-based data and across different school subjects.

As part of the Western Norway Adolescent Longitudinal Sleep Study (Saxvig et al., 2021), this study aimed to explore the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between sleep, depression, anxiety and registry-based school grades in a large sample of Norwegian high-school students. The main hypotheses were: (1) that longer sleep duration on school nights at baseline would predict better academic development from baseline to follow-up 2 years later; and (2) that students who screened positive for the insomnia diagnosis at baseline, or who reported higher insomnia symptom severity at baseline, would have poorer academic development over time. We further hypothesized that levels of depression and anxiety would be positively related to the students' grade point averages (GPAs) cross-sectionally at baseline (hypothesis 3). Finally, we hypothesized that both depression, anxiety and sleep patterns (sleep duration and insomnia, investigated separately) would be significant predictors of GPA development in fully adjusted analyses (hypothesis 4).

2 METHODS

In the period April–June 2019, all 1st year high-school students in the counties Hordaland and Rogaland in Western Norway were invited to participate in a web-based survey assessing habitual sleep habits, insomnia, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Students in Hordaland were invited through the electronic school-based platform “itslearning”, whereas students in Rogaland were invited through SMS or e-mail. School authorities in both counties were encouraged to inform the involved school administrations about the survey, and to allocate one school hour to complete the survey. Additionally, students were asked to provide permission for the research group to collect their registry-based school grades from the county administrations. Students who consented to registry-based grade linkage were re-invited to complete a similar version of the survey, comprising the same questions related to sleep and mental health, in the spring of 2021. To increase the incentive to respond, responders of the 2-year follow-up survey were offered to be included in a lottery with the chance of winning one of a total of 100 gift cards of 500, - NOK (corresponding to approximately 50, - USDs) or one of five of the latest Apple iPhone Pro (version 12).

3 SAMPLING PROCEDURE

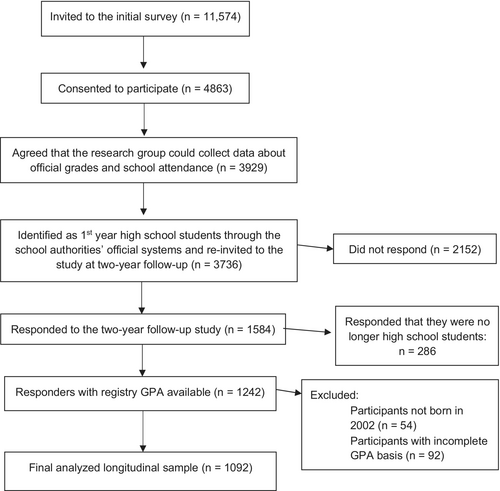

For complete flow over participants, see Figure 1. The estimated total number of 1st grade high-school students in the two counties was, according to the invited schools, 11,574. From these, 4863 students consented to participate in the initial wave of the study in 2019, of which 3929 students agreed that the researchers could collect data about grades and school attendance from their respective school authorities. Only students who responded to the first wave of the study and consented to collection of official school grades were re-invited to the study in 2021.

In total, 3736 participants who responded to the baseline survey and were identified as 1st year high-school students through the school authorities' official systems at baseline were re-invited to the 2-year follow-up survey. Among these, 1584 responded, yielding a response rate of 42.4%. From these, 1276 responded that they were still high-school students. Of these, registry-based GPAs for the follow-up school year were available for 1242 by the end of the school year (539 from Hordaland and 703 from Rogaland). Data for 54 of these 1242 students not born in 2002 were excluded from further analyses to eliminate potential age-related effects. Four additional participants were excluded from further analyses due to clearly invalid answers (negative sleep duration either at baseline or follow-up). Students with data registered as either “passed” (n, follow-up = 1065), “competed, but not passed” (n, follow-up = 9), or “not completed” (n, follow-up = 18) were included in the final analyses. By contrast, data from 92 students were excluded from further analyses due to incomplete grade records. This included students who had dropped out for unknown reason, were studying part-time, or had no grades registered, as these groups often had fewer grades available for analyses. Thus, the final sample comprised 1092 participants.

4 ETHICS

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK sør-øst 2019/110) and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD number 758174). Furthermore, and in line with Norwegian regulations, invited participants were required to confirm that they were at least 16 years old and to give informed consent to participate in the study before receiving full access to the survey.

5 INSTRUMENTS

5.1 Demographics

The surveys included items related to demographics, including birth date, sex (“boy”/“girl”), and maternal and paternal educational levels (primary/secondary school, high-school, college/university < 4 years, college/university ≥ 4 years, and “I do not know”).

5.2 Sleep pattern assessments

Sleep patterns during the past 4 weeks were assessed using a Norwegian adaptation of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ; Roenneberg et al., 2003) for children and adolescents. The scale assesses self-reported sleep on school and free days, respectively, based on the past 4 weeks. The scale targets the following sleep items: bedtime (BT); time of preparing to sleep (SPrep); sleep latency (SLat); and sleep end (SEnd). The survey further included one item assessing wake after sleep onset (WASO; referring to the total time spent awake in-between the sleep period) on school and free days separately.

All response options were presented through drop-down menus. Clock time items (BT, SPrep and SEnd) were presented as 15-min-interval scales, and items addressing duration (SLat and WASO) were presented on 5-min-interval scales. BT and SPrep were presented in the range between "20:00 hours or earlier" and "08:00 hours or later"; SEnd between "05:00 hours or earlier" and "17:00 hours or later"; whereas the options for SLat and WASO ranged from 0 min to “5 hours or more”. Based on these items, sleep duration was calculated as the discrepancy between the participants' sleep onset time (SPrep + SLat) and SEnd, minus WASO.

5.3 Insomnia assessments

Insomnia was assessed by the Bergen Insomnia Scale (BIS; Pallesen et al., 2008). BIS is a six-item self-report questionnaire assessing DSM-5 criteria for insomnia along an eight-point scale, ranging from 0 to 7 days per week during the past 3 months. BIS assesses how many days per week the respondent has experienced each of the following symptoms of insomnia, on average: prolonged sleep-onset latency (SOL; > 30 min); WASO (> 30 min); EMA (> 30 min before preferred wake-up time); non-restorative sleep; sleep-related dissatisfaction/worry; and/or impaired daytime functioning. To screen positive for the insomnia diagnosis, the BIS requires that at least one of the nocturnal symptoms of insomnia (SOL, WASO or EMA), combined with either sleep-related dissatisfaction and/or impaired daytime functioning, must have been present for at least 3 days a week over the past 3 months. Also, a composite score is obtained by summarizing the value of each item, resulting in possible scores ranging from 0 to 42, of which a higher total score indicates more severe insomnia symptoms. BIS discriminates well between clinical and non-clinical populations, and has good psychometric properties (Pallesen et al., 2008). In the present sample, Cronbach's alpha was 0.77 at baseline and 0.79 at follow-up.

5.4 Depression and anxiety symptoms

A Norwegian adaptation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Spitzer et al., 1999) was used to assess symptoms of depression. The PHQ-9 is a validated self-report questionnaire assessing nine core symptoms of depression and is commonly used in clinical and research settings, with good psychometric properties (Burdzovic Andreas & Brunborg, 2017; Kroenke et al., 2001; Levis et al., 2019). The scale asks how many days each depressive symptom has been present during the past 2 weeks along a four-point scale, with the following response options: “Not at all” = 0; “Several days” = 1”; “More than half the days” = 2; and “Nearly every day” = 3. A total score is calculated by summarizing the value of each item, resulting in an overall score of 0–27, of which a higher score indicates a higher level of depression. In the current study, a cut-off score of 10 or higher was used to define possible clinical depression. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.87 at baseline and 0.89 at follow-up.

The students' anxiety levels were assessed using a Norwegian version of the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006). GAD-7 is a seven-item questionnaire assessing seven core symptoms of anxiety. The scale asks how many days each symptom has been present during the past 2 weeks along a four-point scale. The response options are “Not at all” (= 0); “Several days” (= 1)”; “More than half the days” (= 2); and “Nearly every day” (= 3). A composite score is obtained by summarizing the score of each item, resulting in a possible score ranging from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates higher levels of anxiety. The scale may also be used to indicate a diagnosis of anxiety, of which a score of 8 or higher is recommended as clinical cut-off (Plummer et al., 2016). In this study, the cut-off criterion for possible anxiety was therefore 8 or higher. The scale shows good psychometric properties, and is widely used in both research and clinical settings (Spitzer et al., 2006). Cronbach's alphas were 0.89 at baseline and 0.91 at follow-up.

5.5 School grades

Information regarding participants' final school grades for each school year was collected through the students' respective school authorities. In Norway, high-school students achieve grades ranging from 1 (fail) to 6 (excellent), or 0 (incomplete grade basis, e.g. due to excessive school absence). The average score of each students' grades is thereafter multiplied by 10, resulting in a possible total grade ranging from 0 to 60. In the present study, the GPAs (0–60) of each of the two included school years (baseline and 2-year follow up) were used separately.

6 STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Paired sample's t-tests were conducted to compare the students' sleep duration and insomnia symptom levels (total score) at baseline (year 2019) versus the 2-year follow-up (2021). Also, McNemar chi-square tests were conducted to assess whether the rates of participants fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for insomnia, based on the BIS, differed from baseline to follow-up. McNemar test was also used to assess whether the rates of participants screening above cut-off for levels of depression and anxiety changed from baseline to follow-up. Furthermore, an independent sample t-test was conducted to investigate whether there were sex differences in the students' GPAs at baseline. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted at baseline to investigate whether there were differences in baseline grades among students reporting less than 7 hr, 7–8 hr, or 8 h of sleep or more. Finally, independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests for independence were conducted to investigate whether there were differences in terms of age, sex, GPA and the outcome variables among responders and non-responders of the follow-up survey. All descriptive statistics were conducted using IBM SPSS, version 29.

To control for clustering of students within classes and classes within schools, all main analyses were conducted using linear mixed effects models in STATA, version 18.0. In cases where intraclass correlations were larger within classes than schools, both schools and classes within schools were included as random factors. P-Values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

6.1 Predictors and outcome variables

The outcome variable was GPA at follow-up in the longitudinal analyses, and GPA at baseline in the cross-sectional analyses. The included sleep parameter predictors were school night sleep duration (assessed in minutes) during the past 4 weeks, insomnia symptom severity (based on the total score on the BIS), and whether the participants screened positive for the insomnia diagnosis based on the diagnostic criteria of the BIS. The mental health predictors were continuous levels of depression, continuous levels of anxiety, scores above the cut-off range for depression, and scores above the cut-off range for anxiety. Also, the participants' reported sex at baseline was included as a covariate in fully adjusted analyses.

In crude longitudinal analyses investigating the associations between sleep patterns and GPA development, the main outcome variable was therefore GPA at follow-up, whereas the main predictors were GPA at baseline combined with each of the three sleep parameters of interest, investigated separately. Likewise, in the crude analyses investigating the longitudinal associations between mental health and GPA, the outcome variable was GPA at follow-up, whereas the predictors were baseline GPA and the mental health variables of interest at baseline.

Furthermore, crude analyses were conducted to examine the baseline associations between GPA and the above sleep and mental health parameters. For both the cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, all three sleep variables' associations with GPA were also investigated in fully adjusted analyses with continuous levels of depression and anxiety, as well as the participants' reported sex at baseline, added as predictors.

Potential multicollinearity was assessed by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) in regression analyses prior to the mixed analyses adjusted for school and class. None of these analyses indicated problematic multicollinearity, as indicated by VIF values < 5 and tolerance values > 0.2 (Kutner et al., 2004).-

7 RESULTS

The final analytic sample included 1092 participants (65.1% females; mean age = 16.4 years at baseline). For descriptive statistics, please see Table 1. Responders of the follow-up survey were younger, more often female, slept 13 min longer, and had higher GPA at baseline, relative to participants who only responded to the baseline survey (all p-values < 0.001; for more details, see Table 2). Students who slept less than 7 hr at baseline had significantly lower GPA (M = 44.54, SD = 7.2) relative to students who slept 7–8 hr (M = 46.53, SD = 6.4) or 8 hr or more (M = 46.75, SD = 6.4).

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Male | 381 (34.9%) |

| Female | 711 (65.1%) |

| Age, N (%) | |

| 16 years | 689 (63.1%) |

| 17 years | 403 (36.9%) |

| Sleep duration, grouped (%) | |

| Sleep duration < 7 hr | 492 (45.3%) |

| Sleep duration 7–8 hr | 449 (41.3%) |

| Sleep duration > 8 hr | 146 (13.4%) |

| GPA, M (SD) | |

| Both sexes | 45.66 (6.82) |

| Girls | 46.08 (6.74) |

| Boys | 44.86 (6.91) |

| Maternal educational level, N (%) | |

| Primary/secondary school | 39 (3.6%) |

| High-school | 177 (16.2%) |

| College/university < 4 years | 243 (22.3%) |

| College/university ≥ 4 years | 498 (45.6%) |

| Do not know | 135 (12.4%) |

| Paternal educational level, N (%) | |

| Primary/secondary school | 44 (4.0%) |

| High-school | 248 (22.7%) |

| College/university < 4 years | 198 (18.1%) |

| College/university ≥ 4 years | 422 (38.6%) |

| Do not know | 180 (16.5%) |

- GPA, grade point average; M, means; N, number of students; SD, standard deviations.

| Non-responders | Responders | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 16.8 (1.7) | 16.5 (1.1) | <0.001a |

| Females (%) | 49.2% | 60.2% | <0.001b |

| Baseline GPA, M (SD) | 41.4 (8.2) | 44.5 (7.7) | <0.001a |

| Total sleep time, M (SD) | 6:27 (1:52) | 6:40 (1:36) | <0.001a |

| BIS, total score, M (SD) | 12.4 (8.6) | 12.3 (8.1) | 0.750a |

| PHQ-9, M (SD) | 7.4 (5.8) | 7.6 (5.6) | 0.185a |

| GAD-7, M (SD) | 5.7 (4.9) | 5.9 (4.8) | 0.184a |

| Insomnia positive1 (%) | 37.1% | 33.9% | 0.049b |

| Depression positive2 (%) | 28.7% | 29.1% | 0.824b |

| Anxiety positive3 (%) | 27.5% | 28.4% | 0.593b |

- aBased on independent samples t-tests, two-tailed.

- bBased on chi-square test for independence (with continuity correction).

- BIS, Bergen Insomnia Scale; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GPA, grade point average; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

- 1 Based on the cut-off criteria on BIS.

- 2 Based on the cut-off score of ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9.

- 3 Based on the cut-off score of ≥ 8 on the GAD-7.

As shown in Table 3, the average sleep duration in the final analytic sample was 6 hr and 53 min at baseline, and remained stable at 2-year follow-up (p = 0.414). By contrast, the level of insomnia symptoms increased during the 2-year period, from a total BIS score of 11.9 at baseline to 12.8 at follow-up (p < 0.001). In terms of the insomnia diagnosis, approximately a third of the sample (32.4%) met the diagnostic criteria for chronic insomnia at baseline, and the rate remained relatively stable at the 2-year follow-up (p = 0.096). Both symptom levels of anxiety and depression and the rate of students screening positive for the disorders increased from baseline to follow-up (all p-values < 0.001; Table 3). The mean GPA was 45.7 at baseline and increased significantly to 46.5 at follow-up (p < 0.001). Girls had a slightly higher GPA than boys, both at baseline (p = 0.005) and follow-up (p = 0.025; Table 3).

| Baseline (M, SD) | Follow-up (M, SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School night sleep duration (hr:min) | 6:53 (± 76 min) | 6:55 (± 72 min) | 0.414a |

| BIS, total score | 11.9 (7.6) | 12.8 (8.1) | < 0.001a |

| PHQ-9, total score | 7.3 (5.3) | 8.7 (5.9) | < 0.001a |

| GAD-7, total score | 5.9 (4.7) | 6.5 (5.1) | < 0.001a |

| Insomnia positive1 (%) | 32.4% | 35.4% | 0.096b |

| Depression positive2 (%) | 27.4% | 36.9% | < 0.001b |

| Anxiety positive3 (%) | 27.8% | 33.4% | < 0.001b |

| GPA | 45.66 (6.82) | 46.48 (8.15) | < 0.001a |

- aBased on paired sample's t-tests, two-tailed.

- bBased on McNemar's test.

- BIS, Bergen Insomnia Scale; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GPA, grade point average; hr, hours; M, mean; min, minutes; SD, standard deviation.

- 1 Based on the cut-off criteria on BIS.

- 2 Based on the cut-off score of ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9.

- 3 Based on the cut-off score of ≥ 8 on the GAD-7.

8 BASELINE ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SLEEP, DEPRESSION, ANXIETY AND GPA

For all baseline and follow-up analyses, intraclass correlation matrices revealed that classes counted for more unexplained variance than the students' schools. Accordingly, all analyses were adjusted for both the students' school and class by including these as random factors.

At baseline, longer sleep duration on weekdays was related to higher GPA (Table 4). Furthermore, insomnia symptom severity was inversely related to GPA. Likewise, students qualifying for the insomnia diagnosis at baseline had lower GPA, relative to students without the diagnosis (Table 4).

| B | SE (B) | p-value | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline predictors of GPA | ||||

| Sleep patterns | ||||

| School night sleep duration (min; n = 1087) | 0.017 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | [0.012, 0.022] |

| BIS, continuously (n = 1054) | −0.132 | 0.026 | < 0.001 | [−0.183, −0.081] |

| BIS, diagnosis (reference: no insomnia; n = 1087) | −2.01 | 0.418 | < 0.001 | [−2.830, −1.191] |

| Depression (n = 1040) | ||||

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.155 | 0.038 | < 0.001 | [−0.229, −0.081] |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | −1.08 | 0.446 | 0.015 | [−1.959, −0.209] |

| Anxiety (n = 1037) | ||||

| GAD-7, continuously | −0.094 | 0.042 | 0.027 | [−0.177, −0.010] |

| GAD-7 ≥ 8 | −1.02 | 0.441 | 0.021 | [−1.881, −0.152] |

| Longitudinal predictors of GPA at follow-up, controlled for baseline GPA | ||||

| Sleep patterns | ||||

| School night sleep duration (min; n = 1087) | 0.009 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | [0.005, 0.013] |

| BIS, continuously (n = 1054) | −0.062 | 0.022 | 0.004 | [−0.105, −0.020] |

| BIS, diagnosis (reference: no insomnia; n = 1054) | −0.970 | 0.346 | 0.005 | [−1.649, −0.292] |

| Depression (n = 1040) | ||||

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.062 | 0.030 | 0.041 | [−0.121, −0.002] |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 (reference: no depression) | −0.822 | 0.353 | 0.020 | [−1.514, −0.130] |

| Anxiety (n = 1037) | ||||

| GAD-7, continuously | −0.016 | 0.034 | 0.643 | [−0.082, 0.050] |

| GAD-7 ≥ 8 | −0.343 | 0.349 | 0.325 | [−1.027, 0.340] |

- aBased on the diagnostic criteria of the BIS.

- B, coefficients; BIS, Bergen Insomnia Scale; CI, confidence interval; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GPA, grade point average for each of the included school years; SE (B), standard error of B.

In terms of the associations between mental health and GPA, students who scored above the cut-off for depression and anxiety had lower GPA relative to students who screened negative for the disorders. Similarly, higher symptom severity of both depression and anxiety was associated with lower GPA (Table 4).

In fully adjusted analyses, the cross-sectional association between school night sleep duration and GPA was attenuated, but remained significant, when controlled for sex and continuous levels of depression and anxiety at baseline (Table 5). Similarly, the associations between insomnia symptoms and GPA, and between the insomnia diagnosis and GPA, remained significant when controlling for sex and baseline levels of depression and anxiety (Table 5). In all the fully adjusted analyses, male sex and higher depression symptom severity were related to lower GPA, whereas anxiety was a non-significant contributor of the associations (Table 5).

| B | SE (B) | p-value | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPA predicted by school night sleep duration, depression, anxiety and sex | ||||

| School night sleep duration (min) | 0.015 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | [0.009, 0.020] |

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.15 | 0.057 | 0.009 | [−0.262, −0.038] |

| GAD-7, continuously | 0.045 | 0.064 | 0.479 | [−0.080, 0.171] |

| Sex (reference: females) | −1.604 | 0.435 | < 0.001 | [−2.455, −0.752] |

| GPA predicted by insomnia symptoms, depression, anxiety and sex | ||||

| BIS, continuously | −0.105 | 0.033 | 0.001 | [−0.170, −0.041] |

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.130 | 0.062 | 0.037 | [−0.252, −0.008] |

| GAD-7, continuously | 0.045 | 0.065 | 0.489 | [−0.082, 0.172] |

| Sex (reference: females) | −1.734 | 0.438 | < 0.001 | [−2.592, −0.876] |

| GPA predicted by insomnia by diagnosis, depression, anxiety and sex | ||||

| Insomnia diagnosisa (reference: no insomnia) | −1.468 | 0.465 | 0.002 | [−2.379, −0.556] |

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.152 | 0.060 | 0.011 | [−0.269, −0.035] |

| GAD-7, continuously | 0.029 | 0.065 | 0.652 | [−0.098, 156] |

| Sex (reference: females) | −1.676 | 0.438 | < 0.001 | [−2.53, −0.818] |

- aBased on the diagnostic criteria of the BIS.

- B, coefficients; BIS, Bergen Insomnia Scale; CI, confidence interval; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GPA, grade point average for each of the included school years; SE (B), standard error of B.

9 LONGITUDINAL ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SLEEP, DEPRESSION, ANXIETY AND GPA

Longitudinally, longer school night sleep duration at baseline predicted higher GPA at follow-up after adjusting for baseline GPA (Table 4), suggesting that students with more sleep on school nights had greater academic development over time. Furthermore, higher insomnia symptom severity at baseline was related to lower GPA at follow-up after controlling for GPA at baseline. Similarly, students who screened positive for the insomnia diagnosis at baseline had poorer GPA at follow-up when adjusted for baseline GPA, relative to students who did not qualify for the disorder (Table 4).

In terms of the longitudinal associations between mental health symptoms and GPA, both higher depression symptom severity and symptoms above the cut-off for depression predicted lower GPA at follow-up when adjusted for baseline GPA (Table 4). However, neither anxiety symptom severity nor anxiety symptoms above the cut-off were related to the students' GPA at follow-up when adjusting for baseline GPA (Table 4).

In fully adjusted analyses, the longitudinal association between school night sleep duration at baseline and GPA development was slightly attenuated, but remained significant, when controlling for sex as well as symptoms of depression and anxiety at baseline (Table 6). Similarly, both higher insomnia symptom severity and insomnia symptoms severe enough to qualify for insomnia diagnosis at baseline predicted lower GPA at follow-up, also when adjusted for sex and symptoms of depression and anxiety at baseline. By contrast, neither sex nor symptoms of anxiety or depression at baseline were significant predictors of GPA at follow-up in the fully adjusted analyses (Table 6).

| B | SE (B) | p-value | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration at baseline predicting GPA at follow-up, controlled for GPA, sex, depression and anxiety at baseline | ||||

| School night sleep duration (min) | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 | [0.003, 0.012] |

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.088 | 0.046 | 0.056 | [−0.178, 0.002] |

| GAD-7, continuously | 0.078 | 0.051 | 0.131 | [−0.023, 0.179] |

| GPA, wave 1 | 0.843 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | [0.794, 0.893] |

| Sex (reference: females) | −0.348 | 0.351 | 0.322 | [−1.037, 0.341] |

| Insomnia symptoms at baseline predicting GPA at follow-up, controlled for GPA, sex, depression and anxiety at baseline | ||||

| BIS, continuously | −0.065 | 0.026 | 0.013 | [−0.116, −0.013] |

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.068 | 0.050 | 0.174 | [−0.165, 0.030] |

| GAD-7, continuously | 0.079 | 0.052 | 0.126 | [−0.022, 0.180] |

| GPA, wave 1 | 0.851 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | [0.801, 0.900] |

| Sex (reference: females) | −0.411 | 0.352 | 0.244 | [1.101, 0.280] |

| Insomnia diagnosis at baseline predicting GPA at follow-up, controlled for GPA, sex, depression and anxiety at baseline | ||||

| Insomnia diagnosisa (reference: no insomnia) | −0.910 | 0.370 | 0.014 | [−1.636, −0.184] |

| PHQ-9, continuously | −0.082 | 0.048 | 0.087 | [−0.175, 0.012] |

| GAD-7, continuously | 0.069 | 0.051 | 0.178 | [−0.032, 0.170] |

| GPA, wave 1 | 0.850 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | [0.801, 0.900] |

| Sex (reference: females) | −0.376 | 0.352 | 0.286 | [1.066, 0.314] |

- aBased on the diagnostic criteria of the BIS.

- B, coefficients; BIS, Bergen Insomnia Scale; CI, confidence interval; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GPA, grade point average for each of the included school years; SE (B), standard error of B.

10 DISCUSSION

This study explored the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between sleep duration, insomnia, depression and anxiety symptoms, and school performance among Norwegian high-school students, based on registry-based GPA. At baseline, school night sleep duration was positively, whereas symptoms of insomnia, depression and anxiety were inversely, related to GPA. Similarly, students who screened positive for the insomnia diagnosis, or who scored above the cut-off criteria for depression or anxiety, had lower GPA than students screening negative for these diagnoses. Longitudinally, we found that longer sleep duration, less severe insomnia symptoms, and screening negative for the insomnia diagnosis at baseline all predicted better GPA at 2-year follow-up when controlling for GPA at baseline. In terms of mental health, we found that higher symptom levels of depression, as well as depression symptoms above cut-off, both predicted lower GPA development over time. By contrast, no longitudinal association was found between anxiety symptomatology and GPA development. In fully adjusted analyses, the longitudinal relationship between sleep duration and GPA was only slightly attenuated when adjusting for sex and symptom levels of depression and anxiety at baseline. Similarly, the longitudinal associations between insomnia and GPA development remained significant when controlling for sex and baseline levels of depression and anxiety. Neither sex nor baseline levels of depression or anxiety were related to GPA development in the fully adjusted analyses.

The longitudinal relationship between school night sleep duration and GPA supported hypothesis 1, stating that longer sleep duration at baseline would predict better academic performance over time. Combined with the cross-sectional finding that longer sleep duration was associated with better GPA at baseline, the result suggests that students with longer sleep duration have academic advantages over their poorer sleeping classmates, and that these advantages cumulate over time. Results of the present study mostly contrast previous studies suggesting that the evidence of a longitudinal association between sleep and school performance among adolescents is unclear (Bacaro et al., 2023). Variable findings across studies could be due to methodological differences. For example, most previous studies have, as previously discussed, used younger cohorts or been based on self-reported school grades, and often in a few school subjects. Also, and reflecting the fact that the present study relied on average grades across all school subjects, the current study investigated GPA at decimal levels, which may have allowed for detection of smaller differences. By contrast, some previous studies have rather asked students about their typical grade level but not included scores between grades (e.g., Fredriksen et al., 2004). Nevertheless, variable findings between the present and previous studies, and the relative lack of studies on the topic to date, suggest that more research is needed.

Furthermore, the findings that both higher insomnia symptom severity and qualifying for the insomnia diagnosis at baseline predicted lower GPA development supported hypothesis 2. These findings suggest that adolescents with higher insomnia severity burden have poorer academic development over time, compared with adolescents with less severe insomnia symptoms. The findings are in line with the study by Zhang et al. (2022) showing that insomnia was longitudinally related with poorer self-reported mathematics skills among adolescents 1 year later. The finding also corresponds with a meta-analysis linking insomnia to impairment in several cognitive domains (Wardle-Pinkston et al., 2019), as cognitive impairments may inhibit learning.

Although both depression and anxiety were related to poorer school performance at baseline when investigated independently of the adolescents' sleep patterns, only depressive symptomatology was related to GPA development over time in crude longitudinal analyses. Hypothesis 3, stating that symptoms of depression and anxiety would predict lower GPA development, was therefore only partially supported. Importantly, whereas all the investigated sleep variables were significant predictors of GPA development in fully adjusted analyses, neither depression nor anxiety symptoms remained significant predictors of GPA in these fully adjusted analyses controlled for sleep, depression and anxiety levels, and sex (hypothesis 4). This indicates that short sleep duration and insomnia predict worse academic outcomes over time, independent of co-existing anxiety and depressive symptoms.

10.1 Implications

Most previous studies on the association between adolescents' sleep patterns and school performance have been cross-sectionally based, which precludes inferences about direction and causation. The present study showed that shorter sleep duration, screening positive for insomnia, and more severe insomnia symptoms were all related with poorer GPA at baseline, and that these unfavourable associations between sleep and GPA increased over time. It should be noted that the study's observational design permits causal conclusions. Yet, the result that poor sleep patterns precede poorer academic performance indicates that sleep patterns may have a causal role for adolescents' academic results. While it should be noted that the associations between sleep patterns and changes in GPA were small, they may still be relevant with regard to future college and university admissions, as the students' admission points involve GPA at decimal levels. Several mechanisms potentially underlying the observed associations have been identified in previous studies. For example, poor sleep and insomnia have been related to cognitive impairments and reduced motivation (Lo et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019), which may have diminished the students' learning outcomes. Others have noted that the associations between adolescents' sleep patterns probably are complex and may involve a variety of factors, including the adolescents' social environment (Bacaro et al., 2023; Takizawa & Kobayashi, 2022).

Results of the current study indicate that intervening on adolescents' sleep problems may be central to optimize their school performance. In line with this, some preliminary evidence suggests that later school start times to allow adolescents to sleep in accordance with their intrinsic sleep timing are related with better school performance, although a recent review concluded that the overall impact of later school start times on adolescents’ school performance is not yet supported across studies (Biller et al., 2022). In terms of the observed associations between school performance on insomnia, however, the results indicate that insomnia-specific treatment may be necessary, as insomnia is a relatively stable condition and assumably maintained by insomnia-specific components, such as ruminative thoughts about one's experienced sleep problem (Harvey, 2002). However, it should be noted that the lack of tools to differentiate between insomnia and circadian or behavioural causes of insufficient sleep in the current sample means that one cannot be certain whether the insomnia rate represented true insomnia.

10.2 Strengths and limitations

The current study is among a few to have investigated the longitudinal associations between sleep patterns and school performance based on objective school grades from multiple school subjects, and among older adolescents. A major strength is the use of official school grades, which eliminated the risk of memory/reporting bias that could otherwise arise from self-report. Another strength was that all school courses were included, as opposed to many previous studies that have reported grades from a narrow scope of subjects. Furthermore, the estimation of sleep duration was based on multiple sleep parameters, which may have resulted in more precise estimates than studies relying on sleep estimates based on single sleep items only, typical of many previous studies (Bacaro et al., 2023; Dewald et al., 2010). Finally, the relatively large sample size of 1092 participants enhances the study's external validity.

The study also had several limitations. First, although participants' sleep duration assessments relied on several sleep parameters from the MCTQ, the estimates were still subjectively based and may consequently have been subject to biases. Also, the diagnosis of insomnia, depression and anxiety all relied on screening questionnaires rather than thorough clinical assessments. However, although clinical interviews would yield more accurate diagnostics, the use of screening tools allowed for a far larger sample size to be included than would be practically feasible if objective and/or clinical assessments were used instead, which we believe largely justify the assessments in the present study. Also, all screening relied on reliable and valid instruments.

As the invited schools were encouraged to devote one school hour to complete the survey at baseline, the study may have been somewhat underrepresented by students with clinical insomnia, depression or anxiety, as these disorders are all associated with more school absence (Askeland et al., 2020; Finning et al., 2019; Hysing et al., 2015). Similarly, as the sample was limited to students with adequate school grade basis, it may have been overrepresented by students with adequate daytime functioning. Furthermore, no adjustments were made to differentiate between demanding and less demanding school courses in the students' GPA. In Norway, high-school students may receive up to four additional credits for courses assumed to be more demanding (e.g. higher-level courses within mathematics), which are added to the students' overall final 3-year GPA. As credit information was not available from the county administrations, the GPA of students taking more demanding courses may thus have been somewhat underestimated.

Another potential weakness is that the follow-up data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, the findings may have been affected by temporary COVID restrictions, such as remote teaching. The use of mixed models including students' school and class as random factors at baseline may have, at least to some extent, adjusted for potential differences in restrictions across schools, as pandemic restrictions in the final year of the study differed across schools. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that results would differ if the data were not collected during the pandemic.

11 CONCLUSION

The present study showed that longer school night sleep duration and lower symptom levels of insomnia were related to better academic development among Norwegian high-school students. The associations between students’ sleep patterns and academic development were independent of sex and the students’ levels of depression and anxiety at baseline. The results imply that effectively targeting adolescents’ sleep may be pivotal in interventions seeking to optimize adolescents’ school performance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Linn Nyjordet Evanger: Writing – original draft; methodology; visualization; formal analysis; investigation. Ståle Pallesen: Conceptualization; investigation; funding acquisition; methodology; writing – review and editing; supervision; project administration. Ingvild West Saxvig: Conceptualization; investigation; funding acquisition; methodology; writing – review and editing; project administration; supervision. Mari Hysing: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – review and editing. Børge Sivertsen: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – review and editing. Stein Atle Lie: Formal analysis; supervision. Michael Gradisar: Writing – review and editing; conceptualization; investigation. Bjørn Bjorvatn: Conceptualization; investigation; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; methodology; supervision; project administration; formal analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors want to thank all the students who participated in the study, as well as Rogaland and Hordaland County administrations.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Rogaland County Municipality.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr Gradisar consults for Sleep Cycle AB and is the CEO of Wink Sleep Pty Ltd.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.