Chlormethiazole as a hypnotic in elderly patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Summary

The study objective was to estimate the efficacy and safety of chlormethiazole in older adults experiencing insomnia (sleep disorder). We therefore systematically searched Medline, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Ovid, ZB MED and PMC through December 2021 for randomized–controlled trials including patients > 60 years old with insomnia treated with chlormethiazole. Standardized mean differences or odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the main outcome parameters: sleep duration, onset of sleep, quality of sleep, adverse events or drop-out rates compared with placebo and other drugs. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool. Eight randomized–controlled trials with 424 patients were included. Chlormethiazole significantly increased the duration of sleep when compared with placebo (standardized mean difference = 0.61; 95% confidence interval = 0.11–1.11; p = 0.02). More patients receiving chlormethiazole had adequate quality of sleep than those receiving other drugs (odds ratio = 1.44; 95% confidence interval = 1.04–1.98; p = 0.03). No differences were found regarding the onset of sleep (standardized mean difference = 1.07; 95% confidence interval = 0.79–1.46; p = 0.65). Drop-out rates were significantly lower under chlormethiazole treatment when compared with other drugs (odds ratio = 0.51; 95% confidence interval = 0.26–0.99; p = 0.05) and did not differ from placebo treatment (odds ratio = 1.37; 95% confidence interval = 0.23–8.21; p = 0.73). Side-effects such as “hangover” and daytime drowsiness occurred less frequently during chlormethiazole treatment compared with other drugs in three out of four studies, but differences were not significant (odds ratio = 0.24; 95% confidence interval = 0.04–1.48; p = 0.12). In conclusion, chlormethiazole showed significant effects on the duration and the quality of sleep with better tolerability if compared with other drugs in older adults with insomnia.

1 INTRODUCTION

Due to demographic developments, the population of older adults expands rapidly. The number of people aged 65 years and over who lived in the European Union increased from 82 million (17%) in 2005 to about 96 million (19%) of the EU population in 2015 (StatistischesBundesamt, 2021). Insomnia is one of the most common health problem in old age (Patel et al., 2018). Prevalence of insomnia ranges from 30% to 48% in the elderly, and is more prevalent than in the younger population (Ancoli-Israel & Cooke, 2005; LeBlanc et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2017). Patients with insomnia show reduced total sleep duration, prolonged sleep-onset latencies, an increased number of nocturnal awakenings, and prolonged periods of time awake during the night (Baglioni et al., 2014). The insufficient sleep duration and quality is associated with a high degree of suffering and impairs daily activities. Insomnia is a risk factor for somatic morbidity such as hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, myocardial infarction and chronic heart failure (Anothaisintawee et al., 2016; Laugsand et al., 2011; Palagini et al., 2013). Insomnia affects daytime performance, causes fatigue, impairs attention, causes cognitive and functional impairment, and is associated with increased risk for falls in the elderly (Ancoli-Israel & Cooke, 2005; Ancoli-Israel & Martin, 2006). In addition, insomnia is related to mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Hertenstein & Nissen, 2015; Riemann et al., 2017).

Mild insomnia should first be treated by sleep hygiene or behavioural therapy (Richter et al., 2020; Riemann et al., 2017). When these methods are inadequate, there is an indication for sleep medication. According to the guidelines, pharmacological interventions include the use of benzodiazepines (BZ) and benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRA), sedative antidepressants, antipsychotics and antihistamines (Riemann et al., 2017). Hypnotic drugs such as BZ involve the risk of habituation and decrease in effectiveness followed by increase of dose, risk of drug dependence, accumulation and hangover. Thus, hypnotic drugs are predominantly approved for a limited period of up to 4 weeks. Especially in elderly patients older than 60 years, side-effects of BZ and BZRA may outweigh the benefits (Glass et al., 2005).

Chlormethiazole (trade names Distraneurin in Germany and Switzerland, or Heminevrin in the UK) is a sedative drug developed from the thiazole portion of vitamin B1 which, compared with barbiturates, showed significantly lower toxicity (Gastager et al., 1964). It was mainly used to treat delirium and status epileptics (Gastager et al., 1964). In Germany, chlormethiazole is approved for the treatment of withdrawal syndrome in patients with alcohol dependence, predelirium, delirium tremens, sleep disorders, and agitation in elderly patients. Because of its antiepileptic properties, it can also be used in status epilepticus (Hippius, 2013). At least in elderly patients with more severe sleep disorders, chlormethiazole proved to be a good therapeutic alternative. Common side-effects of chlormethiazole taken orally include dizziness, headaches, nausea/vomiting and drowsiness. More relevant side-effects are chronic lung diseases and the possible risk of dependence.

However, beside the useful pharmacological profile and possible efficacy, chlormethiazole is not even mentioned so far as a second- or third-line option in reviews and international guidelines (Patel et al., 2018; Riemann et al., 2017). Our systematic review and meta-analysis therefore aim to investigate in the current evidence regarding efficacy and tolerability of chlormethiazole as a hypnotic in elderly patients.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

This systematic review and meta-analysis (registered in PROSPERO ID: CRD42022298978) was planned and conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, 2008) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

From their inception to 11 December 2021, we searched the following electronic databases without language restrictions: Medline (through PubMed), Scopus, the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Ovid, ZB MED and PMC. In order to obtain the most comprehensive results possible, the search was elevated for the following spelling variants of chlormethiazole (English term): clomethiazole, clomethiazol, distraneurin (trade name) and heminevrin (trade name). All databases were searched in the same way, with free combinations of “chlormethiazole” with terms like insomnia, psychiatry, elderly patients, sedatives and hypnotics to find all eligible studies. Thereon the following search term was created to search PubMed database: ([“Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Geriatrics”[Mesh] OR Geriatrics [Titel/Abstracs] AND (“Chlormethiazole”[Mesh] OR Chlormethiazole [Titel/Abstract]). Abstracts identified during the database and eligible articles were read in full to determine whether they met the eligibility criteria.

We searched for studies that fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: randomized–controlled trials (RCTs), randomized crossover trials and parallel studies about the use of chlormethiazole in elderly patients (> 60–90 years old) with insomnia. Studies from all countries published in any language were eligible. Studies on chlormethiazole treatment used for sleep disorder were eligible regardless of dose and length of treatment. Exclusion criteria were treatment of insomnia in patients ≤ 60 years, any other reason for treatment with chlormethiazole (e.g. alcohol withdrawal syndrome or delirium), use of concomitant psychotropic medication, sleep disorders due to the consequences of other organic diseases, intravenous treatment with chlormethiazole. We also received all available trials and information from CHEPLAPHARM Arzneimittel GmbH, Greifswald (Germany) as the currently only company selling chlormethiazole. No financial support or any rights regarding the use of data were associated with this support.

Two independent authors conducted study selection and data extraction. The first author screened all abstracts and papers. The last author screened a random sample of 20% of papers, using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria to confirm the reliability of selection processes. We analysed separately studies comparing chlormethiazole treatment with placebo or with a comparator (= other medical treatment of insomnia such as dichloralphenazone, temazepam, triazolam, lormetazepam, nitrazepam and thioridazine).

- sleep quality (measured by self-rating scales and/or clinician-rated scales);

- sleep duration (measured using self-rating scales and/or clinician-rated scales);

- onset of sleep (measured using self-rating scales and/or clinician-rated scales);

- safety and acceptance of the intervention (defined by number of participants with adverse events, number of drop-outs, number of patients with “hangover” and daytime sleepiness or other side-effects).

Data on participants (e.g. age, gender), methods (e.g. randomization, allocation concealment), interventions (e.g. medication and duration), control interventions (e.g. control medication, placebo, duration), outcomes (e.g. outcome measures, assessment time points) and results were extracted.

Meta-analyses were conducted by Review Manager 5 software (Version 5.3, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) via a random-effects model using the generic inverse variance method if at least two studies assessing this specific outcome were available. For continuous outcomes, standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as the difference in means between groups divided by the pooled standard deviation (Higgins & Green, 2008). Where no standard deviations were available, these were calculated from standard errors, confidence intervals, t-values, or attempts were made to obtain the missing data from the trial authors by email. A negative SMD was defined to indicate beneficial effects of chlormethiazole compared with the control intervention for all outcomes (e.g. decreased insomnia). Cohen's categories were used to evaluate the magnitude of the overall effect size, with SMD 0.2–0.5 categorized as small; SMD 0.5–0.8 as medium, and SMD > 0.8 as large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). For dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI were calculated by dividing the odds of an adverse event in the intervention group (i.e. the number of participants with the respective type of adverse event divided by the number of participants without the respective type of adverse event) by the odds of an adverse event in the control group (Higgins & Green, 2008). Where studies reported zero events in one or both intervention groups, a value of 0.5 was added to all cells of the respective study.

The I2 statistic was used to analyse statistical heterogeneity between studies, a measure of how much variance between studies can be attributed to differences between studies rather than chance. The magnitude of heterogeneity was categorized as: (1) I2 = 0%–24%: low heterogeneity; I2 = 25%–49%: moderate heterogeneity; I2 = 50%–74%: substantial heterogeneity; and I2 = 75%–100%: considerable heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, 2008). The χ2-test was used to assess whether differences in results were compatible with chance alone. Given the low power of this test, when only a few studies or studies with low sample size are included in a meta-analysis, a p-value ≤ 0.10 was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, 2008).

If at least 10 studies were included in a meta-analysis, assessment of risk of publication bias was originally planned using funnel plots generated by the Cochrane Review Manager 5 software (Higgins & Green, 2008). As less than 10 studies were included in each analysis, this was not possible. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins & Green, 2008), that assesses risk of bias on the domains selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting), and other bias. For each criterion, risk of bias was assessed as low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

3 RESULTS

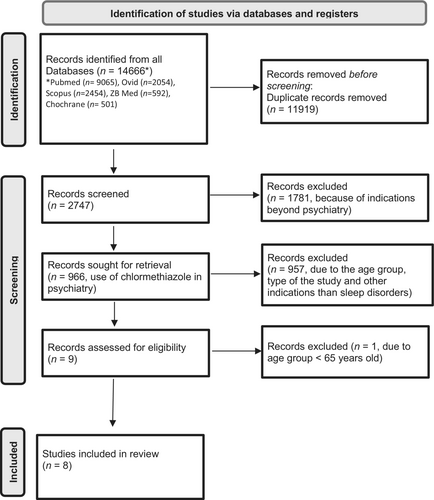

The primary search yielded 966 records. By carefully reading the abstracts and, if applicable, the full-text documents, we were able to identify overall nine RCTs. One was excluded because the study did not contain the selected age group (Haslam, 1976), resulting in eight studies with a total of 424 patients that were included in the meta-analysis (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Magnus, 1978; Middleton, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986; Figure 1).

Details from each study are presented in Table 1. Of the eight included studies, seven originated from the UK (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Magnus, 1978; Middleton, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986) and one from Finland (Harenko, 1974). One investigation was placebo-controlled and double blind randomized (Magnus, 1978). One study was three-armed and also double blind randomized using an active comparator and placebo and controlled chlormethiazole to both (Overstall & Oldman, 1987). Middleton et al. used an open study design with an active comparator (Middleton, 1978). Five studies were double blind randomized with active comparators (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986). Four studies had a crossover design (Harenko, 1974; Magnus, 1978; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986) and three studies had a parallel design (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Overstall & Oldman, 1987). One study was randomized but with an open design (Middleton, 1978). Five of the eight included studies used a placebo run-in phase in which patients showing a positive effect of the placebo were removed from the studies.

| Author, year | Study design | Duration | Number of subjects | Drop-outs | Age (years) | Gender m/f | Comparison | Outcomes | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pathy, 1975 |

Crossover Double-blind Placebo Active treatment (control) period according to random allocation |

24 nights Nights 1–3: placebo Nights 4–10: active drug Nights 11–13: placebo Nights 14–20: active drug Nights 21–24: placebo |

47 entered 38 completed the study 2 drug sequences were possible: Sequence 1 (23 patients) placebo-clo-placebo-dichloralphenazone-placebo Sequence 2 (24 patients) placebo-dichloralphenazone-placebo-clo-placebo |

9 | > 60–> 81 | m = n.a. f = n.a. |

versus placebo (run-in & wash-out periods) versus dichloralphenazone |

Onset of sleep < 60 min Clo versus Placebo: 77% versus 72% of nights Dichloralphenazone versus Placebo: 67.5% versus 72% of nights |

p < 0.05 |

Quality of sleep (nights with heavy sleep) Clo vs. Placebo: 73% vs. 57% of nights Dichloralphenazone vs Placebo: 63% vs. 57% |

p < 0.05 | ||||||||

Harenko, 1974 |

Crossover Double-blind Placebo Active treatment (control) administered in random order |

3 weeks Placebo wash- out period: 7 days Active treatment: 2 weeks (1 week nitrazepam and 1 week clo) administered in random order |

70 (2 placebo reactors; 68 entered the study) 18 interrupted temporarily for 1–3 days 44 completed without interruption |

24 of 68 18 of 24 temporarily interrupted 6 of 24: completely discontinued Clo: 1 severe hangover; 2 refused to take medication Nitr: 15 severe hangover; 3 respiratory tract infections; 1 urinary tract infection; 2 nausea |

62–91 | m = 15 f = 55 |

versus nitrazepam versus placebo |

Quality of sleep Depth of sleep: Clo 8 patients; Nitr. 25 patients Side-effects and hangover Nitrazepam > chlormethiazole Cave: hangover highly significant (Clo 2 patients; Nitr 36 patients) Drop-outs Nitrazepam > chlormethiazole Onset of sleep Clo 70 min versus Nitr. 75 min |

p n.a. p < 0.001 |

Duration of sleep Clo 8.36 hr versus Nitr. 9.18 hr |

|||||||||

Magnus, 1978 |

Crossover Double-blind Randomized Placebo |

8 weeks 2 × 1 capsule per day at 09:00 hours and at 15:00 hours -2 capsules per night: at 21:00 hours -alternation of drugs: after 4 weeks |

17 entered 17 completed |

0 | > 65 | m = n.a. f = n.a. |

versus placebo | Duration of sleep Clo increased sleep duration; approximately 1 hr of extra sleep each night |

p < 0.001 |

Disturbed behaviour → day sedative to control disturbed behaviour of demented patients |

p < 0.01 |

||||||||

items restlessness and mood items cooperation and dressing |

p < 0.05 | ||||||||

Middleton, 1978 |

Randomized Open label Active treatment (control) |

7 days | 56 of 61 entered the trial (5 patients initially had temazepam but were switched to chlormethiazole after a break of 7 days 51 completed the trial Clo: 29 entered; 24 completed the trial Tem: 32 entered; 27 completed the trial |

Clo 2; Tem. 1 |

60–95 years old |

m = 19 (clo 8; tem 11) f = 42 (clo 21; tem 21) |

versus temazepam |

Observation of nurses: -state on awakening → clo more drowsy and confused than temazepam (significant differences) |

p < 0.0002 |

-daytime dozing → clo versus temazepam (significant) |

p < 0.01 |

||||||||

Subjective observations: Morning drowsiness → Patients less often drowsy on temazepam than on clo |

p < 0.005 | ||||||||

Duration of sleep → small differences in favour of temazepam but not significant |

p < 0.05 |

||||||||

Quality of sleep → small differences in favour of temazepam but not significant |

0.1 > p > 0.05 |

||||||||

Ease of awakening → small differences in favour of temazepam but not significant |

p < 0.0002 | ||||||||

Pathy et al., 1986 |

Crossover Double-blind Parallel group Placebo Active treatment (control) |

21 days Days 1–3: Placebo/run-in period Days 4–10: Group 1 of 20 subjects temazepam Group 2 of 20 subjects clo Days 11–14: placebo/wash-out period Days 15–21: Group 1: chlormethiazole Group 2: temazepam |

40 entered 40 completed the trial |

0 | 65–90 |

m = 15 f = 25 |

versus temazepam versus baseline |

Onset of sleep → reduce sleep-onset latency significant Clo & Tem → Tem: significant carry-over effect |

p < 0.05 |

Duration of sleep → improved sleep duration with Clo & Tem → Tem: significant carry-over effect |

p < 0.05 |

||||||||

Bayer et al., 1986 |

Randomized Double-blind Parallel Active treatment (control) |

9 weeks −5-day placebo baseline period (single blind) −9 weeks of either chlormethiazole Or triazolam −5-day placebo withdrawal period (single blind) |

53 (7 only baseline data) 46 entered (considered in the statistical analysis) 46 completed the trial Clo 24 Tri 22 |

0 during the trial |

Clo 71–91 Tri 70–91 |

m = 18 f = 28 |

versus triazolam |

Onset of sleep → Improved |

p < 0.05 |

Quality of sleep → Improved Time patients were seen asleep: Significant improvement in both groups in week 1 In Clo group this was sustained but disappeared in triazolam group by week 3 Cave: daytime drowsiness (p < 0.05) associated with Tri (6 cases; clo none) |

p < 0.05 | ||||||||

Ather et al., 1986 |

Randomized Double-blind Parallel group Active treatment (control) |

4 weeks 7 days placebo (wash-out period) 4 weeks (active treatment): 2 × capsules at day 1 × capsule at night |

74 60 entered (valid for efficacy analysis) 60 completed the trial Clo group 30 Thio. group 30 |

Total 14 -6 during run-in period -5 poor compliance -2 required concurrent treatment with other psychotropic medication -3 adverse events: 1 × developed bronchopneumonia after 4 days of active treatment (thioridazin) 1 × black-out (thioridazin) 1 × oversedated (thioridazin) -0 × clo |

Clo: 65–94 Thioridazine 68–90 |

m = 12 f = 48 |

versus thioridazine | Hypnotic effects → Nocturnal awakening reduced significant in clo group than thioridazine group → Improved sleep |

p < 0.05 |

Cognitive function → Clo group with greater improvement with regard to confusion and self-care |

p < 0.05 | ||||||||

Safety → Clo better tolerated than thioridazine Thioridazine caused more adverse events |

p < 0.05 | ||||||||

Overstall & Oldman, 1987 |

Randomized Double-blind Parallel groups Three arms Placebo Active treatment (control) |

7 days | 67 (5 only baseline data) 62 entered (clo 21; lor 21; placebo 20) 58 completed the trial |

4 -clo 0 -lor 2 -placebo 2 |

> 65 years |

m = 23 f = 39 |

versus lormetazepam versus placebo |

Onset of sleep Clo reduced sleep latency significantly better than placebo; by day 7 (1 hr to > 0.5 hr) |

p < 0.05 |

Duration of sleep Clo increased sleep duration versus placebo by 1.5 hr (day 7) |

p < 0.05 | ||||||||

Quality of sleep Clo improved sleep quality on day 7 if compared to baseline |

p < 0.02 |

- Abbreviations: Clo, chlormethiazole; f, female; lor, lormetazepam; m, male; n.a., not available; nitr., nitrazepam; tem, temazepam; thio, thioridazine; tri, triazolam.

A total of 424 participants were included in the eight studies; sample size ranged from 17 to 74 (median: 54.5). Participants' mean age ranged from older than 60 to 95 years (median: 63.5–91 years). Two studies did not have precise age limits, but all patients were 65 years and older (Magnus, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987). For six studies, the average of female patients was at least 60.8%. The gender distribution was a median of 37.2% for males and 66.2% for females (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy et al., 1986). Two investigations had no information of gender distribution (Magnus, 1978; Pathy, 1975). Five studies took place in geriatric departments of different hospitals (Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986). One study was performed at a local authority residential home, except for eight hospital in-patients, who were awaiting transfer to residential care (Bayer et al., 1986). For two studies no information existed (Ather et al., 1986; Magnus, 1978).

Study durations were a minimum of 7 days and a maximum of 9 weeks. Six studies used an active comparator (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986). One study compared chlormethiazole against placebo only (Magnus, 1978). Another study compared chlormethiazole against both placebo and active comparator (Overstall & Oldman, 1987). Five studies used different BZ as active comparators – these included temazepam, triazolam, lormetazepam and nitrazepam (Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1975; Middleton, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy et al., 1986), whereby two studies used the same active comparator temazepam (Middleton, 1978; Pathy et al., 1986), which was administered in a capsule form (1–2 capsules of 10 mg per dose) according to a fixed dosing schedule (Pathy et al., 1986). Other active comparators were dichloralphenazone (Pathy, 1975) and thioridazine (Ather et al., 1986).

All studies used chlormethiazole as a hypnotic at night. For chlormethiazole, the dose used was 384 mg (two capsules, each containing 192 mg chlormethiazole) in a capsule form and 500 mg per dose as a mixture (syrup). In six studies, chlormethiazole was administered at night according to a fixed dosing schedule (384 mg, 2 × capsules of 192 mg chlormethiazole; Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Magnus, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986). In two studies, chlormethiazole was administered as mixture (syrup) with 500 mg per dose (Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978).

To control behavioural disturbances (agitation) of demented patients, in two trials chlormethiazole was not only administered at night, but also distributed throughout the day (Ather et al., 1986; Magnus, 1978). Magnus et al. followed a fixed dosing schedule: during the day at 09:00 hours and 15:00 hours at each 192 mg per capsule, and at night the dose was 2 × 192 mg per capsule (Magnus, 1978). Ather and colleagues did not use a fixed dosing schedule. The standard dose was 1 × 192 mg per capsule at 08:00 hours and 14:00 hours, and 2 × 192 mg per capsule at night. Investigators were able to reduce the dosage if necessary.

4 PRIMARY OUTCOMES

4.1 Duration of sleep

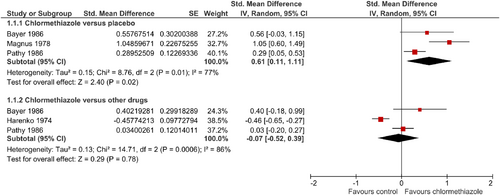

Three studies could be included in the analysis with a total of 61 patients treated with chlormethiazole and 90 with placebo (Bayer et al., 1986; Magnus, 1978; Pathy et al., 1986). Chlormethiazole significantly increased the duration of sleep when compared with placebo (SMD = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.11–1.11; Figure 2). No differences were found in comparison to other active comparators (Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Pathy et al., 1986), including 88 patients treated with chlormethiazole versus 86 treated with BZ (SMD = −0.07; 95% CI = −0.52 to 0.39; Figure 2). Considerable statistical heterogeneity occurred in both comparisons.

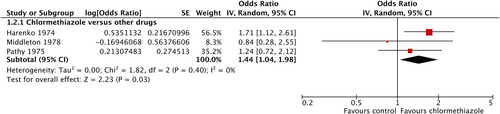

4.2 Quality of sleep/“heavy sleep”

To examine the influence of chlormethiazole on sleep quality, three studies could be included, each comparing chlormethiazole against a comparator substance. Comparators were the BZ nitrazepam and temazepam (Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978) and the sedative dichloralphenazone (Pathy, 1975). Significantly more patients in the chlormethiazole groups (total number of patients = 96) reported an adequate sleep quality or deep sleep compared with in the groups receiving other drugs (total number of patients = 100; OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.04–1.98; p = 0.03; Figure 3), without statistical heterogeneity.

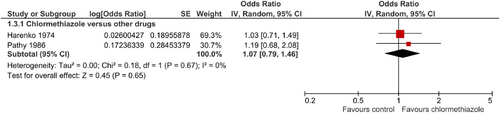

4.3 Onset of sleep

The endpoint “onset of sleep” could be investigated in only two of the eight studies, both against a comparator. Comparator substances were nitrazepam (Harenko, 1974) and temazepam (Pathy et al., 1986). A total of 64 patients on chlormethiazole were compared with 64 patients on BZ. There were no differences in time to sleep between chlormethiazole and the comparator drugs (SMD = 1.07; 95% CI = 0.79–1.46; p = 0.65; Figure 4). The studies were homogeneous.

5 SECONDARY OUTCOMES

5.1 Safety and tolerability of chlormethiazole

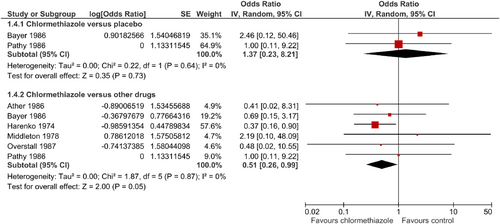

Based on six studies, drop-out rates were significantly lower under chlormethiazole treatment (n = 188) when compared with other drugs (n = 189; OR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.26–0.99; p = 0.05; Figure 5; Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy et al., 1986). However, the only two studies comparing chlormethiazole (44 patients) against placebo (n = 44) showed no significant differences (OR = 1.37; 95% CI = 0.23–8.21; Bayer et al., 1986; Pathy et al., 1986; Figure 5). There was no statistical heterogeneity.

5.2 Side-effects with special focus on “hangover” effects and drowsiness during the day

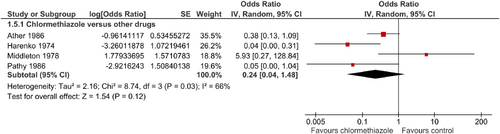

Data on “hangover” effects and daytime drowsiness could be analysed in four studies. Those effects were observed in a total of only 13 of 113 patients (11.5%) during chlormethiazole treatment. In contrast, 38 of 116 patients (32.8%) treated with other medications developed hangover effects and daytime drowsiness (Ather et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978; Pathy et al., 1986). Comparison substances were thioridazine, nitrazepam and temazepam. Thus, “hangover” effects and daytime drowsiness occurred less frequently during chlormethiazole treatment compared with other drugs in three of four studies. However, differences did not become significant (OR = 0.24; 95% CI = 0.04–1.48; p = 0.12; Figure 6).

Other side-effects, which are listed for each trial in Table 2, were in most cases mild and minor. The most common adverse effects in the elderly were dizziness, somnolence, headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, nausea/vomiting and sweating (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Middleton, 1978; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986).

| Clinical study (year) | Chlormethiazole side-effects | Active control side-effects | Placebo side-effects |

|---|---|---|---|

Pathy (1975) |

Dizziness 3 Headaches 8 Gastrointestinal symptoms 1 |

Dizziness 3 Headaches 8 Gastrointestinal symptoms 1 Nasal irritation 1 |

Dizziness 7 Headaches 8 Gastrointestinal symptoms 5 Nasal irritation 1 |

Pathy et al. (1986) |

Incontinence 1 Confusion 1 Hallucinations 1 (associated with concurrent infection) Visual disturbances 1 Vomiting 1 Nightmares 1 |

Incontinence 1 Confusion 1 Daytime drowsiness 6 (p < 0.05) Headache 1 |

Malaise 1 Muzziness 1 Confusion 1 Daytime drowsiness 1 Vomiting 1 Nightmares 1 |

Bayer et al. (1986) |

Poor concentration 1 Depression 2 Lethargy 1 Weepiness 1 Anxiety 2 Irritability 1 Dizziness 2 Headache 1 Blurred vision 1 Nausea/vomiting 2 Diarrhoea 1 Breathlessness 1 Myocardial infarction 1 Thrombophlebitis 1 |

Confusion 2 Vagueness 1 Poor concentration 2 Delusion 1 Depression 3 Lethargy 2 Weepiness 2 Anxiety 5 Irritability 2 Nausea/vomiting 1 Constipation 1 Influenza 1 Bronchopneumonia 1 Joint pains 1 Fractured femur 1 |

|

| Withdrawals during active treatments (clo and triazolam) | 1. Sudden death from myocardial infarction (week 3) 2. Dyspnoea secondary to carcinoma of lung (week 4) 3. Patient withdrew consent as a protest against her social circumstances (week 4) |

1. One patient requested withdrawal because he felt “tablets were making him nervous” (week 3) 2. Bronchopneumonia (week 3) 3. Pat. developed paranoid delusions (week 3) 4. Pat. with increasing confusion and irritability (week 4) 5. Fall resulting in fractured femur (week 4) 6. Care staff requested withdrawal because patient was “increasingly irrational, uncooperative and irritable” (week 7) Adverse events relating to the CNS were more common in the triazolam group |

|

Overstall and Oldman (1987) |

No differences between the treatment groups in the incidence and severity of adverse events, n.a. |

1 withdrawn because of vomiting 1 withdrawn because of prescribing error |

1 died on day 5 1 withdrew on day 3 because she thought the tablets kept her awake |

Harenko (1974) |

1 case: sweating at the start of treatment → Did not lead to an interruption of the trial |

5 cases: muscular weakness, nausea and worsening of the patient's mental condition → Did not lead to an interruption of the trial |

|

| Reasons for discontinuation or interruption of treatment (24 patients) | 2 cases: refusal to take medication 1 case: severe “hangover” effects |

15 cases: severe “hangover” effects, both sleepiness and muscular weakness 3 cases: respiratory tract infections 1 case: urinary tract infections 2 cases: nausea |

|

Magnus (1978) |

Few and mild n.a. |

n.a. | |

Ather et al. (1986) |

Drowsiness 10 Dizziness/unsteadiness 1 Faintness 1 Lethargy 1 Anxiety 1 Depression 1 Confusion 2 Talkativeness1 Agitation 4 Aggression 1 Noisiness 1 Non-cooperation 1 Incontinence 1 Vomiting 1 Diarrhoea 2 |

Drowsiness 17 (p < 0.05) Dizziness/unsteadiness 7 (p < 0.05) Collapse/black-out 2 Slurred speech 1 Immobility 1 Insomnia 1 Depression 1 Talkativeness1 Agitation 1 Aggression 1 Incontinence 1 Vomiting 1 Diarrhoea 1 Bronchopneumonia 1 |

|

Middleton (1978) |

In both groups, adverse reactions were few and predictable (most common: drowsiness during the day) 2 patients removed from the study because of increasing confusion and daytime drowsiness, respectively |

1 patient complained of nasty taste in the morning 1 patient became incontinent during the trial |

- Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; n.a., no data available.

6 RISK OF BIAS

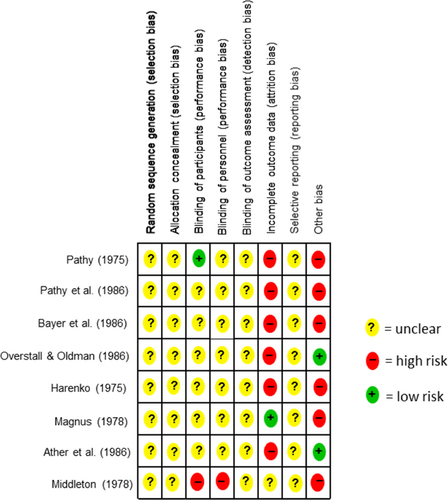

An overview of the risk of bias for the individual studies is illustrated in Figure 7. Adequate randomization and concealed allocation “selection bias” were rated as “unclear” in all eight included studies. No other detail was given for bias on any of the studies. Regarding “performance bias”, six studies did not include further information on blinding of patients (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Magnus, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy et al., 1986). Pathy (1975) was rated as a low risk and Middleton (1978) as high risk (Middleton, 1978; Pathy, 1975). With reference to the blinding of subjects’ “performance bias”, there was no information in seven studies, so an “unclear” was assigned here (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Magnus, 1978; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986). In Middleton's investigation, subjects were unblinded (Middleton, 1978). In all eight included studies, there was no information on blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias). Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) were rated as high risk in six studies (Ather et al., 1986; Bayer et al., 1986; Harenko, 1974; Overstall & Oldman, 1987; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986), low risk in Magnus, and “unclear” in Middleton (Magnus, 1978; Middleton, 1978). There was no accessible study protocol for any of the eight studies “reporting bias”, therefore all eight studies were rated as “unclear” regarding “selective reporting”. Six studies were classified as high risk for other bias. For this reason, studies with “crossover” designs were rated as high risk, because the substances may not be adequately washed out (Harenko, 1974; Magnus, 1978; Pathy, 1975; Pathy et al., 1986). Regarding Pathy (1975), high risk was assigned because of the many placebo reactors. Bayer et al. (1986) was classified as high risk because of a possible measurement error in reading the data. Here, the data were extracted from an image of the paper because we do not have access to the raw data. The study by Middleton (1978) reported five patients who changed medication during the study. The number of participants in the study by Magnus (1978) is small, and for this, as for all other included studies, we lack a flowchart and study registration to understand what the actual course was. In two studies no further risk of bias was apparent, which is why they were rated as low risk (Ather et al., 1986; Overstall & Oldman, 1987).

7 DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the efficacy of chlormethiazole with respect to its hypnotic effects and use as a sedative in elderly patients, including also discontinuation rates and side-effects such as daytime drowsiness and “hangover”. Due to the large heterogeneity of the studies, different outcome parameters were defined with sleep duration, sleep-onset time, sleep quality, drop-out rates and hangover effects. Overall, chlormethiazole showed a significant better improvement of sleep duration when compared with placebo, and a superiority in sleep quality (heavy sleep) when compared with the hypnotics nitrazepam and temazepam. Duration to fall asleep or “onset of sleep” did not differ compared with other sedatives. Due to insufficient data, a meta-analysis on this outcome parameter compared with placebo was not possible. Regarding safety and tolerability, discontinuation rates were similar to placebo but significantly lower when compared with other drugs. While “hangover” or drowsiness were reported significantly less frequently with chlormethiazole, the differences to comparators became not significant due to the large study heterogeneity. In summary, our analyses regarding the effect of chlormethiazole in people over 60 years on insomnia reveal positive effects on sleep duration and sleep quality combined with a superior safety profile, with significantly lower drop-out rates and less hangover effects and daytime drowsiness. Regarding general safety aspects about the risk of chlormethiazole to induce tolerance or drug dependence, trials did not include necessary information. However, all studies had insufficient treatment duration or observation time to expect the development of drug dependence.

Chlormethiazole was introduced in Germany in 1961 with excellent results in the treatment of alcohol delirium (Athen et al., 1977; Bergener, 1966; Glatt, 1980; Glatt & Frisch, 1969; Huffmann & Leven, 1965; Salum, 1966; Sattes, 1964). Chlormethiazole has additionally been used for hyperactive delirium in geriatrics. It was also considered as a well-tolerated sedative, mainly because of the absence of disturbing side-effects (Bergener & Neller, 1966; Gastager et al., 1964; Zgaga, 1971). According to Gastager et al., side-effects during the treatment with chlormethiazole were minor compared with the good efficacy, and led to discontinuation of the drug only in a few cases (Gastager et al., 1964). Witts and colleagues also reported lower toxicity and a more acceptable spectrum of side-effects in a pharmacokinetic study of chlormethiazole (Witts et al., 1979). Prolonged use of chlormethiazole may result in withdrawal symptoms especially if patients increased dosage and treatment was discontinued (Reilly, 1976). There are also case reports with chlormethiazole dependence (Gregg & Akhter, 1979). The main problems with chlormethiazole dependence or intoxication came from reports of patients with primary drug addiction (Braunwarth, 1990), which seems to be less relevant in elderly patients or patients with symptoms of dementia. In fact, Zgaga found no evidence of drug dependence in 50 patients of a nursing home (age 70–90 years) after prolonged treatment for 5 months (Zgaga, 1971). The risk of habituation and dependence was also not pronounced in another trial about the use of chlormethiazole for organic psychosis and agitation in geriatric patients (Sattes, 1969). Nevertheless, due to reports of drug dependence, the drug Commission of the German Medical Association calls for a strict indication for chlormethiazole, with only brief use and only in inpatients (Keup, 1977).

Other serious side-effects such as cardiac arrest and respiratory depression are more associated with intravenous treatment of delirium tremens with chlormethiazole (Gsell et al., 1972). When the drug is administered orally, these side-effects are rather rare. Common side-effects of oral therapy with chlormethiazole include increased salivary and bronchial secretions, which can lead to severe respiratory depression in patients with impaired respiratory function, drowsiness, dizziness, headache, palpitations, sensory disturbances such as numbness or tingling, itching, rashes, conjunctivitis, nausea/vomiting and fatigue. Occasionally, there are gastrointestinal disturbances, burning sensation in the throat and nose, rhinitis sensation and cough irritation, which decrease in intensity or subside completely after a few days (more common in younger age groups; Castleden et al., 1979; Haslam, 1976). Very rarely, severe respiratory and cardiovascular depression occur. An overdose of chlormethiazole is associated with respiratory depression (Illingworth et al., 1979). Chlormethiazole appears to be safe in persons with normal respiratory function. However, it cannot yet be used for people with hypoxic chronic obstructive lung disease, whose insomnia is often secondary to their underlying disease (Calverley et al., 1982) and whose nocturnal hypoxia may be exacerbated by the administration of sedatives, as is recommended for all commonly used hypnotics, especially the BZ (Calverley et al., 1984).

Notable side-effects include clouded consciousness leading to coma, central respiratory depression leading to respiratory arrest, cardiovascular failure, cardiac arrest and hypotensive blood pressure reactions (Hippius, 2013). In 1984, 38 deaths were reported from the literature in which chlormethiazole overdose was the primary cause. Of these, 18 cases were studied in 1978–1983 in which chlormethiazole overdose had caused death along with other substances. Chlormethiazole poisoning results in coma, respiratory depression, hypotension, hypothermia, and increased salivation similar to severe barbiturate poisoning (Klug & Schneider, 1984). According to Benkert and Hippius, a development of dependence is already possible after relatively short-term prescription of chlormethiazole. Therefore, chlormethiazole should be prescribed for a maximum of 14 days and not on an outpatient basis, but only under inpatient conditions (Hippius, 2013). However, according to Zgaga et al., no tolerance and “drug dependence” or addiction was observed in geriatric patients during treatment with chlormethiazole (Bayer et al., 1986; Dehlin, 1986; Zgaga, 1971). Chlormethiazole dependence usually occurs secondary to existing alcohol dependence. However, Gregg and Akhter also found addicts in whom dependence was not secondary to alcoholism (Gregg & Akhter, 1979). Therefore, treatment with chlormethiazole is given under controlled inpatient conditions. This applies to the treatment of predelirium, delirium tremens and acute withdrawal symptoms, as well as to the treatment of confusion, agitation and restlessness in patients with cerebral-organic psychosyndrome in old age (Braunwarth, 1990; Hippius, 2013; product information).

Due to the potential for dependence, current recommendations are for a maximum treatment duration of 14 days or longer only if delirium persists and the therapeutic benefit is weighed against the risk of chlormethiazole dependence (Braunwarth, 1990; Hippius, 2013; product information).

However, patient groups such as patients with asthma are particularly at risk with regard to possible respiratory depression. Severe chlormethiazole intoxication may result in comatose states with subsequent cardiac arrest, increased secretions in the upper respiratory tract, centrally triggered respiratory depression, hypotension, hypothermia, and depression of the cardiovascular system (Calverley et al., 1982; Calverley et al., 1984; Castleden et al., 1979; Illingworth et al., 1979). Because of this, close medical monitoring of patients is essential in outpatient therapy, such as that used for sleep disorders.

Chlormethiazole is not listed as a treatment option in the current European guidelines for sleep disorder/insomnia (Riemann, et al., 2017). However, due to the shown efficacy in this meta-analysis and positive tolerability combined with the reported low chronic toxicity and acceptable spectrum of side-effects (Witts et al., 1979), chlormethiazole should be considered as a treatment option in difficult cases of sleep disturbances in the elderly with lack of response to other agents. Currently, BZ are the drugs of choice for sleep disorders, even in patients 60 years and older. An important advantage of BZ over chlormethiazole is their wide therapeutic range. Adaptation to individual therapeutic needs is therefore more achievable with BZ. This potentially makes the use of BZ in outpatient therapy easier. However, long-term use in the treatment of chronic sleep disorders leads to the development of tolerance, which results in inadequate effect and a risk of dependence (Hohagen et al., 1993). This development of tolerance does not occur in the literature with chlormethiazoles over longer periods of administration (Bayer et al., 1986; Dehlin, 1986). Both drugs may cause rebound effects after discontinuation, suggesting a worsening of sleep. However, we found no evidence of disturbed sleep in the subjective assessment of patients after discontinuation of chlormethiazoles in the eight studies analysed, except for the first night after discontinuation.

In addition, BZ often do not work in severe sleep disorders with agitation and confusion syndromes. Therefore, it seems important to identify other possible alternatives. Due to the pharmacological profile of chlormethiazole with a very good sedative effect and low side-effect and interaction potential shown in studies several times, especially in the elderly, chlormethiazole seems to be a relevant option for sleep disorders that are difficult to treat, especially also for agitation and behavioural changes. Because of the side-effects and risks, in severe syndromes and somatic comorbidities, an inpatient setting may also be individually appropriate and safer.

Sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of chlormethiazole on agitation and confusion states (Ather et al., 1986; Magnus, 1978). In elderly patients with dementia, chlormethiazole showed statistically significant superiority over placebo in the clinical aspects of sleep, agitation, mood, vigilance and performance (Magnus, 1978). The differences between chlormethiazole and placebo in mobility, orientation, communication and self-care were not statistically significant (Magnus, 1978). Ather et al. compared chlormethiazole and thioridazine in agitated elderly with confusional states. Chlormethiazole was better tolerated here than thioridazine. Both agents resulted in significant improvement in exercise and performance capacity, and showed comparable improvements in agitation versus intake levels. Confusional states and nocturnal awakenings were significantly better controlled by chlormethiazole. In addition, the frequency of nocturnal awakenings was significantly reduced in the chlormethiazole group (Ather et al., 1986). Accordingly, chlormethiazole proved to be an effective hypnotic (sedative) for both nighttime and daytime control of behavioural disturbances in elderly patients with dementia. It showed statistically significant superiority over placebo in the clinical aspects of sleep, agitation, mood, vigilance and performance.

7.1 Limitations

We found a relatively small number of RCTs with relatively small sample size. Overall, the quality of the studies, due to the overall very distant publication date and the partly insufficiently described methodology (all were conducted in the 1970s and 1980s, partly no information on the randomization procedure, etc.), has to be classified as unclear. In addition, there were no available study protocols or registrations in study registries, so it could not be assessed whether they actually reported all outcomes or possibly published mainly significant results. While randomization sequence was not adequately described in any of the studies, this does not exclude the possibility that randomization may meet today's quality standards. Related to the age of the studies found, there was no possibility to access the raw data, so that the information for the calculation of the meta-analysis was partly insufficient. Biases may have arisen over the latter due to the subjective assessments of patients and staff as well as the definition of, for example, the term “sleep quality”. In addition, because of differences in primary outcomes (we followed investigators' choices for their primary outcomes) among the few available studies, in some cases only three of the eight studies could often be included in the analysis. In addition, not all studies were placebo-controlled and used different inclusion procedures (placebo run-in and wash-out phases).

8 CONCLUSION

Medication therapy for sleep disorders such as insomnia, especially in elderly patients, remains a major challenge. Our work shows significant improvement in sleep duration with chlormethiazole compared with placebo in patients over 60 years old with sleep disorders, and significantly better sleep quality compared with comparator agents such as the BZ nitrazepam and temazepam. In terms of safety and tolerability, the meta-analysis showed overall lowest drop-out rates for chlormethiazole, and significant superiority in terms of hangover effect and daytime drowsiness compared with other drugs. Currently, chlormethiazole is not mentioned in the guidelines for the treatment of sleep disorders. Based on this meta-analysis, as well as the existing literature and experience from other clinical settings, the use of chlormethiazole in elderly patients with sleep disorders seems quite conceivable, at least as a further option for inpatients but also for outpatient settings with close monitoring. Despite the unclear methodological rigour, chlormethiazole, especially compared with BZ, could represent an alternative in the treatment of persistent or severe sleep disorders in the elderly. Especially in cases of unclear delirious syndromes or agitation, the effect may be stronger than with BZ, whose use should be as restrictive as possible in the elderly. Nevertheless, possible side-effects and risks must be considered.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Marwa Al Juburi: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; validation; visualization; writing – original draft. Holger Cramer: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Martin Schäfer: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest was identified by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors did not receive financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.