It's past your bedtime, but does it matter anymore? How longitudinal changes in bedtime rules relate to adolescents’ sleep

Summary

This study investigated how changing or maintaining parent-set bedtimes over time relates to adolescents’ sleep timing, latency, and duration. Adolescents (n = 2509; Mage = 12.6 [0.5] years; 47% m) self-reported their sleep patterns, and whether they had parent-set bedtimes on two separate occasions in 2019 (T1; 12.6 years) and 2020 (T2; 13.7 years). We identified four groups based on parent-set bedtimes: (1) bedtime rules at both T1 and T2 (46%, n = 1155), (2) no bedtime rules at T1 nor T2 (26%, n = 656), (3) bedtime rules at T1 but not T2 (19%, n = 472), (4) no bedtime rules at T1 but a parent-set bedtime at T2 (9%, n = 226). As expected, the entire sample showed that bedtimes generally became later and sleep duration shorter across adolescence, but the change differed among the groups. Adolescents whose parents introduced bedtime rules at T2 reported earlier bedtimes and longer sleep duration (~20 min) compared with adolescents with no bedtime rules at T2. Importantly, they no longer differed from adolescents who consistently had bedtimes across T1 and T2. There was no significant interaction for sleep latency, which declined at a similar rate for all groups. These results are the first to suggest that maintaining or re-introducing a parent-set bedtime may be possible and beneficial for adolescents’ sleep.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although adolescents strive for autonomy as they develop, keeping a set bedtime is consistently associated with earlier bedtimes and a longer sleep duration (see Khor et al., 2021). In addition, studies have found that the benefits of earlier parent-set bedtimes extend to adolescents’ daytime functioning (e.g., daytime alertness, better mood; Khor et al., 2021; Gangwisch et al., 2010). Although most studies in this area are cross-sectional, a few longitudinal studies support the positive effect of parent-set bedtimes on later sleep outcomes for adolescents (Maume, 2013; Peltz et al., 2020; Tashjian et al., 2019). Furthermore, a comprehensive meta-analysis of risk and protective factors for adolescents’ sleep identified parent-set bedtimes as the most powerful protective factor for sufficient sleep duration, along with sleep hygiene (Bartel et al., 2015). Yet, no study to date has investigated the impact of changing parent-set bedtimes on adolescents’ sleep. The present longitudinal study observed how changes in parental rules about bedtimes over time were associated with changes in adolescent sleep outcomes.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to examine the impact of changing or maintaining bedtime rules on adolescents’ weekday sleep timing, latency, and duration from age 12–13 (T1) to 13–14 (T2) in a large sample of Australian adolescents. We compared four groups of adolescents on their self-reported sleep; adolescents with bedtime rules at both T1 and T2, adolescents with no parent-set bedtimes at both time points, and adolescents whose parent-set bedtimes changed from T1 to T2 (either from “yes to no” or “no to yes”).

2 METHOD

2.1 Design and participants

This study used data from the “Health4Life” study, a large cluster randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of an eHealth intervention to improve lifestyle risk factors among Australian secondary school students (Teesson et al., 2020). Participants were Year 7 students from 71 participating schools across New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD), and Western Australia (WA). Only students allocated to the control condition (n = 3030) were included in the current study to avoid contamination effects from the intervention. The analytical sample of the current study consisted of 2509 adolescents with data on parent-set bedtimes at both time points (Mage at baseline = 12.6 years [range = 11–14], SD = 0.5; 47.1% boys, 1% “prefer not to say”, and 0.6% “non-binary”). The majority were born in Australia (86.3%) and who spoke English as the main language at home (93.3%). The average socioeconomic status (SES) was 9.43 (range 0–13; SD = 1.86).

Adolescents with complete information on parent-set bedtimes at T1 and T2 did not differ significantly from those with missing information in age, gender, SES, county of birth, language spoken at home, region, bedtimes, sleep onset latency, and duration (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.06).

The trial received ethics approval from 10 relevant committees (University of Sydney HREC2018/882, NSW Department of Education SERAP 2019006, University of Queensland 2019000037, Curtin University HRE2019-0083 and several Catholic Diocese committees). Further details, including recruitment and consent procedures are in the published study protocol (Teesson et al., 2020).

2.2 Sociodemographic variables

Adolescents answered questions about age (calculated from date of birth), sex assigned at birth (including “male”, “female”, and “prefer not to say”), cultural and linguistic diversity (i.e., country of birth and language spoken at home), and relative socioeconomic position (Family Affluence Scale III [FASIII]) (Torsheim et al., 2016). The FASIII generates a summed score across indicators of familial wealth (e.g., number of computers, number of bathrooms in home, etc.) as a proxy for familial SES that is easier for adolescents to report.

2.3 Sleep

Adolescents' sleep was measured using the Modified Sleep Habits Survey (Short et al., 2013). Referring to the past week, and separately for weekdays and weekends, adolescents were asked to report the time they usually: (1) went to bed, (2) attempted sleep, (3) took to fall asleep, (4) were awake during the night, and (5) woke up in the morning. In the present study, we focussed on weekday sleep and derived several sleep parameters, including first sleep attempt (which we refer to as bedtime), sleep onset latency (SOL), wake after sleep onset (WASO), total sleep time (TST; i.e., time between falling asleep and wake up in the morning, minus WASO).

2.4 Parent-set bedtimes

Adolescents were asked whether their parents had bedtime rules for them “Do your parents set your bedtime on school nights?” (yes/no). Close to half of the sample reported a parent-set bedtime at both T1 and T2 (46%), 26% reported no bedtime rules at both times, 19% reported bedtime rules at T1 but not T2, and 9% reported bedtime rules at T2 but not T1.

3 RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics and sleep patterns of each parent-set bedtime group are presented in Table 1. We ran three unadjusted general linear models (GLM) for bedtimes, sleep duration, and sleep onset latency in SPSS (v 26).

| BT rules at T1 & T2 | No BT rules at T1 & T2 | BT rules at T1 only | BT rules at T2 only | Test of difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean (SD)/% | Mean (SD)/% | Mean (SD)/% | Mean (SD)/% | F/χ2(df) |

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Age | 12.6 (0.5)a | 12.7 (0.5)a | 12.7 (0.5)a | 12.6 (0.5)a | F(3) = 2.57 |

| Sex (male) | 45.7%a | 48.2%a | 46.4%a | 50.4%a | χ2(6) = 3.30 |

| Country of birth (Aus) | 89.0%a | 84.1%b | 85.8%ab | 78.3%b | χ2(3) = 21.78*** |

| English main language at home | 96.3%a | 88.8%b | 92.8%b | 92%b | χ2(3) = 38.05*** |

| SES | 9.37 (1.75)a | 9.56 (1.86)%a | 9.42 (1.71)%a | 9.54 (2.03)%a | F(3) = 1.60 |

| Sleep | |||||

| BT T1 | 21:20 (1:10)a | 21:56 (1:20)b | 21:40 (1:19)c | 21:45 (1:33)c | F(3) = 33.42*** |

| BT T2 | 21:50 (1:19)a | 22:24 (1:22)b | 22:18 (1:19)b | 21:58 (1:21)a | F(3) = 29.97*** |

| SOL T1 | 0:42 (0:48) | 0:36 (0:47) | 0:40 (0:48) | 0:40 (0:52) | F(3) = 1.77 |

| SOL T2 | 0:39 (0:46)a | 0:30 (0:46)a | 0:34 (0:47)a | 0:33 (0:42)a | F(3) = 4.38** |

| WASO T1 | 0:19 (0:35) | 0:18 (0:35) | 0:19 (0:36) | 0:21 (0:41) | F(3) = 0.43 |

| WASO T2 | 0:14 (0:30) | 0:18 (0:39) | 0:17 (0:38) | 0:19 (0:42) | F(3) = 1.96 |

| WT T1 | 6:34 (0:38) | 6:37 (0:50) | 6:37 (0:43) | 6:36 (0:43) | F(3) = 0.45 |

| WT T2 | 6:31 (0:44) | 6:32 (0:54) | 6:34 (0:43) | 6:37 (0:44) | F(3) = 1.14 |

| Sleep duration T1 | 498 (103)a | 475 (98)b | 486 (102)ab | 486 (99)ab | F(3) = 6.80*** |

| Sleep duration T2 | 484 (99)a | 461 (91)b | 461 (98)b | 481 (102)a | F(3) = 10.27*** |

- Note: Different superscript letters denote the subgroups were significantly different from each other. Test of overall difference: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

- Abbreviation: BT, Bedtime (hh:mm); SOL, sleep onset latency (hh:mm); SES, socioeconomic status; WASO, wake after sleep onset (hh:mm); WT, wake time (hh:mm); sleep duration (minutes).

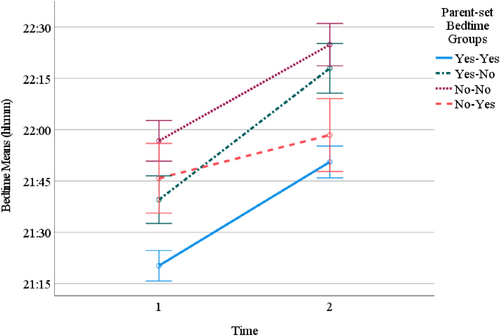

3.1 Bedtimes

Bedtimes became later in the whole sample over time [F(1, 2467) = 165.57, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06], and there was a significant interaction between time and parent-set bedtimes [F(3, 2467) = 4.26, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.005], meaning that a change in rules impacted how much later adolescents attempted to sleep (Figure 1). Post-hoc tests indicated that at T1, adolescents with bedtime rules at both T1 and T2 reported the earliest bedtimes compared with all other groups. Both groups of adolescents with parent-set bedtimes at T1 reported significantly earlier bedtimes compared with adolescents with no bedtime rules at T1 and T2 [FT1(3, 2467) = 33.17, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04]. At T2, bedtimes were significantly later when parents had no bedtime rules compared with the other groups. The group that consistently had bedtime-rules and the group introducing rules at T2 were not statistically different [FT2(3, 2467) = 30.06, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04].

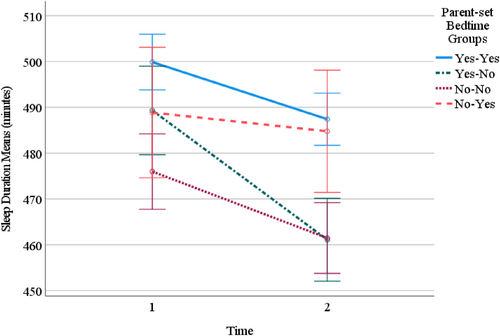

3.2 Sleep duration

There was a significant main effect of time on sleep duration, which decreased for the overall sample, [F(1, 2188) = 31.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.014], and also a significant interaction between time and parent-set bedtimes [F(3, 2188) = 3.20, p = 0.023, η2 = 0.004], meaning that adolescents’ sleep duration changed at different rates across parent-set bedtime groups (Figure 2). Post-hoc tests indicated that at T1, adolescents whose parents maintained bedtime rules across T1 and T2 reported longer TST than adolescents with a consistent lack of parent-set bedtimes. No other differences existed among the groups at T1, [FT1(3, 2188) = 7.07, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01]. At T2, adolescents who did not have bedtime rules (either changed from “yes” to “no”, or had no rules at both T1 and T2) slept significantly less than adolescents whose parents set bedtimes (either changed from “no” to “yes” at T2, or maintained bedtime rules from T1 to T2), [FT2(3, 2188) = 13.70, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.02].

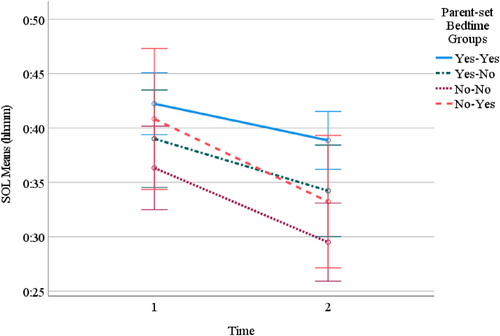

3.3 Sleep onset latency

Sleep latency decreased for the overall sample from T1 to T2 [F(1, 2368) = 21.39, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.009], but there was no significant interaction between time and parent-set bedtimes [F(3, 2368) = 0.85, p = 0.467, η2 = 0.001], meaning that this change was similar across the different groups (Figure 3).

3.4 Sociodemographic characteristics among families with different bedtime rules

As seen in Table 1, there were a number of significant differences between the groups, which may help to understand which parents impose a bedtime. Adolescents whose parents introduced bedtime rules at T2 were not significantly different from the families with bedtimes at both T1 and T2, nor from the families without set bedtimes at T2. While socioeconomic status, sex distribution, and age were similar across all groups, some cultural and linguistic differences existed between the group that maintained bedtime rules and the other families. Families with bedtimes at both T1 and T2 were the most homogeneous group in terms of children being born in Australia and speaking English at home.

4 DISCUSSION

This study is the first to investigate adolescents’ sleep patterns over time as a function of their parent-set bedtimes. We found a significant interaction between parent-set bedtimes and adolescents’ bedtimes and sleep duration, but not sleep onset latency. This is not surprising given that SOL, compared with bedtimes and ultimately TST, might be less behaviourally determined and instead tied to biological and cognitive-emotional underlying factors (i.e., once bedtimes are set, it might still be difficult for adolescents to fall asleep before sleep homeostatic pressure has accumulated, and/or to stop negative thinking which might occur while waiting to fall asleep; Hiller et al., 2014). On the other hand, parent-set bedtimes (both those maintained across T1 and T2, or introduced at T2 only) were associated with earlier bedtimes and longer sleep duration, supporting data from a recent review and meta-analysis (Khor et al., 2021).

The novelty and important message of this study is tied to the group changing from no parent-set bedtime at T1, to a set bedtime at T2. These adolescents showed earlier bedtimes and longer sleep duration than adolescents with no rules at T2, yet were not significantly different from adolescents reporting parent-set bedtimes at both time points. It has often been assumed that once bedtime autonomy is granted, adolescents would not accept a re-introduction of bedtime rules. However, the results of this study suggest there are some families who are successfully introducing or re-introducing bedtimes in adolescence, which appears to slow the trend towards delaying bedtimes and decreasing sleep duration. This may be in line with recent qualitative data, where adolescents are open to receiving support for their sleep from parents (Godsell & White, 2019; Jakobsson et al., 2022). Thus, instilling a bedtime may be a form of such parental support.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size and the longitudinal design, which captured natural changes in parent-set bedtimes, resembling a quasi-experimental design. However, one question that should be further investigated is whether pre-existing individual differences of adolescents in the different groups might explain our results. Adolescents whose parents re-introduced bedtimes at T2 did not differ from the other groups at T1 in terms of sleep nor sociodemographic variables, but there might be other differences that were not explored in this study. We urge researchers to ask adolescents whether their parents have reintroduced bedtime rules, or even perform intervention work in this vein, to understand the characteristics of families who are able to promote healthy sleep by successfully reintroducing a bedtime.

Despite the limitations and in the context of a growing body of research supporting the positive impact of parent-set bedtimes on adolescents’ sleep, this study suggests that sleep interventions might not only aim at maintaining but also re-introducing bedtime rules, even during mid-adolescence. We found an average difference of ~20 min between adolescents with and without parent-set bedtimes at T2, a sleep gain hardly obtained with more intensive interventions than informing parents (Bonnar et al., 2015), such as school-based sleep education programmes delivered for up to 5 weeks (see Rigney et al., 2021). Therefore, we encourage public health recommendations to highlight the beneficial effects of maintaining bedtime rules into adolescence.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. V. Bauducco: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. L. A. Gardner: Funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; writing – review and editing. K. Champion: Funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; writing – review and editing. N. Newton: Funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; writing – review and editing. M. Gradisar: Conceptualization; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Health4Life study was led by researchers at the Matilda Centre at the University of Sydney, Curtin University, the University of Queensland, the University of Newcastle, Northwestern University, and UNSW Sydney: M. Teesson, N.C. Newton, F.J. Kay-Lambkin, K.E. Champion, C. Chapman, L.K. Thornton, T. Slade, K.L. Mills, M. Sunderland, J.D. Bauer, B.J. Parmenter, B. Spring, D.R. Lubans, S.J. Allsop, L. Hides, N.T. McBride, E.L. Barrett, L.A. Stapinski, L. Mewton, L.E. Birrell, C. Quinn, and L.A. Gardner.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The Health4Life study was funded by the Paul Ramsay Foundation and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council via Fellowships (K. Champion, APP1120641; MT, APP1078407; and N. Newton, APP1166377) and via a Centre of Research Excellence in the Prevention and Early Intervention in Mental Illness and Substance Use (PREMISE; APP11349009). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge all the research staff who have worked across the study, as well as the schools, students, and teachers who participated in this research. The research team also acknowledges the assistance of the New South Wales Department of Education (SERAP 2019006), the Catholic Education Diocese of Bathurst, the Catholic Schools Office Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle, Edmund Rice Education Australia, the Brisbane Catholic Education Committee (373), and Catholic Education Western Australia (RP2019/07) for access to their schools to conduct this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M. Gradisar reports that he is the CEO of WINK Sleep Pty Ltd which provides professional training for the treatment of sleep disorders, and is employed by Sleep Cycle AB, a listed company whose app tracks sleep.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.