The role of rumination in the relationship between symptoms of insomnia and depression in adolescents

Summary

There is a strong relationship between the symptoms of insomnia and depression, however, little is understood about the factors that mediate this relationship. An understanding of these underlying mechanisms may inform the advancement of existing treatments to optimise reductions in insomnia and depression when they co-occur. This study examined rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep as mediators between symptoms of insomnia and depression. It also evaluated the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) on rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep, and whether these factors mediated the effect of CBT-I on depressive symptoms. A series of mediation analyses and linear mixed modelling were conducted on data from 264 adolescents (12–16 years) who participated in a two-arm (intervention vs. control) randomised controlled trial of Sleep Ninja®, a CBT-I smartphone app for adolescents. Rumination, but not unhelpful beliefs about sleep, was a significant mediator between symptoms of insomnia and depression at baseline. CBT-I led to reductions in unhelpful beliefs about sleep, but not in rumination. At the between-group level, neither rumination, nor unhelpful beliefs about sleep emerged as mechanisms underlying improvement in depression symptoms, however, rumination mediated within-subject improvements following CBT-I. The findings suggest rumination links symptoms of insomnia and depression and provide preliminary evidence that reductions in depression following CBT-I occurs via improvements in rumination. Targeting rumination may improve current therapeutic approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep disturbance is an important risk factor for depression onset and relapse (Baglioni et al., 2011; Franzen & Buysse, 2008; Lovato & Gradisar, 2014). This has prompted interest in targeting sleep as a means of indirectly reducing depression and mental illness (Freeman et al., 2017; Werner-Seidler et al., 2023). Indeed, treatments targeting sleep, such as cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), improve both sleep and depression (Christensen et al., 2016; Cunningham & Shapiro, 2018). However, little is understood about the mechanisms that link sleep disturbance and depression. Similarly, the mechanisms underlying improvement in depression following CBT-I is not known.

A factor that is important in both insomnia, the most prevalent sleep disorder (APA, 2013), and depression is rumination. Rumination was originally conceptualised in the context of depression and defined as a repetitive style of thinking focussed on the causes, meanings, and consequences of depressive symptoms and mood (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Watkins, 2008). Rumination exacerbates and prolongs negative affective states and predicts depression onset, severity, treatment responsiveness and relapse (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Topper et al., 2010). It has also been established as a mechanism of change in depression interventions (Domhardt et al., 2021). However, more contemporary conceptualisations recognise rumination as an important variant of repetitive negative thinking. Specifically, rumination is a transdiagnostic process implicated in many mental disorders, including insomnia, and thus, thought content is not limited to depression-related material (Tanner et al., 2013).

Harvey's (2002) influential cognitive model of insomnia describes the role of rumination, alongside unhelpful beliefs about sleep, as an important mechanism underlying insomnia (Harvey, 2002; Harvey et al., 2005). The model is widely supported by empirical data. For example, rumination is more prevalent and distressing in people with insomnia compared with good sleepers (Harvey, 2010), is associated with greater sleep disturbance (Clancy et al., 2020; Nota & Coles, 2015; Richardson et al., 2019; Yeh et al., 2015), predicts sleep disturbance in longitudinal studies, and disrupts naps and night-time sleep (Gómez-Odriozola & Calvete, 2021; Guastella & Moulds, 2007; Harvey et al., 2005). However, while the gold-standard psychological treatment for insomnia, CBT-I (van der Zweerde et al., 2019) effectively reduces unhelpful beliefs about sleep, it has little effect on rumination in adults (Ballesio et al., 2021), suggesting that CBT-I does not effectively target this important mechanism.

It has been proposed that rumination is not only a mechanism underlying both insomnia and depression, but that it plays a critical role in mediating the relationship between them (Lovato & Gradisar, 2014). In their model, Lovato and Gradisar (2014) stipulate that more time spent awake in bed, in an environment free of visual and auditory distraction, the greater the opportunity for rumination. In turn, rumination simultaneously increases pre-sleep hyperarousal, leading to further difficulties with sleep onset, duration, and quality, which perpetuates a cycle of increased rumination and sleep difficulties, ultimately leading to the development of symptoms of depression (Lovato & Gradisar, 2014). Adolescents are particularly vulnerable, as the onset of puberty is associated with a delay in the circadian system (i.e., core body temperature and melatonin rhythms), contributing to a delay in sleep onset resulting in more time awake in bed, which provides a greater opportunity for rumination (Tarokh et al., 2019).

There is preliminary support for this model in adolescents with delayed sleep–wake phase sleep disorder (DSWPD). DSWPD is characterised by sleep and wake times two or more hours later than is conventional, often resulting in sleep onset difficulties (Sateia, 2014). Like individuals with insomnia, those with DSWPD demonstrate increased rumination (and worry) compared with good sleepers (Cunningham & Shapiro, 2018; Richardson et al., 2016). Research has found that pre-sleep worry and rumination accounts for the relationship between sleep onset difficulties and depression (Richardson & Gradisar, 2022). Furthermore, the intervention under investigation, bright light therapy, led to improved symptoms of depression, sleep onset difficulties, and worry/rumination (Richardson & Gradisar, 2022). We are not aware of any studies examining rumination as a mediator between insomnia and depression in adolescents with elevated insomnia symptoms. Furthermore, the capacity of CBT-I to reduce rumination in adolescents and whether rumination mediates the effects of CBT-I on depression has not been established. The focus of the current study is to address these questions to determine the importance of rumination as a treatment target to improve both depression and insomnia outcomes. If, as in adults, CBT-I does not effectively reduce rumination, it may be the case that additional, rumination-specific approaches might be needed to address this residual risk factor.

- Do rumination and/or unhelpful beliefs about sleep mediate the association between symptoms of insomnia and depression?

- What is the effect of CBT-I on rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep?

- Are rumination and/or unhelpful beliefs about sleep mechanisms of change in CBT-I on symptoms of depression?

Examination of rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep at baseline will allow a comparison between the mechanistic contribution of a transdiagnostic cognitive process (rumination) and disorder-specific cognitions (unhelpful beliefs about sleep). Consistent with Lovato and Gradisar (2014) and previous results in adolescents with DSWPD (Richardson & Gradisar, 2022), we hypothesised that rumination would mediate the relationship between symptoms of insomnia and depression. However, as comorbidities are manifestations of underlying transdiagnostic processes (Harvey et al., 2004; Krueger & Eaton, 2015), we did not expect that specific unhelpful beliefs about sleep would mediate the relationship between insomnia and depression given its disorder-specific nature. Based on recent findings in the adult literature (Ballesio et al., 2021) we anticipated that CBT-I would reduce unhelpful beliefs about sleep but not rumination, however, given the transdiagnostic nature of rumination, that changes in rumination would mediate the effect of CBT-I on depression to a greater extent than unhelpful beliefs about sleep. Reporting of the mediation analyses follow recommendations provided by the AGReMA Statement (Lee et al., 2021).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

This study used data from 264 adolescents who participated in the Sleep Ninja RCT (Werner-Seidler et al., 2023; ACTRN12619001462178). Participants were recruited into the study through online channels (paid, targeted social media advertisements on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter) and community pathways (schools, psychology clinics, councils). For inclusion, participants needed to be between the age of 12–16 years, report elevated insomnia symptoms (score of ≥10 on the Insomnia Severity Index [ISI]); (Bastien et al., 2001), own a smartphone (iPhone or Samsung), live in Australia, speak and read English fluently, and provide parental and personal consent. Recruitment commenced on 25 October 2019 and concluded on 6 September 2020. Participants were randomly allocated to the intervention or control group. Participant demographics and baseline insomnia and depression symptoms by group allocation is presented in Table 1.

| Intervention group (n = 131) | Active control group (n = 133) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD, range) | 14.70 (1.16, 12.05–16.92) | 14.74 (1.27, 12.02–16.97) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 40 (30.3) | 32 (24.1) |

| Female | 89 (67.4) | 100 (75.2) |

| Other | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| Born in Australia, n (%) | 122 (92.4) | 127 (95.5) |

| Previous diagnosis of depression or anxiety by a professional, n (%) | 56 (42.4) | 63 (47.4) |

| Taking medication, n (%) | 38 (28.8) | 46 (34.6) |

| Currently receiving psychological treatment for sleep or mental health problem, n (%) | 46 (34.8) | 43 (32.3) |

| Symptoms (M, SD) | ||

| Insomnia; ISI | 16.64 (4.11) | 17.03 (3.58) |

| Depression; PHQ-9 | 13.82 (5.84) | 13.68 (5.85) |

| Sleep variables (M, SD) | ||

| Rumination; RTSQ | 96.44 (24.68) | 94.01 (22.44) |

| Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep; DBAS | 33.45 (5.99) | 32.38 (5.99) |

Measures

Insomnia symptoms

The seven-item ISI was used to assess insomnia symptoms over the previous 2 weeks (Bastien et al., 2001). Items are rated from 0 (none) to 4 (very severe), producing total scores of 0–28, where scores of 8–14 indicate subthreshold insomnia and 15–28 indicate clinical insomnia. The ISI has been validated in adolescents with strong reliability (α = 0.83) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.79) (Chung et al., 2011).

Depression symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-Adolescent Version (PHQ-A) (Johnson et al., 2002) is a widely administered, nine-item questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms in the preceding 2 weeks, adapted for adolescents. It has been validated in adolescents and demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Johnson et al., 2002; Kroenke et al., 2001), including reliability (α = 0.89), test–retest reliability (r = 0.84), and good sensitivity (73%) for major depressive disorder. Items are scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), producing scores from 0–27, with 10–14 indicating moderate symptoms, 15–19 indicating moderately severe symptoms and 20 and above indicating severe depression.

Rumination

The 20-item ruminative thought style questionnaire (RTSQ; Brinker & Dozois, 2009) was selected to measure transdiagnostic, symptom-independent rumination as it has good psychometric properties in adolescents (Tanner et al., 2013). Items are scored on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all descriptive of me; 7 = describes me very well), with scores ranging from 7–140 with higher scores indicating a greater tendency to ruminate.

Unhelpful beliefs about sleep

The 10-item dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep scale for children (DBAS; Gregory et al., 2009) assesses unhelpful insomnia-related cognitions. Items are scored on a five-point scale (1 = strongly agree; 5 = strongly disagree), with scores ranging from 1–50 and higher scores indicating greater unhelpful beliefs about sleep. It has strong psychometric properties (Blunden et al., 2013).

Conditions – intervention and control

Intervention

The Sleep Ninja smartphone app is a CBT-I intervention designed with the input of adolescents (Werner-Seidler et al., 2017) and described in detail elsewhere (Werner-Seidler et al., 2019; Werner-Seidler et al., 2023). It contains six training sessions (lessons) derived from CBT-I, which are delivered via the Sleep Ninja, which acts as a sleep coach via a chatbot function. Each training session is 5–10 min in duration, covering psychoeducation, stimulus control and wind down, sleep hygiene, planning for diversions from sleep routine, sleep-focussed cognitive therapy and a programme summary and relapse prevention. Gamification principles are incorporated into the programme so that once a training session and three nights of sleep tracking have been completed users level up (gain access to the next training session) and are awarded their next “belt” until they attain their “black belt” in sleep. Additional features include a “Sleep Tips” section and “Get Help Now” section which lists crisis support lines.

Control

The control group received weekly SMS sleep tips for 6 weeks (matched to intervention period) taken directly from the educational but non-therapeutic “Sleep Tips” section of the Sleep Ninja app.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC#190139). Screening, consent, assessments, allocation to condition, and delivery of the intervention were carried out using an automated trial management system hosted by the Black Dog Institute. Young people and their parents/guardians who responded to advertisements were directed to the study website where information sheets and consent forms were available. Following parent/guardian and personal consent, participants progressed through the screening process. Eligible participants proceeded to the baseline assessment and completed the questionnaire battery containing the ISI, PHQ-A, RTSQ, and DBAS. The battery also contained additional outcomes (e.g., anxiety, wellbeing), detailed in Werner-Seidler et al. (2023). Participants were then randomised to the intervention or control condition using an automated computer-generated programme integrated into trial management software, with a 1:1 ratio. Participants allocated to the intervention group were directed via email and SMS to the App Store or Google Play to download the Sleep Ninja app onto their personal smartphone and could access the app for 6 weeks. Participants allocated to the control condition were automatically informed via email and SMS that they would be receiving weekly sleep tips and suggestions to improve their sleep by SMS, for 6 weeks.

The post-intervention assessment was administered following the 6 week intervention period, and the follow-up assessment was administered 2 months after the completion of the post-intervention assessment. Participants were reimbursed with a AUD$10 electronic gift card for completing questionnaires and sleep diaries at each assessment point (total of $30 for full study participation).

Statistical analyses

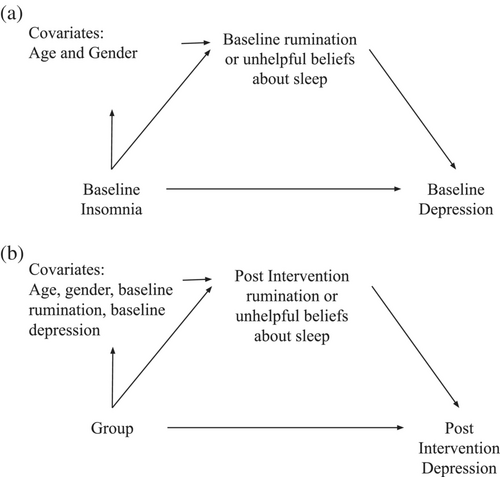

Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®), version 27. All analyses were based on the intent-to-treat sample, which included all participants in the group to which they were randomised, regardless of adherence to the intervention. The relationships between symptoms of insomnia, depression, rumination, and unhelpful beliefs about sleep were examined using Pearson's correlations on baseline data across the whole sample. To examine the extent to which the association between symptoms of insomnia and depression were mediated by rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep (Aim 1), separate linear regression mediator analyses were run on baseline data using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) for each mediator as depicted in Figure 1a. To isolate sleep onset difficulties from the broader conceptualisation of insomnia, the same analyses were conducted on baseline data using only the first item of the ISI (“difficulty falling asleep”). To demonstrate temporal precedence, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by re-running the analysis using only the control group, using sleep predictors at baseline and post-intervention depression scores as the outcome variable.

The effect of CBT-I on rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep was examined using linear mixed modelling (LMM) on the baseline and post-intervention data, with time as the within-group factor (baseline, post) and condition as the between-group factor (intervention vs. control) (Aim 2). This approach handles missing data by including all available data from each subject into the analysis and assumes missing data are missing at random. Between-groups effect sizes were calculated as the modelled standardised mean difference at post-intervention.

To determine whether rumination or unhelpful beliefs about sleep mediated the effect of CBT-I on symptoms of depression (Aim 3), both traditional between-subjects mediation analyses and within-subjects mediation analyses were conducted. The between-subject mediation analysis was used to determine whether the effect of the intervention (i.e., Sleep Ninja or SMS sleep tips) on depression symptoms is mediated by rumination or unhelpful beliefs about sleep. The within-subjects mediation analysis was included because there were substantial improvements in insomnia symptoms in both the intervention and control groups (Werner-Seidler et al., 2023). This analysis removes group as a predictor, helping to determine whether improvements in rumination contribute to improvements in depression following the use of Sleep Ninja. Following recommendations by Hayes and Rockwood (2017), between-subject analyses included covariates for baseline outcome and mediator variables to control for baseline variation in depressive symptoms, and rumination or unhelpful beliefs about sleep. The between-subjects mediation model used post-intervention rumination and depression data as depicted in Figure 1b. Separate within-subjects mediation analyses were conducted for each mediator (rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep) using the MEMORE macro (Montoya & Hayes, 2017) and included participants in the intervention group only. This approach examines whether pre- to post-intervention changes in the proposed mediator is associated with pre- to post-intervention changes in the outcome variable. As such, baseline and post-intervention data for the mediator and outcome variable are included in the analysis. Covariates were not included as these analyses focused on changes over time and it was assumed that fixed covariates (such as age) would not change over time. In both the between- and within-subject analyses, statistical significance was determined by examining 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals around indirect mediation estimates (based on 5000 bootstrap re-samples); confidence intervals that did not include zero were evidence of statistically significant mediation.

Finally, sensitivity analyses were conducted, which consisted of re-running all analyses using the PHQ-A with the sleep item removed. Since removing the sleep item from the PHQ-A did not change any results, for parsimony, only analyses with the full PHQ-A are reported.

RESULTS

Relationship between insomnia, depression, rumination, and unhelpful beliefs about sleep

There were large correlations between symptoms of insomnia and depression (r = 0.60, p < 0.001), and between symptoms of depression and rumination (r = 0.55, p < 0.001). There were moderate correlations between symptoms of insomnia and rumination (r = 0.41, p < 0.001), and between rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep (r = 0.32, p < 0.001). As age was significantly associated with symptoms of depression (r = 0.25, p < 0.001), rumination (r = 0.17, p < 0.001), and unhelpful beliefs about sleep (r = 0.20, p < 0.001), and one-way Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) found significant gender differences, with females reporting greater symptoms of insomnia (F(1, 259) = 4.97, p = 0.03), symptoms of depression (F(1, 259) = 24.68, p < 0.001), rumination (F(1, 259) = 9.69, p < 0.01) and unhelpful beliefs about sleep (F(1, 259) = 9.30, p < 0.01), age and gender were controlled for in the mediation analyses (i.e., entered as covariates). Correlations between baseline symptoms of insomnia, depression, rumination, and unhelpful beliefs about sleep across the whole sample are presented in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2 displays path coefficients, estimated indirect mediation effects, and direct and total effects of rumination and beliefs about sleep on symptoms of depression. Results indicate, when controlling for age and gender, rumination was a significant partial mediator of depression symptoms (Effect = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.12–0.27), whereas unhelpful beliefs about sleep was not. Isolating sleep onset difficulties from overall insomnia symptoms produced the same results, with only rumination a significant partial mediator (Effect = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.34–1.15) but with a larger co-efficient. The results remained unchanged when we re-ran the analysis using the control group only and the post-intervention PHQ-A scores as the outcome (Table S2, Supplementary materials). Specifically, rumination, but not unhelpful beliefs about sleep, was a significant partial mediator between overall insomnia and depression (Effect = 0.19, % CI = 0.07–0.32), and between sleep onset difficulties and depression (Effect = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.11–0.26).

| Mediator | Path coefficients | Direct effect (SE) | Total effect (SE) | Indirect effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of insomnia on mediator (SE) | Unique effect of mediator (SE) | Indirect effect (SE) | 95% CI | % of total effect | |||

| Overall insomnia | |||||||

| Rumination; RTSQ | 2.37 (0.34)* | 0.08 (0.01)* | 0.65 (0.07)* | 0.84 (0.07)* | 0.19 (0.04)* | 0.12, 0.27 | 22.40 |

| Unhelpful beliefs about sleep; DBAS | 0.28 (0.09)* | 0.09 (0.05)* | 0.81 (0.07)* | 0.84 (0.07)* | 0.03 (0.02) | −0.00, 0.07 | 3.10 |

| Difficulties with sleep onset | |||||||

| Rumination; RTSQ | 6.65 (1.70)* | 0.11 (0.01)* | 1.68 (0.35)* | 2.40 (0.39)* | 0.72 (0.21)* | 0.34, 1.15 | 30.00 |

| Unhelpful beliefs about sleep; DBAS | −0.00 (0.45) | 0.19 (0.05)* | 2.40 (0.38)* | 2.40 (0.39)* | −0.00 (0.10) | −0.20, 0.18 | 0.01 |

- Abbreviations: CI, bootstrapped confidence interval; DBAS, dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep scale for children; RTSQ, ruminative thought style questionnaire; SE, bootstrapped standard error.

- * Significant at p < 0.05.

Effect of CBT-I on rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep

Estimated marginal means and between-group effect sizes are presented in Table 3, along with the number of participants completing outcome measures at baseline and post-intervention for each group. There was greater attrition from the intervention group from baseline to post-intervention (45%) compared the active control group (30%). Adherence to Sleep Ninja was modest, with participants in the intervention condition completing on average 2.3 of the six Sleep Ninja sessions. More detail regarding adherence to the intervention is in Werner-Seidler et al. (2023). Reductions in rumination did not differ between the intervention and control groups at post-intervention indicating CBT-I had a no significant effect on rumination. In contrast, there was a significantly greater reduction in unhelpful beliefs about sleep in the intervention group relative to the control group at post-intervention, 95% CI = 0.09–3.66, d = 1.24.

| Intervention group | Active control group | Post-assessment Time × Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 132) | Post (n = 73) | Baseline (n = 133) | Post (n = 106) | t | df | p | |

| Rumination; RTSQ | 96.44 (2.05) | 89.67 (2.84) | 94.02 (2.05) | 91.76 (2.53) | 1.54 | 169.57 | 0.13 |

| Unhelpful beliefs about sleep; DBAS | 33.45 (0.52) | 30.52 (0.70) | 32.38 (0.52) | 31.32 (0.59) | 2.07 | 175.62 | 0.04* |

- Abbreviations: DBAS, dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep scale for children; RTSQ, ruminative thought style questionnaire.

- * Significant at p < 0.05.

Mediators of the effect of CBT-I on symptoms of depression

Table 4 summarises the between-subjects (CBT-I vs. control) and within-subjects estimated indirect mediation effects, direct and total effects of rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep. Results show that neither rumination nor unhelpful beliefs about sleep emerged as significant mediators. However, the within-subject mediation analysis found rumination (Effect = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.06–1.32), but not unhelpful beliefs about sleep, emerged as a significant mediator (Table 4). This indicates that baseline to post-intervention reductions in rumination were associated with baseline to post-intervention reductions in depression symptoms in the intervention group.

| Mediator | Path coefficients | Direct effect (SE) | Total effect (SE) | Indirect effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of group on mediator (SE) | Unique effect of mediator (SE) | Indirect effect (SE) | 95% CI | % of total effect | |||

| Between-subjects mediation | |||||||

| Rumination; RTSQ | 4.83 (2.91) | 0.08 (0.02)* | 1.73 (0.72)* | 2.10 (0.75)* | 0.38 (0.28) | −0.08, 0.10 | 18.10 |

| Unhelpful beliefs about sleep; DBAS | 1.34 (0.86) | 0.20 (0.07)* | 2.05 (0.79)* | 2.31 (0.80)* | 0.26 (0.21) | −0.11, 0.73 | 11.26 |

| Within-subjects mediation | |||||||

| Rumination; RTSQ | 2.83 (0.66)* | 3.40 (0.65)* | 0.56 (0.33)* | 0.06, 1.32 | 16.55 | ||

| Unhelpful beliefs about sleep; DBAS | 2.78 (0.75)* | 3.47 (0.70)* | 0.69 (0.38) | −0.28, 1.64 | 19.89 | ||

- Abbreviations: CI, bootstrapped confidence interval; DBAS, dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep scale for children; RTSQ, ruminative thought style questionnaire; SE, bootstrapped standard error.

- * Significant at p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined rumination and unhelpful beliefs about sleep as mediators of the relationship between symptoms of insomnia and depression, and as mediators of the effect of CBT-I on symptoms of depression. This is the first analysis to examine the potential of cognitive factors to mediate the link between symptoms of insomnia and depression in adolescents. Moreover, this is the first study to compare a transdiagnostic cognitive process (rumination) with a disorder-specific cognitive process (unhelpful beliefs about sleep) as mediators of reductions in depression following CBT-I. Consistent with predictions, we found that rumination, but not unhelpful beliefs about sleep, was a significant partial mediator of the relationship between symptoms of insomnia and depression at baseline, and remained a partial mediator when its temporal precedence was assured. Results were the same, if not stronger, when isolating sleep onset difficulties from overall insomnia symptoms. While our between-subject mediation analysis found neither cognitive factor mediated the effect of CBT-I on depression symptoms, findings from the within-subject mediation analysis demonstrated that reductions in depression symptoms following CBT-I can be attributed, at least partially, to reductions in rumination. These findings were robust to sensitivity analyses.

Given the transdiagnostic nature of rumination, it was expected that rumination would mediate the link between symptoms of two distinct clinical presentations, insomnia and depression. Rumination also accounted for reductions in depression following CBT-I, further demonstrating its importance as a mechanism linking insomnia and depression symptoms. Notably, CBT-I led to reduced unhelpful beliefs about sleep but not rumination. This finding is consistent with a recent review of the adult literature, which found CBT-I reduced sleep-related worry but had less impact on rumination (Ballesio et al., 2021). While well supported and influential models hypothesise an important role for worry and rumination in insomnia onset and maintenance, it remains possible that CBT-I is effective only for cognitive processes that are sleep-related (e.g., worrying and ruminating on sleep-related concerns; Harvey, 2002). The results of the current study suggest that improving CBT-I's effect on global (i.e., not disorder-specific) rumination, or repetitive negative thinking more broadly, may potentially amplify its effect on depressive symptoms.

Augmenting CBT by including components specifically targeting rumination as an underlying mechanism has been demonstrated for mixed depression and anxiety (Newby et al., 2014). Existing interventions, such as mindfulness-based CBT (MBCT; Segal et al., 2018), have also been found to reduce rumination and prevent depression relapse (de Klerk-Sluis et al., 2022; Perestelo-Perez et al., 2017). The most widely studied intervention specifically designed to target rumination is rumination focussed-CBT (RFCBT; Watkins et al., 2007) which has been shown to reduce rumination in adults and adolescents (Cook et al., 2019; Hvenegaard et al., 2020; Topper et al., 2017). While these interventions successfully reduce rumination, they also reduce disorder-specific symptoms (Perestelo-Perez et al., 2017). Adding components of these interventions that target rumination to CBT-I offers an opportunity to improve effects on depression, which could be evaluated in future studies.

Findings from the current study support Lovato and Gradisar's model that identifies rumination as mediating the relationship between sleep disturbance and the development of depression in adolescents (Gradisar et al., 2022; Lovato & Gradisar, 2014). Our finding that sleep onset difficulties as the predictor produced a greater indirect effect via rumination relative to overall insomnia further supports the aspect of the model that specifically stipulates a role for wakefulness in bed (i.e., sleep onset difficulties) promoting rumination prior to sleep. Rumination has also been found to increase at the end of the day, particularly in depressed individuals (Takano & Tanno, 2011). Notably, Sleep Ninja does not contain sleep restriction therapy, which is a critical component of CBT-I, particularly for reducing time spent awake in bed (Cain et al., 2022). This may account for our finding that CBT-I did not reduce rumination because this strategy specifically aims to reduce time awake in bed and therefore the opportunity for rumination prior to sleep. It is therefore possible that a CBT-I intervention that includes sleep restriction may be more effective at reducing rumination by addressing sleep onset difficulties.

Rumination was a partial, not full, mediator of the relationship between insomnia and depression symptoms suggesting other mediators and mechanisms of change likely exist. One potential candidate that warrants inclusion in future investigations is pre-sleep arousal. Pre-sleep arousal refers to both cognitive and physiological arousal that prevents sleep onset and exacerbates insomnia (Harvey et al., 2005). It is possible that reducing pre-sleep arousal would reduce wakefulness in bed preventing excessive rumination, thereby protecting against the development of depression symptoms.

A limitation of the rumination measure included in this study is that it did not distinguish between pre-sleep rumination and rumination occurring at any other time of the day. To distinguish between pre-sleep and daytime rumination and explore their differential role as mediators, future studies could incorporate momentary measures of rumination, such as those developed by Rosenkranz et al. (2020). Another limitation is we did not examine rumination content. This prevented comparing global and sleep-related rumination as mediators of the studied relationships, however, we are not aware of any validated measures specifically assessing sleep-related rumination rather than more global repetitive negative thinking. There was greater attrition from the intervention group compared with the control group and despite using analyses that account for missing data, it remains possible that non-random attrition may have affected the results. The control group did not match the intervention group regarding attentional demand, nor was adherence to the control condition measured. Replication of our findings is needed using an attention-matched control condition for validation. Finally, several mediation analyses were conducted on data drawn from the same time points preventing conclusions regarding causal mediation over time. To address this limitation, future studies could assess outcomes mid-treatment and use the data from these intermediary time points in the mediation models. Future studies could also use longitudinal designs and experimental manipulations of rumination to better establish rumination as a causal mediator of the relationship between insomnia and depression symptoms and include other potential mediators.

In conclusion, we found that transdiagnostic rumination, but not disorder-specific unhelpful beliefs about sleep, mediated the relationship between insomnia and depression symptoms, with preliminary evidence for causal mediation. Reductions in rumination also accounted for reductions in depression symptoms following CBT-I, but CBT-I itself did not reduce rumination. Reducing rumination alongside targeting sleep may improve existing therapeutic approaches.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sophie H. Li and Aliza Werner-Seidler conceived of the study. Sophie H. Li conducted analyses and prepared the manuscript. Brittany Corkish supported data analysis and manuscript preparation. Cele Richardson and Helen Christensen provided methodological expertise. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.