Workers' moral hazard and private insurer effort in disability insurance

Abstract

While it is well known that supplementary private Disability Insurance (DI) has the potential to increase workers' moral hazard, the extra coverage may also increase incentives for private insurers to reduce caseloads by means of prevention and reintegration activities. With unique administrative data on DI contracts of firms in the Netherlands, this paper aims to disentangle these worker and insurer responses to increased coverage. Supplementary insurance increases the insurers' incentive to lower disability risks, but in our setting it also creates an incentive for the insurers to facilitate partial work resumption of disabled workers who have earnings capacity. Using firm- and time-fixed effects models on the absence and employment rates, we find that insurer effort counteracts workers' moral hazard.

1 INTRODUCTION

Public Disability Insurance (DI) schemes are ubiquitous in developed countries, and costly. Roughly 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) is spent on public disability and sickness benefits in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries on average, and 1% of GDP in the United States in 2018 (OECD, 2024). But while public DI benefits are mandatory and provide coverage for all workers, there is also an important role for private, supplementary DI. For instance, about 35% of the workers in the United States have complementary private long-term DI (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023).1 Institutional details differ from country to country. In the Netherlands, private DI tops up statutory benefits whereas, in the United States, private DI typically contains offset clauses that reduce private benefits dollar by dollar when receiving public benefits (Autor et al., 2014). In Germany, public and private DI benefits are largely independent (Fischer et al., 2024).

A well-known concern with supplementary DI is that it may further increase workers' moral hazard. Workers may be encouraged to apply for DI, may reduce their effort to return to work, and may reduce their effort to combine employment with DI benefit receipt. A large empirical literature studies such workers' moral-hazard effects in DI, mostly using changes in workers' incentives of public DI schemes for causal inference.2 These moral-hazard concerns are also relevant when private insurance—mostly offered as group contracts to workers in firms in the United States—imposes fiscal externalities on public insurance (Chetty & Saez, 2010; Pauly, 1974). One overlooked aspect, however, is that supplementary DI also affects the incentives of private insurers. Depending on the degree of competition in insurance markets, and given their financial interest in reducing benefit payments, private insurers may become more inclined to organize work accommodations together with the insured firms, and thus provide preventive activities or offer financial rewards to workers in case of (partial) work resumption. This raises the general question whether workers or insurers are more responsive to incentives, as well as what are the specific ways in which they differ in their ability to increase the opportunity for workers to resume work. Insurers may benefit from scale advantages and have more expertise than workers do in organizing and imposing work accommodations to firms. There is no evidence so far that disentangles the impacts of these two forces.

This paper studies the causal effect of private supplementary DI contracts on benefit- and employment outcomes in the Netherlands. In our setting, supplementary contracts top up statutory Partial and Temporary (WGA) disability benefits. Disabled workers in the WGA program are deemed to have remaining earnings capacity, which is measured by the income they could earn from functions and working hours that are still feasible. The level of WGA benefits depends on the assessed “degree of disability (DoD)”, which is the difference between the preapplication wage and the earnings capacity (i.e., the earnings loss) as a percentage of the preapplication wage. Since its start in 2006, the WGA program implemented a strong reduction in benefit generosity for workers with a DoD below 80% and increased the incentives for workers to use their earnings capacity. Specifically, disability benefits of workers without sufficient earnings were no longer tied to the preapplication wage but instead to the statutory minimum wage. Particularly for disabled workers with higher preapplication wages, this led to a strong decrease in the replacement rate of DI benefits. But concurrent with this, insurers introduced private supplementary contracts that partially or fully offset the loss of insurance coverage due to the reform. Use of these “gap insurance” contracts, which are concluded as group contracts at the level of firms, has increased gradually over the years, amounting to 66% of all workers in 2021 (SZW, 2022).3

In our setting, firms purchasing supplementary insurance have already opted out of public insurance and have bought private insurance contracts to provide insurance for statutory DI benefits. In contrast to Workers' Compensation in the United States, however, firms that opt out in the Netherlands cannot self-insure. Instead, they must purchase a standardized plan from a private insurer that features mandatory benefit settings and automatic coverage for all workers. In effect, opting-out then implies that these firms are no longer subject to the financial risks inherent with experience-rated (public) DI premiums and typically pay uniform premiums instead that are based on the sector and the composition of the employed workers. Moreover, private insurers may offer specialized return-to-work policies to these firms. Private insurers cannot deny claims or increase monitoring activities, which is the responsibility of the public Employee Insurance Agency (UWV). In 2011, 37% of firms in the Netherlands had opted out, and since then percentage has remained quite stable (Hassink et al., 2015). When firms purchase supplemental coverage that tops up the statutory coverage levels, this increases the financial interest of the insurer to reduce disability risks. This particularly holds for disabled workers with high preapplication wages for whom the additional coverage from supplementary benefits is most substantial.4 Policy conditions of supplementary insurance contracts typically include increased case management both in the absence period and for WGA benefit recipients.5 Supplementary insurance also creates an incentive for insurers to facilitate employment for disabled workers, for instance by organizing work accommodations. In contrast to the case with statutory benefits only, any additional wage earnings crowd out part of the supplementary benefits. This implies a decrease in the marginal work incentive for disabled workers, and a commensurate increase in the incentives of the insurer.

We use unique administrative data from Robidus Risk Consulting, a large Dutch insurance intermediary. Our base sample is comprised of workers in firms that have opted out from public DI and therefore (already) have bought private insurance contracts for statutory DI.6 In the time period under investigation, a fraction of firms in this sample extends the coverage of WGA benefits from their private insurer with supplementary insurance beyond the statutory level. These voluntary contracts, which are most commonly used and were initiated at the start of the WGA scheme, supplement benefits up to 70% of either the lost earnings capacity (“Basic Supplementary Insurance” [BSI]), or the preapplication wages (“Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance” [CSI]). Compared with the counterfactual with statutory DI only, we expect that not only workers' moral hazard will increase due to the extra insurance, but also that private insurers will face stronger financial incentives to counteract moral hazard.

We estimate the effect of supplementary insurance on absence, benefit awards, and employment of awarded DI recipients. We employ specifications with firm- and year-fixed effects, using the switches of firms from contracts with statutory coverage only to contracts with supplementary DI. To interpret the effect of firms' contract switches on worker outcomes as causal, two assumptions must hold. First, the worker composition of firms should not change as a consequence of the switch of DI contract. We provide evidence in favor of this assumption by comparing the worker characteristics of switching firms. Second, there should be no time variant unobservables that are correlated with the firms' decision to switch and our outcomes of interest. While we cannot test the second assumption directly, we use an IV strategy that provides us with plausibly exogenous variation in firms' switching behavior. Since Robidus approaches firms for supplementary insurance periodically based on their sector, we use sectoral variation in supplementary insurance as an instrumental variable for having supplementary insurance. We find a strong first stage, and a negative but noisy second stage, which is in line with our main results. This suggests that time-varying unobservables do not play a major role in our context.

Since supplementary insurance changes the incentives for both worker and insurer, our estimates of switches on the absence and DI applications can be interpreted as the joint effect of worker and insurer behavior. Our results provide no evidence that supplementary DI leads to a higher probability of applying for DI benefits, as workers' moral hazard would predict. Rather, our evidence indicates lower application probabilities. This suggests one of two things: either the higher benefits do not cause anticipatory behavior of workers, or insurer behavior (or other policy parameters than the extra coverage) compensates for worker moral-hazard effects.

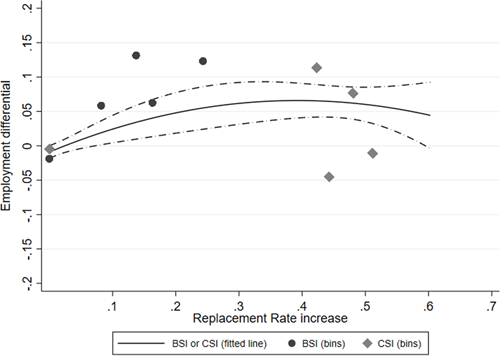

We next separate the employment effects of worker and insurer incentives, focusing on awarded DI applicants in the WGA program. For this we use the earlier-mentioned cutoff rule for the setting of statutory WGA benefits. When the DoD exceeds 80%, workers receive 70% of their old wage, but below this threshold benefits are proportional to the DoD and tied to the statutory minimum wage. As a result, the replacement rate of the benefit jumps to a markedly lower level below the 80%-cutoff. For the sample of workers with statutory benefits only, the 80%-cutoff allows us to identify and estimate employment effects to benefits. Assuming that workers cannot earn more than their assessed earnings capacity and therefore continue receiving the same level of DI benefits, employment effects due to differences in replacement rates can be interpreted as workers' moral hazard. Stated differently, it is only the worker—and not the insurer—who has a financial interest to increase wage earnings up to the level of the earnings capacity at maximum. We then find that a 1% increase in the replacement rate for workers decreases employment by 0.11 percentage points, corresponding to a Labor-Force-Non-Participation (LFNP) elasticity of 0.12. Using the switches to supplementary insurance, we can also estimate an LFNP elasticity that represents a combined worker and insurer effect. From this, we find that workers with the supplementary insurance show slightly higher employment rates than those with statutory insurance only. Combining this LFNP elasticity estimate with the estimate derived from variation in statutory benefits, this suggests that the insurer offsets the workers' moral-hazard effect.

This paper contributes to a large body of empirical studies on the impact of DI benefits on workers' moral hazard (see, e.g., recent overviews by Cabral & Dillender, 2020; Dal Bianco, 2019). This line of research has shown the following: more generous benefit conditions increase applications to a duration of disability (Autor et al., 2014; Cabral & Dillender, 2020; Gelber et al., 2017); DI receipt decreases labor supply and wage earnings (French & Song, 2014; Garcia-Mandicó et al., 2020; Maestas et al., 2013); and changes in benefit conditions affect employment and earnings of benefit recipients (Gruber, 2000; Koning & Van Sonsbeek, 2017; Kostøl & Mogstad, 2015; Marie & Castello, 2012; Weathers & Hemmeter, 2011). Zooming into the literature on employment effects that focus specifically on sick pay or sick pay mandates, we see that the US evidence so far is limited—see, for example, Pichler and Ziebarth (2020), Boots et al. (2009), and Ahn and Yelowitz (2015) for contributions.7 Our analysis confirms the general finding that more generous DI benefits decrease labor supply. As to private supplementary insurance, however, our results suggest that these effects are counteracted by increased insurer effort to exploit the remaining earnings capacity of disabled workers.

We also contribute to a smaller literature that suggests that firm and insurer incentives reduce workers' disability claims (Koning, 2016). Although our analysis does not directly focus on the firm that is incentivized, we believe that the effects of this literature are indicative of the ability of the insurer to—directly or indirectly—reduce disability caseloads and increase work resumption. Private insurers can realize such effects with the use of work bonuses, work accommodation reimbursements for firms and enhanced case management. There is evidence for both public DI schemes and Workers' Compensation schemes that experience-rated DI premiums for firms can be an effective tool for doing so (De Groot & Koning, 2016; Koning, 2009; Korkeamäki & Kyyrä, 2012; Kyyrä & Paukkeri, 2018; Tompa et al., 2012). Similar to private insurers that are financially responsible for the costs of benefits, experience-rated or self-insured firms have an incentive to counteract workers' moral hazard. In this respect, Guo and Burton (2010) are one of the few studies that link the concepts of worker and firm incentives for Workers' Compensation. They argue that benefit and frequency elasticities for Workers' Compensation benefits decreased after 1990, when large deductibles increased the incentives of firms. Using 25 years of data on Workers' Compensation, Bronchetti and McInerney (2012) arrive at similar results.

Finally, our results add to the broader discussion on not only the desirability of choice in insurance contracts (Cabral et al., 2022; Cabral & Cullen, 2019; Hendren et al., 2021), but also the welfare effects of combined public and private insurance (Chetty & Saez, 2010; Pauly, 1974). While insurance choice in DI acknowledges variations in individual valuations, private supplementary insurance may also induce or enlarge adverse selection and moral-hazard problems. The literature points to fiscal externality effects in the United States and Canada (Autor et al., 2014; Stepner, 2019). In our setting, however, private insurers bear the financial risk inherent in combining statutory benefits and supplementary insurance. As a result, fiscal externalities are absent.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional setting, followed by a description of data in Section 3. Section 4 outlines our research strategy, and Section 5 discusses the impact of supplementary insurance on the probability of workers of recovering during the absence period and applications made to DI. Section 6 discusses the effect on employment outcomes for awarded DI applications. Section 7 concludes.

2 INSTITUTIONAL SETTING

2.1 DI in the Netherlands

The flowchart in Figure 1 shows that the statutory sick leave program and DI in the Netherlands are merged programs. DI applications of workers follow automatically after an absence period of 2 years. This contrasts to, for example, the United States, where mandatory sick leave programs—typically referred to as Temporary Disability Insurance benefits or “medical leave”—are limited and where workers need to initiate DI applications (Burkhauser et al., 2016; Pichler & Ziebarth, 2020). In the Netherlands, firms are obliged to continue 100% of the wages in the first year and 70% in the second year of sick leave.8 The so-called Gatekeeper Protocol prescribes the reintegration activities that need to be followed by firms in the 2-year absence period to become admissible for DI applications (Godard et al., 2022; Koning & Lindeboom, 2015). The public Employee Insurance Agency (UWV) assesses DI applications; their medical doctors determine the presence of impairments and labor experts assess their consequences for the earnings capacity.

Figure 1 also shows that there is no separate Workers' Compensation program for occupational disability risks in the Netherlands, but a comprehensive categorical DI transfer program (WIA) that provides public statutory insurance against loss of income due to work-related and nonwork-related conditions—see, for example, Burkhauser et al. (2016) for a detailed international comparison. DI benefit conditions are determined by the assessed loss of earnings capacity as a fraction of the preapplication wage—that is, the DoD—together with the assessed permanence of impairments. When the assessed DoD is below 35%, the worker does not receive any DI benefits. At the other extreme, workers with a DoD of 100% and medical conditions that are deemed permanent receive full and permanent benefits (IVA) replacing 75% of the old wage. In between, workers with a DoD exceeding 35% but below 100% and without current earnings capacity but temporary impairments, are entitled to the Partial and Temporary DI program (WGA). Workers with degrees of disability equal to or exceeding 80% receive WGA benefits equal to 70% of their preapplication wage. For workers with a smaller loss of earnings capacity, however, benefits are proportional to the DoD, and the level of benefits is tied to the minimum wage (see Section 3.2). Since its inception in 2006, the idea of the WGA scheme was to enhance work incentives for disabled workers with earnings capacity. The new scheme, however, also laid the groundwork for the rise of private supplementary contracts that compensate for the loss of coverage.

The Partial and Temporary (WGA) program aims to encourage not only workers to use their remaining earnings capacity, but also firms. Similar to Workers' Compensation in the United States, the premiums of the WGA scheme are experience-rated for firms (Koning, 2016). As explained earlier, about 37% of firms had opted out from public insurance to buy private insurance contracts that provide coverage against the risk of WGA premiums (Hassink et al., 2015). Opting-out insurance contracts typically have uniform premiums, which implies that the risks inherent in WGA benefit costs are transferred to the private insurer. As part of these opting-out contracts, insurers also provide preventative and reintegration services in both the period of the absence and during DI receipt, and send out caseworkers that help firms with the requirements that need to be met to file a potential DI application.

2.2 Private supplementary insurance: Benefit conditions

With data in this paper that come from private insurers, our analyses are conducted on workers in firms that have opted out at some point in time. Private insurers have thus already taken over the statutory WGA benefit payments of firms. In addition, the same insurers offer firm-level contracts that supplement disability benefits of their workers. These supplementary contracts take the public, statutory disability benefit level as given, and top up benefit coverage. Supplementary insurance is concluded as “group contracts” at the level of firms. Similar to private Long-Term Disability policies in the United States, the extra coverage can be considered as “fringe benefits” (Autor et al., 2014; Pichler & Ziebarth, 2020). It is estimated that 66% of all workers in the Netherlands had supplementary WGA contracts in 2021 (SZW, 2022).

We focus on two supplementary insurance contracts for DI that are most common in the Netherlands: BSI and CSI. Both contract types are referred to as “gap insurance,” since they partly or fully offset the loss of statutory insurance coverage due to the switch to the WGA program in 2006.9 With this in mind, BSI and CSI contracts have become the standard since 2006, leaving little room to customize contracts in other dimensions. BSI and CSI contracts go together with intensified case management—predominantly in the absence period, but also for disabled workers with WGA benefits—and financial bonuses for disabled workers to use their earnings capacity. These bonuses are the same for BSI and CSI, and are relevant for workers with a DoD below 80%, constituting 5%–10% of the preapplication earnings. For a more detailed picture of the contract conditions, Table A1 in Appendix A provides a standard CSI contract for workers in firms within the Dutch care sector, and shows variations of contracts that Robidus offers.

BSI and CSI offset (part of) the work incentives for disabled workers with a DoD below 80%. For these workers, statutory WGA benefits are tied to preapplication wages only if the worker earns at least 50% of their assessed earnings capacity. If not, DI benefits are instead tied to the minimum wage. For instance, a disabled worker with a DoD of 50% should have earnings that exceed 25% of the preapplication wage to have WGA benefits tied to the preapplication wage instead of to the minimum wage.

2.3 Worker and insurer incentives

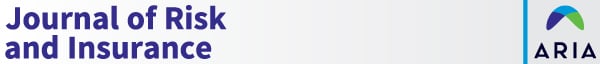

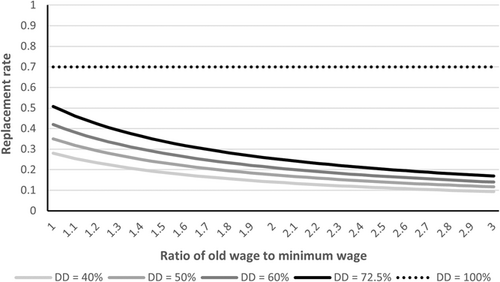

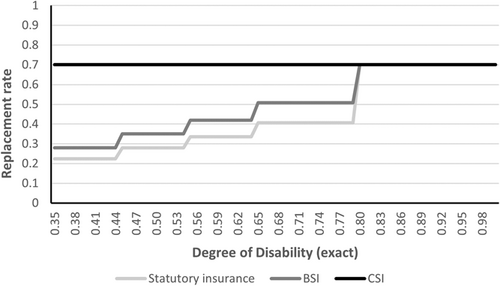

To analyze the effects of supplementary insurance, we calculate its effects on replacement rates that express the income from DI benefits and without wage earnings as a fraction of preapplication wages.13 The idea is that worker incentives decrease with increases in replacement rates, but are accompanied by an equal increase in the financial interest of the insurer.

Figure 2 illustrates how BSI and CSI affect the incentives of workers and insurers to use worker earnings capacity. Given that earnings exceeding the assessed earnings capacity are rare,14 this setting well represents the employment decision of disabled workers. We consider two cases of a worker with a DoD of 50%: one in which the old wage equals the minimum wage (Panel a), and one in which it equals 150% of the minimum wage (Panel b).15 The black bars in Figure 2 indicate the replacement rates when the worker is unemployed; and the dark and light gray bars indicate the extra income (as a fraction of the old wage) for the worker and the insurers' benefit savings when the worker fully uses their earnings potential, respectively.

Panel (a) considers the case where the old wage of the worker equals the statutory minimum wage. Since statutory benefits are also tied to the minimum wage, BSI does not provide any additional coverage and the replacement rate equals 35% (70% 50%) of the old wage in both cases. CSI supplements the benefit up to 70% of the old wage. This means that 70% of the earnings potential (i.e., 35% of the old wage) goes to the insurer, and 30% to the worker (i.e., 15% of the old wage). In Panel (b) the old wage equals 150% of the statutory minimum wage. Since the benefit with BSI is tied to the old wage instead of the minimum wage, the replacement rate increases from 23% to 35%. The private insurer then experiences an equal increase in the financial interest of (partial) work resumption. This financial interest is substantially higher with supplementary insurance from CSI, amounting to about 47% of the old wage of the worker.

The two examples show that with statutory insurance only disabled workers with a DoD below 80%—and not private insurers—have a strong financial interest to increase earnings up to the level of their assessed earnings capacity. As a percentage of the old wage, the extra income—amounting to 50% from extra earnings and 12% from the wage subsidy in the example in Panel (b)—is fully received by the worker. With BSI and CSI, however, both workers and insurers have an interest in using their earnings potential. In these cases, the insurer receives the full wage subsidy if the worker meets the 50%-earnings threshold. For CSI contracts the financial interest of the insurers is larger, since they also receive 35% of the old wage (i.e., 70% 50%) and the workers' share of the extra earnings decreases to the same extent. This can be interpreted as an implicit tax rate (of 70%) on wage earnings.

3 DATA AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

3.1 Data setup

We use unique administrative data from Robidus Risk Consulting, a large insurance intermediary in the Netherlands conducting return-to-work services and providing supplementary insurance to contracted firms for sick-listed and disabled workers. All contracted firms in our sample receive private insurance against the financial risks inherent with WGA benefits, and a fraction of firms also has supplementary DI from BSI or from CSI. Recall that all firms in our sample have already opted out to private insurance. Accordingly, we will compare firms that also buy BSI or CSI at some point in time to those firms that have not done this, and assess the effect of the extra coverage from the same insurer.16 The firms that contract with Robidus are relatively large. Most firms are in the education, health, and, to a lesser extent, construction sectors. As the descriptive statistics will show later on, the over-representation of these sectors is mirrored by a high share of women with preapplication earnings that are relatively low.17

We combine three data sources from Robidus. First, we have firm-level data containing contracts between 2006 and 2019. These data contain the contract type: that is, only statutory insurance, BSI, or CSI with the start and end dates of each contract. From talks with experts we infer that there is case management for all workers with BSI and CSI in the absence period, as compared with very low take-up rates without supplementary insurance. Unfortunately, however, we do not have data on the services inherent in more intensive case management. Insurer effort is therefore unobserved in our analyses, and inferences made on the importance of this follow from model assumptions that will be explained in Section 4. Although individual workers may opt out from BSI or CSI contracts, this occurs only very rarely. Experts from Robidus indicated that less than 1% of the workers concerned opt-out.18 Our second data source contains long-term absent workers in contracted firms with an absence spell of at least 10 months. This corresponds with the maximum amount of elapsed time to meet a licensed doctor. The third data set includes information on every worker that applied for DI after 2 years of absence from work. These data also contain award decisions and the type and level of benefits of awarded applicants. For awardees with WGA benefits, we also observe wage earnings at the moment of and after the application date.

Our data contain 2080 firms, of which 90 (4.3%) have supplementary insurance for the entire period, 299 (14.4%) switch to BSI or CSI at least once during the sample period, and the remaining 1691 firms have no supplementary insurance over the entire period.19 We observe 101,408 long-term sick-listed workers (i.e., on average 49 workers per firm) of which 15,981 (15.8%) are covered by supplementary DI. We do not see any difference in the number of workers that are long-term absent around the years of firm switches towards supplementary insurance. Our supplementary DI rate is higher than the average in the Netherlands in 2014, but lower than in 2022 (Cuelenaere et al., 2014; SZW, 2022).

In our context, we argue that selection of individuals with higher disability risks is unlikely. One major reason is that contracts are set at the level of firms or sectors. To the extent that firm-specific conditions, worker characteristics or trends drive long-term absence and disability inflow rates, Robidus also takes the initiative to contract new firms—mostly clustered in specific sectors—and to upgrade contracts to include supplementary insurance. For this, it uses its own network of HR managers and mostly contacts firms that already have statutory insurance for which Robidus is financially responsible. Since Robidus sets BSI and CSI premiums that are based on past disability risks of firms and current long-term absence rates that may add to future DI inflow rates, the room for adverse selection by firms appears limited. Robidus is most likely better informed about the true disability risks than their clients are. We return to this issue when discussing descriptives of firms and the effect of switches to supplementary insurance.

3.2 Descriptive analysis

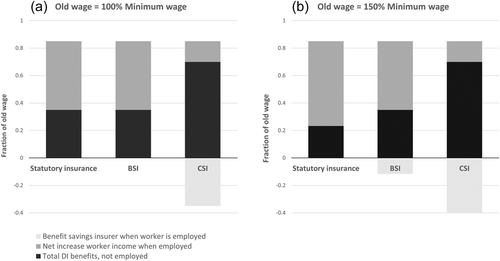

Figure 3 shows the number of long-term sick-listed workers per cohort in our sample under the different types of insurance. Worker inflow is increasing over time, which stems from an increase in the number of contracted firms, but not from increases in firm size. The fraction of workers with supplementary insurance has also increased, from nearly 2% of the cohort of 2011 to 26% of the most recent cohort of 2018. A joint F test on whether worker-observable characteristics (i.e., gender, age, and tenure) explain firm switching is rejected (p = 0.824).

Table 1 presents statistics of the full sample of sick-listed workers and the sub-sample of (36,537) workers who eventually applied for DI. In terms of awards, our sample covers about 10% of the full Dutch population of benefit recipients. Absence spells are not observed for all DI applications in our sample, since Robidus took over caseloads from other intermediaries. As a result, the number of applicant observations exceeds the number of absence spells ending at 24 months.20 The sample of applicants has noticeably and significantly less often opted for supplementary insurance from BSI and CSI. This largely reflects the fact that switches to supplementary insurance are observed earlier in the absence data than in the (subsequent) application data that are registered after the 2-year absence period. Workers are on average 46.6 years old in both samples, and applicants have relatively more tenure. 71% of the workers in our sample are female. This stems from the large fraction of firms in the health and education sector. Finally, about 23% of applications are rejected, whereas 18.8% are awarded benefits for whom BSI and CSI are relevant.

| Full sample | DI applicants | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) (%) | 5.8 | 4.1 |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) (%) | 10.0 | 6.1 |

| Age (years) | 46.6 | 46.6 |

| (11.1) | (10.5) | |

| Tenure (years) | 12.9 | 15.5 |

| (13.4) | (16.2) | |

| Percentage of females (%) | 71.0 | 72.3 |

| Application outcomes (%) | ||

| — Rejected applications (%) | 23.4 | |

| — WGA benefits, degree of disability 80% (%) | 18.8 | |

| — WGA benefits, degree of disability 80% (%) | 37.1 | |

| — Permanent DI benefits (IVA) (%) | 20.8 | |

| Observations | 101,408 | 36,537 |

- Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- Abbreviations: DI, Disability Insurance; IVA, permanent DI benefits.

- Data source: Robidus workers' long-term sickness data.

Appendix Table D1 compares workers in firms and years with only statutory insurance to workers with BSI and CSI. For awarded applicants, the table does not include workers with permanent DI benefits (IVA) for which there is no experience rating (see Figure 1). For sick-listed workers, the table shows that workers with supplementary insurance are older, are more often females, and have significantly less tenure than those with statutory insurance alone.21 These differences are also reflected in the sample of awarded applicants. Preapplication wages are generally low—reflecting the fact that some female workers have part-time jobs22—and slightly higher for awardees with supplementary insurance. A small fraction of workers in our sample with part-time jobs have wage earnings below the full-time minimum wage. In these cases, benefits are also tied to preapplication earnings and are below the level of social assistance benefits (equal to about 70% of the minimum wage).

Since preapplication wages are relatively low, the impact of insurance caps on benefits is limited. Replacement rates are therefore equal to 70% for almost all disabled workers with a DoD equal to or exceeding 80%, and also for disabled workers below the 80% cutoff with CSI. Average replacement rates for awarded applicants with degrees of disability below 80% and with statutory insurance equal 22.2%, as compared with 36.4% for those with BSI and 69.7% for those with CSI. Table D4, which compares the “true” replacement rates of workers (in bold) with fictitious replacement rates under different contract types, shows that the differences on average replacement rates are entirely driven by contract types and not by the selection of preapplication wages. Finally, Table D1 shows that awardees with supplementary insurance have higher employment rates and higher wage earnings than those with statutory insurance alone. The employment difference amounts to about 10 percentage points for workers with degrees of disability below 80%, as compared to an (absolute) employment rate with statutory insurance equal to 34.3%. In line with expectations, these differentials are much smaller for the sample of workers with degrees of disability exceeding 80%.

4 ESTIMATION STRATEGY

Our estimation strategy is comprised of two stages. We first model and estimate the effect of supplementary insurance from BSI and CSI on all outcome variables. This includes outcomes based on the information on absence spells before DI application and the employment information for the sample of awarded DI applicants. The effects of supplementary insurance can then be interpreted as the joint worker and insurer effect of increased coverage. We next extend our model with replacement rate effects and disentangle worker moral hazard from insurer effects. Given that employment outcomes and replacement rates are observed and relevant only for awarded applicants, we limit this part of our analysis to awarded applicants and focus on the employment outcomes of this sample.

4.1 The basic model

We first model the joint effect of supplementary insurance coverage. With firms switching from providing statutory insurance to BSI and CSI at some point in time, we use a model with firm- and time-fixed effects.23 We compare changes in outcomes of sick-listed and disabled workers of firms that have switched to supplementary insurance contracts to changes in outcomes of workers with firms that have not (yet) switched. In order for our model to reflect the causal impact of supplementary insurance contracts on absences, disability, and work, we need two assumptions to hold: (i) the employee composition of firms should not change as a consequence of the switch of DI contract, and (ii) there should be no time-varying unobservables that are correlated with the decision to switch insurance contracts and our outcomes of interest. To test these assumptions, we will compare the number and composition of workers who become absent around the years of a switch, and use variation in contract switching (i.e., sector-specific shocks) that are plausibly exogenous to test the robustness of our findings.

4.2 Separating worker and insurer effects

Similar to Equation (8), the log replacement rate consists of three components. As a baseline, represents the log replacement rate for statutory DI benefits of disabled workers with a DoD below 80%. This component is determined by the DoD and the level of old wages. Since both of these variables directly affect employment outcomes, we will flexibly control for all possible outcomes of these variables in all employment models.

is an interaction term representing the increase in the log replacement rate just above the 80% DoD threshold for workers without BSI and CSI. The higher the old wage, the stronger the implications of the 80% threshold of the DoD. Given that we control for the DoD and old wages, the identification and estimation of log replacement rate effects based on come from interacted degrees of disability and old wages. The effect of on employment can be fully interpreted as workers' moral hazard due to increases in statutory coverage. Assuming that workers cannot earn more than their earnings capacity, any changes in earnings will not crowd out statutory benefits and do not increase the financial interest of the insurer to stimulate employment.

represents the replacement rate increase stemming from the extra nonstatutory insurance coverage from BSI and CSI for disabled workers with a DoD below 80%. The interpretation of replacement rate effects is different than for : for the insurer, changes in wage earnings of these disabled workers imply benefit savings. Part of the gains of using the workers' earnings capacity therefore shifts from the worker to the insurer, rendering a joint worker and insurer effect.

Equation (11) controls for by extending with polynomials of the log of old wages, which is denoted as matrix . consists of polynomial functions of the (exact) degrees of disability with parameters that vary across calendar years. represents workers' moral-hazard effects, and represents the joint effect of supplementary insurance due to worker moral hazard and insurer effort.26

5 RESULTS: THE ABSENCE PERIOD AND APPLICATION OUTCOMES

5.1 Graphical evidence

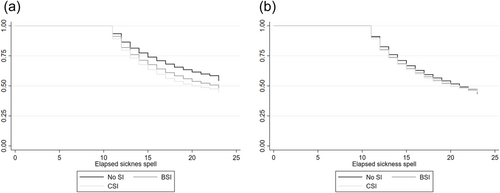

We first study the effect of supplementary insurance on worker recovery rates in the absence period. Although the insurance coverage is equal for workers with and without supplementary insurance before DI application, workers and insurers may anticipate higher worker benefits after 2 years. Workers may be less likely to recover, whereas private insurers may target their activities towards workers with higher expected coverage. For graphical evidence on which effect may be most relevant, Panel (a) of Figure C1 in the appendix shows the Kaplan–Meier survival rates for workers with only statutory insurance, BSI and CSI, measured for long-term sick-listed workers.27 The figure shows that workers with supplementary insurance recover faster.

In line with our empirical approach, we also zoom into the smaller sample of firms that switch to BSI or CSI over time; see Panel (b) of Figure C1. Specifically, we compare the absence spells of workers who report absent in the years around the contract switch, that is, who report absent at least 12 months before the contract switch and at most 12 months after the switch.28 This plausibly renders the groups of workers that we compare more similar. Panel (b) shows that the difference in absence spells then virtually disappears. Workers with supplementary insurance still seem to recover faster, but the difference appears statistically insignificant.

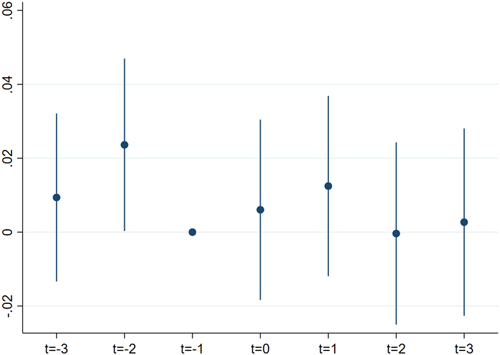

Finally, we compare the likelihood of DI application for workers who start their spell just before the firm's switch towards supplementary insurance (and therefore fall under the old insurance policy) and for workers who start their spell just after. For a time window of 3 years before and after switches to supplementary insurance (either BSI or CSI), we compute the difference between the fraction of absences of at least 24 months (and its standard error) and the fraction of absences of at least 24 months 1 year before the switch. This is often referred to as an event-time model. Our model differs in one important way. In the standard model the event is at the firm level (a change in DI contract), while our analysis is at the individual level. Consequently, we mostly have multiple observations in the same time period of one firm. Figure 4 shows the estimates and standard errors, suggesting there is no significant impact of a firm switch towards supplementary insurance. Note that even without control variables our estimates are already quite precise. In addition, if we pool all of the post-switch estimates we get a coefficient of 0.005 (with confidence interval: −0.015, 0.025), suggesting that we can reject effect sizes of 2.5 percentage points or less.

5.2 Estimation results

Table 2 shows the impact of BSI and CSI on the probability of a worker remaining absent for at least 2 years. Column (i) shows that supplementary insurance from both BSI and CSI increases the probability of recovering by about two percentage points, as compared to an average recovery rate after 24 months of 22.1%. With firm-fixed effects (in column (ii)), the effect of CSI becomes borderline significant and equals 3.4 percentage points. Note that these results are comparable—and with smaller standard errors—to those with Cox duration models for elapsed absence spells.29 To assess the robustness of our findings, column (iii) shows similar effects for a specification that includes placebo effects for the 2 years preceding any switches to BSI and CSI. The effects become even smaller and insignificant when we add sector-specific calendar-time effects (with 49 sectors in total).30 This leads us to conclude there are no strong or dominant worker moral-hazard effects in the absence period preceding DI applications.

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | (iv) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | −0.022** | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| (0.011) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.012) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | −0.019** | −0.034* | −0.033* | −0.018 |

| (0.008) | (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.017) | |

| Demographic and tenure controlsa | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed effects | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Placebo testb | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Sector-specific time effectsc | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| Firms | 2063 | 2063 | 2063 | 2063 |

| Firm-year observations | 98,624 | 98,624 | 98,624 | 98,624 |

| R2 (within) | 0.065 | 0.065 | 0.160 | |

| R2 (total) | 0.071 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.142 |

- Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses. The dependent variable is a binary that equals 1 if a worker is absent at least 24 months, and zero if not.

- a Controls include the workers' age, gender, and tenure at the firm.

- b For the placebo test we include dummy values for firms that were in the 2 years preceding switches to BSI and CSI, respectively. The estimates of the BSI and CSI placebos are insignificant, −0.018 (p = 0.34) and −0.003 (p = 0.855).

- c We add the firm's sector and interact it with time dummies to capture sector-level specific events that may cause changes in workers probabilities of absence.

- * and ** indicate significance at 10% and 5% levels, respectively.

- Data sources: Robidus workers' long-term absence and firm contract data.

It is possible that firms adjust other aspects of their personnel policies than insurance coverage when switching towards supplementary DI contracts. For instance, more generous DI policies may prove more attractive for workers who are absent more frequently, which may then change the composition of newly hired workers. Differences in absence may therefore be wrongly assigned to the impact of the policy, while the true impact would come from compositional changes in hiring and firing of personnel. To study whether this is an issue in our data, we estimate the probability that a firm switches towards BSI or CSI using the composition of the pool of absent workers. We estimate Logit models where we regress the average characteristics of the firm (in terms of age, gender, and tenure) on the probability of a firm switch. The results in Table D2 in the appendix show that there is no significant relation between these firm characteristics and the switch towards supplementary insurance. As a second robustness exercise we add yearly firm-averaged characteristics of workers—that is, age, gender, and tenure—to the regressions in Table D3 in the appendix. The results also show that the impact of BSI and CSI on the probability of remaining absent for at least 24 months is virtually unchanged.

Another concern may be that firms still anticipate a change in the probability that workers report absent, and therefore decide to adjust DI contracts. This would imply that our estimates are biased by selection effects. We therefore analyze the timing of a contract switch in two ways. First, viewing the contract switch as an event, we use an “event-time design”; we study whether workers who become absent just before the switch differ in terms of recovery and work behavior from those workers who report absent just after the switch. With selection effects, one would expect positive coefficients—that is, more long-term sick-listed workers—directly following the contract change towards supplementary DI. Second, we analyze whether firms that switch contracts early have different worker outcomes than firms that switch later. Tables D5 and D6 in Appendix D show that there is little evidence of treatment heterogeneity over time. The event-time estimates in Table D5 are similar to those in Figure 5, but now based on a regression including workers' age, gender, and tenure at the firm as control variables. Again we see no significant impact of switching towards supplementary insurance. The coefficients of event-times “0” and “3” show marginally significant results, but a joint test on the post-event dummies suggests insignificance. The estimates in Table D6 for each insurance contract are also of similar size, suggesting that the exact year of the switch is not relevant.

We argued earlier that switches to supplementary insurance are often concentrated in sectors. This follows from the fact that Robidus not only approaches firms periodically, but also concentrates on particular sectors. We thus also conduct a robustness test that exploits this sectoral variation as an instrumental variable. Specifically, we use the fraction of other firms within the same sector (we have 49 sectors in the data) as an instrument for the choice of insurance. This presupposes that a given firm's decision to purchase supplementary insurance is correlated with the decision of other firms within the sector, but not with long-term absences of workers directly. For efficiency reasons, we merge CSI and BSI into one instrument. Table D7 in Appendix D reports a strong first-stage coefficient, but an imprecise second-stage coefficient. If anything, the estimation qualitatively confirms our earlier finding of supplementary insurance leading to increased absence.

Given that we find marginally higher recovery rates with CSI, we finally analyze whether this effect concerns workers with less severe health conditions who are denied benefits at a later stage. To shed light on this, Table 3 shows estimates for the probability that applicants end up with rejected applications, WGA benefits (below or above the 80% cutoff) and permanent and full benefits (IVA). We also consider a linear model which ranks the four statuses. Our results generally do not show significant differences across contract types, except for the higher share of applicants awarded IVA benefits with CSI. For the full sample of absent workers, this increase compensates for the (proportional) decline in applications for permanent benefits. The inflow into this scheme is thus less responsive to the extra coverage.

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | (iv) | (v) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejected | WGA | WGA | Permanent | Categories | |

| Application outcomes | applicants | DoD 80% | DoD 80% | DI (IVA) | 1–4 |

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | −0.011 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.020 |

| (0.021) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.022) | (0.045) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | −0.017 | −0.005 | −0.011 | 0.033** | 0.072* |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.016) | (0.041) | |

| Demographic controls, tenurea | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 35,516 | 35,516 | 35,516 | 35,516 | 35,516 |

| R2 (within) | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.040 | 0.129 | 0.063 |

| R2 (overall) | 0.030 | 0.014 | 0.043 | 0.134 | 0.065 |

- Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- Abbreviations: DI, Disability Insurance; DoD, degree of disability.

- a Controls include the workers' age, gender, and tenure at the firm.

- * and ** indicate significance at 10% and 5% levels, respectively. The mean values of the categories are 0.22, 0.19, 0.38, and 0.21, respectively.

- Data sources: Robidus workers' long-term absence and firm contract data.

6 RESULTS: EMPLOYMENT OF AWARDED DI APPLICANTS

6.1 Graphical evidence

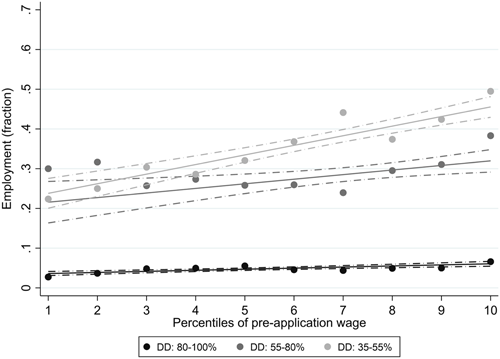

We next turn to the sample of awarded DI applicants for whom we observe their degrees of disability, old wages and replacement rates after application. To eyeball the presence of interacted effects of preapplication wages and degrees of disability, Figure 5 presents employment rates for percentiles of preapplication wages for the sample of firms with statutory insurance alone. As argued earlier, these data may be indicative of workers' moral hazard. The employment averages shown in “bins” are stratified by three DoD categories: 35%–55%, 55%–80%, and 80%–100%. The figure also shows linear fitted lines for the three samples. Consistent with workers' moral hazard, the slope of employment probabilities with respect to the old wages is less steep for low degrees of disability and almost absent for workers with a DoD equal to or exceeding 80%. This suggests an interacted effect of old wages and degrees of disability, alongside the isolated impact of these variables. Since replacement rates are lower for disabled workers with degrees of disability below 80% and with higher old wages, it is possible that higher statutory replacement rates induce worker moral hazard.

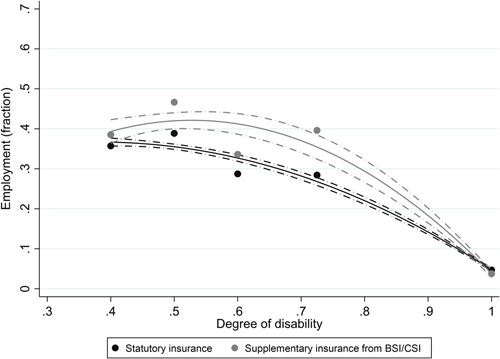

We also graphically explore the effect of supplementary insurance on employment. Figure 6 compares the employment rates of awarded workers with different degrees of disability according to insurance status.31 Since we have a limited number of BSI observations for each DoD class, we pool the observations with BSI and CSI. Most strikingly, we then see that disabled workers with degrees of disability of more than 45% (and below 80%) show higher employment rates when they receive supplementary insurance from BSI or CSI. Contrasting this to Figure 5, this suggests a limited role for workers' moral hazard and/or a strong mitigating role for insurance policy parameters (and insurer activities) other than insurance coverage.

6.2 Estimation results

Table 4 shows the estimation results of the effect of log replacement rates and supplementary insurance on the employment of awarded DI applicants. For all model variants we use three polynomials for log preapplication wages and four polynomials for degrees of disability for each year in our sample.32 As a reference point, column (i) shows the estimates of BSI and CSI contracts without replacement rates, as in Equation (9). Recall that these dummies capture the joint effect of worker moral hazard and insurer effort. For the full population of workers that switched to these two contract forms, employment rates do not differ significantly with respect to the control group of individuals that did not switch or had not switched yet.

| Model specification | (i) | (ii) | (iii) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | 0.018 | 0.020 | 0.013 |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.013) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | 0.023** | 0.037*** | 0.016 |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.012) | |

| Log replacement rate | −0.058*** | ||

| (0.009) | |||

| – “Worker moral-hazard” effect () | −0.107*** | ||

| (0.011) | |||

| – “Joint worker and insurer” effect from BSI/CSI () | 0.028* | ||

| (0.015) | |||

| Degree of disability: 4 polynomials 15 years | YES | YES | YES |

| Log preapplication wages: 3 polynomials | YES | YES | YES |

| Age, gender, and tenure (12 dummies) | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| Labor-Force-Non-Participation Elasticity: Worker | 0.066 | 0.122 | |

| Labor-Force-Non-Participation Elasticity: insurer | −0.154 | ||

| Worker/firm observations | 27,495 | 27,495 | 27,495 |

| Firm observations | 1612 | 1612 | 1612 |

| R2 (overall) | 0.1742 | 0.1755 | 0.1778 |

| R2 (within) | 0.1671 | 0.1683 | 0.1702 |

- Notes: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- ** and *** indicate significance at 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Data sources: Robidus Disability Insurance application data and firm contract data. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to one with positive wage earnings, and zero otherwise.

Models (ii) and (iii) of Table 4 add (log) replacement rates to the model. Model (ii) assumes equal effects of changes in replacement rates due to statutory and supplementary DI benefits, which implies that there are no effects of additional insurer effort and that only worker moral hazard may be relevant. This yields a significant elasticity estimate of −0.058, which corresponds to an LFNP elasticity of 0.066. Since the average log replacement rate is substantially higher for CSI, it is not surprising to see that the effect estimate of CSI increases compared to model (i). This compensates for the effect running through the (higher) log replacement rates.33

Model (iii) corresponds to Equation (11) with separate log replacement rate effects. The first effect of the log replacement rates now represents only worker moral-hazard effects. Recall that this effect is identified from the cutoff-effect of the 80% threshold of the DoD. The implied LFNP elasticity of this effect equals 0.122. This estimate is close to that of Koning and Van Sonsbeek (2017), who exploit differences in the timing of changes in WGA benefits to identify response effects. It is also close to LFNP estimates obtained by Kostøl and Mogstad (2015) for Norway. The coefficient of the second replacement rate—from supplementary coverage ()—is positive and borderline significant. The difference between this coefficient and the first one equals the insurer effect, which equals 0.135 and corresponds to an LFNP elasticity induced by the insurer of −0.154. Concurrent with this, the “constant” effects of extra coverage indicated by the BSI and CSI dummies become statistically insignificant. This suggests that private insurers focus on—and succeed in—reducing worker moral hazard among disabled workers with degrees of disability below 80% (for whom there is extra insurance coverage), but not for workers above the 80%-threshold (for whom replacement rates are unaffected by supplementary insurance).

To examine the robustness of the findings for the employment model, we used various other specifications, different samples and estimation methods, all of which confirm our results that indicate the joint existence of worker and insurer responses to extra coverage. Most notably, we used inverse sampling weighting to obtain samples that are comparable to the sample of long-term sick-listed workers, we conducted Placebo analyses on (unaffected) WGA recipients with a DoD exceeding 80%, and we used more flexible specifications that zoom into the 80% cutoff for the DoD. The results of these analyses, appearing in Table E1, are discussed in detail in Appendix E.

6.3 Interpreting insurer effort

Given the effect of extra coverage on employment, one may be tempted to conclude that the response of private insurers—such as increased work accommodations or work bonuses—is proportional to the extra insurance coverage of workers. The scope for proportional actions by the insurer is, however, limited. Recall that contracts are set at the level of firms and are not fine-tuned for individual workers. Policy parameters other than coverage—such as the presence of work bonuses—are the same for BSI and CSI contracts, and apply to all disabled workers. Preventative activities are relevant for all long-term sick-listed workers in the absence period, as well as for those who do not yet know the outcome of any future application decisions. This calls for a model specification with a common effect that applies to all disabled workers with supplementary insurance and below the 80% threshold for the DoD, irrespective of the size of the workers' increase of the replacement rate.

Table 5 shows the estimation results for Equation (12) for employment. For ease of comparison, column (i) repeats the results from the baseline specification of Equation (11). The results in columns (ii) and (iii) show substantial and positive additional employment effects that are relevant for those disabled workers who have supplementary insurance and a DoD below 80%. This effect of almost 10 percentage points suggests that private insurers do not target specific workers with the highest additional coverage. More strikingly, we find evidence that the marginal effect of replacement rates on employment for workers with supplementary insurance is the same as for those with only statutory benefits. So, to the extent that moral hazard is a marginal response to higher benefits, its impact is equally relevant if workers have supplementary insurance. These results indicate the presence of certain compensating actions by the insurer that apply to all workers with extra coverage, rather than targeted actions.

| Model specification | (i) | (ii) | (iii) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.004 |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.021) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | 0.016 | 0.025* | 0.022 |

| (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.017) | |

| Supplementary Insurance DoD 80% () | 0.097*** | 0.094*** | |

| (0.019) | (0.023) | ||

| Log replacement rate () | −0.089*** | −0.089*** | |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | ||

| — “Worker moral-hazard” effect () | −0.107*** | ||

| (0.011) | |||

| — “Joint worker and insurer” effect () | 0.028* | ||

| (0.015) | |||

| Log replacement rate supplementary insurance () | −0.008 | ||

| (0.039) | |||

| Degree of disability: 4 polynomials 15 years | YES | YES | YES |

| Log preapplication wages: 3 polynomials | YES | YES | YES |

| Age, gender, and tenure (12 dummies) | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| Worker/firm observations | 27,495 | 27,495 | 27,495 |

| Firm observations | 1612 | 1612 | 1612 |

| R2 (overall) | 0.1778 | 0.1760 | 0.1760 |

| R2 (within) | 0.1702 | 0.1692 | 0.1692 |

- Notes: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- Abbreviations: DI, Disability Insurance; DoD, degree of disability.

- a The results in column (i) follow from the estimation of Equation (11), whereas columns (ii) and (iii) show results from (variants of) Equation (12).

- *** and * indicate significance at 1% and 10%.

- Data sources: Robidus DI application data and firm contract data. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to one with positive wage earnings, and zero otherwise.

7 CONCLUSION

A well-known concern with social insurance programs is that they may induce or increase risk selection and moral-hazard problems. The extensive evidence indicating the existence of moral-hazard effects for statutory public DI could therefore be used to build more of a case against supplementary insurance. Such concerns may be exacerbated by the fiscal externalities that private DI may have on public DI (Chetty & Saez, 2010; Pauly, 1974). But this argument overlooks the fact that private insurers have an interest in developing more effective prevention and work resumption activities.

This paper analyzes the effects of private supplementary DI on workers' disability risks and the employment of disabled workers who have remaining earnings capacity. We study workers in a sample of firms that have opted out to buy private insurance to offset the financial risks inherent with experience-rated, statutory DI premiums. “Treated” workers in this sample are those employed in firms that also purchase supplemental DI coverage that tops up the statutory DI coverage levels, whereas workers in the control group are in firms with no supplementary insurance (as yet). Using models with firm- and year-fixed effects that exploit switches of firms to supplementary insurance contracts, we first estimate the effect of the extra coverage on the disability risk of long-term sick-listed workers. Since the extra coverage increases the benefits paid by the insurer, these estimates can be interpreted as the joint effect of worker and insurer behavior. For the sample of awarded DI applicants, we next derive and estimate replacement rate effects on the employment probability. Using exogenous variation in statutory replacement rates, we estimate incentive effects that can be interpreted as worker moral hazard. As long as workers cannot earn more than their assesses earnings capacity, their statutory benefits do not change with increased earnings. For the remaining variation that stems from supplementary insurance, however, increased earnings crowd out (supplementary) benefits. We thus obtain the joint effect of greater moral hazard among workers and greater effort expended by the insurer to reduce benefit costs.

We conclude that both worker moral hazard and insurer incentives are empirically important. In the absence period that precedes DI applications, workers with supplementary insurance are not less likely to recover. This holds both for contracts with “basic” supplementary insurance (BSI) and the more generous “comprehensive” supplementary insurance (CSI). We find that insurer incentives—aimed at reducing future claims with higher benefits—seem to counteract the effect of workers' moral hazard. For the sample of workers awarded DI benefits, we next estimate the separate effects of worker and insurer incentives on employment. From our results, the implied LFNP elasticity is 0.122. For switches to supplementary insurance, however, the joint effect of increased workers' moral hazard and increased insurer effort is statistically insignificant. This suggests that the insurer incentives—stemming from more generous payments to disabled workers—compensate for workers' moral hazard. Additional analyses, together with insights from the strategies pursued by the insurer, suggest that these compensating actions—such as intensified case management and work bonuses—are not confined to only those workers with the highest increases in coverage.

While there is a rich literature studying the effects of worker moral hazard on worker outcomes, little attention has been paid to incentive effects of extra coverage on the insurer. Compared with workers, insurers may have an advantage in arranging or imposing work accommodations at the workplace. According to our estimates, the insurers' ability to have workers resume work during disability is at least as strong as the workers' ability to do so—and with equal financial incentives. These findings are relevant for any scheme in which workers have temporary or partial disability—including paid leave in the United States—and in which private insurers can play a leading role in organizing case management and work accommodations. In this respect, one should bear in mind that private insurance contracts may include more policy parameters than increased coverage alone. Most notably, both of the supplementary insurance contracts we studied include financial work bonuses, a feature which calls for analyses that take a broader perspective than solely on insurance coverage.

As a final note, our results do not necessarily inform us about which incentive structure is optimal from a welfare perspective. Welfare analysis requires us to incorporate the fact that the insurer gets the worker back to (partial) employment, with the reality that this is accompanied with administrative costs and opportunity costs of workers employed at the insurer. While interesting, such an analysis falls outside the scope of this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for useful comments of seminar participants at VATT in Helsinki, the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, the Essen Health Conference, the KVS new paper sessions in The Hague, the Dutch economists' Day of 2022 in The Hague, Groningen University, and the IRDES-Dauphine Workshop on Applied Health Economics and Policy Evaluation in Paris (2022). Robidus is gratefully acknowledged for giving access to their microdata.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors herewith state to have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to research described in this paper. The authors use confidential administrative data owned by Robidus. To get access to the data, interested researchers should contact Robidus; the authors are willing to assist in doing so.

APPENDIX A: EXAMPLE OF A CSI CONTRACT

BSI and CSI contracts that are offered by private insurers can be set at the level of individual (large) firms or as part of collective agreements in specific sectors. The table below provides insight into the main elements of a collective CSI contract for the Dutch care sector, as offered by the largest private insurer in the Netherlands; see NN (2023) for the full contract. In this table, our main interest lies in the broad benefit conditions and the preventative and reintegration activities to which sick-listed and disabled workers are entitled (Table A1).

| Section | Relevant contract ingredients |

|---|---|

| (1) Insurance context | – Explanation of statutory schemes and insured population |

| – Starting date of contract | |

| – Required information of insured workers (earnings, age, etc.) | |

| (2) Coverage | – General explanation of benefit calculation and specific examples |

| – Work bonus of 10% of old wage if 50% of earnings capacity is used | |

| – Benefit indexation: based on inflation and/or collective labor agreements | |

| – Benefit caps | |

| – Reasons for ending benefits: decease, retirement, full work resumption | |

| (3) Exclusion conditions | – Molestation, risky behaviors, and other conditions for exclusion |

| (4) Reintegration | – Absence reporting after 42 weeks |

| – Firm should inform the insurer about reintegration activities during the absence | |

| – Reintegration obligations of sick-listed workers (sanction otherwise) | |

| – Reintegration specialists of insurers for sick-listed workers and workers with Disability Insurance (DI) | |

| – Reintegration specialists may make an appeal regarding DI award decisions | |

| – Reimbursement of reintegration activities | |

| (5) Premium settings | – Insured wage sum, uniform premium percentage |

| – Reasons for premium changes (e.g., due to new legislation) | |

| (6) Firm changes | – Premium consequences of, for example, new judicial status |

| (7–10) Other | – Length of contract, stopping conditions |

| – Compliance with financial and privacy rules |

-

Work bonuses: These vary between 5% and 10% of the wage before disability if more than 50% of assessed earnings capacity is used.

-

Benefit indexation: This is based on either collective labor agreements, it is indexed to the minimum wage, or is a fixed index (of 2% per year).

-

Expiration date: This equals the statutory retirement age or statutory retirement age that is capped at 68 or 70 years of age.34

-

The premium varies between 0.510% and 0.621% of the total wage sum of the insured workers. Premiums increase most strongly with respect to the degree of indexation.

APPENDIX B: IDENTIFICATION OF WORKER AND INSURER EFFECTS

Since these estimates vary with respect to and , we can identify , , and . Note that a large share of our sample consists of workers with degrees of disability equal to or exceeding 80%. Supplementary insurance does not increase the level of benefits for this group, which therefore (largely) identifies the “constant” effects, and . The sample identifies effects that are proportional to the benefit increase () from the employment outcomes of disabled workers with a DoD below 80%.

The above equation shows that the difference in the replacement rate between disabled workers above and below the 80% threshold for the DoD is proportional not only to the DoD itself, but also to the ratio of the preapplication wage to the minimum wage. The latter effect entails an interaction effect of preapplication wages and the DoD that we use for the identification of . And since the associated change in DI benefits does not change the incentive for the insurer to increase work resumption, can be interpreted as worker moral-hazard effects.

APPENDIX C: ADDITIONAL FIGURES

APPENDIX D: ADDITIONAL TABLES

See Tables D1–D8.

| Sick-listed workers | Awarded DI applicantsa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statutory | BSIb | CSIc | Statutory | BSIb | CSIc | |

| Age | 46.5 | 47.0 | 47.2 | 45.7 | 46.0 | 46.3 |

| (11.0) | (11.4) | (11.1) | (10.3) | (11.2) | (10.9) | |

| [0.031] | [0.045] | [0.019] | [0.040] | |||

| Tenure | 13.4 | 7.9 | 11.3 | 17.5 | 9.2 | 10.3 |

| (13.9) | (10.3) | (10.4) | (17.7) | (13.5) | (10.2) | |

| [−0.318] | [−0.210] | [−0.373] | [−0.352] | |||

| Females (fraction) | 0.705 | 0.800 | 0.792 | 0.707 | 0.774 | 0.816 |

| (0.456) | (0.400) | (0.406) | (0.455) | (0.418) | (0.387) | |

| [0.157] | [0.143] | [0.141] | [0.186] | |||

| WGA benefits, degree of disability 80% (fraction) | 0.301 | 0.274 | 0.306 | |||

| (0.455) | (0.418) | (0.387) | ||||

| [−0.042] | [0.008] | |||||

| Preapplication wage (euros per month) | 2196 | 2279 | 2431 | |||

| (1044) | (1076) | (1078) | ||||

| [0.055] | [0.157] | |||||

| Replacement rate | 0.555 | 0.607 | 0.698 | |||

| (0.224) | (0.156) | (0.019) | ||||

| [0.190] | [0.636] | |||||

| – Degree of disability 80% | 0.222 | 0.364 | 0.697 | |||

| (0.080) | (0.080) | (0.021) | ||||

| [1.255] | [5.743] | |||||

| – Degree of disability 80% | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.698 | |||

| (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.018) | ||||

| [0.005] | [−0.048] | |||||

| Employment at application | 0.146 | 0.153 | 0.175 | |||

| (0.354) | (0.360) | (0.380) | ||||

| [0.014] | [0.056] | |||||

| – Degree of disability 80% | 0.343 | 0.442 | 0.391 | |||

| (0.475) | (0.498) | (0.488) | ||||

| [0.144] | [0.070] | |||||

| – Degree of disability 80% | 0.062 | 0.044 | 0.081 | |||

| (0.240) | (0.205) | (0.272) | ||||

| [−0.057] | [0.053] | |||||

| Wage at application (euros per month) | 217 | 254 | 282 | |||

| (620) | (669) | (719) | ||||

| [0.040] | [0.068] | |||||

| – Degree of disability 80% | 515 | 729 | 626 | |||

| (840) | (944) | (945) | ||||

| [0.169] | [0.088] | |||||

| – Degree of disability 80% | 89 | 74 | 130 | |||

| (437) | (404) | (527) | ||||

| [−0.025] | [0.060] | |||||

| Observations | 85,427 | 5888 | 10,093 | 24,940 | 1138 | 1760 |

- Notes: Standard errors are shown in parentheses. Normalized differences with statutory benefits as reference are shown in brackets (Imbens & Wooldridge, 2009).

- Abbreviations: DI, Disability Insurance.

- a We exclude awards with permanent benefits (IVA).

- b BSI, Basic Supplementary Insurance.

- c CSI, Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance.

- Data sources: Robidus workers' long-term absence data, DI application data and firm contract data.

| (i) | (ii) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean of worker age in firm | 0.007 | −0.010 |

| (0.032) | (0.022) | |

| Fraction of workers' gender in firm | 0.672 | −0.126 |

| (0.661) | (0.473) | |

| Man of worker tenure in firm | −0.016 | −0.015 |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | |

| Year effects | YES | YES |

| Sector-specific time effects | NO | YES |

| Firms | 2063 | 2063 |

| F test on firm-level mean age, gender, and tenure | p = 0.611 | p = 0.752 |

- Note: The dependent variable equals zero if the firm has no supplementary insurance and equals one if the firm has either BSI or CSI. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- Abbreviations: BSI, Basic Supplementary Insurance; CSI, Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance.

- *, **, and *** indicate significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

- Data sources: Robidus workers' long-term absence data, DI application data, and firm contract data.

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | (iv) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | −0.023** | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.011 |

| (0.010) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.013) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | −0.020** | −0.034* | −0.033* | 0.013 |

| (0.008) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.015) | |

| Demographic and tenure controlsa | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm averages of worker demographicsb | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed effects | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Placebo testc | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Sector-specific time effectsd | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| Firms | 2063 | 2063 | 2063 | 2063 |

| Firm-year observations | 98,624 | 98,624 | 98,624 | 98,624 |

| R2 (within) | 0.065 | 0.065 | 0.136 | |

| R2 (total) | 0.071 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.108 |

- Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- a Controls include the workers' age, gender, and tenure at the firm.

- b Worker demographics include age, gender, and tenure.

- c For the placebo test we include a dummy value equal to one for firms that in the 2 years preceding the start of BSI and CSI, respectively. The estimates of the BSI and CSI placebos are insignificant, −0.018 (p = 0.34) and −0.003 (p = 0.855), respectively.

- d We add the firm's sector and interact it with time dummies to capture sector-specific events that may cause changes in workers' probabilities of absence.

- * and ** indicate significance at 10% and 5% levels, respectively.

- Data sources: Worker long-term absence data and firm contract data.

| Samples of awardees with | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fictitious replacement rates | Statutory insurance | BSI | CSI |

| Statutory insurance only | 0.222 | 0.222 | 0.223 |

| (0.080) | (0.074) | (0.079) | |

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | 0.373 | 0.364 | 0.364 |

| (0.082) | (0.081) | (0.082) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | 0.699 | 0.700 | 0.700 |

| (0.011) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

- Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses. Replacement rates shown in bold represent averages based on the “true” sample of workers for whom the specific insurance type applies.

- Data sources: Worker Disability Insurance application data and firm contract data.

| Event-time around switch | Estimates |

|---|---|

| −0.019 | |

| (0.012) | |

| −0.003 | |

| (0.012) | |

| (baseline) | |

| −0.022a, a | |

| (0.013) | |

| −0.016 | |

| (0.013) | |

| −0.015 | |

| (0.013) | |

| 0.025* | |

| (0.013) | |

| Observations | 14,975 |

- Notes: The event-time = 0 refers to the year of the switch towards supplementary insurance, either BSI or CSI. This regression includes the workers' age, gender, and tenure at the firm as control variables. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- Abbreviations: BSI, Basic Supplementary Insurance; CSI, Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance.

- * indicates significance at 10%.

- Data sources: Worker long-term absence data and firm contract data.

| Treatment effect | |

|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | |

| 2006–2013 | −0.020 |

| (0.029) | |

| 2014–2016 | 0.042 |

| (0.030) | |

| 2017–2019 | 0.034a, a |

| (0.014) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | |

| 2006–2013 | −0.044 |

| (0.033) | |

| 2014–2016 | −0.037a, a |

| (0.019) | |

| 2017–2019 | 0.004 |

| (0.020) | |

| Observations | 98,624 |

- Notes: Each variable is a dummy that equals one if the firm has switched towards BSI/CSI in this time period. This regression includes the worker age, gender, and tenure at the firm as control variables. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- * and ** indicate significance at 10% and 5% levels, respectively.

- Data sources: Worker long-term absence data and firm contract data.

| Supplementary insurance | |

|---|---|

| First stage: sector average of supplementary insurance | 0.552a, a |

| (0.124) | |

| Second stage: supplementary insurance | −0.382a, a |

| (0.141) | |

| Observations | 98,624 |

- Notes: We estimate a linear two-stage least-squares (TSLS) model. In the first stage we use the sector average (excluding the firm itself) of supplementary insurance as an instrument for the insurance status of the firm. In the second stage we estimate the impact of supplementary insurance on the probability that a worker remains absent for at least 24 months. This regression includes the worker's age, gender, and tenure at the firm as control variables, and includes firm-fixed effects. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- *** indicates significance at 1% level.

- Data sources: Worker long-term absence data and firm contract data.

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Supplementary Insurance (BSI) | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| (0.014) | (0.011) | (0.012) | |

| Comprehensive Supplementary Insurance (CSI) | 0.012 | 0.024a, a | 0.013 |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.012) | |

| Log replacement rate | −0.030a, a | ||

| (0.008) | |||

| – “Worker effect” | −0.044a, a | ||

| (0.010) | |||

| – “Worker and Insurer effect”: | 0.007 | ||

| (0.012) | |||

| Degree of disability: 4 polynomials 15 years | YES | YES | YES |

| Log preapplication wages: 3 polynomials | YES | YES | YES |

| Age, gender, and tenure (12 dummies) | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| Individual-firm observations | 20,845 | 20,845 | 20,845 |

| Firm observations | 1471 | 1471 | 1471 |

| R2 (overall) | 0.1026 | 0.1031 | 0.1037 |

| R2 (within) | 0.0905 | 0.0907 | 0.0915 |

- Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

- * and *** indicate significance at 10%, and 1% levels, respectively.

- Data sources: Worker DI application data of Robidus and firm contract data.