Performed and missed nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals: Conceptual considerations and psychometric evaluation of the German MISSCARE questionnaire

Funding information

This research, as part of the monitoring programme, was funded in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation (CRSII3_132786/1), the Käthe-Zingg-Schwichtenberg-Fonds, the Gottfried und Julia Bangerter-Rhyner-Stiftung, the Olga Mayenfisch Stiftung, the Swiss Nurses Association, the Stiftung Pflegewissenschaft Schweiz and another Foundation that does not want to be mentioned with its name.

[Correction added on Jan 28th 2021, after first online publication: Peer review history statement has been added.]

Abstract

Aim

To have at hand a reliable and valid questionnaire to assess performed and missed nursing care in a Swiss acute care context.

Background

Regular monitoring of performed and missed nursing care is crucial for nurse leaders to make evidence-based decisions. As foundation, we developed a conceptual definition. Based on this, we decided to translate and adapt the MISSCARE.

Method

In this methodological study, our newly developed German MISSCARE and previously used BERNCA-R were tested in a pilot study using a quantitative crossover design in a sample of 1,030 nurses and midwives in three Swiss acute care hospitals. Data were analysed descriptively, then using exploratory factor analysis and Rasch modelling.

Results

We obtained preliminary evidence that the German MISSCARE is sufficiently reliable and valid to measure performed and missed nursing care in our context but would benefit from structural adjustments. In contrast, the BERNCA-R proved insufficiently reliable for our purposes and context.

Conclusion

Our conceptual definition was essential for the development of the German MISSCARE. Our results support the decision to use this questionnaire.

Implication for nursing management

The adapted German MISSCARE will allow both monitoring of performed and missed nursing care over time and benchmarking of hospitals.

1 INTRODUCTION

Regular monitoring of nursing care is crucial for nurse and health leaders and politicians since missed nursing care affects health care systems globally (Jones, Hamilton, & Murry, 2015; Mandal, Seethalakshmi, & Rajendrababu, 2019), leading to reduced care quality and negative nursing-sensitive patient outcomes (Lucero, Lake, & Aiken, 2010; Schubert, Clarke, Aiken, & De Geest, 2012; Schubert, Clarke, Glass, Schaffert-Witvliet, & De Geest, 2009; Spirig et al., 2014). Further, due to shortages in the nursing workforce and system changes, it has increased over the last decade (Aiken, Clarke, & Sloane, 2001; Kalisch & Xie, 2014).

Inconsistent conceptualization and terminology concerning missed nursing care impede inter-study comparisons. The expression of unfinished nursing care was proposed by Jones et al. (2015) as an umbrella term for underuse in nursing covering different overlapping approaches. A vast majority (89%) of the published literature is based upon the three following approaches (Jones et al., 2015): (a) nursing care tasks left undone due to lack of time (Aiken et al., 2001); (b) implicitly rationed care, that is ‘the withholding of or failure to carry out necessary nursing measures for patients due to a lack of nursing resources (staffing, skill mix, time)’ (Schubert, Glass, Clarke, Schaffert-Witvliet, & De Geest, 2007); and (c) missed nursing care, that is ‘any aspect of required patient care that is omitted (partly or entirely) or delayed’ (Kalisch, Landstrom, & Hinshaw, 2009). Numerous articles focus on these approaches, but few distinguish clearly between them (Jones et al., 2015; Palese et al., 2019). Yet, attempts for international collaboration are underway to develop standard terminology (Jones, Hamilton, Carryer, Sportsman, & Gemeinhardt, June 2014; Jones, Willis, Amorim-Lopes, & Drach-Zahavy, 2019; Zeleníková et al., 2019). Astonishingly, the reviewed literature focuses conceptually mainly on unfinished nursing care and does only implicitly include performed care. Moreover, the concept of nursing care activities itself is insufficiently described.

As a nurse-sensitive performance indicator, the measurement and monitoring of performed and missed nursing care supply crucial information for nurse leaders concerning change and intervention targeting evidence-based decision-making and, ultimately, patient care quality (Kontio, Lundgren-laine, Kontio, Korvenranta, & Salanterä, 2013; Lowe & Baker, 1997; Spirig et al., 2014; VanFosson, Jones, & Yoder, 2016). Despite attempts to conceptualize, define, operationalize and measure the phenomenon, no gold standard yet exists (Palese et al., 2019).

2 BACKGROUND

In 2011, our research group initiated a long-term multiphase multicentre research programme to monitor nursing service context factors in five Swiss acute care hospitals (Spirig et al., 2014). One studied factor was nursing performance, measured via the 32-item BERNCA-R questionnaire (Schubert et al., 2013; Uchmanowicz et al., 2019). For the 2011 and 2015 phases’ data sets, our unit-level analyses indicated that within-group agreement was not sufficient with respect to the individual scores of participants at unit level, it was not significantly higher than the between-group agreement: that is, the questionnaire could not identify inter-unit differences. Alongside the fact that, within our professional context, implicit rationing represents only one aspect of unfinished nursing care (Jones et al., 2015), this meant the BERNCA-R was not suitable to monitor the latent construct nursing care activities. Considering the problems noted above and knowledge deficits regarding how Swiss acute care hospital nurses deal with performed and missed nursing care, it was necessary both to develop a definition of nursing care activities for our setting and to evaluate the questionnaires before proceeding.

2.1 Conceptual definition of nursing care activities

Professional nursing care is about recognizing individual care needs based on patients’ and their relatives’ expressed needs and nurses’ professional assessment. Based on professional judgement and decision-making with regard to the desired outcomes, these care needs result in nursing care requirements, which are the basis for the definition and planning of direct and indirect patient-related nursing care activities. Those may be supplemented by unplanned activities and prescriptions of other health care professionals. With the timely appropriate provision of these necessary care activities by the nursing team members, care is performed, the nursing care requirements can be covered and the desired outcomes can be achieved. Timely appropriate entails that the necessary care is performed at a time at which the safety and health-related well-being of the patient and his or her relatives’ is not impaired and the achievement of desired outcomes is not jeopardized.

If, for any reason, necessary care activities are omitted, left incomplete or performed at a time that is not appropriate, they are categorized as missed.

2.2 Selection of the measuring instrument

Unfinished nursing care has been measured predominantly via three ‘parent instruments’, based on the mentioned approaches (Jones et al., 2015): (a) the Task Undone Survey (Aiken et al., 2001); (b) the BERNCA questionnaire (Schubert et al., 2007); and (c) the MISSCARE questionnaire (Kalisch & Williams, 2009). To our knowledge, so far performed nursing care in the context of nursing performance has been measured mainly implicitly on the assumption that activities that were not missed were performed (Dubois, D’Amour, Pomey, Girard, & Brault, 2013). Based on our conceptual definition, we concluded that the most useful of the three ‘parent instruments’ was the American MISSCARE Part A (hereafter referred to as MISSCARE). In addition, the conceptual background, development and spread of this instrument were reasons for the decision. It asks nurses, midwives and nursing assistants to rate on a 5-point response scale how frequently (‘always missed’ to ‘never missed’) they or their unit's staff missed any of 24 listed nursing activities. As repeated psychometric testing of it has indicated high acceptability, reliability and validity (Kalisch, 2016), we translated and culturally adapted it to German. Then, we conducted a pilot study using it and the previously used BERNCA-R to compare them and to have a decision base for subsequent data collection.

3 AIMS

The overall aim was to have at hand a reliable and valid questionnaire to assess performed and missed nursing care in a Swiss acute care context. Therefore, this pilot study had two aims: (a) to assess the reliability, validity and applicability of the German-language MISSCARE and BERNCA-R questionnaires; and (b) to get indications where either could be improved. Based on our findings, we intended to choose one for subsequent data collection.

4 METHODS

4.1 Design

This is a methodological study designed to further develop and evaluate the German MISSCARE and compare it with the BERNCA-R. For the pilot study, a quantitative crossover design was applied. Data collection phases lasted two weeks each, with a four-week washout period between. Participants were randomized into two groups: one completed the BERNCA-R in Phase 1 and the MISSCARE in Phase 2; and the other, vice versa. It was also possible to participate in only one phase.

4.2 Sample and setting

We conducted the pilot study in one tertiary and two Swiss university acute care hospitals, purposively chosen from the participating hospitals in the multicentre research programme. In two hospitals, we choose 21 units and included all nurses and midwifes working there. In the third hospital, 536 participants from all units were randomly invited. That led to a purposive sample of 1,030 nurses and midwives (515 randomly assigned per crossover group) from various departments. Nurse executives provided the names and email or postal addresses of the registered nurses and midwives. Requirements for inclusion were a Swiss nursing diploma in nursing or midwifery or equivalent foreign qualification, direct involvement in nursing care and informed consent.

4.3 Instruments

While the BERNCA-R was available and no adaptions were necessary, we conducted a 7-step best-practice process of translation and adaptation for the MISSCARE (Jones, Lee, Phillips, Zhang, & Jaceldo, 2001; Wild et al., 2005): (a) preparation; (b) forward translation; (c) reconciliation; (d) back translation; (e) harmonization; (f) expert review; and (g) this pilot study.

(a) The preparation included the literature review, the conceptual work and the resulting selection of the MISSCARE questionnaire. (b) After obtaining the first authors’ consent, two native German-speaking PhD-prepared nurse scientists with good knowledge of the English language translated the MISSCARE questionnaire from US English to German. (c) A master- and a PhD-prepared nurse scientist who also have good knowledge of the English language integrated the two translated versions. (d) Two native English speakers—one with a nursing background and one working as professional translator—back-translated the integrated version independently. (e) The master- and the PhD-prepared nurse scientist compared the two translations with the original version. No substantial discrepancies were found. (f) An expert panel of five master-prepared clinical nurse specialists, three experienced PhD-prepared nurse scientists and a statistician was established to evaluate face validity. The experts were provided with the original and the translated questionnaire, the conceptual background and the working definition, and gave written feedback on all contents of the questionnaire and on possible cultural adaptations. The master- and PhD-prepared nurse scientist again integrated the responses and developed a culturally adapted version.

We made four adaptations to the German MISSCARE: (a) we complemented the introduction with our working definition; (b) to reduce recall bias, we added a recall period of seven working days to the research question; (c) to focus explicitly on performed care, we adjusted the original 5-point response scale (‘nearly always performed’ value = 1; to ‘nearly always missed’ value = 5) and added a ‘activity not necessary’ (value = 1) option to prevent missing values or to force wrong answers. Since activities that are not necessary are not considered to have been missed, we valued it the same as ‘nearly always performed’ and; (d) to take cultural differences and conceptual inconsistencies into account, we defined registered nurses and midwives as the target group and reworded and adapted several items.

The 32-item BERNCA-R questionnaire (extended from the 20-item original BERNCA) was authored in German (Schubert et al., 2013). Using a 5-point response scale, it asks respondents to rate how often they were unable to carry out each of 32 listed nursing activities over the previous seven working days. The original BERNCA has been translated and adapted for various languages and cultures (American version: PIRNCA), and adapted for nursing home use (Jones, 2014; Zúñiga et al., 2016). Psychometric testing by the primary author has confirmed its validity, internally consistency and homogeneity (Schubert et al., 2007). The psychometric properties of the German BERNCA-R had not yet been reported.

4.4 Data collection

Invitations to participate, study details and login information for the online survey, were provided via either email or paper mail. Informed consent was obtained, participation was voluntary, and anonymity was guaranteed. In Phase 1, half of the participants were asked to complete the MISSCARE and the other half the BERNCA-R. For Phase 2, a second invitation was sent and the respective other questionnaire was provided. In addition, respondents’ socio-demographic and professional variables were recorded. A free-text item on both the MISSCARE and the BERNCA-R gathered qualitative responses asking: ‘Do you have any feedback on the comprehensibility of the text (question, items, response scale) or on the applicability of this questionnaire (procedure and effort to complete)?’

4.5 Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied using percentages and sum scores (MISSCARE possible range: 25–125, with higher scores indicating more missed activities; response categories ‘activity not necessary’ and ‘nearly always performed’ were combined; only fully completed questionnaires were included for analysis). We tested the two questionnaires’ psychometric properties via exploratory factor analysis (principal axis analysis, varimax rotation) and Rasch modelling. A Rasch analysis provides a detailed analysis of many aspects of a scale, including fit of items and persons, item bias, internal consistency, dimensionality and targeting (Hagquist, Bruce, & Gustavsson, 2009; Van Alphen, Halfens, Hasman, & Imbos, 1994). However, Rasch models assume locally independent items and lack of differential item functioning (DIF). In case of local dependency (LD) or DIF, extra terms to model these deviations from a Rasch model were included. This extension is known as the graphical loglinear Rasch model (GLLRM) (Kreiner & Christensen, 2007). Statistical analyses used SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017), the R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2018) and DIGRAM 3.66 (Kreiner & Nielsen, 2013).

To assess construct validity, on the same response scale used for the MISSCARE questionnaire, we asked clinical nurse specialists in one hospital for subjective overall assessments of performed and missed nursing care on their units. If this was impossible, they were asked to compare two units regarding the extent of missed nursing activities. A high degree of agreement between their unit-specific estimates and the corresponding mean sum score of the questionnaire would indicate good convergent validity. For discriminant validity, we compared the assumed differences between two units of a department with the mean sum score of the questionnaire (DeVellis, 2003).

The qualitative responses were analysed according to the framework analysis by Ritchie and Spencer (2002). In the first stage of familiarization, the data material was viewed. Second, the index categories, given by the question, were identified. Third, the data material was indexed using the NVivo 12 Pro software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018). Fourth, the contents of the individual categories per questionnaire were analysed and related or contradictory statements were explored. Finally, the findings were interpreted and summarized narratively.

4.6 Ethical considerations

The study followed the principals of good clinical practice and was approved by the governmental ethics committees (BASEC Nr. Req-2019–00392) (International Council for Harmonisation, 2016). Participation was voluntary, informed consent obtained and confidentiality assured.

5 RESULTS

5.1 The German MISSCARE

In Phase 1 and Phase 2, 169 (32.8%) and 121 (23.5%) respondents, respectively, completed the MISSCARE, resulting in 290 response sets (total response rate: 28.2%). Table 1 summarizes respondents’ socio-demographic and professional variables and response rate per hospital.

| MISSCARE (n (%)) | BERNCA-R (n (%)) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 290 (100%) | 288 (100%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 270 (93.1%) | 262 (91.0%) |

| Male | 19 (6.6%) | 24 (8.3%) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Age category | ||

| Up to 20 years of age | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| 21–30 years of age | 110 (37.9%) | 104 (36.1%) |

| 31–40 years of age | 79 (27.2%) | 83 (28.8%) |

| 41–50 years of age | 44 (15.2%) | 45 (15.6%) |

| 51–60 years of age | 49 (16.9%) | 50 (17.4%) |

| Over 60 years of age | 7 (2.4%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Percentage of full-time employment | ||

| Up to 20% | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 30% | 8 (2.8%) | 15 (5.2%) |

| 40% | 18 (6.2%) | 18 (6.3%) |

| 50% | 18 (6.2%) | 16 (5.6%) |

| 60% | 15 (5.2%) | 13 (4.5%) |

| 70% | 15 (5.2%) | 14 (4.9%) |

| 80% | 46 (15.9%) | 49 (17.0%) |

| 90% | 50 (17.2%) | 58 (20.1%) |

| 100% | 117 (40.3%) | 103 (35.8%) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Years of employment | ||

| Up to 2.0 years | 92 (31.7%) | 82 (28.5%) |

| 2.1–5.0 years | 67 (23.1%) | 68 (23.6%) |

| 5.1–10.0 years | 42 (14.5%) | 45 (15.6%) |

| 10.1–20.0 years | 48 (16.6%) | 55 (19.1%) |

| 20.1– 30.0 years | 28 (9.7%) | 31 (10.8%) |

| 30.1–40.0 years | 12 (4.1%) | 5 (1.7%) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Response rate per hospital | ||

| Hospital 1 (n = 536) | 110 (20.5%) | 113 (21.1%) |

| Hospital 2 (n = 220) | 95 (43.2%) | 92 (41.8%) |

| Hospital 3 (n = 274) | 85 (31.0%) | 83 (30.3%) |

Of the 290 participants, 274 (94%) answered all items (total missing values: 96 (1.32%)). The mean sum score of the fully completed questionnaires was 41.8 (range: 25–82). Table 2 presents the distributions of all responses.

| Item no. | Item of the German MISSCARE Survey | Missing values | Activity not necessary (value = 1) | Nearly always performed (value = 1) | Frequently performed (value = 2) | Partly-partly (value = 3) | Frequently missed (value = 4) | Nearly always missed (value = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mc01 | Ambulation as planed or ordered | 3 (1.0%) | 18 (6.2%) | 127 (43.8%) | 85 (29.3%) | 45 (15.5%) | 10 (3.4%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| mc02 | Turning patient as planed or ordered | 5 (1.7%) | 27 (9.3%) | 126 (43.4%) | 87 (30.0%) | 37 (12.8%) | 7 (2.4%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| mc03 | Feeding patient when the food is still warm | 7 (2.4%) | 87 (30.0%) | 102 (35.2%) | 47 (16.2%) | 36 (12.4%) | 8 (2.8%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| mc04 | Setting up meals for patient who feeds themselves | 5 (1.7%) | 53 (18.3%) | 143 (49.3%) | 54 (18.6%) | 29 (10.0%) | 6 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc05 | Support with bathing | 2 (0.7%) | 12 (4.1%) | 148 (51.0%) | 85 (29.3%) | 36 (12.4%) | 5 (1.7%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| mc06 | Skin care | 3 (1.0%) | 8 (2.8%) | 127 (43.8%) | 109 (37.6%) | 32 (11.0%) | 9 (3.1%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| mc07 | Wound care | 4 (1.4%) | 17 (5.9%) | 203 (70.0%) | 53 (18.3%) | 11 (3.8%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc08 | IV/central line site care and assessments according to hospital policy | 2 (0.7%) | 5 (1.7%) | 186 (64.1%) | 68 (23.4%) | 21 (7.2%) | 6 (2.1%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| mc09 | Mouth and/or dental care | 5 (1.7%) | 18 (6.2%) | 89 (30.7%) | 99 (34.1%) | 59 (20.3%) | 19 (6.6%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| mc10 | Assist with toileting needs within 5 min of request | 5 (1.7%) | 20 (6.9%) | 141 (48.6%) | 89 (30.7%) | 26 (9.0%) | 8 (2.8%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| mc11 | Vital signs assessed as ordered | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 223 (76.9%) | 50 (17.2%) | 14 (4.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc12 | Monitoring intake/output | 3 (1.0%) | 12 (4.1%) | 194 (66.9%) | 52 (17.9%) | 26 (9.0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc13 | Glucose monitoring as ordered | 3 (1.0%) | 14 (4.8%) | 209 (72.1%) | 51 (17.6%) | 12 (4.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc14 | Medications administered within 30 min before or after scheduled time | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 180 (62.1%) | 84 (29.0%) | 20 (6.9%) | 4 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc15 | PRN medication requests acted on within 15 min of needs assessment | 2 (0.7%) | 3 (1.0%) | 197 (67.9%) | 74 (25.5%) | 11 (3.8%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc16 | Assess effectiveness of PRN medications | 2 (0.7%) | 4 (1.4%) | 81 (27.9%) | 115 (39.7%) | 60 (20.7%) | 24 (8.3%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| mc17 | Leading conversations with patients and/or family concerning implementation of care processes (e.g. nursing assessment) | 3 (1.0%) | 8 (2.8%) | 50 (17.2%) | 83 (28.6%) | 99 (34.1%) | 37 (12.8%) | 10 (3.4%) |

| mc18 | Focused assessments according to patient condition (e.g. assessment of pain or delirium) | 3 (1.0%) | 10 (3.4%) | 68 (23.4%) | 99 (34.1%) | 85 (29.3%) | 21 (7.2%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| mc19 | Patient and/or family teaching about illness, tests, and therapy | 2 (0.7%) | 8 (2.8%) | 91 (31.4%) | 130 (44.8%) | 46 (15.9%) | 10 (3.4%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| mc20 | Preparation with patient and/or family for discharge | 7 (2.4%) | 34 (11.7%) | 116 (40.0%) | 84 (29.0%) | 44 (15.2%) | 4 (1.4%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| mc21 | Teaching and training of patients and/or family (e.g. insulin injection) | 9 (3.1%) | 77 (26.6%) | 78 (26.9%) | 68 (23.4%) | 48 (16.6%) | 7 (2.4%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| mc22 | Emotional support to patient and/or family | 3 (1.0%) | 10 (3.4%) | 96 (33.1%) | 108 (37.2%) | 66 (22.8%) | 6 (2.1%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| mc23 | Full documentation of all necessary data | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 101 (34.8%) | 117 (40.3%) | 55 (19.0%) | 13 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| mc24 | Response to call light is initiated within 5 min of request | 4 (1.4%) | 8 (2.8%) | 163 (56.2%) | 82 (28.3%) | 23 (7.9%) | 9 (3.1%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| mc25 | Participation in doctors rounds | 3 (1.0%) | 7 (2.4%) | 192 (66.2%) | 60 (20.7%) | 26 (9.0%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Free-text responses of forty-three participants were received for the MISSCARE. About half of these related to the comprehensibility of the questionnaire. Five of those described that ‘The questionnaire is clearly understandable’. Three participants stated that the formulations were long or complicated. Concerning the question, it was not clear to all participants that they were asked about the last seven working days: “Could not give details (…) because I have not worked for the last 7 days”. Concerning the items, seven participants reported that not all of them were relevant in their setting: “I work in a neonatological unit, so some questions could not be answered”. Concerning the response scale, there were two feedbacks pointing out that the distinction between the response options was not defined clearly enough and one person stated that the response option ‘always performed’ would have been useful. There were two answers regarding the questionnaire's applicability that suggested clarity and ease of use.

The exploratory factor analysis (EFA)’s sampling adequacy was marvellous (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO): 0.91). The EFA scree plot indicated that a single-factor solution would explain 33.2% of the variance. While factor loadings are ideally above 0.5, three items loaded below 0.4 (Table 3). Internal consistency was relatively high (Cronbach's alpha: 0.917).

| Item no. | Item of the German MISSCARE | Factor 1 |

|---|---|---|

| mc18 | Focused assessments according to patient condition (e.g. assessment of pain or delirium) | 0.704 |

| mc16 | Assess effectiveness of PRN medications | 0.676 |

| mc09 | Mouth and/or dental care | 0.671 |

| mc06 | Skin care | 0.662 |

| mc23 | Full documentation of all necessary data | 0.656 |

| mc17 | Leading conversations with patients and/or family concerning implementation of care processes (e.g. nursing assessment) | 0.649 |

| mc19 | Patient and/or family teaching about illness, tests, and therapy | 0.618 |

| mc01 | Ambulation as planed or ordered | 0.597 |

| mc24 | Response to call light is initiated within 5 min of request | 0.587 |

| mc22 | Emotional support to patient and/or family | 0.586 |

| mc02 | Turning patient as planed or ordered | 0.578 |

| mc05 | Support with bathing | 0.573 |

| mc15 | PRN medication requests acted on within 15 min of needs assessment | 0.550 |

| mc14 | Medications administered within 30 min before or after scheduled time | 0.547 |

| mc10 | Assist with toileting needs within 5 min of request | 0.541 |

| mc20 | Preparation with patient and/or family for discharge | 0.529 |

| mc12 | Monitoring intake/output | 0.494 |

| mc21 | Teaching and training of patients and/or family (e.g. insulin injection) | 0.476 |

| mc08 | IV/central line site care and assessments according to hospital policy | 0.469 |

| mc03 | Feeding patient when the food is still warm | 0.447 |

| mc04 | Setting up meals for patient who feeds themselves | 0.430 |

| mc11 | Vital signs assessed as ordered | 0.424 |

| mc07 | Wound care | 0.393 |

| mc13 | Glucose monitoring as ordered | 0.381 |

| mc25 | Participation in doctors rounds | 0.362 |

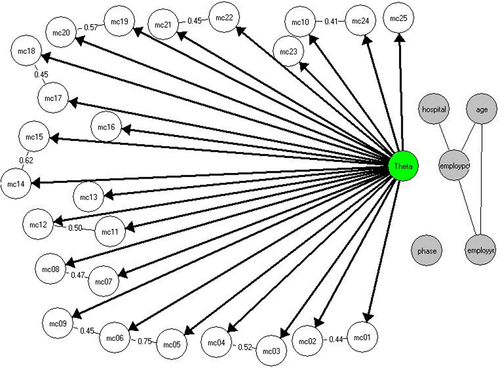

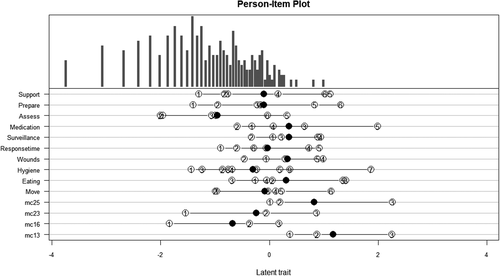

For the Rasch analysis, response categories 1 – 5 have been transformed first to 0–4, and then, the categories with the values 3 and 4 have been combined. As several item pairs showed LDs, a fit of items to the Rasch model was rejected. However, a GLLRM fit succeeded. The conditional likelihood ratio (CLR) test for homogeneity was not significant (p = .623), and inter-subsample item parameter estimates differed only randomly, indicating the absence of DIF. Furthermore, it showed significant LDs in eleven item pairs—mainly because they related to common topics. Figure 1 presents the item response theory (IRT) graph of the GLLRM. A targeting assessment indicated an individual mean of −1.23, where 0.05 would be optimal; that is, participants answered that the nursing activities have been performed for a disproportionately large number of items. As a result, the sum score distribution is right-skewed (Figure 2). The reliability of the measures is relatively high (0.9).

5.2 The BERNCA-R

In Phase 1 and Phase 2, 169 (32.8%) and 119 (23.1%) respondents, respectively, completed the BERNCA-R, resulting in 288 response sets (total response rate: 28.0%). Table 1 summarizes respondents’ socio-demographic and professional variables and response rate per hospital.

Of 288 response sets, 263 (91.3%) were complete (missing values: 76 (0.83%); range of missing values/item: 0–6).

Free-text responses of forty-nine participants were received for the BERNCA-R. About two-third of these related to the comprehensibility of the questionnaire. General answers on comprehensibility indicate that the questionnaire is understandable. Concerning the question, it was not clear to three participants that they were asked about the last seven working days: “(…) often work only one day in seven days”. Five others stated that they “(…) consider the period of 7 working days too short”. Concerning the items, eleven participants reported that not all of them were relevant in their setting: “Not all items are relevant to the ICU”. Concerning the response scale, there was no reply. Feedback on applicability was mixed: three respondents considered the questionnaire straightforward; three others had difficulty logging in and completing it.

The EFA’s sampling adequacy was marvellous (KMO = 0.93); the scree plot indicated that a single factor explained 36.3% of variance. However, five loadings were below 0.4, including two below 0.3, with residual correlations remaining high. The internal consistency was relatively high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.94). Two- to five-factor models did not yield a simple structure with clearly defined factors. In a further attempt, after we deleted six items that appeared to fit poorly conceptually, a factor analysis showed a one-factor solution with reasonably high loadings but still high residual correlations.

Neither a Rasch model nor a GLLRM achieved an adequate fit for the remaining items. In addition to LDs between many item pairs, there was DIF regarding age; that is, despite equal levels of perceived missed nursing care, different age groups responded differently to individual items. Recognizing that the BERNCA-R could not be Rasch-scaled, we discontinued the analysis.

5.3 Construct validity

We assessed construct validity by having eight clinical nurse specialists’ estimate missed nursing care for 13 units prior to data collection. Due to the described difficulties with the BERNCA-R, we continued the evaluation only with the MISSCARE. Four units with less than five responses were excluded. By presenting those estimations alongside the mean sum score per unit, Table 4 shows that the experts’ estimates and the mean sum scores per unit have the same tendency and that assumed differences between units are reflected in the figures.

| Department; Unit (n) | Estimation of the clinical nurse specialists before data collectiona | Mean sum score MISSCAREb |

|---|---|---|

| Department 1; Unit A (7) | Nearly always performed | 28.57 |

| Department 1; Unit B (14) | Nearly always performed | 33.07 |

| Department 2; Unit A (8) | Partly performed, partly missed; similar to Department 2, Unit B | 49.25 |

| Department 2; Unit B (9) | Partly performed, partly missed; similar to Department 2, Unit A | 43.56 |

| Department 3; Unit A (9) | Frequently performed | 51.33 |

| Department 4; Unit A (5) | Frequently performed | 36.00 |

| Department 4; Unit B (5) | Necessary nursing activities were more often missed than on Department 4, Unit A | 62.20 |

| Department 5; Unit A (11) | Frequently performed | 41.18 |

| Department 5; Unit B (6) | Frequently missed | 46.00 |

- a Overall assessment of performed and missed nursing care in their unit (necessary nursing activities nearly always performed, frequently performed, partly performed–partly missed, frequently missed and nearly always missed) or comparison of two units with regard to the extent of missed nursing activities.

- b Added sum scores of participants divided per number of participants per unit.

6 DISCUSSION

Our methodological study is based on the development of a conceptual definition for nursing care activities for the Swiss acute care context. This definition was the foundation for selecting and adapting the MISSCARE in order to operationalize the concept. It also guided our quantitative crossover pilot study to assess the German MISSCARE’s reliability and validity and compare it with the BERNCA-R.

The development of a conceptual definition for our setting was crucial, since no definition for nursing care activities in the context of unfinished nursing care was available. Furthermore, we describe performed and missed nursing care as characteristics of the concept of nursing care activities. Since the two characteristics are relational, it is essential that both are explicitly described. Additionally, our definition is congruent with the estimation of selected nursing care activities on a continuum between performed and missed to operationalize the latent construct. Performed nursing care has so far only been implicitly described or measured, for example by the response option ‘never missed’ in the original MISSCARE (Kalisch & Williams, 2009). However, it remains unclear how the answer ‘never missed’ can be interpreted, since a definition of the overall concept nursing care activities is missing. The conceptual definition was also pivotal for the choice and adaption of the MISSCARE as a measuring instrument. It guided our cultural and structural adaptions to the questionnaire, and the analysis and interpretation of the data.

Our quantitative crossover pilot study then provided preliminary evidence of the German MISSCARE’s reliability and validity regarding measurement of performed and missed nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals. Our Rasch analysis indicated that structural adjustments, including removing, summarizing or reformulating various items, would be useful. In contrast, the BERNCA-R did not prove sufficiently reliable for our context and purposes, which is a first-time finding.

In our pilot study, we observed considerable differences between the MISSCARE and the BERNCA-R. To the best of our knowledge, one earlier study directly compared the PIRNCA with the MISSCARE using a descriptive cross-sectional design; however, it did not explicitly suggest an advantage of either (Jones, Gemeinhardt, Thompson, & Hamilton, 2016). We chose a crossover design because the MISSCARE and BERNCA-R appear very similar, and simultaneous distribution could have led participants who had not carefully read the question to transfer their answers from one questionnaire to the other. We assumed that a washout period of four weeks would be sufficient to avoid biasing responses on the second questionnaire. Although the study design was complicated, it proved methodologically effective: data analysis clearly shows the differences between the two questionnaires. We interpret these with the different conceptual backgrounds and developments of the two measuring instruments.

Few values were missed per item on either questionnaire—fewer than reported elsewhere (Bragadóttir, Kalisch, Smáradóttir, & Jónsdóttir, 2015; Dabney, Kalisch, & Clark, 2019; Sist et al., 2017)—and the generally positive tone of the qualitative feedback concerning the German MISSCARE’s clarity and ease of use indicates high applicability. With regard to the comprehensibility of the MISSCARE, there is qualitative indication that specifications or reformulations relating to the question, the response scale and the different settings should be considered. For that questionnaire, face validity was established by an expert panel confirming cultural acceptability, comprehensibility and completeness regarding the latent construct of nursing care activities. Supporting convergent validity, the overall pattern of clinical nurse specialists’ estimates prior to data collection echoed the tendency of the mean sum scores per unit, and supporting discriminant validity, the estimated differences between the units were reflected in the figures.

Our exploratory factor analysis showed that the German MISSCARE is a single-factor measurement instrument that captures the latent construct of nursing care activities. However, as three items loaded below 0.4, these must be reconsidered during further adaption. We based our choice of a reflective measurement model for this questionnaire on the conceptual background of missed nursing care (Kalisch et al., 2009), our working definition and three assumptions: first, that the latent construct nursing care activities exist independently of the measures used; second, that variances within that construct cause variation between item measures; and third, that, as all items are indicators of nursing care activities, adding or leaving any out does not change the latent construct (Coltman, Devinney, Midgley, & Venaik, 2008). This indicates a reflective measurement model, and in that case, the EFA and Rasch modelling are appropriate analytical methods. And as our scale proved unidimensional, the calculation of a sum score is adequate (Coltman et al., 2008; Streiner, 2003). However, other research groups consider the MISSCARE as a list of nursing activities, not necessarily related to one another and form nevertheless a composite mean score (Dabney et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2015; Kalisch & Williams, 2009). Yet, few describe their calculation processes in detail; therefore, we calculated only sum scores.

For the MISSCARE data, using a GLLRM provided important information on how to refine the translated questionnaire. For example, 11 sets of items showed high locally dependence. It is apparent that they focus on common topics. Since items with high LD do not add value in terms of capturing the latent construct of interest, they should be adapted. Possible adaptions would include removing, summarizing or reformulating items. Furthermore, the GLLRM revealed poor targeting, leading to overloading of most items. That is, a disproportionately small number of participants indicated missing the targeted activities. It may be possible to adapt the overloaded items to achieve a more balanced questionnaire in terms of its sensitivity to missed care. To our knowledge, only one other publication has analysed the MISSCARE—with four response categories—via a Rasch analysis. Unlike us, that publication's authors identified DIFs concerning respondent gender and whether their hospital was metropolitan or rural (Blackman et al., 2015).

For the BERNCA-R, the reflective measurement model could not be confirmed. In addition, while a single-factor solution was previously assumed for it, it has been shown to be multidimensional (Gurková et al., 2019; Schubert et al., 2007; Uchmanowicz et al., 2019; Zúñiga et al., 2016); furthermore, researchers using a Slovak version of the PIRNCA were recently unable to find an optimal factor structure and questioned its validity (Gurková et al., 2019). Although the German BERNCA-R has been used repeatedly, this is the first study reporting about its psychometric properties. In terms of content, a multifactor solution can be attributed partly to the questionnaire's development process and partly to its multiple levels of content (Schubert et al., 2007). Considering this and other noted issues concerning the questionnaires and their measures, we chose neither to use the BERNCA-R to measure performed and missed nursing care nor to continue with inter- or intra-instrument comparisons.

As our pilot study results for the German MISSCARE support its validity, reliability and applicability, we chose to use it for the third data collection phase of the multicentre research programme. To our knowledge, this will be the first time the MISSCARE has been used for continuous monitoring of nursing service context factors in acute care hospitals.

6.1 Implications for nursing management and research

This methodological study is part of the continuous monitoring of nursing service context factors in a sample of Swiss acute care hospitals. Its findings will broaden the knowledge base concerning performed and missed nursing care and its measurability in the Swiss–German context. The German MISSCARE allows longitudinal monitoring of performed and missed nursing care—for which Swiss data are currently scant—and benchmarking of participating hospitals and units. Furthermore, relationships among nursing service context factors, performed and missed nursing care, and nurse-sensitive patient and nursing outcomes can be observed, explored and monitored. Our findings will help the participating hospitals’ nursing managers make timely evidence-based decisions regarding resource allocation, interventions, evaluation and overall patient care, for example staffing (Kontio et al., 2013). However, it is important to bear in mind that these results reflect only the frequency of performed and missed nursing care, not the quality or adequacy of performed activities.

Regarding implications for future research, our results regarding the German MISSCARE will guide structural adjustments of the instrument. Then, after adaption of the questionnaire, another data collection and psychometric analysis are indicated. Our working definition has proved to be valuable. It is however reasonable to refine and specify this theory-based definition with qualitative follow-up studies. Regarding the BERNCA-R, our results indicate that it should be revised.

6.2 Limitations

At least three notable limitations apply to this methodological study; first, as the studied concept and its operationalization are highly context-dependent, comparisons can only be made conditionally (Zeleníková et al., 2019); second, purposive sampling and voluntary participation may have led to selection bias; that is, only persons particularly interested in the studied phenomenon may have participated. In combination with the complex design, this could partly explain the low response rate and the results may not reflect the experience of non-participants (Vincelette, Thivierge-Southidara, & Rochefort, 2019); and third, we relied on self-reporting, which is prone to recall bias and social desirability.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This methodological study underlines the relevance of a conceptual definition before operationalizing and interpreting the phenomenon of nursing care activities. We yielded preliminary evidence that the German MISSCARE is valid and reliable to measure performed and missed nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals. It also indicated that the questionnaire would benefit from structural adjustments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all participating nurses and midwifes, as well as the nursing managers and the steering committee of the monitoring programme. Furthermore, we thank the clinical nurse specialists, translators and the editor for their contribution. The primary author is a PhD student, and she would like to sincerely thank her supervisors for their continued helpful support and guidance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CH, MM, RS and MKD developed the design of the study. CH, MM and MKD were involved in the collection and management of the data. MM analysed the statistical data, CH performed the qualitative data analysis. CH, MM, RS and MKD interpreted the results. CH drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the article. CH works in this research programme as a PhD student focussing on “missed nursing care” at the University of Witten/Herdecke, Germany. RS and MKD are CH's PhD advisors. RS is the sponsor and MKD the scientific and project leader of this research programme. MM is the leading statistician.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study followed the principals of good clinical practice and was approved by the governmental ethics committees (BASEC Nr. Req-2019–00392). Participation was voluntary, informed consent obtained and confidentiality assured.